Abstract

Despite its former reputation as being immunosuppressive, it has become evident that radiation therapy can enhance antitumor immune responses. This quality can be harnessed by utilizing radiation as an adjuvant to cancer immunotherapies. Most studies combine the standard radiation dose and regimens indicated for the given disease state, with novel cancer immunotherapies. It has become apparent that low-dose radiation, as well as doses within the hypofractionated range, can modulate tumor cells making them better targets for immune cell reactivity. Herein, we describe the range of phenotypic changes induced in tumor cells by radiation, and explore the diverse mechanisms of immunogenic modulation reported at these doses. We also review the impact of these doses on the immune cell function of cytotoxic cells in vivo and in vitro.

KEYWORDS : cancer, cytotoxic cells, immunogenic modulation, immunotherapy, low-dose radiotherapy, radiation, single-dose radiotherapy, T cells

The ability of ionizing radiation (IR) to influence the immune response against tumors has become more and more attractive as the development of novel cancer immunotherapies (CIT) has rapidly expanded and these agents have come into wider clinical use. Beginning in 2010, Provenge (Sipuleucel-T), Yervoy (ipilimumab), Keytruda (pembrolizumab) and Opdivo (nivolumab) have all received US FDA approval for the treatment of cancer. While only four CITs have received FDA approval at this time, there are numerous others under preclinical study and in clinical development. As a result, the immune enhancing powers of radiation are becoming a valued aspect and important use of radiotherapy (RT) [1].

Radiation can be used as an adjuvant to immunotherapies in several ways. First, it can induce a type of cell death in a subset of susceptible tumor cells, which can then activate antigen uptake, cell maturation and presentation by antigen-presenting cells (APCs). This immunogenic cell death (ICD) is identified by three main hallmarks on tumor cells; calreticulin exposure, ATP release and HMGB1 release [2]. APCs responding to ICD can subsequently induce other immune cells that are capable of attacking the surviving tumor cells. This body of work has been highlighted in a number of excellent reviews [3–7]. Second, radiation can cause molecular alterations in tumor cells in a manner that directly sensitizes tumor cells to immune cell-mediated killing. This property of radiation is referred to as immunogenic modulation (IM) of tumor cells [8,9]. Pre-existing (endogenous) immune cells, or those induced or activated by vaccine, may not be able to act once they reach tumors if the tumor microenvironment (TME) is immunosuppressive or the tumor cells themselves are suppressive or suboptimal targets. Modulated tumor cells surviving exposure to radiation, either because they are radio-resistant or because they receive sublethal doses, can become better targets for antitumor immune cells. Third, radiation can alter the activity and function of immune cells directly. Which of these three situations occurs is likely influenced by the dose and delivery scheme used (single dose vs separated into smaller fractions), though they are likely not mutually exclusive.

The immune enhancing effects of RT, and the different ways that RT has been combined with CITs clinically and preclinically, have been recently reviewed elsewhere [10,11]. Exciting outcomes have been observed in patients receiving RT for palliation with no intent to cure [12,13]. Similar success has been reported when higher doses of RT were used [14–16]. These clinical outcomes are even more exciting because they report immune mediated regression of not only the irradiated tumor, but also of distant tumors outside of the radiation field (i.e., abscopal response). Though these abscopal responses and clinical outcomes are thrilling, there remains significant room for improvement [10]. It is not fully understood what induces such responses on the cellular and molecular level, and it is not yet possible to routinely recapitulate these outcomes.

The focus of this review is on IM of tumor cells and the influence of radiation dose on the phenotype of tumor cells. The use of radiation for IM would not rely on RT to induce a de novo immune response, but would instead be used to specifically complement the elaborate CITs already in development [17,18]. At this time, RT is not routinely incorporated into most CIT approaches specifically for its IM properties. Our review will consider the effect of both low doses of radiation (≤2 Gy; see the 'Immunomodulation by low-dose radiotherapy' section), and hypofractionated doses (2–25 Gy; see the 'Immunomodulation by hypofractionated doses of radiation' section), on gene expression in cells surviving radiation, focusing on changes that can directly enhance cellular attack of tumor cells. We also consider the impact of these radiation doses directly on immune cells themselves both phenotypically (see the 'Immunomodulation by low-dose radiotherapy' and 'Immunomodulation by hypofractionated doses of radiation' sections) and functionally (see the 'Immunomodulation at work' section). Studies comparing responses to single dose (SD) versus multifraction (MF) delivery have been recently reviewed by others [19,20]. Here we leave our review to observations made in tumor cells surviving SD radiation, or systems where radiation alone has no observable tumor control.

• Immunomodulation by low-dose radiotherapy – ≤2 Gy

IM of tumor cells following low-dose radiotherapy doses

There are many reports on the ability of IR to modulate the expression of genes that are important for immune attack of tumor cells. However, much of the information available is from cells receiving high doses of radiation intended to kill tumor cells, and much less information is available from tumors treated with low or sublethal doses of radiation; yet, changes in several important immune genes have been reported in tumor cells treated with low-dose radiotherapy (LD-RT). MHC-I is responsible for presentation of endogenous antigens to cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs). Reits et al. exposed a human melanoma cell line (MelJuSo) to radiation and quantified cell surface MHC-I complexes 18 h later. Radiation induced a dose-dependent increase in MHC-I expression in vitro and increases in MHC-I were observed beginning at 1 Gy. Furthermore, they observed more polyubiquitinated proteins available for proteasomal degradation after radiation doses as low as 1 Gy. This and other studies revealed that radiation can lead to more peptide diversity for MHC-I antigen presentation, in addition to enhanced MHC-I expression [21–23]. The stress ligands MICA/B can bind to cognate receptors (NKG2D) on cytokine-inducible lymphocytes, NK cells and T cells causing activation of these cells [24]. Liu et al. irradiated human myeloma cells (KAS-6/1) at various doses and analyzed the cells for expression of MICA/B 24 h postirradiation [25]. A dose-dependent increase in both MICA/B expression at doses as low as 2 Gy was observed. After appropriate activation, CTLs and NK cells can kill tumor targets expressing death receptors such as Fas (CD95) on their surface, and there is some evidence of increased Fas expression following treatment of tumors with LD-RT. In one study, Sheard et al. treated human colorectal (HCT116) and human breast cancer (MCF7) cells with 2 Gy IR and observed moderate upregulation of Fas [26]. The ligand for Fas, FasL, sends apoptotic signals into Fas expressing cells. Abdulkarim et al. irradiated a human nasopharyngeal cancer (C15) cell line at various doses and measured FasL induction [27]. Fas is constitutively expressed in this NPC cell line prior to irradiation, but following 2 Gy IR there was an increase in FasL on these cells. FasL expressing cells could possibly kill themselves and/or nearby Fas-expressing cells, including infiltrating T cells. This is a rare example of LD-RT upregulating expression of a gene that could negatively impact T cells.

Mechanism of IM in tumor cells following LD-RT

Radiation has been paradoxically reported to be both proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory. As the key transcription factor for numerous immune factors, NF-κB has been investigated for its involvement in gene expression following LD-RT. The use of LD-RT to treat benign inflammatory or hypoproliferative conditions is well known [28,29], and inhibition of NF-κB is thought to be responsible for these anti-inflammatory activities. In this regard, Lodermann et al. observed a decrease in p38 (an upstream molecule of NF-κB) and AKT (a downstream molecule of NF-κB) following 0.5 Gy and 0.7 Gy of IR. Pajonk and colleagues reported that the 26S proteasome was a direct target of IR, and hypothesized that radiation-induced inhibition of the proteasome was a mechanism of NF-κB inhibition. This type of inhibition could modulate expression of numerous proinflammatory molecules, such as TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6, at the transcriptional level. Indeed, bladder cancer cells (ECV304) treated with 0.17–2 Gy induced a rapid, dose-dependent decrease in 26S proteasome activity. In turn, this inhibition prevented the phosphorylation, ubiquitination and subsequent degradation of the IκB regulatory complex leading to reduced translocation of NF-κB complex to the nucleus. While altered proteasome function induced by LD-RT is an attractive explanation for many of the observed transcriptionally regulated effects, via inhibition of NF-κB, more investigation is needed in this area as chronic low dose exposure has resulted in both stimulation and inhibition of NF-κB regulated genes [30]. Further, most studies have utilized doses higher than 2 Gy to investigate radiation-induced changes in gene expression in tumor cells and NF-κB activation is observed at higher doses. Thus IR appears to be able to both activate and inhibit NF-κB and the outcome may be dependent on dose, and perhaps tissue, under study.

