Abstract

Cerebral venous oxygen saturation (SvO2) is an important biomarker of brain function. In this study, we aimed to explore the relative changes of regional cerebral SvO2 among axonal injury (AI) patients, non-AI patients and healthy controls (HCs) using quantitative susceptibility mapping (QSM). 48 patients and 32 HCs were enrolled. The patients were divided into two groups depending on the imaging based evidence of AI. QSM was used to measure the susceptibility of major cerebral veins. Nonparametric testing was performed for susceptibility differences among the non-AI patient group, AI patient group and healthy control group. Correlation was performed between the susceptibility of major cerebral veins, elapsed time post trauma (ETPT) and post-concussive symptom scores. The ROC analysis was performed for the diagnostic efficiency of susceptibility to discriminate mTBI patients from HCs.

The susceptibility of the straight sinus in non-AI and AI patients was significantly lower than that in HCs (P < 0.001, P = 0.004, respectively, Bonferroni corrected), which may indicate an increased regional cerebral SvO2 in patients. The susceptibility of the straight sinus in non-AI patients positively correlated with ETPT (r = 0.573, P = 0.003, FDR corrected) while that in AI patients negatively correlated with the Rivermead Post Concussion Symptoms Questionnaire scores (r = − 0.582, P = 0.018, FDR corrected). The sensitivity, specificity and AUC values of susceptibility for the discrimination between mTBI patients and HCs were 88%, 69% and 0.84. In conclusion, the susceptibility of the straight sinus can be used as a biomarker to monitor the progress of mild TBI and to differentiate mTBI patients from healthy controls.

Abbreviations: TBI, traumatic brain injury; mTBI, mild traumatic brain injury; AI, axonal injuries; SvO2, venous oxygen saturation; QSM, quantitative susceptibility mapping; HCs, healthy controls; ETPT, elapsed time post trauma; RPQ, Rivermead Post-Concussion Symptoms Questionnaire; Hct, hematocrit

Keywords: Mild traumatic brain injury, Axonal injury, Regional cerebral venous oxygen saturation, Susceptibility weighted imaging, Quantitative susceptibility mapping, Post-concussive symptom

Highlights

-

•

Mild traumatic brain injury caused decreased venous susceptibility.

-

•

The venous susceptibility can discriminate mTBI patients from healthy controls.

-

•

Decreased susceptibility may indicate increased venous oxygen saturation (SvO2).

-

•

Increased SvO2 of patients without axonal injury decreased with time post-injury.

-

•

Increased SvO2 of axonal injury patients indicated severe post-concussive symptoms.

1. Introduction

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is one of the major health problems worldwide and affects over 1.7 million people each year in the United States alone (Faul et al., 2010). It is estimated that 70–90% of TBI cases is mild TBI (mTBI), which is defined by a Glasgow Coma Scale of 13 to 15. This includes those cases where the period of loss of consciousness is < 30 min and the period of post-traumatic amnesia is < 24 h (Ahman et al., 2013). Mild brain injury can have serious post-concussion symptoms including headache, fatigue, dizziness, poor memory, depression, irritability and concentration difficulties. These symptoms can persist for several months to years and significantly affect the quality of life (Ahman et al., 2013, Doshi et al., 2015). Several serious cerebral changes associated with chronic mTBI have been reported, such as: axonal injuries (AI), decreased cerebral blood flow, cognitive dysfunction, chronic traumatic encephalopathy, Alzheimer's disease, changes of structural and functional connectivity, and abnormal oxygen metabolism (Barnes and Haacke, 2009, De Kruijk et al., 2001, Iraji et al., 2016, McAllister et al., 2001, Nordström et al., 2013, Takahata et al., 2016). Routine imaging is unable to find abnormalities in most cases. Hence, new methods are needed to evaluate physiological changes in the brain for mTBI patients with the hope of finding relevant information that could lead to a better diagnosis and prognosis.

Cerebral oxygenation is an important biomarker of brain function, because cerebral neurons depend predominantly on aerobic metabolism to meet their energy demand (Doshi et al., 2015). Consequently, increased cerebral venous oxygen saturation (SvO2) may indicate either a change in energy demand for traumatic cerebral tissues or an impaired ability to utilize oxygen. Another possibility may be that the increased cerebral blood flow in mTBI patients exceeds the oxygen demand of the cerebral tissues, indicating a neuroprotective response following mTBI (Doshi et al., 2015). Monitoring SvO2 may also reflect the therapeutic effect. For example, Sun et al. found the low brain tissue partial pressure of oxygen correlated with a poor outcome of severe TBI with mild hypothermia treatment (Sun et al., 2016). McCredie et al. found the treatment of red blood cell transfusion had no measurable impact on cerebral tissue oxygenation in severe TBI (McCredie et al., 2017). Therefore, the early detection of cerebral SvO2 changes may play a significant role in better understanding of the patient's pathologic changes. Near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) has been applied to detect the cerebral oxygenation in TBI patients. However, uncertainty still exists regarding the reliability of this technology, and it cannot detect the deep cerebral regional tissues oxygenation due to superficial coverage in the spectrophotometric methods (Davies et al., 2015, Ferrari et al., 2004).

Recently, quantitative susceptibility mapping (QSM) has been used to quantify the cerebral SvO2 (Haacke et al., 2010, Tang et al., 2013, Xu et al., 2014, Fan et al., 2014, Liu et al., 2017). Unlike other phase-based methods, the cerebral SvO2 from QSM is not dependent on the orientation of the cerebral veins. In previous studies, QSM has been used to explore the changes of regional cerebral SvO2 in a rat stroke model, healthy individuals and acute ischemic stroke patients (Buch et al., 2016, Hsieh et al., 2016, Xia et al., 2014). To date, only one paper has reported relative changes of cerebral SvO2 in mTBI patients (Doshi et al., 2015). In that study, Doshi et al. found the decreased venous susceptibility, indicating increased cerebral SvO2 in the left thalamostriate vein and right basal vein of Rosenthal in 14 mTBI patients.

The purposes of this study include: 1) to use QSM to measure the difference in the susceptibilities of major veins among the mTBI patients without AI, patients with AI and HCs; 2) to evaluate the diagnostic efficiency of susceptibility to discriminate mTBI patients from HCs; 3) to study the relationships between the susceptibility of major cerebral veins with ETPT and post-concussive symptom scores in mTBI patients.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Subjects profiles

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Tianjin First Central hospital. Written informed consent was acquired from all the subjects before the MRI study. Data from 49 mTBI patients were collected from August 2013 to April 2016. The inclusion criteria were made based on the definition of mTBI by the American Congress of Rehabilitation Medicine (1993), as follows: 1) the patients were right-handed and aged 18 years or older without contraindications for MR (such as any metal in the head and body, pacemaker, claustrophobia); 2) the patients had an initial Glasgow Coma Scale score of 13–15; 3) any period of loss of consciousness was approximately 30 min or less; 4) any period of post-traumatic amnesia in patients was < 24 h; 5) the patients may have changes of mental status, such as being disoriented, confused or dazed; 6) all patients had head CT data, and MRI data including T1-weighted and T2 FLAIR images (T1WI, T2 FLAIR), diffusion weighted imaging (DWI) and susceptibility weighted imaging (SWI); 7) CT imaging appearance of mTBI was negative; and 8) the patients did not have any other structural imaging changes except for AI, such as skull fracture, bleeding, cerebral contusion, hematoma, vessel malformation. The exclusion criteria were: 1) the age of patient was under 18 years; 2) the patient was pregnant; 3) the patients had a history of previous TBI; 4) the patient had another disorders including a neurological disease, brain tumor, epilepsy, seizure, drug or substance abuse, or any other systemic disease which might affect the cerebral oxygen metabolism; and 5) the imaging quality was too poor for observation and analysis because of motion artifact. According to the inclusion and exclusion criteria, one patient with poor imaging quality was excluded due to the motion artifacts in SWI images.

