Abstract

Raman microspectroscopy was used to quantify freezing response of cells to various cooling rates and solution compositions. The distribution pattern of cytochrome c in individual cells was used as a measure of cell viability in the frozen state and this metric agreed well with the population-averaged viability and trypan blue staining experiments. Raman imaging of cells demonstrated that intracellular ice formation (IIF) was common and did not necessarily result in cell death. The amount of intracellular ice as well as ice crystal size played a role in determining whether or not ice inside the cell was a lethal event. Intracellular ice crystals were colocated to the sections of cell membrane in close proximity to extracellular ice. Increasing the distance between extracellular ice and cell membrane decreased the incidence of IIF. Reducing the effective stiffness of the cell membrane by disrupting the actin cytoskeleton using cytochalasin D increased the amount of IIF. Strong intracellular osmotic gradients were observed when IIF was present. These observations support the hypothesis that interactions between the cell membrane and extracellular ice result in IIF. Raman spectromicroscopy provides a powerful tool for observing IIF and understanding its role in cell death during freezing, and enables the development, to our knowledge, of new and improved cell preservation protocols.

Introduction

Cryopreservation is used to stabilize cells for a variety of applications including diagnosis and treatment of disease. Since the 1970s, the variation in survival as a function of cooling rate has been observed for a wide variety of cell types (1). Most cell types exhibit an inverted U-shaped variation in survival with cooling rate. For cooling rates above the optimum, there is a rapid decrease in survival with increasing cooling rate and, similarly, there is a rapid decrease in survival at cooling rates less than the optimum. At high cooling rates, it has been hypothesized that the formation of ice inside the cell (i.e., intracellular ice formation, IIF) causes damage to the cells and results in the loss of viability with increasing cooling rates (2, 3, 4). However, the mechanism of IIF is still being debated. There are three main hypotheses: 1) Mazur (5) hypothesizes that extracellular ice crystal could grow through pores in the membrane and induce nucleation in the cell; 2) Asahina (6) holds that direct disruption of cell membrane causes IIF; and 3) Toner et al. (4) propose that surface-catalyzed nucleation was responsible for IIF. Experimental support for each of these hypotheses is limited. Low-temperature light microscopy studies have correlated darkening of the cell during freezing with IIF (see (3) for review) and high-speed image acquisition and two-photon microscopy have improved the spatial and temporal resolution of cell freezing studies (7, 8).

Raman microspectroscopy has been a useful tool for understanding cell response to freezing as it permits label-free interrogation of cells and can be used to chemically identify the thermodynamic state of water inside the cell (i.e., liquid water versus ice) (9, 10). Furthermore, the high spatial resolution of Raman microspectroscopy and the ability to distinguish subcellular structures such as the cell membrane and the mitochondria imply that this tool could be used to further our understanding of IIF and its causes. The ability to freeze cells and determine viability using Raman will enable us to characterize directly the influence of IIF on cell viability. We will also characterize ice crystal size, intracellular concentration of cryoprotective agent, and proximity of external ice to the cell membrane. These studies provide direct evidence as to mechanisms of IIF, which will advance our understanding of freezing damage of cells.

Materials and Methods

Jurkat cell culture

The studies utilized Jurkat cells (TIB-1522; American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA) as the model cell for lymphocytes, as there is much interest in understanding the freezing responses of lymphocytes for therapeutic application. Jurkat cells were cultured by incubating at 37°C with 5% CO2 in media composed of high glucose RPMI 1640 (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA), and 10% fetal bovine serum (Qualified FBS; Life Technologies). Cells were grown in suspension and maintained at a concentration of 1–2 × 106 cells/mL. Cells samples were prepared by washing and centrifuging cells twice in Dulbecco’s Phosphate Buffered Saline at 1000 rpm for 5 min. The cells were then suspended in each experimental solution of interest and frozen using a thermally controlled stage described in a previous publication (11).

Confocal Raman system

Confocal Raman microspectroscopy measurements were conducted using a Confocal Raman Microscope System Alpha 300R (WITec, Ulm, Germany) with a UHTS300 spectrometer and DV401 CCD detector with 600/mm grating. The WITec spectrometer was calibrated with a Mercury-argon lamp. A wavelength of 532 nm Nd:YAG laser was used as an excitation source. The laser was transmitted to the microscopy in a sinlger fiber. A 100× air objective (NA 0.90; Nikon Instruments, Melville, NY) was used for focusing the 532-nm excitation laser to the sample. The laser at the objective was 10 mW, as measured by an optical power meter (Thorlabs, Newton, NJ). The resolution of the microscope was ∼296 nm, based on Abbe’s diffraction formula for lateral resolution.

Raman image/spectra analysis

Raman images were assembled by integrating the spectrum at each pixel based on characteristic wavenumbers of common intracellular and extracellular materials (Fig. 1). Cells were frozen to a holding temperature of −50°C and held for 20 min before imaging. The Raman spectra/image obtained for the same cell with a hold time of 20, 80, and 140 min remained the same (Fig. S1), suggesting that heat from laser and photodamage/photobleaching did not affect the measurements. Each image had 60 × 60 pixels with an integration time of 0.2 s for each pixel; as a result, it took 12 min to image one single cell. Table 1 lists the Raman signals observed and the associated wavenumbers selected for these studies. The release of cytochrome c from mitochondria will be used as a measure of cell viability. Cytochrome c has strong Raman signals at 750, 1127, 1314, and 1585 cm−1 (12). For these experiments, the peak centered at 1127 cm−1 was used to generate Raman images of cytochrome c. The Raman signals selected for this study do not overlap with each other; as a result, multivariate data analysis is not required.

