Abstract

BACKGROUND

Measures of contraceptive effectiveness combine technology and user-related factors. Observational studies show higher effectiveness of long-acting reversible contraception compared with short-acting reversible contraception. Women who choose long-acting reversible contraception may differ in key ways from women who choose short-acting reversible contraception, and it may be these differences that are responsible for the high effectiveness of long-acting reversible contraception. Wider use of long-acting reversible contraception is recommended, but scientific evidence of acceptability and successful use is lacking in a population that typically opts for short-acting methods.

OBJECTIVE

The objective of the study was to reduce bias in measuring contraceptive effectiveness and better isolate the independent role that long-acting reversible contraception has in preventing unintended pregnancy relative to short-acting reversible contraception.

STUDY DESIGN

We conducted a partially randomized patient preference trial and recruited women aged 18–29 years who were seeking a short-acting method (pills or injectable). Participants who agreed to randomization were assigned to 1 of 2 categories: long-acting reversible contraception or short-acting reversible contraception. Women who declined randomization but agreed to follow-up in the observational cohort chose their preferred method. Under randomization, participants chose a specific method in the category and received it for free, whereas participants in the preference cohort paid for the contraception in their usual fashion. Participants were followed up prospectively to measure primary outcomes of method continuation and unintended pregnancy at 12 months. Kaplan-Meier techniques were used to estimate method continuation probabilities. Intent-to-treat principles were applied after method initiation for comparing incidence of unintended pregnancy. We also measured acceptability in terms of level of happiness with the products.

RESULTS

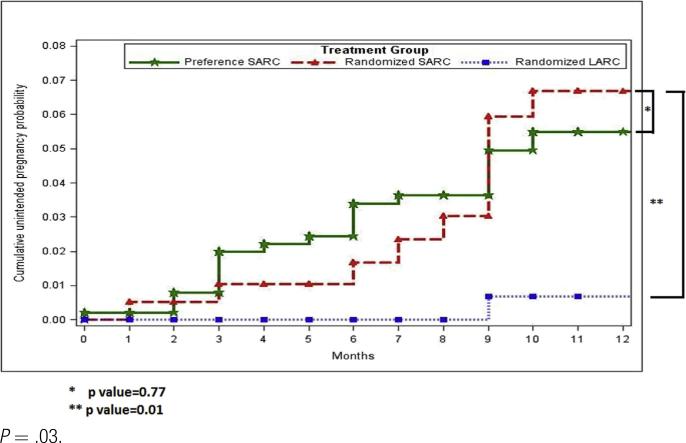

Of the 916 participants, 43% chose randomization and 57% chose the preference option. Complete loss to follow-up at 12 months was <2%. The 12 month method continuation probabilities were 63.3% (95% confidence interval, 58.9–67.3) (preference short-acting reversible contraception), 53.0% (95% confidence interval, 45.7–59.8) (randomized short-acting reversible contraception), and 77.8% (95% confidence interval, 71.0–83.2) (randomized long-acting reversible contraception) (P < .001 in the primary comparison involving randomized groups). The 12 month cumulative unintended pregnancy probabilities were 6.4% (95% confidence interval, 4.1–8.7) (preference short-acting reversible contraception), 7.7% (95% confidence interval, 3.3–12.1) (randomized short-acting reversible contraception), and 0.7% (95% confidence interval, 0.0–4.7) (randomized long-acting reversible contraception) (P = .01 when comparing randomized groups). In the secondary comparisons involving only short-acting reversible contraception users, the continuation probability was higher in the preference group compared with the randomized group (P = .04). However, the short-acting reversible contraception randomized group and short-acting reversible contraception preference group had statistically equivalent rates of unintended pregnancy (P = .77). Seventy-eight percent of randomized long-acting reversible contraception users were happy/neutral with their initial method, compared with 89% of randomized short-acting reversible contraception users (P < .05). However, among method continuers at 12 months, all groups were equally happy/neutral (>90%).

CONCLUSION

Even in a typical population of women who presented to initiate or continue short-acting reversible contraception, long-acting reversible contraception proved highly acceptable. One year after initiation, women randomized to long-acting reversible contraception had high continuation rates and consequently experienced superior protection from unintended pregnancy compared with women using short-acting reversible contraception; these findings are attributable to the initial technology and not underlying factors that often bias observational estimates of effectiveness. The similarly patterned experiences of the 2 short-acting reversible contraception cohorts provide a bridge of generalizability between the randomized group and usual-care preference group. Benefits of increased voluntary uptake of long-acting reversible contraception may extend to wider populations than previously thought.

Keywords: acceptability, adherence, contraceptive continuation, depot medroxyprogesterone acetate, intrauterine device, long-acting reversible contraception, oral contraceptives, subdermal contraceptive implant, unintended pregnancy

One of the most startling reproductive health statistics in the United States is that 48% of unintended pregnancies occur in the same month when contraception is used.1 Poor adherence, incorrect use, and/or technology failures are to blame. Although short-acting methods such as oral contraceptives provide tremendous reproductive health benefit when used consistently and correctly, they can be unforgiving. Lapses in use occur because of side effects, temporary sexual inactivity, inconvenience of resupply/redosing, and other reasons.