Finally, 48 mTBI patients (16 females, 32 males; age range 19 to 58 years; mean 35.38 ± 10.60 years) were recruited. The diagnostic criteria of AI included: 1) linear hypointensity on SWI or hyperintensity on T2WI and/or DWI and this abnormal signal was found on the interface between white and gray matter; 2) cerebral microbleeds or AI were found in the white matter of the cerebral cortex, corpus callosum, brainstem or cerebellum on SWI, which met with the mild AI classification of Adams (Adams et al., 1989, Davceva et al., 2015); and 3) there was no other brain damage such as: cerebral contusion, epidural or subdural hematoma or subarachnoid hemorrhage, etc. 16 AI patients were found in this group (6 females, 10 males, age range 19 to 56 years, mean 32.06 ± 10.00 years). The non-AI group was considered when no abnormalities were found on any MRI sequence (T1WI, T2 FLAIR, DWI or SWI), this included 32 patients (10 females, 22 males, age range from 19 to 58 years, mean 37.03 ± 10.65 years). Finally, the hematocrit (Hct) (0.27 to 0.50, mean 0.39 ± 0.04) and the ETPT (12 to 360 h, mean 70.73 ± 73.42 h) was recorded for all the patients. 32 HCs (12 females, 20 males, age range 20 to 59 years, mean 37.78 ± 9.81 years) were enrolled from the local community. They had no history of previous TBI, contraindications to MRI, neurological disorders, brain tumor, epilepsy, seizure, drug or substance abuse, or any other systematic diseases.

2.2. Post-concussive symptom scores

To evaluate the post-concussive symptoms after mTBI, the Rivermead Post-Concussion Symptoms Questionnaire (RPQ) (King et al., 1995) was given to all 48 patients within 24 h of admission by a neurosurgeon with 10-year experiences (R.G.). The RPQ test consists of 16 scoring items including headache, dizziness, nausea, noise sensitivity, sleep disturbance, fatigue, irritability, depression, frustration, poor memory, poor concentration, taking longer to think, blurred vision, light sensitivity, double vision and restlessness. These clinical symptoms were evaluated with a five-point scale corresponding to 5 response alternatives on an ordinal level: never had any symptoms (category 0), had symptoms but they have resolved (category 1), had symptoms with weak problems (category 2), had symptoms with moderate problems (category 3), and had symptoms with severe problems (category 4). In this study, the total RPQ score was calculated as the sum of scores for each of the 16 events. Scores could range from 0, if the patients never had any symptoms (category 0) to 64 if the subjects had problems in all 16 elements of category 4.

2.3. SWI parameters and processing

All MR imaging was performed at 3.0 T (MRI Siemens Tim Trio system, Siemens Medical Systems, Erlangen, Germany) using an 8-channel phased-array coil. Earplugs were used to reduce noise during the MR scanning and foam pads were applied to keep the head stationary. To ease the effects of postural changes, all subjects lied in a dorsal position for at least 30 min before the MRI scanning under peaceful circumstances. All transverse images were obtained parallel to the anterior-posterior commissural line on the middle sagittal plane and included the whole cerebral parenchyma. Conventional axial T1WI and T2 FLAIR were collected to exclude subjects with other brain structural abnormalities and congenital diseases. Then a high resolution 3D flow-compensated SWI sequence was used and both magnitude and phase images were reconstructed. The imaging parameters of the T1WI sequence were: TR/TE = 250/2.46 ms; number of slices = 21; voxel resolution = 0.9 × 0.8 × 5 mm3; field of view = 240 × 100 mm; receiver bandwidth = 330 Hz/pixel; flip angle = 70°; 1 acquisition; total acquisition time = 66 s. The imaging parameters of the T2 FLAIR sequence were: TR/TE = 9290/93 ms; TI = 2500 ms; number of slices = 25; voxel resolution = 0.9 × 0.9 × 4.0 mm3; field of view = 220 × 90.6 mm; slice thickness = 4.0 mm; receiver bandwidth = 287 Hz/pixel; flip angle = 130°; 1 acquisition; averages 1; total acquisition time = 169 s. The imaging parameters of the DWI sequence were: TR/TE = 5500/130 ms; b = 0/1000; number of slices = 20; voxel resolution = 1.8 × 1.8 × 5.0 mm3; field of view = 240 × 100 mm; slice thickness = 5.0 mm; receiver bandwidth = 968 Hz/pixel; EPI factor = 136; 1 acquisition and total acquisition time = 40 s. The imaging parameters of the SWI sequence were: TR/TE = 27/20 ms; voxel size = 0.5 × 0.5 × 2 mm3; field of view = 230 × 200 mm2; receiver bandwidth = 120 Hz/pixel; 1 acquisition; flip angle = 15°; number of slices = 56; and acquisition time = 179 s. The total acquisition time of T1, T2 FLAIR, DWI and SWI was under 8 min (454 s).

The QSM images were reconstructed using SMART (Susceptibility Mapping and Phase Artifacts Removal Toolbox, Detroit, Michigan, USA) post-processing software (Haacke et al., 2010, Haacke et al., 2015) and included the following steps: first, the unwanted low signal regions outside the brain were eliminated using Brain Extraction Tool (BET) in FMRIB Software Library (FSL) (Smith, 2002); the background phase was reduced using a 96 × 96 homodyne high-pass filter (due to the retrospective nature of this study, the raw unfiltered phase images were not available and the phase images obtained using the SWI sequence were already processed by a 96 × 96 homodyne high-pass filter, and hence, no additional filtering was applied during post-processing); finally, QSM data were generated using truncated k-space division with a regularization threshold of 0.1 (Haacke et al., 2010, Haacke et al., 2015). These post-processing steps led to a high resolution QSM showing the cerebral venous structures clearly.

