Abstract

Objective

To estimate the future risk and time trends of newly diagnosed venous thromboembolism (VTE) in individuals with incident systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) in the general population.

Methods

Using a population-based database that includes all residents of British Columbia, Canada we conducted a study cohort of all patients with incident SLE and up to 10 age-, sex-, and entry-time-matched individuals from the general population. We compared incidence rates of pulmonary embolism (PE), deep venous thrombosis (DVT) and VTE between the two groups according to SLE disease duration. We calculated hazards ratios (HR), adjusting for confounders.

Results

Among 4,863 individuals with SLE (86% female, mean age 48.9 years), the incidence rates (IRs) of PE, DVT, and VTE were 2.58, 3.33, and 5.32 per 1000 person-years, respectively, whereas the corresponding rates in the comparison cohort were 0.67, 0.57, and 1.11 per 1000 person-years. Compared with non-SLE individuals, the multivariable HRs among SLE patients were 3.04 (95% CI, 2.08–4.45), 4.46 (95% CI, 3.11–6.41) and 3.55 (95% CI, 2.69–4.69), respectively. The age-, sex-, and entry time-matched HRs for PE, DVT and VTE were highest during the first year after SLE diagnosis (13.57 [95% CI, 7.66–24.02], 11.13 [95% CI, 6.55–18.90] and 12.89 [95% CI, 8.56–19.41], respectively).

Conclusion

These findings provide population-based evidence that patients with SLE have a substantially increased risk of VTE, especially in the first year after SLE diagnosis. Awareness and increased vigilance of this potentially fatal, but preventable, complication is recommended.

Keywords: Cardiovascular disease, systemic lupus erythematosus, deep venous thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, risk

INTRODUCTION

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a chronic autoimmune disease with a broad spectrum of autoantibodies and clinical manifestations. It is well known that the cardiovascular disease (CVD) morbidity and mortality of patients with SLE is substantially increased as compared to the general population [1–3]. Moreover, CVD occurs at a younger age in SLE patients than in the general population [3, 4].

To date, most of the studies that have searched for the underlying cause of CVD in major rheumatic diseases, including SLE, have focused mainly on premature atherosclerosis (e.g. increased risk of acute myocardial infarction or ischemic stroke), which is associated with the chronic inflammation in these diseases [5–7]. In contrast, there is limited data on the contemporary risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE) in SLE [8–11], especially at the general population level, despite several mechanisms by which rheumatic diseases can increase this risk. Like other autoimmune diseases, hypercoagulability and inflammation are general features of SLE, and both factors are responsible for inciting venous thrombosis.

Systemic inflammation can modulate thrombotic responses by upregulating procoagulants, downregulating anticoagulants and suppressing fibrinolysis [12]. Additionally, antiphospholipid antibodies, which are often seen in SLE, confer an increased risk of vascular events [1].

VTE encompasses both pulmonary embolism (PE) and deep vein thrombosis (DVT), both of which are major health concerns that have an annual incidence of 1–2 cases per 1000 people in western populations [13]. There is significant mortality associated with VTE events, up to 15% in the first 3 months after diagnosis [14, 15]. This makes VTE potentially as deadly an illness as acute myocardial infarction; survivors often experience serious and costly long-term complications from their illness, as well as potential side effects from anticoagulation treatment [16, 17]. Given that approximately 79% of patients who present with PE have evidence of DVT in their legs, PE and DVT are thought to represent the spectrum of one disease [18]. Furthermore, because PE can be largely prevented by preventing DVT, studying these conditions together is sensible.

Studies on VTE in SLE are limited and mainly come from tertiary care centres, thus limiting their generalizability [8, 9, 19–22]. In two hospital-based studies SLE was strongly associated with VTE risk [15, 23]. However, it is unknown whether this increased risk is generalizable to the unselected general population (i.e., regardless of hospitalization). To address this gap we estimated the risk of newly recorded DVT and PE among incident SLE cases compared to controls from the general population.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Data source

Universal health coverage is a feature of the province of British Columbia (BC, population ~ 4.7 million), Canada. Population Data BC captures population-based administrative data including: linkable data files on all provincially funded health care professional visits [24], hospital admissions and discharges [25], interventions [24], investigations [24], demographic data [26], cancer registry [27] and vital statistics [28] since 1990. Furthermore, Population Data BC encompasses the comprehensive prescription drug database, PharmaNet [29], with data since 1995. Numerous general population-based studies have been successfully conducted using these databases [30–34].

