Abstract

Post traumatic stress disorder is a psychiatric disease that is usually precipitated by life threatening stressors. Myocardial infarction, especially in the young can count as one such event. The development of post traumatic stress after a coronary event not only adversely effects psychiatric health, but leads to increased cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. There is increasing evidence that like major depression, post traumatic stress disorder is also a strong coronary risk factor. Early diagnosis and treatment of this disease in patients with acute manifestations of coronary artery disease can improve patient outcomes.

Key Words: Postcoronary artery bypass graft surgery posttraumatic stress disorder, postmyocardial infarction and posttraumatic stress disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder

INTRODUCTION

Cardiac disease is the leading cause of death in the United States.[1] Acute coronary syndromes (ACSs) constitute a vast majority of former. Annually, approximately 735,000 Americans experience a myocardial infarction (MI).[2] As mortality from coronary events has been decreasing with advancements in medical science, we are now seeing more chronic sequelae/morbidity related to coronary heart disease (CHD). Psychiatric diseases significantly contribute toward the latter. It is well known that medical diseases can precipitate posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).[3] MI can be one such traumatic event. Post-MI (PMI) major depression, acute stress disorder, and PTSD are well described in the literature. Although the data on negative cardiovascular (CV) effect of major depression following MI is more robust,[4,5] there is increasing evidence (albeit, primarily observational) of an adverse CV risk associated with PTSD patients after an MI.

DEFINITION OF POSTTRAUMATIC STRESS DISORDER

The 5th edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Diseases (DSM) puts forth specific criteria for the diagnosis of PTSD under the classification of Trauma and Stressor-related disorders. Criteria A: The person was exposed to: death, threatened death, actual or threatened serious injury, or actual or threatened sexual violence. Criteria B: Patient re-experiences the traumatic events in the form of flashbacks, intrusions, nightmares resulting in avoidance of stimuli which may have been associated with the initial trauma (Criteria C). Criteria D: The presence of negative thoughts or feelings that began or worsened after the trauma, for example, inability to recall key features of the trauma or overly negative thoughts and assumptions about oneself or the world. Criteria E: The presence of 2 trauma-related arousal and reactivity that began or worsened after the trauma, such as irritability or aggression, risky or destructive behavior, hypervigilance, increased startle, and poor concentration. All these defining criteria (A-E) have to be present and must last for more than 1 month (Criteria F). These should also significantly interfere with normal day-to-day functioning of the patient (Criteria G).[6,7] Studies have described PTSD either through self-describing questionaries' or through posttraumatic diagnostic scales.

POSTTRAUMATIC STRESS DISORDER AND THE HEART

In the last few decades, once large prospective studies established hypertension, smoking, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, etc., as the traditional cardiac risk factors,[8] the focus shifted to psychosocial stressors. Subsequently, the INTER-HEART research group and other researchers established that psychosomatic and mental diseases conferred cardiac risk.[9,10,11] On the other hand, MI often has an acute and frequently unexpected presentation, and thus it has the potential to cause psychological trauma. This along with growing evidence that medical diseases like MI can be the inciting traumatic event for patients with PTSD has led researchers to describe a specific PMI posttraumatic diagnostic scale.[12]

PREVALENCE OF POSTMYOCARDIAL INFARCTION-POSTTRAUMATIC STRESS DISORDER

There has been controversy regarding true prevalence of PTSD following an MI, primarily because studies utilizing self-reported questionnaires resulted in an inflated prevalence of the disease. In contrast, when utilizing more strict structured interviews with specific diagnostic scales, the prevalence is lower.[13] Nonetheless, most researchers agree that in general PMI-PTSD is under-diagnosed, as patients often may not want to answer questions.[7] Studies have reported the prevalence of PMI-PTSD to be as high as 30%, but a meta-analysis of 24 observational cross-sectional studies estimated the prevalence to be 12%.[14,15] This is much higher than the prevalence of PTSD in the general population (10%–12% in men and 5%–6% in women).[16] As survival rates from MI and cardiac arrest (CA) have increased with advanced medical technology both in the community (e.g., automated external defibrillator) and in-hospital, more people are living to remember these life-threatening events. As a result, the relationship between cardiac events and subsequent traumatic symptoms is also coming into light. These patients may be prone to develop re-experiencing (e.g., recalling the cardiac event or defibrillator shocks, dreams of CA, flashbacks of medical interventions, and surgical procedures), avoidance (e.g., avoid reminders of the cardiac event such as the location of the event, the hospital, medication, situations in which heart rate increases such as exercise or sexual activity), and arousal symptoms (e.g., preoccupation with heart rate or chest pain; insomnia).[17] There is some controversy about the chronicity of PMI-PTSD. The study by Pedersen et al. suggested that its prevalence decreases over time,[18] but Abbas and colleagues demonstrated that although the severity decreases, PMI-PTSD follows a more waxing and waning course. If there is long-term follow-up of patients, PMI-PTSD persists in up to two-third of the patients. This has led to advocacy for a longer follow-up of patients. Out of all the clinical features of PTSD, hyperarousability is the least likely to resolve over time.[19]

