Abstract

ANT1 is one of the nuclear genes responsible of autosomal dominant progressive external ophthalmoplegia (adPEO) with mitochondrial DNA multiple deletions. The course of ANT1- related adPEO is relatively benign, symptoms being generally restricted to skeletal muscle.

Here we report the case of an Italian 74 years old woman with ANT1-related adPEO and dementia.

Further studies are needed to assess the prevalence of central neurological manifestations in ANT1 mitochondrial disease.

Key words: mitochondrial disease, adPEO, ANT1, cognitive impairment, mitochondrial dementia

Introduction

ANT1, encoded by the SLC25A4 gene, is a member of a family of integral membrane transport molecules widely expressed in the inner mitochondrial membrane. ANT1 forms a channel which moves ADP into the mitochondrion and ATP out of the mitochondrion to be used as energy for the cell. This protein seems also to be a component of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore, the formation of which appears to be an important step of apoptosis. ANT1 is highly expressed in heart and skeletal muscle, but also in the brain (1, 2). SLC25A4 gene mutation can be responsible of three main phenotype: autosomal dominant progressive external ophthalmoplegia (adPEO) with mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) multiple deletions, first described in 2000 (3); Autosomal Dominant Mitochondrial DNA Depletion Syndrome 12A (4) characterized by hypotonia, hypertrophyc cardiomyophaty and pulmonary involvement; Autosomal Recessive Mitochondrial DNA Depletion Syndrome 12B described later in the text (5).

The course of ANT1-related adPEO is relatively benign, symptoms being generally restricted to skeletal muscle. This is explained by the observation that ANT1 is the main isoform of the ADP/ATP carrier in skeletal muscle mitochondria (1, 2). Afterwards, Palmieri et al. described a 368C-A transversion homozygous mutation of ANT1 gene associated with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, mild myopathy with exercise intolerance and lactic acidosis, but no ophthalmoplegia (5). Despite a well-established knowledge of this metabolic dysfunction in skeletal muscle, other aspects of adPEO caused by ANT1 mutation are less known. In particular, there are no data showing an association between ANT1 mutation and cognitive impairment. Here we describe a case of cognitive impairment in a woman harboring a mutation in SLC25A4 gene.

Case report

A 74 years old Italian woman arrived to our attention complaining about a ten years history of eyelid ptosis. The patient also presented weakness and fatigue. Patient's parents were not consanguineous. She had family history of eyelid ptosis (mother, maternal grandmother, maternal aunt), ischaemic heart disease (mother and brother), and sudden death (father). Her personal history was significant for autoimmune thyroid disease and heart palpitations. She underwent echocardiography revealing hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with mild diastolic dysfunction. Neurological examination showed bilateral eyelid ptosis, ophtalmoplegia and mild weakness of lower limbs (MRC 4/5). Blood tests, including lactate, were normal. Electromyography showed a myopathic pattern. MtDNA and POLG analyses were negative. Sequencing of the SLC25A4 gene revealed the heterozygous mutations (c.340G > C) in the exon 2, resulting in an Ala114- to-Pro (A114P) substitution, previously described in five families with PEO (3). At age 75, the patient started to report disorders of short-term memory; the neuropsychological evaluation demonstrated a mild impairment of verbal memory and the attentive functions.

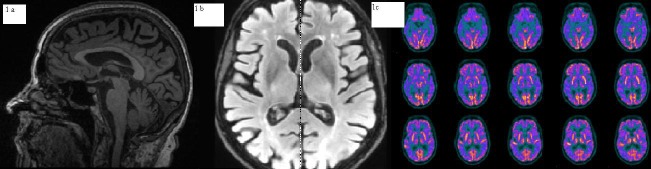

Magnetic resonance of brain revealed widespread moderate cortical atrophy and mild leukoaraiosis.

(Figs. 1a,1b). Magnetic resonance spectroscopy of brain showed mild elevation of lactate in posterior intermispheric region and in ventricular region. The brain fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (PET) revealed bilaterally reduced metabolism in the temporal poles, lateral temporal and posterior parietal areas (Fig. 1c). Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) sample was obtained by lumbar puncture and concentrations of βeta amyloid protein (Aβ1-42), tau protein (Ttau) and phosphorylate tau protein (P-tau) were determined. Aβ1-42 was slightly reduced (575 pg/mL -normal values > 600), T-tau was increased (1131 pg/ml - v.n. < 275) as well as P-tau (141 pg/ml, n.v. < 60), whereas lactate was 14 md\dl. Apolipoprotein E genotype was E3E3.

Figure 1.

1a and 1b Brain MRI demonstrates cortical atrophy. 1c positron emission tomography (PET) revealed bilaterally reduced metabolism in the temporal poles, lateral temporal and posterior parietal areas.

