Abstract

Intraventricular rupture of craniopharyngioma cysts is an unusual event which is associated with a high risk of loculated or communicating hydrocephalus. A 75-year-old woman presented at the Emergency Department of our hospital with mental status deterioration due to chemical ventriculitis and acute hydrocephalus following the intraventricular rupture of a craniopharyngioma cyst. The patient was treated with stress-dose steroid therapy. In addition, she underwent placement of an external ventricular drain and endoscopy-assisted intra-cystic placement of an Ommaya reservoir for the aspiration of the cystic fluid. The patient's condition improved; she was shunted in an expeditious fashion and discharged from the Intensive Care Unit within 2 weeks of her admission with the reservoir in place for the continued drainage of the cyst.

Key Words: Craniopharyngioma, cyst, hydrocephalus, intraventricular, rupture, supracellar, ventriculitis

INTRODUCTION

Craniopharyngioma cysts are pathological entities well described in literature. Nearly 16 cases of ruptured craniopharyngioma cysts have been reported so far.[1,2,3,4,5] Most commonly, craniopharyngioma cysts rupture into the subarachnoid space or the sphenoid sinus and are draining into the nasopharynx.[2] Intraventricular cystic lesions have been described in the literature, as a finding more commonly observed in older population.[6] The patients present at the Emergency Department (ED) with a variety of symptoms including headache, aphasia, lethargy, meningismus, fever, rhinorrhea as well as loss of vision acuity.[1,2,7,8] In addition, cyst rupture has been correlated to cerebral vasospasm and ischemia.[7]

The pluralism of clinical manifestations of this rare pathological entity makes the differential diagnosis and treatment strategy a puzzling problem for the emergency care physicians. Our aim is to present an uncommon case of spontaneous intraventricular rupture of a craniopharyngioma cyst in an elderly patient that was treated successfully with steroids, ventriculo-peritoneal shunting, and the intracystic placement of an Ommaya reservoir.

CASE REPORT

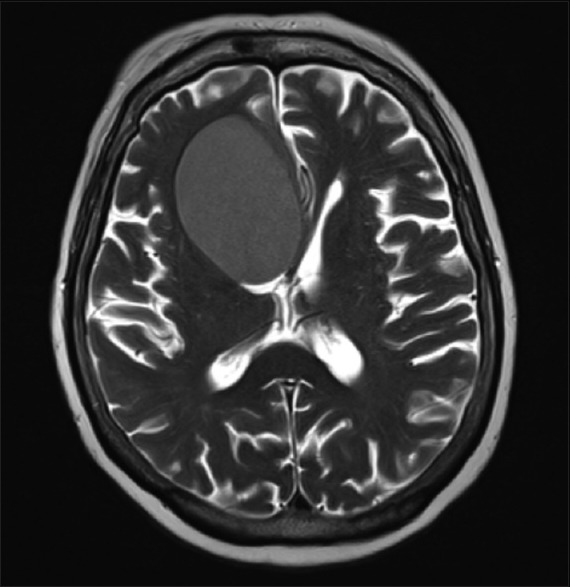

A 75-year-old woman with a known intracranial mass referred to our outpatient clinic. The lesion was incidentally discovered after a head computed tomography (CT) scan that she had in the past for the evaluation of a confusion episode secondary to hypoglycemia (diabetes mellitus being the only comorbidity in this patient). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of her brain revealed a cystic sellar mass with mass effect on the right lateral ventricle [Figure 1]. The patient had ophthalmologic and endocrinologic evaluations that demonstrated a left temporal, a right superior temporal visual field deficit, and panhypopituitarism. Based on these imaging and clinical findings, the diagnosis of a craniopharyngioma was made. She was then placed on steroid therapy as well as hormone replacement therapy, and surgical resection was planned. In the interim, she began developing severe lower extremity weakness that delayed surgery. A diagnosis of steroid-induced myopathy was made.

Figure 1.

T2-weighted axial magnetic resonance image of the brain demonstrating prominent, hypointense, right cystic craniopharyngioma with mass effect on the right lateral ventricle

Immediately after the evaluation of her lower extremity weakness, the patient presented to the ED with an acute onset of altered mental status. Her Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score on initial presentation was 10. Noncontrast head CT imaging demonstrated changes in the density of the cyst and the density of the ventricular cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) [Figure 2]. Subsequent MRI of the brain was strongly suggestive of intraventricular rupture of the cyst [Figure 3]. Intraventricular cyst rupture was confirmed by a lumbar puncture that demonstrated marked pleocytosis with elevated levels of cholesterol and lactate dehydrogenase identified by CSF analysis. Given these findings, a diagnosis of chemical ventriculitis was made.

