Abstract

Oral cancer is a serious and fatal disease. Cisplatin is the first line of chemotherapeutic agent for oral cancer therapy. However, the development of drug resistance and severe side effects cause tremendous problems clinically. In this study, we investigated the pharmacologic mechanisms of YC-1 on cisplatin-resistant human oral cancer cell line, CAR. Our results indicated that YC-1 induced a concentration-dependent and time-dependent decrease in viability of CAR cells analyzed by MTT assay. Real-time image analysis of CAR cells by IncuCyte™ Kinetic Live Cell Imaging System demonstrated that YC-1 inhibited cell proliferation and reduced cell confluence in a time-dependent manner. Results from flow cytometric analysis revealed that YC-1 promoted G0/G1 phase arrest and provoked apoptosis in CAR cells. The effects of cell cycle arrest by YC-1 were further supported by up-regulation of p21 and down-regulation of cyclin A, D, E and CDK2 protein levels. TUNEL staining showed that YC-1 caused DNA fragmentation, a late stage feature of apoptosis. In addition, YC-1 increased the activities of caspase-9 and caspase-3, disrupted the mitochondrial membrane potential (AYm) and stimulated ROS production in CAR cells. The protein levels of cytochrome c, Bax and Bak were elevated while Bcl-2 protein expression was attenuated in YC-1-treated CAR cells. In summary, YC-1 suppressed the viability of cisplatin-resistant CAR cells through inhibiting cell proliferation, arresting cell cycle at G0/G1 phase and triggering mitochondria-mediated apoptosis. Our results provide evidences to support the potentially therapeutic application of YC-1 on fighting against drug resistant oral cancer in the future.

Keywords: YC-1, G0/G1 phase arrest, mitochondria, Apoptosis, CAR cells

1. Introduction

According to the 2014 annual report of the Ministry of Health and Welfare, R.O.C. (Taiwan), cancer is the first leading cause of death among the ten leading chronic diseases in Taiwan. The number of cancer death reports was 46, 829 (28, 776 in men and 18, 053 in women), accounting for 28.6% of the total number of deaths. The death rate was 199.6 per 100, 000 population, increased by 1.3% from 2013 to 2014 [1, 2]. Oral cancer is the fifth leading cause of cancer death in Taiwan. The death rate of oral cancer was 11.4 per 100, 000 population [1, 2]. In Taiwan, the major risk factors of oral cancer are betel nut chewing [3–6], smoking [7], alcohol consumption [4, 8], inflammation [9, 10] and human papilloma virus (HPV) infection [11, 12]. The 5-year survival rate of oral cancer is 50% [13, 14]. Surgery, radiotherapy and chemotherapeutic drugs are the major treatments for oral cancer. The first-line chemotherapeutic drugs to treat oral cancer are cisplatin, carboplatin, 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), paclitaxel (Taxol®) and docetaxel (Taxotere®) [15–17]. However, surgery, radiotherapy and chemotherapy did not significantly improve the overall survival rate of oral cancer patients. On top of that, the development of drug resistance in the duration of chemotherapy remains as a clinical obstacle [18, 19]. To meet the need, designing novel compounds as well as discovering new targeting molecules that can overcome the resistance to chemotherapeutic drugs in oral cancer are clinically important.

YC-1 [3-(5’-hydroxymethyl-2’-furyl)-1-benzylindazole] was first designed and synthesized in our team [20, 21]. Current studies have shown that YC-1 has a wide spectrum of pharmacological activities, including anti-platelet [22–24], anti-inflammatory [25–29], anti-angiogenesis [30], neuro-protective [31–33], anti-hepatic fibrosis [34] and anti-cancer properties [20, 33, 35–56]. The underlying mechanism exerted by YC-1 included activation of NO-independent soluble guanylyl cyclase (sGC), inactivation of phosphodiesterase type 5 (PED5) [29, 57, 58] and inhibition of hypoxia-inducible factor 1a (HIF-1a) activity [22, 59, 60]. As for the anti-cancer activity, YC-1 can repress the proliferation of various types of cancer cells, including head and neck squamous cell carcinoma [48], esophageal squamous carcinoma [43], lung cancer [61–65], lymphoma [66, 67], bladder cancer [41, 68], hepatocellular carcinoma [52, 69], breast cancer [35, 55, 70], neuroblastoma [32], ovarian carcinoma [71], prostate cancer [72], pancreatic cancer [73], renal carcinoma [56, 74, 75], osteosarcoma [45], colon cancer [76, 77] and leukemia [20, 39, 49, 78]. In terms of the molecular mechanisms in anti-cancer activity, YC-1 induced cell cycle arrest at G0/G1 phase [50, 79, 80] or at S phase [52, 81], inhibited multidrug-resistant protein (MDR1) [82], reduced autophagy [83] and triggered apoptotic cell death [52]. In addition, YC-1 enhanced chemotherapeutic cisplatin sensitivity in hepatocellular carcinoma cells [84] and head and neck squamous cell carcinoma cells [48]. However, studies on whether YC-1 can inhibit cisplatin-resistant human oral cancer are scarce. The objective of this study was to investigate the anti-cancer effects of YC-1 on cisplatin-resistant human tongue squamous cell carcinoma CAR cells and its underlying mechanisms.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Chemicals and reagents

Cisplatin, propidium iodide (PI) and thiazolyl blue tetrazolium bromide (MTT) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Trypsin-EDTA was purchased from BioConcept (Allschwil/BL, Switzerland). Fetal bovine serum (FBS), L-glutamine, penicillin G, 2’, 7’-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (H2DCFDA) and 3, 3-dihexyloxa-carbocyanine iodide [DiOC6(3)] were obtained from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Carlsbad, CA, USA). Caspase-3 and caspase-9 activity assay kits were purchased from R&D Systems Inc. (Minneapolis, MN, USA). The primary antibodies against Bcl-2, Bax, cytochrome c, Apaf-1, AIF, p21, cyclin A, cyclin D, cyclin E, CDK 2, β-actin and the goat anti-rabbit or anti-mouse IgG-horseradish peroxidase (HRP) secondary antibodies were purchased from GeneTex, (Hsinchu, Taiwan). Pan-caspase inhibitor (z-VAD-fmk) and enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) detection kit (Immobilon Western Chemiluminescent HRP Substrate) were purchased from Merck Millipore (Billerica, MA, USA). YC-1 was designed and synthesized as detailed in the previous study [21].

2.2. Cell culture

The cisplatin-resistant cell line (CAR) was developed by treating CAL 27 cell line, a parental human tongue squamous cell carcinoma (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA, USA) with 10-80 μM of cisplatin. CAR cells are characterized by its stable resistance to cisplatin as previously described [1, 18, 85, 86]. The cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) fortified with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and 2 mM L-glutamine (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and were incubated at 37 °C with a humidified 5% CO2 air. The cisplatin-resistant CAR cells were constantly cultured in medium containing 80 μM cisplatin unless otherwise indicated [1, 18, 85, 86].

2.3. Cell viability assay

CAR cells (1 × 104 cells/per well) were seeded in 96-well plates in 100 μl medium with or without 25, 50, 75 and 100 μM of YC-1 for 24 h. After YC-1 treatment, DMEM containing 500 μg/ml of MTT was added and incubated at 37 °C for 4 h. The medium was then removed, and 100 μl DMSO was added to each well to dissolve the formed blue formazan crystals, followed by measuring the 570 nm absorbance of each well by the ELISA plate reader with a reference wavelength of 620 nm. For the caspase inhibition experiment, cells were pretreated with 15 μM z-VAD-fmk (a pan-caspase inhibitor) for 1 h before subjected to YC-1 administration. Cell morphological examination was observed and photographed by the IncuCyte™ Kinetic Live Cell Imaging System (Essen BioScience, Ann Arbor, MI, USA) [87–89].

2.4. IncuCyte cell proliferation and confluence assay

To measure the cell confluence, a stable mixture of CAR cells (2 × 104 cells) were plated into a 96-well plate. The cells were then incubated with or without 25, 50, 75 and 100 μM of YC-1. Cell confluence relative to the control cells was determined by the IncuCyte™ Kinetic Live Cell Imaging System (Essen BioScience) at a 2-h interval and up to 48 h [90].