ETIOLOGY OF POSTMYOCARDIAL INFARCTION-POSTTRAUMATIC STRESS DISORDER

As a majority of patients did not develop PTSD after an MI, research began into personality traits and into stress and coping mechanisms to explain the development of PTSD.[20] Investigation into these areas showed a relationship between PMI-PTSD and neuroticism, Type D personality disorder (defined as being worried, irritable and expressing negative emotions) and alexithymia.[21,22,23] The latter is a subconscious inability to discern and understand emotions. Neurotic traits tended to magnify the impact of MI.[24] Threat to life, feeling intense fear/helplessness, co-existing severe depression, and history of referral to psychotherapist/psychiatrist have been shown to predict more intense symptoms of PMI-PTSD. Several risk factors have been described for the development of PMI-PTSD. These include younger age, lack of social support, severity and duration of chest pain at index admission, and ethnicity of the patients.[18,21,25,26,27] The reason younger people tend to have more PMI-PTSD is that MI is less expected in these younger individuals and so they are less prepared for it.[24,28] As African Americans tend to have MI at a younger age, they tend to have higher PMI-PTSD.[14] In addition, it has been shown that the female gender is not only associated with development of PMI–PTSD, but also is associated with persistence over time.[13,27] Although expected, it was found that PTSD does not correlate with clinical severity of the MI. There is some anecdotal evidence that the subjective perception of the trauma is more important than the severity (number of coronary occlusions, creatinine kinase levels, ejection fraction, etc.) of the trauma itself.[14,25,26,27,29,30,31] Some researchers divided risk of PMI-PTSD into pre-MI, peri-MI, and PMI risk factor categories. Substance abuse was identified as an important pre-MI risk factor, while symptoms of dissociation and poor access to social support were important peri-MI risk determinants of PTSD.[13] Crowded emergency room setting with less than optimal initial care during index MI has been suggested as another factor that might lead to PMI-PTSD.[32]

