Abstract

In patients with muscular dystrophies both muscle length tension relationship changes and muscle elasticity and plasticity are decreased, resulting in impaired inspiratory muscle function and decreased vital capacity. Furthermore, the loss of deep breathing further increases the risk of alveolar collapse, hypoventilation and atelectasias. In this case report, a stable improvement of vital capacity after treatment with mounthpiece ventilation (MPV), was observed, suggesting that not invasive ventilation (NIV) might help to maintai lung and chest wall compliance, prevent hypoventilation and atelectasias which in turn may slow down the development of the restrictive respiratory pattern. The improvement of vital capacity may have a positive impact on alveolar ventilation by reducing the time with SaO2 values below 90%. This case illustrates that MPV is an effective method to improve respiratory function in patients non-tolerant of nasal mask and a valid alternative option for those who need NIV support for the most part of the day. Furthermore, the use of MPV, alone or combined with other interfaces, improves the quality of life of the neuromuscular patients and promotes a greater adherence to mechanical ventilation.

Key words: Steinert disease, lung function, not invasive nasal ventilation, mounthpiece ventilation

Introduction

Type 1 myotonic dystrophy or Steinert's disease is a progressive multisystem disorder mainly, characterized by myotonia, muscular dystrophy, cataracts, hypogonadism, frontal balding, and cardiac and respiratory involvement (1-5). The disease results in progressive weakness and wasting of respiratory muscles. Many patients develop sleep disorders and respiratory failure, and often need noninvasive mechanical ventilation. Sometimes patients refuse the noninvasive mechanical ventilation due to excessive air leakage, claustrophobia, and anxiety of being unable to communicate with family members.

Case description

A 44-year-old woman with Steinert disease was referred to our hospital for evaluation with complaints of daytime fatigue and headaches. The symptoms were assessed with a Epworth sleepiness scale questionnaire. Forced vital capacity (FVC) and forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) were measured with a hand held spirometer. Arterial blood gas tension was determined from arterialized ear lobe blood in automated blood gas analyzer. Overnight polysomnography was also performed.

The pulmonary function test revealed a severe reduction of respiratory capacity: FVC was 0,70 L (19%) and FEV1 0,64 (19%). The arterial blood gas analysis showed diurnal hypercapnia (PaCO2 = 47 mmHg), and mild hypoxemia (PaO2 = 68 mmHg).

The overnight polysomnography demonstrated REM sleep hypopneas with REM sleep hypoventilation and continuous sleep stage-independent hypoventilation with apneas/hypopneas index (AHI) = 4 events/hour, and 31% of the time with arterial oxygen saturation (SaO2) less than 90% (T90 SaO2).

A non-invasive positive pressure ventilation (Trilogy; Philips Respironics, Murrysville, PA, USA) with nasal mask was proposed to the patient, but he immediately refused it due to claustrophobia and anxiety of not being able to call a family member, if necessary. Therefore a mouthpiece mask with an exhalation valve circuit was adopted. A pressure control (PC) with support of 8 cm H2O was preferred, which was gradually increased until a suitable tidal volume, an optimal value of peripheral saturation (confirmed by arterial blood gas analysis) and the stabilization of the heart rate were reached. The inspiration time was set at 1.3 sec, the expiratory positive air-way pressure (EPAP) at 0 cmH2O, the rise time amounted to 3 s. The respiratory rate was set at 0 breaths/min. The time of disconnection alarm was set at 15 minutes to allow the patient to speak and make breaks without triggering alarm. Blood gas analysis showed an improvement in oxygen saturation and the normalyzation of capnia (PaCO2 = 44 mmHg).

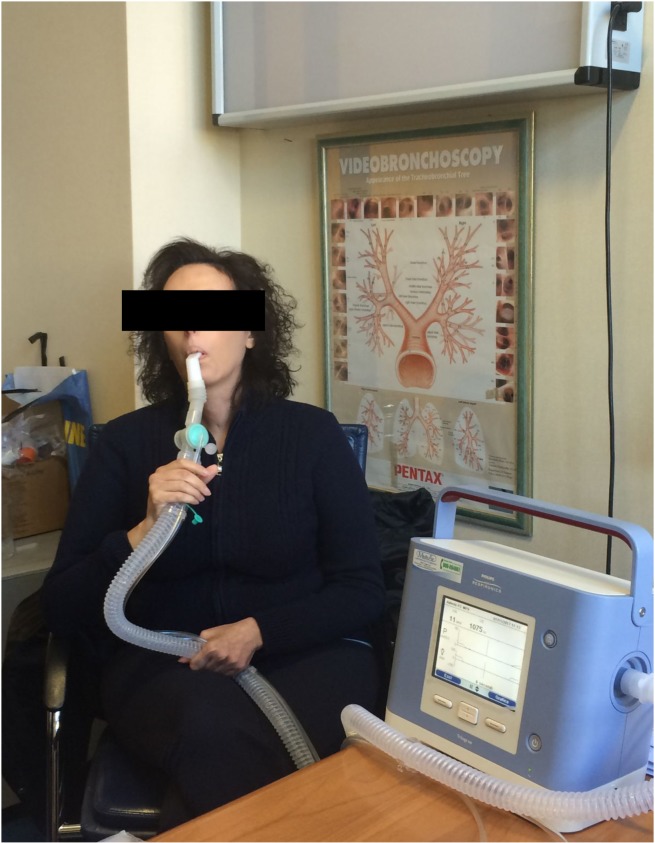

The patient tolerated well this ventilation mode with a good adaptation to the interface (Fig. 1). She accepted the treatment and continued the non-invasive mechanical ventilation at home.

Figure 1.

Steinert patient during MPV.