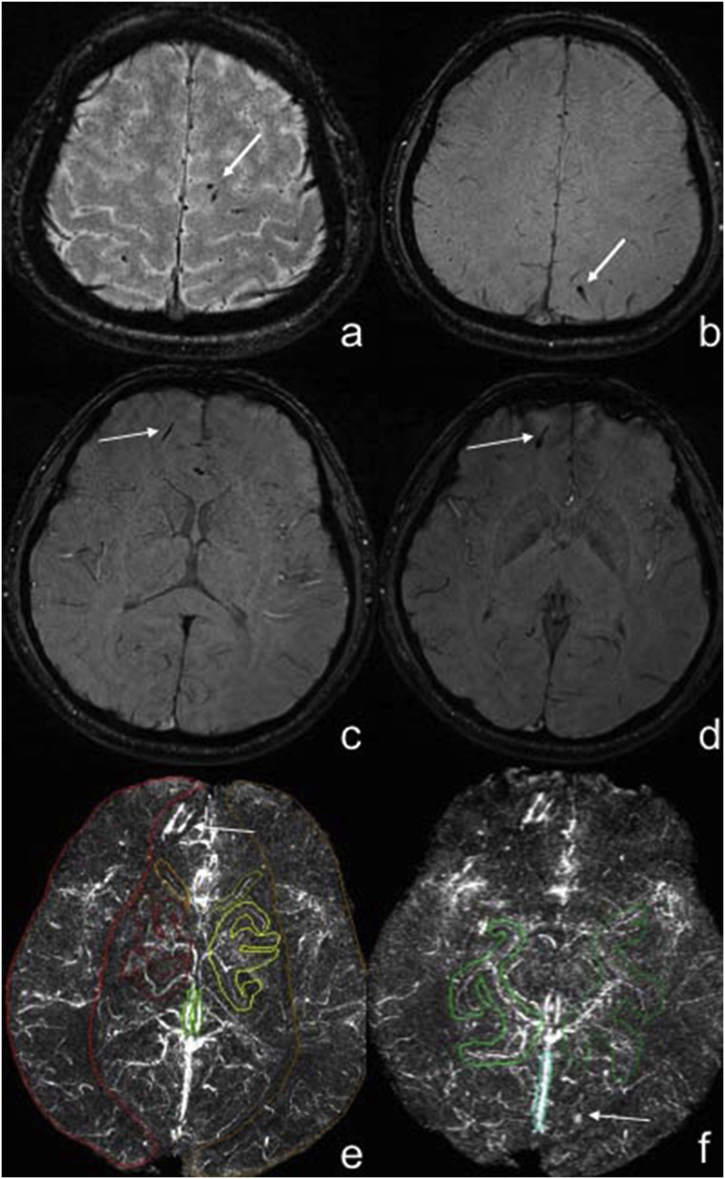

The analysis of the QSM data was performed with SPIN (signal processing in nuclear magnetic resonance, Detroit, Michigan, USA) software. The susceptibility of major cerebral veins was measured on the maximum intensity projection (MIP) over 16 slices. To include major veins and eliminate the artifacts from the sinus cavities, the coverage extended from the highest level of the cerebrum to the lowest level of the cerebellum. Volumes of interests (VOIs) of major veins were outlined manually on the consecutive slices of MIP QSM images, which showed the cerebral veins clearly. VOIs of major veins were delineated according to the normal anatomic structures and distribution regions of cerebral major veins and the susceptibility of cerebral veins were measured by two neuroradiologists, respectively (C.Z. with five years of experience in neuroradiology; C.C. with eight years of experience in neuroradiology), who was blinded to the epidemiological and clinical information of all the participants. The major cerebral veins included the right and left cortical veins, septal veins, thalamostriate veins, internal cerebral veins, the basal veins and straight sinus. Consecutive slices were drawn to cover the body of major veins except for the topmost and lowermost levels of cerebral veins, to avoid the partial volume effect. The VOIs of cortical veins were drawn to include the whole cerebral hemisphere. The VOIs of other cerebral veins were drawn close to the cerebral veins as much as possible and cover the whole distribution regions of cerebral veins (Fig. 1). Before the measurement of venous susceptibility, a threshold of 90 parts per billion (ppb) was used to set the susceptibility of brain tissues surrounding the cerebral veins in the VOIs to 0, to avoid their influence on the measurement of susceptibility of cerebral major veins in the VOIs. Cerebral microbleeds and other small vessels were also avoided when drawing the major veins. Mean and standard deviation of the susceptibility in regional cerebral veins were recorded.

Fig. 1.

Measurement of the susceptibility value of major cerebral veins in mTBI patients using maximum-intensity projection quantitative susceptibility mapping.

Panels a–d. Male, 25 years old, struck by vehicle, some dot-like, strip-like low signal was shown in the subcortex of bilateral parietal lobes, right frontal lobe in the SWI images, which was diagnosed as axonal injury (white arrows). Panels e–f showed the high signal of cerebral veins in maximum-intensity projection (MIP) QSM (the slab thickness of MIP QSM was 16 mm) and the volume of interests of cerebral veins for the measurement of susceptibility value in MIP QSM images. The axonal injury lesions showed high signal (white arrows).

2.4. Statistical analysis

The statistical evaluation of data was performed using SPSS 19.0 (SPSS Inc. Chicago, Ill., USA) software. In order to explore the reproducibility of the QSM method, the agreement between the susceptibility of cerebral veins from the HCs in our study and that from normal people studied by Doshi et al. (2015) was calculated using Pearson's correlation and inter-class correlation (ICC) was also calculated in mTBI patients and HCs. The normal distribution of data was explored by the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. The difference of age and gender among three groups was explored using ANOVA and the Chi-square test. Due to the non-normal distribution of the susceptibility of left septal vein in HCs, the difference in susceptibility of cerebral veins among three groups was evaluated using non-parametric test. Similarly, due to the non-normal distribution of ETPT of non-AI patients, the difference in the ETPT and RPQ scores between AI and non-AI group was explored using the Mann-Whitney U test and the two independent sample t-test, respectively. The correlations between the susceptibility of cerebral veins in the non-AI group and RPQ scores, between the susceptibility of cerebral veins in the AI group and either ETPT or RPQ scores were calculated using Pearson's correlation analysis. The correlations between the susceptibility of cerebral veins in non-AI group and ETPT were calculated using Spearman's correlation analysis. The diagnostic efficiency of susceptibility to discriminate mTBI patients and HCs was evaluated using the receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC). For the multiple comparison of susceptibility in cerebral major veins among non-AI patients, AI-patients and HCs, a Bonferroni-corrected P < 0.0045 (0.05/11) was considered as significant. The false discovery rate (FDR) correction was applied for the correlations between the susceptibility of cerebral veins from the HCs in our study and that from normal people studied by Doshi et al.; the correlations between the susceptibility of cerebral veins in AI and non-AI group and either ETPT or RPQ scores, an FDR-corrected P < 0.05 was considered significant.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic and clinical characteristic of subjects

The difference in demographic and RPQ scores, etiologies of the AI and non-AI patients and HCs are shown in Table 1. There was no significant difference in age and gender among the three groups (P = 0.172, P = 0.848, respectively). The mean ETPT in the AI and non-AI group was 110.13 ± 105.93 h and 51.03 ± 39.26 h, respectively, while there was no significant difference in the ETPT between the two mTBI groups (P = 0.071). No significant difference in RPQ scores between the AI (9.06 ± 5.58) and non-AI (10.06 ± 6.69) group was found (P = 0.588).

Table 1.

The difference in demographic and post-concussive symptom scores among non-AI patients, AI patients and HCs.

| Clinical parameters | Non-AI patients (n = 32) | AI patients (n = 16) | HCs (n = 32) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (year) | 37.03 ± 10.65 | 32.06 ± 10.00 | 37.78 ± 9.81 | 0.172a |

| Gender (male/female) | 22/10 | 10/6 | 20/12 | 0.848^ |

| ETPT (h) | 51.03 ± 39.26 | 110.13 ± 105.93 | – | 0.071b |

| RPQ scores | 10.06 ± 6.69 | 9.06 ± 5.58 | – | 0.588& |

| The etiologies of patients with mTBI (n = 48) | ||||

| Assault (n = 15) | 9 | 6 | – | – |

| Struck by vehicle (n = 24) | 19 | 5 | – | – |

| Falling (n = 6) | 3 | 3 | – | – |

| Blunt trauma from falling objects (n = 2) | 1 | 1 | – | – |

| Blast injury (n = 1) | 0 | 1 | – | – |

mTBI = mild traumatic brain injury, AI = axonal injury, RPQ = Rivermead Post-Concussion Symptoms Questionnaire.

The difference of age among the three groups (non-AI group, AI group and healthy control group) was explored using a one-way analysis of variance.

The difference in ETPT between non-AI group and AI group was explored using Mann-Whitney U test.

The difference of gender among three groups (non-AI group, AI group and healthy control group) was explored using the Chi-square test.

The difference in RPQ scores between non-AI and AI groups was explored using the two independent sample t-test.

