Abstract

Background:

Anxiety toward dental treatment can cause people to delay or avoid seeking oral health care despite being in need of treatment. Therefore, recognizing such anxious patients and their appropriate management plays important aspects in clinical practice.

Aim:

The aim of this study was to investigate the level of dental anxiety (DA), factors affecting it, and anxiety toward dental extraction among adults seeking dental care to a dental school in Central India.

Materials and Methods:

The study sample consisted of 1360 consecutive patients aged 18–70 years. Participants completed a questionnaire while in the waiting room, which included the Modified Dental Anxiety Scale (MDAS) to assess the level of DA. An additional item was included which asked participants to rate the anxiety felt on having a tooth extracted.

Results:

Among the study group, 65.1% were men and 34.9% were women. Based on the MDAS score, 41.8% of the participants were identified to be less anxious, 53.2% were moderately or extremely anxious, and 5% were suffering from dental phobia. Female participants and younger patients were more anxious (P = 0.0008). Patients who were anxious had postponed their dental visit (P = 0.0008). Participants who had negative dental experience were more anxious (P = 0.03). Nearly, 83% reported anxiety toward extraction procedure. A significant association was observed between anxiety toward dental extraction and the patients' gender (P = 0.03), age (P = 0.0007), education level (P = 0.03), employment status (P = 0.0006), income (P = 0.0007), self-perceived oral health status (P = 0.03), and their history of visit to dentist (P = 0.02).

Conclusion:

Majority of patients in this population revealed high levels of DA. Factors such as age, gender, education level, occupation, financial stability, and previous bad dental experience influence DA to various levels. Extraction followed by injection of local anesthetics and drilling of tooth provoked more anxiety.

Keywords: Dental anxiety, extraction, Modified Dental Anxiety Scale, phobia

The American Heritage Science Dictionary[1] defines anxiety as “a state of apprehension resulting from the anticipation of a threatening event or situation.” Anxiety and fear, both are distinguished from each other; in that case, the latter occurs in the presence of an observed threat.[2] Dental phobia, a severe dental anxiety (DA), is defined as “marked and persistent fear that is excessive or unreasonable cued by the presence or anticipation of a specific object or situation.”[3] Anxiety toward dental care is a well-known fact and is recognized as a significant factor.[4,5,6,7,8,9,10] Oral and dental health has a significant impact on the quality of life, appearance, and self-esteem of an individual.[11] DA affects a significant proportion of people of all age groups from different socioeconomical classes and remains to be serious concern for both the dentist and the patient for seeking dental health care.[12] The etiology of DA depends on the age of onset; likewise, during childhood, the cause is usually a negative dental experience, and in adulthood, it is more likely due to general anxiety states.[13]

DA can cause a person to delay or avoid seeking dental health care despite being in need of treatment.[14,15] Numerous researchers[16,17,18,19,20] correlated DA and its impact on the oral health-related quality of life and observed that avoidance of treatment by anxious patients is highly associated with a deterioration of their oral health-related quality of life. Therefore, it is necessary to measure the different aspects of DA so that a behavioral intervention could be implemented among such people. Several questionnaires and rating scales have been developed for such purpose. The Corah Dental Anxiety Scale (CDAS) has been used extensively which is simple and consists of four questions. Although it can be scored rapidly, the questions make it difficult to compare the answers. The Modified Dental Anxiety Scale (MDAS), a modified version of the original CDAS, is commonly used to measure anxiety for community-based research and is easy to compare responses.[21,22] The other advantages of the MDAS include its reliability, validity, and ability to be translated into different languages.[23,24,25,26] The MDAS questionnaire also includes a question on dental injections. This scale consists of a series of five questions that are presented to the participants who rate the level of anxiety according to their perception to a particular dental situation. Among the different situations, tooth extraction provokes more anxiety that is perceived as a stressful experience due to physical and psychological impact.[27] Identification of anxious patients seeking dental care can enable the dentist to understand patient's behavior toward treatment and the dentist can implement certain treatment modalities to reduce such anxieties. Nothing is known about DA in the central Indian adults seeking oral and dental health care to a dental school, in particular its prevalence and severity and underlying causes. Such information is valuable while providing a high-quality oral health care. The aim of this study was to measure and evaluate factors influencing DA using the MDAS and its possible causes among adults attending a dental school in Jabalpur city representing central Indian population.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study was conducted at a private Dental School of Rani Durgawati University (RDU) from March 2015 to December 2015. Approval for the study was obtained from the Ethical Committee of RDU. The consecutive patients attending the outpatient department for dental treatment were provided with questionnaire and were asked to complete it while in the waiting area. The only participants who were native of Madhya Pradesh with Hindi as their mother tongue were recruited to participate in the survey. The patients undergoing psychiatric therapy or suffering from generalized anxiety disorders and completely edentulous patients were excluded from the study. The aims and objectives of the study were explained to each patient, and informed consent was obtained from those who agreed for participation. The participants were requested to fill a history form to receive information about age, gender, educational qualification, occupation, income, history of previous dental visit and duration since the last visit to dentist, previous dental experience, self-perceived oral health status, and postponement of dental treatment due to DA. To assess their level of anxiety, the participants were asked to complete the MDAS administered in Hindi. In addition to the MDAS, a question on anxiety toward dental extraction was included in the questionnaire as follows: “How anxious would you feel if you were about to have your tooth/teeth extracted?” and the patients were asked to choose the answer from Likert scale responses such as “not anxious, slightly anxious, fairly anxious, very anxious, or extremely anxious.”

