Highlights

-

•

Hemobilia is a very rare emergency. Among non-iatrogenic causes pseudoaneurysm of cystic artery should be considered.

-

•

Knowledge of anatomical variations of cystic artery is fundamental in hepatobiliary surgical and radiologic procedures.

-

•

Because of extreme rarity of the aneurysms of cystic artery there are no guidelines about their management and treatment.

Keywords: Case report, Hemobilia, Pseudoaneurysm cystic artery, Interventional radiology, Anatomic variant splanchnic arteries

Abstract

Introduction

Hemobilia represents only 6% of all causes of upper gastrointestinal bleeding.

Presentation of case

We report a rare case of a bleeding pseudoaneurysm of the cystic artery, due to a re-activation of a chronic cholecystitis, which arose with a mixed symptomatology: jaundices and hematemesis.

Discussion

The rarity of our patient is increased for some vascular anatomic variations detected by Computed Tomography that influenced the management of the disease.

Our patient was treated by endovascular embolization of the pseudoaneurysm and subsequent cholecystectomy.

Conclusion

About pseudoaneurysm of the cystic artery only few cases have been already reported and to date there are no guidelines for its management.

We describe both diagnostic features and therapeutic strategies in comparison to the most recent literature.

1. Introduction

In surgical practice jaundice and hematemesis are two symptoms apparently with little in common. When they occur in the same patient diagnosis is challenging.

Hemobilia triggered by non-iatrogenic injuries of the cystic artery is an extreme rare but possible etiology and therefore it should be considered.

We report the case of a bleeding pseudoaneurysm of the cystic artery due to a re-activation of a chronic cholecystitis treated by endovascular embolization and subsequent cholecystectomy.

Management of pseudoaneurysm of the cystic artery is controversial for the lack of guidelines. We explain our experience in comparison to the most recent literature.

Our work is in line with the SCARE criteria [1] and the PROCESS criteria [2].

2. Presentation of case

A 64-years-old male came to our attention with acute pain in right upper quadrant of abdomen and vomit. Clinical examination showed oral mucosa and conjunctiva jaundiced.

His laboratory data demonstrates mild anemia (Hemoglobin: 12 mg/dl), elevated transaminases (GPT: 277 U/l; GOT: 190 U/l) and obstructive jaundice (total bilirubin: 5,7 mg/dl; direct bilirubin: 4,7 mg/dl).

Ultrasound examination of the abdomen revealed several gallstones, each smaller than one centimeter, in the gallbladder.

Our diagnosis was biliary colic and the patient was hospitalized.

After one day in stable conditions, he had curiously an attack of haematemesis and melaena. His laboratory data showed a worsening anemia (Hemoglobin: 9,3 mg/dl) requiring an urgent blood transfusion.

He underwent a gastroscopy that surprisingly showed a normal appearance of both stomach and duodenum. Instead, at the exploration of the ampulla of Vater, it was recognized a secretion made up of bright red blood mixed with bile.

Therefore we diagnosed a haemobilia.

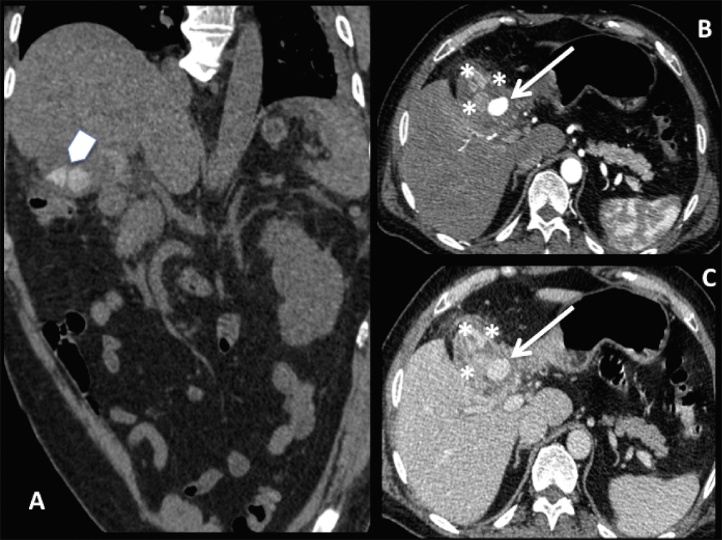

A Computed Tomography (CT) examination was performed and showed large gallstones [Fig. 1A]. After e.v. administration of the contrast medium a round hypervascular small mass, arising from the cystic artery, appeared inside the gallbladder: it consisted of a pseudoaneurysm [Fig. 1B]. Hypothesis of cholecystitis was suggested by thick and irregular cholecystic walls and inhomogeneous perivisceral fat [Fig. 1C].