3.2. Reproducibility of the QSM method

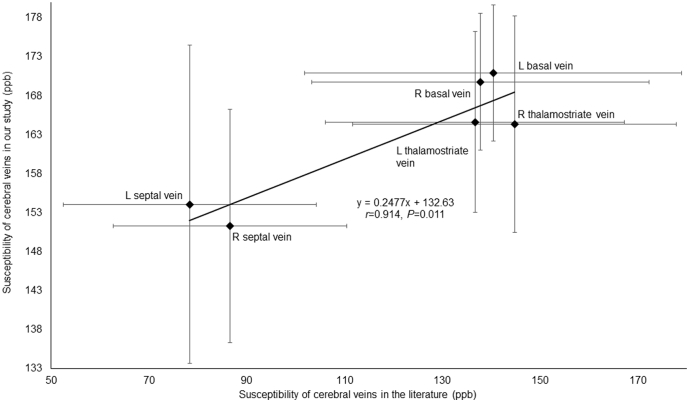

In order to explore the reproducibility of the QSM method, we compared our results to those reported in Doshi et al. (2015). We found the susceptibility of major cerebral veins from the HCs in our study was highly consistent with that from normal controls reported in their study (Pearson's correlation; r = 0.914, P = 0.011; FDR corrected) (Fig. 2). We also calculated the ICC in mTBI patients and HCs between two measurements. The ICC values for right cerebral cortical vein, left cerebral cortical vein, right thalamostriate vein, left thalamostriate vein, right septal vein, left septal vein, right internal cerebral vein, left internal cerebral vein, right basal vein, left basal vein and straight sinus in mTBI patients were 0.97, 0.98, 0.98, 0.97, 0.99, 0.99, 0.99, 0.99, 0.95, 0.96, 0.99, respectively and the ICC values for above these veins in HCs were 0.96, 0.95, 0.97, 0.96, 0.98, 0.99, 0.99, 0.99, 0.98, 0.98, 0.99, respectively, demonstrating good reproducibility of the analysis method.

Fig. 2.

The correlation between susceptibility of cerebral veins in our study and that in the Doshi et al.'s study.

The susceptibility of each major cerebral vein including left septal vein, right septal vein, left thelamostriate vein, right thalamostriate vein, left basal vein and right basal vein from HCs measured in our study were highly consistent with the measured susceptibility values from normal controls reported by the study of Doshi et al.'s by Pearson's correlation (r = 0.914, P = 0.011, FDR corrected) (the error bars represent standard deviation of measured susceptibility of cerebral veins).

3.3. Analyses of the susceptibility among the three groups

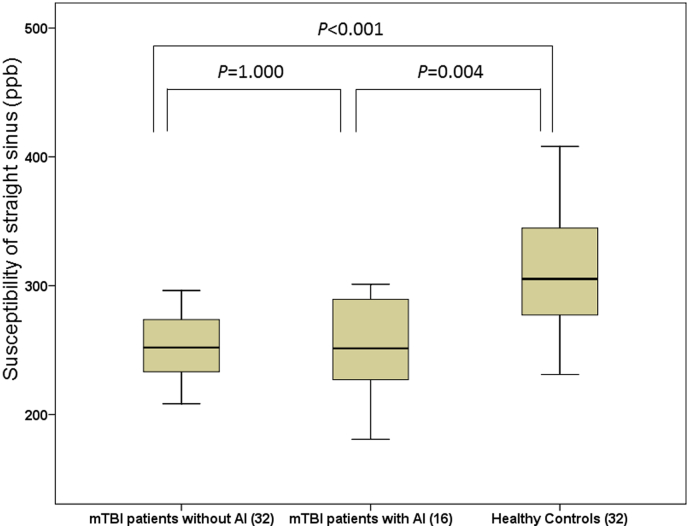

The comparison of susceptibility of major cerebral veins among the three groups using non-parametric test is presented in Table 2. There was a significant difference in the susceptibility of the straight sinus among the three groups (P < 0.001, Bonferroni corrected). Specifically, the susceptibility of the straight sinus in non-AI (256 ± 35, P < 0.001, Bonferroni corrected) and AI (265 ± 61, P = 0.004, Bonferroni corrected) group was significantly lower than that in the healthy control group (311 ± 43) (Fig. 3). But there was no significant difference in the susceptibility of straight sinus between the two mTBI groups (P = 1.000).

Table 2.

The difference in susceptibility (ppb) of each cerebral vein among non-AI, AI patients and HCs.

| Cerebral veins | Non-AI patients (n = 32) | AI patients (n = 16) | HCs (n = 32) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Right cortical vein | 164.782 ± 8.55 | 160.768 ± 7.78 | 163.057 ± 7.39 | 0.257 |

| Left cortical vein | 165.496 ± 10.09 | 162.911 ± 13.11 | 160.367 ± 8.10 | 0.131 |

| Right thalamostriate vein | 163.104 ± 13.01 | 164.702 ± 13.16 | 164.374 ± 13.87 | 0.900 |

| Left thalamostriate vein | 161.797 ± 12.35 | 159.770 ± 13.09 | 164.650 ± 11.60 | 0.391 |

| Right septal vein | 151.096 ± 15.09 | 146.878 ± 22.27 | 151.327 ± 14.98 | 0.65 |

| Left septal vein | 151.199 ± 12.59 | 157.667 ± 37.23 | 154.088 ± 20.42 | 0.636 |

| Right cerebral internal vein | 199.521 ± 28.39 | 195.364 ± 36.10 | 189.564 ± 28.45 | 0.418 |

| Left cerebral internal vein | 199.775 ± 31.45 | 195.383 ± 28.24 | 196.410 ± 26.03 | 0.847 |

| Right basal vein | 165.936 ± 7.42 | 170.132 ± 8.99 | 169.794 ± 8.78 | 0.117 |

| Left basal vein | 169.614 ± 10.93 | 165.559 ± 8.16 | 170.977 ± 8.73 | 0.185 |

| Straight sinus | 255.514 ± 35.25 | 264.840 ± 60.80 | 310.634 ± 43.05 | < 0.001a |

Stand for P < 0.0045, Bonferroni corrected.

Fig. 3.

The difference in susceptibility of straight sinus among AI patients, non-AI patients and healthy controls.

The susceptibility of straight sinus in non-AI group (256 ± 35) was significantly lower than that in healthy control group (311 ± 43) (P < 0.001, Bonferroni corrected), the susceptibility of straight sinus in AI group (265 ± 61) was significantly lower than that in healthy control group (311 ± 43) (P = 0.004, Bonferroni corrected). But there was no significant difference in susceptibility of straight sinus between non-AI group (256 ± 35) and AI group (265 ± 61) (P = 1.000).