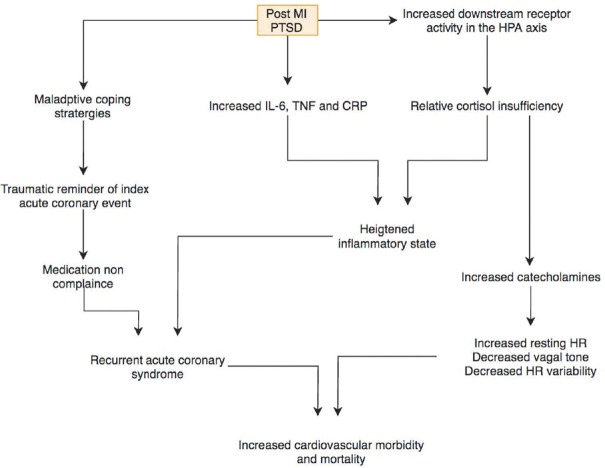

POSTTRAUMATIC STRESS DISORDER AND ADVERSE CARDIOVASCULAR RISK

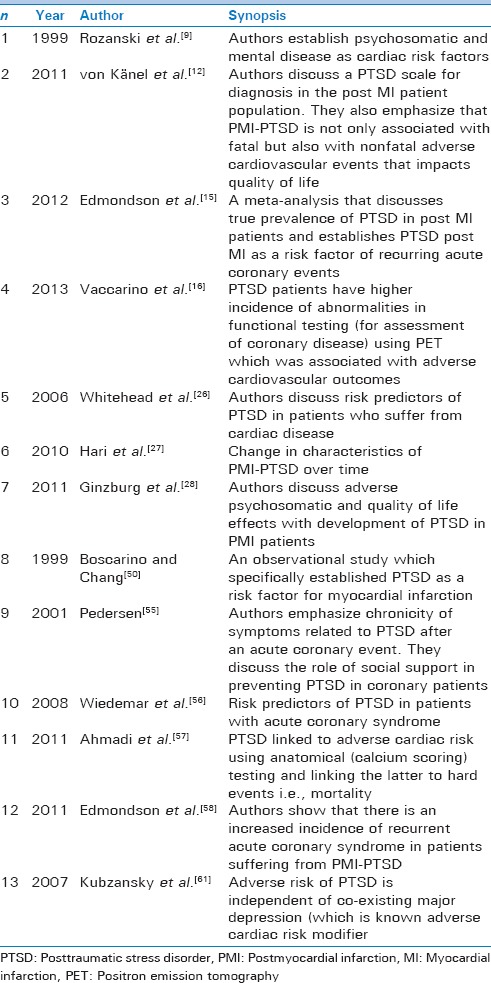

PTSD is a state of adrenergic overactivity. This is secondary to the central effects of stressors on the hypothalamic-pituitary-axis (HPA). This is described as neuro-endocrinal alterations leading to peripheral stress.[33,34] It has been postulated that PTSD causes increased downstream receptor activity, which in turn decreases cortisol levels through negative feedback. Relative cortisol deficiency results in a heightened inflammatory state and an excess of catecholamines, both of which are detrimental to patients with CHD.[35,36,37] These may also cause unfavorable effects such as elevated resting heart rate, heart rate variability, lowered vagal tone, and predisposition to ventricular arrhythmias.[38,39,40,41,42] An interplay between hormonal, psychosomatic, and inflammatory mediators leads to the untoward CV risk in patients with PMI-PTSD [Figure 1]. In addition, Gander and von Känel[7] have demonstrated that patients with PTSD also have increased prevalence of traditional cardiac risk factors such as hypertension, obesity, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, smoking, and low physical activity. PTSD has also been shown to be a pro-coagulant state.[43] Elevated levels of interleukin-6 (IL-6) have been demonstrated in PTSD, which has also been implicated in the progression of atherosclerosis.[44,45] PTSD patients also have elevated levels of other inflammatory markers such as tumor necrosis factor, IL-1, and C-reactive protein all of which carry vascular risk.[46] There is literature supporting increased platelet activity and a shift toward a more atherogenic lipid pool.[47,48,49] Boscarino and Chang established that PTSD increases risk of MI fourfold through cross-sectional studies,[50] but more recent meta-analytical data reveal that the risk may be double in comparison to no PMI-PTSD (odds ratio = 1.7–2.4).[15] This risk is at par with the risk of mortality in PMI-depression.[51] Several observational studies and one recent meta-analysis have shown that PMI PTSD increases CV mortality twofold.[15] The latter also demonstrated that these patients have an elevated risk of recurrent cardiac events. It is postulated that patients with PTSD can have adverse events not only related to adverse pathophysiological cascades but that these patients are more likely to have medication noncompliance. The latter is usually because these medications can serve as traumatic reminders of their index MI (initial trauma) and result in maladaptive coping strategies.[10,52,53] These can also lead to not seeking medical help for a repeat coronary event, accentuating CV morbidity/mortality, and increasing readmissions related to CHD.[54,55] In addition, PMI patients may not develop full-blown PTSD (as diagnosed by strict DSM criteria) but may still have an elevated adverse cardiac risk.[13] There was both an increase in CV mortality and nonfatal CV outcomes (including poor quality of life) associated with PMI-PTSD.