Fig. 1.

CT examination: coronal pre-contrast image (A); axial arterial (B) and portal (C) phase images. Arrowhead in A shows some large gallstones. After administration of the contrast medium the pseudoaneurysm appeared inside the gallbladder as a round mass with the same density of the arteries (arrows in B e C). Thick and irregular cholecystic walls with inhomogeneous perivisceral fat (asterisks in B e C) suggested us the hypothesis of cholecystitis.

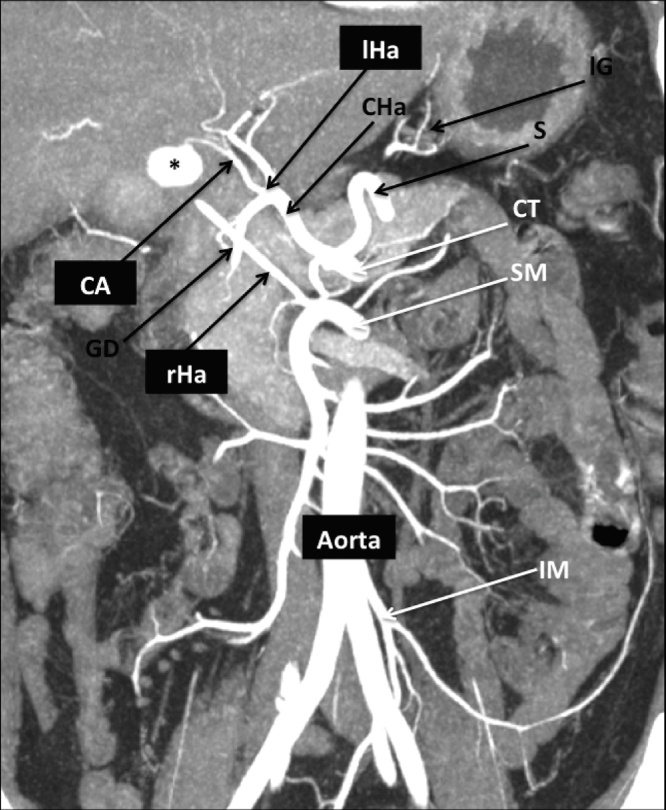

CT images showed also some anomalies of the splanchnic arterial district [Fig. 2] characterized by:

-

•

the right hepatic artery (rHa) arising from the superior mesenteric artery (SMa);

-

•

the left hepatic artery (lHa) arising from the common hepatic one, after the gastroduodenal artery;

-

•

the cystic artery (CA) arising from the lHa.

Fig. 2.

This coronal MIP post-processed computed tomography image clearly summarizes the particular vascular anatomy of our patient.

Asterisk shows the pseudoaneurysm of the CA that origin from the lHa; the rHa independently arise from the SM.

CT = celiac trunk; SM = superior mesenteric; IM = inferior mesenteric; S = splenic; lG = left gastric; CHa = common hepatic artery; GD = gastroduodenal; rHa = right hepatic artery; lHa = left hepatic artery; CA = cystic artery.

We concluded that the pseudoaneurysm, probably caused by a re-activation of chronic cholecystitis, was responsible for the hemobilia.

To avoid the risk of a new hemorrhage, we performed immediately the percutaneous embolization of the pseudoaneurysm.

