Abstract

A 50-year-old female was diagnosed with vulvar cancer treated with left partial vulvectomy and bilateral lymphadenectomy. Ten months after her surgery, she presented with increased labial swelling, pain and discharge. Biopsy confirmed recurrence of squamous cell vulvar carcinoma. Incidentally, on restaging radiographic scans, she was found to have a large right ventricular mass which, after surgical debulking, was shown to be a squamous cell cancer of vulvar origin. She was commenced on chemotherapy with carboplatin and paclitaxel along with concurrent radiation therapy. Restaging PET scan showed persistent metastatic disease. She was switched to Cisplatin/Taxol after having hypersensitivity reaction to Carboplatin. She received 5 cycles with progression of disease in the follow up scans. She then received Nivolumab for 2 cycles. The patient then opted for comfort directed care given worsening functional status and progression of disease on repeat imaging. Secondary cardiac tumors are very rare and not extensively studied in oncology. Therefore, optimal management is not entirely clear. It is extremely rare for vulvar cancer to metastasize to the heart and only two cases have been reported in the literature. However, vulvar cancer metastasizing to the right ventricular cavity and endocardium has not been described before. We believe that this is the first ever such reported case.

Keywords: Vulvar cancer, Squamous cell cancer, Cardiac metastasis

Highlights

-

•

Only 15% of recurrent vulvar cancers metastasize to distant sites.

-

•

Cardiac metastasis from vulvar cancer is exceedingly rarely.

-

•

Evidence regarding management of cardiac metastasis from vulvar cancer is limited.

1. Introduction

Vulvar carcinoma is a rare gynecological malignancy with a propensity to recur locally in most cases. However, distant recurrences can occur. We describe a case of 50-year-old Caucasian female who had intra-cardiac and pulmonary recurrences of a surgically resected FIGO Stage 1 squamous cell carcinoma. This case is unique due to its exceedingly rare presentation and challenging management.

2. Case

The patient is a 50-year-old nulliparous female with history of well controlled asthma and cigarette smoking who initially presented to the oncologist with recently diagnosed squamous cell cancer of the vulva. At the time of diagnosis, her symptoms included redness, itching and burning around the vulva unrelieved by the use of various antifungal and steroid creams. She was then seen by her gynecologist and a left vulvar biopsy was performed which showed keratinizing moderately differentiated infiltrating squamous cell carcinoma. Staging computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans showed localized disease without pelvic lymphadenopathy and no distant metastases. She underwent left partial vulvectomy and bilateral inguinal lymphadenectomy since intraoperative sentinel lymph node could not be identified with isosulfan blue injection. Microscopic examination of the resected specimens revealed 9 mm deep, 2.1 cm moderately differentiated, squamous cell cancer and a focus of positive cancerous margin adjacent to the urethral meatus. All the seven resected lymph nodes were negative for any cancer. Given the positive margin, she underwent distal urethrectomy three months after the initial diagnosis which failed to reveal any tumor.