Study Design and Cohort Definitions

We conducted matched cohort analyses for incident VTE (PE or DVT) among individuals with incident SLE (SLE cohort) as compared with age-, sex-, and entry-time-matched individuals without SLE (comparison cohort) using data from Population Data BC. We created an incident SLE cohort with cases diagnosed for the first time between January 1996 and December 2010 defined as follows: a) two International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM 710.0) codes for SLE at least two months apart and within a two year period by a non-rheumatologist physician; b) One ICD-9-CM code for SLE by a rheumatologist or from hospital (ICD-9-CM 710.0 or ICD-10 M32.1, M32.8 and M32.9) and c) Absence of a prior SLE diagnosis between January 1990 and December 1995 (to ensure incident SLE cases). This SLE definition was used previously and found to have a sensitivity of 98.2%, a specificity of 73% [35] and positive predictive value of 90% in US Medicare part B data [36]. To further improve specificity we excluded individuals with at least two visits ≥ 2 months apart, subsequent to the SLE diagnostic visit, with diagnoses of other inflammatory diseases (e.g. rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, spondyloarthropathy). In addition, we excluded cases that did not have an ICD code for SLE within the last five years prior to the end of follow-up, as long as they remained alive and residents of the province (i.e. still using health care services). For the comparison cohorts we matched up to 10 individuals randomly without SLE to each SLE case based on age, sex, and calendar year of study entry.

Ascertainment of PE and DVT

Incident PE and DVT cases were defined by corresponding ICD codes and prescription of anticoagulant therapy (i.e. heparin, warfarin sodium or a similar agent)[37]. The codes used were as follows: PE (ICD-9-CM: 415.1, 673.2, 639.6 and ICD-10-CM: O88.2, I26), and DVT (ICD-9-CM: 453 and ICD-10-CM: I82.4, I82.9). Since VTE is a potentially fatal disease we also included patients with a fatal outcome. Because a patient may have died before anticoagulation treatment, patients with a recorded code of PE were included in the absence of recorded anticoagulant therapy if there was a fatal outcome within 1 month of diagnosis. This VTE definition has been found to have a confirmation rate of 94% in a UK general practice database[37].

Assessment of Covariates

Covariates consisted of potential risk factors of VTE assessed during the year before the index date (date of diagnosis) including: relevant medical conditions (obesity, alcoholism, hypertension, varicose veins, inflammatory bowel disease, fractures, sepsis, trauma, surgery), healthcare utilization (number of outpatient and hospital visits), use of glucocorticoids, hormone replacement therapy, contraceptives and COX-2 inhibitors. Additionally, a modified Charlson’s co-morbidity index for administrative data was calculated in the year before the index date [38, 39].

Cohort Follow-Up

Our study cohorts spanned the period of January 1, 1996 to December 31, 2010. Individuals with SLE entered the case cohort after all inclusion criteria had been met, and controls entered the comparison cohort after a matched doctor’s visit in the same calendar year. Participants were followed until they either experienced an outcome, died, dis-enrolled from the health plan (i.e. left the province), or the follow-up period ended (December 31, 2010), whichever occurred first.

