Abstract

The directed migration (chemotaxis) of neutrophils toward the bacterial peptide N-formyl-Met-Leu-Phe (fMLP) is a crucial process in immune defense against invading bacteria. While navigating through a gradient of increasing concentrations of fMLP, neutrophils and neutrophil-like HL-60 cells switch from exhibiting directional migration at low fMLP concentrations to exhibiting circuitous migration at high fMLP concentrations. The extracellular signal–regulated kinase (ERK) pathway is implicated in balancing this fMLP concentration–dependent switch in migration modes. We investigated the role and regulation of ERK signaling through single-cell analysis of neutrophil migration in response to different fMLP concentrations over time. We found that ERK exhibited gradated, rather than all-or-none, responses to fMLP concentration. Maximal ERK activation occurred in response to about 100 nM fMLP, and ERK inactivation was promoted by p38. Furthermore, we found that directional migration of neutrophils reached a maximal extent at about 100 nM fMLP and that ERK, but not p38, was required for neutrophil migration. Thus, our data suggest that, in chemo-tactic neutrophils responding to fMLP, ERK displays gradated activation and p38-dependent inhibition and that these ERK dynamics promote neutrophil migration.

INTRODUCTION

The chemotaxis (directed migration) of neutrophils toward the bacterial peptide N-formyl-Met-Leu-Phe (fMLP) is a crucial process in the response of the immune system to target invading bacteria. While they navigate through a gradient of increasing concentrations of fMLP, neutrophils switch from directional migration at low fMLP concentrations to circuitous migration at high fMLP concentrations (1). The mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) extracellular signal–regulated kinase 1 (ERK1) and ERK2 (collectively referred to as ERK) are implicated in switching fMLP concentration–dependent migration from directional to circuitous (1); however, the regulation and role of ERK in chemotactic neutrophils remain unclear.

Although it has long been established that ERK and the MAPK p38 are activated downstream of the binding of fMLP to its receptors formyl peptide receptor 1 (FPR1) and FPR2 (2–4), ERK was reported to display an all-or-none, “plateaued” activation profile (1) in response to increasing concentrations (50 to 1000 nM) of fMLP. Such plateaued behavior could be due to an all-or-none activation of the protein or to the saturation of the input signal. Here, we conducted single-cell analysis across time and fMLP concentration to explore this apparent concentration independence. We found that ERK exhibited gradated, rather than all-or-none, responses to fMLP concentration and that maximal ERK activation occurred at about 100 nM fMLP.

Controversy has further arisen over whether ERKs are necessary for (5, 6) or inhibit (1) neutrophil migration. Here, we used the selective inhibitors PD0325901 [MEK (MAPK kinase)] (7) and SCH772984 (ERK) (8) to demonstrate that ERK was required for neutrophil migration. In addition, in experiments with the p38-specific inhibitors VX-702 and BIRB-796, we showed that p38 modulated the response of ERK to fMLP and that p38 inhibited directional migration. Together, our work suggests that (i) neutrophil chemotaxis toward fMLP peaks at about 100 nM fMLP, (ii) fMLP activates ERK through gradated and concentration-dependent responses with maximal activity occurring in response to 100 nM fMLP, (iii) p38 mediates the inhibition of ERK activity toward basal activity, and (iv) ERK supports, whereas p38 inhibits, neutrophil chemotaxis toward fMLP.

RESULTS

Neutrophil chemotaxis reaches a maximal extent at 100 nM fMLP

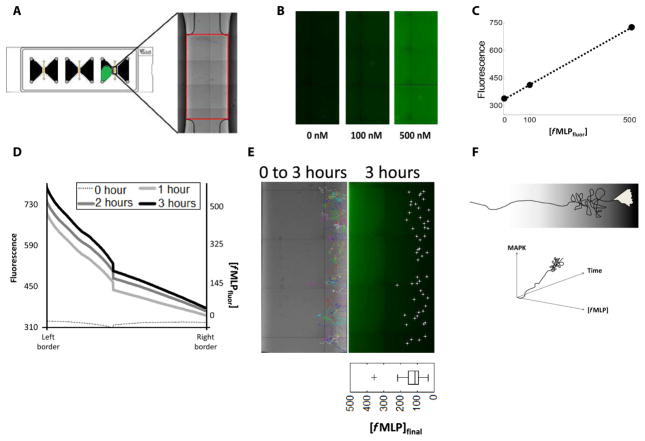

Neutrophils and neutrophil-like HL-60 cells cannot complete migration through steep gradients of fMLP (500 and 1000 nM, respectively) (1); however, the concentration of fMLP at which neutrophils and HL-60 cells cease directional migration is unknown. To answer this question, we visualized a gradient of a labeled fMLP derivative, fluorescein-formyl-Nle-Leu-Phe-Nle-Tyr-Lys (fMLPfluor) (Fig. 1A and fig. S1). Known concentrations of the probe were imaged (Fig. 1B) to relate fluorescence to concentration (Fig. 1C). A gradient of 0 to 500 nM fMLPfluor across the observation chamber was then visualized over several hours and quantified (Fig. 1D and fig. S1A). Tracks from microscopy videos of cells migrating in gradients of fMLP were overlaid on the visualized gradient of fMLPfluor (Fig. 1E) using the distinctive ends of the observation area as fiducials (Fig. 1A). We found that human neutrophils (movie S1) and HL-60 cells (movie S4) ceased directional migration well within the 3-hour interval of live-cell imaging and that the concentration of fMLP at which they began to exhibit circuitous migration was at about 100 nM fMLP (Fig. 1E and fig. S1B). Therefore, directional migration of chemotactic neutrophils reaches a maximal extent at about 100 nM fMLP.