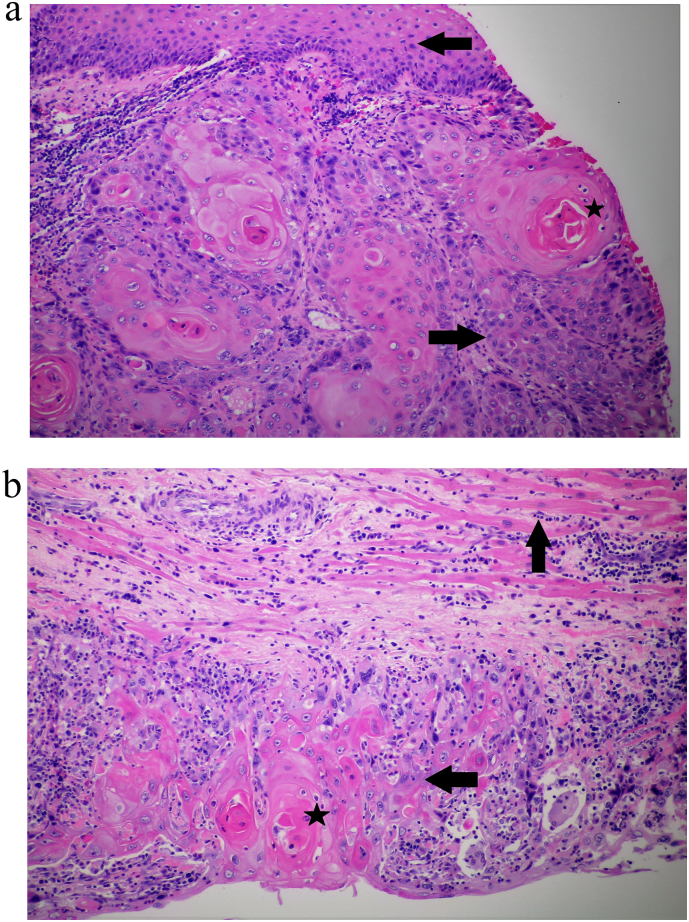

The patient, six months after initial diagnosis of FIGO (International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics) stage 1b, T1b N0 M0, vulvar carcinoma, developed swelling of the labia and increased drainage around the genital area. She attributed the swelling to postoperative vulvar lymphedema and declined further evaluation including biopsy. However, over the next 4 months, her symptoms worsened with increasing swelling and pain in the genital area. An examination under anesthesia demonstrated bilateral labial swelling, erythema, ulcerated lesions and serosanguinous discharge. Biopsy showed recurrence of invasive vulvar squamous cell cancer (Fig. 1a).

Fig. 1.

a Microscopic view of vulvar biopsy demonstrating squamous cell carcinoma (rightward black arrow) and several keratin pearls (black star). Normal vulvar squamous epithelium is indicated by the leftward black arrow. b Microscopic view of RV mass biopsy showing infiltration by squamous cell cancer (leftward black arrow) along with keratin pearls (black star). Normal myocardium is indicated by black upward arrow.