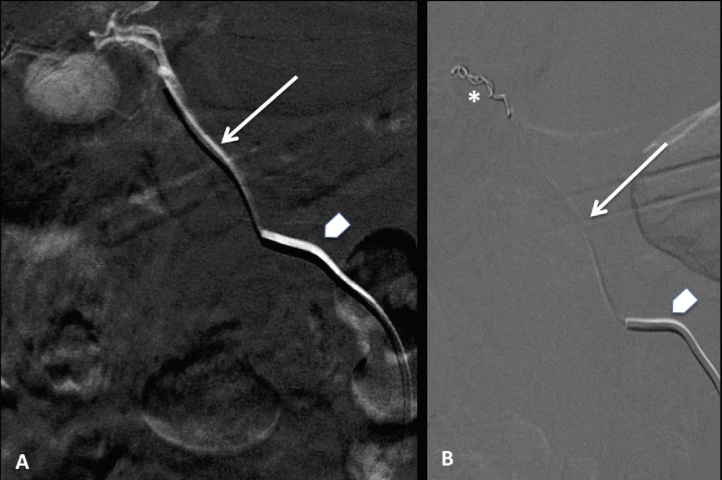

Thanks to the multiple vascular anatomic variations of our patients, we easily catheterized the CA through the lHa, rather than through the rHa arising from the SMa. Embolization was achieved positioning two micro-coils (VortX-18 Fibered Platinum Coil, Boston Scientific) at the origin of the pseudoneurysm by a micro-catheter (Terumo Progreat microcatheter) [Fig. 3].

Fig. 3.

Embolization of the pseudoanerysm was achieved using a coaxial system with a 5F Cobra catheter positioned at the origin of the lHa (arrowheads) and a micro-catheter advanced in the CA (arrows). Two micro-coils (asterisk in B) were placed in the neck and lumen of the pseudoanerysm that was finally excluded from circulation. lHa = left hepatic artery; CA = cystic artery.

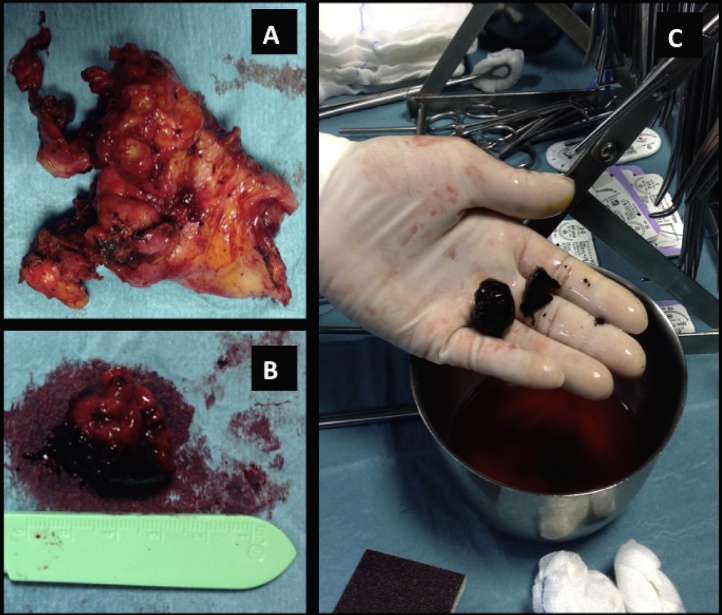

Then the patient was taken to the operating room for cholecystectomy. Laparoscopic approach was attempted but it was necessary conversion to laparotomy because strong adhesions hindered the mobilization of the gallbladder [Fig. 4].

Fig. 4.

After embolization of the pseudoaneurism, a colecistectomy was performed. Gallbladder (A) was fixed by strong adhesions to adiacent tissue and contained the collapsed pseudoanerism mass (B) and large gallstones (C).

No complication occurred in postoperative and the patient was discharged in sixth day.

3. Discussion

The term “hemobilia” refers to a bleeding into the biliary tree. It is traditionally characterized by the triad of symptoms: jaundice, abdominal pain and acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding (melena and hematemesis) [3].

Diagnosis is often challenging because manifestations may not be typical and can vary widely depending on site, entity and duration of the bleeding: consequently there are massive form, characterized by hemorrhagic shock representing a medical emergency, and mild form, in which exiguous but prolonged bleedings can cause anaemia and obstructive clots in the biliary tree with jaundice, acute pancreatitis, acute cholangitis or cholecystitis [4].