Fig. 1. Overview of gradient characterization.

(A) Sterile microfluidic devices were used to visualize the chemoattractant gradient. Red box, region of interest identified within each chamber using the distinctive ends of the observation area as fiducials. (B) Known concentrations of the labeled fMLP derivative fMLPfluor were imaged. (C) Plot of the concentration of fMLPfluor versus fluorescence intensity from the images shown in (B). (D) A gradient of 0 to 500 nM fMLPfluor was characterized by both its fluorescence and concentration across the observation area of the device over the indicated times. Data are representative of three experiments. (E) Tracks (multicolored, left) were created from 3-hour microscopy videos of cells migrating in a gradient of 0 to 500 nM fMLP. The end points of each track at 3 hours (white dots, right) were overlaid on the visualized gradient of fMLPfluor using the distinctive ends of the observation area as fiducials. Images are representative of three experiments. Bottom right: Boxplot contains data combined from three experiments. (F) Studies of chemotaxis within a gradient are confounded by the fact that both the parameters of chemoattractant concentration and time vary as the cell migrates.

ERK has gradated responses to fMLP concentration and exhibits a concentration-dependent inactivation

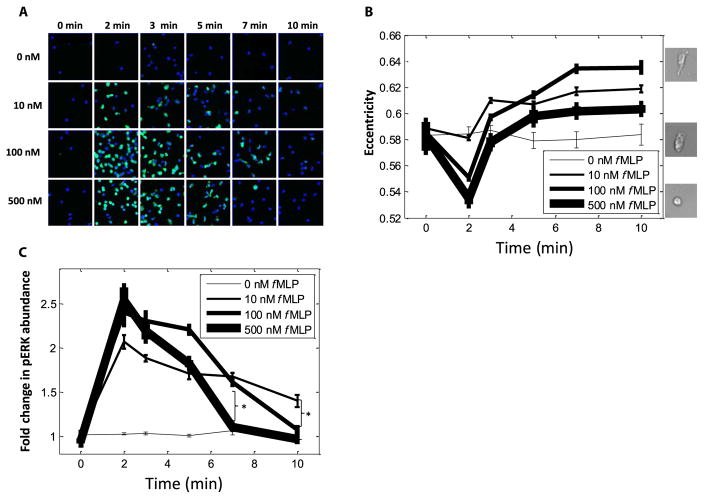

What happens to ERK and p38 dynamics at this transition point of 100 nM fMLP? A confounding factor in studying neutrophil chemotaxis within a gradient is that both the parameters of chemoattractant concentration and time vary as a cell migrates (Fig. 1F). To disentangle these two variables, we next exposed the cells to a range of uniform concentrations of fMLP and observed the consequences of this stimulation at various times between 0 and 10 min (Fig. 2A and fig. S2A). Concentrations of 10, 100, and 500 nM fMLP were chosen on the basis of the earlier result that cells lose directionality at about 100 nM fMLP and the fact that FPR1 and FPR2 have dissociation constants of 10 and ~500 nM fMLP, respectively (9). We validated our 10-min time frame by observing the response of morphological polarity; consistent with previous studies (10, 11), the morphological polarity of the cells plateaued within this time frame (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2. Changes in morphology, but not ERK activation, in migrating cells terminate within 10 min.

(A) Cells (168,837) were incubated for the indicated times in the presence of the indicated concentrations of fMLP (with at least 1790 cells per condition) before they were fixed, incubated with fluorescent antibodies against pERK, and then imaged. Each frame is representative of 36 frames per well, and four replicate wells per condition were analyzed. (B) Analysis of cell morphology (eccentricity) in 168,837 cells exposed to the indicated concentrations of fMLP over time (with at least 1790 cells per condition). Data are means ± SEM of at least 1790 cells from four replicates. Right: Images show representative cells with high (top, 100 nM fMLP at 10 min), basal (0 nM fMLP at 10 min), and low (bottom, 500 nM fMLP at 2 min) eccentricity. (C) Analysis of the fold change in pERK fluorescence in 168,837 cells exposed to the indicated concentrations of fMLP over time (with at least 1790 cells per condition). Data are means ± SEM of at least 1790 cells from four replicate experiments. *P < 0.05 compared to controls by two-sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov test.

We first asked whether ERK was activated in an all-or-none, ultrasensitive response (12, 13), as was seen in certain other biological systems. For example, in maturing Xenopus laevis oocytes (13), cells switch between having no ERK activation and complete ERK activation, and no intermediate ERK responses are observed. ERK in chemotactic neutrophils has been characterized as having a plateaued activation curve (1). Therefore, we measured the amounts of phosphorylated ERK (pERK) to determine the responses of individual cells within our various uniform fMLP concentrations (0 to 500 nM) and at various time points (0 to 10 min). Histograms summarizing the cell behaviors (fig. S2B) revealed that ERK displayed a gradated rather than an all-or-none activation by fMLP in chemotactic neutrophils.