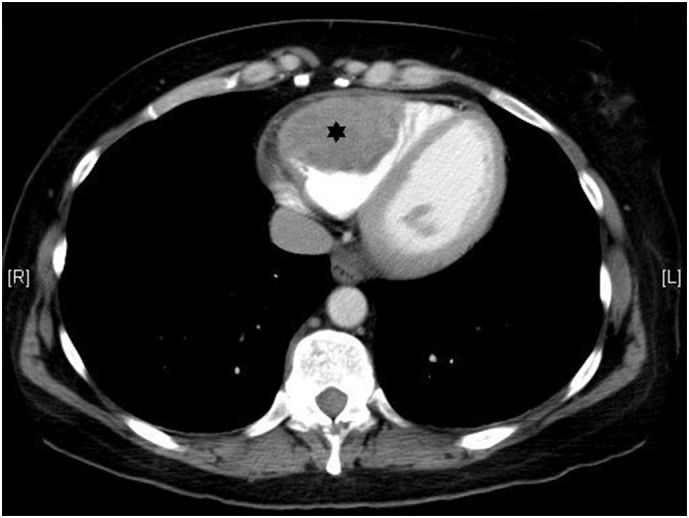

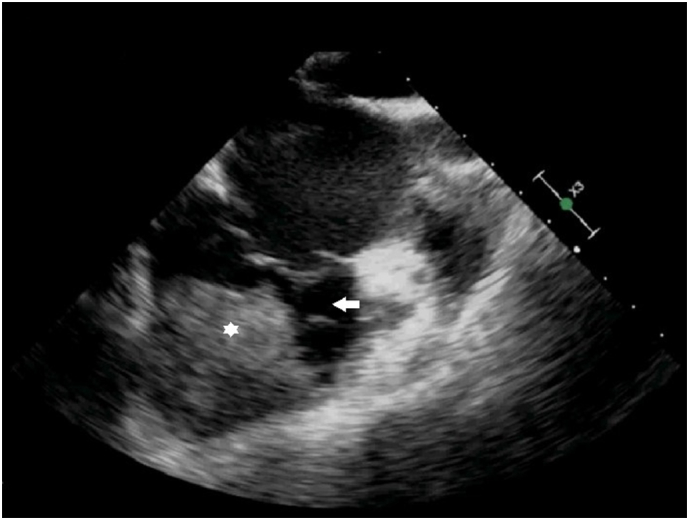

A computed tomography (CT) scan of chest, abdomen & pelvis for restaging interestingly demonstrated a 6.8 × 4.9 × 6.2 cm mass in the right ventricle (RV) (Fig. 2). Echocardiogram (Fig. 3) confirmed the presence of a large RV mass adherent to the free wall extending from the base to the apex with a 2 × 1.8 cm mobile component. In addition, CT scan showed multiple pulmonary emboli and multiple sub-centimeter and one 1.6 cm cavitary pulmonary nodules concerning for metastatic disease. CT scan of the pelvis showed bilateral inguinal adenopathy and left vulvar thickening, consistent with recurrent disease.

Fig. 2.

CT scan of the chest showing dilated RV with a large hetergenously attenuated intracavitary mass with lobulated contours (black star).

Fig. 3.

Echocardiogram showing the same mass (white star) and right ventricular cavity (white arrow).

A differential diagnosis of intra-cardiac thrombus, primary cardiac tumor such as myxoma or sarcoma and metastatic cardiac tumor were considered. Particularly interesting was the lack of cardiac or pulmonary symptoms despite a large intra-cardiac mass. Therapeutic anticoagulation with intravenous unfractionated heparin was commenced. Immediate cardiothoracic surgery evaluation was undertaken given the size and location of the RV mass and high risk of embolization. A decision to surgically resect the mass was made, however, to the surprise of the surgeon, the mass was found to be densely adherent to the RV muscular wall without associated thrombus. Therefore, it was not amenable to surgical resection and only debulking was performed which showed well differentiated squamous cell cancer consistent with vulvar origin (Fig. 1b) confirming recurrent vulvar cancer with cardiac and pulmonary metastases.

Postoperative course was complicated by anemia treated with red cell transfusion and urinary tract infection treated with antibiotics. Towards the end of her two-week hospitalization, she developed new-onset atrial fibrillation controlled with beta blockers. In regards to her vulvar cancer, chemotherapy and radiotherapy were contemplated. She received her first dose of weekly chemotherapy regimen, consisting of low dose carboplatin and paclitaxel as inpatient which was continued after discharge for a total of 5 doses. Furthermore, concurrent pelvic radiotherapy was given with chemotherapy. Since most of her symptoms were related to local recurrence in the form of erythema, induration and extreme pain of the external gentalia, therefore, even though the patient had metastatic vulvar carcinoma, the rationale for radiotherapy was primarily palliative or pseudo-curative (radiation dose was 180 cGy).

After completing chemo-radiotherapy, a positron emission tomography (PET) scan showed residual vulvar disease with inguinal lymphadenopathy, persistent RV mass and increased pulmonary nodule size with peak standardized uptake values (SUV) of 8.1, 6.4 and 2.7, respectively. Full dose carboplatin and paclitaxel was then initiated but after her first full dose carboplatin, she developed an immediate hypersensitivity reaction. Carboplatin was switched to cisplatin. Her disease remained stable after 3 cycles of Cisplatin and Taxol. Bevacizumab was contemplated but in light of her recent open heart surgery and sternotomy, and risks of non-healing and bleeding associated with it, decision was made to defer it. She then developed peripheral neuropathy which became so severe that Chemotherapy had to be stopped after 5 cycles of cisplatin/Taxol. Repeat imaging studies at this point revealed progression of metastatic disease in lungs. The decision was made to stop chemotherapy. The next generation sequencing of her tumor revealed that 25% of the cells expressed PDL-1. At this point of her disease, decision was made to start her on Nivolumab. Before the start of third cycle of Nivolumab, the patient presented to the hospital with acute hypoxemic respiratory failure. Imaging revealed extensive progression of the disease and the patient opted for hospice and comfort directed care. The patient passed away peacefully 3 weeks later.