In our case the clinical onset was represented by obstructive jaundice with colic pain likely due to clots in the choledocus; then erosion of the CA and its active bleeding inside the gallbladder lumen caused hematemesis.

However, hemobilia is very uncommon representing only 6% of all causes of upper gastrointestinal bleeding [5]. Its main aetiology is the iatrogenic injury, recently increased for more frequent surgical and interventional procedures on hepatobiliary district, followed by trauma, tumors (hepatocellular carcinoma, cholangiocarcinoma, pancreatic adenocarcinoma, cancer of the gallbladder and liver metastases), inflammatory conditions and vascular abnormalities [6].

Pseudoaneurysm of the CA is a very rare cause of hemobilia and its pathogenesis is still unclear. Cholecystitis could produce necrosis and weakness of the arterial wall leading to its formation [7].

The most recent review about pseudoaneurysm of CA secondary to acute and chronic cholecystitis was proposed by Loizides, which collected less than 25 cases already reported in literature from 1983 to 2015 [8].

To the best of our knowledge, only three other similar cases have been subsequently reported from 2015 to date [9], [10], [11].

In our patients the gastroscopy showed a bleeding from the biliary system and then the CT examination demonstrated a bleeding pseudoaneurysm of the CA probably due to a re-activation of a chronic cholecystitis by gallstones. Furthermore CT angiography and in particular post-processed MIP images showed also some vascular variations giving essential information for planning of the therapeutic approach.

Anatomic variants of both hepatic and cystic arteries are due to a different vascular arranging of the splanchnic district in the embryo compared to the adult.

In the embryo, there are a lHA arising from the left gastric artery, a rHa from the SMa and a middle hepatic artery from the celiac axis. Then, the left and right embryological arteries regress and the middle one gives rise to the left and the right hepatic artery observed in the adults. The failure of this complex mechanism is responsible for the most common anatomic abnormality, such as supplementary hepatic arterial branches that do not originate from the celiac axis, the common or the proper hepatic artery [12].

Normally, the CA origins from the rHa and is located in the Calot’s triangle, an anatomic space bordered by the liver superiorly, the hepatic duct medially and the cystic duct laterally.

Anatomic variations of the CA are very important in hepato-biliary surgery.

Relationship between CA and Calot’s triangle was first clarified by Suzuki [13].

In 2007, Ding [14] classified its variations in three groups based on the results of numerous laparoscopies:

-

•

Group 1: normal anatomy of the Calot’s triangle with CA from rHa (80–96% of cases)

-

•Group 2: CA does not reach the gallbladder within the Calot’s triangle because it originates from:

-

○the gastroduodenal artery (“low-lying cystic artery”)

-

○

-

•

an aberrant rHa

-

•

the liver parenchyma

-

•

the lHa

-

•

Group 3: there are two CAs, one inside and one outside of the Calot’s triangle.

Instead to our knowledge only two works have already reported about the role of CT in the preoperative assessment of CA: Sugita et al. [15] detected CA from lHa in the 6% of their cases, Xia et al. [16] in the 10%.

According to these classifications, our case is a combination of two coexisting conditions: CA from the lHa with an aberrant rHa.

Knowledge of exact liver vasculature is mandatory for interventional radiologists [17], [18]. Curiously the anatomy of our patient helped us to perform the endovascular treatment of the pseudoaneurysm, because it was simpler catheterized the CA through celiac tripod and lHa rather than through the SMa and the aberrant rHa.

Because of the extreme rarity of the aneurism of the CA, there are no guidelines about clinical management and treatment [19].

Angiography is an important therapeutic option because allow embolization of the cystic pseudoaneurysm, converting an emergency situation to a semi-elective one. It has a high percentage of success reaching hemostasis in 75%–100% of patients with hemobilia [20] with a reported complication of less than 2% [21].

Several embolization techniques have already suggested [22], [21]: micro-coils are the most used while micro-particles are associated with an increased risk of ischemia of the gallbladder [23].

Actually there is not a universal consensus if embolization can be the definitive treatment or an intermediate step before cholecystectomy and ligation of the CA [24].