2.5. Flow cytometry analysis of cell cycle distribution

CAR cells (2 × 105 cells/per well) were plated into the 12-well plates and then treated with 100 μM of YC-1 for 0, 12, 24, 36 and 48 h. The cells were then fixed, followed by staining with propidium iodide (PI) solution as previously described [91, 92]. The cell cycle profiling and the data analysis were determined utilizing a Muse Cell Analyzer (Merck Millipore, Hayward, CA, USA) [93–98].

2.6. Immunoblotting analysis

CAR cells (1 × 107/75-T flask) were treated with 0, 25, 50, 75 and 100 μM of YC-1 for 48 h. The cells were then harvested, and the total proteins in cell lysate were collected by SDS sample buffer. Briefly, protein sample from each treatment was subjected to electrophoresis on a 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel (SDS-PAGE), followed by electro-transferring to a PVDF membrane. The transferred membranes were blocked in 20 mM Tris-buffered saline/0.05% Tween-20 solution containing 5% non-fat dry milk for 1 h at room temperature. The membrane was then probed with the primary antibodies against proteins associated with either cell cycle regulation or apoptosis at 4 °C overnight. Afterwards, the membranes were washed with Tris-buffered saline/Tween-20 and incubated with secondary antibodies conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP). The blots were developed by an enhanced chemiluminescence kit (Immobilon Western HRP Substrate; Merck Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA), followed by X-ray film exposure [99, 100].

2.7. TUNEL staining

CAR cells (2 × 105 cells/ per well) were seeded into 12-well plates and incubated with 0, 25, 50, 75 and 100 of YC-1 for 48 h. At the end of the treatment, apoptotic DNA fragmentation was detected using the In Situ Cell Death Detection kit, Fluorescein (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Roche Applied Science, Mannheim, Germany) according to the protocol by the manufacturer [101–104].

2.8. Assays for caspase-3 and caspase-9 activities

CAR cells (2 × 105 cells/ per well) were seeded into 6-well plates and incubated with 0, 25, 50, 75 and 100 of YC-1 for 48 h. At the end of the treatment, cells were harvested and cell lysates were assessed in accordance with the manufacturer’s instruction provided in the caspase-3 and caspase-9 Colorimetric Assay kits (R&D Systems Inc.). Cell lysate protein was then incubated for 1 h at 37 °C with specific caspase-3 substrate (DEVD-pNA) or caspase-9 substrate (LEHD-pNA) in the reaction buffer (provided in the kits). The OD405 of the released pNA in each sample was measured as previously described [86, 105].

2.9. Detection of ROS generation and mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm)

CAR cells (2 × 105 cells/ per well) were seeded into 6-well plates and incubated with 0, 25, 50, 75 and 100 of YC-1 for 48 h. At the end of the treatment, cells were harvested and incubated with 10 μM H2DCFDA and 4 nM DiOC6 at 37 °C for 30 min for H2O2 detection and A¥m, respectively. The mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) was quantified by BD CellQuest Pro software (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) after analysis by flow cytometry [86, 105, 106].

2.10. Statistical analysis

All the statistical results are presented as the mean ± sd for at least three separate experiments. Statistical analysis of data was done using one-way ANOVA followed by Student’s t-test. ***P < 0.001 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. YC-1 decreased the viability and suppressed confluence of CAR cells

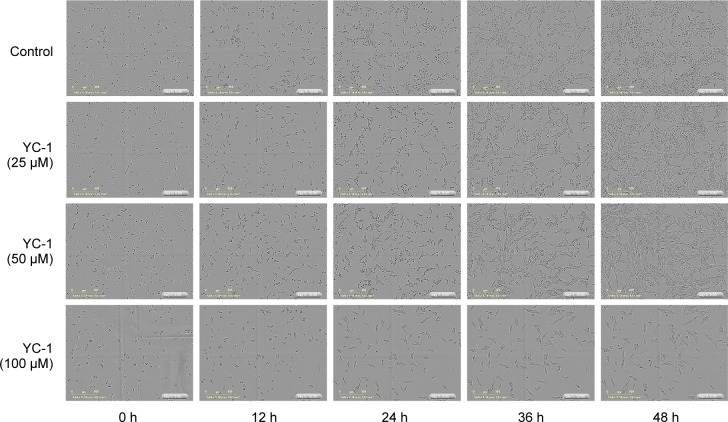

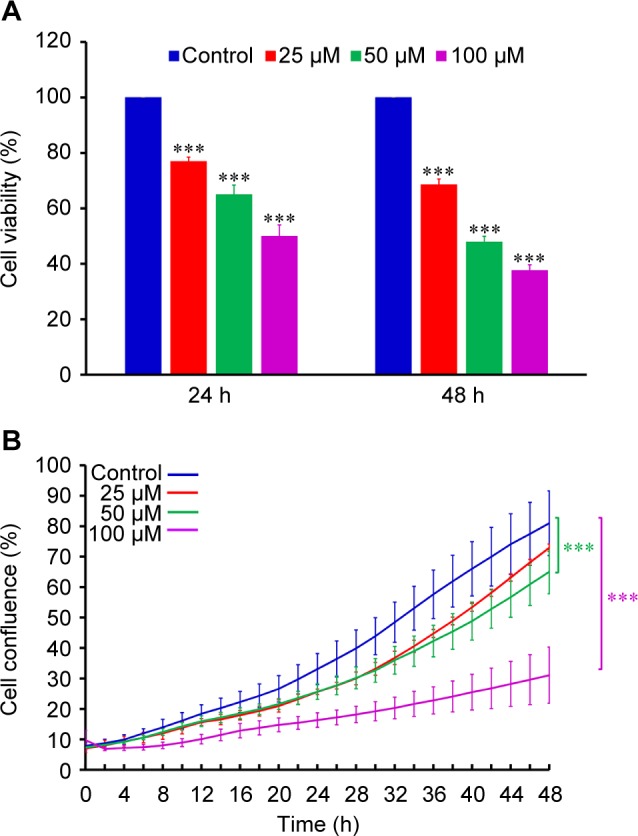

The cisplatin-resistant human oral CAR cells were treated with YC-1 (0, 25, 50 and 100 μM) for either 24 h or 48 h. The MTT assay demonstrated that YC-1 significantly decreased the cell viability in a concentration and time-dependent manner (Fig. 1A). The percentage of cell confluence relative to the control cells was determined by the IncuCyte™ Kinetic Live Cell Imaging System at a 2-h interval and up to 48 h. The administration of YC-1 (0, 25, 50 and 100 μM) inhibited the confluences of cultured CAR cells (Fig. 1B). The inhibition of cell confluence showed concentration and time-dependent. Images of cultured CAR cells under different YC-1 concentrations (0, 25, 50 and 100 μM) taken by IncuCyte™ Kinetic Live Cell Imaging System at the indicated period of time showed that YC-1 induced cell morphology changes and triggered cell death (Fig. 2). Herein, we also provide the realtime cell imaging of cultured CAR cells with or without YC-1 (100 μM) by IncuCyte™ Kinetic Live Cell Imaging System video (Supplementary video). Our data revealed that YC-1 exhibited cytotoxicity to CAR cells.

Fig. 1.

Effects of YC-1 on cell viability and cell confluence in CAR cells. Cells were incubated with 0, 25, 50 and 100 μM of YC-1 for various duration. (A) The cell viability was determined by MTT assay. (B) The cell confluence was determined by the IncuCyte™ Kinetic Live Cell Imaging System. Data are presented as the mean ± sd (n = 3). ***p < 0.001 versus untreated control.

Fig. 2.

Effects of YC-1 on cell morphology and confluence of CAR cells. Cells were incubated with 0, 25, 50 and 100 of YC-1 for 0, 12, 24, 36 and 48 h. The cell morphology and density was determined by the IncuCyte™ Kinetic Live Cell Imaging System.