Response curves to each fMLP concentration across time (Fig. 2C) further supported a model of gradated ERK activation, because maximal pERK abundance in cells exposed to 10 nM fMLP was less than that in cells exposed to higher concentrations of fMLP. However, and consistent with the saturation seen in our migration data (Fig. 1E), ERK phosphorylation was maximal at 100 nM fMLP (Fig. 2C); that is, the amount of pERK detected in response to stimulation with 500 nM fMLP was the same as that measured in cells exposed to 100 nM fMLP (1). We additionally noticed an fMLP concentration dependence in the loss of pERK abundance. Note that the ERK response curves for the three concentrations of fMLP became separated at 10 min and were reverse-ordered by concentration (Fig. 2C and fig. S2C). That is, the abundance of pERK returned to basal amounts within the 10-min time frame only in those cells stimulated with 500 nM fMLP. The response to 100 nM fMLP appeared to be intermediate, with statistically significant separation from the response to 10 nM fMLP by 10 min and from the response to 500 nM by 7 min and continuing this trend at 10 min. This phenotype of an fMLP concentration–dependent loss of signaling was not common among the MAPKs, because costaining images for phosphorylated p38 (pp38) showed that p38 activation similarly peaked at 2 min after stimulation with fMLP but that p38 response curves for all three concentrations of fMLP fell sharply past the baseline and did not significantly separate from one another (fig. S3, A to D). Thus, our data indicate that ERK is activated in gradated responses to fMLP, with maximal activation at 100 nM fMLP and then a concentration-dependent loss of activity that is centered on 100 nM fMLP.

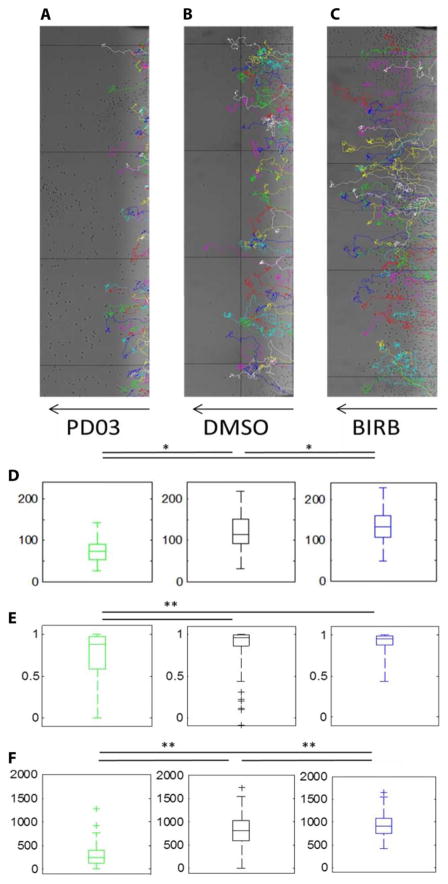

ERK promotes, whereas p38 inhibits, neutrophil migration toward fMLP

ERK and p38 have been characterized as “stop” and “go” signals in neutrophil chemotaxis based on migration experiments with the inhibitors PD98059 and SB203580 (1). Because the MEK inhibitor PD98059 depletes cellular calcium (7), we assessed the migration of neutrophils treated with PD0325901, a MEK inhibitor of greater selectivity (Fig. 3 and fig. S4) (7). PD0325901 caused an early and abrupt cessation of the migration of human neutrophils (Fig. 3, A and D, and movie S2) as compared to that of the dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO)–treated control cells (Fig. 3, B and D, and movie S1). We further replicated these results in experiments with HL-60 cells in which we compared the migration of cells treated with DMSO (fig. S4A and movie S4) to that of cells treated with either PD0325901 or the ERK inhibitor SCH772984 (fig. S4, B, C, and F, and movies S5 and S6). Consistent with previous work (1), we found that the p38 inhibitor SB203580 also caused early cessation of the directional migration of human neutrophils (fig. S4, D and F, and movie S7). However, SB203580 has several off-target effects (14), including the inhibition of Raf (15) and therefore of ERK itself (fig. S5, A to C). Therefore, we also assessed the migration of human neutrophils (Fig. 3, C and D, and movie S3) and HL-60 cells (fig. S4, E and F, and movie S8) treated with the more selective p38 inhibitor BIRB-796 (14, 16–20). Unexpectedly, neutrophils treated with BIRB-796 migrated substantially farther up the gradient than did cells treated with DMSO (Fig. 3, C and D, and movie S3).

Fig. 3. ERK promotes, but p38 inhibits, neutrophil migration toward fMLP.

(A to C) Representative migration tracks (multicolored) of human neutrophils treated with 100 nM PD0325901 (A), DMSO (B), or 10 nM BIRB-796 (C) and then allowed to migrate across a gradient of 0 to 500 nM fMLP (indicated by the arrows). (D to F) Quantification of final fMLP concentration (D), chemotactic index (E), and the total distance of the migration tracks (F) of human neutrophils from the experiments shown in (A) to (C), with three replicate experiments combined within each boxplot. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 when compared to controls by two-sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov test.

Further quantification demonstrated that this increased migration of BIRB-796–treated neutrophils was not due to improved chemotactic efficiency (Fig. 3E). Consistent with previous findings from experiments with p38-specific RNA interference (1), BIRB-796–treated neutrophils initially showed a worsened chemotactic index at 30 min of migration (fig. S4G). However, over the course of a 3-hour time frame, which is characteristic of neutrophil influx toward a site of bacterial infection (21) or sterile injury (22), the chemotactic index was unchanged between DMSO-treated and BIRB-796–treated neutrophils (fig. S4G). Rather, we found that BIRB-796–treated neutrophils showed an increased displacement vector up the gradient of fMLP, because they migrated an increased total distance within the 3-hour time frame (Fig. 3F). Together, our data suggest that ERK promotes, whereas p38 inhibits, neutrophil migration up an fMLP gradient and that p38 appears to inhibit neutrophil migration by limiting the total distance (as compared to the displacement) traveled by the cell.