The largest and longest contemporary contraceptive cohort study in the United States has shown superior effectiveness of long-acting reversible contraception.2,3 The 2 types of long-acting reversible contraception are intrauterine devices and subdermal implants; once inserted, long-acting reversible contraception provides at least 3 years of continuous pregnancy protection. Long-acting reversible contraception is highly effective (>99%) because it is not subject to errors in use that often reduce effectiveness of short-acting methods.4

Whereas observational comparisons of effectiveness show superiority of long-acting reversible contraception, on average, women who choose long-acting reversible contraception may have priorities and needs vastly different from users of short-acting methods. These factors (eg, absolute and unwavering longer-term contraceptive needs) may draw women to long-acting reversible contraception and may have the same factors determining contraceptive success, regardless of technology.

General measures of contraceptive effectiveness do not separate the independent roles that technology and user-related factors may have; nevertheless, it is common to attribute effectiveness solely to the technology. Widely cited economic analyses show higher cost savings with long-acting reversible contraception compared with the short-acting methods.5,6 However, an important cost saving is from the reduction in unintended pregnancy, which can be explained in part by user characteristics and needs, not necessarily just the contraceptive technology.

Newly released prevalence data in the United States show use of short-acting methods is about 5 times higher than long-acting reversible contraception use.7 A voluntary decision to try long-acting reversible contraception (in lieu of using short-acting methods) could result in high satisfaction, avert unintended pregnancy, decrease the number of elective abortions, and provide substantial public health benefit.

Scientific evidence of long-acting reversible contraception acceptability and successful use is lacking in a population that typically opts for short-acting methods. The objective of this study is to isolate the role that long-acting reversible contraception may have in preventing unintended pregnancy in a high-risk population and to assess general satisfaction with the products.

Materials and Methods

We described the background, rationale, and enrollment results of this study in a previous publication.8 Briefly, from December 2011 to December 2013, we enrolled participants in an open-label, partially randomized patient preference trial to compare the effectiveness of short-acting reversible contraception and long-acting reversible contraception. The study was conducted at 3 health centers in North Carolina owned and operated by Planned Parenthood South Atlantic. The study was approved by the federally registered Institutional Review Board of FHI 360, the Protection of Human Subjects Committee.

Only women seeking oral contraceptives or the injectable depot medroxyprogesterone acetate were invited to participate (both new and continuing users), in order to draw from a population that often experiences unintended pregnancy and to measure the potential benefit of long-acting reversible contraception uptake with more scientific rigor. (We specifically excluded women who came to Planned Parenthood South Atlantic for long-acting reversible contraception.)

Potential participants also had to meet the following eligibility criteria: 18–29 years of age, sexually active, no previous use of an intrauterine device, no previous use of a subdermal implant, not currently pregnant or seeking a pregnancy termination on the day of screening, and good follow-up prospects (participants had to provide an e-mail address and a currently working cell phone number, and be willing to be contacted).

Clients presenting for pregnancy termination were excluded for a variety of reasons, including insufficient space to conduct study procedures on abortion clinic days and concerns from Planned Parenthood South Atlantic medical leadership that the study would make a client's visit very long and complicated and thus more stressful.

Study staff tested the e-mail address and cell phone number with potential participants during screening to verify that they worked. Women agreed to participate by signing the informed consent document. Participants received standard contraceptive information on the methods available and the out-of-pocket costs of using them.

To better estimate typical patterns of contraceptive use, we did not require any minimum duration of product use, and participants were free to switch methods or stop entirely and continue under observation. Also, we did not have mandatory follow-up clinic visits because such visits might artificially influence contraceptive use patterns.

In this trial, women started on their preferred form of contraception or elected to be randomized to either short-acting reversible contraception or long-acting reversible contraception. Randomized participants received a free long-acting reversible contraception method or free short-acting reversible contraception product for a year. Women in the preference group paid out of pocket for their contraception, had their contraception covered by private insurance, Medicaid, or the Medicaid Be Smart Family Planning Program or were able to use Title X funds (available only at 1 of 3 health centers) to cover some or all of their costs.

If randomly assigned to short-acting reversible contraception, participants chose either oral contraceptives or depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (users of depot medroxyprogesterone acetate paid injection fees to Planned Parenthood South Atlantic). If assigned to long-acting reversible contraception, participants chose 1 of the following: subdermal implant, levonorgestrel intrauterine system, or a copper intrauterine device. Long-acting reversible contraception participants were informed they could have the product removed without charge at any time and for any reason.

If participants wanted to change their short-acting reversible contraception or long-acting reversible contraception methods after starting the first dose, the replacement methods were no longer supplied by the project. For those who chose randomization and after revealing the assignment, we asked whether they had hoped for short-acting reversible contraception, long-acting reversible contraception, or assignment did not matter as long as the product was free.

For randomization, we used opaque, sealed, and sequentially ordered envelopes for each health center. Block sizes of 2, 4, and 6 were randomly assigned and within each block, and equal numbers of short-acting reversible contraception and long-acting reversible contraception assignments were generated in random order. Planned Parenthood South Atlantic staff proceeded to the randomization phase if the participant did not have further questions, agreed to be randomized, and requested that the envelope be opened. No blinding was used for any aspect of the trial.

This trial offered products currently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration and routinely available at Planned Parenthood South Atlantic:

Intrauterine device marketed in the United States as ParaGard (a T-shaped plastic device containing 380 mm2 of copper surface) with approved duration of 10 years.