Survey questionnaire

The MDAS questionnaire was adapted from previous studies used in Indian populations.[24,28] The reliability and validity was established in these previously published research works. The questionnaire was translated into Hindi which was done according to forward and backward blind translation process. The back translated versions were reviewed by the authors, and the translated version was corrected along with the translators to eliminate any difference in the meaning between original version and back translated versions. The final back translated version was pretested on the target Hindi-speaking population. Final corrections were made to the translated Hindi version.

Statistical analysis

Data were entered and analyzed using a computer database/statistical software package (SPSS) version 21 (SPSS Inc. Chicago, USA). Mean total MDAS score was calculated for all the categorized variables. Independent sample t-test and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) were done to compare mean total MDAS score between categories in a group. Spearman rank correlation was done to assess the strength of association between MDAS and anxiety toward extraction. Chi-square test was used to evaluate the association between anxiety toward extraction and the variables. Statistical significance was defined at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

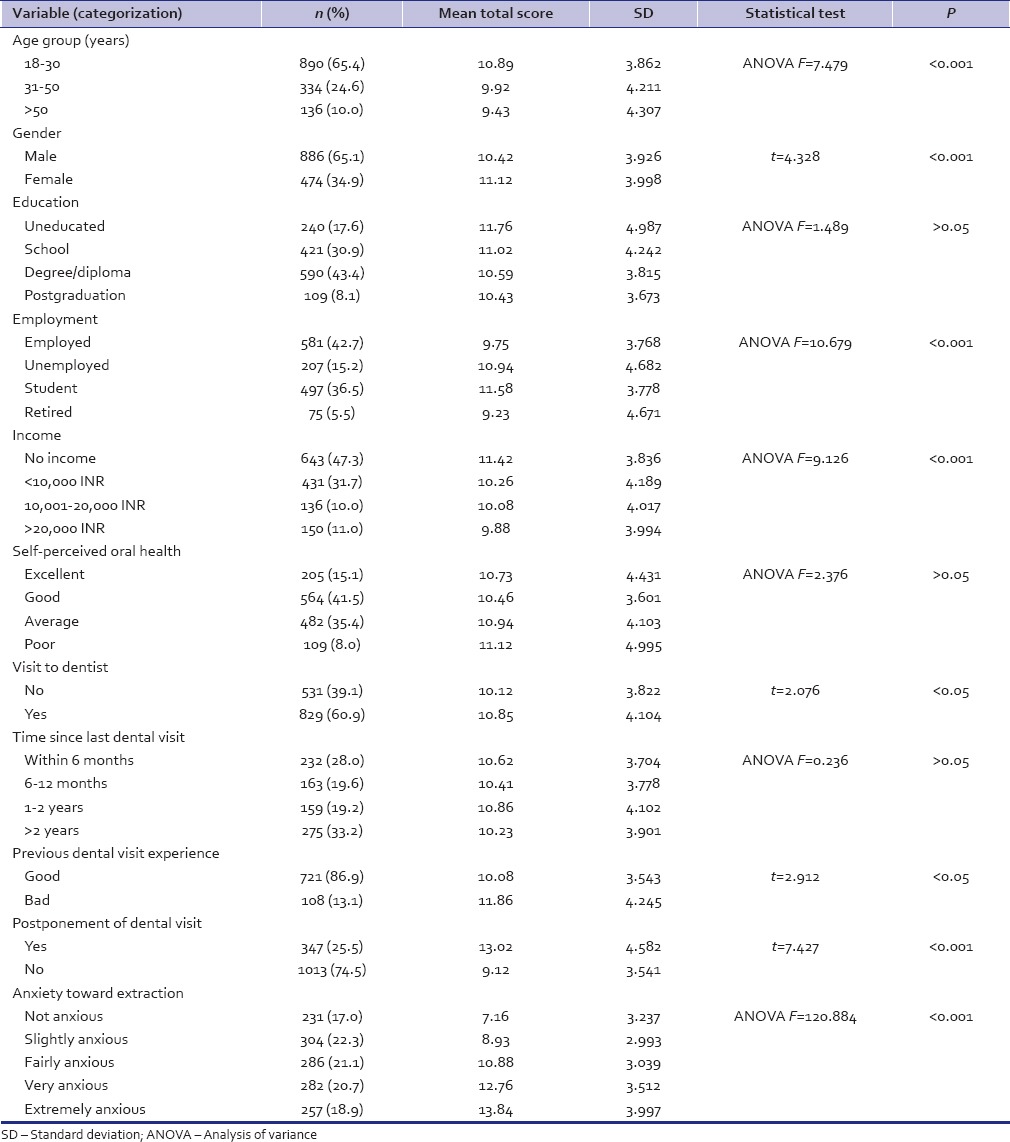

Table 1 summarizes the descriptive statistics and the factors influencing anxiety, with the relevant statistical test - ANOVA, t-test, and P values. Mean total score for DA on the MDAS was 11.1 (standard deviation [SD] = 3.98). Based on the MDAS score, 41.2% of the patients were identified to be less anxious (5–9 of total score) and 53.2% were moderately anxious (10–18 of total score). The patients with total score 19 or above (5%) were identified as extremely anxious or dental phobic.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics, mean total score in the Modified Dental Anxiety Scale, and statistical test (n=1360)

Age brackets and gender of the respondents