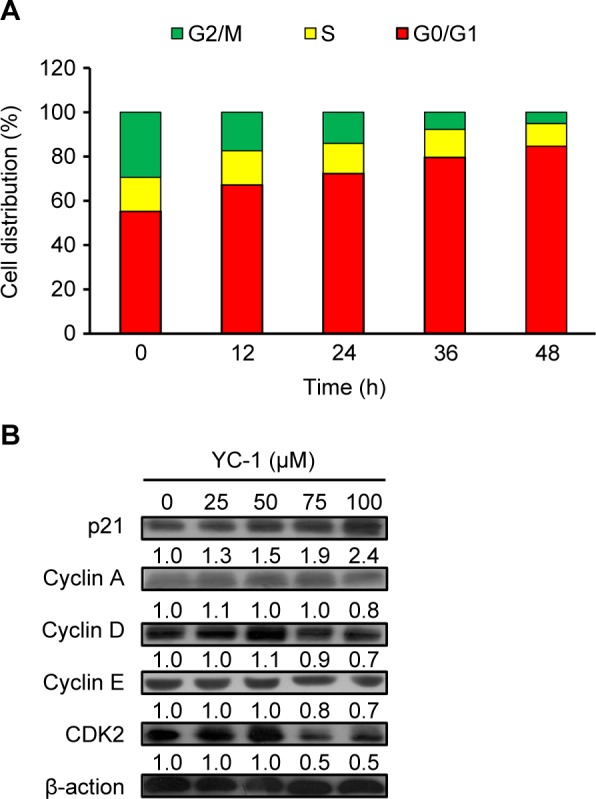

3.2. YC-1 caused G0/Gt cell cycle arrest and affected the expression levels of G0/G1 proteins of CAR cells

To verify whether YC-1 treatment affects the cell cycle distribution, CAR cells were administered with 100 μM of YC-1 for 0, 12, 24, 36 and 48 h. The percentage of cells in G0/G1, S and G2/ M phase were analyzed by DNA content stained with PI and flow cytometry. Our data indicated that YC-1 treatment resulted in cell cycle arrest at G0/Gj phase. The percentage of cells arrested at G0/Gj increased as the treatment duration lengthened. In the meanwhile, a marked decrease of the cells at G2/M phase was observed (Fig. 3A). The expression levels of proteins associated with G0/Gj were analyzed after 24-h treatment. YC-1 induced the protein expression of p21 in a concentration-dependent manner, while the protein expression of cyclins A, D, E and CDK2 was inhibited (Fig. 3B). These results indicated that YC-1 regulated CDK2 activation and caused G0/G1 phase arrest in the CAR cells.

Fig. 3.

Effects of YC-1 on cell cycle distribution and the levels of G0/G1 proteins of CAR cells. (A) Cells were incubated with 100 μM of YC-1 for 0, 12, 24, 36 and 48 h. The cell cycle distribution was assessed by PI staining and flow cytometric analysis. (B) Whole-cell lysates were prepared, and the levels of G0/G1 proteins were analyzed by western blot analysis.

3.3. YC-1 induced DNA fragmentation and enhanced cas- pase-9 and caspase-3 activities in CAR cells.

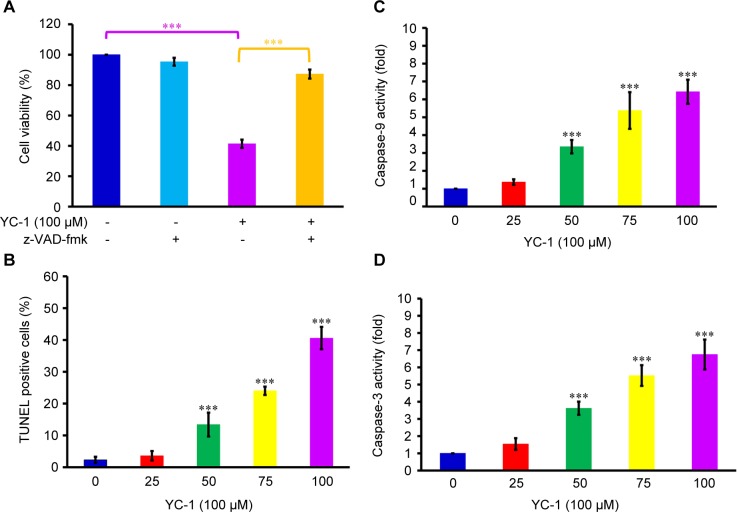

We examined whether YC-1 induces apoptosis in CAR cells. A significant reduction in cell viability from MTT assay was observed after cells were exposed to 100 μM of YC-1 for 48 h. However, the decreased cell viability induced by YC-1 was reversed by z-VAD-fmk (a pan-caspase inhibitor) (Fig. 4A). Results from TUNEL staining also showed that as the YC-1 concentration increased, more TUNEL positive cells were observed, indicating that more cells exhibited DNA fragmentation (Fig. 4B). To further investigate whether the cell death provoked by YC-1 was mediated through caspases activation, protein samples collected from CAR cells after YC-1 exposure for 48 h were analyzed. Treatment of YC-1 (0, 25, 50, 75 and 100 μM) significantly and concentration-dependently stimulated the activities of both caspases-9 and caspase-3 (Fig. 4C and 4D). Our data demonstrated that YC-1 induced apoptosis, and the activation of caspases was involved in apoptotic cell death in CAR cells.

Fig. 4.

Effects of YC-1 on DNA fragmentation, caspase-9 and caspase-3 activities in CAR cells. (A) Cells were incubated with 100 μM of YC-1 with or without z-VAD-fmk for 48 h. The cell viability was determined by MTT assay. (B) TUNEL assay, (C) caspase-9 and (D) caspase-3 activities were analyzed in CAR cells treated with 0, 25, 50, 75 and 100 μM of YC-1 for 48 h. Data are presented as the mean ± sd (n = 3). ***P < 0.001 versus untreated control.

3.4. YC-1 stimulated ROS production, collapsed mitochondrial membrane potential (AΨm) and altered the levels of apoptosis-related proteins in CAR cells

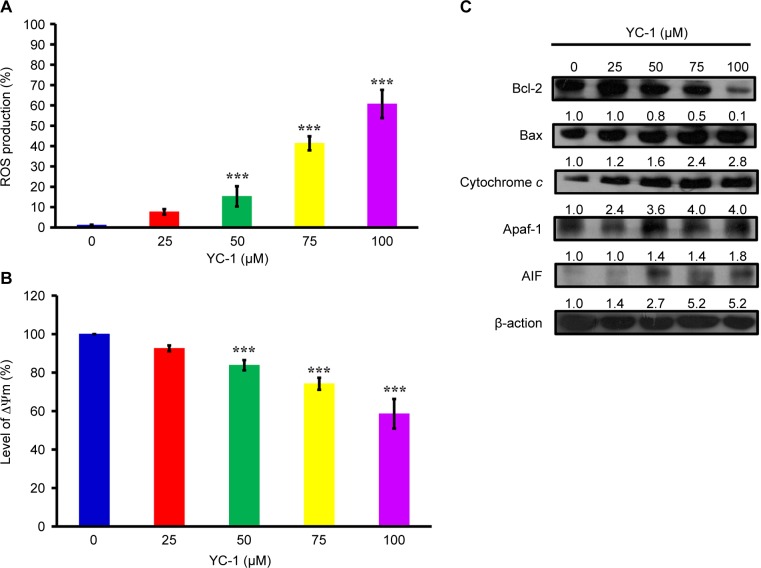

We investigated whether YC-1 stimulates ROS production. The production of ROS markedly elevated after cells were administrated with of YC-1 (0, 25, 50, 75 and 100 μM), and the elevation showed concentration-dependent (Fig. 5A). To confirm whether the mitochondrial pathway mediating YC-1-induced cell apoptosis, the level of ΔΨm was measured, and immunoblotting analysis was performed to evaluate the expression levels of proteins associated with mitochondria-dependent apoptotic pathways. CAR cells exhibited a decrease of AYm in a concentration-dependent manner after 48 h of YC-1 treatment (Fig. 5B). YC-1 suppressed the level of Bcl-2, while it promoted the protein expressions of Bax, cytochrome c, Apaqf-1 and AIF (Fig. 5C), indicating the involvement of mitochondria-dependent pathway.

Fig. 5.