Modulation of immune cells following LD-RT

The efficacy of RT is known to be influenced by the TME, including local expression of agents such as HIF-1 and VEGF [31]. However, the reciprocal is also true and LD-RT can directly modulate the efficacy of immune cells including macrophages, DCs, NK and lymphocytic cells. LD-RT in vitro (0.075 Gy) increases NK cell secretion of IFN-γ and TNF-α [32]. Nontumor bearing mice treated with 0.2 Gy × 4 total body irradiation (total 0.8 Gy) had an increase in NK and NK T cell numbers at 21 days post IR [33]. Increased amounts of IFN-γ, IL-12 and TNF-α from macrophages were detected 10 days post IR in these animals. Klug et al. observed that 2 Gy irradiation induced iNOS expression (and reduced HIF-1, Ym-1, Fizz-1 and arginase expression) indicating an induction of the M1 (proinflammatory) macrophage phenotype [34]. They further showed that iNOS inhibition blocked VCAM-1 expression on CD31+ endothelial cells, indicating endothelial cell activation, and that the capacity to support leukocyte transmigration was enhanced post IR via iNOS. Lodermann et al. observed a decrease in IL-1β secretion from LD-RT-induced macrophages, and found that this downregulation was correlated with reduced nuclear translocation of the p65 (RelA) subunit of the NF-κB complex [35]. In another study, direct treatment of macrophages with IR decreased IL-1β (0.5–2 Gy) and increased TGF-β (0.1–0.5 Gy) expression with a decreased in nuclear localization of NF-κB also observed [36]. This demonstrates that LD-RT can change macrophage phenotype. Moreover, Liu et al. observed increased expression of CD80 and CD86 on macrophages following LD-RT suggesting an increased capacity for costimulation of T cells [37]. LD-RT can also impact other APCs such as DCs. Shigematsu et al. treated murine DCs with various doses of IR (0.02, 0.05, 0.1, 0.5, 1 Gy) and observed increased secretion of IL-12 and increased expression of IL-2 and IFN-γ mRNA at doses as low as 0.05 Gy from DCs [38]. They further observed that LD-RT had no effect on proliferation or maturation of the DCs. Whole body irradiation of nontumor bearing mice with 0.075 Gy caused an increase in CD28 expression concomitant with a reduction in CTLA-4 expression on splenic lymphocytes [37]. Conversely, treatment with 2 Gy produced reciprocal changes in these same cells. Treatment of TREGS from rats with 0.15 Gy of radiation in vitro reduced the expression of CTLA-4 [39], which is associated with the suppressive function of these cells. These findings demonstrate that LD-RT can directly alter the state of some immune cells with important roles in antitumor immunity.

The ability of lower dose ionizing radiation (<0.2 Gy) to activate immune cells has been recently reviewed by Farooque et al. [40], and we now present a table summarizing important immune relevant changes in both tumor cells and immune cells following low to intermediate doses of IR in Table 1.

Table 1. . Low-dose radiotherapy range (≤2 Gy).

| IM gene | Tissue (up/down) | Dose (Gy) | mRNA or protein | Role | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Tumor cells | |||||

| MHC-I |

Melanoma (Hu); Up |

1 |

Protein |

Antigen presentation |

[21] |

| FAS |

CRC, BrCa (Hu); Up |

2 |

Protein |

Transmits apoptotic signals into cells |

[26] |

| FasL |

NPC (Hu); Up |

2 |

Protein |

Inducer of apoptosis |

[27] |

| NKG2DL (MICA/B) |

Myeloma (Hu); Up |

2 |

mRNA/protein |

Increased recruitment and function of NK cells |

[25] |

|

Immune cells | |||||

| IFN-γ | NK cells; Up | 0.75 | Protein | Activation of CD8 T cells; Th1 promoting | [32] |

| Macrophages; Up | 0.8 | mRNA | [33] | ||

| |

DCs; Up |

0.05 |

mRNA |

|

[38] |

| TNF-α | NK; Up | 0.75 | Protein | Inducer of tumor apoptosis | [32] |

| |

Macrophages; Up |

0.8 |

mRNA |

|

[33] |

| IL-12 | Macrophage; Up | 0.8–0.075 | mRNA/protein | Th1 promoting cytokine | [33,37] |

| |

DCs; Up |

0.05 |

mRNA/protein |

|

[38] |

| IL-10 |

Macrophages; Down |

0.075 |

Protein |

Immunosuppressive cytokine |

[37] |

| IL-1β | Macrophages; Down | 0.5–0.7 | Protein | Proinflammatory action | [35,36] |

| |

|

0.5–2 |

Protein |

|

|

| TGF-β |

Macrophages; Up |

0.1–0.5 |

Protein |

Inhibits CTL function |

[36] |

| iNOS |

Macrophage; Up |

2 |

Protein |

M1 associated, inducer of cytotoxic mediator NO |

[34] |

| Arginase |

Macrophages; Down |

2 |

Protein |

M2 associated enzyme |

[34] |

| HIF1 |

Macrophages; Down |

2 |

Protein |

Proangiogenic; tumor promoting |

[34] |

| CD80/86 |

Macrophages; Up |

0.075–2 |

Protein |

Increased T-cell costimulation |

[37] |

|

IL-2 |

DCs; Up |

0.05 |

mRNA |

T-cell proliferation cytokine |

[38] |

| CD28 | Lymphocytes; Up | 0.075 | Protein | Transmits positive signal into T cells | [37] |

| |

Lymphcytes; Down |

2 |

Protein |

|

|

| CTLA-4 | Lymphocytes; Down | 0.075 | Protein | Inhibitory signal for cytotoxic cells | [37] |

| Lymphocytes; Up | 2 | Protein | |||

| TREGS; Down | 0.15 Gy | Protein | [39] | ||

BrCa: Breast carcinoma; CRC: Colorectal carcinoma; CTL: Cytotoxic T lymphocyte; DC: Dendritic cell; Hu: Human; Ms: Mouse; NPC: Nasopharyngeal carcinoma.

• Immunomodulation by hypofractionated doses of radiation

IM of tumor cells within the hypofractionated dose range

Doses between 2 and 25 Gy have been evaluated extensively for enhancement of antitumor immune attack. In the context of radiation biology, a radiation dose of 5 Gy is in the moderate hypo-fractionated range, and 10 Gy dose is considered in the extreme hypo-fractionated range [41]. Stereotactic body radiation therapy has been administered in fractions up to 15 Gy [42]. As a result, the majority of IM studies have been conducted within these dose ranges, and there is much information available about the diverse immune relevant genes that are changed post IR (Table 2). Though typically delivered in multiple fractions over time to reach a higher cumulative delivery dose to patients, here we review the impact of mostly single dose (SD) exposure on the modulation of surviving cells.

Table 2. . Hypofractionated dose range (>2 to <25 Gy).

| IM gene | Tissue (up/down) | Dose (Gy) | mRNA or protein | Role | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Signal 1 | |||||

| MHC I | Mel (Hu, Ms); Up | 1–25 | Protein | Antigen presentation | [21] |

| Mel (Ms); Up | 15 | Protein | [43] | ||

| CRC, Lu, PCa (Hu); Up | 10–20 | Protein | [44] | ||

| Glioma (Ms); Up | 4 | Protein | [45] | ||

| |

PCa (Hu); Up |

25 |

Protein |

|

[46] |

| TAA peptides |

(Hu, Ms); Up |

10–25 |

Peptide saturation |

T-cell target |

[21] |

| TAA |

Tumor lines (Hu); Up |

10–20 |

Protein |

|

[44,46–47] |

|

Effector signals | |||||

| OX40L, 4-1 BBL | CRC lines (Hu); Up | 10 | mRNA/protein | Positive co-stimulation | [48] |

| |

PCa Lines (Hu); Up |

5–15 |

Protein |

|

[49] |

| CD70, ICOSL |

PCa lines (Hu); Up |

5–15 |

Protein |

Positive co-stimulation |

[49] |

| PD-L1 | PCa; Down | 5–15 | Protein | Inhibition of T cells | [49] |

| BrCa tumor (Ms-TUBO); Up | 12 | Protein | [50] | ||

| |

PCa tumor; Up/down |

10 |

mRNA |

|

[51] |

| CTLA-4 |

PCa tumor (Hu); Down |

5–15 |

Protein |

Inhibition of T cells |

[49] |

| ICAM-1 | CRC, Lu, PCa, HN (Hu); Up | 10–20 | mRNA protein | Mediates leukocyte adhesion to tumor cells | [44,52] |

| BrCa (Ms); Up | 2 × 12 Gy | Protein | [53] | ||

| BrCa (Hu); Up | 10 | Protein | [47] | ||

| |

Tumor lines (Hu); Up |

10–20 |

mRNA/protein |

|

[54] |

| MICB, ULBP1/2 | Tumor lines (Hu); Up | 20 | RNA | NKG2DLs, trigger cytotoxic cells | [55] |

| |

|

|

Protein |

|

|

| RAE-1 |

BrCa tumor (Ms); Up |

2 × 12 Gy |

Protein |

NKG2DL, trigger cytotoxic cells |

[53] |

|

Death receptors | |||||

| FAS | Tumor lines (Hu); Up | 10–20 | Protein | Transmits death signal into cells | [44] |