Subdermal contraceptive implant, marketed in the United States as Implanon or Nexplanon (containing 68 mg of etonogestrel) with approved duration of 3 years.

Intrauterine system, marketed in the United States as Mirena (containing 52 mg of levonorgestrel) with approved duration of 5 years.

Oral contraceptives (a variety of formulations were available) requiring daily dosing.

Injectable contraceptive, containing depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (depot medroxyprogesterone acetate) with approved duration of 3 months.

Study size

To measure and compare discontinuation rates of long-acting reversible contraception and short-acting reversible contraception in different arms of the trial, we used published estimates and assumed 38% of short-acting reversible contraception users and 19% of long-acting reversible contraception users would stop using their product within a year.4 Based on our desire for 90% power to detect a 2-fold difference in the 12 month continuation rate, a 2-sided log rank test (α = .05), and an estimated 10% loss to=follow-up, we estimated that each arm (preference short-acting reversible contraception, randomized short-acting reversible contraception, randomized long-acting reversible contraception) needed 150 participants. Because we had no prior experience with partially randomized patient preference trials and did not know what proportion of women would agree to randomization, we proceeded with an abundance of caution and budgeted for 900 participants.

Follow-up data collection

If a participant returned for services, we recorded the reason for the visit and any contraceptive method provision, method switching, or long-acting reversible contraception removal. Users randomized to short-acting reversible contraception who chose oral contraceptives received 3 packs at each visit; quantities taken home by women in the preference group varied according to their individual plans and needs.

We collected data at 6 and 12 months through an online questionnaire to record contraceptive use patterns. Each participant received a $25 gift card for completing each questionnaire. Women were asked about the main reason for any method switching/discontinuation, incident pregnancies, and pregnancy plans. In the 12 month questionnaire, we asked participants about overall happiness with their initial method, whether they would ever use the method again, and whether they recommended that a friend/relative try the method; these questions were asked, even if the initial method was no longer being used.

Analysis

The primary comparisons for endpoint analyses involved the randomized cohorts: short-acting reversible contraception vs long-acting reversible contraception. Secondary comparisons examined whether short-acting reversible contraception users’ experiences (preference vs randomized cohorts) were different. We defined contraceptive discontinuation as the first significant interruption in the use of the original short-acting or long-acting product.

For oral contraceptive users, we relied primarily on self-reports. Women who stated they were no longer using pills were classified as discontinuers, as of 1 day after the self-reported last dose. Some women stated that they were still using oral contraceptives, despite long lapses in use. In these situations, we defined them as discontinuers only if 14 or more days elapsed since taking the last pill; otherwise, they were considered active users.

For depot medroxyprogesterone acetate users, we considered 106 or more days without an injection as a discontinuation event. We relied on evidence of last injection, as documented in clinic visits at Planned Parenthood South Atlantic. For participants who claimed to receive an injection outside Planned Parenthood South Atlantic, we used the self-reported date of that injection. For long-acting reversible contraception users, we used data from clinic visits and self-reports of product removal; in discrepant situations, we used Planned Parenthood South Atlantic clinic records for establishing the correct date.

We classified pregnancies as intended if the participant wanted the pregnancy at that time or sooner. Unintended pregnancies were those in which the participant stated she did not want a pregnancy at that time or ever. Pregnancies resulting in an induced abortion were classified as unintended. In most cases we used the self-reported estimated date of pregnancy; however, sometimes clinic visits provided more accurate information. This information was also used for contraceptive discontinuation events.

We used the product limit method to estimate the 12 month cumulative probabilities of method discontinuation and unintended pregnancy for the cohorts and for specific contraceptive choices within those cohorts.9 In addition, we used Cox's proportional hazards regression10 as a supporting analysis to control for the potential confounding effects that participants’ background factors may have had on the endpoints.

Proportional hazards modeling was used for the following: (1) to explore whether long-acting reversible contraception and short-acting reversible contraception differences in risks of discontinuation and unintended pregnancy were maintained in the randomized cohort and (2) to determine whether the short-acting reversible contraception experiences in the preference vs randomized cohort were indeed similar.

In the modeling exercise, we included only variables that were at least moderately associated with the cohorts (P≤.1). We used Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney tests, Fisher exact tests, or χ2 tests of association to identify any significant differences of subjects’ characteristics between the cohorts. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

For the pregnancy analysis, we applied intent-to-treat principles once the first dose was administered; thus, any unintended pregnancies after method switching or discontinuation were tallied against the first-used method. In routine care, insertion of a long-acting reversible contraception device and oral/injectable medications (short-acting reversible contraception) are not equivalent contraceptive options from a patient's perspective; thus, pure intent-to-treat principles (including those who never initiated the assigned regimen) for data analysis are not applicable in this context.