Statistical Analysis

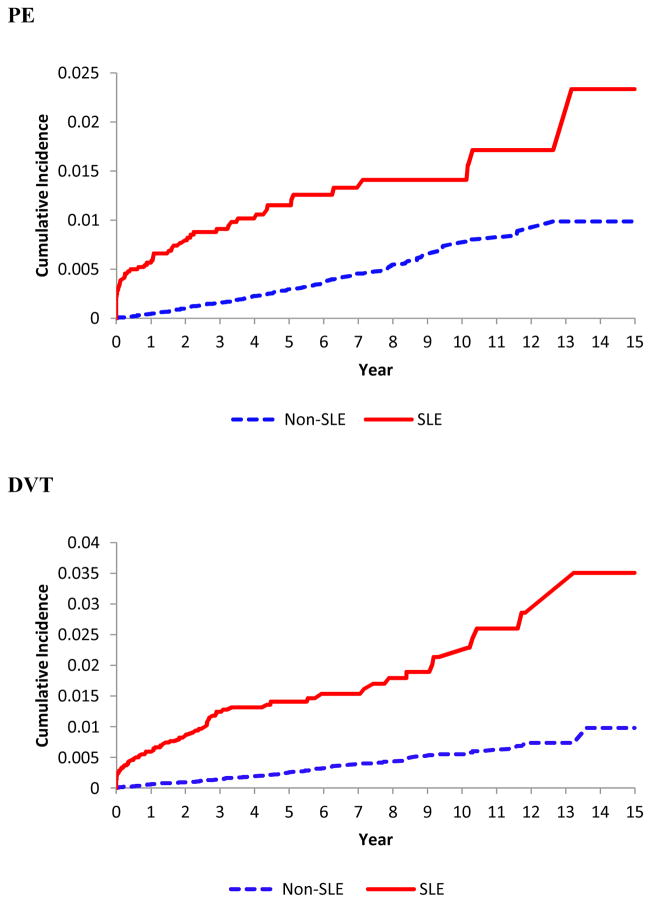

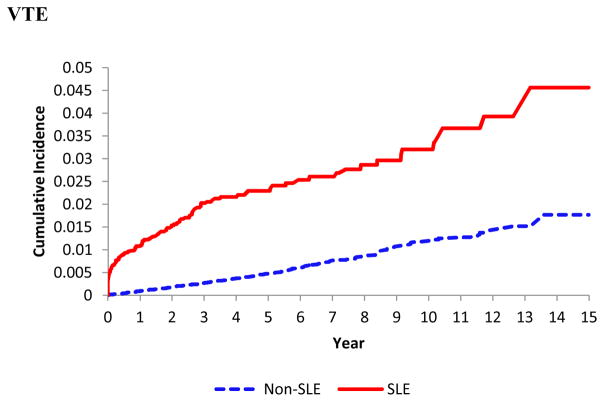

We compared baseline characteristics between the SLE and comparison cohorts. We identified incident cases of PE and DVT during the follow-up period and calculated incidence rates (IRs) of PE and DVT, both individually and in combination (i.e., VTE), per 1,000 person-years. We estimated the cumulative incidence of each event accounting for the competing risk of death by using the SAS macro CUMINCID and graphically presented these results[40]. We used Cox proportional hazard regression models to assess the risk of PE and DVT associated with SLE after adjusting for covariates. We entered confounders one at a time into the Cox models in a forward selection according to each confounder’s impact on the hazard ratio (HR) of SLE, relative to the HR in the model selected in the previous step. Cut-off for the minimum important relative effect at each step was set to 5%[41]. In order to evaluate the impact of duration of SLE (i.e., follow-up time after SLE diagnosis), we estimated the HR yearly for the first five years.

We performed two sensitivity analyses. Firstly, we estimated the cumulative incidence of each event accounting for the competing risk of death according to Lau et al. [42] and expressed the results as sub-distribution HRs with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Secondly, to quantify the potential impact of unmeasured confounders (e.g., antiphospholipid antibodies), we performed sensitivity analyses which assessed how a hypothetical unmeasured confounder might have affected our estimates of the association between SLE and the risk of VTE [43]. We simulated unmeasured confounders with prevalence’s ranging from 10% to 20% in the SLE and control cohorts, and odds ratios (ORs) for the associations between the unmeasured confounder, SLE and VTE ranging from 1.3 to 3.0. We used SAS Version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, USA) for all analyses. For all HRs, we calculated 95% CIs. All p-values were two sided.

No personal identifying information was made available as part of this study; procedures used were in compliance with British Columbia’s Freedom of Information and Privacy Protection Act. Ethics approval was obtained from the University of British Columbia.

RESULTS

Our primary analysis included 4,863 individuals with incident SLE and 49,838 age-, sex-, and entry-time-matched individuals in the comparison cohort. Table 1 summarizes the baseline characteristics of the case and comparison cohorts. Compared with the non-SLE group, the SLE group used glucocorticoids and COX-2 inhibitors more often, had higher Charlson’s co-morbidity indices and used more health care resources during the past 12 months.

Table 1.

Characteristics of SLE and Comparison cohorts at Baseline

| Variable | SLE N=4,863 |

Non-SLE N=49,838 |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean years) | 48.9 ± 16.3 | 48.9 ± 16.3 | 0.839 |

| Female | 4162 (85.6%) | 42606 (85.5%) | 0.881 |

| Hospitalized | 1418 (29.2) | 6583 (13.2) | <0.001 |

| Number of outpatient visits (mean) | 19.3 ± 17.4 | 7.7 ± 10.1 | <0.001 |

| Charlson’s Comorbidity Index | 0.95 ± 1.32 | 0.25 ± 0.90 | <0.001 |

| Alcoholism with liver disease | 53 (1.1) | 313 (0.6) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 954 (19.6) | 7724 (15.5) | <0.001 |

| Sepsis | 31 (0.6) | 52 (0.1) | <0.001 |

| Varicose veins | 64 (1.3) | 437 (0.9) | 0.003 |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | 37 (0.8) | 156 (0.3) | <0.001 |

| Trauma | 9 (0.2) | 67 (0.1) | 0.317 |

| Fractures | 80 (1.6) | 523 (1.0) | <0.001 |

| Surgery | 61 (1.3) | 400 (0.8) | 0.002 |

| Glucocorticoids | 1628 (33.5) | 1682 (3.4) | <0.001 |

| Hormone replacement therapy | 430 (8.8) | 2989 (6.0) | <0.001 |

| Oral Contraceptives | 358 (7.4) | 3721 (7.5) | 0.819 |

| Cox-2 inhibitors | 388 (8.0) | 1184 (2.4) | <0.001 |

Values are N (percentages) unless otherwise noted. SD: standard deviation, NS: Non-significant