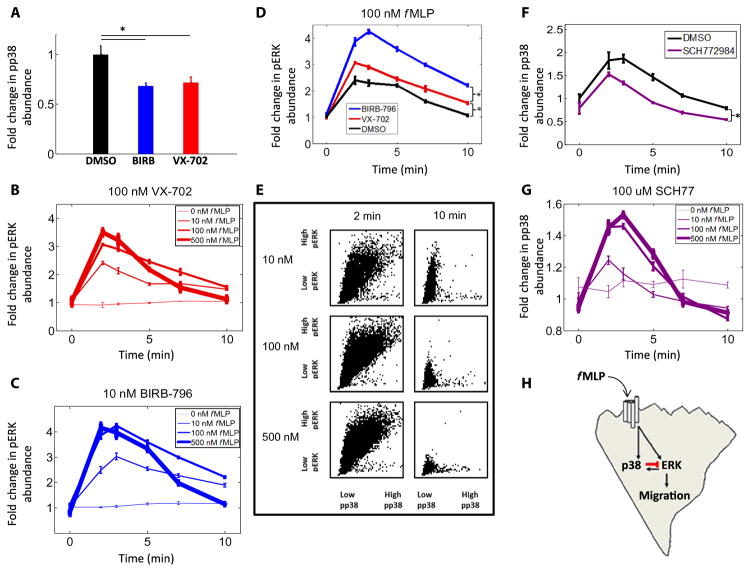

p38 decreases the sensitivity of ERK to fMLP

FPR1 is phosphorylated by p38 (1). To ask whether p38 in turn altered the signaling from FPR1 to ERK, we stimulated p38-inhibited cells (Fig. 4A) with uniform concentrations of fMLP before fixation at various time points between 0 and 10 min (fig. S5). Under these conditions, we found that the ERK response curve for 100 nM fMLP no longer fell below that for 10 nM fMLP (Fig. 4, B and C). The ERK responses to 10 and 100 nM fMLP were indistinguishable at 10 min in VX-702–treated cells (Fig. 4B and fig. S5D). The ERK response curve to 100 nM fMLP was greater than that to 10 nM fMLP in BIRB-796–treated cells (Fig. 4C and fig. S5E). This slower inactivation in the BIRB-796–treated cells may reflect the ability of BIRB-796 to inhibit p38δ, which is the most abundant p38 isoform in neutrophils (23), and inhibits ERK in other systems (24). That BIRB-796 and VX-702 did not change the basal amounts of pERK compared to those in DMSO-treated, control cells (fig. S5F) enabled comparison of the response curves to 100 nM fMLP as normalized by fold change. This analysis revealed that both p38 inhibitors caused sustained ERK activation at 10 min (Fig. 4D), which suggests that there may be time-varying network effects (10), and that p38 may inhibit fMLP-stimulated ERK activation specifically at late times (10 min).

Fig. 4. ERK activity is inhibited by p38 at late time points.

(A) Measurement of the fold change in pp38 fluorescence intensity in cells treated with DMSO (15,179 cells), BIRB-796 (14,990 cells), or VX-702 (15,653 cells) and incubated for 3 min in 100 nM fMLP. Data are means ± SEM of four replicate experiments. *P < 0.05 compared to controls by two-sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. (B and C) Analysis of pERK fluorescence intensity in cells treated with VX-702 (139,489 cells) (B) or BIRB-796 (124,223 cells) (C) and then exposed to the indicated concentrations of fMLP over time. Data are means ± SEM of four replicate experiments (with at least 502 cells per condition). (D) Analysis of pERK fluorescence intensity in cells treated with DMSO (54,565 cells), VX-702 (41,219 cells), or BIRB-796 (41,186 cells) before they were incubated in 100 nM fMLP for the indicated times. Data are means ± SEM of four replicate experiments (with at least 1009 cells per condition). (E) Cells (63,661) treated with DMSO and exposed to the indicated concentrations of fMLP were analyzed by quantitative immunofluorescence to determine the staining intensities of pERK and pp38 in each individual cell. Each cell was then plotted as a single dot in a scatterplot of the relative abundances of pERK and pp38. Data are pooled from four replicate experiments, with at least 2491 cells per condition. *P < 0.05 compared to controls by two-sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. (F) Measurement of the fold change in pp38 fluorescence intensity in cells treated with DMSO (64,290 cells) or SCH772984 (68,906 cells) and then incubated in 100 nM fMLP over time. Data are means ± SEM of four replicate experiments (with at least 1355 cells per condition). *P < 0.05 compared to controls by two-sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. (G) Measurement of the fold change in pp38 fluorescence intensity in 164,199 cells treated with 100 μM SCH77 and then incubated in the indicated concentrations of fMLP over time. Data are means ± SEM of four replicate experiments (with at least 3105 cells per condition). (H) Working model in which p38 inhibits ERK activation, ERK activates p38, and ERK drives neutrophil migration in response to the stimulation of FPRs by fMLP. The inhibitory interaction between p38 and ERK that occurs at late time points is shown in red.