In our study, trying (initiating) a randomly assigned method tests how the contraceptive technologies fend off a variety of threats to subsequent adherence; such factors often have direct bearing on reproductive health. Our desire to measure satisfaction with long-acting reversible contraception (in a population that self-selected to short-acting reversible contraception) is also consistent with this analytical approach. Intention-to-treat analytical decisions vary considerably in published reports.11

Results

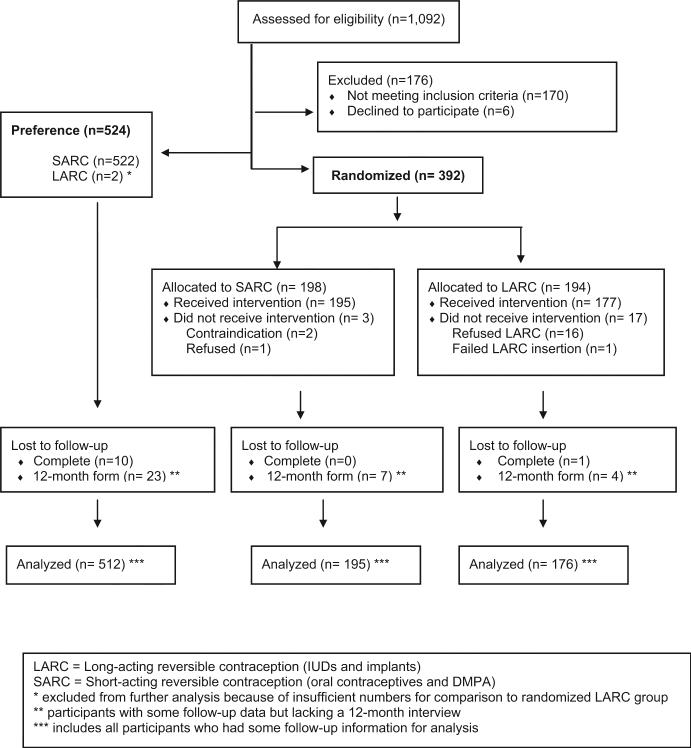

Staff at Planned Parenthood South Atlantic screened 1092 women for eligibility (Figure 1). A total of 176 subjects were excluded, mostly because of ineligibility (n = 170): poor follow-up potential (n = 46), initial stated preferences for a method other than oral contraceptives or depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (n = 36), previous long-acting reversible contraception use (n = 24), not being sexually active (n = 20), and other reasons (n = 44). Of the 916 participants who remained eligible, 57% (n = 524) chose to be in the preference cohort of the study and 43% (n = 392) asked for random assignment.

FIGURE 1.

Participant flow in study

We achieved our goal of recruiting at least 150 participants in the 3 study groups (preference short-acting reversible contraception, randomized short-acting reversible contraception, and randomized long-acting reversible contraception).

A total of 896 participants started the contraceptive regimen and formed the cohort. Those who refused to start the randomized assignment (16 of 194 in the long-acting reversible contraception group and 1 of 198 in the short-acting reversible contraception group) were discontinued from the study, and no further contact was permitted. Ninety-five percent of the cohort completed a 12 month interview. Eleven participants (1.2%) were completely lost to follow-up. Two participants chose long-acting reversible contraception in the preference cohort, but this quantity was insufficient for further analysis.

Cohort participants in the preference short-acting reversible contraception, randomized short-acting reversible contraception, and randomized long-acting reversible contraception groups were similar in terms of age, marital status, race, ethnicity, education, pregnancy history, and other variables; approximately 25% had a previous abortion (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Participant characteristics by study cohort

| Characteristic | Preference SARC (n = 522) n, %, or median (Q1–Q3) |

Randomized SARC (n = 195) n, %, or median (Q1–Q3) |

Randomized LARC (n = 177) n, %, or median (Q1–Q3) |

P valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Randomized groups | SARC groups | ||||

| Age | 23 (21–26) | 23 (21–26) | 23 (21–26) | .45 | .26 |

| Marital status | |||||

| Single | 443 (84.9) | 168 (86.2) | 149 (84.2) | .85 | .37 |

| Married | 63 (12.1) | 18 (9.2) | 18 (10.2) | ||

| Divorced/separated | 16 (3.1) | 9 (4.6) | 10 (5.6) | ||

| Months with current partner | 15 (6–36) | 11 (3–25) | 12 (4–36) | .24 | < .01 |

| Race/ethnicityb | |||||

| Hispanic | 68 (13.1) | 30 (15.4) | 14 (7.9) | .09 | .58 |

| Non-Hispanic, white | 269 (51.8) | 105 (53.8) | 111 (62.7) | ||

| Non-Hispanic, black | 124 (23.9) | 44 (22.6) | 34 (19.2) | ||

| All other single and multiple race (non-Hispanic only) | 58 (11.2) | 16 (8.2) | 18 (10.2) | ||

| Education attainment | |||||

| Not complete high school | 20 (3.8) | 7 (3.6) | 9 (5.1) | .65 | .34 |

| High school | 199 (38.1) | 82 (42.1) | 73 (41.2) | ||

| Post-high school | 102 (19.5) | 26 (13.3) | 30 (16.9) | ||

| College | 157 (30.1) | 66 (33.8) | 57 (32.2) | ||

| Graduate school | 44 (8.4) | 14 (7.2) | 8 (4.5) | ||

| Currently working | 361 (69.2) | 148 (75.9) | 136 (76.8) | .83 | .08 |

| Health insurance | |||||

| None | 189 (36.2) | 93 (47.7) | 84 (47.5) | .93 | .01 |

| Private | 266 (51) | 87 (44.6) | 76 (42.9) | ||

| Medicaid | 45 (8.6) | 7 (3.6) | 8 (4.5) | ||

| Other | 22 (4.2) | 8 (4.1) | 9 (5.1) | ||

| Reproductive health | |||||

| Previous unintended pregnancy | 134 (25.7) | 59 (30.3) | 59 (33.3) | .52 | .22 |

