Abstract

Background:

Past research studies on the exploration of attributes to the stress of doctors/medical interns were reported more often than the types of coping strategies, healthy practices to strengthen their internal resources to deal effectively with the stressful situations.

Objectives:

The present study was conducted to find such internal resource – “mindfulness” as a mediator of coping, perceived stress, and job satisfaction among medical interns.

Methods:

A cross-sectional descriptive study comprised 120 medical interns forms from various medical colleges in Mangalore were recruited and completed the assessment on mindfulness, cognitive-emotive regulation, coping strategies, perceived stress, and job satisfaction from doctoral interns were collected.

Results:

Initial correlation analysis results indicate that adaptive coping strategies significantly associate with greater mindfulness and less perceived stress. In turn, mindfulness is negatively correlated with nonadaptive coping strategies and perceived. Job satisfaction showed no significant relationship with any of the other variables. Mediational models indicate that the relationship between adaptive coping strategies and perceived stress was significantly mediated by mindfulness. Furthermore, partial mediation between nonadaptive strategies and perceived stress through mindfulness indicates that respondents reported a high level of nonadaptive strategy experience and a lower level of mindfulness can be counterproductive as they encourage the ineffective way to deal with the stresses.

Conclusion:

The implication of the results were discussed with suggesting a possible intervention to improve the adaptive strategies and mindfulness among the medical interns.

Keywords: Coping, job satisfaction, medical interns, mindfulness, perceived stress

Since the latter part of the 20th century is known for the modern medicines and technology, the life span is effectively increased by treating the ailments which extremely affect the physical health. Consequently, the ratio of research studies on doctors is more predominantly tilted toward determinants of doctor's success stories than exploration on the amount of stress they experience and its affects their success ratio in the treatment.[1] Occupational stress is “any discomfort which is felt and perceived at a personal level and triggered by instances, events, or situations that are too intense and frequent in nature so as to exceed a person's coping capabilities and resources to handle them adequately.”[2] The preponderance of research studies encapsulates the effects of stress and stress-related illnesses such as anxiety and depression among students, trainees, and qualified physicians.[3,4] Certainly, some research shows the unique academic challenges of medical studies, rigor of the academic program, and emotionally tense experiences, such as dealing with illness, disease, and dying that make medical students reflect the more prevalent kind of psychological distress, and they are more vulnerable to stress and anxiety than students of other disciplines.[5,6,7] In the same way, stress in health professionals is high, with 28% showing above threshold symptoms compared to 18% of workers as a whole in the UK. Between 10% and 20% of doctors in the UK become depressed at some time during their career, and the risk of suicide is raised compared to the general population.[8] Evidence from Switzerland suggests that levels of burnout among doctors are high.[9] In the Indian context, similar studies have been conducted, but the studies were mediocre in stating the underpinning mechanisms of stress buffers.[3,10,11]

Large bodies of research in the last few decades have provided evidence that the prevalence of perceived stress among medical students was high.[12,13,14,15] It has been proposed that residency comprises a particularly stressful period during the doctors training since, except for their immediate “survival” needs, they have also to cover educational and patient care needs. Given the psychological toll which young doctors pay, due to this difficult combination, it is a great effort to achieve the basic aim of their 1st year in practice, which is the acquisition of necessary knowledge and experience.[16] Following this, a study indicated that the degree of stress was significantly higher among interns as compared to 1st, 2nd, and 3rd year MBBS students. Besides academic stressors, social and emotional stresses and physical stressors were the predominant factors contributing to stress in these groups as compared to others.[17] The consequence of the stress has many facets such as decrease in their academic performance.[18,19] Subsequently, affect in decision-making skill of students[20] and the high incidence of depression have also been reported.[21] Stress in medical students is receiving attention because it has been recognized that tired, tense doctors may not provide high-quality care.[8] Studies have also reported other negative consequences of stress, and there have been multiple calls for to protect against stress.[14] A study stated that stress and the effects of long-term stress (i.e., burnout) are two of the leading causes of physical and emotional illness, poor job performance and poor job satisfaction, poor family, peer and coworker relations, as well as decreased life satisfaction and general well-being.[22] Over the years, studies have shown that experiencing stress in the work setting leads to undesirable consequences on the well-being and safety of an individual and invariably for the organization. Occupational stress leads to reduced productivity and performance, increased sickness and absenteeism, decreased motivation, and morale among employees. As a result, it creates an insight among researchers to assess what constitutes effective measures, to take appropriate corrective action to promote well-being in health professional, by preventing them from experiencing stress.[23]