After two months of treatment, the patient was reevaluated. The analysis of the device usage showed a good compliance with the therapy, performed on average for 8 hours per day; furthermore an improvement of symptoms was reported.

Also the diurnal respiratory function showed an improvement after MPV, with values of FVC equal to 1.33 L (43%) vs 0,70 L (19%) and FEV1 equal to 1.16 L (43%) vs 0,64 L (19%), accompanied by an improvement of gas exchange (PaO2 = 78 mmHg and PaCO2 = 44 mmHg vs 68 mmHg and 47 mmHG, respectively.

Six months after the initiation of MPV, the improvement in pulmonary function and gas exchange were still present (FVC = 1.39 L (46%); FEV1 = 1.22 (46%); (PaO2 = 81 mmHg and PaCO2 = 42 mmHg. The overnight polysomnography showed a reduction (16% vs 31%) of the periods with a T90 SaO2 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Respiratory parameters observed pre and post mouthpiece treatment.

| pO2 | pCO2 | FVC | FEV1 | ESS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pre NIV | 68 | 47 | 0,71 | 0,64 | 21 |

| post NIV | 78 | 44 | 1,33 | 1,16 | 8 |

| after 6 months | 81 | 42 | 1,39 | 1,22 | 6 |

Discussion

The use of MPV has been previously described (6-8) in neuromuscular diseases. However no data exist on the use of MPV in patients with Steinert disease. These patients often require non-invasive mechanical ventilation and the choice of the proper interface can play a decisive role in the management and the compliance to the treatment, often hindered by complications such as skin lesions, excessive pressure and claustrophobia. In fact, it has been reported that the compliance with non-invasive ventilation is usually poor in patients with no subjective symptoms of respiratory failure and that the non-invasive ventilation (NIV) is more frequently abandoned in cases who experienced excessive leaks (9-12).

It has been reported that patients in general are satisfied with MPV, feel it as and efficient and comfortable mode of ventilation and prefer the mouthpiece rather than the nasal mask (10, 11). MPV can be also useful to promote a positive approach and a rapid acceptance of the new condition, taking into account that the patient's perception can have a positive effect on the adherence to NIV. In patients with muscular dystrophy muscle length tension relationship changes and muscle elasticity and plasticity are decreased, which results in impared inspiratory muscle function and decreased vital capacity. In addition, loss of deep breathing further increase the risk of alveolar collapse, hypoventilation and atelectasis (12). In the case described, we observed a stable improvement of vital capacity after treatment. One hypothesis to explain the improvements in lung volume is that application of NIV might help maintain lung and chest wall compliance (13), preventing hypoventilation and atelectasis which in turn may slow down the development of the restrictive respiratory pattern. It is possible that the improvement of vital capacity has a positive impact on alveolar ventilation by reducing the time with SaO2 spent below 90%. Therefore, the mouthpiece approach should always be considered in patients with neuromuscular diseases requiring NIV support. In our experience it can be successfully proposed to patients with Steinert's disease who have previously rejected the application of NIV due to tightness of the interface, or claustrophobia.

References

- 1.Harper PS. Myotonic dystrophy. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Machuca-Tzili L, Brook D, Hilton-Jones D, et al. Clinical and molecular aspects of the myotonic dystrophies: a review. Muscle Nerve. 2005;32:1–18. doi: 10.1002/mus.20301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meola G. Clinical aspects, molecular pathomechanisms and management of myotonic dystrophies. Acta Myol. 2013;32:154–165. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Santoro M, Masciullo M, Silvestri G, et al. Myotonic dystrophy type 1: role of CCG, CTC and CGG interruptions within DMPK alleles in the pathogenesis and molecular diagnosis. Clin Genet. 2016 Dec 19; doi: 10.1111/cge.12954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nigro Ge, Papa AA, Politano L. The heart and cardiac pacing in Steinerti disease. Acta Myol. 2012;31:110–116. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gregoretti C, Confalonieri M, Navalesi P, et al. Evaluation of patient skin breakdown and comfort with a new face mask for noninvasive ventilation: a multi-center study. Intensive Care Med. 2002;28:278–284. doi: 10.1007/s00134-002-1208-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bédard ME, McKim DA. Daytime mouthpiece for continuous noninvasive ventilation in individuals with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Respir Care. 2016;61:1341–1348. doi: 10.4187/respcare.04309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Toussaint M, Steens M, Wasteels G, et al. Diurnal ventilation via mouthpiece: survival in end-stage Duchenne patients. Eur Respir J. 2006;28:549–555. doi: 10.1183/09031936.06.00004906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boussaïd G, Lofaso F, Santos DB, et al. Factors influencing compliance with non-invasive ventilation at long-term in patients with myotonic dystrophy type 1: A prospective cohort. Neuromuscul Disord. 2016;26:666–674. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2016.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nardi J, Leroux K, Orlikowski D. Home monitoring of daytime mouthpiece ventilation effectiveness in patients with neuromuscular disease. Chron Respir Dis. 2016;13:67–74. doi: 10.1177/1479972315619575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khirani S, Ramirez A, Delord V, et al. Evaluation of ventilators for mouthpiece ventilation in neuromuscular disease. Respir Care. 2014;59:1329–1337. doi: 10.4187/respcare.03031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chiou M, Bach JR, Jethani L, et al. Active lung volume recruitment to preserve vital capacity in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. J Rehabil Med. 2017;49:49–53. doi: 10.2340/16501977-2144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brasil Santos D, Vaugier I, Boussaïd G, et al. Impact of noninvasive ventilation on lung volumes and maximum respiratory pressure in Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy. Respir Care. 2016;61:1530–1535. doi: 10.4187/respcare.04703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]