[28,56] von Känel et al. demonstrated that for each 10 point increase in PMI-PTSD severity (using a structured PMI-PTSD scales), there was an independent increased risk of nonfatal cardiac events including recurrent MI, coronary stenting, coronary bypass surgery, stroke, and pacemaker insertion. This was the first time that nonfatal CV events were independently linked to PMI-PTSD. In addition, they demonstrated that intrusive symptoms of PTSD were the ones that were specifically associated with CV outcomes.[12] More recently Ahmadi et al. linked objective coronary atherosclerosis and CV mortality to PTSD using coronary calcium scoring (CAC). They demonstrated that PTSD was an independent predictor of CV mortality (independent of the traditional CV risk factors) and additionally each CAC group had higher mortality if they had PTSD compared to if they did not.[57] After anatomical evidence of CHD was linked to PTSD using CAC, another study performed by Vaccarino demonstrated a similar negative relationship between PTSD and CV outcomes using functional testing like positron emission tomography. This study was conducted in Vietnam war veteran twins and also revealed that association between PTSD and CHD was not confounded by familial factors.[16] When specifically looking at the PMI-PTSD population, Edmondson et al. showed that there was a statistically significant increase in major adverse CV events and recurrent ACS during a 42 months' follow-up, independent of the initial Global registry of acute coronary events score or Charlson comorbidity index.[58] This further cements the unfavorable association between PMI-PTSD and future CV disease.[12] Twenty percent patients developed major depression following an MI, thus, there was concern that PTSD PMI seldom occurs as a standalone psychiatric disease.[59] This resulted in concern that at least part of the psychiatric induced untoward cardiac risk PMI may be related to concomitant depression. However, von Känel showed that there is a divergent HPA axis behavior in PTSD in comparison to that in major depression (which can in part help distinguish coexisting depression).[33,60] In addition, Kubzansky et al. demonstrated that the elevated CV risk in PTSD was independent of coexisting major depression and patients with PTSD and depression tended to have higher norepinephrine levels than those with depression alone.[61,62] Given the strong association between MI and development of PTSD with poor CV outcomes, there is a current randomized control trial underway which is trying to evaluate the benefit of short session psychotherapy to prevent PMI-PTSD in patients after an MI.[32] A summary of the most prominent literature available connecting CV disease and PTSD as well as recurrent unfavorable coronary outcomes in patients who develop PMI-PTSD is depicted in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Interplay of psychosomatic, hormonal and inflammatory mediators resulting in adverse cardiovascular events in PMI-PTSD. PTSD-Posttraumatic stress disorder; PMI-postmyocardial infarction; MI-myocardial infarction; HR-Heart rate; HPA-hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal; IL-Interleukin; TNF-Tumor necrosis factor; CRP-C reactive protein