Effects of YC-1 on ROS, mitochondrial membrane potential (∆Ψm) and the levels of apoptosis-related proteins in CAR cells. Cells were incubated with 0, 25, 50, 75 and 100 of YC-1 for 48 h. (A) ROS level was assessed by staining with H2DCFDA, and (B) loss of A¥m was measured with DiOC6(3) by flow cytometry. Data are presented as the mean ± sd (n = 3). ***P < 0.001 versus untreated control. (C) Whole-cell lysates were prepared, and the levels of apoptosis related proteins were analyzed by western blot analysis Data is presented.

4. Discussion

Discovering and exploring novel therapeutic strategy and underlying molecular mechanisms has been a major research focus in oral cancer therapy [107–110]. Studies on various cancer cells demonstrated that YC-1 possessed significant anti-cancer activities through several pathways. YC-1 can induce cell cycle arrest [81, 111, 112], apoptosis [81, 111, 112] and autophagy [83, 113, 114]. It also blocked angiogenesis [30, 115–117], cell migration [41, 43, 72, 118], metastasis [36, 64, 119] and reduce matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) activity [41, 72, 117]. Furthermore, YC-1 enhanced the chemo-sensitivity of cancer cells to cisplatin by regulating expression and activity of apoptosis-related proteins, leading to the activation of caspase-9 and caspase-3 signaling [120]. Recently, Tuttle et al. [48] reported that YC-1 inhibited cell proliferation, induced apoptotic cell death, and increased sensitivity to cisplatin in UM-1- and CAL 27-cisplatin resistance cells. However, the molecular mechanisms of YC-1-induced cell cycle arrest and death in cisplatin resistant oral cancer cells are not yet fully understood. In this study, our results showed that 25-100 of YC-1 significantly inhibited the proliferation of cisplatin-resistant CAR cells (Fig. 1, Fig. 2 and Supplementary video). YC-1 treatment increased the number of cells in the G0/ G1 phase, suggesting that YC-1 caused growth inhibition by promoting G0/G1 phase arrest in CAR cells (Fig. 3). The significant DNA fragmentation and caspase-3/ -9 activation in YC-1 treated cells (Fig. 4B, C, and D) indicate that YC-1 can induce caspase- dependent apoptosis in CAR cells. Our findings provide new insights addressing the anti-cancer activity of YC-1 in cisplatin-resistant CAR cells at the molecular levels.

Once the mitochondrial apoptotic signaling is provoked, changes in the mitochondrial membrane permeability would lead to the loss of mitochondrial membrane potential. In addition, the mitochondrial outer membrane becomes leaky and releases the proapoptotic proteins; including cytochrome c, Apaf-1, procas- pase-9, AIF and Endo G into cytosol. These proteins can then activate caspase-9 and caspase-3 and result in DNA fragmentation, a unique feature of the late stage apoptosis [121–125]. Bcl-2 family proteins are also involved in the regulation of apoptosis through modulating mitochondrial functions [121, 124]. Our results showed that YC-1 induced apoptosis, as evidenced by the reduced viability and the significant number of TUNEL-positive cells (Fig 4A, B). YC-1 induced apoptosis was further confirmed by pan-caspase inhibitor which reversed the reduction of cellular viability in YC-1 treated cells (Fig 4A). In addition, the loss of ΔΨm, elevation of ROS production, and the changes in quantity of mitochondria-related proteins (Bcl-2, Bax, cytochrome c, Apaf-1 and AIF) were observed after YC-1 treatment (Fig. 5). These results suggested that YC-1-induced apoptosis was mediated through the activation of caspase cascades, and this apoptotic death was mitochondria-dependent. This study is the first report to prove the involvement of a mitochondrial pathway in YC-1-induced apoptosis in cisplatin-resistant CAR cells.

It has been documented that YC-1 inhibited cell proliferation and cell cycle progression from G0/G1 to S phase in rat mesangial cell and human hepatocellular carcinoma cells [50, 80]. Teng et al. [50] demonstrated that YC-1 inhibited human hepatocellular carcinoma cell proliferation through G0/G1 phase arrest and increased p21 and p27 protein levels. However, Yeo. et al. reported YC-1 induced S phase arrest and apoptosis in Hep3B cells [81]. Our results (Fig 3) were consistent with those of Teng el al. [50] and suggested that, by down-regulation of CDK2/cyclin A, D, and E activities, YC-1 blocked cell cycle at G0/G1 phase.

The IncuCyte™ Kinetic Live Cell Imaging System provides a continuous time-lapsed recording and quantitation of cell life images, which facilitates a robust data collection and analysis. This system can be used to detect cell activities such as cell proliferation, migration, invasion, wound healing, caspase activity and autophagy [126-128]. In the present study, we are the first group using this imaging system to characterize cell proliferation and confluence in YC-1-treated CAR cells (Fig. 2 and Supplementary video). Thus, more studies on anti-cancer activity of YC-1 can be accelerated and examined by this cell image system in the near future.

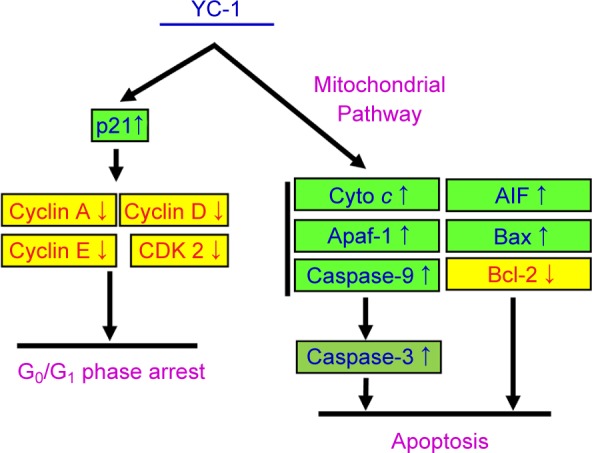

5. Conclusions

Fig. 6 illustrated the proposed molecular mechanism of YC-1-provoked G0/G1 phase arrest and apoptosis in CAR cells. Our results revealed that YC-1 arrested at G0/Gj phase through regulating p21, cyclin A, D, E and CDK2 activity. In addition, YC-1 induced apoptosis in CAR cells via caspases activation and mitochondria-dependent pathway. YC-1 is proved to be potential adjuvants or alternatives to cisplatin treatment in cisplatin-resistant oral cancer.

Fig. 6.

Schematic diagram of proposed molecular mechanism of YC-1-induced G0/G1 phase arrest and apoptosis in cisplatin- resistant human oral cancer CAR cells.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Supplementary video

Effects of YC-1 on cell confluence in CAR cells. cclls were incubatcd with or without 100 μM of YC-1. The dyuamic ccll imaging was 3en by the IneuC’yte™ Kinetic Live Cell Imaging System at a 2 h interval and up to 48 h

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the grant from China Medical University Hospital, Taichung, Taiwan (DMR-106-122). The authors also would like to express our gratitude to Mr. Meng-Jou Liao (Tekon Scientific Corp.), Mr. Chin-Chen Lin (Tekon Scientific Corp.) and Mr. Chang-Wei Li (AllBio Science Incorporated, Taiwan) for their excellent technique and equipment supports.