| Tumor line (Ms); Up | 8–10 | Protein | [56] | ||

| BrCa, CRC (Hu); Up | 10–16 | Protein | [26,57] | ||

| |

Esophageal lines; Up |

3–6 |

Protein |

|

[58] |

| DR4 | CRC (Hu); Up | 2.5–10 | Protein | [59] | |

| |

CRC, Lu (Hu); Up |

10 |

Protein |

|

[60] |

| DR5 |

CRC (Hu); Up |

2.5–10 |

Protein |

|

[59] |

|

Cytokines | |||||

| TGF-β1 |

PCa tumor (Ms); Up |

6–10 |

mRNA/protein |

Immunosuppressive |

[61] |

| GMC-SF, IL-6 | PCa tumor (Hu); Up | 10 | Protein | DC maturation | [51,62] |

| |

Lu (Hu); Up |

25 |

Protein |

|

|

| TNF-α |

Sarcoma (Hu); Up |

5 |

Protein |

Inducer of apoptosis |

[63] |

|

Chemokines | |||||

| CXCL16 |

BrCa (Ms); Up |

2 × 12 Gy |

Protein |

Recruits immune cells |

[64] |

|

CCR2, CCL2, CXCR6, CXCL16 |

HPV tumor; Up |

14 |

mRNA |

|

[65] |

|

Immune cells | |||||

| CD70 | DCs (Hu); Up | 10 | Protein | Costimulates T cells | [66] |

| |

DCs (Ms); Up |

10 |

Protein |

|

[67] |

| CD86 | DCs (Hu); No change | 10 | Protein | Costimulates T cells | [66] |

| DCs (Ms); Up | 10 | Protein | [67] | ||

| |

Macrophages (Hu); Up |

2–20 |

Protein |

|

[68] |

| CD40 |

Macrophages (Hu); Up |

2–20 |

Protein |

Costimulates T cells |

[68] |

| MHC-II |

Macrophages (Hu); Up |

2–20 |

Protein |

Antigen presentation |

[68] |

| IL-12 |

DCs (Hu); Up |

10 |

Protein |

Promotes Th1 responses |

[66] |

| IL-23 |

DCs (Hu); Up |

20 |

Protein |

Promotes Th1 responses |

[66] |

| FoxP3 |

TREGS (Hu); Down |

7.5–30 |

Protein |

TREG transcription factor |

[69] |

| CD45RO |

TREGS (Hu); Down |

7.5–30 |

Protein |

TREG activation marker |

[69] |

| CD62L |

TREGS (Hu); Down |

7.5–30 |

Protein |

Promotes trafficking to lymph nodes |

[69] |

| TGF-β1 |

TREGS (Hu); Down |

30† |

Protein |

Immunosuppressive |

[69] |

| PD-L1 |

DCs, macrophages; Up |

12 |

Protein |

Inhibitor of T cells |

[50] |

| Arginase and COX-2 |

Macrophages; Up |

25 |

RNA/protein |

M2 associated, cancer promoting |

[70] |

| iNOS | Macrophages; Up | 25 | RNA/protein | M1 associated, inducer of cytotoxic mediator NO | [70] |

†Dose outside the 2–25 dose range of the other studies.

BrCa: Breast carcinoma; CRC: Colorectal carcinoma; DC: Dendritic cell; HN: Head and neck; HPV: Human papilloma virus; Hu: Human; iNOS: Inducible NO synthase; Lu: Lung; Mel: Melanoma; Ms: Mouse; NO: Nitric oxide; PCa: Prostate cancer.

Signal 1

CTLs must see target tumor-associated antigens (TAA) displayed in MHC-I, and several studies have shown that IR can modulate this signal within tumor cells. Lugade et al. demonstrated that irradiated tumors (15 Gy) had an increased capacity for presenting antigen to specific T cells in an MHC-dependent manner [43]. RT upregulated MHC class I expression to high levels on glioma cells in mice [45]. Reits et al. observed a dose-dependent increase in MHC class I surface expression 18 h post IR in vitro in a human melanoma cell line (MelJuSo) at doses as high at 25 Gy [21]. Further, local irradiation (25 Gy) of mice in vivo resulted in similar increases in MHC within the irradiated tissue 24 h post IR. Additionally, cells exposed to 4 Gy IR exhibit increased TAP mobility when analyzed 1 h later and increased polyubiquitination following exposure to 10 Gy, indicating increased protein degradation. Further analysis revealed that prolonged peptide saturation levels are directly related to increased radiation dose [21]. In vitro, human colorectal, lung and prostate cancer cell lines showed increase expression of various surface molecules, including MHC-I [44], 72 h post irradiation (10 and 20 Gy). Eight of the 23 lines increased surface expression of MHC-I and 17 of 23 increased surface expression of one or more of the TAAs evaluated (CEA or MUC). Gameiro et al. examined radiation’s ability to induce IM of human breast cancer (MDA-231), non-small-cell lung cancer (H522) and prostate cancer cells (LNCaP) 72 h after 10 Gy IR. Radiation significantly induced the surface expression MHC class I and TAAs in these diverse cell lines [47].

Signal 2

Following recognition of antigen in MHC-I, naive T cells must also receive co-stimulatory signals for full activation and expansion. Once activated, the activity and function of effector T cells are also enhanced by signaling through co-stimulatory molecules such as CD27, ICOS, OX-40 and 4–1BB [71]. Conversely, the actions of effector T cells can be inhibited by co-inhibitory signals through CTLA-4 or PD-1. We have recently demonstrated that colorectal tumor cells surviving 10 Gy radiation have increased mRNA and surface protein expression of both OX-40L and 4–1BBL [48]. This observation was further extended to prostate cancer cells, and an increase in the surface expression of 4–1BBL, ICOS-L, OX-40L and CD70 was observed in three human prostate cancer cell lines post IR [49]. Changes in OX-40L and 4–1BBL were dose-dependent (5–15 Gy) and increased expression was observable even after exposure to 15 Gy. By contrast, a decrease in the expression of the inhibitory molecule PD-L1 after exposure to 10 Gy IR was observed in some of these same cells, again in a dose dependent manner. Interestingly, reduced expression of PD-L1 remained stable even when evaluated 6 days post irradiation. Variable modulation of CTLA-4 expression in tumor cells (normally expressed on T cells themselves) was reported. One of the tumor cell lines decreased CTLA-4 expression (DU145), while the other cell lines increased expression (PC3 and LNCaP). In contrast to tumor cells, normal prostate cells (PrEC) exhibited much less modulation of the genes evaluated. Aryankalayil et al., assessed the immunomodulatory changes in three human prostate cancer cell lines following exposure to 10 Gy fractionated (1 Gy × 10) or single dose (10 Gy × 1) radiation [19]. They found the mRNA for a variety of immune-related genes to be modulated 24h post IR. Among the modulated genes only PD-L1 had an obvious and direct link to cell-mediated attack against tumor cells. Exposure to 10Gy SD radiation induced the downregulation of PD-L1 gene expression in PC3 cells. It is important to note that multifraction (MF) delivery (1 Gy × 10) had the opposite effect in DU145 and caused upregulation of PD-L1 mRNA. No change in expression of this gene was reported in LNCaP. These data are in contrast to Bernstein et al., using SD, showing down-modulation of the protein from the cell surface at a later time post IR. Collectively, these studies could be highlighting major differences in IM response between SD and MF delivery. In the clinic, radiation is delivered in multiple smaller fractions to spare normal tissue, and the range of IM likely depends on fractions and fraction doses given [51]. In vivo, mice bearing breast cancer tumors (TUBO) were locally irradiated with 12 Gy of RT and PD-L1 expression was increased in tumor cells [50]. Overall, expression of these co-stimulatory and co-inhibitory molecules is particularly interesting because it suggests that modulated tumors are not simply rendered more sensitive to attack by T cells but may be signaling back into responding immune cells and modifying their biological response.

Cell adhesion molecules such as ICAM-1 can enhance CTL and NK cell interaction with target cells, and also appear to deliver co-stimulatory signals into the responding cells. More than half of 23 diverse human tumor cell lines evaluated (colorectal, lung, and prostate) increased expression of ICAM-1 following 10–20 Gy of external beam radiation (EBRT) [44]. Similar observations have been seen in other cancer cell types including breast [47], head and neck [52], and skin [54]. Apart from EBRT, Chakraborty et al. have reported that exposure to a radionucleotide can also alter the phenotype of tumor cells. Samarium-153-EDTMP, a bone-seeking radio nucleotide, is used in palliation of bone metastasis. This study demonstrated that exposure to 153Sm-EDTMP induced several immunostimulatory molecules, including ICAM-1, on prostate and lung cancer cells. Importantly, IM of ICAM-1 has also been reported 48 h after in vivo local RT (12 Gy × 2) in mice bearing breast tumors (4T1) [53].

Radiation has also been shown to modulate the expression of stress ligands that stimulate NK cell activation. These ligands (MICA/B and ULBP in humans and RAE-1 in mice) bind to NKG2D receptors on NK cells (and CD8+ T cells) and stimulate their lytic activity [72]. Kim et al. observed an increase in MICB and ULBP1/2 following 20 Gy radiation in various cancer cell lines (melanoma, colon, cervical and lung) [55]. Increased expression of RAE-1 has similarly been reported following in vivo RT of tumor bearing mice [53].