3. Discussion

Vulvar cancer is a rare gynecological malignancy in elderly women with an annual incidence of 2–3 per 100,000 women. An increase in the incidence of vulvar cancer in recent decades is a reflection of increase in its risk factors such as human papilloma virus, smoking, immunosuppressive states and lichen sclerosus (Woelber et al., 2013). Among various histologic types of vulvar cancer, squamous cell cancer is the most common. Local spread to regional nodes occurs via lymphatic embolization relatively early in the course of disease while distant metastases occur late via hematogenous dissemination (Ansink, 1996). In a retrospective analysis, recurrence rate was found to be 37.7%. Most recurrences occurred locally or regionally in the pelvis; distant recurrences or metastases were found only in 15% of patients (Maggino et al., 2000). Most recurrences occur within two years of initial surgical management (Maggino et al., 2000). Distant metastases in vulvar cancer to lung, skin, muscles, liver, kidney, breast and central nervous system have been reported (Agrawal et al., 2013). Vulvar cancer metastasizing to the heart is an extremely rare event that, to our knowledge, has been reported in two patients in the English medical literature (Hanbury, 1960, Htoo and Nanton, 1973) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Case reports of vulvar cancer metastasizing to heart.

| Hanbury WJ (Hanbury, 1960) | Htoo MM et al. (Htoo and Nanton, 1973) | Present case | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 63 | 70 | 50 |

| Initial treatment | Radical vulvectomy | Vulvectomy | Left partial vulvectomy |

| Inguinal lymphadenopathy | Present | Unknown | Absent |

| Histological type of vulvar cancer | Squamous cell cancer | Squamous cell cancer | Squamous cell cancer |

| Time to recurrence | 7 months | 4 months | 10 months |

| Location of cardiac metastasis | Numerous metastases in epicardium, myocardium and endocardium | Atrioventricular groove and right atrial subendocardium | Right ventricular endocardium, myocardium and intracavitary |

| Clinical presentation of cardiac metastasis | Atrial fibrillation | Complete heart block | No cardiac manifestations; pulmonary thromboembolism |

| Treatment of recurrence | None | None | Tumor debulking |

| Outcome | Died on presentation | Died on presentation | Died after failure of chemo- and immunotherapy |

Cardiac tumors are classified as primary and secondary, and have not been investigated extensively in clinical oncology owing to their rarity. Primary cardiac tumors are a rare entity with incidence of 0.3%–0.7% of all cardiac tumors as per various surgery and autopsy reports (Leja et al., 2011). However, metastasis of a primary malignancy to the heart is 30 times more common. Theoretically, any malignancy can metastasize to the heart with a highly variable reported overall incidence of 2.3%–18.3% (Bussani et al., 2007). In a post-mortem report of about 19,000 patients from 1994 to 2003, an incidence of cardiac metastasis of 9% was found (Bussani et al., 2007). Most common primary tumors with high potential for cardiac metastasis include lung cancers, melanoma, pleural mesothelioma, esophageal cancer, breast cancer, malignant lymphoproliferative neoplasms, gastric carcinomas, renal carcinomas and pancreatic carcinomas (Leja et al., 2011). Gynecological malignancies have also been associated with metastasis to the heart, albeit very rarely. Cardiac metastases have been reported in ovarian (Leja et al., 2011) and uterine cancers (Artioli et al., 2016, Tsuchida et al., 2016). To our knowledge, endocardial and intracavitary metastasis secondary to recurrent metastatic squamous cell cancer of vulvar has not been reported.

Cardiac metastasis most commonly involves the pericardium and epicardium comprising two thirds of all cardiac metastases (Butany et al., 2005), however, involvement of myocardium, endocardium, cardiac cavities, great vessel and coronaries can also occur (Bussani et al., 2007, Reynen et al., 2004, Lam et al., 1993). Intracavitary metastasis are very rare representing less than 5% of all cardiac metastases (Bussani et al., 2007, Lam et al., 1993). Most common route is direct invasion of locally advanced malignant tumors in the intrathoracic cavity such as lung, mesothelium and esophagus. Besides, hematogenous, lymphatic and transvenous extension (direct extension of hepatocellular and renal cell carcinoma via inferior vena cava) are other pathways (Bussani et al., 2007). Clinical presentation varies depending on the location of the metastatic lesion in the heart. However, since majority of cardiac metastasis are small, they usually remain clinically silent. When present, clinical symptoms are a result of reduced ventricular filling, ventricular outflow tract obstruction, conduction abnormalities and thromboembolisation (Reynen et al., 2004).