References

- 1. Yuan CH, Horng CT, Lee CF, Chiang NN, Tsai FJ, Lu CC, et al. Epigallocatechin gallate sensitizes cisplatin-resistant oral cancer CAR cell apoptosis and autophagy through stimulating AKT/ STAT3 pathway and suppressing multidrug resistance 1 signaling. Environ Toxicol. 2017; 32: 845–855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chuang SL, Su WW, Chen SL, Yen AM, Wang CP, Fann JC, et al. Population-based screening program for reducing oral cancer mortality in 2, 334, 299 Taiwanese cigarette smokers and/or betel quid chewers. Cancer. 2017; 123: 1597–1609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tsai KY, Su CC, Chiang CT, Tseng YT, Lian IB. Environmental heavy metal as a potential risk factor for the progression of oral potentially malignant disorders in central Taiwan. Cancer Epidemiol. 2017; 47: 118–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chou CH, Chou YE, Chuang CY, Yang SF, Lin CW. Combined effect of genetic polymorphisms of AURKA and environmental factors on oral cancer development in Taiwan. PLoS One. 2017; 12: e0171583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chan CY, Lien CH, Lee MF, Huang CY. Quercetin suppresses cellular migration and invasion in human head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC). Biomedicine (Taipei). 2016; 6: 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Huang YP, Chang NW. PPARalpha modulates gene expression profiles of mitochondrial energy metabolism in oral tumorigenesis. Biomedicine (Taipei). 2016; 6: 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Butler C, Lee YA, Li S, Li Q, Chen CJ, Hsu WL, et al. Diet and the risk of head-and-neck cancer among never-smokers and smokers in a Chinese population. Cancer Epidemiol. 2017; 46: 20–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wang WH, Hsuan KY, Chu LY, Lee CY, Tyan YC, Chen ZS, et al. Anticancer Effects of Salvia miltiorrhiza Alcohol Extract on Oral Squamous Carcinoma Cells. vid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2017; 2017: 5364010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lien MY, Lin CW, Tsai HC, Chen YT, Tsai MH, Hua CH, et al. Impact of CCL4 gene polymorphisms and environmental factors on oral cancer development and clinical characteristics. Oncotarget. 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tien AJ, Chien CY, Chen YH, Lin LC, Chien CT. Fruiting Bodies of Antrodia cinnamomea and Its Active Triterpenoid, Antcin K, Ameliorates N-Nitrosodiethylamine-Induced Hepatic Inflammation, Fibrosis and Carcinogenesis in Rats. Am J Chin Med. 2017; 45: 173–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ragin C, Liu JC, Jones G, Shoyele O Sowunmi B Kennett R, et al. Prevalence of HPV Infection in Racial-Ethnic Subgroups of Head and Neck Cancer Patients. Carcinogenesis. 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Huang SF, Li HF, Liao CT, Wang HM, Chen IH, Chang JT, et al. Association of HPV infections with second primary tumors in early-staged oral cavity cancer. Oral Dis. 2012; 18: 809–815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Suzuki R, Matsushima Y, Okudaira N, Sakagami H, Shirataki Y. Cytotoxic Components Against Human Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma Isolated from Andrographis paniculata. Anticancer Res. 2016; 36: 5931–5935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kumar M, Nanavati R, Modi TG, Dobariya C. Oral cancer: Etiology and risk factors: A review. J Cancer Res Ther. 2016; 12: 45863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Schmaltz H, Borel C, Ciftci S, Takeda-Raguin C, Debry C, Schultz P, et al. Induction chemotherapy before surgery for unresectable head and neck cancer. B-ENT. 2016; 12: 29–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Noronha V, Patil V, Joshi A, Muddu V, Bhattacharjee A, Juvekar S, et al. Is taxane/platinum/5 fluorouracil superior to taxane/platinum alone and does docetaxel trump paclitaxel in induction therapy for locally advanced oral cavity cancers?. Indian J Cancer. 2015; 52: 70–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chung CH, Rudek MA, Kang H, Marur S, John P, Tsottles N, et al. A phase I study afatinib/carboplatin/paclitaxel induction chemotherapy followed by standard chemoradiation in HPV-negative or high-risk HPV-positive locally advanced stage III/IVa/IVb head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Oncol. 2016; 53: 54–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chang CH, Lee CY, Lu CC, Tsai FJ, Hsu YM, Tsao JW, et al. Resveratrol-induced autophagy and apoptosis in cisplatin-resistant human oral cancer CAR cells: A key role of AMPK and Akt/mTOR signaling. Int J Oncol. 2017; 50: 873–882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ding L, Ren J, Zhang D, Li Y, Huang X, Ji J, et al. The TLR3 Agonist Inhibit Drug efflux and Sequentially Consolidates Low-dose Cisplatin-based Chemoimmunotherapy while Reducing Side effects. Mol Cancer Ther. 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chung JG, Yang JS, Huang LJ, Lee FY, Teng CM, Tsai SC, et al. Proteomic approach to studying the cytotoxicity of YC-1 on U937 leukemia cells and antileukemia activity in orthotopic model of leukemia mice. Proteomics. 2007; 7: 3305–3317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lee FY, Lien JC, Huang LJ, Huang TM, Tsai SC, Teng CM, et al. Synthesis of 1-benzyl-3-(5’-hydroxymethyl-2’-furyl)indazole analogues as novel antiplatelet agents. J Med Chem. 2001; 44: 3746–3749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chun YS, Yeo EJ, Park JW. Versatile pharmacological actions of YC-1: anti-platelet to anticancer. Cancer Lett. 2004; 207: 1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Nakane M. Soluble guanylyl cyclase: physiological role as an NO receptor and the potential molecular target for therapeutic application. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2003; 41: 865–870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tulis DA, Bohl Masters KS, Lipke EA, Schiesser RL, Evans AJ, Peyton KJ, et al. YC-1-mediated vascular protection through inhibition of smooth muscle cell proliferation and platelet function. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002; 291: 1014–1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Yun S, Lee SH, Kang YH, Jeong M, Kim MJ, Kim MS, et al. YC-1 enhances natural killer cell differentiation from hematopoietic stem cells. Int Immunopharmacol. 2010; 10: 481–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lu DY, Tang CH, Liou HC, Teng CM, Jeng KC, Kuo SC, et al. YC-1 attenuates LPS-induced proinflammatory responses and activation of nuclear factor-kappaB in microglia. Br J Pharmacol. 2007; 151: 396–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hwang TL, Hung HW, Kao SH, Teng CM, Wu CC, Cheng SJ. Soluble guanylyl cyclase activator YC-1 inhibits human neutrophil functions through a cGMP-independent but cAMP-dependent pathway. Mol Pharmacol. 2003; 64: 1419–1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wu SN. Large-conductance Ca2 + -activated K + channels: physiological role and pharmacology. Curr Med Chem. 2003; 10: 64961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ko FN, Wu CC, Kuo SC, Lee FY, Teng CM. YC-1, a novel activator of platelet guanylate cyclase. Blood. 1994; 84: 4226–4233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wang J, Li G, Wang Y, Tang S, Sun X, Feng X, et al. Suppression of tumor angiogenesis by metformin treatment via a mechanism linked to targeting of HER2/HIF-1alpha/VEGF secretion axis. Oncotarget. 2015; 6: 44579–44592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Na JI, Na JY, Choi WY, Lee MC, Park MS, Choi KH, et al. The HIF-1 inhibitor YC-1 decreases reactive astrocyte formation in a rodent ischemia model. Am J Transl Res. 2015; 7: 751–760. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Chio CC, Lin JW, Cheng HA, Chiu WT, Wang YH, Wang JJ, et al. MicroRNA-210 targets antiapoptotic Bcl-2 expression and mediates hypoxia-induced apoptosis of neuroblastoma cells. Arch Toxicol. 2013; 87: 459–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Chou CW, Wang CC, Wu CP, Lin YJ, Lee YC, Cheng YW, et al. Tumor cycling hypoxia induces chemoresistance in glioblastoma multiforme by upregulating the expression and function of ABCB1. Neuro Oncol. 2012; 14: 1227–1238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Xiao J, Jin C, Liu Z, Guo S, Zhang X, Zhou X, et al. The design, synthesis, and biological evaluation of novel YC-1 derivatives as potent anti-hepatic fibrosis agents. Org Biomol Chem. 2015; 13: 7257–7264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Carroll CE, Liang Y, Benakanakere I, Besch-Williford C, Hyder SM. The anticancer agent YC-1 suppresses progestin-stimulated VEGF in breast cancer cells and arrests breast tumor development. Int J Oncol. 