”Cope is the constantly changing cognitive and behavioral efforts to manage specific external and/or internal demands that are appraised as taxing or exceeding the resources of the person.”[24] People use various methods or rather strategies, both cognitive and behavioral, in their attempt to tolerate, reduce, or minimize stressful events. Coping strategies come under two broad classifications, i.e., adaptive and maladaptive coping strategies. The problem-focused forms of coping (so-called adaptive) are likely to be associated with lower levels of negative health outcomes which caused by stressors and that coping of an emotional-focused (nonadaptive) types, such as self-blame, rumination, or escape/avoidance is likely to be associated with increased negative health.[24] Coping is a vital part of any person's survival in today's fast-paced health-care environment. It is noted that “coping serves two overriding functions: managing or altering the problem with the environment causing distress (problem-focused coping) and regulating the emotional response to the problem (emotion-focused coping).”[25] The choice of coping options is determined by internal and external factors. Personal agenda (e.g., beliefs, values, and experience) and resources (e.g., financial or social support) influence the outcome. Coping behaviors are generally classified as problem-oriented (long-term) or affective-oriented (short-term) methods. The problem-oriented strategies are those used to solve stress-producing problems whereas the affective-oriented manage the emotional component involved. Short-term coping methods (eating, sleeping, and smoking) reduce tension temporarily but do not deal directly with the stressful situation. Drawing on past experience and talking it out with others are examples of long-term stress reduction methods. The problem-oriented strategies are seen as constructive ways of dealing with stress.[26]

The key to successfully master or minimize stress highly depends on using adaptive coping strategies which emphasize the need to expend conscious effort on the individual's part. This conscious effort required refers to being “mindful” of one's problem, solutions, environment, i.e., being completely and consciously aware of what is happening in and around the individual at every given moment. The mindfulness and its association with different coping strategies and styles found that higher mindfulness predicts the use of more adaptive, approach coping and less avoidant and emotional coping. According to recent studies, mindfulness practice which is the cultivation of a focused awareness on the present moment can improve physician performance by not only preventing burn out but by also helping them better connect with their patients.[27] Mindfulness has been associated with a number of physical and mental health benefits, including lower levels of stress, improved cognitive functioning, etc., all this invariably has a direct positive effect on the job satisfaction of an individual. A study among workers in service industries, researchers' hypotheses that working environments tend to be demanding the employees to fake their emotions at work is also called as “surface acting.” The results show that people vary both in how mindful they are at any given time (state mindfulness) as well as how mindful they are overall (trait mindfulness). Indeed, the level of mindfulness also predicts job satisfaction and emotional exhaustion, with higher levels of mindfulness resulting in greater job satisfaction and less emotional exhaustion.[28]

Irrespective of the knowledge that medical interns as their superiors in the health-care professionals are under an immense amount of pressure and stress, which may invariably harm their job satisfaction, troubled personal relationships, and may even cause depression and suicide in some of these professionals, there has not been a satisfactory amount of research on the sample. Stress may also be a hindrance to their professional effectiveness as it reduces attention and concentration and at times may cause a kind of blockage in establishing adequate relationships with their respective patients. The study can be used to find how coping, mindfulness, and perceived stress together affect the job satisfaction of medical interns.

METHODS

The samples for this study consisted of 120 medical interns (50.2% female and 49.8% male), who were at present posted at various institutions as part of the compulsory rotatory internship in Mangalore medical colleges. All respondents were subjected to shift work. The sample was selected behind the rationale that internship period is proposed to be a particularly stressful period during the doctors training since, except for their immediate “survival” needs they have also to cover educational and patient care. Participant's age ranged from 22 to 25 years with a mean age of male sample is 23.69 (standard deviation [SD] = 0.95) and female is 23.78 (SD = 0.89).

Design and procedure

A cross-sectional descriptive design was utilized to test the research hypothesis. Participants were selected by random sampling method and administered three self-report inventories, namely, Cognitive Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (CERQ), Mindfulness Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS), Perceived Stress Scale (PSS), and Job Satisfaction Scale. During the administration, appropriate instructions were given to them by stating the aim and objectives of the proposed study. Before proceeding to the main study, due permission was obtained from the concern college authority. The participants were assured that the individual anonymity of the individual responses will be preserved, and only the summarized results were reported.