| Ever had an abortion | 122 (23.4) | 53 (27.2) | 53 (29.9) | .45 | .45 |

| Number of previous pregnancies | |||||

| 0 | 366 (70.1) | 123 (63.1) | 110 (62.1) | .70 | .10 |

| 1 | 95 (18.2) | 47 (24.1) | 38 (21.5) | ||

| 2 | 33 (6.3) | 14 (7.2) | 18 (10.2) | ||

| 3 or more | 28 (5.4) | 11 (5.6) | 11 (6.2) | ||

| Among those had been pregnant | |||||

| Months since last pregnancy ended | 15 (3–37) | 9 (1–23) | 10 (1–31) | .99 | .04 |

| Currently menstruating | 98 (18.8) | 34 (17.4) | 35 (19.8) | .56 | .68 |

| Wants more children | 440 (84.3) | 170 (87.2) | 136 (76.8) | < .01 | .33 |

| Months from today when pregnancy is desired | 60 (36–96) | 60 (48–96) | 60 (48–98) | .77 | .11 |

| Motivation to opt for randomization | |||||

| To receive free SARC | NA | 32 (16.4) | 9 (5.1) | < .01 | NA |

| To receive free LARC | 41 (21.0) | 67 (37.9) | |||

| To receive any free method | 122 (62.6) | 101 (57.0) | |||

Preference SARC consisted of 423 oral contraceptives users and 99 DMPA users. Randomized SARC consisted of 147 oral contraceptive users and 48 DMPA users. Randomized LARC consisted of 120 Mirena users, 6 ParaGard users, and 51 Implanon/Nexplanon users.

DMPA, depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (3 month injectable); LARC, long-acting reversible contraception; Q, quartile; SARC, short-acting reversible contraception.

For categorical variables, an exact test was used for any cell number <5, and χ2 tests was used for all cells ≥5; for continuous variables, a Wilcoxon test was used

Three participants did not report their race/ethnicity.

Nearly half of women in the randomized groups did not have health insurance, compared with 36% in the preference short-acting reversible contraception group (P < .05). The proportion of women desiring a future child in the randomized long-acting reversible contraception group (77%) was lower than the other cohorts (P < .05), although the ideal timing of a future pregnancy was similar. Participants in the preference short-acting reversible contraception group had the longest relationships with the current partner (P < .05).

In the primary comparisons among randomized participants, 12 month method continuation probabilities were 53.0% (95% confidence interval, 45.7–59.8) for short-acting reversible contraception users and 77.8% (95% confidence interval, 70.9–83.2) for long-acting reversible contraception users (P < .001) (Table 2). Short-acting reversible contraception users in the randomized group had a higher incidence of unintended pregnancy compared with the long-acting reversible contraception cohort (P = .01).

TABLE 2.

Probability of contraceptive method continuation and unintended pregnancy within 12 monthsa

| Variable | Preference SARC (n = 512) | Randomized SARC (n = 195) | Randomized LARC (n = 176) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number discontinuing original method | 188 | 90 | 39 |

| Person-years | 408.7 | 154.2 | 152.0 |

| Probability of method continuation (95% confidence interval)b | 63.3 (58.9–67.3) OC: 68.9 (64.2–73.2) DMPA: 36.7 (27.1–46.3) |

53.0 (45.7–59.8) OC: 58.1 (49.6–65.6) DMPA: 37.5 (23.7–51.3) |

77.8 (70.9–83.2) Implant: 77.5 (70.2–84.8) IUD: 78.4 (67.1–89.7) |

| Combining SARC preference and randomized cohorts | OC: 66.5 (62.3–70.3) DMPA: 37.0 (29.1–45.0) |

||

| Reason for method discontinuation, n, % | |||

| Wanted to get pregnant | 11 (5.9) | 2 (2.2) | 0 (0.0) |

| Not having sex | 26 (13.8) | 7 (7.8) | 0 (0.0) |

| Side effects | 53 (28.2) | 19 (21.1) | 30 (76.9) |

| Inconvenience of getting more | 20 (10.6) | 12 (13.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| Cost | 20 (10.6) | 2 (2.2) | 0 (0.0) |

| Got pregnant accidentally | 16 (8.5) | 6 (6.7) | 0 (0.0) |

| Forgot to take them or misplace them | 10 (5.3) | 6 (6.7) | 0 (0.0) |

| Other | 2 (1.1) | 2 (2.2) | 3 (7.7) |

| Forgot to get new packs | 2 (1.1) | 5 (5.6) | 0 (0.0) |

| IUD expulsion | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (15.4) |

| No reasons given | 28 (14.9) | 28 (31.1) | 0 (0.0) |

| Missing | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) |

| Number of unintended pregnancies | 24 | 10 | 1 |

| Person-years | 419.1 | 156.6 | 153.9 |

| Probability of unintended pregnancy (95% confidence interval)c | 5.5 (3.7–8.1) | 6.7 (3.6–12.1) | 0.7 (0.0–4.7) |

| Combining SARC preference and randomized cohorts | OC: 6.1 (4.3–8.6) DMPA: 4.6 (0.2–12.2) |

||

DMPA, depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (3 month injectable); IUD, intrauterine device; LARC, long-acting reversible contraception; OC, oral contraceptives; SARC, short-acting reversible contraception.