Figure 2.

Noncontrast axial computed tomographic image of the head. The hypodensity in the nondependent part of the cyst suggests intermixing of cyst content with cerebrospinal fluid

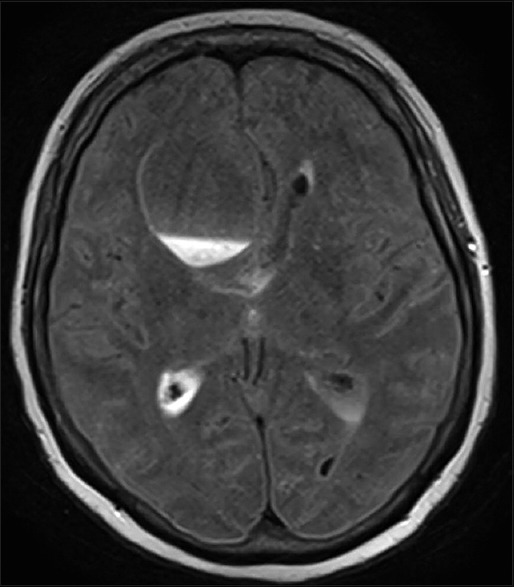

Figure 3.

Fluid-attenuated inversion recovery-weighted axial magnetic resonance image of the brain demonstrating fluid signal within the cystic cavity without change in cyst size and persistent ventricular dilatation, representing a change from the initial imaging findings

The patient was initially started on high-dose steroid therapy with significant improvement of her level of consciousness (GCS: 13/15). Once her clinical condition was medically optimized, the patient was taken to the operating room for endoscopic-assisted intracystic placement of an Ommaya reservoir [Figure 4]. Cytopathologic analysis of the aspirate revealed proteinaceous material, blood, and histiocytes, some with hemosiderin. She underwent shunt placement for continued ventriculomegaly 5 days after Ommaya reservoir placement. Her condition improved, and she was discharged from the Intensive Care Unit within 2 weeks from her admission.

Figure 4.

Noncontrast axial computed tomographic scan of the head showing placement of the Ommaya reservoir in the cystic cavity

DISCUSSION

In the literature, it is postulated that the formation of craniopharyngioma cysts is correlated to inflammation processes.[9] Spontaneous rupture of cystic craniopharyngiomas was documented initially in the second decade of the 19th century.[10] Symptomatology includes loss of vision acuity, headache, meningismus, hyperemesis, and neurological decline, which are strong indications of increased intracranial pressure. Obesity and hypopituitarism are often observed in these patients in addition to diabetes insipidus.[11]

An emergency imaging study of the brain should be provided in every case. A head CT/MRI scan can show the cystic mass as well as the existence of hydrocephalus which is a result of the high cholesterol levels. Differential diagnosis based on imaging findings includes dermoid cysts, epidermoid cysts, Rathke cleft cysts, teratomas, schwannomas, craniopharyngiomas, and gliomas.[12] The laboratory examinations should include the endocrinologic profile of the patient. Steroids should be provided immediately after the verification of lesion's location and nature.

CSF analysis can also show abnormalities in the levels of lactate dehydrogenase and cholesterol.[4] Satoh et al.[10] presented a series of five cases of ruptured craniopharyngioma cysts and their radiological features. Three of five of these cases also showed CSF changes, and only one of these cases was diagnosed as a cystic rupture into the cistern, based solely on CSF analysis.

To date, only two cases of spontaneous intraventricular rupture of a craniopharyngioma cyst have been described.[5,13] Ravindran et al.[5] reported a case of a 12-year-old boy who had intermittent symptoms of high intracranial pressure. The patient underwent resection of the cyst and died on postoperative day 19. Kulkarni et al.[13] described a case of a 38-year-old woman who had an acute change in the level of consciousness and symptomatology compatible with acute ventriculitis. She was treated with ventricular drainage and steroid therapy.

At last, the treatment algorithm for ruptured craniopharyngioma cysts consists of ventricular drainage and steroid therapy.[5,10,13] In children and in patients who are not medically stable to undergo a large craniotomy for resection of the ruptured cystic component, the placement of an Ommaya reservoir constitutes an alternative solution.[14,15] The placement of an Ommaya reservoir can serve as a mean for repeated drainage of the cyst cavity and the ventricles (if these structures are in free communication) which can be used outside of the intensive care setting as well as at a rehabilitation facility.

