Abstract

Background:

Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD) is a chronic, distressing, anxiety disorder associated with significant functional impairment. Patient with OCD often suffer from one or more co-morbid disorders. Major depression has been the most common co-morbid syndrome. Comorbid Axis I disorders along with increased severity of comorbid depressive and anxiety symptoms, increased severity of obsessions, feelings of hopelessness and past history of suicide attempts have been associated with worsening levels of suicidality in OCD (Angelakis I, Gooding P., 2015). As per data Thirty-six percent of the patients of OCD report lifetime suicidal thoughts and 11% have a history of attempted suicide(Torres AR, Ramos-Cerqueira AT, et al, 2011). There is a reasonable probability that the patient of OCD have suicidal thoughts, plans or actually attempt suicide.

Aim:

To assess depression and suicidality in OCD patients.

Method:

This study was conducted on 50 patients diagnosed with OCD as per ICD 10 criteria, both outpatient & indoor, from department of psychiatry, Dayanand Medical College & Hospital, Ludhiana, Punjab, India. A socio-demographic proforma (containing demographic details), Hamilton Depression Rating & Scale, Columbia suicide severity rating scale (CSSRS) & Yale Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale Symptom Checklist (YBOCS) were administered.

Results:

Mild depression was found out to be 40% whereas 16% were suffering from moderate depression and 10% and 14% had severe and very severe depression respectively. Suicidal ideation was found in 52 % of patients.16% of patients had history of actual attempt. Data showed that 70% of females had suicidal ideations. It was also found that in cases of severe and very severe depression associated with OCD all the patients had suicidal ideations as compared to 35% in mild and 87.5% in moderate depressive patients. It was found that 40% of severe depressive and 28.57% of very severe depressive patients had attempted suicide one or more times during the course of illness. Also suicidality was found to be maximum in those with symptoms of cleanliness and contamination (57%) followed by religious obsessions (45%), sexual obsessions (33%), repeated rituals (31%) and other obsessions like need to touch, ask (26%) respectively.

Conclusion:

OCD is associated with high risk not only depression but also of suicidal behavior. It is vital that patients of OCD undergo detailed assessment for suicide risk and associated depression. Aggressive treatment of depression may be warranted to modify the risk of suicide. Behavioral and cognitive techniques along with pharmacotherapy should be used to target co-existing depressive symptoms so as to decrease morbidity and mortality.

Keywords: Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD), Depression, Suicidality

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) is a chronic, distressing, anxiety disorder associated with a significant functional impairment. OCD has emerged to be one of the most prominent and disabling mental disorders. OCD is an anxiety disorder characterized by recurrent obsession or compulsions that are recognized as excessive or unreasonable causing a marked distress, are time-consuming (>1 h/day), interfere with normal function, and are egodystonic. It is the fourth most common psychiatric disorder.[1] Epidemiological studies across the world have estimated the lifetime prevalence of OCD to be ranging from 1.9% to 3.3%.[2]

Patients with OCD often suffer from one or more comorbid disorders. In the last few years, there has been another important paradigm shift, leading to the crucial hypothesis that OCD may be an etiologically heterogeneous condition, therefore being affected by a wide spectrum of comorbidities. Individuals with OCD frequently have additional psychiatric disorders concomitantly or at some time during their lifetime. Recently, some authors proposed an OCD subclassification based on comorbidity. The authors proposed a three-class solution characterized by: (1) An OCD simplex class, in which major depressive disorder (MDD) is the most frequent additional disorder, (2) an OCD comorbid tic-related class, in which tics are prominent and affective syndromes are considerably rarer, and (3) an OCD comorbid affective-related class, in which panic disorder and affective syndromes are highly presented.[3]

Major depression has been the most common comorbid syndrome. The lifetime prevalence of depression in patients with OCD is reported between 12% and 70%, whereas the lifetime prevalence of comorbid anxiety disorders in patients with OCD was noticed to be 25%–75%. Comorbid Axis I disorders along with increased severity of comorbid depressive and anxiety symptoms, increased severity of obsessions, feelings of hopelessness, and history of suicide attempts have been associated with worsening levels of risk of suicide in OCD.[4] As per data, 36% of patients of OCD reported lifetime suicidal thoughts and 11% have a history of attempted suicide.[2] Suicidal behavior is defined as an act through which an individual harms himself/herself (self-aggression) whatever may be the degree of lethal intention or recognition of genuine reason for their action.[5,6] There is a reasonable probability that the patients of OCD have suicidal thoughts, plans, or actually attempt suicide. Suicidal behavior is the result of a complex interaction of biological, genetic, psychological, sociological, and environmental factors.