Association between SLE and VTE

SLE was significantly associated with an increased incidence of PE, DVT, and VTE (Table 2 and Figure 1). Among 4,863 individuals with incident SLE, the IRs of PE, DVT and VTE were 2.58, 3.33, and 5.32 per 1000-person years, versus 0.67, 0.57, and 1.11, respectively, in the comparison cohort. The corresponding age-, sex-, and entry-time matched HRs were 4.46 (95% CI, 3.23–6.14), 6.69 (95% CI, 4.92–9.09) and 5.50 (95% CI, 4.35–6.94) with all p values <0.001. After further adjusting for other covariates the HRs for PE, DVT and VTE remained significant (all p values were <0.001) (Table 2). When we evaluated the impact of follow-up time after the SLE diagnosis, the HRs for PE, DVT, and VTE were substantially larger in the first year after the diagnosis of SLE compared to the following years (Table 3). Overall, the HRs for PE, DVT and VTE were 14, 11 and 13 times higher, respectively, in the first year after SLE diagnosis. Furthermore, HRs from all sensitivity analyses of the association between SLE and study outcomes after accounting for the competing risk of death and the potential impact of unmeasured confounders remained statistically significant (Table 4).

Table 2.

Relative Risk of Incident PE and DVT According to SLE Status

| SLE N=4863 |

Non-SLE N=49838 |

|

|---|---|---|

| PE | ||

| Cases, N | 53 | 139 |

| Incidence Rate/1000 Person-Years | 2.58 | 0.67 |

| Age-, Sex-, Entry Time-Matched Cox HR (95% CI) | 4.46 (3.23, 6.14) | 1.0 |

| Charlson-Adjusted Age-, Sex-, Entry Time-Matched Cox HR (95% CI) | 3.71 (2.65, 5.19) | 1.0 |

| Glucocorticoid-Adjusted Age-, Sex-, Entry Time-Matched Cox HR (95% CI) | 3.41 (2.34, 4.97) | 1.0 |

| * Fully-Adjusted Age-, Sex-, Entry Time-Matched Cox HR (95% CI) | 3.04 (2.08, 4.45) | 1.0 |

| DVT | ||

| Cases, N | 68 | 118 |

| Incidence Rate/1000 Person-Years | 3.33 | 0.57 |

| Age-, Sex-, Entry Time-Matched Cox HR (95% CI) | 6.69 (4.92, 9.09) | 1.0 |

| Charlson-Adjusted Age-, Sex-, Entry Time-Matched Cox HR (95% CI) | 5.58 (4.06, 7.68) | 1.0 |

| Glucocorticoid-Adjusted Age-, Sex-, Entry Time-Matched Cox HR (95% CI) | 5.50 (3.86, 7.82) | 1.0 |

| No. MSP visits-Adjusted Age-, Sex-, Entry Time-Matched Cox HR (95% CI) | 5.40 (3.92, 7.45) | 1.0 |

| * Fully-Adjusted Age-, Sex-, Entry Time-Matched Cox HR (95% CI) | 4.46 (3.11, 6.41) | 1.0 |

| VTE | ||

| Cases, N | 108 | 229 |

| Incidence Rate/1000 Person-Years | 5.32 | 1.11 |

| Age-, Sex-, Entry Time-Matched Cox HR (95% CI) | 5.50 (4.35, 6.94) | 1.0 |

| Charlson-Adjusted Age-, Sex-, Entry Time-Matched Cox HR (95% CI) | 4.56 (3.58, 5.82) | 1.0 |

| Glucocorticoid-Adjusted Age-, Sex-, Entry Time-Matched Cox HR (95% CI) | 4.34 (3.31, 5.70) | 1.0 |

| No. MSP visits-Adjusted Age-, Sex-, Entry Time-Matched Cox HR (95% CI) | 4.49 (3.51, 5.74) | 1.0 |

| * Fully-Adjusted Age-, Sex-, Entry Time-Matched Cox HR (95% CI) | 3.55 (2.69, 4.69) | 1.0 |

Fully-adjusted models include the following selected covariates.

PE: Charlson and glucocorticoids; DVT: Charlson, No. MSP visits and glucocorticoids; PE or DVT: Charlson, No. MSP visits and glucocorticoids

Figure 1.

Cumulative incidence of pulmonary embolism (upper panel), deep vein thrombosis (middle panel) and venous thromboembolism (lower panel) in the 4,863 patients with incident systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) as compared with the 49,838 age-, sex- entry-time-matched non-SLE subjects.

Table 3.

Age and sex adjusted Cox HRs for PE, DVT or both (VTE) in SLE according to follow-up period

| Time after diagnosis | PE HR (95% CI) |

DVT HR (95% CI) |

VTE HR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| <1 year | 13.57 (7.66, 24.02) | 11.13 (6.55, 18.90) | 12.89 (8.56, 19.41) |

| <2 years | 9.34 (5.97, 14.63) | 9.91 (6.37, 15.42) | 10.08 (7.25, 14.01) |

| <3 years | 7.27 (4.87, 10.86) | 10.02 (6.84, 14.69) | 8.88 (6.66, 11.84) |

| <4 years | 6.29 (4.32, 9.15) | 8.72 (6.08, 12.50) | 7.72 (5.88, 10.12) |

| <5 years | 5.82 (4.07, 8.31) | 7.74 (5.49, 10.93) | 6.93 (5.34, 8.99) |

| Total follow-up | 4.46 (3.23, 6.14) | 6.69 (4.92, 9.09) | 5.50 (4.35, 6.94) |

HR= Hazard ratio

Table 4.