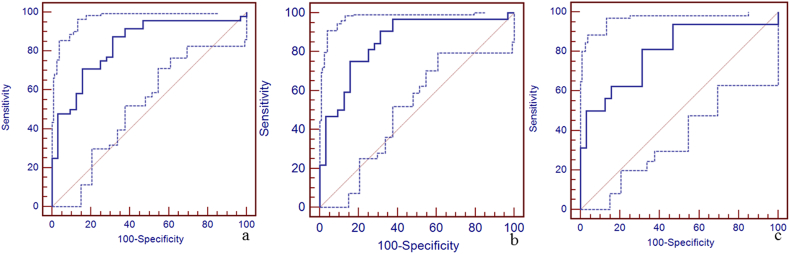

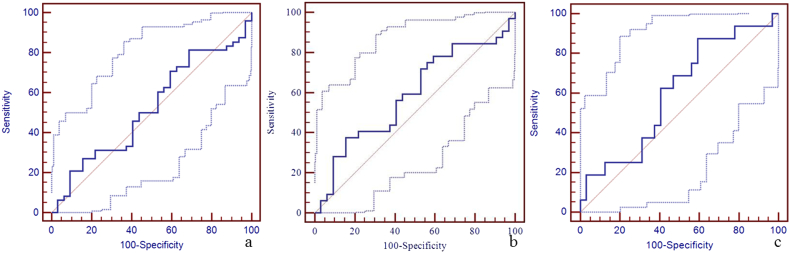

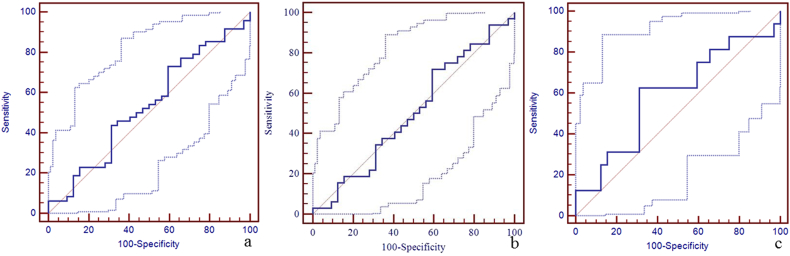

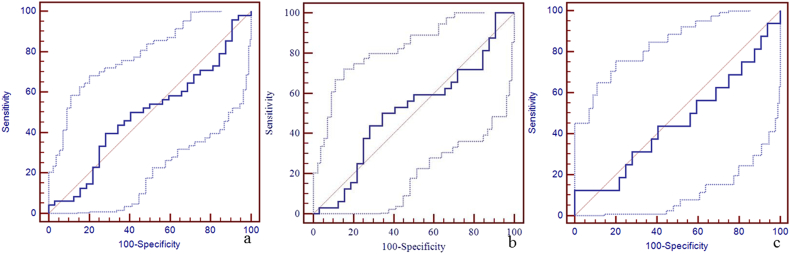

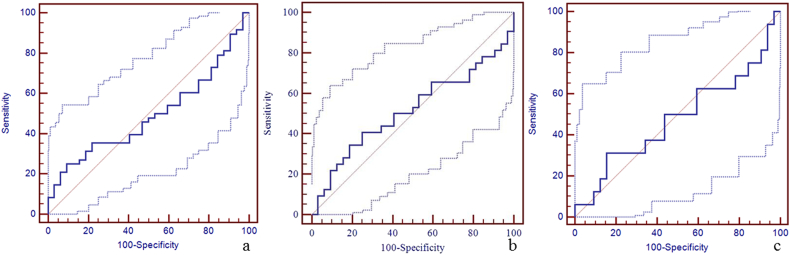

3.4. Diagnostic efficiency of susceptibility of straight sinus for discrimination between patients and HCs

Due to a significant difference in the susceptibility of the straight sinus among the three groups, the sensitivity, specificity, and area under the curve (AUC) of susceptibility of the straight sinus for the discrimination between mTBI patients, non-AI patients, AI patients and HCs using the receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC) are shown in Fig. 4. The best cut-off value for the discrimination between mTBI patients and HCs was 298 ppb with a sensitivity of 88% (95% CI: 75–95), specificity 69% (95% CI: 50–84), and AUC value 0.84 (95% CI: 0.74–0.91) (Fig. 4a). The best cut-off value for the discrimination between non-AI patients and HCs was 273 ppb with the sensitivity 75% (95% CI: 57–89), specificity 84% (95% CI: 67–95), and AUC value 0.86 (95% CI: 0.75–0.93) (Fig. 4b). The best cut-off value for the discrimination between AI patients and HCs was 290 ppb with sensitivity 81% (95% CI: 54–96), specificity 69% (95% CI: 50–84), and AUC of 0.80 (95% CI: 0.66–0.90) (Fig. 4c). We also calculated the sensitivity, specificity, and AUC of susceptibility of the other veins for the discrimination between mTBI patients, non-AI patients, AI patients and HCs using the ROC (Supplementary Table 1, Supplementary Fig. 1, Supplementary Fig. 2, Supplementary Fig. 3, Supplementary Fig. 4, Supplementary Fig. 5, Supplementary Fig. 6, Supplementary Fig. 7, Supplementary Fig. 8, Supplementary Fig. 9, Supplementary Fig. 10).

Fig. 4.

The diagnostic efficiency of susceptibility of straight sinus for the discrimination between mTBI patients, non-AI patients, AI patients and HCs using the receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC).

Panel a. The best cut-off susceptibility of straight sinus for the discrimination between mTBI patients and HCs was 298 ppb with the sensitivity (88%, 95% CI: 75–95), specificity (69%, 95% CI: 50–84), and AUC value (0.84, 95% CI: 0.74–0.91). Panel b. The best cut-off value for the discrimination between non-AI patients and HCs was 273 ppb with the sensitivity (75%, 95% CI: 57–89), specificity (84%, 95% CI: 67–95), and AUC value (0.86, 95% CI: 0.75–0.93). Panel c. The best cut-off value for the discrimination between AI patients and HCs was 290 ppb with the sensitivity (81%, 95% CI: 54–96), specificity (69%, 95% CI: 50–84), and AUC value (0.80, 95% CI: 0.66–0.90).

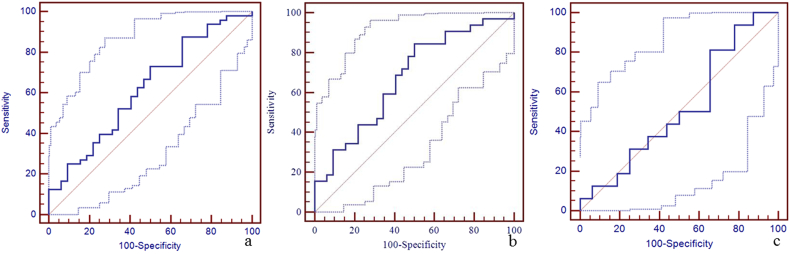

Supplementary Fig. 1.

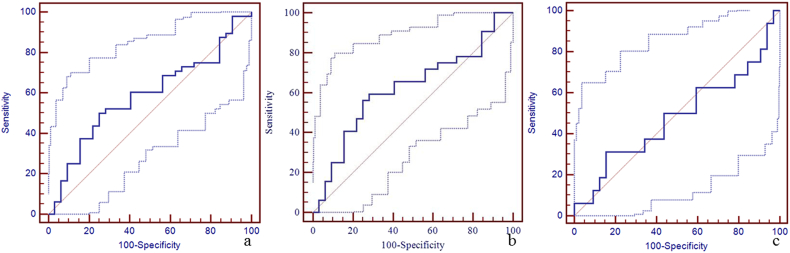

The diagnostic efficiency of susceptibility of right cerebral cortical vein for the discrimination between mTBI patients, non-AI patients, AI patients and HCs using ROC.

The best cut-off susceptibility of right cerebral cortical vein for the discrimination between mTBI patients and HCs was 158 ppb with a sensitivity of 81% (95% CI: 67–91), specificity 31% (95% CI: 16–50), and AUC value 0.52 (95% CI: 0.41–0.64) (panel a). The best cut-off susceptibility of right cerebral cortical vein for the discrimination between non-AI patients and HCs was 168 ppb with the sensitivity 38% (95% CI: 21–56), specificity 84% (95% CI: 67–95), and AUC value 0.59 (95% CI: 0.46–0.71) (panel b). The best cut-off susceptibility of right cerebral cortical vein for the discrimination between AI patients and HCs was 166 ppb with sensitivity 88% (95% CI: 62–98), specificity 41% (95% CI: 24–59), and AUC of 0.60 (95% CI: 0.45–0.74) (panel c).