The study sample was divided into three age brackets. Among the 1360 respondents, majority (65.4%) belonged to age bracket of 18–30 years, 24.6% belonged to 31–50 years of age bracket, and only 10% belonged to >50 years of age bracket. The mean anxiety scores were 10.89, 9.92, and 9.43, respectively, among the divided groups. Mean age of the respondents was 28.2 years (SD = 11.92). One-way ANOVA showed a significant difference between the age brackets in relation to their mean MDAS scores and it decreased with increasing age. Younger patients were more anxious (P = 0.0008), whereas other groups demonstrated a comparable mean MDAS scores. Nearly, 65.1% of the respondents were males and 34.9% were females. When an independent t-test was applied, female respondents were found to be more anxious than their male counterparts (P = 0.0008).

Education level of the respondents

Majority of patients (43.4%) were graduated, 30.9% completed their school education, and 8.1% were postgraduated academically. Nearly, 17.6% of the respondents were uneducated. Uneducated participants were more anxious toward dental procedures than the educated patients. The mean MDAS score for uneducated group was 11.76, whereas, for those who completed their education in school, degree or diploma, and postgraduation, it was 11.02, 10.59, and 10.43, respectively. As the educational qualification of the participants increased from school to postgraduation, the anxiety score showed a gradual decrease. However, one-way ANOVA showed no significant difference in the anxiety score based on the level of education (P = 0.695).

Employment and income of the respondents

On the basis of their employment, the patients were divided into employed, unemployed, student, and retired groups. The mean MDAS scores for these groups were 9.75, 10.94, 11.58, and 9.23, respectively. Unemployed and student respondents reported more DA compared to employed group. Retired participants were dentally less anxious than the younger counterparts. One-way ANOVA showed a significant difference in the mean anxiety score based on the employment of the participants (P = 0.0006). On the basis of monthly income, the participants were divided into those without income, <10,000 INR, 10,001–20,000 INR, and >20,000 INR, which showed mean anxiety scores of 11.42, 10.26, 10.08, and 9.88, respectively. Evaluation of economic status with anxiety level showed that respondents who had no income were more anxious dentally than those who were financially independent. One-way ANOVA showed a highly significant difference in the anxiety score based on respondent's monthly income (P = 0.0007).