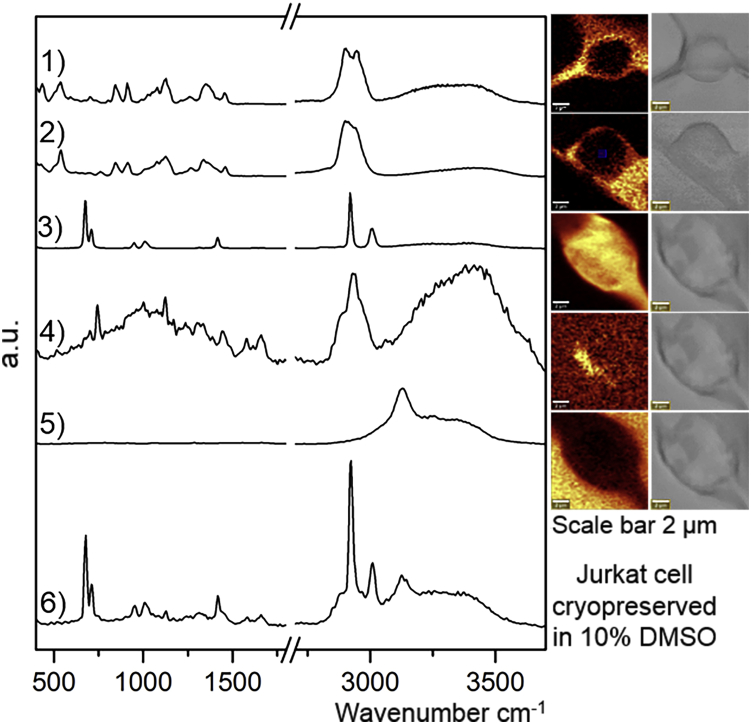

Figure 1.

Raman spectra of 1) trehalose, 2) dextran, 3) DMSO, 4) cytochrome c from cell, 5) ice with corresponding Raman images, and 6) Raman spectra of Jurkat cell cryopreserved in 10% DMSO. Images on the right are rendered based on the specific signal on the left, and light microscopy images are given as a reference. All cells imaged are alive. To see this figure in color, go online.

Table 1.

Wavenumber Assignments for Raman Spectra

Vial freezing experiments and post-thaw assessment

Cells were cryopreserved using a controller rate freezer (Series III Kryo 10; Planer, Middlesex, UK) in cryopreservation solutions of interest using various cooling rates (0.5, 1, 3, 10°C /min). Acridine orange/propidium iodide (AO/PI; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) staining was used to determine viability of cells post-thaw. Briefly, cells were combined with AO/PI, loaded into a hemocytometer, and counted manually using a fluorescent microscope. At least 200 total cells were counted for each experimental condition tested. Recovery was calculated directly by dividing the number of live cells post-thaw by the number of live cells pre-freeze.

Moran’s I value

Spatial localization (quantified using Moran’s I (13)) of cytochrome c was used as a marker for viability in this study. Moran’s I tool is a measure of spatial correlation based on both signal locations and intensity. A value of −1 for Moran’s I indicates perfect dispersion of signals, +1 indicates perfect correlation of signals, and 0 indicates random distribution of signals. Raman images of cytochrome c of live cells were obtained and compared to the viability of the cell determined using trypan blue exclusion (Fig. 2 C). Raman images of cytochrome c for live cells were processed by transforming the image to grayscale and subtracting background using the software ImageJ (14)(Fig. 3 A). Moran’s I value was calculated in GeoDa software by using the Univariate Moran’s I function based on a weight matrix calculated from each pixel’s eight nearest neighbors (15).

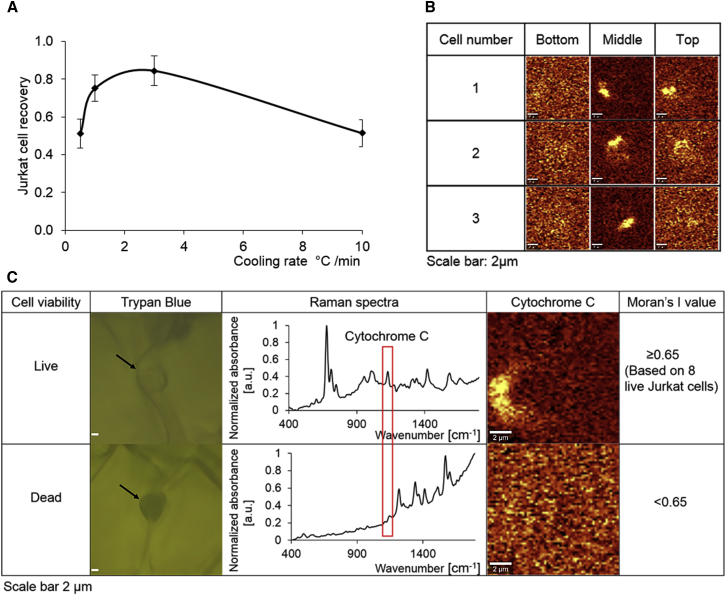

Figure 2.

(A) Shown there is Jurkat cell recovery in 10% DMSO as a function of cooling rates (error bars represent SE of the mean, n = 3). Measurements were made at 0.5, 1, 3 and 10°C/min. (B) Shown are Raman images of cytochrome c for three different frozen cells at three focal planes: bottom (middle −2 μm), middle, and top (middle +2 μm). Cells were frozen at 10°C/min down to −50°C in 10% DMSO solution. The scale bar represents 2 μm. (C) Shown here are live and dead Jurkat cells confirmed by trypan blue with corresponding Raman spectra of cytochrome c, Raman images of cytochrome c, and Moran’s I values. Cells were frozen at 10°C/min down to −50°C in 10% DMSO with trypan blue solution. The scale bar represents 2 μm. To see this figure in color, go online.