In addition to antigen presentation and activating signals to cytotoxic immune cells, the expression of mediators of effector activities such as death receptors, can also be modulated in tumor cells by IR. Chakraborty et al. observed a marked increase in surface Fas expression in MC38-CEA+ murine tumors treated with 8 Gy [56]. There are many reports of increased expression of Fas in human tumor cells as well [26,44,57–59]. Increased sensitivity to the receptors for TRAIL-mediated apoptosis has been reported post IR [73,74], and it has further been demonstrated that expression of both DR4 and DR5 can be modulated by radiation (2–10 Gy) in human tumor cells [59,60].

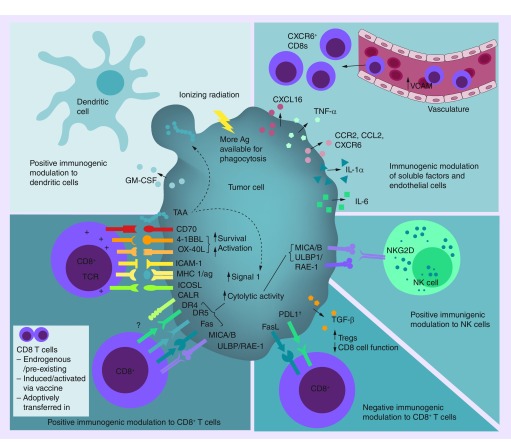

Cytokines can enhance immune activities of immune cells responding to tumor cells, and chemokines can facilitate the recruitment of immune cells into tumor tissue. IR can also modulate the expression of these molecules in tumor cells. Cytokines such as GM-CSF and IL-6 have been reported to be increased in the supernatants of two of three prostate cancer cell lines 48–72 h post IR (10 Gy) [51]. Another study reported an increase in the levels of GM-CSF, IL-1α and IL-6 in a human lung cancer cells line (AOI) 24 h post IR [62]. TNF-α was increased after treatment with 5 Gy in 5 of 13 human sarcoma cells [63]. Most recently, Wu and colleagues witnessed a significant increase in TGF-β1 in murine prostate cancer cells (TRAMP) both in vitro (6 Gy) and in vivo (10 Gy), suggesting that this immunosuppressive cytokine may also be induced from some tumors [61]. In addition to cytokines, IR can also alter the expression of chemokines from some tumor cells. The upregulation of CXCL16 (CXCR6 ligand) within tumors and blood vessels of 4T1 tumor-bearing mice following local irradiation (12 Gy × 2) in vivo has been demonstrated. CXCL16 is quickly shed by 4T1 tumor cells and markedly increased the recruitment of CXCR6+CD8+ T cells into the tumor [64]. A significant increase in CCR2 and CCL2 mRNA was observed in HPV-associated tumors of mice locally irradiated with 14Gy [65]. CCR2 mediates monocyte chemotaxis and CCL2 recruits monocytes, MDSCs and DCs to sites of tissue injury and inflammation. The authors also reported significant upregulation of CXCR6 (regulates metastasis and progression of cancer via interaction with soluble CXCL16) and CXCL16 (induces migration of several subsets of T cells and NK cells) after radiation. Collectively, these results reveal that hypo-fractionated doses of IR can modulate soluble signals that influence the behavior of diverse immune cells as well as chemokines and ligands involved in homing of immune cells. Overall, the reports of phenotypic changes induced in tumor cells receiving the doses of radiation discussed in this review are summarized in Figure 1, and are overwhelmingly positive in favor of promoting effective antitumor immune responses.

Figure 1. . Immunogenic modulation of tumor cells by ionizing radiation.

Tumors have been reported to be modulated in several ways, which could directly enhance the function, activity or recruitment of CD8+ T cells, as well as the function of NK and dendritic cells. Increased TAA could result in increased presentation on MHC-I to effector cytotoxic T lymphocytes but could also make more antigen available for uptake by antigen-presenting cells. There have also been limited reports of modulation of tumors in a manner that could negatively impact CD8+ T-cell activities. Note: Ionizing radiation-induced immunogenic cell death mechanisms that enhance dendritic cell activities are not depicted in this figure.

†PD-L1 has been reported to be both increased, and decreased, by ionizing radiation.

Ag: Antigen.

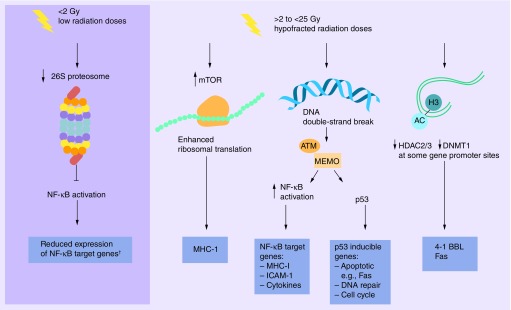

Mechanism of modulation in tumor cells within the hypofractionated dose range

NF-κB

Several mechanisms have been described for how IR can modulate expression of immune relevant genes in tumor cells (Figure 2). While LD-RT has been shown to reduce NF-κB via proteasome inhibition, hypofractionated doses of IR have conversely demonstrated increased activity of NF-κB. NF-κB can be activated in different cell types within an irradiated tumor mass including the tumor cells, stromal cells, cells of the vasculature, and immune cells. In tumor cells, genotoxic stress induced NF-kB activation is initiated by DNA double strand breaks (DSB) in the nucleus and can stimulate gene expression. NF-κB activation has been reported to occur in this manner in diverse tumor cell lines in an ATM-dependent pathway, mostly at doses above 3 Gy. ATM signaling alone is not sufficient; post-translational modification of NEMO is needed, and is also induced by IR. Fully composed ATM-NEMO complexes (reviewed in [30]) can phosphorylate IkB resulting in its degradation by the 26S proteasome. This frees NF-κB to translocate into the nucleus and activate NF-κB target genes. Subsequent expression of NF-κB-induced cytokines can sustain this signaling pathway in a positive feed forward loop. Not surprisingly, some of the genes modulated by IR in tumor cells, as mentioned above, are known NF-κB target genes (MHC-I, ICAM1, cytokines) [30]. ATM signaling is also a well-known activator of p53. p53 target genes, however, are related mostly to cell cycle, apoptosis and DNA repair pathways (reviewed in [75]). While most p53 inducible genes are not typical immune relevant genes, apoptosis inducing death receptors could be important for immune cell mediated signals transmitted from death ligands on cytotoxic immune cell. Unfortunately, less than 50% of tumor cells retain functional p53.

Figure 2. . Diverse mechanisms of immunogenic modulation reported in tumor cells surviving radiation.

†NF-κB has been reported to be both inhibited and activated at lower radiation doses depending upon tissue and length of exposure.

mTOR

While NF-κB may be responsible for MHC-I upregulation early post IR, the kinase mTOR has been shown to be responsible for the radiation-induced increase in MHC-I expression at later times post IR (24 h) [21]. mTOR is a critical regulator of protein translation by causing enhanced ribosomal translation. As overall translation is increased, so is the intracellular pool of peptides available for binding to MHC-I. This increase in peptides appears to be responsible for the increased MHC. Interestingly, the benefit of combination immunotherapy with RT was lost when an mTOR inhibitor was utilized demonstrating the therapeutic relevance of this pathway post IR [74].

Epigenetic

It has recently been reported that IR-induced DNA hypomethylation induced gene expression in CRC cells treated with 2–5 Gy [76]. Our studies have found that increased 4–1BBL expression following 10 Gy radiation is mediated by increased histone acetylation at the promoter for this gene in human CRC cells [48]. More recently, we have reported that radiation (5 Gy) similarly increases histone acetylation at both the Fas and DR5 promoters in addition to the 4–1BBL promoter. Further, less HDAC2, HDAC3 and DNMT1 were bound to the promoter regions of both 4–1BBL and Fas, but not other genes following IR of human tumor cells [77]. These observations suggest that radiation can also regulate the expression of specific genes by epigenetic mechanisms. This could be important for combination radiation-immunotherapy approaches, as epigenetic changes can be maintained for quite some time in the cell population. At this time, it is unclear how IR is altering the binding of these enzymes at specific gene promoters.

miRNAs

miRNAs are key regulators of gene expression. Several miRNAs have been reported to be modulated following exposure to IR [78,79]. There is also evidence for regulation of gene expression via miRNAs in normal endothelial cells exposed to IR [80]. Interestingly, miR16 was shown to be downregulated following exposure to IR (10 Gy delivered in fractions), and 4-1BBL (TNFSF9) was identified as one of the target genes whose expression was increased in response to this miRNAs reduction. If this same mechanism of regulation operates in irradiated tumor cells needs to be determined. These data highlight the fact that molecules co-stimulatory to effector T cells seem to be induced by radiation in a variety of cell types, including both normal and tumor.