OCD is associated with a high risk for suicidal behavior. Depression and hopelessness are the major correlates of suicidal behavior. The present study aims to identify these symptoms and ensures a better outcome.

Aim

The study aims to assess depression and risk of suicide in patients with OCD in a tertiary care hospital.

METHODS

The present study was conducted on fifty patients diagnosed with OCD as per the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision criteria, both outpatient and indoor, from the Department of Psychiatry, Dayanand Medical College and Hospital, Ludhiana, Punjab, India. An informed consent was obtained before enrolling patients for the study. Those having a significant medical condition and those with a comorbid psychotic illness or substance use disorder were excluded from the study. A sociodemographic pro forma containing demographic details (age, sex, educational qualification, and marital status) was used. Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D) for the assessment of severity of depressive symptoms, Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale (CSSRS) for the assessment of risk of suicide, and Yale–Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale to have a knowledge of the types of obsessions and compulsions present in the cases were administered.

RESULTS

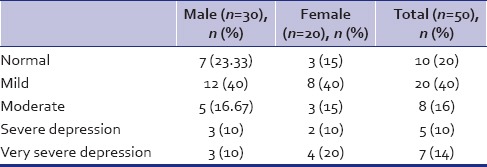

The study sample had fifty cases, of which thirty were male and twenty were female. In our study, we have evaluated the depressive symptoms with the help of HAM-D and the results obtained have been tabulated in Table 1. It shows that 80% of the cases had depressive symptoms. Of those, 40% had mild depression, whereas 16% of the patients were suffering from moderate depression and 10% and 14% had severe and very severe depression, respectively. Of the male cases, only 10% had severe depression and another 10% had very severe depression as compared to females with 10% having severe and 20% having very severe depression.

Table 1.

Severity of depression on Hamilton Depression Rating Scale in patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder

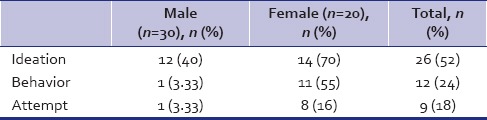

On applying CSSRS, suicidal ideation was found in 52% of patients as depicted in Table 2. Nearly 24% had suicidal behavior and 18% of patients had a history of actual attempt. Data showed that 70% of females had suicidal ideations when compared to 40% of males. About 3.33% of the males had actually attempted suicide, while in the case of females, it was 16% much higher than males.

Table 2.

Risk of suicide on Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale

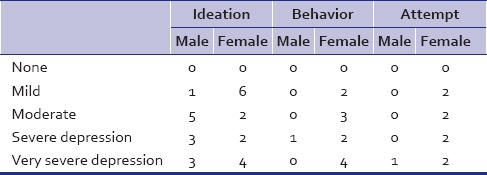

Table 3 relates the risk of suicide on CSSRS with that of the severity of depressive symptoms on HAM-D in patients with OCD. It was found that, in cases of severe and very severe depression associated with OCD, all the patients had suicidal ideations as compared to 35% in mild and 87.5% in moderate depressive patients. It was found that 40% of severe depressive and 42.857% of very severe depressive patients had attempted suicide one or more times during illness.

Table 3.