2013; 42: 179–187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Chen CJ, Hsu MH, Huang LJ, Yamori T, Chung JG, Lee FY, et al. Anticancer mechanisms of YC-1 in human lung cancer cell line, NCI-H226. Biochem Pharmacol. 2008; 75: 360–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lee JC, Chou LC, Lien JC, Wu JC, Huang CH, Chung CH, et al. CLC604 preferentially inhibits the growth of HER2-overexpressing cancer cells and sensitizes these cells to the inhibitory effect of Taxol in vitro and in vivo. Oncol Rep. 2013; 30: 1762–1772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lee SJ, Kim YJ, Lee CS, Bae J. Combined application of camptothecin and the guanylate cyclase activator YC-1: Impact on cell death and apoptosis-related proteins in ovarian carcinoma cell lines. Chem Biol Interact. 2009; 181: 185–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Flamigni F, Facchini A, Stanic I, Tantini B, Bonavita F, Stefanelli C. Control of survival of proliferating L1210 cells by soluble guany-late cyclase and p44/42 mitogen-activated protein kinase modulators. Biochem Pharmacol. 2001; 62: 319–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wang SX, Pei ZZ, Wu XH, Li JK, Yang YJ. Effect of YC-1 on HIF-1 alpha and VEGF expression in human hepatocarcinoma cell lines. Zhonghua Gan Zang Bing Za Zhi. 2009; 17: 308–309. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Li Y, Zhao X, Tang H, Zhong Z, Zhang L, Xu R, et al. Effects of YC-1 on hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha in hypoxic human bladder transitional carcinoma cell line T24 cells. Urol Int. 2012; 88: 95–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Zhao Q, Du J, Gu H, Teng X, Zhang Q, Qin H, et al. Effects of YC-1 on hypoxia-inducible factor 1-driven transcription activity, cell proliferative vitality, and apoptosis in hypoxic human pancreatic cancer cells. Pancreas. 2007; 34: 242–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Feng Y, Zhu H, Ling T, Hao B, Zhang G, Shi R. Effects of YC-1 targeting hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha in oesophageal squamous carcinoma cell line Eca109 cells. Cell Biol Int. 2011; 35: 491–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Lee CS, Kwak SW, Kim YJ, Lee SA, Park ES, Myung SC, et al. Guanylate cyclase activator YC-1 potentiates apoptotic effect of licochalcone A on human epithelial ovarian carcinoma cells via activation of death receptor and mitochondrial pathways. Eur J Pharmacol. 2012; 683: 54–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Liang D, Yang M, Guo B, Yang L, Cao J, Zhang X. HIF-1alpha induced by beta-elemene protects human osteosarcoma cells from undergoing apoptosis. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2012; 138: 186577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Chai ZT, Kong J, Zhu XD, Zhang YY, Lu L, Zhou JM, et al. MicroRNA-26a inhibits angiogenesis by down-regulating VEGFA through the PIK3C2alpha/Akt/HIF-1alpha pathway in hepatocellular carcinoma. PLoS One. 2013; 8: e77957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Hong B, Lui VW, Hui EP, Lu Y, Leung HS, Wong EY, et al. Reverse phase protein array identifies novel anti-invasion mechanisms of YC-1. Biochem Pharmacol. 2010; 79: 842–852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Tuttle TR, Takiar V, Kumar B, Kumar P, Ben-Jonathan N. Soluble guanylate cyclase stimulators increase sensitivity to cisplatin in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma cells. Cancer Lett. 2017; 389: 33–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Chou LC, Huang LJ, Yang JS, Lee FY, Teng CM, Kuo SC. Synthesis of furopyrazole analogs of 1-benzyl-3-(5-hydroxymethyl-2-furyl)indazole (YC-1) as novel anti-leukemia agents. Bioorg Med Chem. 2007; 15: 1732–1740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Wang SW, Pan SL, Guh JH, Chen HL, Huang DM, Chang YL, et al. YC-1 [3-(5’-Hydroxymethyl-2’-furyl)-1-benzyl Indazole] exhibits a novel antiproliferative effect and arrests the cell cycle in G0–G1 in human hepatocellular carcinoma cells. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005; 312: 917–925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Pan SL, Guh JH, Peng CY, Wang SW, Chang YL, Cheng FC, et al. YC-1 [3-(5’-hydroxymethyl-2’-furyl)-1-benzyl indazole] inhibits endothelial cell functions induced by angiogenic factors in vitro and angiogenesis in vivo models. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005; 314: 35–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Kong J, Kong F, Gao J, Zhang Q, Dong S, Gu F, et al. YC-1 enhances the anti-tumor activity of sorafenib through inhibition of signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) in hepatocellular carcinoma. Mol Cancer. 2014; 13: 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Cheng Y, Li W, Liu Y, Cheng HC, Ma J, Qiu L. YC-1 exerts inhibitory effects on MDA-MB-468 breast cancer cells by targeting EGFR in vitro and in vivo under normoxic condition. Chin J Cancer. 2012; 31: 248–256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Wu SY, Pan SL, Chen TH, Liao CH, Huang DY, Guh JH, et al. YC-1 induces apoptosis of human renal carcinoma A498 cells in vitro and in vivo through activation of the JNK pathway. Br J Pharmacol. 2008; 155: 505–513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Chang LC, Lin HY, Tsai MT, Chou RH, Lee FY, Teng CM, et al. YC-1 inhibits proliferation of breast cancer cells by down- regulating EZH2 expression via activation of c-Cbl and ERK. Br J Pharmacol. 2014; 171: 4010–4025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Yeo EJ, Chun YS, Cho YS, Kim J, Lee JC, Kim MS, et al. YC-1: a potential anticancer drug targeting hypoxia-inducible factor 1. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003; 95: 516–525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Mullershausen F, Russwurm M, Friebe A, Koesling D. Inhibition of phosphodiesterase type 5 by the activator of nitric oxide-sensitive guanylyl cyclase BAY 41–2272. Circulation. 2004; 109: 1711–1713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Wang H, Kohr MJ, Traynham CJ, Ziolo MT. Phosphodiesterase 5 restricts NOS3/Soluble guanylate cyclase signaling to L-type Ca2 + current in cardiac myocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2009; 47: 30414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Chu PW, Beart PM, Jones NM. Preconditioning protects against oxidative injury involving hypoxia-inducible factor-1 and vascular endothelial growth factor in cultured astrocytes. Eur J Pharmacol. 2010; 633: 24–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Yeo EJ, Chun YS, Park JW. New anticancer strategies targeting HIF-1. Biochem Pharmacol. 2004; 68: 1061–1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Ikezawa Y, Sakakibara-Konishi J, Mizugaki H, Oizumi S, Nishimura M. Inhibition of Notch and HIF enhances the antitumor effect of radiation in Notch expressing lung cancer. Int J Clin Oncol. 2017; 22: 59–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Wan J, Wu W, Huang Y, Ge W, Liu S. Incomplete radiofrequency ablation accelerates proliferation and angiogenesis of residual lung carcinomas via HSP70/HIF-1alpha. Oncol Rep. 2016; 36: 659–668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Zhao T, Zhu Y, Morinibu A, Kobayashi M, Shinomiya K, Itasaka S, et al. HIF-1-mediated metabolic reprogramming reduces ROS levels and facilitates the metastatic colonization of cancers in lungs. Sci Rep. 2014; 4: 3793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Nurwidya F, Takahashi F, Kobayashi I, Murakami A, Kato M, Minakata K, et al. Treatment with insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor inhibitor reverses hypoxia-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition in non-small cell lung cancer. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2014; 455: 332–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Hsia TC, Liu WH, Qiu WW, Luo J, Yin MC. Maslinic acid induces mitochondrial apoptosis and suppresses HIF-1alpha expression in A549 lung cancer cells under normoxic and hypoxic conditions. Molecules. 