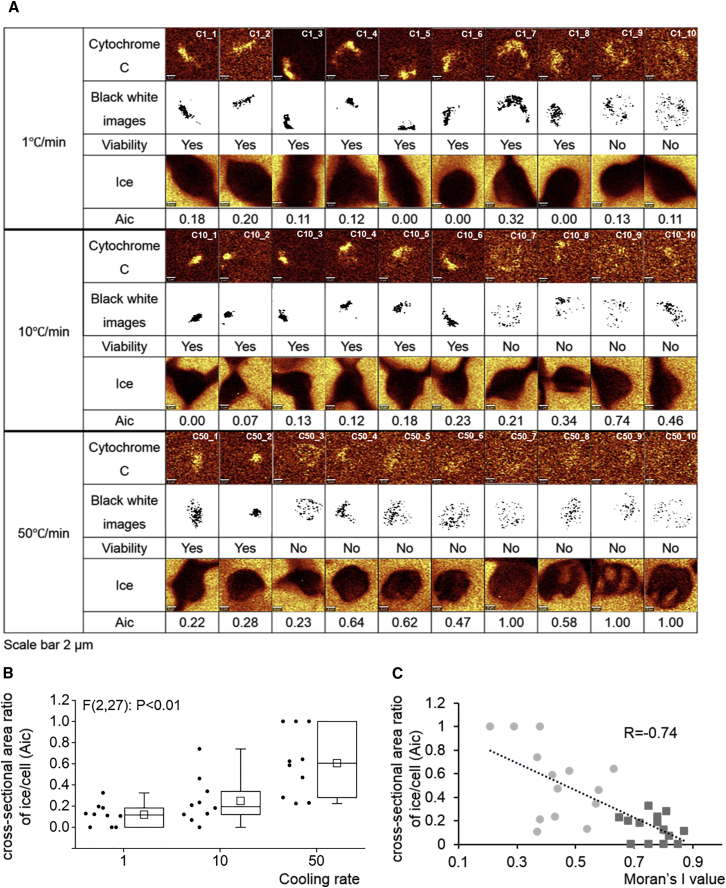

Figure 3.

(A) Shown here are Raman images and black-and-white images of cytochrome c and ice, cell viability, and Aic for cells cryopreserved at different cooling rates (1, 10 and 50°C/min) in 10% DMSO solution down to −50°C. The scale bar represents 2 μm. The cell tracking number is given in the upper-right corner of the Raman images. (B) Shown here is Aic grouped by cooling rates (C/min). Ends of the whiskers represent the minimum and maximum of all of the data. The bottom and top of the box are the first and third quartiles, and the line inside the box is the median. The square inside the box is the average. One-way ANOVA analysis shows a statistically significant difference of the ratio among cooling rates (p < 0.01). (C) Shown here is Aic as a function of Moran’s I value for all the cells tested. Correlation coefficient R was −0.74. Cells represented by circles are not viable and cells represented by squares are viable. To see this figure in color, go online.

Distance between the cell membrane and extracellular ice

Dextran or trehalose forms a thin layer between the cell membrane and extracellular ice. The thickness of this solute-rich layer is used to approximate the distance between the cell membrane and extracellular ice. The distance between the cell membrane and extracellular ice was measured at 15° intervals around the cell in the software ImageJ (14) based on Raman images of dextran or trehalose.

Statistics

Averages plus or minus standard error of the mean are reported unless otherwise noted. Student’s t-tests or one-way ANOVA were used to determine the statistical difference of different experimental groups.

Results

IIF and viability

To determine the range of cooling rates associated with “fast” cooling, cells were resuspended in 10% DMSO solution and frozen at a constant cooling rate (0.5, 1, 3, and 10°C/min). Post-thaw cell recovery is plotted as a function of cooling rate in Fig. 2 A and as expected, the curve took the form of a typical inverted U shape with 1–3°C /min being “optimum” and cooling rates above that were considered fast and therefore associated with IIF.

The ability to correlate IIF with viability requires determination of a metric for viability that can be detected using Raman microspectroscopy. For this investigation, the release of cytochrome c from mitochondria was used as a measure of cell viability and was well correlated with trypan blue exclusion, a widely accepted measure of viability. Cells were frozen in solutions containing trypan blue and interrogated using Raman microspectroscopy. Qualitative observations of these cells confirmed results that were as expected: trypan-blue negative cells (live cells) had cytochrome c signals that were strong and localized, whereas trypan-blue positive cells (dead cells) showed no distinguishable cytochrome c peak (Fig. 2 C).

To determine a threshold level for the distribution of cytochrome c associated with viability, additional studies were performed with cells frozen in 10% DMSO supplemented with trypan blue. Raman images of cytochrome c distribution in these trypan-blue negative cells were analyzed and values of Moran’s I were determined. The lowest Moran’s I value for Raman images of cytochrome c in these trypan-blue negative cells (live cells) was 0.65. As a result, a Moran’s I value of 0.65 was used as a threshold level to distinguish live and dead cells. Raman images obtained at different focal planes in the frozen cell showed that images of cytochrome c at the middle (center) of the cell provided the strongest signal (Fig. 2 B).

The viability of cells frozen at different cooling rates, specifically, 1, 10, and 50°C/min, were determined for multiple cells. Eighty-percent of cells cryopreserved at 1°C/min were alive, 60% of cells cryopreserved at 10°C/min were alive, and 20% of cell cryopreserved at 50°C/min were alive (Fig. 3 A). Taken as a whole, cell viability measured for a population of single cells agreed with the population-averaged viability given in Fig. 2 A.

The spectra obtained from each cell could also be analyzed for intracellular ice formation. Each cell examined is given a unique identifier so that they can be followed in the analysis given below.

Intracellular ice formation was quite common; it was detected in seven of the 10 cells at 1°C/min, nine of the 10 cells at 10°C/min, and 10 of the 10 cells at 50°C/min. The relative amount of intracellular ice in each cell could be estimated based on the ratio of the cross-sectional area of ice to the cross-sectional area of the cell (denoted as “Aic” in the following text) (Fig. 3 A). Aic of each cell was calculated as a function of cooling rates (Fig. 3 B). Aic increased with increasing cooling rate, as would be expected. Aic was also plotted as a function of Moran’s I value in Fig. 3 C, which showed that, in general, live cells had less ice than dead cells, but the variation in each population (alive or dead) was substantial.