Modulation of immune cells within the hypofractionated dose range

Cells of the immune system can be rapidly dividing, and therefore vulnerable to radiation. Individuals receiving heavy doses of radiation (atomic bomb survivors) exhibit severe damage to mature lymphocytes and bone marrow stem cells, resulting in depletion of several immune cell subsets [81]. This has led to the long-standing perception that radiation beyond the low dose range is generally immune suppressive. In recent years, however, there have been several reports of higher dose radiation treatment directly modulating the phenotype of immune cells both positively and negatively.

Evidence demonstrating positive modulation of immune cells, in a manner that would make them more effective for antitumor activity, has been accumulating and is summarized in Table 2. For example, Huang et al. observed the upregulation of CD70 on mature dendritic cells and CD20+ B cells isolated for human PBMCs following exposure to 10 Gy in vitro [66]. Further analysis showed no change in CD80 and CD86 expression or the maturation marker CD83 on DCs. Irradiation of DCs also increased IL-12 and IL-23 cytokine secretion with doses as high as 10 Gy and 20 Gy, respectively. Following local irradiation (10 Gy) of mice bearing B16 tumors, Gupta et al. detected significant upregulation of CD70 and CD86 on live DCs (CD45+CD11chighMHC-IIhigh) by flow cytometry 48 h post RT [67]. Radiation has also been reported to increase markers of activation in monocytes [68]. In vitro treatment with 20 Gy (and 2 Gy to a lesser degree) induced significantly higher expression of CD40, MHC-II (HLA-DR) and CD86 48 h post IR on the monocyte cell line U937 in an NF-κB dependent manner. APCs modulated in such ways would be better able to stimulate subsequent antitumor immune responses.

Conflicting data exist regarding the radiosensitivity of different subsets of lymphocytes. Thus, it is very important to elucidate how different components of the immune system are altered by IR. In particular, there are many conflicting reports on the impact of radiation on CD4+ TREGS, which play a major role in immune tolerance [82]. In cancer patients, TREGS inhibit the generation of successful antitumor immune responses and increased infiltration of TREGS is often detected within the TME [83,84]. One study suggests that irradiation may modulate the phenotype (and function) of human TREGS in vitro [69]. CD4+CD25+ TREGS from PBMCs were irradiated and evaluated for expression of TREG specific markers. There was reduced expression of CD62L, FOXP3 and CD45RO and increased expression of GITR 12 h post irradiation (1.875, 7.5 and 30 Gy). By contrast, there was no change in the expression of CD4, CD28 and CD45RA on TREGS. The expression of membrane TGF-β, a suppressive effector molecule of TREGS, was also decreased after irradiation of TREGS with 30 Gy as compared with nonirradiated TREGS. Here, reduced expression of TREG effector molecules could correlate with reduced suppressive activity thus allowing effective antitumor immune responses.

There have also been reports of radiation modulating immune cells in a manner that could be inhibitory to effective antitumor immune responses. After exposing TUBO breast cancer cells to 12 Gy RT, PD-L1 expression was increased in DCs after 72 h [85]. There was also a slight increase in PD-L1 seen on macrophages but no observable change in MDSC expression of PD-L1. Curiously, PD-1 expression on CD8+ T cells was slightly reduced 3 days post-irradiation in this same study. It is unclear, however, if this was direct modulation by RT or modulation in response to factors produced by other cells in the local environment. Irradiation of mice bearing murine prostate tumors (TRAMP-C1) induced phenotypic changes in macrophages associated with cancer promotion [70]. Higher dose RT with 25 Gy induced increased arginase and COX-2 and promoted tumor growth [70]. iNOS was produced at later times in these cells and at low levels. This is the opposite of findings discussed above, by Klug et al. using LD-RT, and highlights the importance of understanding the impact of IR dose on immune cell activities. The impact of radiation specifically on MDSC phenotype has not been extensively studied, but there are reports of both expansion [86] and reduction [87] in MDSC numbers post IR.

• Immunomodulation at work (functional outcomes)

In vitro evidence of IM & functional enhancement of cytotoxic immune cells

It is clear that there is much more to RT than its traditional use for direct tumor cell destruction or palliation of pain. IR has the ability to modulate gene expression in tumor cells in ways that make them better stimulators of immune cell function [9]. This ability of IR has been demonstrated in several in vitro model systems where the function of immune cells is enhanced as a direct consequence of interactions with irradiated tumor cells. Sublethal irradiation of colorectal carcinoma cells (CRC) lines resulted in enhanced susceptibility to lysis by tumor specific CTLs following 10 Gy of irradiation [44]. CTL killing was MHC restricted as irradiated MHC mismatched CRC were not killed by the TAA specific T cells. Moreover, increased killing by CTLs was also observable against other cancer types including prostate [47] and head neck squamous carcinoma [52], revealing that enhanced killing of irradiated tumor cells is not restricted to a single cancer type. More recently we have reported that interaction of CTLs with irradiated human CRC cells enhances the survival and activation of T cells [48]. Enhanced CTL function against irradiated tumor cells is not limited to EBRT, as Chakraborty et al. have reported that exposure to 153Sm-EDTMP enhanced CTL killing of irradiated prostate tumor cells (LNCaP) [46]. Despite different molecular profiles of IM, studies by Gameiro and colleagues reveal that radiation-induced tumor sensitivity to CTL lysis was equally augmented with single or fractionated doses of radiation, suggesting that either regimen could elicit effective attack by T cells [47]. In addition to modulated tumor cells, immune cells modulated by RT also have the ability to enhance T cell function. For example, irradiated DCs have been shown to increase the proliferation and IFN-γ production from T cells as a direct consequence of increased expression of CD70 [66]. There is also some evidence that the ability of TREGS to suppress cells is reduced following both high-dose [69] and low-dose irradiation in vitro [39].

IM of tumor cells by RT has also been shown to enhance functional activity of NK cells. NK cell-mediated recognition and cytolysis of human tumor cells is governed by ligation of the NKG2D receptor on NK cells with MICA and MICB (MICA/B) molecules on tumor cells. Human melanoma cells and non-small-cell lung cancer cell lines that increase expression of MICA/MICB after 20 Gy IR also exhibited enhanced sensitivity to NK mediated killing [55]. Liu et al. reported that upregulation of MICA/B on the tumor cell surface led to increased recruitment, activation and survival of NK cells [25]. Direct exposure of human NK cells to radiation can result in increased NK cytotoxicity that seems to peak at an optimal dose (6 Gy) and decline after the peak (range: 1–16 Gy). Radiation-treated NK cells from cancer patients have been reported to have higher lytic activity than NK cells from normal controls [88]. Radiation also enhanced the cytotoxic effects of NK cells when they were inoculated, as a mixture with tumor cells, into mice after irradiation [89]. This synergistic effect was not observed when the lymphoid cells were inoculated after irradiation, indicating that lymphoid cells needed to be in contact with tumor cells before irradiation. Anti-asialo GM1 reversed this effect implicating NK cells as the effectors here. Purified NK cells exposed to 0.2 Gy LD-RT in vitro displayed no significant difference in cell viability or proliferation. However, significant augmentation of cytotoxic function was detected when NK cells were stimulated with low-dose IL-2 prior to irradiation [90]. Others have similarly reported that radiation-treated NK cells exhibit increased function [91–93]. Collectively, these studies demonstrate the ability of IR to enhance NK cell activity by both direct treatment with IR and as a consequence of radiation-induced IM of the tumor.

In vivo evidence of IM & functional enhancement of cytotoxic immune cells

All cells in the TME, including the target tumor cells, endothelial cells, stromal cells and infiltrating immune cells, may respond uniquely and further influence the response of neighboring cells. While immune cells are thought to be more radiosensitive than other cells in the TME, there are numerous accounts of local tumor irradiation in vivo culminating in effective immune attack of tumors by both adaptive and innate cells. RT has been shown to enhance tumor-specific CTL numbers and function in the intact TME. Chakraborty et al. demonstrated enhanced killing of CEA+MC38 tumors by CEA specific CD8+ T cells in mice irradiated with 8 Gy. The ability of RT to enhance attack of tumor cells was demonstrated using both a therapeutic vaccine to induce T cell expansion [94] as well as when tumor specific T cells were adoptively transferred into the animals [56]. In the latter study, modulation of the Fas receptor on tumor cells was shown to be required for the ability of RT to enhance immune attack. Using another tumor model system, adoptive cell transfer of ex vivo activated OVA-specific OT-1 CD8+ T cells led to increased infiltration of transferred T cells to tumor sites (and not merely expansion of localized T cells) following RT (15 Gy) to the tumor [95]. This study suggested that the mechanism of radiation-induced lymphocyte infiltration into the TME involved upregulation of chemo-attractants MIG and IP-10. Though it was not determined which cells were producing these factors, these chemo-attractants appeared to promote IFN-γ responses by conditioning the tumor microenvironment for enhanced CTL trafficking. Moreover, the tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) isolated from in vivo irradiated tumors killed better than TILs from nonirradiated hosts.