Table 1.

Summary of the predominant literature in relation to diagnostic criteria, risk factors and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with postmyocardial infarction-posttraumatic stress disorder

CORONARY ARTERY BYPASS GRAFT SURGERY-RELATED POSTTRAUMATIC STRESS DISORDER

Cardiac-related PTSD has been reported in 8%–18% of coronary artery bypass graft surgery (CABG) patients between 6 and 12 months postoperatively.[63,64] The said risk may be higher in those with prior experience of undergoing surgery. Stoll et al. compared patients undergoing cardiac surgery with healthy persons and with those undergoing other surgery and noted a higher incidence of PTSD in cardiac surgery patients. Disease severity and duration in Intensive Care Unit were found to be predictors of PTSD.[64] In another study, the strongest risk factor for a higher level of PTSD symptomatology 6 months postoperatively was a higher level of preoperative PTSD symptomatology. Research assessing the relationship between presurgical trauma/PTSD and medical outcomes following CABG is limited.[61,65] Further, most studies have investigated populations receiving elective CABG,[65,66] with few studies including patients undergoing emergency cardiac surgery.[63] Psychosocial factors negatively impact the prognosis of patients with CAD independently of disease severity.[10,67] PTSD may, therefore, increase risk of both psychological and medical adverse outcomes following CABG. PTSD following MI has been shown to predict nonadherence to medication, and increased likelihood of cardiac re-admission and mortality PMI,[68] and it is likely that the same risk applies to post-CABG patients. In post-CABG patients, PTSD symptomatology was significantly associated with impairments in social and emotional functioning, mental health and vitality, and with lower life satisfaction.[64] At 6–12 months postoperatively, it has been associated with impairments in work, social and leisure activities, marital, financial and parental roles, and family relationships.[63] Some investigations have found that degree of PTS symptomatology and not PTSD diagnosis better predicted psychological and medical outcomes.[69] Assessing the scope and severity of PTS symptomatology using the PTS total score may better identify those prone to perceiving the cardiac event and surgery as more frightening and life-threatening than whether the PTS symptoms meet DSM5 diagnostic criteria for current PTSD or not. A lower level of PTSD symptomatology, in relation to being informed of the need for cardiac surgery, was predictive of longer postoperative length of hospital stay, with the finding linked to behavioral mechanisms such as increased use of avoidance coping. A comprehensive preoperative screening of psychological risk for all patients awaiting CABG is a necessary step. The identification of modifiable risk factors for postoperative PTSD can aid in the development of interventions that can reduce the deleterious impact of such problems and improve patient outcomes. Adrenaline is reported to be associated with traumatic memories and PTSD and therefore by corollary B-blockers (BBs) may reduce the incidence of PTSD. BB use on PTSD symptoms has been explored in a limited number of controlled pilot trials, which showed either no effect[70] or only moderate efficacy.[70,71]