To search for this trend within time-dependent fluctuations in phosphorylation states, we plotted costained cells treated with fMLP over time by their pERK and pp38 intensities. We found that pp38 and pERK displayed covariation at the peak time of 2 min, filling the upper right quadrant of the plots (Fig. 4E, left). However, and consistent with our inhibitor data, we found that the cells with the greatest amount of pERK at late times (10 min) had the least amount of pp38 (Fig. 4E, right). Although p38 and ERK were previously reported not to alter one another’s activation by fMLP (1), this conclusion was based on data from a single time point of 2 min. Our drug and covariation data suggest that, across a broader time course, p38 appears to inhibit ERK activation, although it is unclear whether this inhibition occurs through protein phosphatase 2A, as occurs in other systems (25), or at a different signaling level.

Meanwhile, ERK did not appear to reciprocate this inhibition; SCH772984-treated cells demonstrated statistically significantly decreased, rather than increased, p38 activation in response to 100 nM fMLP as compared to that in DMSO-treated control cells on the same plate (Fig. 4F). In a separate experiment, p38 response curves for all concentrations of fMLP (10, 100, and 500 nM) in SCH772984-treated cells (Fig. 4G) demonstrated similar decay patterns to those seen in DMSO-treated control cells (fig. S3D). Thus, ERK increased the extent of phosphorylation of p38 in a basal, non–time-dependent manner. Together, our data suggest a model in which ERK promotes fMLP-directed neutrophil migration and p38 activation, whereas p38 tunes ERK activation back to baseline and thus inhibits fMLP-directed neutrophil migration (Fig. 4H).

DISCUSSION

Upon exposure to fMLP, a neutrophil will break its symmetry, establishing a polarized front and back, and begin migration. Although the molecular underpinnings of this initial cell polarization and directional sensing have been extensively characterized (26–28), it is less clear what signals are important for the behavior of neutrophils once they have migrated into areas of high concentrations of fMLP. Here, we interrogated these molecular players with an array of selective inhibitors and in the context of a characterized linear gradient. Our results demonstrate that neutrophil migration saturated at about 100 nM fMLP (Fig. 1E) and that ERK, but not p38, demonstrated an fMLP concentration dependence (transitioning around 100 nM fMLP) in the loss of activity toward baseline after an initial peak (Fig. 2C and fig. S2). ERKs were activated in gradated responses (fig. S2C), which were required for the migration of chemotactic neutrophils, because cells treated with the MEK inhibitor PD0325901 or the ERK inhibitor SCH772984 failed to migrate into an fMLP gradient (Fig. 3, A and D, and fig. S4, B, C, and F).

These findings are consistent with other reports that ERK is necessary for adhesion and migration (6, 29, 30), but contradict the model of p38 as a go signal and ERK as a stop signal for chemotactic neutrophils (1) moving within an fMLP gradient. Instead, we found in experiments with BIRB-796, which has high specificity for p38 and blocks multiple isoforms of p38 (14), that p38 inhibited neutrophil migration up a gradient of fMLP (Fig. 3, C to F). Finally, we showed in uniform field stimulation assays that p38 inhibited the fMLP-stimulated activation of ERK at later time points. Thus, our data suggest that in chemotactic neutrophils (i) directional migration of neutrophils reaches a maximal extent at about 100 nM fMLP, (ii) fMLP activates ERK in gradated and concentration-dependent responses, with maximal activation achieved at 100 nM fMLP, (iii) p38 modulates the inactivation of ERK back toward baseline, and (iv) ERK promotes fMLP-directed migration (5, 31), whereas p38 inhibits ERK activation and therefore inhibits fMLP-directed neutrophil migration.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Isolation of human neutrophils

Blood was collected from a healthy human donor and subjected to a standard neutrophil isolation protocol (32) of density gradient separation with Lympholyte-poly(R) (Cedarlane Laboratories) and purification with Red Cell Lysis Buffer (Roche Group). All isolation steps were performed under sterile conditions to avoid activation of the neutrophils. The neutrophil medium was composed of serum-free RPMI 1640 medium containing L-glutamine, 25 mM Hepes, and 2% human serum albumin.

Cells and cell culture

HL-60 cells were cultured as previously described (33). Briefly, the cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium containing L-glutamine and 25 mM Hepes supplemented with antibiotic-antimycotic (Invitrogen) and 10% fetal bovine serum (HyClone) in an incubator at 37°C and 5% CO2. Cell differentiation was induced by adding DMSO (endotoxin-free, hybridoma-tested; D2650, Sigma) to the medium at a final concentration of 1.3%. For all experiments, cells were used at 5 days after the initiation of differentiation. Before the cells were used, they were washed and resuspended in serum-free RPMI 1640 containing L-glutamine, 25 mM Hepes, and 0.1% human serum albumin.