Supplementary Fig. 2.

The diagnostic efficiency of susceptibility of left cerebral cortical vein for the discrimination between mTBI patients, non-AI patients, AI patients and HCs using ROC.

The best cut-off susceptibility of left cerebral cortical vein for the discrimination between mTBI patients and HCs was 159 ppb with a sensitivity of 73% (95% CI: 58–85), specificity 50% (95% CI: 32–68), and AUC value 0.62 (95% CI: 0.51–0.73) (panel a). The best cut-off susceptibility of left cerebral cortical vein for the discrimination between non-AI patients and HCs was 159 ppb with the sensitivity 84% (95% CI: 67–95), specificity 50% (95% CI: 32–68), and AUC value 0.67 (95% CI: 0.54–0.79) (panel b). The best cut-off susceptibility of left cerebral cortical vein for the discrimination between AI patients and HCs was 153 ppb with sensitivity 94% (95% CI: 70–100), specificity 22% (95% CI: 9–40), and AUC of 0.52 (95% CI: 0.37–0.66) (panel c).

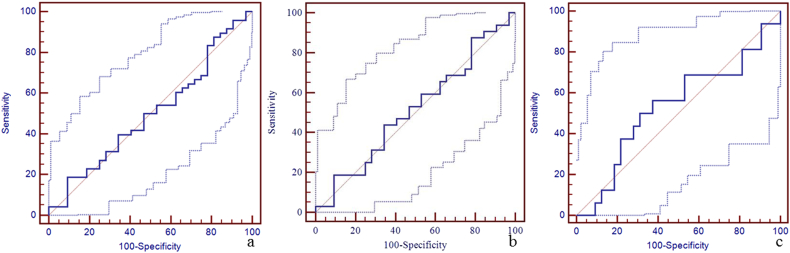

Supplementary Fig. 3.

The diagnostic efficiency of susceptibility of right thalamostriate vein for the discrimination between mTBI patients, non-AI patients, AI patients and HCs using ROC.

The best cut-off susceptibility of right thalamostriate vein for the discrimination between mTBI patients and HCs was 150 ppb with a sensitivity of 19% (95% CI: 9–33), specificity 91% (95% CI: 75–98), and AUC value 0.50 (95% CI: 0.39–0.61) (panel a). The best cut-off susceptibility of right thalamostriate vein for the discrimination between non-AI patients and HCs was 150 ppb with the sensitivity 19% (95% CI: 7–36), specificity 91% (95% CI: 75–98), and AUC value 0.51 (95% CI: 0.39–0.64) (panel b). The best cut-off susceptibility of right thalamostriate vein for the discrimination between AI patients and HCs was 167 ppb with sensitivity 56% (95% CI: 30–80), specificity 63% (95% CI: 44–79), and AUC of 0.53 (95% CI: 0.38–0.68) (panel c).

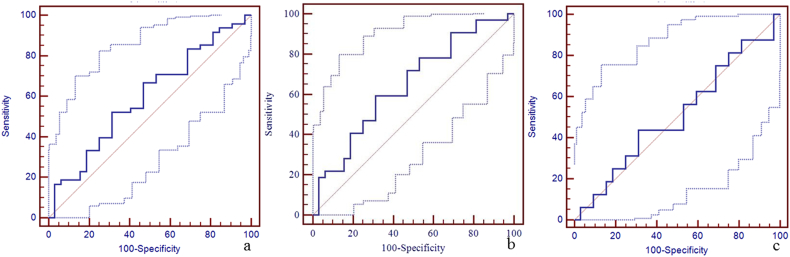

Supplementary Fig. 4.

The diagnostic efficiency of susceptibility of left thalamostriate vein for the discrimination between mTBI patients, non-AI patients, AI patients and HCs using ROC.

The best cut-off susceptibility of left thalamostriate vein for the discrimination between mTBI patients and HCs was 150 ppb with a sensitivity of 25% (95% CI: 14–40), specificity 97% (95% CI: 84–100), and AUC value 0.59 (95% CI: 0.48–0.70) (panel a). The best cut-off susceptibility of left thalamostriate vein for the discrimination between non-AI patients and HCs was 150 ppb with the sensitivity 25% (95% CI: 12–43), specificity 97% (95% CI: 84–100), and AUC value 0.59 (95% CI: 0.46–0.71) (panel b). The best cut-off susceptibility of left thalamostriate vein for the discrimination between AI patients and HCs was 150 ppb with sensitivity 25% (95% CI: 7–52), specificity 97% (95% CI: 84–100), and AUC of 0.59 (95% CI: 0.44–0.73) (panel c).

Supplementary Fig. 5.

The diagnostic efficiency of susceptibility of right septal vein for the discrimination between mTBI patients, non-AI patients, AI patients and HCs using ROC.

The best cut-off susceptibility of right septal vein for the discrimination between mTBI patients and HCs was 153 ppb with a sensitivity of 73% (95% CI: 58–85), specificity 41% (95% CI: 24–59), and AUC value 0.53 (95% CI: 0.42–0.65) (panel a). The best cut-off susceptibility of right septal vein for the discrimination between non-AI patients and HCs was 153 ppb with the sensitivity 72% (95% CI: 53–86), specificity 41% (95% CI: 24–59), and AUC value 0.50 (95% CI: 0.38–0.63) (panel b). The best cut-off susceptibility of right septal vein for the discrimination between AI patients and HCs was 146 ppb with sensitivity 63% (95% CI: 35–85), specificity 69% (95% CI: 50–84), and AUC of 0.59 (95% CI: 0.44–0.73) (panel c).

Supplementary Fig. 6.

The diagnostic efficiency of susceptibility of left septal vein for the discrimination between mTBI patients, non-AI patients, AI patients and HCs using ROC.

The best cut-off susceptibility of left septal vein for the discrimination between mTBI patients and HCs was 146 ppb with a sensitivity of 40% (95% CI: 26–55), specificity 72% (95% CI: 53–86), and AUC value 0.49 (95% CI: 0.38–0.61) (panel a). The best cut-off susceptibility of left septal vein for the discrimination between non-AI patients and HCs was 145 ppb with the sensitivity 44% (95% CI: 26–62), specificity 72% (95% CI: 53–86), and AUC value 0.51 (95% CI: 0.38–0.64) (panel b). The best cut-off susceptibility of left septal vein for the discrimination between AI patients and HCs was 129 ppb with sensitivity 13% (95% CI: 2–38), specificity 100% (95% CI: 89–100), and AUC of 0.46 (95% CI: 0.31–0.61) (panel c).

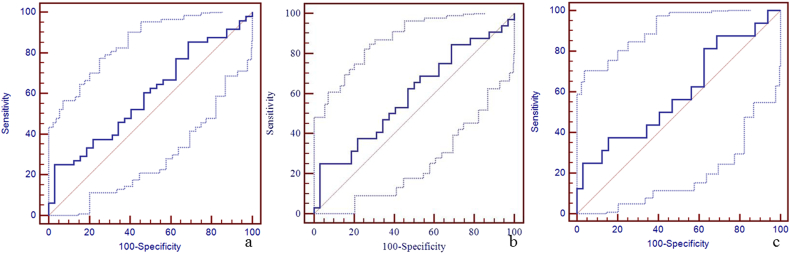

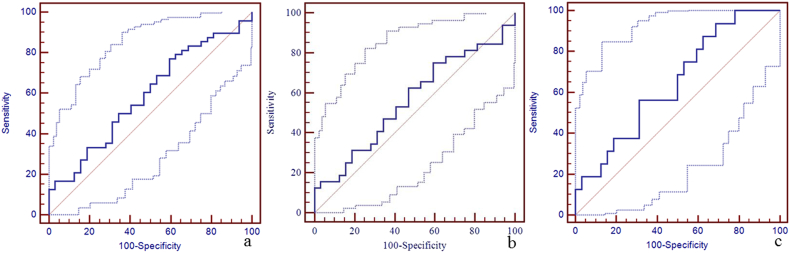

Supplementary Fig. 7.