CONCLUSION

PTSD has a strong association with MI and CABG and can be a source of considerable morbidity and mortality. Not only can it be precipitated by a MI, but is also detrimental to future CV events. The latter is the result of a combination of pathological coping mechanisms associated with PTSD but also from a swing in the pendulum to a highly pro-atherogenic milieu. Long-term CV mortality and nonfatal adverse cardiac events have been closely tied to PMI-PTSD. Thus, it can be stated that like major depression, PTSD is a strong negative CV risk modifier. A multi-departmental team including a cardiologist, psychiatrist, psychotherapist, and patient's family should closely monitor and manage such patients with PMI-PTSD. Long-term follow-up is strongly recommended as many of these patients develop unfavorable events after a waxing and waning clinical course separated by periods of quiescence.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.National Center for Health Statistics, US. “Health, United States, 2015: With Special Feature on Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities. 2016 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, Arnett DK, Blaha MJ, Cushman M, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2015 update: A report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2015;131:e29–322. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tedstone JE, Tarrier N. Posttraumatic stress disorder following medical illness and treatment. Clin Psychol Rev. 2003;23:409–48. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(03)00031-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shemesh E, Yehuda R, Milo O, Dinur I, Rudnick A, Vered Z, et al. Posttraumatic stress, nonadherence, and adverse outcome in survivors of a myocardial infarction. Psychosom Med. 2004;66:521–6. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000126199.05189.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Watkins LL, Schneiderman N, Blumenthal JA, Sheps DS, Catellier D, Taylor CB, et al. Cognitive and somatic symptoms of depression are associated with medical comorbidity in patients after acute myocardial infarction. Am Heart J. 2003;146:48–54. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8703(03)00083-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Friedman MJ. Finalizing PTSD in DSM-5: Getting here from there and where to go next. J Trauma Stress. 2013;26:548–56. doi: 10.1002/jts.21840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gander ML, von Känel R. Myocardial infarction and post-traumatic stress disorder: Frequency, outcome, and atherosclerotic mechanisms. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2006;13:165–72. doi: 10.1097/01.hjr.0000214606.60995.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wilson PW, D'Agostino RB, Levy D, Belanger AM, Silbershatz H, Kannel WB. Prediction of coronary heart disease using risk factor categories. Circulation. 1998;97:1837–47. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.18.1837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rozanski A, Blumenthal JA, Kaplan J. Impact of psychological factors on the pathogenesis of cardiovascular disease and implications for therapy. Circulation. 1999;99:2192–217. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.16.2192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hemingway H, Marmot M. Evidence based cardiology: Psychosocial factors in the aetiology and prognosis of coronary heart disease. Systematic review of prospective cohort studies. BMJ. 1999;318:1460–7. doi: 10.1136/bmj.318.7196.1460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yusuf S, Hawken S, Ounpuu S, Dans T, Avezum A, Lanas F, et al. Effect of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with myocardial infarction in 52 countries (the INTERHEART study): Case-control study. Lancet. 2004;364:937–52. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17018-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.von Känel R, Hari R, Schmid JP, Wiedemar L, Guler E, Barth J, et al. Non-fatal cardiovascular outcome in patients with posttraumatic stress symptoms caused by myocardial infarction. J Cardiol. 2011;58:61–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jjcc.2011.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roberge MA, Dupuis G, Marchand A. Post-traumatic stress disorder following myocardial infarction: Prevalence and risk factors. Can J Cardiol. 2010;26:e170–5. doi: 10.1016/s0828-282x(10)70386-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rocha LP, Peterson JC, Meyers B, Boutin-Foster C, Charlson ME, Jayasinghe N, et al. Incidence of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) after myocardial infarction (MI) and predictors of ptsd symptoms post-MI – A brief report. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2008;38:297–306. doi: 10.2190/PM.38.3.f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Edmondson D, Richardson S, Falzon L, Davidson KW, Mills MA, Neria Y. Posttraumatic stress disorder prevalence and risk of recurrence in acute coronary syndrome patients: A meta-analytic review. PLoS One. 2012;7:e38915. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vaccarino V, Goldberg J, Rooks C, Shah AJ, Veledar E, Faber TL, et al. Post-traumatic stress disorder and incidence of coronary heart disease: A twin study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62:970–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.04.085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tulloch H, Greenman PS, Tassé V. Post-traumatic stress disorder among cardiac patients: Prevalence, risk factors, and considerations for assessment and treatment. Behav Sci (Basel) 2014;5:27–40. doi: 10.3390/bs5010027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pedersen SS, van Domburg RT, Larsen ML. The effect of low social support on short-term prognosis in patients following a first myocardial infarction. Scand J Psychol. 2004;45:313–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9450.2004.00410.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abbas CC, Schmid JP, Guler E, Wiedemar L, Begré S, Saner H, et al. Trajectory of posttraumatic stress disorder caused by myocardial infarction: A two-year follow-up study. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2009;39:359–76. doi: 10.2190/PM.39.4.b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chung MC, Berger Z, Rudd H. Comorbidity and personality traits in patients with different levels of posttraumatic stress disorder following myocardial infarction. Psychiatry Res. 2007;152:243–52. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2007.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bennett P, Brooke S. Intrusive memories, post-traumatic stress disorder and myocardial infarction. Br J Clin Psychol. 