Measures

Cognitive Emotion Regulation Questionnaire

CERQ[29] is a 36-item questionnaire with a 5-point Likert response format (1 - almost never to 5 - almost always) designed to evaluate the cognitive aspects of emotional regulation. The questionnaire is introduced by the following sentences, which are written at the top: “Everyone gets confronted with negative or unpleasant events now and then and everyone responds to them in his/her own way”. With the following question, you are asked to indicate what you generally think when you experience negative or unpleasant events. This questionnaire consists of nine dimensions as follows:

Acceptance: Having thought of acceptance and resignation with regard to what one has experienced (e.g., I think that I have to accept that this has happened)

Positive refocusing: Having positive, happy, and pleasant thoughts instead of thinking about threatening and stressful events (e.g., I think of nicer things than what I have experienced)

Refocus on planning: Having thought about what to do and how to handle the experience one has had (e.g., I think of what I can do best)

Positive reappraisal: Having thought the goal of which is to give a positive meaning to the negative meaning events in terms of personal growth (e.g., I think I can learn something from the situation)

Putting into perspective: Having thoughts that realize the negative event compared to other events (e.g., I think that it all could have been much worse)

Self-blame: Having thoughts that blame oneself or what one has experienced (e.g., I feel that I am the one to blame for it)

Rumination: Having thoughts about the feelings and thoughts that are associated with negative events (e.g., I often think about how I feel about what I have experienced)

Catastrophizing: Having thoughts that emphasize the negativity of the experience (e.g., I continually think how horrible the situation has been)

Blaming others: Having thoughts that blame others for what one has experienced (e.g., I feel that others are to blame for it).

Mindful Attention Awareness Scale

MAAS[30] was designed to measure dispositional mindfulness, a general tendency in individuals to be aware of and attentive to present-moment experiences in daily life. The MAAS examines individual variations in the regularity of mindful states over time. Thus, this measure concentrates on the presence and acceptance as a state of mindful attention and awareness in the present moment, as opposed to other characteristics that have been associated with mindfulness. Respondents indicated on a 15-item questionnaire how often they experienced an incident described in each statement, using a 6-point Likert scale from 1 (almost always) to 6 (Almost never), for example, “I find it difficult to stay focused on what's happening in the present.” Developers of MAAS reported internal consistency of α = 0.86 (P < 0.001) while intercorrelation was reported as 0.95 (P < 0.001).

Perceived Stress Scale

The PSS[31] is the most widely used psychological mechanism for assessing perceptual stress, measuring the degree to which circumstances in one's life are judged as stressful.[32] Specific items were developed to extract the degree to which respondents perceive their lives as uncertain, uncontrollable, and overburdened. It is based on a 4-point Likert scale from 0 (never) to 4 (very often). Higher PSS scores denote higher perceived stress levels. This scale has been found to be a substantially reliable measurement tool (i.e., coefficient reliability = 0.84, 0.85, and 0.86, in three test samples) with high internal reliability (a = 0.78) and acceptable evidence of validity.

Job Satisfaction Scale

The Job Satisfaction Scale is a part of the Occupational Stress Indicator-2 (OSI-2).[33] The OSI-2 Section 1 – Job satisfaction (12 items measuring satisfaction toward the job itself and the organization; high scores indicate greater satisfaction); Section 2A – Mental well-being (12 items measuring contentment, resilience, and peace of mind; high scores denote greater well-being); Section 2B – Physical well-being (6 items measuring calmness and energy; high scores indicate better physical health); Section 3 – Sources of stress (40 items measuring workload, relationships, home/work balance, managerial role, personal responsibility, recognition, hassles, and organization climate; high scores indicate more sources of stress); and Section 4 – Coping strategies (10 items measuring control and support; high scores denote more frequent use of coping strategies). For this study, we have only taken Section 1 – Job satisfaction items from the OSI-2 questionnaire and internal consistency calculated for the current study shows that α =0.89, with alpha value indicating a high reliability.