There are similar reports of radiation modulating tumor cells in vivo and enhancing tumor-specific NK cell numbers and function. Ruocco et al. demonstrated that RT (12 Gy × 2) synergized with CTLA-4 blockade by upregulating RAE-1 expression on the surface of irradiated tumor cells and that the therapeutic effect of the combinatorial regimen were blocked by antibodies targeting the RAE-1 receptor (NKG2D) [53]. IL-12/1L-15/1L-18 preactivated NK cells showed increased frequencies and persistent effector functions inside established murine tumors following RT (5 Gy TBI), highlighting the enhanced therapeutic efficacy of combination NK cell therapy and RT [96]. In patients, NK cells from uterine cervix carcinoma patients undergoing radiotherapy demonstrated increased cytotoxicity, suggesting that it is possible for RT to enhance immune cell function in the human TME [97].

RT can also influence other noncytotoxic immune cells in a way that could positively influence antitumor attack. There have been limited reports of RT, in the dose ranges discussed here, modulating APCs in the TME to enhance cross-presentation of TAA [98] or recruiting additional immune cells including CD8+ T cells into the TME [99]. TREG mediated suppressive activity from irradiated (8.5 Gy) melanoma (D5) tumor bearing mice has been reported to be significantly reduced when compared with TREGS from untreated mice indicating that RT impairs function of TREGS [100]. However, there have also been contrasting reports revealing that RT (10 Gy) can induce suppressive immune cells following local RT to some tumors (TRAMP) [61]. Thus, it remains unresolved if IM of tumors by radiation can directly influence TREG number and function.

Conclusion

The most exciting reports of RT-CIT in combination have been of the abscopal response following RT both preclinically [101,102] and clinically [12–16,103]. The abscopal response likely involves cytolytic cells that retain the functional ability to mount a sustained response at a distant, nonmodulated, tumor site. The mechanism(s) of the abscopal effect has not been definitively determined. Molecules that can alter the lytic capacity or enhance the sustainability of effector CTLs or NK cells are likely candidates for promoting this type of effect. For a long time increased expression of death receptors such as Fas was thought to be the sole molecular mechanism responsible for enhanced immune attack of irradiated tumors [56]. However, very simple in vitro systems demonstrated that human tumor cells with deficient Fas signaling were still killed better by CTLs after radiation suggested that alternate mechanisms exist and contribute to this effect [44]. Use of these in vitro systems has allowed us to directly test the impact of irradiated tumors on CTL biology, and has revealed that CTLs also survive better and are activated better following interaction with irradiated tumor cells [48]. Examination of irradiated tumor cells for changes in expression of genes that could provide survival, activation and enhanced lytic activity in effector CTLs revealed that the co-stimulatory molecules OX-40L and 4–1BBL were upregulated on irradiated tumor cells [48,49]. Increased MHC-I and antigen expression following IR have been demonstrated by several groups. Increased signal 1, however, must work in concert with other signals to T cells. Increased antigen in a toleragenic or immunosuppressive environment where robust costimulation is not present leads to suboptimal immune responses such as T-cell anergy. Thus, many proposed mechanisms of RT-enhanced immune responses (more antigen presentation, immunogenic death, increased death receptor, increased stress ligands or increased cell adhesion expression) would still require appropriate co-stimulation to induce optimal and sustainable CTL responses. Furthermore, these changes all occur local to the irradiated tumor and it is difficult to envision how many of the reported changes at the local irradiated tumors could promote a response that is sustainable at a distant tumor unless the change was retained within the responding effector cells. Receiving signals from OX-40L or 4–1BBL, or perhaps effector activity programming cytokines, from irradiated tumor cells could leave a lasting impression on T cells leaving the tumor and impact future activity beyond the irradiated tumor [104,105]. This argument seems plausible given the fact that the mere presence of antigen specific T cells (or induction of greater numbers by vaccine) is not enough to induce curative T cell activity against many tumors. Indeed, there are situations where T cells of known TAA-specificity already exist but are not effectively attacking the tumor, even when large numbers are transferred into tumor bearing hosts [56]. In these situations radiation is not needed to ‘prime’ an initial T cell response to the TAA via ICD because large numbers of effector cells are being transferred in. Local RT does, however, result in greatly enhanced activity of T cells suggesting that the existing T cells may now be receiving different signals from the irradiated tumor [43,106]. Moreover, irradiated tumor cells alone, and in the absence of APCs, are killed better by effector CTLs [44,46–47,52], and are able to enhance T cell survival and activation [48]. This mechanism would be relevant when effector CTLs are already present but have less than optimal functional or killing capacity.

At this time, RT is routinely applied for palliation or tumor debulking in patients where it is not curative. Given the substantial evidence of the IM activities of IR, perhaps now is the time to begin utilizing RT specifically for IM in combo with CIT strategies. Though this review focused on radiation doses of 25 Gy or below, the influence of various doses within this range should be considered a critical factor moving forward [107,108] in defining the most effective dose for promoting IM activities. For example, NK cells are sensitive to high doses of radiation while lower dose radiation enhances cytotoxicity of NK cells [93]. Lower doses may help achieve a more favorable balance between tumor-infiltrating cytotoxic cells, and the unfavorable suppressive cells, allowing for tumor elimination [109]. Many RT-CIT studies use much higher doses (>25 Gy total) [87,110–111], and it is unclear if the immune outcomes reported occur similarly at lower doses. To this point, many differences are seen in the modulation of MHC-I following low dose [45] versus higher dose [112]. Lower doses may also be fundamentally better for use as an adjuvant to CIT because of lower toxicity as well as reduced clinical visits for the patient. In addition to dose range, single dose delivery versus multiple fraction delivery seem to differentially influence IM outcomes [19,20].

Future perspective

What is next regarding immunomodulation and radiation therapy for cancer? IM-induced phenotypic changes in tumor cells have been studied extensively. However, given the differential radio-sensitivities of immune cell subsets, it seems imperative to more fully elucidate the direct effects of LD-RT and radiation doses within the hypofractionated dose range on immune cell function. It will also be important to determine which phenotypic changes occur most broadly and can thus be capitalized on across diverse human tumor types. Regarding the TME, how stromal cells and local endothelial cells are modulated and contribute to antitumor activity or immune suppression at these doses needs to be elucidated both in vitro and in vivo. Given the recent evidence that IM of some genes is occurring via epigenetic mechanisms, determining how long these changes are retained in tumor cells as well as what other immune relevant genes are regulated this way will be helpful for defining the therapeutic usefulness of RT-induced IM. It is perhaps most important to determine which changes occur in instances where abscopal responses are seen. The mechanisms reported for induction of the abscopal effect are diverse, coming from both tumor immunologists and radiation biologists, and it will be important to define which mechanism(s) are at play at these doses so that we can induce this type of response more consistently. Last, which of the many and diverse immunotherapies (checkpoint blockade, therapeutic vaccines, positive co-stimulatory agonist abs, adoptive cell transfer, TLR agonists, among others) will benefit the most from the IM action of RT needs to be defined. Overall, such data will allow for determination of which CITs should routinely incorporate RT for its IM activities, and at what dose, allowing for the rationale incorporation of RT into CIT approaches.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY.

Immunomodulation by low-dose radiotherapy

Low-dose radiotherapy (LD-RT) can modulate tumor phenotype.

Immune cells can be directly modulated by LD-RT in ways that have been reported to be beneficial for antitumor efficacy.

Single dose LD-RT inhibits NF-κB-mediated gene expression via proteasome inhibition.

LD-RT and hypofractionated doses of RT appear to modulate NF-κB activity via different mechanisms in tumor cells.

Immunomodulation by hypofractionated doses of radiation

Single dose RT (8–10 Gy) has been shown to modulate phenotype in vitro resulting in enhanced function of effector cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs).

Tumors irradiated with 10 Gy single dose (SD) enhance effector CTL viability and activity.

Single dose RT in the hypofractionated dose range has been demonstrated to modulate tumor phenotype and gene expression by several diverse mechanisms.

Antigen-presenting cells and TREGS exposed to SD radiation appear to be modulated in ways that could enhance the activities of cytotoxic immune cells.

Immunomodulation at work (functional outcomes)

SD RT (8–10 Gy) has been shown to modulate phenotype in vivo and result in enhanced function of transferred CTLs and NK cells.

10 Gy SD can synergize with therapeutic cancer vaccines to induce an abscopal response.

In vivo, RT has been shown to influence other noncytotoxic immune cells in a way that could positively influence antitumor attack by effector cells.

Footnotes

Financial & competing interest disclosure

C Garnett-Benson has been the recipient of an R21 from the NCI on radiation and TREG cells (CA162235) and has a pending Research Scholar Grant on radiation and immunotherapy from the American Cancer Society. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

Proofreading and editing services of Melissa Heffner of Second Look were utilized for the final manuscript production (funded by Georgia State University Department of Biology Internal Bridge Award).