Eleven participants were lost to follow-up and are not included

Primary comparison between randomized groups: P < .001; secondary comparison between SARC groups: P = .04

Primary comparison between randomized groups: P = .01; secondary comparison between SARC groups: P = .77.

In the secondary comparisons involving only short-acting reversible contraception users, the continuation probability was higher in the preference group (63.3% [95% confidence interval, 58.9–67.3]) compared with the randomized group (53.0% [95% confidence interval, 45.7–59.8)] P = .04). However, the short-acting reversible contraception randomized group and short-acting reversible contraception preference group had statistically equivalent rates of unintended pregnancy (P = .77).

For specific products, depot medroxyprogesterone acetate users had the lowest continuation probabilities; the subdermal implant and the intrauterine device (combining the 2 types of intrauterine products) had the highest. Graphically, the pattern of unintended pregnancy for preference and randomized short-acting reversible contraception users was similar and on a far different path compared with long-acting reversible contraception users (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Cumulative probabilities of unintended pregnancy by study cohort

In the supporting analysis using proportional hazards modeling in the randomized cohort, we controlled for age, Hispanic ethnicity, education, motivation to opt for randomization, and desire for more children. Compared with long-acting reversible contraception users, short-acting reversible contraception users were more likely to discontinue from the assigned contraception with an adjusted hazard ratio of 2.3 (95% confidence interval, 1.6–3.5) and also more likely to experience unintended pregnancy (adjusted hazard ratio, 11.6 [95% confidence interval, 1.4–97.0]) (data not shown).

In comparing the experiences of the preference short-acting reversible contraception cohort with the randomized short-acting reversible contraception cohort, we controlled for Hispanic ethnicity, education, months with current partner, health insurance, and employment status: the risks of discontinuation between these 2 cohorts were statistically similar (adjusted hazard ratio, 0.8 [95% confidence interval, 0.6–1.0]), and the risks of unintended pregnancy were also statistically similar (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.0 [95% confidence interval, 0.5–2.1]) (data not shown).

About 78% of participants randomized to long-acting reversible contraception were happy/neutral with their initial method; however, this level was significantly lower than short-acting reversible contraception users (Table 3). Yet among the subset of participants still using the original method at 12 months, happiness rates (88–92%) were similar across the cohorts. Long-acting reversible contraception users who had the product removed were disproportionately unhappy compared with other discontinuers. When participants were asked about using the product in the future and whether they would recommend the product to friends, similar patterns to happiness emerged in examining continuers and discontinuers.

TABLE 3.

Measures of satisfaction with initial method as assessed at 12 months, by cohort and method discontinuation status

| Totala |

Continuing users |

Discontinuers |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measure | Pref SARC (n = 489) | Rand SARC (n = 188) | Rand LARC (n = 172) | Pref SARC (n = 308) | Rand SARC (n = 98) | Rand LARC (n = 135) | Pref SARC (n = 181) | Rand SARC (n = 90) | Rand LARC (n = 37) |

| Level of happiness with method, % distributionb,c | |||||||||

| Happy | 79.6 | 75.5 | 71.5 | 89.6 | 91.8 | 88.1 | 62.4 | 57.8 | 10.8 |

| Neutral | 11.0 | 13.8 | 7.0 | 3.9 | 5.1 | 5.2 | 23.2 | 23.3 | 13.5 |

| Unhappy | 9.4 | 10.6 | 21.5 | 6.5 | 3.1 | 6.7 | 14.4 | 18.9 | 75.7 |

| Would use method again in future, %b,c,d | 87.9 | 80.8 | 75.6 | 96.1 | 93.49 | 89.6 | 74.0 | 66.7 | 24.3 |

| Recommended that a friend/relative try the method, %b,c,d,e | 81.1 | 68.9 | 79.3 | 88.7 | 75.0 | 89.4 | 68.2 | 62.0 | 43.2 |

LARC, long-acting reversible contraception; Pref, preferred; Rand, randomized; SARC, short-acting reversible contraception.

Missing data on satisfaction variables: pref SARC (n = 23), rand SARC (n = 7), and rand LARC (n = 4)

P < .05 for total column comparisons

P < .05 for discontinuing user column comparisons

P < .05 for continuing user column comparisons

Among those who discussed the topic with a friend or relative.

Comment

Our research found scientific evidence that typical users of short-acting reversible contraception can find long-acting reversible contraception highly acceptable. The forces and factors that lead many typical short-acting reversible contraception users to eventually experience unintended pregnancy were demonstrably suppressed and overcome by random assignment and the decision to try long-acting reversible contraception.

From a population and cohort perspective, the initial decisions to try long-acting reversible contraception, regardless of any subsequent decisions to stop using it, provided substantially higher protection from unintended pregnancy than short-acting alternatives. The random assignment and intention-to-treat analysis confirmed commonly accepted benefits attributed to long-acting reversible contraception that have been based on observational studies. Moreover, the experiences of the 2 short-acting reversible contraception cohorts were similar; this builds a bridge of generalizability between a randomized population and typical short-acting reversible contraception users who have clear preferences and receive contraceptives in the usual way.

Our estimates of probabilities of unintended pregnancy should not replace standard measures of contraceptive effectiveness. Classic approaches for estimating typical contraceptive effectiveness do not count pregnancies after self-reported method discontinuation; only pregnancies that occur during self-reported product use are attributed to the product (failure). This strategy allows users to attribute failure to a product, regardless of whether it was used correctly.