1999;38(Pt 4):411–6. doi: 10.1348/014466599163015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bennett P, Conway M, Clatworthy J, Brooke S, Owen R. Predicting post-traumatic symptoms in cardiac patients. Heart Lung. 2001;30:458–65. doi: 10.1067/mhl.2001.118296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bennett P, Owen RL, Koutsakis S, Bisson J. Personality, social context and cogni-tive predictors of posttraumatic stress disorder in myocardial infarction patients. Psychol Health. 2002;17:489–500. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chung MC, Dennis I, Berger Z, Jones R, Rudd H. Posttraumatic stress disorder following myocardial infarction: Personality, coping, and trauma exposure characteristics. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2011;42:393–419. doi: 10.2190/PM.42.4.e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kutz I, Shabtai H, Solomon Z, Neumann M, David D. Post-traumatic stress disorder in myocardial infarction patients: Prevalence study. Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci. 1994;31:48–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Whitehead DL, Perkins-Porras L, Strike PC, Steptoe A. Post-traumatic stress disorder in patients with cardiac disease: Predicting vulnerability from emotional responses during admission for acute coronary syndromes. Heart. 2006;92:1225–9. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2005.070946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hari R, Begré S, Schmid JP, Saner H, Gander ML, von Känel R. Change over time in posttraumatic stress caused by myocardial infarction and predicting variables. J Psychosom Res. 2010;69:143–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2010.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ginzburg K, Ein-Dor T. Posttraumatic stress syndromes and health-related quality of life following myocardial infarction: 8-year follow-up. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2011;33:565–71. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2011.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ginzburg K, Solomon Z, Koifman B, Keren G, Roth A, Kriwisky M, et al. Trajectories of posttraumatic stress disorder following myocardial infarction: A prospective study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64:1217–23. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v64n1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pedersen SS, Middel B, Larsen ML. Posttraumatic stress disorder in first-time myocardial infarction patients. Heart Lung. 2003;32:300–7. doi: 10.1016/s0147-9563(03)00097-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guler E, Schmid JP, Wiedemar L, Saner H, Schnyder U, von Känel R. Clinical diagnosis of posttraumatic stress disorder after myocardial infarction. Clin Cardiol. 2009;32:125–9. doi: 10.1002/clc.20384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Meister R, Princip M, Schmid JP, Schnyder U, Barth J, Znoj H, et al. Myocardial infarction – Stress PRevention INTervention (MI-SPRINT) to reduce the incidence of posttraumatic stress after acute myocardial infarction through trauma-focused psychological counseling: Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2013;14:329. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-14-329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.von Känel R, Schmid JP, Abbas CC, Gander ML, Saner H, Begré S. Stress hormones in patients with posttraumatic stress disorder caused by myocardial infarction and role of comorbid depression. J Affect Disord. 2010;121:73–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Meewisse ML, Reitsma JB, de Vries GJ, Gersons BP, Olff M. Cortisol and post-traumatic stress disorder in adults: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2007;191:387–92. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.106.024877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shalev AY, Sahar T, Freedman S, Peri T, Glick N, Brandes D, et al. A prospective study of heart rate response following trauma and the subsequent development of posttraumatic stress disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55:553–9. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.6.553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shalev AY, Yehuda R. Longitudinal development of traumatic stress disorders. In: Yehuda R, editor. Psychological. Trauma: American Psychiatric Press; 1998. pp. 31–6. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rohleder N, Karl A. Role of endocrine and inflammatory alterations in comorbid somatic diseases of post-traumatic stress disorder. Minerva Endocrinol. 2006;31:273–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sack M, Hopper JW, Lamprecht F. Low respiratory sinus arrhythmia and prolonged psychophysiological arousal in posttraumatic stress disorder: Heart rate dynamics and individual differences in arousal regulation. Biol Psychiatry. 2004;55:284–90. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00677-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cohen H, Kotler M, Matar MA, Kaplan Z, Miodownik H, Cassuto Y. Power spectral analysis of heart rate variability in posttraumatic stress disorder patients. Biol Psychiatry. 1997;41:627–9. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(96)00525-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Reed MJ, Robertson CE, Addison PS. Heart rate variability measurements and the prediction of ventricular arrhythmias. QJM. 2005;98:87–95. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hci018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tracey KJ. The inflammatory reflex. Nature. 2002;420:853–9. doi: 10.1038/nature01321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McEwen BS. Protective and damaging effects of stress mediators. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:171–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199801153380307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.von Känel R, Hepp U, Buddeberg C, Keel M, Mica L, Aschbacher K, et al. Altered blood coagulation in patients with posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychosom Med. 2006;68:598–604. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000221229.43272.9d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Baker DG, Ekhator NN, Kasckow JW, Hill KK, Zoumakis E, Dashevsky BA, et al. Plasma and cerebrospinal fluid interleukin-6 concentrations in posttraumatic stress disorder. Neuroimmunomodulation. 2001;9:209–17. doi: 10.1159/000049028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Danesh J, Kaptoge S, Mann AG, Sarwar N, Wood A, Angleman SB, et al. Long-term interleukin-6 levels and subsequent risk of coronary heart disease: Two new prospective studies and a systematic review. PLoS Med. 2008;5:e78. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.von Känel R, Hepp U, Kraemer B, Traber R, Keel M, Mica L, et al. Evidence for low-grade systemic proinflammatory activity in patients with posttraumatic stress disorder. J Psychiatr Res. 2007;41:744–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2006.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Markovitz JH, Matthews KA, Kiss J, Smitherman TC. Effects of hostility on platelet reactivity to psychological stress in coronary heart disease patients and in healthy controls. Psychosom Med. 1996;58:143–9. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199603000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Solter V, Thaller V, Karlovic D, Crnkovic D. Elevated serum lipids in veterans with combat-related chronic posttraumatic stress disorder. Croat Med J. 2002;43:685–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Finney ML, Stoney CM, Engebretson TO. Hostility and anger expression in African American and European American men is associated with cardiovascular and lipid reactivity. Psychophysiology. 2002;39:340–9. doi: 10.1017/s0048577201393101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Boscarino JA, Chang J. Electrocardiogram abnormalities among men with stress-related psychiatric disorders: Implications for coronary heart disease and clinical research. Ann Behav Med. 1999;21:227–34. doi: 10.1007/BF02884839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Grace SL, Abbey SE, Kapral MK, Fang J, Nolan RP, Stewart DE. Effect of depression on five-year mortality after an acute coronary syndrome. Am J Cardiol. 2005;96:1179–85. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.06.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Goodwin RD, Davidson JR. Self-reported diabetes and posttraumatic stress disorder among adults in the community. Prev Med. 2005;40:570–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Beckham JC, Kirby AC, Feldman ME, Hertzberg MA, Moore SD, Crawford AL, et al. Prevalence and correlates of heavy smoking in Vietnam veterans with chronic posttraumatic stress disorder. Addict Behav. 1997;22:637–47. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(96)00071-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Alonzo AA, Reynolds NR. The structure of emotions during acute myocardial infarction: A model of coping. Soc Sci Med. 1998;46:1099–110. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(97)10040-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pedersen SS. Post-traumatic stress disorder in patients with coronary artery disease: A review and evaluation of the risk. Scand J Psychol. 2001;42:445–51. doi: 10.1111/1467-9450.00257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wiedemar L, Schmid JP, Müller J, Wittmann L, Schnyder U, Saner H, et al. Prevalence and predictors of posttraumatic stress disorder in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Heart Lung. 2008;37:113–21. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2007.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ahmadi N, Hajsadeghi F, Mirshkarlo HB, Budoff M, Yehuda R, Ebrahimi R. Post-traumatic stress disorder, coronary atherosclerosis, and mortality. Am J Cardiol. 2011;108:29–33. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2011.02.340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Edmondson D, Rieckmann N, Shaffer JA, Schwartz JE, Burg MM, Davidson KW, et al. Posttraumatic stress due to an acute coronary syndrome increases risk of 42-month major adverse cardiac events and all-cause mortality. J Psychiatr Res. 2011;45:1621–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2011.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Carney RM, Blumenthal JA, Catellier D, Freedland KE, Berkman LF, Watkins LL, et al. Depression as a risk factor for mortality after acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 2003;92:1277–81. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2003.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yehuda R. Post-traumatic stress disorder. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:108–14. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra012941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kubzansky LD, Koenen KC, Spiro A, 3rd, Vokonas PS, Sparrow D. Prospective study of posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms and coronary heart disease in the Normative Aging Study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:109–16. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.1.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yehuda R. Psychoneuroendocrinology of post-traumatic stress disorder. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 1998;21:359–79. doi: 10.1016/s0193-953x(05)70010-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Doerfler LA, Pbert L, DeCosimo D. Symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder following myocardial infarction and coronary artery bypass surgery. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1994;16:193–9. doi: 10.1016/0163-8343(94)90101-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Stoll C, Schelling G, Goetz AE, Kilger E, Bayer A, Kapfhammer HP, et al. Health-related quality of life and post-traumatic stress disorder in patients after cardiac surgery and intensive care treatment. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2000;120:505–12. doi: 10.1067/mtc.2000.108162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Oxlad M, Wade TD. Application of a chronic illness model as a means of understanding pre-operative psychological adjustment in coronary artery bypass graft patients. Br J Health Psychol. 2006;11(Pt 3):401–19. doi: 10.1348/135910705X37289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Juergens MC, Seekatz B, Moosdorf RG, Petrie KJ, Rief W. Illness beliefs before cardiac surgery predict disability, quality of life, and depression 3 months later. J Psychosom Res. 2010;68:553–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2009.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Frasure-Smith N, Lespérance F, Talajic M. Depression and 18-month prognosis after myocardial infarction. Circulation. 1995;91:999–1005. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.91.4.999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Shemesh E, Rudnick A, Kaluski E, Milovanov O, Salah A, Alon D, et al. A prospective study of posttraumatic stress symptoms and nonadherence in survivors of a myocardial infarction (MI) Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2001;23:215–22. doi: 10.1016/s0163-8343(01)00150-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Boyer BA, Knolls ML, Kafkalas CM, Tollen LG. Prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder in patients with pediatric spinal cord injury: Relationship to functional independence. Top Spinal Cord Inj Rehabil. 2000;6:125–33. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Stein MB, Kerridge C, Dimsdale JE, Hoyt DB. Pharmacotherapy to prevent PTSD: Results from a randomized controlled proof-of-concept trial in physically injured patients. J Trauma Stress. 2007;20:923–32. doi: 10.1002/jts.20270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Famularo R, Kinscherff R, Fenton T. Propranolol treatment for childhood posttraumatic stress disorder, acute type. A pilot study. Am J Dis Child. 1988;142:1244–7. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1988.02150110122036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]