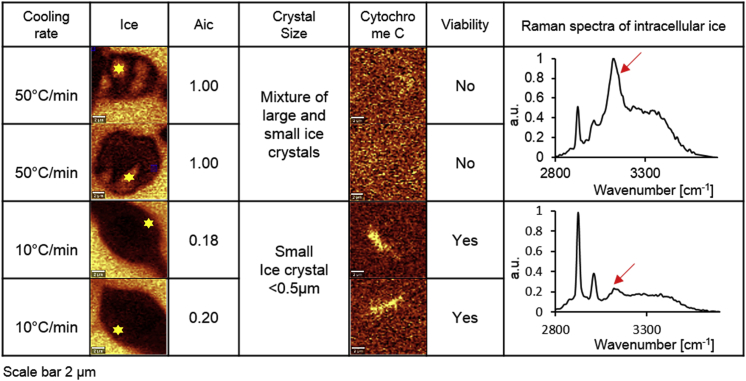

The average ice crystal size for IIF was calculated based on the Raman images obtained. Most cells had only small ice crystals present (<0.5 μm) for all of the cooling rates tested and all viable cells with IIF had small ice crystals. The presence of large ice crystals (2–3 μm) was observed most commonly at high cooling rates, and cells with large ice crystals were always dead (Fig. 4). Large and small ice crystals tended to be located in different regions of the cell. Small ice crystals were only found at the edge of the cell adjacent to the extracellular ice. Large chunks of pure ice crystals were located both at the edge of the cell and at center of cell.

Figure 4.

Shown here are Raman images of two different kinds of intracellular ice: large chunks of pure ice crystals and small ice crystals interspersed with cytosol with corresponding Aic, crystal size, Raman images of cytochrome c, viability, and Raman spectra of intracellular ice. Raman spectra of intracellular ice was based on location of the “star” in the Raman image of ice. The arrow indicates the Raman peak of ice. Cells were frozen in 10% DMSO down to −50°C at 50 or 10°C/min. The scale bar represents 2 μm. To see this figure in color, go online.

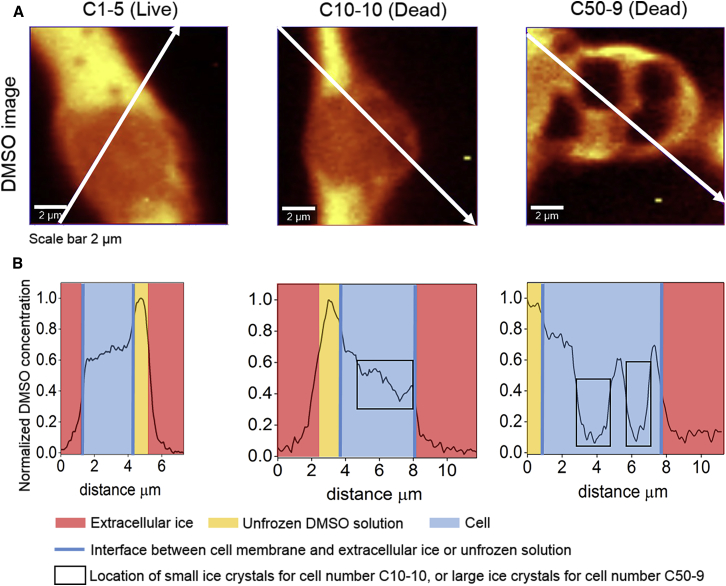

Removal of water in the form of ice can influence the intracellular concentration of DMSO and introduce concentration gradients. To quantify solute concentration redistribution, Raman images of one cell at each cooling rate were analyzed for DMSO concentration (Fig. 5 A). The spectra for a region containing extracellular ice, cell, and unfrozen DMSO solution (see white arrow) was analyzed. Normalized DMSO concentration (peak intensity of DMSO at each data point along the arrow divided by maximum peak intensity of DMSO in the unfrozen extracellular solution) was plotted as a function of horizontal distance of the arrow from its start point. For the cell frozen at 1°C/min with no IIF, DMSO concentration inside the cell was relatively uniform. The cell frozen at 10°C/min contained small ice crystals and DMSO concentration inside the cell showed greater variation across ice crystals. For the cell frozen at 50°C/min with large ice crystals, DMSO concentration inside the cell changes substantially across the cell (Fig. 5 B). The maximum intracellular DMSO concentration did not vary significantly across the different cooling rates; concentration gradients did, however, vary significantly.

Figure 5.

(A) Shown here are Raman images of DMSO for one cell at each cooling rate (1, 10, and 50°C/min). The cell tracking number and cell viability were given above the figure. The white arrow goes through different regions of the image and represents the location where peak intensity of DMSO at 673 cm−1 was obtained. (B) Given here is the normalized DMSO concentration (peak intensity of DMSO at each data point along the arrow divided by maximum peak intensity of DMSO in the unfrozen extracellular solution) plotted as a function of horizontal distance of the arrow from its start point. To see this figure in color, go online.