Despite absence of infiltration of inguinal lymph nodes and distal urethra by the cancer, the patient had recurrence locally as well as distally at an extremely rare site. In addition, our patient is the only case of vulvar cancer with intracavitary cardiac metastasis mimicking intra-cardiac thrombus. Furthermore, despite a large right ventricular mass, cardiac specific signs and symptoms were lacking. While small metastases are usually clinically silent, larger lesions are most often associated with cardiac symptoms. We believe that the numerous pulmonary emboli were cardiac in origin, associated with the mass. It is important to realize that radiographic differentiation between a cardiac mass or thrombus can be difficult (Motwani et al., 2013) and critical treatment decisions have to be made at times as in this case.

There are currently trials going on for immunotherapy in gynecological cancers with PD-1 inhibitors Nivolumab and Pembrolizumab. Preliminary results of Phase 1b KEYNOTE Study – 028 (Frenel et al., 2016) does show promising results in cervical squamous cell cancer with the use of PD-1 inhibitor Pembrolizumab. In our patient, PDL-1 positivity was 25%. Unfortunately, her disease progressed after two cycles of Nivolumab and she opted for hospice.

References

- Agrawal A., Wood K.A., Giede C.K. A case of kidney metastasis in vulvar squamous cell carcinoma: a case report and review of literature. Case Rep. Clin. Med. 2013;2:306–309. [Google Scholar]

- Ansink A. Vulvar squamous cell carcinoma. Semin. Dermatol. 1996;15:51. doi: 10.1016/s1085-5629(96)80019-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Artioli G., Borgato L., Calamelli S. Unusual cardiac metastasis of uterine leiomyosarcoma: case report and literature review. Tumori. 2016;25(4):306–312. doi: 10.5301/tj.5000498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bussani R., De-Giorgio F., Abbate A. Cardiac metastases. J. Clin. Pathol. 2007;60(1):27–34. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2005.035105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butany J., Leong S.W., Carmichael K. A 30-year analysis of cardiac neoplasms at autopsy. Can. J. Cardiol. 2005;21:675–680. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frenel J., Tourneau C., O'Neil B. Pembrolizumab in patients with advanced cervical squamous cell cancer: Preliminary results from the phase Ib KEYNOTE-028 study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016;34 (suppl; abstr 5515) [Google Scholar]

- Hanbury W.J. Secondary tumours of the heart. Br. J. Cancer. 1960;14:23–27. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1960.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Htoo M.M., Nanton M.A. Complete heart block due to disseminated vulval carcinoma. Br. Heart J. 1973;35(11):1211–1213. doi: 10.1136/hrt.35.11.1211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam K.Y., Dickens P., Chan A.C. Tumors of the heart. A 20-year experience with a review of 12,485 consecutive autopsies. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 1993;117(10):1027–1031. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leja M.J., Shah D.J., Reardon M.J. Primary cardiac tumors. Tex. Heart Inst. J. 2011;38(3):261–262. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maggino T., Landoni F., Sartori E. Patterns of recurrence in patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva. Cancer. 2000;89:116–122. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20000701)89:1<116::aid-cncr16>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motwani M., Kidambi A., Herzog B.A. MR imaging of cardiac tumors and masses: a review of methods and clinical applications. Radiology. 2013;268:26–43. doi: 10.1148/radiol.13121239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynen K., Köckeritz U., Strasser R.H. Metastases to the heart. Ann. Oncol. 2004;15(3):375–381. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdh086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuchida K., Oike T., Ohtsuka T. Solitary cardiac metastasis of uterine cervical cancer with antemortem diagnosis: a case report and literature review. Oncol. Lett. 2016;11(5):3337–3341. doi: 10.3892/ol.2016.4415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woelber L., Trillsch F., Kock L. Management of patients with vulvar cancer: a perspective review according to tumour stage. Ther. Adv. Med. Oncol. 2013;5(3):183–192. doi: 10.1177/1758834012471699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]