Gradient migration assays

Live cells were imaged within an fMLP gradient generated by a sterile μ-Slide Chemotaxis3D microfluidic device (ibidi, 80326) coated with fibronectin (50 μg/ml). Cells were washed and resuspended in serum-free medium, as described earlier, in which the drug (10 μM SB203580, 10 nM BIRB-796, 100 nM VX-702, 100 nM PD0325901, or 100 nM SCH772984) or vehicle (DMSO) was dissolved. Each cell suspension of about 1 × 106 cells/ml was then seeded into the observation area and the right reservoir of a chamber within the ibidi μ-Slide Chemotaxis3D microfluidic device. After 2 hours of incubation in an incubator at 37°C and 5% CO2, the chambers were carefully flushed with serum-free medium, with their respective drug dilutions. A gradient with a maximum value of 500 nM fMLP was generated across the observation area of each chamber by gently pipetting chemoattractant into the left reservoirs in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. The cells were immediately imaged in a heated chamber for 3 hours. Montage images of the entire observation area were recorded with a BD Pathway 855 Bioimager (BD Biosciences) equipped with a laser autofocus system, an Olympus 10× objective lens, and a high-resolution Hamamatsu ORCA ER charge-coupled device camera. Image acquisition was controlled by AttoVision version 1.5 software (BD Biosciences). Cell tracks were then identified in ImageJ software (34) with the Manual Tracking plugin. The end points of cell tracks were overlaid on an image of a 500 nM gradient of fluorescein-conjugated formyl-Nle-Leu-Phe-Nle-Tyr-Lys (Invitrogen) using the distinctive ends of the observation chambers as fiducials. Further quantification of tracks was performed with custom-written MATLAB code. The total distance traveled by each cell was calculated by adding the incremental distance traveled (irrespective of direction) from frame to frame for each individual track. Chemotactic index was calculated as CI = (AO − BO)/AB (35), where AB is the length of the vector from the beginning to the end of a track, and AO − BO is the component of AB that is parallel to the direction of the gradient.

Uniform field stimulation assays

Similar to the gradient migration assays, cells were washed and re-suspended at about 1 × 106 cells/ml in serum-free medium in which the drug (10 μM SB203580, 10 nM BIRB-796, 100 nM VX-702, 100 nM PD0325901, or 100 nM SCH772984) or vehicle (DMSO) was dissolved. Cells were plated onto 96-well Nunc glass plates (Thermo Scientific, 164588) coated with fibronectin (100 μg/ml). After 2 hours of incubation in an incubator at 37°C and 5% CO2, the wells were uniformly stimulated with fMLP (dissolved in the appropriate drug-containing solutions) before undergoing formaldehyde fixation at the times specified in the figure legends. Immunofluorescent staining was then performed as previously described (10, 11), with antibodies against pERK (Thr202/Tyr204) (Cell Signaling Technology, 9101) and pp38 (Thr180/Tyr182) (Abcam, ab45381). Fluorescence images were acquired on a BD Pathway 855 Bioimager (BD Biosciences) with an Olympus 20× objective lens. Cellular features, including cell-averaged signal intensity and eccentricity, were extracted with CellProfiler software (36). These data were plotted as response curves, histograms, three-dimensional (3D) surface plots, and scatterplots with custom-written MATLAB code. The 3D surface plots were generated with MATLAB using the surf function with standard interpolation presets and with a log10 scale for the fMLP concentration axis.

Statistical analysis

Statistical significance was assessed with the two-sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Supplementary Material

Movie S1. DMSO-treated human neutrophils migrating in a gradient of 0 to 500 nM fMLP.

Movie S2. PD0325901-treated human neutrophils migrating in a gradient of 0 to 500 nM fMLP.

Movie S3. BIRB-796–treated human neutrophils migrating in a gradient of 0 to 500 nM fMLP.

Movie S4. DMSO-treated control HL-60 cells migrating in a gradient of 0 to 500 nM fMLP.

Movie S5. PD0325901-treated HL-60 cells migrating in a gradient of 0 to 500 nM fMLP.

Movie S6. SCH772984-treated HL-60 cells migrating in a gradient of 0 to 500 nM fMLP.

Movie S7. SB203580-treated HL-60 cells migrating in a gradient of 0 to 500 nM fMLP.

Movie S8. BIRB-796–treated HL-60 cells migrating in a gradient of 0 to 500 nM fMLP.

Fig. S1. Migration of cells across a linear gradient of fMLP.

Fig. S2. ERK activation remains increased in cells responding to 10 nM fMLP.

Fig. S3. The abundance of pp38 is reduced below basal amounts within 10 min of fMLP stimulation.

Fig. S4. ERK promotes, whereas p38 inhibits, the migration of neutrophils toward fMLP.

Fig. S5. Inhibition of p38 results in increased pERK abundance in neutrophils at late times after exposure to 10 or 100 nM fMLP.

Acknowledgments

We thank C. Wichaidit for helpful discussions, A. Whitehurst and C. Thorne for critical review of the manuscript, and D. Ware for administrative assistance.

Funding: The work was supported by grants from the NIH to M.H.C. (R37DK34128), S.J.A. (R01GM112690 and R01GM071794), and L.F.W. (CA185404 and CA184984), and the Welch Foundation to M.H.C. (I-1243), S.J.A. (I-1619), and L.F.W. (I-1644). E.R.Z. was also supported by the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Scientist Training Program.

Footnotes

Author contributions: E.R.Z. performed and analyzed the experiments and wrote the manuscript with advice from all authors. S.L. performed the experiments. M.H.C. designed and guided the gradient experiments. S.J.A., L.F.W., and M.H.C. designed the uniform field experiments, provided reagents, critically evaluated all results, and revised the manuscript.