The cell membrane, extracellular ice, and IIF

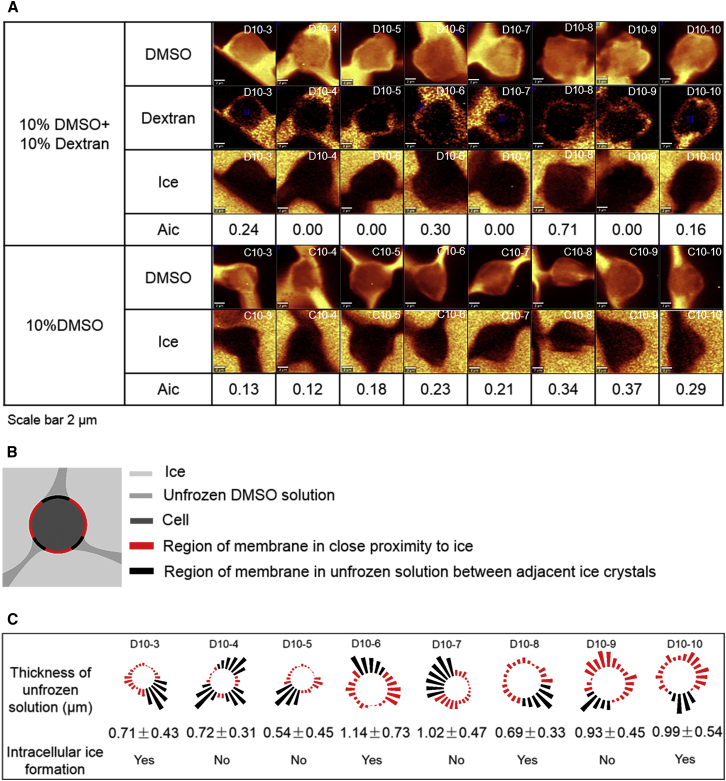

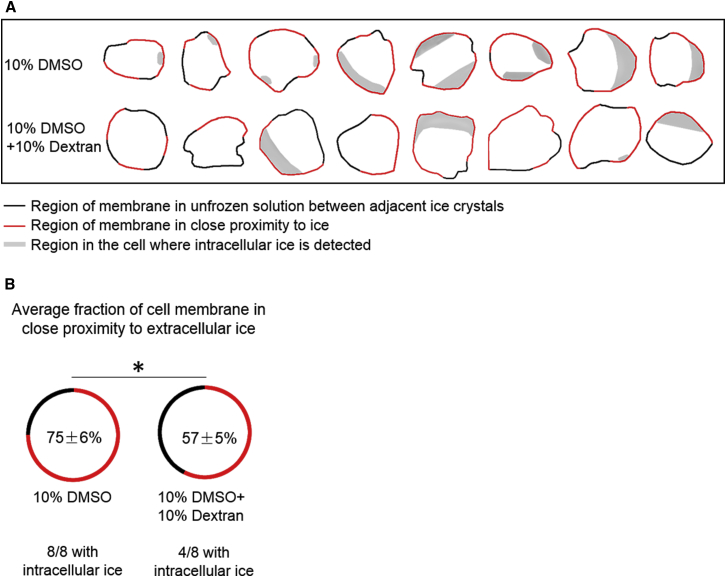

The next phase of the investigation involved characterizing the interaction among external ice, the cell membrane, and IIF. Cells were cryopreserved in 10% DMSO or 10% DMSO + 10% dextran with a cooling rate of 10°C/min (Fig. 6 A). The images were analyzed for IIF and Aic Biological cells are typically trapped in the unfrozen solution between adjacent ice crystals (16). Two different regions were designated: 1) regions where extracellular ice is in close proximity to the cell membrane; and 2) regions between adjacent ice crystals in which the cell membrane is distant from extracellular ice (Fig. 6 B). The proximity of the cell membrane to extracellular ice was approximated by measuring the thickness of unfrozen solution between the cell and extracellular ice crystals (Fig. 6 C). Images were also analyzed for the physical location of ice inside the cell and fraction of cell membrane in close proximity to extracellular ice (Fig. 7, A and B).

Figure 6.

(A) Shown here are Raman images of DMSO, dextran, ice, and Aic for cells frozen in 10% DMSO + 10% dextran solution at 10°C/min down to −50°C. Also shown are Raman images of DMSO, ice, and Aic for cells frozen in 10% DMSO solution at 10°C/min down to −50°C. The scale bar represents 2 μm. The cell tracking number is given in the upper-right corner of the Raman images. (B) Given here is a schematic diagram of a frozen cell. (C) Bars represent the thickness of unfrozen solution measured at 15° intervals for cells frozen in 10% DMSO + 10% dextran solution to show distance from the cell membrane. The average thickness (with standard deviation) for region of membrane in close proximity to extracellular ice as well as intracellular ice formation is given below the figure. The cell tracking number is given above. To see this figure in color, go online.

Figure 7.

(A) Given here is the schematic diagram of two different segments of cell membrane and the location of intracellular ice for cells frozen in 10% DMSO and 10% DMSO + 10% dextran solution. (B) Given here is the fraction of cell membrane in close proximity to extracellular ice for cells frozen in 10% DMSO and 10% DMSO + 10% dextran solution. There was a statistically significant difference between cells frozen in 10% DMSO and 10% DMSO + 10% dextran solution (SE, n = 8, p <0.05). To see this figure in color, go online.

For cells frozen in 10% DMSO at 10°C/min, eight out of eight (100%) of the cells exhibited IIF and the Aic varied from 0.1 to 0.4. The distance between extracellular ice and the cell membrane was less than the resolution of the imaging system (∼296 nm). For all of the cells studied, IIF was located in the region of the cell where the cell membrane was adjacent to extracellular ice (versus adjacent to gaps between adjacent ice crystals) and the fraction of the cell membrane adjacent to extracellular ice was 75 ± 6%. In contrast, when cells were frozen in 10% DMSO + 10% dextran, only four out of eight cells exhibited IIF and the Aic ranged between 0.12 and 0.37. The distance between the cell membrane and the extracellular ice was greater than that observed for 10% DMSO alone and ranged between 0.54 ± 0.45 and 1.14 ± 0.73 μm (Fig. 6 C). IIF was also located in the region of the cell where the cell membrane was adjacent to extracellular ice, but the fraction of the cell membrane adjacent to extracellular ice was reduced to 57 ± 5%. The ratio of intracellular to extracellular dextran concentration defined by the ratio of intracellular to extracellular Raman peak intensity at 850 cm−1 ranged from 5 to 29%, suggesting dextran mainly stayed outside the cell.