Comparison of depressive symptoms (on Hamilton Depression Rating Scale) with the risk of suicide (on Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale)

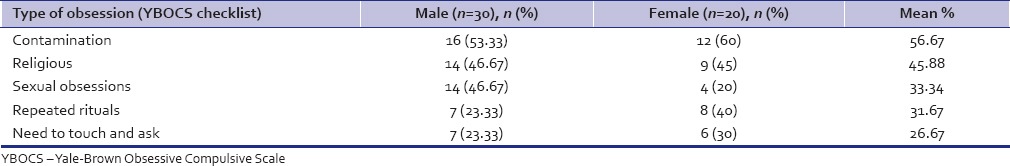

Risk of suicide was found to be maximum in those with symptoms of cleanliness and contamination (57%) followed by religious obsessions (45%), sexual obsessions (33%), repeated rituals (31%), and other obsessions such as need to touch and ask (26%) as shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale symptom checklist and risk of suicide in patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder

DISCUSSION

In our study, 60% of sample comprised male patients, while female gender comprised 40% only. This is in conformity with the general trends observed at various psychiatric outpatient departments (OPDs) from where the patients are selected. This may be due to the cultural factors that promote a greater health-seeking behavior in men resulting in a greater attendance at the OPD and women being the neglected and less cared for.

As per our study, 80% of the cases had comorbid depression of varying intensities. While up to 60%–80% of patients with OCD experience a depressive episode in their lifetime, most studies agree that at least one-third of patients with OCD have concurrent MDD at the time of evaluation.[7,8] This coexistence of major depression with OCD has been found to be related to chronicity and severity of obsessive-compulsive symptoms leading to disabling the patients from doing their daily routine activities. Since there is no viable physical disorder or disease, patient is not getting social support to face his/her problem which may cause hopelessness and worthlessness leading to depression. These findings are also reported in literature.[9] A recent study that compared depressive symptoms of pure MDD with those from OCD complicated with depressive symptoms of equal severity showed that patients suffering from both OCD and MDD scored significantly and substantially higher on the Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale items for anxiety and pessimistic thoughts.[10]

On the scale for suicide, 52% had suicidal ideations and 18% had actually attempted suicide in our study. This indicates that those 52% of the patients in the study had recently contemplated about ending their lives. This is significant and scary because the clinician overlooks the possible suicidal threat of the patient because symptomatic treatment has become the center of focus while treating patients with OCD and is comparable to that in depressive disorder itself where studies have shown similar incidence of suicidal ideations.[11]

In our sample, 24% of patients had suicidal behavior and 18% had a history of the actual attempt. It has been observed that a history of suicidal attempt in the past is considered to be a strong predictor for future suicidal attempts.[12,13] Comparatively similar predictors emerged as significant for the current suicidal ideations, with an overall prediction of 85% in an Indian study.

In the present study, past suicidal attempts were present in 18% of patients, and this is significantly higher than the attempted suicidal rates in the general population in India. The rate in the general population in different parts of India ranges from 8.1 to 58.3 per 1 lakh.[14] The suicide attempt rates reported in our study are comparable to that in other disorders which have an established relationship with suicidal behavior. Lifetime suicidal attempt rates in unipolar disorders were found to be 15.9%.[15] This indicates that risk of suicide in OCD is comparable to that in other major psychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia and depression, indicating more active treatment strategies to decrease morbidity and mortality due to OCD.

The incidence of suicidal attempts was more in female, i.e. 16% compared to males (3.33%). This is in synchronization with the knowledge available that suicidal attempts are more common in female gender. Similar findings of a higher incidence of suicidal attempt among females have been reported in other studies, while high rates of completed suicides are reported among men.[16,17]

On relating the findings of HAM-D with that of CSSRS, it was found that 40% of severe depressive and 42.857% of very severe depressive patients had attempted suicide one or more times during illness. Thus, indicating that HAM-D scores act as significant predictors of risk of suicide. The same was shown in another study where HAM-D score was a significant predictor of suicide in OCD, with an overall prediction of 82%.[18] These findings alarm us to consider a detailed evaluation of depression and suicidal risk and consider treatment strategies focusing these areas.

It was found that aggressive, philosophical, existential, odd, or superstitious obsessions are more common in patients with both OCD and MDD and that sexual and religious obsessions are more frequent in patients with comorbid recurrent MDD.[19] This is very much similar to the findings of our study which shows an increased prevalence of risk of suicide in those with symptoms of cleanliness and contamination (57%) followed by religious obsessions (45%), sexual obsessions (33%), repeated rituals (31%), and other obsessions such as need to touch and ask (26%).