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Liu X, Ma B, Malik AB, Tang H, Yang T, Sun B, Wang G, Minshall RD, Li Y, Zhao Y, Ye RD, Xu J. Bidirectional regulation of neutrophil migration by mitogen-activated protein kinases. Nat Immunol. 2012;13:457–464. doi: 10.1038/ni.2258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Downey GP, Butler JR, Tapper H, Fialkow L, Saltiel AR, Rubin BB, Grinstein S. Importance of MEK in neutrophil microbicidal responsiveness. J Immunol. 1998;160:434–443. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zu YL, Qi J, Gilchrist A, Fernandez GA, Vazquez-Abad D, Kreutzer DL, Huang CK, Sha’afi RI. p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase activation is required for human neutrophil function triggered by TNF-α or FMLP stimulation. J Immunol. 1998;160:1982–1989. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.El Benna J, Han J, Park J-W, Schmid E, Ulevitch RJ, Babior BM. Activation of p38 in stimulated human neutrophils: Phosphorylation of the oxidase component p47phox by p38 and ERK but not by JNK. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1996;334:395–400. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1996.0470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mizuno R, Kamioka Y, Kabashima K, Imajo M, Sumiyama K, Nakasho E, Ito T, Hamazaki Y, Okuchi Y, Sakai Y, Kiyokawa E, Matsuda M. In vivo imaging reveals PKA regulation of ERK activity during neutrophil recruitment to inflamed intestines. J Exp Med. 2014;211:1123–1136. doi: 10.1084/jem.20132112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ren DL, Sun AA, Li YJ, Chen M, Ge SC, Hu B. Exogenous melatonin inhibits neutrophil migration through suppression of ERK activation. J Endocrinol. 2015;227:49–60. doi: 10.1530/JOE-15-0329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wauson EM, Guerra ML, Barylko B, Albanesi JP, Cobb MH. Off-target effects of MEK inhibitors. Biochemistry. 2013;52:5164–5166. doi: 10.1021/bi4007644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morris EJ, Jha S, Restaino CR, Dayananth P, Zhu H, Cooper A, Carr D, Deng Y, Jin W, Black S, Long B, Liu J, DiNunzio E, Windsor W, Zhang R, Zhao S, Angagaw MH, Pinheiro EM, Desai J, Xiao L, Shipps G, Hruza A, Wang J, Kelly J, Paliwal S, Gao X, Babu BS, Zhu L, Daublain P, Zhang L, Lutterbach BA, Pelletier MR, Philippar U, Siliphaivanh P, Witter D, Kirschmeier P, Bishop WR, Hicklin D, Gilliland DG, Jayaraman L, Zawel L, Fawell S, Samatar AA. Discovery of a novel ERK inhibitor with activity in models of acquired resistance to BRAF and MEK inhibitors. Cancer Discov. 2013;3:742–750. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-13-0070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ye RD, Boulay F, Wang JM, Dahlgren C, Gerard C, Parmentier M, Serhan CN, Murphy PM International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. LXXIII. Nomenclature for the formyl peptide receptor (FPR) family. Pharmacol Rev. 2009;61:119–161. doi: 10.1124/pr.109.001578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ku CJ, Wang Y, Weiner OD, Altschuler SJ, Wu LF. Network crosstalk dynamically changes during neutrophil polarization. Cell. 2012;149:1073–1083. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang Y, Ku CJ, Zhang ER, Artyukhin AB, Weiner OD, Wu LF, Altschuler SJ. Identifying network motifs that buffer front-to-back signaling in polarized neutrophils. Cell Rep. 2013;3:1607–1616. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Robbins DJ, Cobb MH. Extracellular signal-regulated kinases 2 autophosphorylates on a subset of peptides phosphorylated in intact cells in response to insulin and nerve growth factor: Analysis by peptide mapping. Mol Biol Cell. 1992;3:299–308. doi: 10.1091/mbc.3.3.299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ferrell JE, Jr, Machleder EM. The biochemical basis of an all-or-none cell fate switch in Xenopus oocytes. Science. 1998;280:895–898. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5365.895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bain J, Plater L, Elliott M, Shpiro N, Hastie CJ, McLauchlan H, Klevernic I, Arthur JSC, Alessi DR, Cohen P. The selectivity of protein kinase inhibitors: A further update. Biochem J. 2007;408:297–315. doi: 10.1042/BJ20070797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hall-Jackson CA, Goedert M, Hedge P, Cohen P. Effect of SB 203580 on the activity of c-Raf in vitro and in vivo. Oncogene. 1999;18:2047–2054. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pargellis C, Tong L, Churchill L, Cirillo PF, Gilmore T, Graham AG, Grob PM, Hickey ER, Moss N, Pav S, Regan J. Inhibition of p38 MAP kinase by utilizing a novel allosteric binding site. Nat Struct Biol. 2002;9:268–272. doi: 10.1038/nsb770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Branger J, van den Blink B, Weijer S, Madwed J, Bos CL, Gupta A, Yong CL, Polmar SH, Olszyna DP, Hack CE, van Deventer SJH, Peppelenbosch MP, van der Poll T. Anti-inflammatory effects of a p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase inhibitor during human endotoxemia. J Immunol. 2002;168:4070–4077. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.8.4070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lea S, Harbron C, Khan N, Booth G, Armstrong J, Singh D. Corticosteroid insensitive alveolar macrophages from asthma patients; synergistic interaction with a p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) inhibitor. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2015;79:756–766. doi: 10.1111/bcp.12536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schreiber S, Feagan B, D’Haens G, Colombel J-F, Geboes K, Yurcov M, Isakov V, Golovenko O, Bernstein CN, Ludwig D, Winter T, Meier U, Yong C, Steffgen J BIRB 796 Study Group. Oral p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase inhibition with BIRB 796 for active Crohn’s disease: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:325–334. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2005.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Branger J, van den Blink B, Weijer S, Gupta A, van Deventer SJH, Hack CE, Peppelenbosch MP, van der Poll T. Inhibition of coagulation, fibrinolysis, and endothelial cell activation by a p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase inhibitor during human endotoxemia. Blood. 2003;101:4446–4448. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-11-3338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lämmermann T, Afonso PV, Angermann BR, Wang JM, Kastenmüller W, Parent CA, Germain RN. Neutrophil swarms require LTB4 and integrins at sites of cell death in vivo. Nature. 2013;498:371–375. doi: 10.1038/nature12175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McDonald B, Pittman K, Menezes GB, Hirota SA, Slaba I, Waterhouse CCM, Beck PL, Muruve DA, Kubes P. Intravascular danger signals guide neutrophils to sites of sterile inflammation. Science. 2010;330:362–366. doi: 10.1126/science.1195491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Korb A, Tohidast-Akrad M, Cetin E, Axmann R, Smolen J, Schett G. Differential tissue expression and activation of p38 MAPK α, β, γ, and δ isoforms in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:2745–2756. doi: 10.1002/art.22080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Efimova T, Broome AM, Eckert RL. A regulatory role for p38δ MAPK in keratinocyte differentiation. Evidence for p38δ-ERK1/2 complex formation. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:34277–34285. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302759200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mistafa O, Ghalali A, Kadekar S, Högberg J, Stenius U. Purinergic receptor-mediated rapid depletion of nuclear phosphorylated Akt depends on pleckstrin homology domain leucine-rich repeat phosphatase, calcineurin, protein phosphatase 2A, and PTEN phosphatases. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:27900–27910. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.117093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xu J, Wang F, Van Keymeulen A, Herzmark P, Straight A, Kelly K, Takuwa Y, Sugimoto N, Mitchison T, Bourne HR. Divergent signals and cytoskeletal assemblies regulate self-organizing polarity in neutrophils. Cell. 2003;114:201–214. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00555-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Devreotes PN, Zigmond SH. Chemotaxis in eukaryotic cells: A focus on leukocytes and Dictyostelium. Annu Rev Cell Biol. 1988;4:649–686. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.04.110188.003245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Srinivasan S, Wang F, Glavas S, Ott A, Hofmann F, Aktories K, Kalman D, Bourne HR. Rac and Cdc42 play distinct roles in regulating PI(3,4,5)P3 and polarity during neutrophil chemotaxis. J Cell Biol. 2003;160:375–385. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200208179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Capodici C, Pillinger MH, Han G, Philips MR, Weissmann G. Integrin-dependent homotypic adhesion of neutrophils. Arachidonic acid activates Raf-1/Mek/Erk via a 5-lipoxygenase-dependent pathway. J Clin Invest. 1998;102:165–175. doi: 10.1172/JCI592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pillinger MH, Feoktistov AS, Capodici C, Solitar B, Levy J, Oei TT, Philips MR. Mitogen-activated protein kinase in neutrophils and enucleate neutrophil cytoplasts: Evidence for regulation of cell-cell adhesion. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:12049–12056. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.20.12049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mendoza MC, Er EE, Zhang W, Ballif BA, Elliott HL, Danuser G, Blenis J. ERK-MAPK drives lamellipodia protrusion by activating the WAVE2 regulatory complex. Mol Cell. 2011;41:661–671. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.02.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oh H, Siano B, Diamond S. Neutrophil isolation protocol. J Visualized Exp. 2008;17:e745. doi: 10.3791/745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Loo L-H, Lin H-J, Steininger RJ, III, Wang Y, Wu LF, Altschuler SJ. An approach for extensibly profiling the molecular states of cellular subpopulations. Nat Methods. 2009;6:759–765. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schneider CA, Rasband WS, Eliceiri KW. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat Methods. 2012;9:671–675. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xu J, Wang F, Van Keymeulen A, Rentel M, Bourne HR. Neutrophil microtubules suppress polarity and enhance directional migration. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:6884–6889. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502106102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Carpenter AE, Jones TR, Lamprecht MR, Clarke C, Kang IH, Friman O, Guertin DA, Chang JH, Lindquist RA, Moffat J, Golland P, Sabatini DM. CellProfiler: Image analysis software for identifying and quantifying cell phenotypes. Genome Biol. 2006;7:R100. doi: 10.1186/gb-2006-7-10-r100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Movie S1. DMSO-treated human neutrophils migrating in a gradient of 0 to 500 nM fMLP.