Sensitivity Analyses, HR (95% CI)

| Outcome | Primary analysis | Sub-distribution Cox model | Simulated confounder 10%/OR=1.3 | Simulated confounder 10%/OR=3.0 | Simulated confounder 20%/OR=1.3 | Simulated confounder 20%/OR=3.0 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PE | 3.04 (2.08, 4.45) | 2.93 (2.02, 4.25) | 3.02 (2.06, 4.41) | 2.50 (1.69, 3.68) | 3.04 (2.08, 4.45) | 2.64 (1.79, 3.90) |

| DVT | 4.46 (3.11, 6.41) | 4.16 (2.94, 5.89) | 4.50 (3.13, 6.46) | 3.92 (2.71, 5.67) | 4.50 (3.14, 6.46) | 3.54 (2.44, 5.12) |

| VTE | 3.55 (2.69, 4.69) | 3.45 (2.63, 4.54) | 3.54 (2.68, 4.67) | 2.92 (2.20, 3.88) | 3.56 (2.70, 4.70) | 2.98 (2.24, 3.96) |

Primary analysis is the fully-adjusted model; Sub-distribution models are adjusted for the same covariates as the primary analysis in addition to age and sex; simulated confounder models included additional covariates per the selection algorithm

DISCUSSION

This is the first general population-based study evaluating the risk of VTE in patients with incident SLE. In this large cohort we found that the risk of VTE events, including PE and DVT, are substantially increased in the SLE population when compared to the age-, sex-, and entry time-matched controls. SLE cases had a 3–4 fold increased risk of PE, DVT and VTE. The increased risk was the highest during the first year after SLE diagnosis (14-, 11- and 13-fold for PE, DVT and VTE, respectively). These risks were independent of traditional risk factors for VTE.

The finding of increased VTE among patients with SLE could have important implications for clinical care, both immediately after a diagnosis of SLE and in long-term treatment. Our findings imply that a diagnosis of SLE should alert clinicians to be mindful of possible thrombotic events, particularly in the period soon after diagnosis. Our results are in agreement with two recent studies that used hospital-based samples [15, 23] (Table 5). In a Swedish study, Zoller et al. focused only on the risk of PE in 9,147 patients with SLE; they found an increased risk of PE, with it being the greatest during the first year of follow-up (standardized incidence rate ratio= 10.23, 2.11, 1.56, 1.10 for <1 year, 1–5 years, 5–10 years and ≥10 years of follow-up, respectively). These findings are remarkably similar to ours despite the difference in the study population (hospitalized versus general population) and the inability of the Zoller et al. study to adjust for important VTE risk factors such as various comorbid diseases and medication use.

Table 5.

Studies assessing the risk of venous thromboembolism in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus

| Author (Year) | N SLE | Study Design | Sample Type | Risk (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| DVT | PE | VTE | ||||

| Mok (2010)[21] | 516 | Cohort | Hospital | -- | -- | 11.9 (7.3–19.6) |

| Chung (2014) [44] | 13,084 | Cohort | Catastrophic Illness Registry | 12.8 (9.06–18.1) | 19.7 (11.9–32.8) | -- |

| Ramagopalan (2011)[45] | a594 | Cohort | Hospital | -- | -- | a 3.61 (2.36–5.31) |

| b 997 | b 2–4.60 (3.19–6.43) | |||||

| c 23,544 | c 3.71 (3.43–4.02) | |||||

| Zoller (2012)[15] | 9,147 | Cohort | Hospital | -- | 2.20 (1.95–2.47) | -- |

| Johannesdottir (2012)[23] | 27 | Case-control | Hospital | -- | -- | 2.8 (1.7–4.7) |

| Current study (2015) | 4,863 | Cohort | Population-based | 4.46 (3.11–6.41) | 3.04 (2.08–4.45) | 3.55 (2.69–4.69) |

CI: confidence interval

SLE: systemic lupus erythematosus

DVT: deep vein thrombosis

PE: pulmonary embolism

VTE: venous thromboembolism

ORLS1-Oxford Record Linkage study database (includes data from 1963–1998)

ORLS2-Oxford Record Linkage study database (includes data from 1999–2008)

England-the complete dataset of the English national hospital episode statistics (1999–2008)

Johannesdottir et al. [23] evaluated the risk of VTE in a number of autoimmune skin and connective tissue diseases in a case control study using the Danish National Patient Registry. They found that SLE had the greatest overall risk for VTE among all autoimmune diseases, with a 2.8-fold risk compared to matched controls. This study did not examine the time trend risks after the diagnosis and only identified SLE cases from hospital admissions. Moreover, both the Johannesdottir and Zoller et al. studies did not use incident cases or anticoagulation use in their case definition of VTE, both of which have been shown to improve the accuracy of diagnosis [46]. Furthermore, these studies did not adjust for competing risks or unmeasured confounders.