The diagnostic efficiency of susceptibility of right cerebral internal vein for the discrimination between mTBI patients, non-AI patients, AI patients and HCs using ROC.

The best cut-off susceptibility of right cerebral internal vein for the discrimination between mTBI patients and HCs was 195 ppb with a sensitivity of 50% (95% CI: 35–65), specificity 75% (95% CI: 57–89), and AUC value 0.59 (95% CI: 0.47–0.70) (panel a). The best cut-off susceptibility of right cerebral internal vein for the discrimination between non-AI patients and HCs was 193 ppb with the sensitivity 59% (95% CI: 41–73), specificity 72% (95% CI: 53–86), and AUC value 0.62 (95% CI: 0.49–0.74) (panel b). The best cut-off susceptibility of right cerebral internal vein for the discrimination between AI patients and HCs was 169 ppb with sensitivity 31% (95% CI: 11–59), specificity 84% (95% CI: 67–95), and AUC of 0.48 (95% CI: 0.33–0.63) (panel c).

Supplementary Fig. 8.

The diagnostic efficiency of susceptibility of left cerebral internal vein for the discrimination between mTBI patients, non-AI patients, AI patients and HCs using ROC.

The best cut-off susceptibility of left cerebral internal vein for the discrimination between mTBI patients and HCs was 174 ppb with a sensitivity of 25% (95% CI: 14–40), specificity 91% (95% CI: 75–98), and AUC value 0.49 (95% CI: 0.38–0.61) (panel a). The best cut-off susceptibility of left cerebral internal vein for the discrimination between non-AI patients and HCs was 202 ppb with the sensitivity 41% (95% CI: 24–59), specificity 75% (95% CI: 57–89), and AUC value 0.52 (95% CI: 0.39–0.64) (panel b). The best cut-off susceptibility of left cerebral internal vein for the discrimination between AI patients and HCs was 174 ppb with sensitivity 31% (95% CI: 11–59), specificity 91% (95% CI: 75–98), and AUC of 0.51 (95% CI: 0.36–0.66) (panel c).

Supplementary Fig. 9.

The diagnostic efficiency of susceptibility of right basal vein for the discrimination between mTBI patients, non-AI patients, AI patients and HCs using ROC.

The best cut-off susceptibility of right basal vein for the discrimination between mTBI patients and HCs was 166 ppb with a sensitivity of 52% (95% CI: 37–67), specificity 69% (95% CI: 50–84), and AUC value 0.59 (95% CI: 0.48–0.70) (panel a). The best cut-off susceptibility of right basal vein for the discrimination between non-AI patients and HCs was 166 ppb with the sensitivity 59% (95% CI: 41–76), specificity 69% (95% CI: 50–84), and AUC value 0.65 (95% CI: 0.52–0.76) (panel b). The best cut-off susceptibility of right basal vein for the discrimination between AI patients and HCs was 172 ppb with sensitivity 44% (95% CI: 20–70), specificity 69% (95% CI: 50–84), and AUC of 0.51 (95% CI: 0.36–0.66) (panel c).

Supplementary Fig. 10.

The diagnostic efficiency of susceptibility of left basal vein for the discrimination between mTBI patients, non-AI patients, AI patients and HCs using ROC.

The best cut-off susceptibility of left basal vein for the discrimination between mTBI patients and HCs was 172 ppb with a sensitivity of 77% (95% CI: 63–88), specificity 41% (95% CI: 24–59), and AUC value 0.59 (95% CI: 0.48–0.70) (panel a). The best cut-off susceptibility of left basal vein for the discrimination between non-AI patients and HCs was 169 ppb with the sensitivity 63% (95% CI: 44–79), specificity 53% (95% CI: 35–71), and AUC value 0.56 (95% CI: 0.43–0.69) (panel b). The best cut-off susceptibility of left basal vein for the discrimination between AI patients and HCs was 166 ppb with sensitivity 56% (95% CI: 30–80), specificity 69% (95% CI: 50–84), and AUC of 0.65 (95% CI: 0.50–0.78) (panel c).

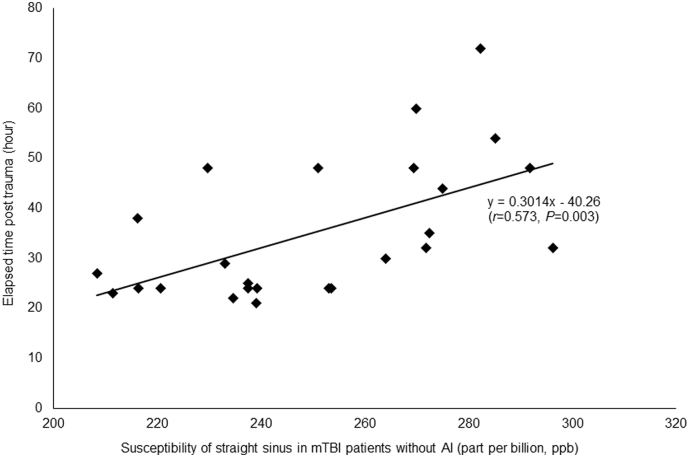

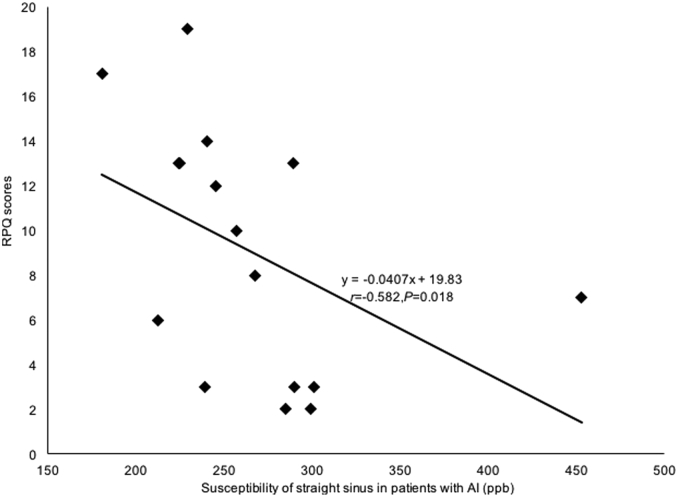

3.5. Correlation analyses with ETPT and post-concussive symptom scores

In the non-AI group, a positive correlation between the susceptibility of the straight sinus and the ETPT was observed (r = 0.573, P = 0.003, FDR corrected), as shown in Fig. 5. No significant correlation was found in the AI group (P = 0.992, FDR corrected). On the other hand, in the AI group, a negative correlation between the susceptibility of the straight sinus and the RPQ scores was observed (r = − 0.582, P = 0.018, FDR corrected), as shown in Fig. 6, but no significant correlation was found in the non-AI group (P = 0.886, FDR corrected). There were no correlations between the susceptibility of other cerebral veins (the right and left cortical veins; septal veins; thalamostriate veins; internal cerebral veins; basal veins) and ETPT or RPQ scores in the AI or the non-AI groups (P > 0.05).