Statistical analysis

The criteria outlined by Baron and Kenny provide a conceptual framework to facilitate examination of mediation, a test of statistical significance for the indirect effect of the mediator [Figures 1 and 2]. According to Baron and Kenny, mediation is indicated when the following conditions are met: (i) the independent variable has a significant effect on the mediator; (ii) independent variable has a significant effect on the dependent variable in the absence of the mediator; (iii) the mediator has a significant unique effect on dependent variable; and (iv) the effect of independent variable on dependent variable shrinks upon the addition of the mediator to the model.[34]

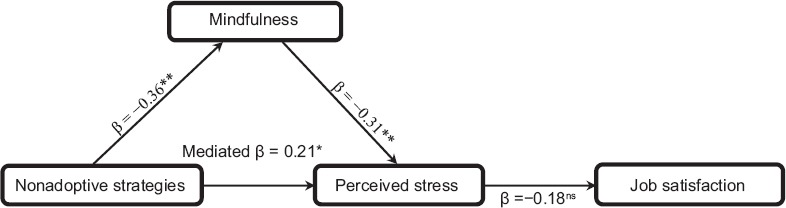

Figure 1.

Standardized regression coefficients for the relationship between adaptive coping strategies and perceived stress in job satisfaction as mediated by mindfulness

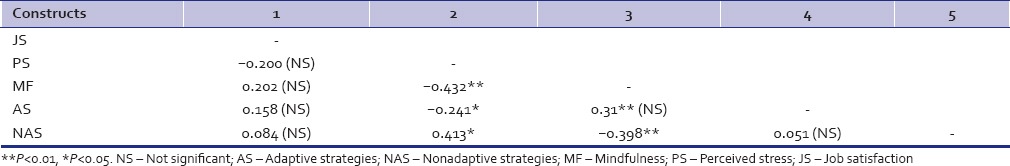

Figure 2.

Standardized regression coefficients for the relationship between nonadaptive coping strategies and perceived stress in job satisfaction as mediated by mindfulness

RESULTS

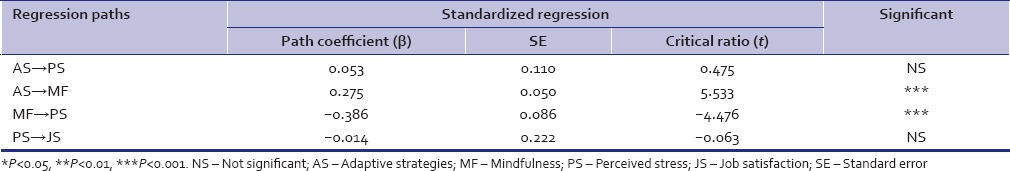

Table 1 shows the results obtained from the 120 medical interns who participated in the study, and it indicates that the variables perceived stress and nonadaptive strategies to cope are positively correlated with each other (r = 0.413, P < 0.01). Similar, adaptive strategies and mindfulness show a significant positive correlation coefficient r = 0.31 while adaptive strategies and perceived stress show a negative relationship (r = 0.254, P < 0.05). The criterion variable job satisfaction failed to show a statistically significant relationship with any of the other variables. The results further indicate that the mediating variable mindfulness is negatively correlated with perceived stress and nonadaptive strategies of coping (r = −0.432, P < 0.01; r = −0.398, P < 0.01).

Table 1.

Pearson's correlation coefficient between job satisfaction, perceived stress, mindfulness, adaptive strategies, and nonadaptive strategies (n=120)

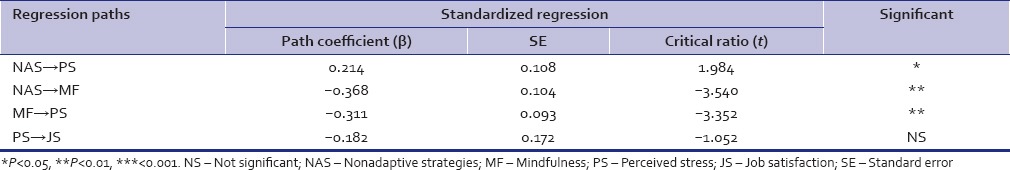

Table 2 shows the path coefficient between the independent, mediating, and criterion variable. The results revealed that adaptive coping strategies (β =0.053, t-value = 0.475) have an insignificant effect on perceived stress. It was evident that the adaptive coping strategies were associated significantly with the mindfulness (β =0.275, t-value = 5.533, P < 0.01). Similarly, mediating variable – mindfulness has exceeded the significant t-value (1.96) which implied that the construct had a significant negative effect on perceived stress. While considering the relationship between perceived stress and job satisfaction, results were insignificant (β = −0.014, t = −0.063).