Although some authors affirm that the most feared complication of the embolization is the gallbladder necrosis and so suggest the necessity of a second therapeutic step with surgery [25], the case of a hyperselective embolization alone has been also reported [26].

However, as in our case, after stopping the bleeding of the pseudoaneurysm, a final colecistectomy is often mandatory to treat the triggering disease, such as cholecystitis, cholangitis or cancer.

4. Conclusion

Hemobilia by fissuring of a pseudoaneurysm of the CA is a very rare condition.

Consequently only few cases have been already reported in the literature, lacking guidelines and standardized procedures to manage it.

Our case is a brilliant example of the importance of interventional radiology in the urgent treatment of this affection, allowing hemodynamic stabilization of the patient and a safer surgery without risk of intraoperative bleeding.

A multidisciplinary collaboration between Radiologists and Surgeons is the key-point to the better management of these patients.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Funding source

None.

Ethical approval

Nothing to declare because our paper is a case report and not a research study.

Consent

This paper does not include case details or other personal information or images of our patient. But, if required, we can contact the patient to obtain his informed consent for publication.

Author contribution

Trombatore Claudia and Trombatore Pietro: writing and review of the paper.

Petrillo Giuseppe and Magnano S. Lio Vincenzo: radiological diagnosis and endovascular treatment of our patient. They participated to the study concept or design.

Scilletta Roberto and Bellavia Noemi: writing and review of the paper.

Di Cataldo Antonio: surgical management of our patient. He participated to the study design and review of the paper.

Guarantor

None.

Contributor Information

Claudia Trombatore, Email: claudiatr84@libero.it.

Roberto Scilletta, Email: robertoscilletta@gmail.com.

Noemi Bellavia, Email: noemibellavia@hotmail.it.

Pietro Trombatore, Email: pietro.tr@hotmail.it.

Vincenzo Magnano S. Lio, Email: v.magnano@alice.it.

Giuseppe Petrillo, Email: pucciopetrillo@hotmail.com.

Antonio Di Cataldo, Email: dicataldoa@tiscali.it.