References

Papers of special note have been highlighted as: • of interest; •• of considerable interest

- 1.Formenti SC, Demaria S. Combining radiotherapy and cancer immunotherapy: a paradigm shift. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105(4):256–265. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djs629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Panaretakis T, Kepp O, Brockmeier U, et al. Mechanisms of pre-apoptotic calreticulin exposure in immunogenic cell death. EMBO J. 2009;28(5):578–590. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kroemer G, Galluzzi L, Kepp O, Zitvogel L. Immunogenic cell death in cancer therapy. Ann. Rev. Immunol. 2013;31:51–72. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032712-100008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Park B, Yee C, Lee KM. The effect of radiation on the immune response to cancers. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014;15(1):927–943. doi: 10.3390/ijms15010927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Golden EB, Pellicciotta I, Demaria S, Barcellos-Hoff MH, Formenti SC. The convergence of radiation and immunogenic cell death signaling pathways. Front. Oncol. 2012;2:88. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2012.00088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Apetoh L, Tesniere A, Ghiringhelli F, Kroemer G, Zitvogel L. Molecular interactions between dying tumor cells and the innate immune system determine the efficacy of conventional anticancer therapies. Cancer Res. 2008;68(11):4026–4030. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tesniere A, Panaretakis T, Kepp O, et al. Molecular characteristics of immunogenic cancer cell death. Cell Death Differ. 2008;15(1):3–12. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hodge JW, Kwilas A, Ardiani A, Gameiro SR. Attacking malignant cells that survive therapy: exploiting immunogenic modulation. Oncoimmunology. 2013;2(12):e26937. doi: 10.4161/onci.26937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wattenberg MM, Fahim A, Ahmed MM, Hodge JW. Unlocking the combination: potentiation of radiation-induced antitumor responses with immunotherapy. Radiat. Res. 2014;182(2):126–138. doi: 10.1667/RR13374.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shahabi V, Postow MA, Tuck D, Wolchok JD. Immune-priming of the tumor microenvironment by radiotherapy: rationale for combination with immunotherapy to improve anticancer efficacy. Am. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015;38(1):90–97. doi: 10.1097/COC.0b013e3182868ec8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sharabi AB, Tran PT, Lim M, Drake CG, Deweese TL. Stereotactic radiation therapy combined with immunotherapy: augmenting the role of radiation in local and systemic treatment. Oncology (Williston Park) 2015;29(5):331–340. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Postow MA, Callahan MK, Barker CA, et al. Immunologic correlates of the abscopal effect in a patient with melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012;366(10):925–931. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1112824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stamell EF, Wolchok JD, Gnjatic S, Lee NY, Brownell I. The abscopal effect associated with a systemic anti-melanoma immune response. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2013;85(2):293–295. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2012.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Golden EB, Demaria S, Schiff PB, Chachoua A, Formenti SC. An abscopal response to radiation and ipilimumab in a patient with metastatic non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2013;1(6):365–372. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-13-0115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• This was the first study to administer local radiotherapy (RT) to a metastatic lesion in a treatment-refractory lung cancer patient with the intent to induce an abscopal response.

- 15.Golden EB, Chhabra A, Chachoua A, et al. Local radiotherapy and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor to generate abscopal responses in patients with metastatic solid tumours: a proof-of-principle trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(7):795–803. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00054-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hiniker SM, Chen DS, Reddy S, et al. A systemic complete response of metastatic melanoma to local radiation and immunotherapy. Transl. Oncol. 2012;5(6):404–407. doi: 10.1593/tlo.12280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garnett-Benson C, Hodge JW, Gameiro SR. Combination regimens of radiation therapy and therapeutic cancer vaccines: mechanisms and opportunities. Semin. Radiat. Oncol. 2015;25(1):46–53. doi: 10.1016/j.semradonc.2014.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Disis ML. Mechanism of action of immunotherapy. Semin. Oncol. 2014;41(Suppl. 5):S3–S13. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2014.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Makinde AY, John-Aryankalayil M, Palayoor ST, Cerna D, Coleman CN. Radiation survivors: understanding and exploiting the phenotype following fractionated radiation therapy. Mol. Cancer Res. 2013;11(1):5–12. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-12-0492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Demaria S, Formenti SC. Radiation as an immunological adjuvant: current evidence on dose and fractionation. Front. Oncol. 2012;2:153. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2012.00153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reits EA, Hodge JW, Herberts CA, et al. Radiation modulates the peptide repertoire, enhances MHC class I expression, and induces successful antitumor immunotherapy. J. Exp. Med. 2006;203(5):1259–1271. doi: 10.1084/jem.20052494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • This report demonstrated enhanced translation due to activation of the mTOR pathway that resulted in increased peptide production, antigen presentation and cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) recognition of irradiated cells.

- 22.Liao YP, Wang CC, Butterfield LH, et al. Ionizing radiation affects human MART-1 melanoma antigen processing and presentation by dendritic cells. J. Immunol. 2004;173(4):2462–2469. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.4.2462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sharma A, Bode B, Wenger RH, et al. Gamma-radiation promotes immunological recognition of cancer cells through increased expression of cancer-testis antigens in vitro and in vivo . PLoS ONE. 2011;6(11):e28217. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gasser S, Raulet DH. Activation and self-tolerance of natural killer cells. Immunol. Rev. 2006;214:130–142. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2006.00460.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu C, Suksanpaisan L, Chen YW, Russell SJ, Peng KW. Enhancing cytokine-induced killer cell therapy of multiple myeloma. Exp. Hematol. 2013;41(6):508–517. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2013.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sheard MA, Krammer PH, Zaloudik J. Fractionated gamma-irradiation renders tumour cells more responsive to apoptotic signals through CD95. Br. J. Cancer. 1999;80(11):1689–1696. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Abdulkarim B, Sabri S, Deutsch E, et al. Radiation-induced expression of functional Fas ligand in EBV-positive human nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells. Int. J. Cancer. 2000;86(2):229–237. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(20000415)86:2<229::aid-ijc12>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Trott KR. Therapeutic effects of low radiation doses. Strahlenther. Onkol. 1994;170(1):1–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hildebrandt G, Seed MP, Freemantle CN, Alam CA, Colville-Nash PR, Trott KR. Mechanisms of the anti-inflammatory activity of low-dose radiation therapy. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 1998;74(3):367–378. doi: 10.1080/095530098141500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hellweg CE. The Nuclear Factor kappaB pathway: a link to the immune system in the radiation response. Cancer Lett. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2015.02.019. doi:10.1016/j.canlet.02.019. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pore N, Gupta AK, Cerniglia GJ, et al. Nelfinavir down-regulates hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha and VEGF expression and increases tumor oxygenation: implications for radiotherapy. Cancer Res. 2006;66(18):9252–9259. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang G, Kong Q, Wang G, et al. Low-dose ionizing radiation induces direct activation of natural killer cells and provides a novel approach for adoptive cellular immunotherapy. Cancer Biother. Radiopharm. 2014;29(10):428–434. doi: 10.1089/cbr.2014.1702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ren H, Shen J, Tomiyama-Miyaji C, et al. Augmentation of innate immunity by low-dose irradiation. Cell Immunol. 2006;244(1):50–56. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2007.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Klug F, Prakash H, Huber PE, et al. Low-dose irradiation programs macrophage differentiation to an iNOS(+)/M1 phenotype that orchestrates effective T cell immunotherapy. Cancer Cell. 2013;24(5):589–602. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lodermann B, Wunderlich R, Frey S, et al. Low dose ionising radiation leads to a NF-kappaB dependent decreased secretion of active IL-1beta by activated macrophages with a discontinuous dose-dependency. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 2012;88(10):727–734. doi: 10.3109/09553002.2012.689464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wunderlich R, Ernst A, Rodel F, et al. Low and moderate doses of ionizing radiation up to 2 Gy modulate transmigration and chemotaxis of activated macrophages, provoke an anti-inflammatory cytokine milieu, but do not impact upon viability and phagocytic function. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2015;179(1):50–61. doi: 10.1111/cei.12344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu SZ, Jin SZ, Liu XD, Sun YM. Role of CD28/B7 costimulation and IL-12/IL-10 interaction in the radiation-induced immune changes. BMC Immunol. 2001;2:8. doi: 10.1186/1471-2172-2-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shigematsu A, Adachi Y, Koike-Kiriyama N, et al. Effects of low-dose irradiation on enhancement of immunity by dendritic cells. J. Radiat. Res. 2007;48(1):51–55. doi: 10.1269/jrr.06048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang B, Li B, Dai Z, et al. Low-dose splenic radiation inhibits liver tumor development of rats through functional changes in CD4+CD25+Treg cells. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2014;55:98–108. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2014.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Farooque A, Mathur R, Verma A, et al. Low-dose radiation therapy of cancer: role of immune enhancement. Expert Rev. Anticancer Ther. 2011;11(5):791–802. doi: 10.1586/era.10.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sanfilippo NJ, Cooper BT. Hypofractionated radiation therapy for prostate cancer: biologic and technical considerations. Am. J. Clin. Exp. Urol. 2014;2(4):286–293. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mangoni M, Desideri I, Detti B, et al. Hypofractionation in prostate cancer: radiobiological basis and clinical appliance. Biomed. Res. Int. 2014;2014:781340. doi: 10.1155/2014/781340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lugade AA, Moran JP, Gerber SA, Rose RC, Frelinger JG, Lord EM. Local radiation therapy of B16 melanoma tumors increases the generation of tumor antigen-specific effector cells that traffic to the tumor. J. Immunol. 2005;174(12):7516–7523. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.12.7516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Garnett CT, Palena C, Chakraborty M, Tsang KY, Schlom J, Hodge JW. Sublethal irradiation of human tumor cells modulates phenotype resulting in enhanced killing by cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Cancer Res. 2004;64(21):7985–7994. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • This report demonstrated that a panel of human tumor cells, including some with defective Fas signaling, was more sensitive to lysis by CTLs after single dose RT.