Self-perceived oral health of the respondents

According to respondents' self-perceived oral health status, they were divided into excellent, good, average, and poor oral health groups. The mean anxiety scores in these groups were 10.73, 10.46, 10.94, and 11.12, respectively. Majority of the participants (41.5%) perceived their oral health status as good. Nearly, 8% of patients perceived their oral health as poor and were found to be more anxious toward the dental procedures. However, one-way ANOVA showed no significant difference in the anxiety score based on the level of patient's self-perceived oral health status (P = 0.728).

Respondents' visit to the dentist and their previous dental experience

About 60.9% of patients had visited a dentist once before and 39.1% of patients had never visited the dentist ever before. The mean anxiety score among those who visited the dentist was 10.85. When an independent t-test was applied, those respondents who had a visit to a dentist were found to be more anxious than those who never visited a dentist (P < 0.05). The participants who had visited the dentist more than 1–2 years back showed increased anxiety score toward dental procedures. However, one-way ANOVA showed no significant difference in the anxiety score based on the time since respondent's last dental visit (P = 0.620). Majority of patients (86.9%) reported that they had a good experience of their previous dental visit. The patients who reported having bad experience toward their previous dental visit were more anxious than those who had good dental experience. Independent t-test demonstrated a high significant difference in the anxiety score with respect to respondents' experience during their previous dental visit (P = 0.02).

Postponement of dental visit and anxiety toward dental extraction

Majority of patients (74.5%) did not postpone their dental visit, while 25.5% postponed their visit to a dental clinic. The mean anxiety scores were 13.02 and 9.12, respectively, of the divided groups. Independent t-test showed a significant difference in the mean anxiety score between respondents with respect to their postponement of dental visit (P = 0.0006). It was clear that extremely anxious patients had postponed their visit to a dental clinic.

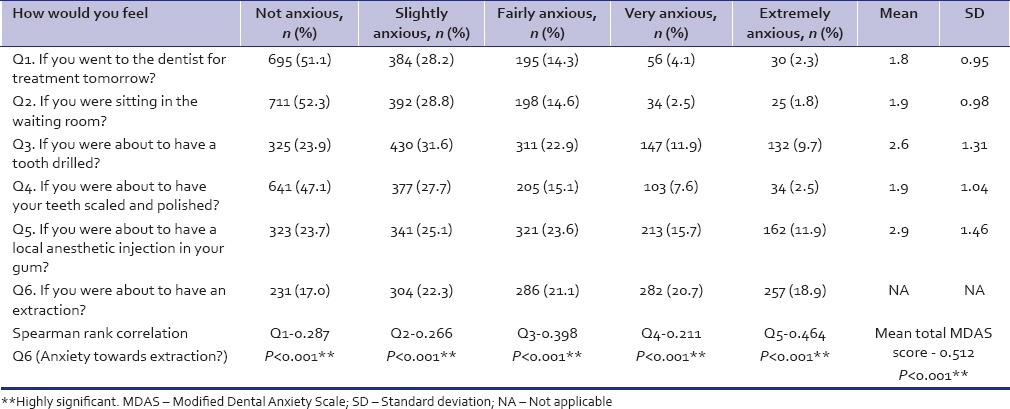

The mean and SD of the six anxiety-provoking stimuli and correlation between anxiety toward dental extraction and MDAS scale are summarized in Table 2. When the six anxiety-provoking stimuli were evaluated on the MDAS, it was observed that 51.1% of the patients were not anxious about their dental visit, 52.3% felt that they would not be anxious while sitting in the waiting room for their appointment, 78.7% felt that getting their tooth drilled would make them anxious, 53% agreed that scaling and polishing would make them anxious, and 11.9% felt that they would be extremely anxious if they have to receive injection in their mouth. On assessment of extraction as an anxiety-provoking stimulus, it was seen that majority of the participants, that is, 83% reported anxiety, and among them, 18.9% felt that they would be extremely anxious if they have to extract their tooth. The correlation analysis (Spearman rank correlation) between the MDAS and anxiety toward dental extraction revealed a high significance (P = 0.0004).

Table 2.

Participants’ response to each question of the Modified Dental Anxiety Scale and correlation between anxiety toward extraction and the Modified Dental Anxiety Scale (n=1360)

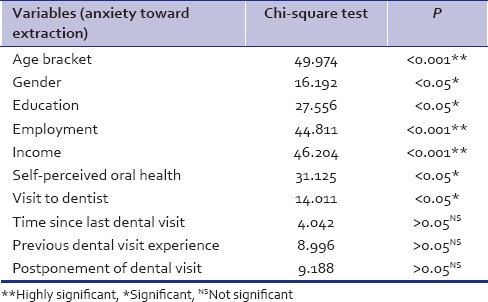

Table 3 demonstrates the association between anxiety toward dental extraction and the variables analyzed using Chi-square test. The different variables, such as age bracket (P < 0.001), gender (P = 0.03), education level (P = 0.03), employment status (P = 0.0006), monthly income (P = 0.0007), self-perceived oral health (P = 0.03), and visit to dentist (P = 0.02), were significantly associated with anxiety toward dental extraction. Analysis showed that increased anxiety for dental extraction was associated with higher mean total MDAS score.