CONCLUSION

Intraventricular rupture of craniopharyngioma cysts is an exceedingly rare occurrence. The patients present at the ED with a variety of symptoms which indicate increased intracranial pressure. Physicians should seek at patient's medical history for any comorbidity that could indicate the presence of a cellar mass such as hormone deficiencies, visual loss, and chronic obesity. An emergency CT scan and/or MRI scan of the head should be conducted to clarify the source of the clinical findings. The endocrinologic profile of the patient is also significant for the diagnosis. Administration of stress-dose steroid therapy should be the next step before the final surgical management.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge Michael Miller, MD, Neuroradiologist, Paul H. Dressel, BFA, for preparation of the illustrations, and Debra J. Zimmer for editorial support (all at University at Buffalo Neurosurgery).

REFERENCES

- 1.Krueger DW, Larson EB. Recurrent fever of unknown origin, coma, and meningismus due to a leaking craniopharyngioma. Am J Med. 1988;84(3 Pt 1):543–5. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(88)90281-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maier HC. Craniopharyngioma with erosion and drainage into the nasopharynx. An autobiographical case report. J Neurosurg. 1985;62:132–4. doi: 10.3171/jns.1985.62.1.0132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Okamoto H, Harada K, Uozumi T, Goishi J. Spontaneous rupture of a craniopharyngioma cyst. Surg Neurol. 1985;24:507–10. doi: 10.1016/0090-3019(85)90265-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patrick BS, Smith RR, Bailey TO. Aseptic meningitis due to spontaneous rupture of craniopharyngioma cyst. Case report. J Neurosurg. 1974;41:387–90. doi: 10.3171/jns.1974.41.3.0387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ravindran M, Radhakrishnan VV, Rao VR. Communicating cystic craniopharyngioma. Surg Neurol. 1980;14:230–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Behari S, Banerji D, Mishra A, Sharma S, Sharma S, Chhabra DK, et al. Intrinsic third ventricular craniopharyngiomas: Report on six cases and a review of the literature. Surg Neurol. 2003;60:245–52. doi: 10.1016/s0090-3019(03)00132-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shida N, Nakasato N, Mizoi K, Kanaki M, Yoshimoto T. Symptomatic vessel narrowing caused by spontaneous rupture of craniopharyngioma cyst – Case report. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 1998;38:666–8. doi: 10.2176/nmc.38.666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Takahashi T, Kudo K, Ito S, Suzuki S. Spontaneously ruptured craniopharyngioma cyst without meningitic symptoms – Two case reports. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 2003;43:150–2. doi: 10.2176/nmc.43.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pettorini BL, Inzitari R, Massimi L, Tamburrini G, Caldarelli M, Fanali C, et al. The role of inflammation in the genesis of the cystic component of craniopharyngiomas. Childs Nerv Syst. 2010;26:1779–84. doi: 10.1007/s00381-010-1245-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Satoh H, Uozumi T, Arita K, Kurisu K, Hotta T, Kiya K, et al. Spontaneous rupture of craniopharyngioma cysts. A report of five cases and review of the literature. Surg Neurol. 1993;40:414–9. doi: 10.1016/0090-3019(93)90223-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zada G, Lin N, Ojerholm E, Ramkissoon S, Laws ER. Craniopharyngioma and other cystic epithelial lesions of the sellar region: A review of clinical, imaging, and histopathological relationships. Neurosurg Focus. 2010;28:E4. doi: 10.3171/2010.2.FOCUS09318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ren X, Lin S, Wang Z, Luo L, Jiang Z, Sui D, et al. Clinical, radiological, and pathological features of 24 atypical intracranial epidermoid cysts. J Neurosurg. 2012;116:611–21. doi: 10.3171/2011.10.JNS111462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kulkarni V, Daniel RT, Pranatartiharan R. Spontaneous intraventricular rupture of craniopharyngioma cyst. Surg Neurol. 2000;54:249–53. doi: 10.1016/s0090-3019(00)00288-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shukla D. Transcortical Transventricular Endoscopic Approach and Ommaya Reservoir Placement for Cystic Craniopharyngioma. Pediatr Neurosurg. 2015;50:291–4. doi: 10.1159/000433605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moussa AH, Kerasha AA, Mahmoud ME. Surprising outcome of ommaya reservoir in treating cystic craniopharyngioma: A retrospective study. Br J Neurosurg. 2013;27:370–3. doi: 10.3109/02688697.2012.741732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]