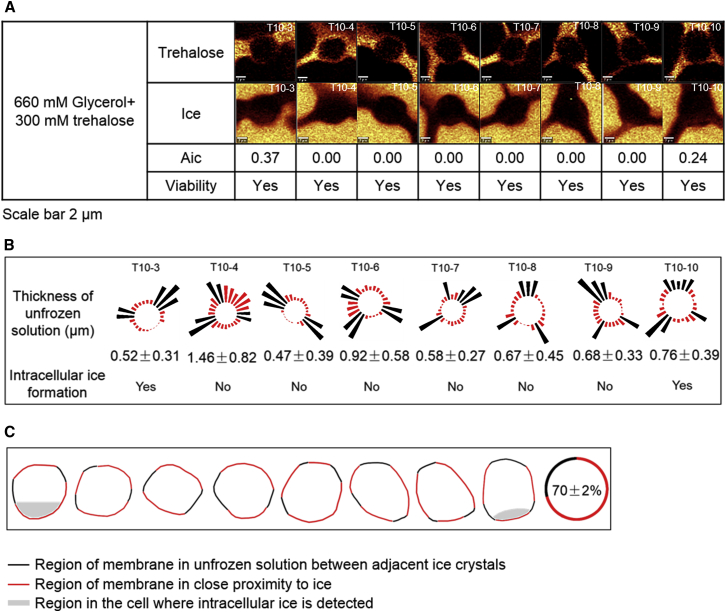

To test whether similar effects were observed with other cryoprotective agents, Jurkat cells were frozen in 660 mM glycerol + 300 mM trehalose solution down to −50°C at 10°C/min. Raman images were rendered for trehalose and ice (Fig. 8 A). Only two of the eight cells showed IIF and the Aic of the cells ranged from 0.0 to 0.37. All of the cells imaged were viable. As with cells frozen in DMSO, intracellular ice was located adjacent to the portion of the cell membrane that was in close proximity to extracellular ice (Fig. 8 C). The distance between the cell membrane and extracellular ice ranged between 0.48 ± 0.39 and 1.46 ± 0.82 μm, which was similar to the distance observed with the 10% DMSO + dextran solution (Fig. 8 B).

Figure 8.

(A) Given here are Raman images of trehalose, ice, and Aic, and viability for cells frozen in 660 mM glycerol + 300 mM trehalose at 10°C/min down to −50°C. The scale bar represents 2 μm. The cell tracking number is given in the upper-right corner of the Raman images. (B) Bars represent the thickness of unfrozen solution measured at 15° intervals for cells frozen in 660 mM glycerol + 300 mM trehalose solution to show distance from the cell membrane. The average thickness (with SD) for the region of the membrane in close proximity to ice as well as intracellular ice formation was given below the figure. The cell tracking number is given above. (C) Shown here is the schematic diagram of two different segments of cell membrane and the location of intracellular ice. The average fraction of the cell membrane in close proximity to extracellular ice is given at the far right. To see this figure in color, go online.

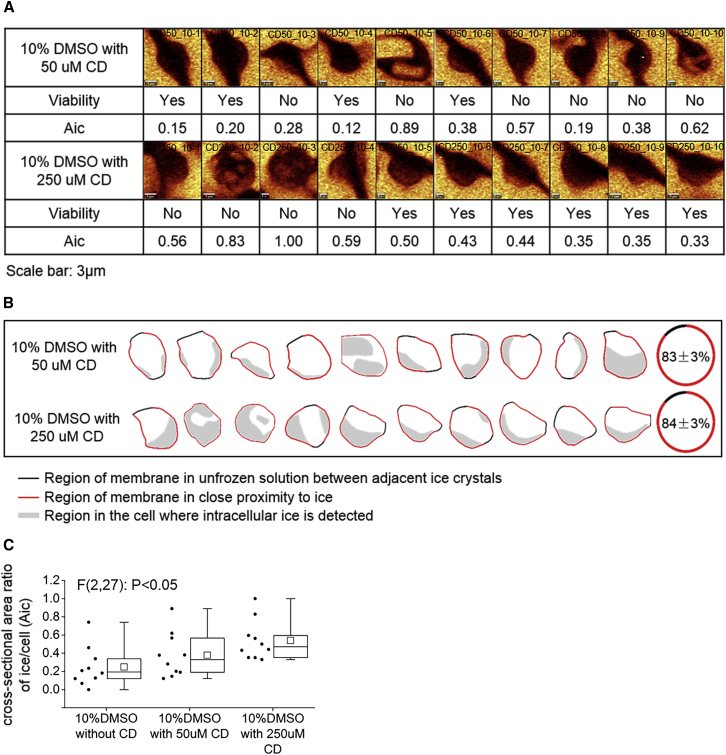

The plasma membrane does not act in isolation but interacts with other structures in the cell, particularly, the cytoskeleton (17). Disrupting the cytoskeleton can result in release of the membrane reservoir and a reduction in membrane stiffness (18). To determine the influence of releasing the membrane reservoir on IIF, Jurkat cells were incubated with 50- or 250-μM cytochalasin D (CD) for 30 min followed by freezing in 10% DMSO at 10°C/min. Raman images were rendered for ice (Fig. 9 A). The fraction of cells exhibiting IIF was the same for all conditions tested (100%), but Aic increased significantly with increasing concentration of CD (Fig. 9 C). Large chunks of ice were observed in two of the 10 cells for experiments in which CD was present. It is noteworthy that the fraction of cell membrane in proximity to extracellular ice was high for all of the cells studied (∼83%). It was also true that cells with large chunks of pure ice crystals were all dead, whereas cells with small ice crystals could be dead or alive. Intracellular ice crystals were also colocated to the sections of cell membrane in close proximity to extracellular ice (Fig. 9 B). The distance between the cell membrane and the extracellular ice was still less than the resolution of the imaging system (296 nm).

Figure 9.

(A) Given here are Raman images of ice, viability, and Aic for cells frozen in 10% DMSO down to −50°C at 10°C/min after incubation with CD for 30 min (50 and 250 μM). The scale bar represents 3 μm. The cell tracking number is given in the upper-right corner of the Raman images. (B) Given here is the schematic diagram of two different segments of cell membrane and the location of intracellular ice for cells frozen in 10% DMSO with 50- or 250-μM CD. The average fraction of the cell membrane in close proximity to extracellular ice is given at the far right. (C) Given here is the Aic for cells frozen in 10% DMSO without CD, with 50- and 250-μM CD. Ends of the whiskers represent the minimum and maximum of all of the data. The bottom and top of the box are the first and third quartiles, and the line inside the box is the median. The square inside the box is the average. One-way ANOVA analysis shows the statistically significant difference of the ratio among different groups (p < 0.05). To see this figure in color, go online.