- 45.Newcomb EW, Demaria S, Lukyanov Y, et al. The combination of ionizing radiation and peripheral vaccination produces long-term survival of mice bearing established invasive GL261 gliomas. Clin. Cancer Res. 2006;12(15):4730–4737. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chakraborty M, Wansley EK, Carrasquillo JA, et al. The use of chelated radionuclide (samarium-153-ethylenediaminetetramethylenephosphonate) to modulate phenotype of tumor cells and enhance T cell-mediated killing. Clin. Cancer Res. 2008;14(13):4241–4249. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gameiro SR, Jammeh ML, Wattenberg MM, Tsang KY, Ferrone S, Hodge JW. Radiation-induced immunogenic modulation of tumor enhances antigen processing and calreticulin exposure, resulting in enhanced T-cell killing. Oncotarget. 2014;5(2):403–416. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.1719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• This is the first paper to report that RT-induced CALR expression could enhanced CTL cytolysis of tumor cells and suggests an antigen-presenting cell-independent role for CALR.

- 48.Kumari A, Cacan E, Greer SF, Garnett-Benson C. Turning T cells on: epigenetically enhanced expression of effector T-cell costimulatory molecules on irradiated human tumor cells. J. Immunother. Cancer. 2013;1:17. doi: 10.1186/2051-1426-1-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• This report demonstrates that irradiated tumor cells are not passive targets, and can alter the biology of responding effector T cells by modulating expression of proteins that enhance T-cell activation and survival.

- 49.Bernstein MB, Garnett CT, Zhang H, et al. Radiation-induced modulation of costimulatory and coinhibitory T-cell signaling molecules on human prostate carcinoma cells promotes productive antitumor immune interactions. Cancer Biother. Radiopharm. 2014;29(4):153–161. doi: 10.1089/cbr.2013.1578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Deng L, Liang H, Burnette B, Weicheslbaum RR, Fu YX. Radiation and anti-PD-L1 antibody combinatorial therapy induces T cell-mediated depletion of myeloid-derived suppressor cells and tumor regression. Oncoimmunology. 2014;3:e28499. doi: 10.4161/onci.28499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Aryankalayil MJ, Makinde AY, Gameiro SR, et al. Defining molecular signature of pro-immunogenic radiotherapy targets in human prostate cancer cells. Radiat. Res. 2014;182(2):139–148. doi: 10.1667/RR13731.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gelbard A, Garnett CT, Abrams SI, et al. Combination chemotherapy and radiation of human squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck augments CTL-mediated lysis. Clin. Cancer Res. 2006;12(6):1897–1905. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ruocco MG, Pilones KA, Kawashima N, et al. Suppressing T cell motility induced by anti-CTLA-4 monotherapy improves antitumor effects. J. Clin. Invest. 2012;122(10):3718–3730. doi: 10.1172/JCI61931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Behrends U, Peter RU, Hintermeier-Knabe R, et al. Ionizing radiation induces human intercellular adhesion molecule-1 in vitro . J. Invest. Dermatol. 1994;103(5):726–730. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12398607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kim JY, Son YO, Park SW, et al. Increase of NKG2D ligands and sensitivity to NK cell-mediated cytotoxicity of tumor cells by heat shock and ionizing radiation. Exp. Mol. Med. 2006;38(5):474–484. doi: 10.1038/emm.2006.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chakraborty M, Abrams SI, Camphausen K, et al. Irradiation of tumor cells up-regulates Fas and enhances CTL lytic activity and CTL adoptive immunotherapy. J. Immunol. 2003;170(12):6338–6347. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.12.6338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • This was the first report of the direct ability of in vivo RT to modulate expression of a gene that directly enhanced tumor cell susceptibility to cytolysis by CTLs.

- 57.Sheard MA, Vojtesek B, Janakova L, Kovarik J, Zaloudik J. Up-regulation of Fas (CD95) in human p53wild-type cancer cells treated with ionizing radiation. Int. J. Cancer. 1997;73(5):757–762. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19971127)73:5<757::aid-ijc24>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rigberg DA, Centeno J, Kim FS, et al. Irradiation-induced up-regulation of Fas in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma is not accompanied by Fas ligand-mediated apoptosis. J. Surg. Oncol. 1999;71(2):91–96. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9098(199906)71:2<91::aid-jso6>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ifeadi V, Garnett-Benson C. Sub-lethal irradiation of human colorectal tumor cells imparts enhanced and sustained susceptibility to multiple death receptor signaling pathways. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(2):e31762. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Marini P, Schmid A, Jendrossek V, et al. Irradiation specifically sensitises solid tumour cell lines to TRAIL mediated apoptosis. BMC Cancer. 2005;5:5. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-5-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wu CT, Hsieh CC, Yen TC, Chen WC, Chen MF. TGF-beta1 mediates the radiation response of prostate cancer. J. Mol. Med. 2015;93(1):73–82. doi: 10.1007/s00109-014-1206-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhang JS, Nakatsugawa S, Niwa O, Ju GZ, Liu SZ. Ionizing radiation-induced IL-1 alpha, IL-6 and GM-CSF production by human lung cancer cells. Chin. Med. J. 1994;107(9):653–657. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hallahan DE, Spriggs DR, Beckett MA, Kufe DW, Weichselbaum RR. Increased tumor necrosis factor alpha mRNA after cellular exposure to ionizing radiation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1989;86(24):10104–10107. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.24.10104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Matsumura S, Wang B, Kawashima N, et al. Radiation-induced CXCL16 release by breast cancer cells attracts effector T cells. J. Immunol. 2008;181(5):3099–3107. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.5.3099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • This report initiated the present concept of immunogenic modulation of tumors by demonstrating that irradiated tumors could express proteins that would enhance recruitment and activities of effector T cells in irradiated tumors.

- 65.Draghiciu O, Walczak M, Hoogeboom BN, et al. Therapeutic immunization and local low-dose tumor irradiation, a reinforcing combination. Int. J. Cancer. 2014;134(4):859–872. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Huang J, Wang QJ, Yang S, et al. Irradiation enhances human T-cell function by upregulating CD70 expression on antigen-presenting cells in vitro . J. Immunother. 2011;34(4):327–335. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e318216983d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gupta A, Probst HC, Vuong V, et al. Radiotherapy promotes tumor-specific effector CD8+ T cells via dendritic cell activation. J. Immunol. 2012;189(2):558–566. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1200563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Parker JJ, Jones JC, Strober S, Knox SJ. Characterization of direct radiation-induced immune function and molecular signaling changes in an antigen presenting cell line. Clin. Immunol. 2013;148(1):44–55. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2013.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cao M, Cabrera R, Xu Y, Liu C, Nelson D. Gamma irradiation alters the phenotype and function of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells. Cell Biol. Int. 2009;33(5):565–571. doi: 10.1016/j.cellbi.2009.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Tsai CS, Chen FH, Wang CC, et al. Macrophages from irradiated tumors express higher levels of iNOS, arginase-I and COX-2, and promote tumor growth. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2007;68(2):499–507. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.01.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kober J, Leitner J, Klauser C, et al. The capacity of the TNF family members 4-1BBL, OX40L, CD70, GITRL, CD30L and LIGHT to costimulate human T cells. Eur. J. Immunol. 2008;38(10):2678–2688. doi: 10.1002/eji.200838250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Verneris MR, Karimi M, Baker J, Jayaswal A, Negrin RS. Role of NKG2D signaling in the cytotoxicity of activated and expanded CD8+ T cells. Blood. 2004;103(8):3065–3072. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-06-2125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Niyazi M, Marini P, Daniel PT, Humphreys R, Jendrossek V, Belka C. Efficacy of triple therapies including ionising radiation, agonistic TRAIL antibodies and cisplatin. Oncol. Rep. 2009;21(6):1455–1460. doi: 10.3892/or_00000374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Verbrugge I, Wissink EH, Rooswinkel RW, et al. Combining radiotherapy with APO010 in cancer treatment. Clin. Cancer Res. 2009;15(6):2031–2038. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-2125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Criswell T, Leskov K, Miyamoto S, Luo G, Boothman DA. Transcription factors activated in mammalian cells after clinically relevant doses of ionizing radiation. Oncogene. 2003;22(37):5813–5827. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bae JH, Kim JG, Heo K, Yang K, Kim TO, Yi JM. Identification of radiation-induced aberrant hypomethylation in colon cancer. BMC Genomics. 2015;16:56. doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-1229-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]