Discussion

Dementia is a chronic condition characterized by a gradual decrease in the ability to remember, associated with a decrease of other cognitive functions which it translates into a reduced ability to judge or to reflect; interfering with activities of daily living (6). Cognitive domains affected include memory, language, orientation, constructional abilities, abstract thinking, problem solving, or praxis. Most evident is impairment in learning new information (6). Mitochondrial diseases are multisystem disorders that also affect central nervous system. One of the clinical features of these diseases is the so called "mitochondrial dementia" which is often characterized by specific cognitive deficits, particularly in abstract reasoning, verbal and visual memory, language (naming and fluency), executive or constructive functions, calculation, attention (attention deficit disorder and decreased attention span), or visuo-spatial function (7-9). It's not well defined the role of mitochondrial dysfunction in the development of cognitive impairment (10). The differential diagnosis of mitochondrial dementia and symptomatic dementia is critical and the timing of mitochondrial disease diagnosis is important because the onset of cognitive dysfunction as only or first symptoms of mitochondrial disease is rare; vice versa, if a patient develops mitochondrial phenotype before the development of dementia, the cognitive involvement can be more easily suspected as mitochondrial dementia. Other important elements that can orient towards a diagnosis of mitochondrial dementia are the elevation of lactate at cerebrospinal fluid and\or a peak of lactate at magnetic resonance spectroscopy.

ANT1 mutations commonly lead to a "pure PEO", characterized by eyelid ptosis, ophthalmoplegia and mild muscle symptoms. This is because ANT1 is mainly expressed in the mitochondria of skeletal muscle tissue and heart (2). Nevertheless, ANT1 expression is not skeletal muscle-restricted, and a low expression is present also in the brain. While few literature data reported an association between ANT1 mutation and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (5), the link between ANT1 mutation and cognitive impairment is a new finding.

We are aware that the association of adPEO and cognitive dysfunction observed in our patient may be a casual coincidence. However, previous literature data support our hypothesis of mitochondrial dementia (11). Features that arguments in favor of mitochondrial dementia are the presence of a mild lactate peak in brain spectroscopy, the diffuse cortical atrophy associated with mild leukoaraiosis, the timing of mitochondrial disease progression (PEO onset before cognitive impairment), and the reduced metabolism in PET whit a pattern non typical of Alzheimer disease. Moreover, the Aβ1-42 values in our patient are only mildly decreased, differently on what we commonly see in Alzheimer disease and are more similar to what we observe in normal aging (12). Conversely, the dosage of T-tau and P-tau in the patient CSF is not strongly indicative of mitochondrial dementia. Taken together, the above-mentioned findings suggest that in some patients with ANT1 mutation, a multisystem involvement may be observed, including cognitive impairment. Further studies in large groups of ANT1 patients are needed in order to assess the prevalence of CNS involvement in ANT1 patients and to better characterize the clinical heterogeneity (if any) of this genotype.

Acknowledgements

This work was partially supported by Telethon grant GUP09004 and Telethon-Mitocon grant GSP16001.

References

- 1.Klingenberg M. The ADP and ATP transport in mitochondria and its carrier. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1778:1978–2021. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2008.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stepien G, Torroni A, Chung AB, et al. Differential expression of adenine nucleotide translocator isoforms in mammalian tissues and during muscle cell differentiation. Biol Chem. 1992;267:14592–14597. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaukonen J, Juselius JK, Tiranti V, et al. Role of adenine nucleotide translocator 1 in mtDNA maintenance. Science. 2000;289:782–785. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5480.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thompson K, Majd H, Dallabona C, et al. Recurrent de novo dominant mutations in SLC25A4 cause severe early-onset mitochondrial disease and loss of mitochondrial DNA copy number. Am J Hum Genet. 2016;99:860–876. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2016.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Palmieri L, Alberio S, Pisano I, et al. Complete loss-of-function of the heart/muscle-specific adenine nucleotide translocator is associated with mitochondrial myopathy and cardiomyopathy. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:3079–3088. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Corey-Bloom J, Thal LJ, Galasko D, et al. Diagnosis and evaluation of dementia. Neurology. 1995;45:211–218. doi: 10.1212/wnl.45.2.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaufmann P, Shungu DC, Sano MC, et al. Cerebral lactic acidosis correlates with neurological impairment in MELAS. Neurology. 2004;62:1297–1302. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000120557.83907.a8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sartor H, Loose R, Tucha O, et al. MELAS: a neuropsychological and radiological follow-up study. Mitochondrial encephalomyopathy, lactic acidosis and stroke. Acta Neurol Scand. 2002;106:309–313. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0404.2002.01089.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dickerson BC, Holtzman D, Grant PE, et al. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Case 36-2005. A 61-year-old woman with seizure, disturbed gait, and altered mental status. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2271–2280. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcpc059032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Finsterer J. Cognitive disfunction in mitochondrial disorders. Acta Neurol Scand. 2012;126:1–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2012.01649.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Finsterer J. Mitochondrial disorders, cognitive impairment and dementia. J Neurol Sci. 2009:143–148. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2009.02.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blennow K, Mattsson N, Schöll M, et al. Amyloid biomarkers in Alzheimer's disease. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2015;36:297–309. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2015.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]