2014; 19: 19892–19906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Kambayashi S, Igase M, Kobayashi K, Kimura A, Shimokawa Miyama T, Baba K, et al. Hypoxia inducible factor 1alpha expression and effects of its inhibitors in canine lymphoma. J Vet Med Sci. 2015; 77: 1405–1412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Chen WL, Wang CC, Lin YJ, Wu CP, Hsieh CH. Cycling hypoxia induces chemoresistance through the activation of reactive oxygen species-mediated B-cell lymphoma extra-long pathway in glioblastoma multiforme. J Transl Med. 2015; 13: 389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Xue M, Li X, Li Z, Chen W. Urothelial carcinoma associated 1 is a hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha-targeted long noncoding RNA that enhances hypoxic bladder cancer cell proliferation, migration, and invasion. Tumour Biol. 2014; 35: 6901–6912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Ma W, Shi X, Lu S, Wu L, Wang Y. Hypoxia-induced overexpression of DEC1 is regulated by HIF-1alpha in hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncol Rep. 2013; 30: 2957–2962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Aguilar H, Urruticoechea A, Halonen P, Kiyotani K, Mushiroda T, Barril X, et al. VAV3 mediates resistance to breast cancer endocrine therapy. Breast Cancer Res. 2014; 16: R53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Lee CS, Kim YJ, Kim W, Myung SC. Guanylate cyclase activator YC-1 enhances TRAIL-induced apoptosis in human epithelial ovarian carcinoma cells via activation of apoptosis-related proteins. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2011; 109: 283–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Dai Y, Bae K, Siemann DW. Impact of hypoxia on the metastatic potential of human prostate cancer cells. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011; 81: 521–528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Wang L, Zhou W, Gou S, Wang T, Liu T, Wang C. Insulin promotes proliferative vitality and invasive capability of pancreatic cancer cells via hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha pathway. J Hua-zhong Univ Sci Technolog Med Sci. 2010; 30: 349–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Cho IR, Koh SS, Min HJ, Park EH, Ratakorn S, Jhun BH, et al. Down-regulation of HIF-1alpha by oncolytic reovirus infection independently of VHL and p53. Cancer Gene Ther. 2010; 17: 36572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Aubert S, Fauquette V, Hemon B, Lepoivre R, Briez N, Bernard D, et al. MUC1, a new hypoxia inducible factor target gene, is an actor in clear renal cell carcinoma tumor progression. Cancer Res. 2009; 69: 5707–5715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Deguchi A, Xing SW, Shureiqi I, Yang P, Newman RA, Lippman SM, et al. Activation of protein kinase G up-regulates expression of 15-lipoxygenase-1 in human colon cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2005; 65: 8442–8447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Liu L, Li H, Underwood T, Lloyd M, David M, Sperl G, et al. Cyclic GMP-dependent protein kinase activation and induction by exisulind and CP461 in colon tumor cells. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2001; 299: 583–592. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Wang F, Chen BA, Cheng J, Xu WL, Wang XM, Ding JH, et al. Effects of hypoxia-inducible factor inhibitor on expression of HIF- 1alpha and VEGF and induction of apoptosis in leukemic cell lines. Zhongguo Shi Yan Xue Ye Xue Za Zhi. 2010; 18: 74–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Hsu HK, Juan SH, Ho PY, Liang YC, Lin CH, Teng CM, et al. YC-1 inhibits proliferation of human vascular endothelial cells through a cyclic GMP-independent pathway. Biochem Pharmacol. 2003; 66: 263–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Chiang WC, Teng CM, Lin SL, Chen YM, Tsai TJ, Hsieh BS. YC-inhibited proliferation of rat mesangial cells through suppression of cyclin D1-independent of cGMP pathway and partially reversed by p38 MAPK inhibitor. Eur J Pharmacol. 2005; 517: 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Yeo EJ, Ryu JH, Chun YS, Cho YS, Jang IJ, Cho H, et al. YC-1 induces S cell cycle arrest and apoptosis by activating checkpoint kinases. Cancer Res. 2006; 66: 6345–6352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Hung CC, Liou HH. YC-1, a novel potential anticancer agent, inhibit multidrug-resistant protein via cGMP-dependent pathway. Invest New Drugs. 2011; 29: 1337–1346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Zhou Q, Liu H, Sun Q, Zhang L, Lin H, Yuan G, et al. Adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase/mammalian target of rapamycin-dependent autophagy protects human dental pulp cells against hypoxia. J Endod. 2013; 39: 768–773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Tung JN, Cheng YW, Hsu CH, Liu TZ, Hsieh PY, Ting LL, et al. Normoxically overexpressed hypoxia inducible factor 1-alpha is involved in arsenic trioxide resistance acquisition in hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011; 18: 1492–1500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Hsieh MT, Chen HP, Lu CC, Chiang JH, Wu TS, Kuo DH, et al. The novel pterostilbene derivative ANK-199 induces autophagic cell death through regulating PI3 kinase class III/beclin 1/Atgrelated proteins in cisplatinresistant CAR human oral cancer cells. Int J Oncol. 2014; 45: 782–794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Chang PY, Peng SF, Lee CY, Lu CC, Tsai SC, Shieh TM, et al. Curcumin-loaded nanoparticles induce apoptotic cell death through regulation of the function of MDR1 and reactive oxygen species in cisplatin-resistant CAR human oral cancer cells. Int J Oncol. 2013; 43: 1141–1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Yang JS, Chen GW, Hsia TC, Ho HC, Ho CC, Lin MW, et al. Di-allyl disulfide induces apoptosis in human colon cancer cell line (COLO 205) through the induction of reactive oxygen species, endoplasmic reticulum stress, caspases casade and mitochondrial-dependent pathways. Food Chem Toxicol. 2009; 47: 171–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Lai KC, Huang AC, Hsu SC, Kuo CL, Yang JS, Wu SH, et al. Benzyl isothiocyanate (BITC) inhibits migration and invasion of human colon cancer HT29 cells by inhibiting matrix metalloproteinase-2/-9 and urokinase plasminogen (uPA) through PKC and MAPK signaling pathway. J Agric Food Chem. 2010; 58: 2935–2942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Huang WW, Chiu YJ, Fan MJ, Lu HF, Yeh HF, Li KH, et al. Kaempferol induced apoptosis via endoplasmic reticulum stress and mitochondria-dependent pathway in human osteosarcoma U-2 OS cells. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2010; 54: 1585–1595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Chang WM, Lin YF, Su CY, Peng HY, Chang YC, Hsiao JR, et al. Parathyroid Hormone-Like Hormone is a Poor Prognosis Marker of Head and Neck Cancer and Promotes Cell Growth via RUNX2 Regulation. Sci Rep. 2017; 7: 41131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Chiu YJ, Hour MJ, Lu CC, Chung JG, Kuo SC, Huang WW, et al. Novel quinazoline HMJ-30 induces U-2 OS human osteogenic sarcoma cell apoptosis through induction of oxidative stress and up-regulation of ATM/p53 signaling pathway. J Orthop Res. 2011; 29: 1448–1456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Yang JS, Hour MJ, Kuo SC, Huang LJ, Lee MR. Selective induction of G2/M arrest and apoptosis in HL-60 by a potent anticancer agent, HMJ-38. Anticancer Res. 2004; 24: 1769–1778. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Lin CF, Yang JS, Lin C, Tsai FJ, Lu CC, Lee MR. CCY-1a–E2 induces G2/M phase arrest and apoptotic cell death in HL-60 leukemia cells through cyclin-dependent kinase 1 signaling and the mitochondria-dependent caspase pathway. Oncol Rep. 2016; 36: 1633–1639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Lai KC, Lu CC, Tang YJ, Chiang JH, Kuo DH, Chen FA, et al. Allyl isothiocyanate inhibits cell metastasis through suppression of the MAPK pathways in epidermal growth factorstimulated HT29 human colorectal adenocarcinoma cells. Oncol Rep. 2014; 31: 189–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Huang WW, Tsai SC, Peng SF, Lin MW, Chiang JH, Chiu YJ, et al. Kaempferol induces autophagy through AMPK and AKT signaling molecules and causes G2/M arrest via downregulation of CDK1/ cyclin B in SK-HEP-1 human hepatic cancer cells. Int J Oncol. 