Table 2.

Mediation results of adoptive coping, mindfulness, perceived stress and job satisfaction

Table 3 shows the path coefficient between the independent, mediating, and criterion variable. The results revealed that nonadaptive coping strategies (β = 0.214, t-value = 1.984) have a partial positive effect on perceived stress. It was evident that the nonadaptive coping strategies were negatively associated with the mindfulness (β = −0.568, t-value = −3.540, P < 0.05). Similarly, mediating variable – mindfulness shows a significant t-value (1.96) which implied that the construct had a significant negative effect on perceived stress. While considering the relationship between perceived stress and job satisfaction, results were insignificant (β = −0.182, t = −1.052).

Table 3.

Mediation results of nonadoptive coping, mindfulness, perceived stress and job satisfaction

DISCUSSION

Due to the lack of previous researches, this study was conducted on the population of medical interns, who are reported to have been facing a high level of stress during their course of the 1-year compulsory rotatory internship.[35] There have been little done by the institutions to train these students formally in adaptive coping strategies, which will help them deal with the stress faced by them effectively. If not taught adaptive coping strategies, the students may use nonadaptive strategies that could result in negatively affecting their work, social relationships, and other socioeconomic factors. This study was conducted to find if mindfulness acts as a mediating relationship to cope, perceived stress, and job satisfaction among medical interns. As the results elucidated, a negative relationship has been found between mindfulness and perceived stress. This could be attributed to the idea that when people are under immense pressure, they may use positive ways to deal with the pressure. “Mindfulness is a state in which you pay attention to the present without making judgments, negative or positive, about the feelings or thoughts you have.”[36] Individuals who use adaptive coping strategies such as refocus on planning, positive reappraisal, acceptance, etc., are better able to focus on the task at hand.

Hülsheger et al. found that people vary in both how mindful they are at any given time (state mindfulness) as well as how mindful they are overall (trait mindfulness). The level of mindfulness also predicted job satisfaction, with higher levels of mindfulness resulting in greater job satisfaction.[28] In addition, mindfulness training reduced the need to fake-positive emotions, causing job satisfaction to increase. It has been found that mindfulness has a significant negative relationship with nonadaptive strategies of coping. This could be ascribed to the reasoning that when an individual is stressed, they look at ways to deal with the present problematic situation effectively and as quickly as possible. In their hurry to deal with the situation, people tend to use methods that are not necessary adequate positive methods to deal with the problem but use it nonetheless. Those methods may negative in nature in that it deviates the person to deal effectively with the problem but rather helps them liberate themselves from it.

Perceived stress and nonadaptive strategy variables have been found to have a positive relationship. This could be attributed to the rigorous shift timings, immense demand for their undivided attention by patients as well as administrative duties that they are required to fulfill. The younger doctors are at a learning stage and have to struggle on a daily basis to gain excellence in their fields of specialization. Their duty rosters read night duties at least twice in a week. Hence, at initial stages, it becomes difficult for them to meet both the ends, i.e., familial as well as organizational.[10] With increased stress, there is a possibility of doctors being preoccupied, hence conscious efforts of the presence to the surrounding needs and requirements may be overlooked by them, which invariably lead to a decreased level of job satisfaction. Whereas physicians/doctors who have high levels of stress and use adaptive coping strategies along with mindfulness practice tend to be seen with decreased stress levels and higher job satisfaction. In support to the present findings, a recent study concluded that a significant proportion of doctors and doctor students were found to be dissatisfied with the average number of their work hours and salary. Factors such as the average number of work hours per day and the number of night shifts per month were found to have a significant relation with dissatisfaction and could lead to decreased job satisfaction.[11,37]

Overall, it can be derived that medical interns have a high level of stress, which may hinder their work and social environments; their methods of coping with this stress may not allow them to focus consciously on the here and now on the task at hand. For the benefit of medical interns, this study suggests that better coping and stress management must be taught to medical students during their coursework to prepare them mentally for their period of internship. Mindfulness training such as mindfulness meditation and mindfulness-based stress reduction training are certain methods that can be used by institutions to improve their students' level of being in the present moment that is being mindful.