In contrast, our intent-to-treat approach obviates the need to consider any reports of method discontinuation; as such, we would tend to overestimate failure rates. Despite these differences in approaches, we found our 12 month failure confidence intervals of 4–12% for short-acting reversible contraception and 0–5% for long-acting reversible contraception were similar to previously published contraceptive effectiveness rates. For example, the most widely cited typical use 12 month failure rates are estimated at 9% for pills, 6% for injectable hormonal contraception, and <1% for intrauterine devices.4 Also, the largest contemporary contraceptive cohort study in the United States reported 12 month failure rates of 5% for pills and 0.3% for long-acting reversible contraception.3

Level of happiness with long-acting reversible contraception was high in our population who was initially seeking short-acting reversible contraception. Our overall estimate of happy (71%), combined with neutral feelings (7%), is somewhat consistent with levels of satisfaction with long-acting reversible contraception (79–86%) from observational studies of women seeking long-acting reversible contraception.2 Because even the randomized population was initially seeking short-acting reversible contraception, the half who started out on long-acting reversible contraception perhaps began their experience on a lower trajectory of satisfaction, compared with the half who started their preferred method. Despite these findings, it certainly bears acknowledging that not all women want long-acting reversible contraception, and it is clear that not all women will be satisfied with long-acting reversible contraception.

Our results provide additional evidence for policy recommendations calling for wider access to long-acting reversible contraception to improve reproductive health in the United States For example, the American Academy of Pediatrics now recommends long-acting reversible contraception as a first-line option for adolescents who choose not to be abstinent.12 The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists has issued similar recommendations.13,14

For decades, long-acting reversible contraception has been identified as the most cost-effective form of reversible contraception.5,15,16 The high expectations for long-acting reversible contraception, based on observational research, largely assume that patterns of long-acting reversible contraception use and resulting benefits can be expected in other populations; our study validates many of those assumptions.

Access to long-acting reversible contraception is still lacking in the United States; product availability ranges from 32% to 56% in office-based facilities and 36% to 60% in Title X clinics.17 Providers cite lack of training, inadequate reimbursement, and stocking problems (high upfront costs of long-acting reversible contraception discourage providers from keeping adequate supplies).18

In a nationwide survey of family physicians, less than half offered intrauterine device counseling or services, yet 95% of those interviewed believed that their patient population would be receptive to learning about the intrauterine device.19 Patient cost barriers, however, are fading with Medicaid expansion and with passage and more complete implementation of the Affordable Care Act.20-22 However, many states are still underperforming in terms of removing the cost barriers.

The main weakness of our study is that complete interchangeability of contraceptive regimens at a family-planning consultation is not a practical concept. Clients should always make final decisions about what product to use, and for many, long-acting reversible contraception and short-acting reversible contraception are not substitutable. For long-acting reversible contraception, fear of pain/injury from insertion or continued use is an obstacle to uptake; aversion to implanted devices also deters use.8 A 2012 internet survey of 382 US women aged 18–29 years found varied interest in trying an intrauterine device: 48% were unsure, 20% were interested, and 32% were not interested.23

External validity of our findings are limited by a willingness to be randomized to a therapy and the fact that we recruited only women with good follow-up potential. Our results, however, provide many short-acting reversible contraception users with new evidence and encouragement to consider trying long-acting reversible contraception, given the high acceptability and proven higher protections from unintended pregnancy. In no way should our results be used to limit contraceptive choices.24,25

The previously cited limitation also ties in with our decision not to apply strict intent-to-treat data analysis principles: only women who started the randomized assignment were followed up and included in our analysis (see Materials and Methods section). Instead of using randomization to evaluate an intervention, we used randomization to reduce selection bias and give participants an opportunity to try a product without financial risk. Nevertheless, to address concerns that we did not follow strict intent-to-treat principles after randomization (16 of 194 women refused the random assignment to long-acting reversible contraception), we modeled what would have occurred if those 16 long-acting reversible contraception participants experienced unintended pregnancy at rates similar to the short-acting reversible contraception users.

After 3000 bootstrapping samplings, we estimated an unintended pregnancy probability of 1.2% (95% confidence interval, 0.6–1.9), which is still statistically lower than 6.7% (95% confidence interval, 3.6–12.1), which was the rate among short-acting reversible contraception users.

Unintended pregnancy and abortion are stubborn problems in the United States. In the most recent data from 2011, 2.8 million unintended pregnancies occurred; this represented 45% of the total number of pregnancies in that year.26 Moreover, 42% of the unintended pregnancies ended in abortion (totaling more than 1 million procedures). These unacceptable levels have not changed much since the mid-1990s. More voluntary uptake of long-acting reversible contraception will help avert many unintended pregnancies and the negative consequences. Long-acting reversible contraception appears highly acceptable and beneficial, even for women who are not initially interested in trying it.

FURTHER POINTS.

Any (grey) halftones (photographs, micrographs, etc.) are best viewed on screen, for which they are optimized, and your local printer may not be able to output the greys correctly.

If the PDF files contain colour images, and if you do have a local colour printer available, then it will be likely that you will not be able to correctly reproduce the colours on it, as local variations can occur.

If you print the PDF file attached, and notice some ‘non-standard’ output, please check if the problem is also present on screen. If the correct printer driver for your printer is not installed on your PC, the printed output will be distorted.