Table 3.

Association between anxiety toward extraction and the variables analyzed using Chi-square test

DISCUSSION

The MDAS asks the patients to score their level of anxiety with respect to five dental situations using a 5-point scale. The MDAS was used in this investigation to investigate the patient's anxiety level toward specific dental procedures, and also, one question was added to assess their anxiety toward dental extraction. In India, different states such as Gujarat, Haryana, Rajasthan, and Tamil Nadu have indicated a higher prevalence of DA among the Indian patients seeking oral care to a dental clinic.[28,29,30,31,32] This study was carried out in Jabalpur district, Madhya Pradesh, which represents central Indian population. The results of this study agree with the similar studies conducted in other states of the country. However, the findings show a higher prevalence of DA when compared with that of Western countries.[10,11,12] This evidence could be attributed to country's multiple diversities with different customs, cultures, and superstitious beliefs toward dental treatment. Lack of oral health awareness and views from members of the family could be other contributing factors. In India, any unpleasant dental experience with a single member of the family influences other member's attitude toward dental treatment. Among the studied participants, only 5% showed dental phobia which was almost similar to the findings of other studies.[11,13,14] However, this finding of dental phobic patients was lesser compared to other studies conducted in several industrialized countries.[4,5,15] Many “dentally phobic” individuals do not see their fear as being “excessive” or “unreasonable” because they base their fear on past dental experiences that were highly traumatizing. Dental phobia may be more common with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).[33] PTSD is a delayed and protracted response to a stressful event of an exceptionally threatening nature which may cause distress in almost everyone.[34] It is possible for patients to develop both a PTSD and a phobia following a traumatic dental experience.

The findings in this central Indian sample are also consistent with those of other studies reporting that females generally demonstrate higher levels of DA than their male counterparts.[10,11,14,16,35,36,37] Females in this study appear to have greater anxiety in anticipation of dental treatment. This could be attributed to the truth that females usually admit their fears readily than males and possess lower tolerance to pain. However, the results of this study are in contrast to other studies who reported no difference in the anxiety level between males and females due to cultural differences.[30,32,38,39] The results from this study showed that the mean anxiety score reduced with increasing age which is in agreement with the studies of McGrath and Bedi,[11] Ng and Leung,[16] Acharya,[17] Yuan et al.,[26] Appukuttan et al.,[29] Appukuttan et al.,[32] and Settineri et al.[40] Younger patients were more anxious compared to their elder counterparts. However, several other studies[23,39,41] contradicted this trend occurring widely among younger patients. Locker and Liddell[4] correlated this reduction in anxiety with age to age-dependent cerebral deterioration, extinction or habituation, increased ability to cope with experience, and more exposure to systemic diseases and treatment.

The uneducated, unemployed, and financially dependents showed higher anxiety scores which was in agreement with Malvania and Ajithkrishnan[28] and Appukuttan et al.[29] This could be attributed to the ability of educated people to cope better and rationalize a situation rather than avoiding it. Furthermore, the factors such as lower socioeconomic status, poor physical health, depression, and less access to health care may contribute largely in developing higher anxiety in anticipation to dental treatment.[28] However, few studies have not found such a relationship.[4] The participants who rated their oral health as poor had higher levels of DA than those participants who rated their oral health as excellent, good, and average. This finding was in accordance with the findings of Locker and Liddell,[4] Appukuttan et al.,[29] Appukuttan et al.,[32] and Doerr et al.[42]

Participants with anxiety and those with past negative dental experience showed postponing their appointments to dentist. This finding was in accordance with the previous findings.[30,43,44,45,46] Among the participants who visited the dentist previously, those who had a negative dental experience reported higher level of anxiety which was in agreement with the studies carried out by Moore et al.,[9] Appukuttan et al.,[29] Appukuttan et al.,[32] and Acharya.[44] Those patients with higher level of anxiety made their last visit to dentist 2 years back, which was in accordance to the previous findings.[29,32,47,48] In the present study, the addition of the question on anxiety toward dental extraction showed that, among this sample of central Indian adults, the anxiety felt for this procedure is comparatively higher to that felt in anticipation to injecting local anesthetics or drilling a tooth for restoration. Past negative experiences appear to have influenced the level of anxiety toward dental procedure in this population.