The mechanism for VTE in SLE is multifactorial. Venous thrombosis is slightly less frequent and has a different clinical presentation than arterial thrombosis; this suggests that the underlying risk factors and mechanism of thrombosis are different and vary over time [9]. In 1856, Virchow proposed three precipitants for venous thrombosis: venous stasis, increased coagulability of the blood, and damage to the vessel wall [47, 48]. Inflammatory rheumatic conditions, such as SLE, could affect venous stasis or increase coagulability of the blood through decreased mobility and inflammation-associated mechanisms. For example, inflammation modulates thrombotic responses by upregulating procoagulants, downregulating anticoagulants, and suppressing fibrinolysis [12].

Inflammatory rheumatic disorders may have additional underlying VTE pathophysiology, such as inflammatory damage to the vessel wall due to venulitis or the presence of antiphospholipid antibodies[1]. Moreover, older age, shorter disease duration, disease activity over time, and higher dose of glucocorticoids are additional risk factors for VTE [19].

Strengths and limitations of our study deserve comment. Beyond being the first large general population investigation of a critically important outcome in a relatively uncommon connective tissue disease, our study was based on nearly the entire BC population; therefore our findings are likely generalizable to the population at large. However, uncertainty around diagnostic accuracy cannot be completely ruled out. We may have false-positive SLE cases in our cohort, as we did not use the gold standard for SLE diagnosis, the American College of Rheumatology criteria, to identify SLE [49]. Nevertheless, we used one of the strictest case definitions available for administrative databases, using both diagnostic codes and additional exclusion criteria. Moreover, more than 80% of cases came from hospitals or rheumatologists.

Although we adjusted for all known risk factors for VTE available in our data, our database did not have other potential confounders like body mass index or antiphospholipid antibodies, and this is an important limitation. However our findings persisted in our sensitivity analyses for potential impact of plausible ranges of these unmeasured confounders. Having said this, our results could still be affected by unknown or unmeasured confounders, similar to other observational studies.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, this is the first comprehensive, truly general population-based study assessing the risk of VTE in a large incident cohort of SLE. Compared to the risk in the general population, our SLE cohort had a 3-fold increased risk for PE, a 4-fold increased risk of DVT and a 3-fold increased risk of overall VTE. The risk was higher in the first year after the diagnosis. These results call for awareness of this complication and increased vigilance. The role of preventive intervention by controlling the inflammatory process, or by anticoagulation measures, in a high-risk SLE population deserves further research.

Acknowledgments

We want to thank Kathryn Reimer for her editorial assistance in the preparation of this manuscript. All inferences, opinions and conclusions drawn in this article are those of the authors, and do not reflect the opinions or policies of the Data Stewards.

Funding: This study was funded by the Canadian Arthritis Network and the British Columbia Lupus Society (Grant 10-SRP-IJD-01) and the Canadian Institutes for Health Research (Grants MOP 125960 and THC 135235). Dr. Avina-Zubieta is the British Columbia Lupus Society Research Scholar and a Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research Scholar.

Footnotes

Role of Sponsors: None other than funding the research.

Contributors: JAA-Z secured the funding source, and contributed to study conception, study design, data analysis/interpretation, and critical review of the manuscript. KV and MDV contributed to data analysis/interpretation and drafted the manuscript. ES contributed to data analysis and manuscript preparation. HKC secured some of the funding sources, and contributed to study conception/design, data analysis/interpretation, and critical review of the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript

References

- 1.Lundström E, Gustafsson JT, Jönsen A, Leonard D, Zickert A, Elvin K, Sturfelt G, Nordmark G, Bengtsson AA, Sundin U, et al. HLA-DRB1*04/*13 alleles are associated with vascular disease and antiphospholipid antibodies in systemic lupus erythematosus. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72(6):1018–1025. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-201760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cervera R, Khamashta M, Font J, Sebastiani G, Gil A, Lavilla P, Mejia J, Aydintug A, Chwalinska-Sadowska H, de Ramon E, et al. Morbidity and mortality in systemic lupus erythematosus during a 10-year period. A comparison of early and late manifestations in a cohort of 1000 patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 2003;82:299– 308. doi: 10.1097/01.md.0000091181.93122.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Manzi S, Meilahn EN, Rairie JE, Conte CG, Medsger TA, Jansen-McWilliams L, D’Agostino RB, Kuller LH. Age-specific incidence rates of myocardial infarction and angina in women with systemic lupus erythematosus: comparison with the Framingham study. Am J Epidemiol. 1997;145(5):408–415. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McMahon M, Hahn BH, Skaggs BJ. Systemic lupus erythematosus and cardiovascular disease: prediction and potential for therapeutic intervention. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2011;7(2):227–241. doi: 10.1586/eci.10.98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aviña-Zubieta JA, Abrahamowicz M, Choi HK, Rahman MM, Sylvestre MP, Esdaile JM, Lacaille D. Risk of cerebrovascular disease associated with the use of glucocorticoids in patients with incident rheumatoid arthritis: a population-based study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70(6):990–995. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.140210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.del Rincón ID, Williams K, Stern MP, Freeman GL, Escalante A. High incidence of cardiovascular events in a rheumatoid arthritis cohort not explained by traditional cardiac risk factors. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44(12):2737–2745. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200112)44:12<2737::AID-ART460>3.0.CO;2-%23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Solomon DH, Curhan GC, Rimm EB, Cannuscio CC, Karlson EW. Cardiovascular risk factors in women with and without rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50(11):3444–3449. doi: 10.1002/art.20636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brouwer JL, Bijl M, Veeger NJ, Kluin-Nelemans HC, van der Meer J. The contribution of inherited and acquired thrombophilic defects, alone or combined with antiphospholipid antibodies, to venous and arterial thromboembolism in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Blood. 2004;104(1):143–148. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-11-4085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chang ER, Pineau CA, Bernatsky S, Neville C, Clarke AE, Fortin PR. Risk for incident arterial or venous vascular events varies over the course of systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol. 2006;33(9):1780–1784. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mok CC, Ho LY, To CH. Annual incidence and standardized incidence ratio of cerebrovascular accidents in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Scand J Rheumatol. 2009;38(5):362–368. doi: 10.1080/03009740902776927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Romero-Díaz J, García-Sosa I, Sánchez-Guerrero J. Thrombosis in systemic lupus erythematosus and other autoimmune diseases of recent onset. J Rheumatol. 2009;36(1):68–75. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.071244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xu J, Lupu F, Esmon CT. Inflammation, innate immunity and blood coagulation. Hamostaseologie. 2010;30(1):5–6. 8–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deitelzweig SB, Johnson BH, Lin J, Schulman KL. Prevalence of clinical venous thromboembolism in the USA: current trends and future projections. Am J Hematol. 2011;86(2):217–220. doi: 10.1002/ajh.21917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wong P, Baglin T. Epidemiology, risk factors and sequelae of venous thromboembolism. Phlebology. 2012;27(Suppl 2):2–11. doi: 10.1258/phleb.2012.012s31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zöller B, Li X, Sundquist J, Sundquist K. Risk of pulmonary embolism in patients with autoimmune disorders: a nationwide follow-up study from Sweden. Lancet. 2012;379(9812):244–249. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61306-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goldhaber SZ. DVT Prevention: what is happening in the “real world”? Semin Thromb Hemost. 2003;29(Suppl 1):23–31. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-45414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van der Poll T, de Boer JD, Levi M. The effect of inflammation on coagulation and vice versa. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2011;24(3):273–278. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e328344c078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tapson VF. Acute pulmonary embolism. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(10):1037–1052. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra072753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Calvo-Alén J, Toloza SM, Fernández M, Bastian HM, Fessler BJ, Roseman JM, McGwin G, Vilá LM, Reveille JD, Alarcón GS, et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus in a multiethnic US cohort (LUMINA). XXV. Smoking, older age, disease activity, lupus anticoagulant, and glucocorticoid dose as risk factors for the occurrence of venous thrombosis in lupus patients. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52(7):2060–2068. doi: 10.1002/art.21149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Levy DM, Massicotte MP, Harvey E, Hebert D, Silverman ED. Thromboembolism in paediatric lupus patients. Lupus. 2003;12(10):741–746. doi: 10.1191/0961203303lu458oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mok CC, Ho LY, Yu KL, To CH. Venous thromboembolism in southern Chinese patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin Rheumatol. 2010;29(6):599–604. doi: 10.1007/s10067-009-1364-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Somers E, Magder LS, Petri M. Antiphospholipid antibodies and incidence of venous thrombosis in a cohort of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol. 2002;29(12):2531–2536. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johannesdottir SA, Schmidt M, Horváth-Puhó E, Sørensen HT. Autoimmune skin and connective tissue diseases and risk of venous thromboembolism: a population-based case-control study. J Thromb Haemost. 2012;10(5):815–821. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2012.04666.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.British Columbia Ministry of Health [creator] Medical Services Plan (MSP) Payment Information File. Population Data BC [publisher]. Data Extract. MOH (2013) 2013 http://www.popdata.bc.ca/data.

- 25.British Columbia Ministry of Health [creator] Discharge Abstract Database (Hospital Separations). Population Data BC [pubisher]. Data Extract. MOH (2013) 2013 http://www.popdata.bc.ca/data.

- 26.British Columbia Ministry of Health [creator] Consolidation File (MSP Registration & Premium Billing). Population Data BC [publisher]. Data Extract. MOH (2013) 2013 https://www.popdata.bc.ca/data.