The findings of the present study suggest that there is a significant risk of suicide among the patients of OCD. This is noteworthy that depression is common comorbidity with OCD and is a risk factor for suicide in itself.

CONCLUSION

OCD is associated with a high risk not only of depression but also of suicidal behavior. Behavioral and cognitive techniques along with pharmacotherapy should be used to target coexisting depressive symptoms so as to decrease morbidity and mortality. It is vital that patients of OCD undergo a detailed assessment for suicide risk and associated depression. Aggressive treatment of depression may be warranted to modify the risk of suicide.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Karno M, Golding JM, Sorenson SB, Burnam MA. The epidemiology of obsessive-compulsive disorder in five US communities. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1988;45:1094–9. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1988.01800360042006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zohar AH, Ratzoni G, Pauls DL, Apter A, Bleich A, Kron S, et al. An epidemiological study of obsessive-compulsive disorder and related disorders in Israeli adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1992;31:1057–61. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199211000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nestadt G, Di CZ, Riddle MA, Grados MA, Greenberg BD, Fyer AJ, et al. Obsessive-compulsive disorder: Subclassification based on co-morbidity. Psychol Med. 2009;39:1491–501. doi: 10.1017/S0033291708004753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Angelakis I, Gooding P, Tarrier N, Panagioti M. Suicidality in obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD): A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2015;39:1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2015.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization. Multisite Intervention Study on Suicidal Behaviors, SUPRE-MISS. Geneva: WHO; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maris RW. Suicide. Lancet. 2002;360:319–26. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09556-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Perugi G, Akiskal HS, Pfanner C, Presta S, Gemignani A, Milanfranchi A, et al. The clinical impact of bipolar and unipolar affective comorbidity on obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Affect Disord. 1997;46:15–23. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(97)00075-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tükel R, Polat A, Ozdemir O, Aksüt D, Türksoy N. Comorbid conditions in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Compr Psychiatry. 2002;43:204–9. doi: 10.1053/comp.2002.32355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Angst J, Gamma A, Endrass J, Hantouche E, Goodwin R, Ajdacic V, et al. Obsessive-compulsive syndromes and disorders: Significance of comorbidity with bipolar and anxiety syndromes. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2005;255:65–71. doi: 10.1007/s00406-005-0576-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fineberg NA, Fourie H, Gale TM, Sivakumaran T. Comorbid depression in obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD): Symptomatic differences to major depressive disorder. J Affect Disord. 2005;87:327–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2005.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sokero TP, Melartin TK, Rytsälä HJ, Leskelä US, Lestelä-Mielonen PS, Isometsä ET. Suicidal ideation and attempts among psychiatric patients with major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64:1094–100. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v64n0916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beck AT, Steer RA, Kovacs M, Garrison B. Hopelessness and eventual suicide: A 10-year prospective study of patients hospitalized with suicidal ideation. Am J Psychiatry. 1985;142:559–63. doi: 10.1176/ajp.142.5.559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harris EC, Barraclough B. Suicide as an outcome for mental disorders. A meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 1997;170:205–28. doi: 10.1192/bjp.170.3.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gururaj G, Isaac MK. Epidemiology of Suicide in Bangalore. Publication No. 43. Bangalore: National Institute of Mental Health and Neuro Sciences; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen YW, Dilsaver SC. Lifetime rates of suicide attempts among subjects with bipolar and unipolar disorders relative to subjects with other axis I disorders. Biol Psychiatry. 1996;39:896–9. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(95)00295-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Andrews JA, Lewinsohn PM. Suicidal attempts among older adolescents: Prevalence and co-occurrence with psychiatric disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1992;31:655–62. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199207000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Simons RL, Murphy PI. Sex differences in the causes of adolescent suicide ideation. J Youth Adolesc. 1985;14:423–34. doi: 10.1007/BF02138837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kamath P, Reddy YC, Kandavel T. Suicidal behavior in obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68:1741–50. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v68n1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hong JP, Samuels J, Bienvenu OJ, 3rd, Cannistraro P, Grados M, Riddle MA, et al. Clinical correlates of recurrent major depression in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Depress Anxiety. 2004;20:86–91. doi: 10.1002/da.20024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]