Implications

A number of implications have emerged from the results of the present study. First, when a stressful adverse situation arises in the medical arena, some preventive strategies such as enhancement of intern's self-compassion, strengthening cognitive and emotional regulation coping mechanism (positive perception, appraisal and expression of emotion, emotional facilitation of thinking, understanding and analyzing emotion) may have a mitigating effect on the stress. Furthermore, cultivating mindfulness facilitates people to sustain in the present moment which involves consciously attending to and acceptance of cognitions, emotional states, and external experiences without sway away or judging those experiences.[38] By doing so, individual can create a mental space where one is able to think better, skillfully respond to intrusive thoughts, rather than react impulsively or reflexively through their habitual patterns of associated meaning, emotion, or behavior.[39,40] Subsequently, it is presumed that the level of psychological distress experienced by them may reduce sizably. Further, it is evident that medical interns with mindful disposition prefer relying on adaptive coping strategies such as acceptance, positive focusing, refocus on planning, positive reappraisal, and putting into perspective may facilitate to transform the cognitively negative event into a potential growth-generating experience. From a health point of view, it is expected that the interns who are engaged in problem-focused coping strategies generally demonstrate fewer indication of distress and maladjustment. Therefore, the introduction of mindfulness-based education programs may help to deal with stressors effectively. Furthermore, the benefit of developing an academic specific mindfulness training/module may enhance student's internal resources and can be implemented when the need arises. In consistent with research studies, the development of training programs can enhance individual's cognition and emotional regulations.[41]

Limitations

The present study had certain limitations such as (1) self-report data on mindfulness may be biased by affective response set and retrospective recall and (2) the sample sized used was limited, and a large sample may yield better significant relationships between the variables. The study was also limited to medical interns. To generalize this finding, further studies can be conducted among different population to deal with similar job stressors.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.McManus IC, Winder BC, Gordon D. The causal links between stress and burnout in a longitudinal study of UK doctors. Lancet. 2002;359:2089–90. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)08915-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Malta M. Stress at work, a concept in stress human factors limited. Bus Psychol Strategy Dev. 2004;33:125–33. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chakraborti A, Ray P, Sanyal D, Thakurta RG, Bhattacharayya AK, Mallick AK, et al. Assessing perceived stress in medical personnel: In search of an appropriate scale for the Bengali population. Indian J Psychol Med. 2013;35:29–33. doi: 10.4103/0253-7176.112197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rabkin JG, Struening EL. Live events, stress, and illness. Science. 1976;194:1013–20. doi: 10.1126/science.790570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dyrbye LN, Thomas MR, Harper W, Massie FS, Jr, Power DV, Eacker A, et al. The learning environment and medical student burnout: A multicentre study. Med Educ. 2009;43:274–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2008.03282.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murphy RJ, Gray SA, Sterling G, Reeves K, DuCette J. A comparative study of professional student stress. J Dent Educ. 2009;73:328–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Al-Sowygh ZH, Alfadley AA, Al-Saif MI, Al-Wadei SH. Perceived causes of stress among Saudi dental students. Saudi J Dent Res. 2013;4:7–15. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Firth-Cozens J. Doctors, their well-being, and their stress: It's time to be proactive about stress-and prevent it. BMJ. 2003;326:670. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7391.670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goehring C, Bouvier Gallacchi M, Künzi B, Bovier P. Psychosocial and professional characteristics of burnout in Swiss primary care practitioners: A cross-sectional survey. Swiss Med Wkly. 2005;135:101–8. doi: 10.4414/smw.2005.10841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nandi M, Hazra A, Sarkar S, Mondal R, Ghosal MK. Stress and its risk factors in medical students: An observational study from a medical college in India. Indian J Med Sci. 2012;66:1–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sharma B, Prasadz S, Pandeya R, Singh J, Sodhis KS, Wadhwa D. Evaluation of stress among post-graduate medical and dental students: A pilot study. Delhi Psychiatr J. 2013;16:312–6. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elzubeir MA, Elzubeir KE, Magzoub ME. Stress and coping strategies among Arab medical students: Towards a research agenda. Educ Health (Abingdon) 2010;23:355. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dahlin M, Joneborg N, Runeson B. Stress and depression among medical students: A cross-sectional study. Med Educ. 2005;39:594–604. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2005.02176.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shapiro SL, Shapiro DE, Schwartz GE. Stress management in medical education: A review of the literature. Acad Med. 2000;75:748–59. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200007000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barrows HS. Problem-based Learning: An Approach to Medical Education. New Yark: Springer Publishing Company; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Allen I. Committed but Critical: An Examination of Young Doctors Views of Their Core Values. British Medical Association, Health Policy and Economic Research Unit. 1997 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mohanty IR, Mohanty N, Balasubramanium P, Joseph D, Deshmuk Y. Assessment of stress, coping strategies and life style among medical students. Indian J Prev Soc Med. 2011;42:295–301. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stewart SM, Lam TH, Betson CL, Wong CM, Wong AM. A prospective analysis of stress and academic performance in the first two years of medical school. Med Educ. 1999;33:243–50. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.1999.00294.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dyrbye LN, Thomas MR, Shanafelt TD. Systematic review of depression, anxiety, and other indicators of psychological distress among U.S. and Canadian medical students. Acad Med. 2006;81:354–73. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200604000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Linn BS, Zeppa R. Stress in junior medical students: Relationship to personality and performance. Acad Med. 1984;59:7–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Niemi PM, Vainiomäki PT. Medical students' distress – Quality, continuity and gender differences during a six-year medical programme. Med Teach. 2006;28:136–41. doi: 10.1080/01421590600607088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Donald I, Taylor P, Johnson S, Cooper C, Cartwright S, Robertson S. Work environments, stress, and productivity: An examination using ASSET. Int J Stress Manag. 2005;12:409–23. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leape LL, Fromson JA. Problem doctors: Is there a system-level solution? Ann Intern Med. 2006;144:107–15. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-2-200601170-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress: Appraisal, and Coping. New York: Springer Publication; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Folkman S, Lazarus RS, Dunkel-Schetter C, DeLongis A, Gruen RJ. Dynamics of a stressful encounter: Cognitive appraisal, coping, and encounter outcomes. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986;50:992–1003. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.50.5.992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Keller KL. The management of stress and prevention of burnout in emergency nurses. J Emerg Nurs. 1990;16:90–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thomas C. A Review of the Relationships between Mindfulness, Stress, Coping Styles and Substance Use Among University Students. Edith Cowan University. 2011. [Cited on 2012 Jun 13]. Available from: http://www.ro.ecu.edu.au/theses_hons/33 .