2013; 42: 2069–2077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Chen YF, Yang JS, Chang WS, Tsai SC, Peng SF, Zhou YR. Houttuynia cordata Thunb extract modulates G0/G1 arrest and Fas/CD95- mediated death receptor apoptotic cell death in human lung cancer A549 cells. J Biomed Sci. 2013; 20: 18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Liu CY, Yang JS, Huang SM, Chiang JH, Chen MH, Huang LJ, et al. Smh-3 induces G(2)/M arrest and apoptosis through calcium-mediated endoplasmic reticulum stress and mitochondrial signaling in human hepatocellular carcinoma Hep3B cells. Oncol Rep. 2013; 29: 751–762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Huang SH, Wu LW, Huang AC, Yu CC, Lien JC, Huang YP, et al. Benzyl isothiocyanate (BITC) induces G2/M phase arrest and apoptosis in human melanoma A375.S2 cells through reactive oxygen species (ROS) and both mitochondria-dependent and death receptor-mediated multiple signaling pathways. J Agric Food Chem. 2012; 60: 665–675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Ma CY, Ji WT, Chueh FS, Yang JS, Chen PY, Yu CC, et al. Butein inhibits the migration and invasion of SK-HEP-1 human hepatocar- cinoma cells through suppressing the ERK, JNK, p38, and uPA signaling multiple pathways. J Agric Food Chem. 2011; 59: 9032–9038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Chiang JH, Yang JS, Lu CC, Hour MJ, Chang SJ, Lee TH, et al. Newly synthesized quinazolinone HMJ-38 suppresses angiogeneticresponses and triggers human umbilical vein endothelial cell apoptosis through p53-modulated Fas/death receptor signaling. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2013; 269: 150–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Lu CC, Yang JS, Chiang JH, Hour MJ, Lin KL, Lee TH, et al. Cell death caused by quinazolinone HMJ-38 challenge in oral carcinoma CAL 27 cells: dissections of endoplasmic reticulum stress, mitochondrial dysfunction and tumor xenografts. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014; 1840: 2310–2320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Lin C, Tsai SC, Tseng MT, Peng SF, Kuo SC, Lin MW, et al. AKT serine/threonine protein kinase modulates baicalin-triggered autophagy in human bladder cancer T24 cells. Int J Oncol. 2013; 42: 993–1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Tsai SC, Yang JS, Peng SF, Lu CC, Chiang JH, Chung JG, et al. Bufalin increases sensitivity to AKT/mTOR-induced autophagic cell death in SK-HEP-1 human hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Int J Oncol. 2012; 41: 1431–1442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Lu CC, Yang JS, Chiang JH, Hour MJ, Lin KL, Lin JJ, et al. Novel quinazolinone MJ-29 triggers endoplasmic reticulum stress and intrinsic apoptosis in murine leukemia WEHI-3 cells and inhibits leukemic mice. PLoS One. 2012; 7: e36831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Peng SF, Lee CY, Hour MJ, Tsai SC, Kuo DH, Chen FA, et al. Curcumin-loaded nanoparticles enhance apoptotic cell death of U2OS human osteosarcoma cells through the Akt-Bad signaling pathway. Int J Oncol. 2014; 44: 238–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Tsai YF, Huang CW, Chiang JH, Tsai FJ, Hsu YM, Lu CC, et al. Gadolinium chloride elicits apoptosis in human osteosarcoma U-2 OS cells through extrinsic signaling, intrinsic pathway and endoplasmic reticulum stress. Oncol Rep. 2016; 36: 3421–3426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Mason JM, Wei X, Fletcher GC, Kiarash R, Brokx R, Hodgson R, et al. Functional characterization of CFI-402257, a potent and selective Mps1/TTK kinase inhibitor, for the treatment of cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017; 114: 3127–3132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Hour MJ, Lee KH, Chen TL, Lee KT, Zhao Y, Lee HZ. Molecular modelling, synthesis, cytotoxicity and anti-tumour mechanisms of 2-aryl-6-substituted quinazolinones as dual-targeted anti-cancer agents. Br J Pharmacol. 2013; 169: 1574–1586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Sarkar J, Singh N, Meena S, Sinha S. Staurosporine induces apoptosis in human papillomavirus positive oral cancer cells at G2/M phase by disrupting mitochondrial membrane potential and modulation of cell cytoskeleton. Oral Oncol. 2009; 45: 974–979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Carlson RO. New tubulin targeting agents currently in clinical development. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2008; 17: 707–722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Tsui L, Fong TH, Wang IJ. The effect of 3-(5’-hydroxymethyl-2’- furyl)-1-benzylindazole (YC-1) on cell viability under hypoxia. Mol Vis. 2013; 19: 2260–2273. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Huang YT, Pan SL, Guh JH, Chang YL, Lee FY, Kuo SC, et al. YC-1 suppresses constitutive nuclear factor-kappaB activation and induces apoptosis in human prostate cancer cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 2005; 4: 1628–1635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Zhang Q, Bian H, Guo L, Zhu H. Pharmacologic preconditioning with berberine attenuating ischemia-induced apoptosis and promoting autophagy in neuron. Am J Transl Res. 2016; 8: 1197–1207. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Yeh CH, Hsu SP, Yang CC, Chien CT, Wang NP. Hypoxic preconditioning reinforces HIF-alpha-dependent HSP70 signaling to reduce ischemic renal failure-induced renal tubular apoptosis and autophagy. Life Sci. 2010; 86: 115–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Wu J, Ke X, Wang W, Zhang H, Ma N, Fu W, et al. Aloe-emodin suppresses hypoxia-induced retinal angiogenesis via inhibition of HIF-1alpha/VEGF pathway. Int J Biol Sci. 2016; 12: 1363–1371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Chang LH, Pan SL, Lai CY, Tsai AC, Teng CM. Activated PAR-2 regulates pancreatic cancer progression through ILK/HIF-alpha- induced TGF-alpha expression and MEK/VEGF-A-mediated an- giogenesis. Am J Pathol. 2013; 183: 566–575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Liu YN, Pan SL, Peng CY, Guh JH, Huang DM, Chang YL, et al. YC-1 [3-(5’-hydroxymethyl-2’-furyl)-1-benzyl indazole] inhibits neointima formation in balloon-injured rat carotid through suppression of expressions and activities of matrix metalloproteinases 2 and 9. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006; 316: 35–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Shin DH, Kim JH, Jung YJ, Kim KE, Jeong JM, Chun YS, et al. Preclinical evaluation of YC-1, a HIF inhibitor, for the prevention of tumor spreading. Cancer Lett. 2007; 255: 107–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Kim HL, Yeo EJ, Chun YS, Park JW. A domain responsible for HIF-1alpha degradation by YC-1, a novel anticancer agent. Int J Oncol. 2006; 29: 255–260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Lau CK, Yang ZF, Lam SP, Lam CT, Ngai P, Tam KH, et al. Inhibition of Stat3 activity by YC-1 enhances chemo-sensitivity in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Biol Ther. 2007; 6: 1900–1907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Birkinshaw RW, Czabotar PE. The BCL-2 family of proteins and mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilisation. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Shakeri R, Kheirollahi A, Davoodi J. Apaf-1: Regulation and function in cell death. Biochimie. 2017; 135: 111–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Li P, Zhou L, Zhao T, Liu X, Zhang P, Liu Y, et al. Caspase-9: structure, mechanisms and clinical application. Oncotarget. 2017; 8: 23996–24008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Maes ME, Schlamp CL, Nickells RW. BAX to basics: How the BCL2 gene family controls the death of retinal ganglion cells. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2017; 57: 1–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. Ho TF, Chang CC. A promising “TRAIL” of tanshinones for cancer therapy. Biomedicine (Taipei). 2015; 5: 23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126. Harma V, Schukov HP, Happonen A, Ahonen I, Virtanen J, Siitari H, et al. Quantification of dynamic morphological drug responses in 3D organotypic cell cultures by automated image analysis. PLoS One. 2014; 9: e96426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127. Single A, Beetham H, Telford BJ, Guilford P, Chen A. A Comparison of Real-Time and Endpoint Cell Viability Assays for Improved Synthetic Lethal Drug Validation. J Biomol Screen. 2015; 20: 1286–1293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128. Bain JM, Louw J, Lewis LE, Okai B, Walls CA, Ballou ER, et al. Candida albicans hypha formation and mannan masking of beta-glucan inhibit macrophage phagosome maturation. MBio. 2014; 5: e01874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Effects of YC-1 on cell confluence in CAR cells. cclls were incubatcd with or without 100 μM of YC-1. The dyuamic ccll imaging was 3en by the IneuC’yte™ Kinetic Live Cell Imaging System at a 2 h interval and up to 48 h