Brukiene et al.[49] in their cross-sectional study in Lithuanian adults found that patients with no past invasive dental treatment were less anxious than those who had past negative experience. Ekanayake and Dharmawardena[35] reported that Sri Lankan adults who had an extraction at the last dental visit were significantly more anxious than those who had restorative care. Oosterink et al.[50] studied anxiety-provoking capacity of 67 stimuli characteristics of the dental setting and reported that “invasive” surgical procedures were rated as the most anxiety provoking compared to “noninvasive” dental procedures that were rated as the least anxiety provoking. Rodríguez Vázquez et al.[27] assessed the stress among Spanish population seeking primary dental care and found that 10% of 804 patients experienced high level of stress before undergoing dental extraction. Naidu and Lalwah[51] investigated a sample of adult West Indians and observed that half of the participants were extremely anxious for drilling of tooth, local anesthetic injections, and tooth extraction. Liau et al.[52] reported that high anxiety, younger age, and traumatic dental history were correlated with increased heart rate while injecting local anesthetics for tooth extraction. In their study, majority of patients (82.6%) were anxious toward dental extraction which was in agreement with several studies.[29,32,41,51]

More than a half of the participants in this study showed moderate anxiety levels toward dental treatment implying that DA may be a significant problem in this population. Incorporation of anxiety-provoking capacity of dental procedures such as drilling of a tooth and injection of local anesthetics in MDAS may not be as sensitive in establishing anxiety levels in all situations, particularly in some developing countries such as India. The contributing factors for this may be less accessibility to oral health care due to low dentist-to-population ratio, geographic location, and affordability toward treatment.[53] Extraction of decayed or painful teeth may, therefore, be the more common mode of treatment rather than restoring it, which may be the situation in Jabalpur district where approximately 272 dentists serve 1.3 million people, with more registered dentists practicing in urban areas of the district. Public health centers provide free treatment, but these health cares are poorly equipped and understaffed. Therefore, dental extractions become the most common form of oral care for adults. Furthermore, some dentistry in Jabalpur are undertaken by unqualified dentists or dental quacks whose training and skill would be questionable but yet appear to be popular among people from lower socioeconomic status. Majority of adult patients opt for dental extractions as compared to restorative care among this population. Therefore, the addition of a question on extraction showed that these anxiety-provoking stimuli invoked almost similar levels of anxiety. This study had a few limitations in terms of the method chosen for sampling. As it was a dental school, the majority of patients were of low social strata and little educational background. Hence, exclusion of patients from other social strata may lead to underrepresentation of the general population. Another limitation was that a very few anxiety-provoking stimuli were assessed in this study. However, the available data help to assess the perceptions of the majority of the central Indian population. The data should, therefore, be interpreted with extreme caution so as to minimize the levels of anxiety among adolescents toward dental procedures. The information attained through this investigation can be used as baseline data for policymaking, and innovative preventive programs can be initiated and established.