Movie S2. PD0325901-treated human neutrophils migrating in a gradient of 0 to 500 nM fMLP.

Movie S3. BIRB-796–treated human neutrophils migrating in a gradient of 0 to 500 nM fMLP.

Movie S4. DMSO-treated control HL-60 cells migrating in a gradient of 0 to 500 nM fMLP.

Movie S5. PD0325901-treated HL-60 cells migrating in a gradient of 0 to 500 nM fMLP.

Movie S6. SCH772984-treated HL-60 cells migrating in a gradient of 0 to 500 nM fMLP.

Movie S7. SB203580-treated HL-60 cells migrating in a gradient of 0 to 500 nM fMLP.

Movie S8. BIRB-796–treated HL-60 cells migrating in a gradient of 0 to 500 nM fMLP.

Fig. S1. Migration of cells across a linear gradient of fMLP.

Fig. S2. ERK activation remains increased in cells responding to 10 nM fMLP.

Fig. S3. The abundance of pp38 is reduced below basal amounts within 10 min of fMLP stimulation.

Fig. S4. ERK promotes, whereas p38 inhibits, the migration of neutrophils toward fMLP.

Fig. S5. Inhibition of p38 results in increased pERK abundance in neutrophils at late times after exposure to 10 or 100 nM fMLP.