References

- 1.Agha R.A., Fowler A.J., Saetta A., Barai I., Rajmohan S., Orgill D.P., SCARE Group The SCARE statement: consensus-based surgical case report guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2016;34:180–186. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2016.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Agha Riaz A., Fowler Alexander J., Rajmohan Shivanchan, Barai Ishani, Orgill Dennis P., SCARE Group Preferred reporting of case series in surgery; the PROCESS guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2016;36:319–323. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2016.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sandblom P. Hemorrhage into the biliary tract following trauma; traumatic hemobilia. Surgery. 1948;24:571–586. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chin M.W., Hemobilia Enns R. Curr. Gastroenterol. Rep. 2010;12:121–129. doi: 10.1007/s11894-010-0092-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dallal H.J., Palmer H.R. ABC of the upper gastrointestinal tract. Upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage. BMJ. 2001;323:1115. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7321.1115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yoshida J., Donahue P.E., Nyhus L.M. Hemobilia: review of recent experience with a worldwide problem. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 1987;82:448–453. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liang X., Lü Jm Meng N., Jin R., Cai X. Hemorrhagic shock caused by rupture of cystic artery pseudoaneurysm secondary to calculous cholecystitis. Chin. Med. J. 2013;126(23):4590–4591. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Loizides S., Ali A., Newton R., Singh K.K. Laparoscopic management of a cystic artery pseudoaneurysm in a patient with calculus cholecystitis. Int. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2015;14:182–185. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2015.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.She W.H., Tsang S., Poon R., Cheung T.T. Gastrointestinal bleeding of obscured origin due to cystic artery pseudoaneurysm. Asian J. Surg. 2015;20:1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.asjsur.2015.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Muñoz-Villafranca C., García-Kamirruaga Í., Góme-García P., Atín-del-Campo V., Bárcena-Robredo V., Aguinaga-Alesanco A., Calderón-García Á. Pseudoaneurysm of the cystic artery: an uncommon cause of upper gastrointestinal bleeding in a case of xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis. Rev. Esp. Enferm. Dig. 2015;107(June (6)):375–376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shelmerdine S.C., Ameli-Renani S., Lynch J.O., Gonsalves M. Transarterial catheter embolisation for an unusual cause of upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage. BMJ Case Rep. 2015 doi: 10.1136/bcr-2014-206837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Van den Hoven A.F., Van Leeuwen M.S., Lam M.G.E.H., Van den Bosch M.A.A.J. Springer Science+Business Media New York and the Cardiovascular and Interventional Radiological society of Europe (CIRSE); 2014. Hepatic Arterial Configuration in Relation to the Segmental Anatomy of the Liver; Observations on MDCT and DSA Relevant to Radioembolization Treatment. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Suzuki M., Akaishi S., Rikiyama T., Naitoh T., Rahman M.M., Matsuno S. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy, Calot’s triangle,and variations in cystic arterial supply. Surg. Endosc. 2000;14:141–144. doi: 10.1007/s004649900086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ding Y.M., Wang B., Wang W.X., Wang P., Yan J.S. New classification of the anatomic variations of the cystic artery during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. World J. Gastroenterol. 2007;13(42):5629–5634. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i42.5629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sugita R., Yamazaki T., Fujita N., Naitoh T., Kobari M., Takahashi S. Cystic artery and cystic duct assessment with 64-detector ow CT before laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Radiology. 2008;248:124–131. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2481071156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xia J., Zhang Z., He Y., Qu J., Yang J. Assessment and classification of cystic arteries with 64-detector row computed tomography before laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg. Radiol. Anat. 2015;37:1027–1034. doi: 10.1007/s00276-015-1479-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Polguj M., Podgórski M., Topol M. Variations of the hepatobiliary vasculature including coexistence of accessory right hepatic artery with unusually arising double cystic arteries: case report and literature review. Anat. Sci. Int. 2014;89:195–198. doi: 10.1007/s12565-013-0219-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Covey A., Brody L.A., Maluccio M.A., Getrajdman G.I., Brown K.T. Variant hepatic arterial anatomy revisited: digital subtraction angiography performed in 600 patients. Radiology. 2002;224:542–547. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2242011283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Anand U., Thakur S.K., Kumar S., Jha A., Prakash V. Idiopathic cystic artery aneurysm complicated with hemobilia. Ann. Gastroenterol. 2011;24(2):134–136. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Green M.H., Duell R.M., Johnson C.D., Jamieson N.V. Haemobilia. Br. J. Surg. 2001;88:773–786. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.2001.01756.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Priya H., Anshul G., Alok T., Saurabh K., Ranjit N., Romesh L., Deborshi S. Emergency cholecystectomy and hepatic arterial repair in a patient presenting with haemobilia and massive gastrointestinal haemorrhage due to a spontaneous cystic artery gallbladder fistula masquerading as a pseudoaneurysm. BMC Gastroenterol. 2013;13:43. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-13-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mullen R., Suttie S.A., Bhat R., Evgenikos N., Yalamarthi S., McBride K.D. Microcoil embolisation of mycotic cystic artery pseudoaneurysm: a viable option in high-risk patients. Cardiovasc. Intervent. Radiol. 2009;32(12759) doi: 10.1007/s00270-009-9590-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hague J., Brennand D., Raja J., Amin Z. Cystic artery pseudoaneurysms in hemorrhagic acute cholecyctitis. Cardiovasc. Intervent. Radiol. 2010;33:1287–1290. doi: 10.1007/s00270-010-9861-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Saluja S.S., Ray S., Gulati M.S., Pal S., Sahni P., Chattopadhyay T.K. Acute cholecystitis with massive upper gastrointestinal bleed: a case report and review of the literature. BMC Gastroenterol. 2007;7:12. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-7-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nana G.R., Gibson M., Speirs A., Ramus J.R. Upper gastrointestinal bleeding: a rare complication of acute cholecystitis. Int. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2013;4(9):761–764. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2013.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mokranea F.Z., Garcia Alba C., Lebbadia M., Mejdoubia M., Moulabbic M., Lombard F., Lengelléd F., Aveillane M. Pseudoaneurism of the cystic artery treated with hyperselective embolisation alone. Diagn. Interven. Imaging. 2013;94(6):641–643. doi: 10.1016/j.diii.2012.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]