CONCLUSION

DA is a public health problem as it affects not only the individual, but also the community as a whole. In this studied population, DA was highly prevalent; moreover, among the anxiety-provoking stimuli assessed, it was clear that extraction of tooth provoked more anxiety followed by injection of local anesthetics and drilling of tooth. This finding could be of great help to practicing dentists and researchers in the implementation of better patient management strategies by creating awareness and educating society and policymaking.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.American Heritage Science Dictionary. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ohman A. Fear and anxiety, evolutionary, cognitive and clinical perceptions. In: Lewis M, Haviland JM, editors. Handbook of Emotions. New York: The Gulliford Press; 2000. pp. 573–93. [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders DSM-IV. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Locker D, Liddell AM. Correlates of dental anxiety among older adults. J Dent Res. 1991;70:198–203. doi: 10.1177/00220345910700030801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Teo CS, Foong W, Lui HH, Vignehsa H, Elliott J, Milgrom P. Prevalence of dental fear in young adult Singaporeans. Int Dent J. 1990;40:37–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hakeberg M, Berggren U, Carlsson SG. Prevalence of dental anxiety in an adult population in a major urban area in Sweden. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1992;20:97–101. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1992.tb00686.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stouthard ME, Hoogstraten J. Prevalence of dental anxiety in The Netherlands. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1990;18:139–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1990.tb00039.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klingberg G. Dental fear and behaviour management problems in children. A study of measurement, prevalence, concomitant factors and clinical effects. Swedish Dent J. 1995;103:1–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moore R, Birn H, Kirkegaard E, Brødsgaard I, Scheutz F. Prevalence and characteristics of dental anxiety in Danish adults. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1993;21:292–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1993.tb00777.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peretz B, Efrat J. Dental anxiety among young adolescent patients in Israel. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2000;10:126–32. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-263x.2000.00181.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McGrath C, Bedi R. The association between dental anxiety and oral health-related quality of life in Britain. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2004;32:67–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2004.00119.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eitner S, Wichmann M, Paulsen A, Holst S. Dental anxiety – An epidemiological study on its clinical correlation and effects on oral health. J Oral Rehabil. 2006;33:588–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2842.2005.01589.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Locker D, Liddell A, Dempster L, Shapiro D. Age of onset of dental anxiety. J Dent Res. 1999;78:790–6. doi: 10.1177/00220345990780031201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pohjola V, Lahti S, Vehkalahti MM, Tolvanen M, Hausen H. Association between dental fear and dental attendance among adults in Finland. Acta Odontol Scand. 2007;65:224–30. doi: 10.1080/00016350701373558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eli I. Behavioural interventions could reduce dental anxiety and improve dental attendance in adults. Evid Based Dent. 2005;6:46. doi: 10.1038/sj.ebd.6400323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ng SK, Leung WK. A community study on the relationship of dental anxiety with oral health status and oral health-related quality of life. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2008;36:347–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2007.00412.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Acharya S. Oral health-related quality of life and its associated factors in an Indian adult population. Oral Health Prev Dent. 2008;6:175–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Locker D, Liddell A, Burman D. Dental fear and anxiety in an older adult population. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1991;19:120–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1991.tb00125.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hollister MC, Weintraub JA. The association of oral status with systemic health, quality of life, and economic productivity. J Dent Educ. 1993;57:901–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mehrstedt M, John MT, Tönnies S, Micheelis W. Oral health-related quality of life in patients with dental anxiety. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2007;35:357–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2007.00376.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Corah NL, Gale EN, Illig SJ. Assessment of a dental anxiety scale. J Am Dent Assoc. 1978;97:816–9. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1978.0394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Humphris GM, Morrison T, Lindsay SJ. The Modified Dental Anxiety Scale: Validation and United Kingdom norms. Community Dent Health. 1995;12:143–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tunc EP, Firat D, Onur OD, Sar V. Reliability and validity of the modified dental anxiety scale (MDAS) in a Turkish population. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2005;33:357–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2005.00229.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Appukuttan D, Datchnamurthy M, Deborah SP, Hirudayaraj GJ, Tadepalli A, Victor DJ. Reliability and validity of the Tamil version of modified dental anxiety scale. J Oral Sci. 2012;54:313–20. doi: 10.2334/josnusd.54.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Coolidge T, Arapostathis KN, Emmanouil D, Dabarakis N, Patrikiou A, Economides N, et al. Psychometric properties of Greek versions of the modified Corah dental anxiety scale (MDAS) and the Dental Fear Survey (DFS) BMC Oral Health. 2008;8:29. doi: 10.1186/1472-6831-8-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yuan S, Freeman R, Lahti S, Lloyd-Williams F, Humphris G. Some psychometric properties of the Chinese version of the modified dental anxiety scale with cross validation. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2008;6:22. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-6-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rodríguez Vázquez LM, Rubiños López E, Varela Centelles A, Blanco Otero AI, Varela Otero F, Varela Centelles P. Stress amongst primary dental care patients. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2008;13:E253–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Malvania EA, Ajithkrishnan CG. Prevalence and socio-demographic correlates of dental anxiety among a group of adult patients attending a dental institution in Vadodara city, Gujarat, India. Indian J Dent Res. 2011;22:179–80. doi: 10.4103/0970-9290.79989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Appukuttan D, Subramanian S, Tadepalli A, Damodaran LK. Dental anxiety among adults: An epidemiological study in South India. N Am J Med Sci. 2015;7:13–8. doi: 10.4103/1947-2714.150082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kumar S, Bhargav P, Patel A, Bhati M, Balasubramanyam G, Duraiswamy P, et al. Does dental anxiety influence oral health-related quality of life. Observations from a cross-sectional study among adults in Udaipur district, India? J Oral Sci. 2009;51:245–54. doi: 10.2334/josnusd.51.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marya CM, Grover S, Jnaneshwar A, Pruthi N. Dental anxiety among patients visiting a dental institute in Faridabad, India. West Indian Med J. 2012;61:187–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Appukuttan DP, Tadepalli A, Cholan PK, Subramanian S, Vinayagavel M. Prevalence of dental anxiety among patients attending a dental educational institution in Chennai, India – A questionnaire based study. Oral Health Dent Manag. 2013;12:289–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bracha HS, Vega EM, Vega CB. Posttraumatic dental-care anxiety (PTDA): Is “dental phobia” a misnomer? Hawaii Dent J. 2006;37:17–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lloyd GG, Sharpev MC. Medical psychiatry. In: Haslett C, Chilvers ER, Boon NA, Colledge NR, editors. Davidson's Principles and Practice of Medicine. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 2002. pp. 245–69. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ekanayake L, Dharmawardena D. Dental anxiety in patients seeking care at the University Dental Hospital in Sri Lanka. Community Dent Health. 2003;20:112–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Quteish Taani DS. Dental anxiety and regularity of dental attendance in younger adults. J Oral Rehabil. 2002;29:604–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2842.2002.00905.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Erten H, Akarslan ZZ, Bodrumlu E. Dental fear and anxiety levels of patients attending a dental clinic. Quintessence Int. 2006;37:304–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Economou GC. Dental anxiety and personality: Investigating the relationship between dental anxiety and self-consciousness. J Dent Educ. 2003;67:970–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thomson WM, Locker D, Poulton R. Incidence of dental anxiety in young adults in relation to dental treatment experience. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2000;28:289–94. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0528.2000.280407.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Settineri S, Tati F, Fanara G. Gender differences in dental anxiety: Is the chair position important? J Contemp Dent Pract. 2005;6:115–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nair MA, Shankarapillai R, Chouhan V. The dental anxiety levels associated with surgical extraction of tooth. Int J Dent Clin. 2009;1:20–3. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Doerr PA, Lang WP, Nyquist LV, Ronis DL. Factors associated with dental anxiety. J Am Dent Assoc. 1998;129:1111–9. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1998.0386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nicolas E, Collado V, Faulks D, Bullier B, Hennequin M. A national cross-sectional survey of dental anxiety in the French adult population. BMC Oral Health. 2007;7:12. doi: 10.1186/1472-6831-7-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Acharya S. Factors affecting dental anxiety and beliefs in an Indian population. J Oral Rehabil. 2008;35:259–67. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2842.2007.01777.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Skaret E, Raadal M, Berg E, Kvale G. Dental anxiety and dental avoidance among 12 to 18 year olds in Norway. Eur J Oral Sci. 1999;107:422–8. doi: 10.1046/j.0909-8836.1999.eos107602.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hägglin C, Hakeberg M, Ahlqwist M, Sullivan M, Berggren U. Factors associated with dental anxiety and attendance in middle-aged and elderly women. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2000;28:451–60. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0528.2000.028006451.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Thomson WM, Stewart JF, Carter KD, Spencer AJ. Dental anxiety among Australians. Int Dent J. 1996;46:320–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Armfield JM, Stewart JF, Spencer AJ. The vicious cycle of dental fear: Exploring the interplay between oral health, service utilization and dental fear. BMC Oral Health. 2007;7:1. doi: 10.1186/1472-6831-7-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Brukiene V, Aleksejuniene J, Balciuniene I. Is dental treatment experience related to dental anxiety. A cross-sectional study in Lithuanian adolescents? Stomatologija. 2006;8:108–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Oosterink FM, de Jongh A, Aartman IH. What are people afraid of during dental treatment. Anxiety-provoking capacity of 67 stimuli characteristic of the dental setting? Eur J Oral Sci. 2008;116:44–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.2007.00500.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Naidu RS, Lalwah S. Dental anxiety in a sample of West Indian adults. West Indian Med J. 2010;59:567–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Liau FL, Kok SH, Lee JJ, Kuo RC, Hwang CR, Yang PJ, et al. Cardiovascular influence of dental anxiety during local anesthesia for tooth extraction. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2008;105:16–26. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2007.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hobdell MH, Sheiham A. Barriers to the promotion of dental health in developing countries. Soc Sci Med A. 1981;15:817–23. doi: 10.1016/0271-7123(81)90026-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]