- 28.Hülsheger UR, Alberts HJ, Feinholdt A, Lang JW. Benefits of mindfulness at work: The role of mindfulness in emotion regulation, emotional exhaustion, and job satisfaction. J Appl Psychol. 2013;98:310–25. doi: 10.1037/a0031313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Garnefski N, Kraaij V, Spinhoven P. Manual for the use of the Cognitive Emotion Regulation Questionnaire. Leiderdorp, Netherlands: DATEC; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brown KW, Ryan RM. The benefits of being present: Mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2003;84:822–48. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.84.4.822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24:385–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cohen S, Janicki-Deverts D, Miller GE. Psychological stress and disease. JAMA. 2007;298:1685–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.14.1685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cooper CL, Sloan SJ, Williams S. Occupational Stress Indicator. Windsor: Nfer-Nelson Publishers; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986;51:1173–82. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Panchu P, Ali SL, Thomas T. The interrelationship of personality with stress in medical students. Int J Clin Exp Physiol. 2016;3:134–9. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kabat-Zinn J, Hanh TN. Full Catastrophe Living: Using the Wisdom of Your Body and Mind to Face Stress, Pain, and Illness. New Yark: Random House LLC; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vinothkumar M, Vinu V, Anshya R. Mindfulness, hardiness, perceived stress among engineering and BDS students. Indian J Positive Psychol. 2013;4:514–7. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kabat-Zinn J. New York: Delacorte Press; 1990. Full Catastrophe Living: Using the Wisdom of Your Mind and Body to Face Stress, Pain, and Illness. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shapiro SL, Carlson LE, Astin JA, Freedman B. Mechanisms of mindfulness. J Clin Psychol. 2006;62:373–86. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vidrine JI, Businelle MS, Cinciripini P, Li Y, Marcus MT, Waters AJ, et al. Associations of mindfulness with nicotine dependence, withdrawal, and agency. Subst Abus. 2009;30:318–27. doi: 10.1080/08897070903252973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chiesa A, Serretti A, Jakobsen JC. Mindfulness: Top-down or bottom-up emotion regulation strategy? Clin Psychol Rev. 2013;33:82–96. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2012.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]