Acknowledgments

This study is registered on ClinicalTrials.gov (number NCT01299116).

This study was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development of the National Institutes of Health under award R01HD067751. In addition, this grant received product donations from Teva Pharmaceuticals, Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals, Inc, and Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp. Finally, an anonymous donor provided additional funding.

Dr Hubacher has served on scientific advisory boards for Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals and Teva Pharmaceuticals. As principal investigator for this research, he received product donations from Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals, Teva Pharmaceuticals, and Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp.

Footnotes

The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the funders, FHI360, Planned Parenthood Federation of America, Inc, or Planned Parenthood South Atlantic.

The other authors report no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Finer LB, Henshaw SK. Disparities in rates of unintended pregnancy in the United States, 1994 and 2001. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2006;38:90–6. doi: 10.1363/psrh.38.090.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peipert JF, Zhao Q, Allsworth JE, et al. Continuation and satisfaction of reversible contraception. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117:1105–13. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31821188ad. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Winner B, Peipert JF, Zhao Q, et al. Effectiveness of long-acting reversible contraception. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1998–2007. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1110855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Trussell J. Contraceptive efficacy. In: Hatcher R, Trussell J, Nelson A, Cates W, Kowal D, Policar M, editors. Contraceptive technology. 20th revised ed. Ardent Media, Inc; Atlanta (GA): 2011. pp. 779–863. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Trussell J, Leveque JA, Koenig JD, et al. The economic value of contraception: a comparison of 15 methods. Am J Public Health. 1995;85:494–503. doi: 10.2105/ajph.85.4.494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Trussell J, Hassan F, Lowin J, Law A, Filonenko A. Achieving cost-neutrality with long-acting reversible contraceptive methods. Contraception. 2015;91:49–56. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2014.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Daniels K, Daugherty J, Jones J. NCHS data brief, no 173. National Center for Health Statistics; Hyattsville (MD): 2014. Current contraceptive status among women aged 15–44: United States, 2011–2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hubacher D, Spector H, Monteith C, Chen PL, Hart C. Rationale and enrollment results for a partially randomized patient preference trial to compare continuation rates of short-acting and long-acting reversible contraception. Contraception. 2015;91:185–92. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2014.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kaplan EL, Meier P. Nonparametrics estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Stat Assoc. 1958;53:457–81. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cox DR. Regression models and life tables. J R Stat Soc Series B. 1972;34:187–220. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hollis S, Campbell F. What is meant by intention to treat analysis? Survey of published randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 1999;319:670–4. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7211.670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ott MA, Sucato GS. Contraception for adolescents. Pediatrics. 2014;134:e1257–81. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-2300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Committee on Adolescent Health Care Long-Acting Reversible Contraception Working Group Adolescents and long-acting reversible contraception: implants and intrauterine devices. American College of Obstetricians Gynecologists Committee opinion no. 539. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120:983–8. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182723b7d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Long-acting reversible contraception: implants and intrauterine devices. ACOG Practice bulletin no. 121. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118:184–96. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318227f05e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Trussell J. Update on the cost-effectiveness of contraceptives in the United States. Contraception. 2010;82:391. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2010.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mavranezouli I. The cost-effectiveness of long-acting reversible contraceptive methods in the UK: analysis based on a decision-analytic model developed for a National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) clinical practice guideline. Hum Reprod. 2008;23:1338–45. doi: 10.1093/humrep/den091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Contraceptive methods available to patients of office-based physicians and title X clinics—United States, 2009–2010. MMWR Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60:1–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kavanaugh ML, Jerman J, Ethier K, Moskosky S. Meeting the contraceptive needs of teens and young adults: youth-friendly and long-acting reversible contraceptive services in US family planning facilities. J Adolesc Health. 2013;52:284–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.10.276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harper CC, Henderson JT, Raine TR, et al. Evidence-based IUD practice: family physicians and obstetrician-gynecologists. Fam Med. 2012;44:637–45. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Internal Revenue Service, Department of the Treasury, Employee Benefits Security Administration, Department of Labor, Centers for Medicare Medicaid Services, Department of Health Human Services Coverage of certain preventive services under the Affordable Care Act. Final rules. Fed Regist. 2013;8:39869–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Finer LB, Sonfield A, Jones RK. Changes in out-of-pocket payments for contraception by privately insured women during implementation of the federal contraceptive coverage requirement. Contraception. 2014;89:97–102. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2013.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bearak JM, Finer LB, Jerman J, Kavanaugh ML. Changes in out-of-pocket costs for hormonal IUDs after implementation of the Affordable Care Act: an analysis of insurance benefit inquiries. Contraception. 2016;93:139–44. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2015.08.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gomez AM, Clark JB. The relationship between contraceptive features preferred by young women and interest in IUDs: an exploratory analysis. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2014;46:157–63. doi: 10.1363/46e2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Higgins JA. Celebration meets caution: LARC's boons, potential busts, and the benefits of a reproductive justice approach. Contraception. 2014;89:237–41. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2014.01.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gubrium AC, Mann ES, Borrero S, et al. Realizing reproductive health equity needs more than long-acting reversible contraception (LARC). Am J Public Health. 2016;106:18–9. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Finer LB, Zolna MR. Declines in unintended pregnancy in the United States, 2008–2011. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:843–52. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1506575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]