- 27.BC Cancer Agency Registry Data. Data Extract. BC Cancer Agency; 2014. Population Data BC [publisher] (2013) http://www.popdata.bc.ca/data. [Google Scholar]

- 28.BC Vital Statistics Agency [creator] Vital Statistics Deaths. Population Data BC [publisher] Data Extract BC Vital Statistics Agency. 2012 (2013) http://www.popdata.bc.ca/data.

- 29.BC Ministry of Health [creator] Data Extract. Data Stewardship Committee; 2013. PharmaNet. BC Ministry of Health [publisher] (2013) http://www.popdata.bc.ca/data. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Solomon DH, Massarotti E, Garg R, Liu J, Canning C, Schneeweiss S. Association between disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs and diabetes risk in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and psoriasis. JAMA. 2011;305(24):2525–2531. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Avina-Zubieta JA, Abrahamowicz M, De Vera MA, Choi HK, Sayre EC, Rahman MM, Sylvestre MP, Wynant W, Esdaile JM, Lacaille D. Immediate and past cumulative effects of oral glucocorticoids on the risk of acute myocardial infarction in rheumatoid arthritis: a population-based study. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2013;52(1):68–75. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kes353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Etminan M, Forooghian F, Brophy JM, Bird ST, Maberley D. Oral fluoroquinolones and the risk of retinal detachment. JAMA. 2012;307(13):1414–1419. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.De Vera MA, Choi H, Abrahamowicz M, Kopec J, Goycochea-Robles MV, Lacaille D. Statin discontinuation and risk of acute myocardial infarction in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a population-based cohort study. Ann Rheum Dis. 70(6):1020–1024. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.142455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aviña-Zubieta JACH, Abrahamowicz A, Rahman M, Sylvestre MP, Esdaile JM, Lacaille D. Risk of cerebrovascular disease associated with the use of glucocorticoids in patients with incident rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70:990–995. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.140210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bernatsky S, Linehan T, Hanly JG. The accuracy of administrative data diagnoses of systemic autoimmune rheumatic diseases. J Rheumatol. 2011;38(8):1612–1616. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.101149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Katz JN, Barrett J, Liang MH, Bacon AM, Kaplan H, Kieval RI, Lindsey SM, Roberts WN, Sheff DM, Spencer RT, et al. Sensitivity and positive predictive value of medicare part B physician claims for rheumatologic diagnoses and procedures. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40(9):1594–1600. doi: 10.1002/art.1780400908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huerta C, Johansson S, Wallander MA, Garcia Rodriguez LA. Risk factors and short-term mortality of venous thromboembolism diagnosed in the primary care setting in the United Kingdom. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(9):935–943. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.9.935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chron Dis. 1987;40(5):373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Romano PS, Roos LL, Jollis JG. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative data: differing perspectives. J Clin Epidemiol. 1993;46(10):1075–1079. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(93)90103-8. discussion 1081–1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gooley TA, Leisenring W, Crowley J, Storer BE. Estimation of failure probabilities in the presence of competing risks: new representations of old estimators. Statist Med. 1999;18(6):695–706. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19990330)18:6<695::aid-sim60>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bursac Z, Gauss CH, Williams DK, Hosmer DW. Purposeful selection of variables in logistic regression. Source Code Biol Med. 2008;3(17) doi: 10.1186/1751-0473-3-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lau B, Cole SR, Gange SJ. Competing risk regression models for epidemiologic data. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;170(2):244–256. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schneeweiss S. Sensitivity analysis and external adjustment for unmeasured confounders in epidemiologic database studies of therapeutics. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2006;15(5):291–303. doi: 10.1002/pds.1200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chung W, Lin C, Chang S, Lu C, Kao C. Systemic lupus erythematosus increases the risk of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism: nationwide cohort study. J Thromb Haemost. 2014;12:452–458. doi: 10.1111/jth.12518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ramagopalan S, Wotton C, Handel A, Yeates D, Goldacre M. Risk of venous thromboembolism in people admitted to hospital with selected immune-mediated diseaes: record linkage study. BMC Med. 2011;9(1) doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-9-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Huerta C, Johansson S, Wallander MA, Garcia Rodriguez LA. Risk factors and short-term mortality of venous thromboembolism diagnosed in the primary care setting in the United Kingdom. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(9):935–943. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.9.935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brotman DJ, Deitcher SR, Lip GY, Matzdorff AC. Virchow’s triad revisited. South Med J. 2004;97(2):213–214. doi: 10.1097/01.SMJ.0000105663.01648.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Smeeth L, Cook C, Thomas S, Hall AJ, Hubbard R, Vallance P. Risk of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism after acute infection in a community setting. Lancet. 2006;367(9516):1075–1079. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68474-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.1997 update of 1982 Revised Criteria for classification of SLE [file:///C:/Users/Katuxa/Downloads/1997_update_of_the_1982_acr_revised_criteria_for_classification_of_sle%20(1).pdf]