Discussion

IIF and viability

The impact of conventional low-temperature microscopy techniques has been limited because observations of cell responses at low temperature could not be correlated to viability on a cell-by-cell basis. The notable exception is Stracke et al. (8), who used two-photon microscopy in combination with fluorescent dyes to study the location of ice crystals and cell viability. This study establishes our ability to correlate cytochrome c distribution, a signal that can be detected using Raman microspectroscopy, with trypan blue staining for individual cells. Conventional fluorescent dyes or trypan blue cannot be used during Raman microspectroscopy as it interferes with detection of the other signals of interest (water, ice, and DMSO). Other spectroscopic studies have also used cytochrome c as a marker for cell viability (12, 19).

It is noteworthy that similar studies were carried out using mesenchymal stem cells but similar responses were not observed. Specifically, localization of cytochrome c was not observed, suggesting that the mechanism of cell death may vary from cell type to cell type. The cytochrome c activity observed in this study may explain the significant post-thaw apoptosis that has been observed for lymphocytes (20, 21).

A variety of earlier investigations have shown that IIF is a lethal event (5, 22, 23). This investigation suggests that IIF alone may not be a lethal event. Small amounts of IIF are common even at slow cooling rates and are not necessarily lethal. The presence of large ice crystals and/or significant fraction of the cells containing ice (Aic > 0.32) are associated with lethal damage. This outcome agrees with other studies that have demonstrated that intracellular ice formation is not always lethal (24, 25, 26, 27). Although the threshold value for Aic above which cells were considered dead could be different for cells cryopreserved in different cryoprotectant compositions (not applicable to cells cryopreserved with glycerol + trehalose because all cells were alive; cells incubated with CD before cryopreserved with 10% DMSO, Aic: 0.50), the same conclusion can be reached that IIF is not always a lethal event.

The removal of water in the form of ice inside the cell can cause changes in the intracellular DMSO concentration (or concentration gradients), which could be a potential mechanism of damage associated with IIF formation. Specifically, solute polarization adjacent to the IIF could produce a high-localized concentration that would dissipate after ice growth had stopped. The image acquisition time for Raman is long enough that transient changes in concentration resulting from IIF cannot be captured, so the analysis here represents more of an equilibrium analysis of DMSO concentration across the cell in the presence or absence of IIF. The maximum concentration inside the cell, however, did not change with the presence of IIF for the conditions studied. Alternatively, IIF can damage the cell through disruption of the cytoskeleton. Unfortunately, it is not possible to distinguish the cytoskeleton from other intracellular proteins using Raman, so it is also not possible to prove or disprove whether IIF damages the cytoskeleton.

The cell membrane, extracellular ice, and IIF

IIF is located adjacent to the cell membrane and, in particular, the portion of the cell membrane adjacent to extracellular ice. As the fraction of cell membrane in close proximity to extracellular ice increases, the fraction of cells with IIF increases. The colocation of ice and the cell membrane was observed for a range of solution compositions and cooling rates. These studies also observed that as the distance between the cell membrane and extracellular ice decreased, the fraction of cells with IIF increased. These outcomes suggest that interaction between the cell membrane and extracellular ice is responsible for IIF. These studies provide further insight into potential mechanisms of action for cryoprotective agents. The results of this investigation suggest that one mechanism of action may be actually increasing the separation of the membrane with extracellular ice.

Further support for the hypothesis that the interaction between cell membrane and extracellular ice is the reason for IIF can be found in the studies of cells incubated with varying concentrations of CD before freezing. Disruption of the actin cytoskeleton increases the amount of available membrane material (18) and in this study, increases the fraction of the cell containing ice. It is noteworthy that the use of CD can bring about changes in both membrane stiffness and permeability, and the increase in the amount of ice present in the cell may reflect that influence.

Failure of the cell membrane was not observed for any of the experimental conditions tested in this investigation. Both dextran and trehalose are large molecules that do not typically penetrate the cell. Raman spectra were analyzed and showed little penetration of those molecules into the cell for both cells with IIF as well as those without IIF. Other studies suggested that disruption of the cell membrane causes IIF. Asahina (6) suggested that destruction of the protoplasmic structure of the cell surface was the reason for IIF. Muldrew and McGann (28) also proposed that cell membrane damage resulting from osmotic pressure across the membrane caused IIF.

Conclusions

Raman microspectroscopy was utilized to investigate the freezing response of cells to different cooling rates and freeing media compositions. We confirmed that ice alone does not necessarily result in cell death and the amount of intracellular ice as well as ice crystal size affects cell viability. Intracellular ice crystals were further found colocated to the area of the cell membrane that was in close proximity to an extracellular ice crystal. Increasing the distance between the cell membrane and the extracellular ice resulted in decreasing IIF. Disruption of the actin cytoskeleton with CD increased the amount of intracellular ice formation. IIF does, however, produce large gradients in DMSO concentration that could be potentially damaging. The results of these studies support the hypothesis that interaction between cell membrane and extracellular ice results in IIF, and Raman spectromicroscopy, to our knowledge, provides a new way to directly observe these phenomena.

Author Contributions

G.Y. designed research, performed experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript. Y.R.Y. designed research and analyzed data. K.P. designed research and wrote the manuscript. A.H. designed research and wrote the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by R21EB016247 and R25HL128372. K.P. acknowledges support from the University of Minnesota Doctoral dissertation fellowship. Parts of this work were carried out in the Characterization Facility, University of Minnesota, a member of the National Science Foundation (NSF)-funded Materials Research Facilities Network (www.mrfn.org) via the Materials Research Science and Engineering Centers (MRSEC) program.

Editor: Arne Gericke.

Footnotes

One figure is available at http://www.biophysj.org/biophysj/supplemental/S0006-3495(17)30516-7.

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Leibo S.P., Mazur P. The role of cooling rates in low-temperature preservation. Cryobiology. 1971;8:447–452. doi: 10.1016/0011-2240(71)90035-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Toner M., Cravalho E.G., Armant D.R. Cryomicroscopic analysis of intracellular ice formation during freezing of mouse oocytes without cryoadditives. Cryobiology. 1991;28:55–71. doi: 10.1016/0011-2240(91)90008-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Toner M. Vol. 2. JAI Press; London, UK: 1993. Nucleation of ice crystals inside biological cells; pp. 1–51. (Advances in Low-temperature Biology). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Toner M., Cravalho E.G., Karel M. Thermodynamics and kinetics of intracellular ice formation during freezing of biological cells. J. Appl. Phys. 1990;67:1582–1593. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mazur P. The role of cell membranes in the freezing of yeast and other single cells. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1965;125:658–676. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1965.tb45420.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Asahina E. Frost injury in living cells. Nature. 1962;196:445–446. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stott S.L., Karlsson J.O.M. Visualization of intracellular ice formation using high-speed video cryomicroscopy. Cryobiology. 2009;58:84–95. doi: 10.1016/j.cryobiol.2008.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stracke F., Kreiner-Møller A., Zimmerman H. Cryopreservation and Freeze-drying Protocols. 3rd Ed. Springer; Berlin, Germany: 2015. Laser scanning microscopy in cryobiology; pp. 229–241. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dong J., Malsam J., Aksan A. Spatial distribution of the state of water in frozen mammalian cells. Biophys. J. 2010;99:2453–2459. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.08.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pollock K., Yu G., Hubel A. Combinations of osmolytes, including monosaccharides, disaccharides, and sugar alcohols act in concert during cryopreservation to improve mesenchymal stromal cell survival. Tissue Eng. Part C Methods. 2016;22:999–1008. doi: 10.1089/ten.tec.2016.0284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dong J., Hubel A., Aksan A. Freezing-induced phase separation and spatial microheterogeneity in protein solutions. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2009;113:10081–10087. doi: 10.1021/jp809710d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Okada M., Smith N.I., Fujita K. Label-free Raman observation of cytochrome c dynamics during apoptosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:28–32. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1107524108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moran P.A.P. Notes on continuous stochastic phenomena. Biometrika. 1950;37:17–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schneider C.A., Rasband W.S., Eliceiri K.W. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat. Methods. 2012;9:671–675. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Anselin L., Syabri I., Kho Y. GeoDa: an introduction to spatial data analysis. Geogr. Anal. 2006;38:5–22. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rapatz G., Luyet B. Microscopic observations on the development of the ice phase in the freezing of blood. Biodynamica. 1960;8:195–239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Luna E.J., Hitt A.L. Cytoskeleton–plasma membrane interactions. Science. 1992;258:955–964. doi: 10.1126/science.1439807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Raucher D., Sheetz M.P. Characteristics of a membrane reservoir buffering membrane tension. Biophys. J. 1999;77:1992–2002. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77040-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zoladek A., Pascut F.C., Notingher I. Non-invasive time-course imaging of apoptotic cells by confocal Raman micro-spectroscopy. J. Raman Spectrosc. 2011;42:251–258. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hubel A. Advances in Biopreservation. CRC Press; Boca Raton, FL: 2006. Cellular preservation: gene therapy cellular metabolic engineering; pp. 143–156. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stroh C., Cassens U., Los M. The role of caspases in cryoinjury: caspase inhibition strongly improves the recovery of cryopreserved hematopoietic and other cells. FASEB J. 2002;16:1651–1653. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0034fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mazur P. Physical and chemical basis of injury in single-celled microorganisms subjected to freezing and thawing. Cryobiology. 1966:213. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mazur P., Koshimoto C. Is intracellular ice formation the cause of death of mouse sperm frozen at high cooling rates? Biol. Reprod. 2002;66:1485–1490. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod66.5.1485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Acker J.P., McGann L.E. Protective effect of intracellular ice during freezing? Cryobiology. 2003;46:197–202. doi: 10.1016/s0011-2240(03)00025-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Acker J.P., McGann L.E. Innocuous intracellular ice improves survival of frozen cells. Cell Transplant. 2002;11:563–571. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sinclair B.J., Renault D. Intracellular ice formation in insects: unresolved after 50 years? Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 2010;155:14–18. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2009.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhurova M., Woods E.J., Acker J.P. Intracellular ice formation in confluent monolayers of human dental stem cells and membrane damage. Cryobiology. 2010;61:133–141. doi: 10.1016/j.cryobiol.2010.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Muldrew K., McGann L.E. Mechanisms of intracellular ice formation. Biophys. J. 1990;57:525–532. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(90)82568-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Avetisyan A., Jensen J.B., Huser T. Monitoring trehalose uptake and conversion by single bacteria using laser tweezers Raman spectroscopy. Anal. Chem. 2013;85:7264–7270. doi: 10.1021/ac4011638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.De Veij M., Vandenabeele P., Moens L. Reference database of Raman spectra of pharmaceutical excipients. J. Raman Spectrosc. 2009;40:297–307. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Martens W.N., Frost R.L., Theo Kloprogge J. Raman spectroscopy of dimethyl sulphoxide and deuterated dimethyl sulphoxide at 298 and 77 K. J. Raman Spectrosc. 2002;33:84–91. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Koenig J.L. Raman spectroscopy of biological molecules: a review. J. Polym. Sci. Macromol. Rev. 1972;6:59–177. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brazhe N.A., Treiman M., Sosnovtseva O.V. Mapping of redox state of mitochondrial cytochromes in live cardiomyocytes using Raman microspectroscopy. PLoS One. 2012;7:e41990. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0041990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.