Fig. 5.

The correlation between susceptibility of straight sinus in non-AI patients and ETPT.

In the non-AI group, the susceptibility of straight sinus significantly positively correlated with the ETPT (r = 0.573, P = 0.003, FDR corrected). Our result found that with the ETPT increased, the susceptibility of straight sinus in non-AI patients was increased, suggesting that the increased regional cerebral SvO2 tended to return back to normal levels.

Fig. 6.

The correlation between susceptibility of straight sinus in AI patients and RPQ scores.

In the AI group, the susceptibility of straight sinus significantly negatively correlated with the RPQ scores (r = − 0.582, P = 0.018, FDR corrected). Our result indicated that the decreased susceptibility of straight sinus (increased regional cerebral SvO2) could indicate severe post-concussive symptoms.

4. Discussion

There were three important findings in our study. First, the susceptibility of the straight sinus in non-AI and AI patients was significantly lower than that in HCs indicating an increased regional cerebral SvO2 in patients after mTBI. The best cut-off values for the discrimination between mTBI patients, non-AI patients, AI patients and HCs were 298 ppb, 273 ppb and 290 ppb. Second, as the ETPT increased, the susceptibility of straight sinus in non-AI patients was increased, indicating that the regional cerebral SvO2 tended to decrease to normal levels. Third, the RPQ scores increased with the decreasing susceptibility of the straight sinus, suggesting an increase in cerebral SvO2 due to severe post-concussive symptoms. The lower relative susceptibility in the straight sinus suggesting a higher level of oxygenated blood is consistent with the findings in Doshi et al. (2015). In that study, the differences between the subgroups (non-AI patient group and AI patient group) of mTBI patients are not considered. However, the abnormalities such as moderate bleeds, small bleed, nonspecific hyperintensities, arachnoid cyst, and pericallosal lipoma in the mTBI patients of Doshi et al.'s study may affect the susceptibility of the veins. In addition, the healthy controls (HCs) in their study had some abnormalities, such as capillary telangiectasia, pineal gland cyst, and nonspecific hyperintensity, which may also affect their results. Besides, the sample size of their study was relatively small (14 patients). These may explain the difference between the findings obtained in our study and Doshi et al.'s study. Nonetheless, the susceptibility of cerebral veins of HCs measured in our study are in good agreement with those reported by Doshi et al. (2015), indicating good reproducibility for using QSM to evaluate the cerebral SvO2.

One reason for lower relative susceptibility may be from a decrease in cerebral metabolic rate of oxygen consumption in mTBI patients, which has been suggested in some earlier papers (Chen et al., 2004, Harris et al., 2012, Hovda et al., 1991). During the acute and sub-acute stages, the cerebral tissues might use another energy source, such as lactate, instead of glucose in some extreme conditions including trauma and starvation (Prins et al., 2004). One possible mechanism is mitochondrial dysfunction post TBI leading to a lower oxygen consumption.

In our study, we only found significant difference in the susceptibility of the straight sinus among three groups. There are a few possible reasons for this. First, the size of straight sinus was larger than that of the other cerebral veins and the susceptibility quantification of the other cerebral veins may be affected by partial volume effects because of the limited resolution in the through-plane direction. Hence, it was easier to highlight the significant susceptibility difference due to the reduced partial volume effects. In addition, the partial volume effects are also dependent on the orientation of the vessel. However, for veins in similar orientations, the estimate of the relative change in susceptibilities of these veins should not be affected much, as similar level of underestimations in susceptibilities are caused by partial volume effects. Nonetheless, in McDaniel et al. (2017), a promising technique was proposed, in which the partial volume effects can be compensated through a joint reconstruction using both magnitude and phase images for vessels in certain orientations. This method provides more accurate estimation of the oxygen saturation of the veins. Second, the cerebral region drained by the straight sinus was larger than that drained by other small cerebral veins, and hence, the change of susceptibility due to abnormal metabolism may be more obvious. It has been reported that straight sinus mostly receives the deep cerebral venous system draining deep gray matter, the inferior sagittal sinus and some regions of the upper brainstem through the confluence of the inferior sagittal sinus and great vein of Galen (Jain et al., 2013, Krishnamurthy et al., 2014). The great vein of Galen receives bilateral cerebral internal, basal, thalamostriate and septal veins (Pearl et al., 2011). The straight sinus also drains the deep brain structures including thalami, cerebral nuclei, midbrain, pontine nuclei and parahippocampal gyri. These brain structures stand for more conserved parts of the brain and are responsible for basic activities to sustain life such as the consciousness, respiratory and cardiovascular systems (Jain et al., 2013). This may also explain the more significant changes of the susceptibility in the straight sinus than the other veins.

No significant difference in the susceptibility of the straight sinus between the AI and non-AI patient groups was observed in this study. This may be due to the different ETPT between AI and non-AI patients. Even though severe cerebral tissue damage could cause reduction in SvO2 with an accompanying decrease in arterial blood supply (Shen et al., 2007), the time at which this change is measured is critical. Since the ETPT for the non-AI group was 51 h and was much shorter than the 110 h in the AI group, the different imaging time points of this cross-sectional study may assess different stages of injury and recovery in each group, making a direct comparison of SvO2 challenging. This recovery is not unexpected (LosoiH et al., 2016). While the susceptibility of the straight sinus correlated with ETPT in the non-AI group, this was not observed in the AI group. This distinction may reflect the different pathological mechanisms in these two patient groups. The cerebral tissue damage in AI patients was more severe than that in non-AI patients (Cunningham et al., 2005, Martin et al., 1997). For the AI patients, the more extensive lesions in white matter tracts over widespread areas, such as brainstem, corpus callosum, basal ganglia and cerebral hemispheres, and the cerebral function may influence the rate of SvO2 recovery (Cunningham et al., 2005, Martin et al., 1997).

It is also found that the susceptibility of the straight sinus in AI patients negatively correlated with RPQ scores, which may indicate severe post-concussive symptoms. The RPQ is a commonly implemented neurophysiological test used to evaluate the severity of clinical symptoms after mild or moderate TBI (King et al., 1995). The RPQ has been considered as a unitary construct with no further demand to analyze its underlying structures (Potter et al., 2006) and has shown reliability and validity in the studies (King et al., 1999, King, 1996). The increased cerebral SvO2 may indicate reduced consumption of oxygen due to severe post-concussive symptoms which could be reflected by headache, dizziness, restlessness etc.

However, in non-AI patients, we did not find significant correlation between the susceptibility of straight sinus and RPQ scores, suggesting that the normal oxygen utilization is a key factor in maintaining brain function. There are a few possible reasons for this. First, the AI patients had more severe traumatic brain injury than the non-AI patients, which can cause obvious post-concussive symptoms. Second, the increased cerebral SvO2 of non-AI patients can return to the normal level with ETPT, indicating that the post-concussive symptoms can be alleviated in non-AI patients. Although we found no significant difference in RPQ scores between AI and non-AI group, the RPQ scores of non-AI patients were slightly higher (10.06 ± 6.69) than that of AI patients (9.06 ± 5.58).

There are a few limitations in our study. First, for generating QSM data, the background field removal was achieved by using homodyne high-pass filtering. It is known that high-pass filtering leads to under-estimation of the susceptibilities of structures with relatively low spatial frequency, such as the basal ganglia structures. This is the main reason of the reduction of the gray/white matter contrast in Fig. 1. Using more advanced background field removal algorithms such as Sophisticated Harmonic Artifact Reduction for Phase data (SHARP) (Schweser et al., 2011) and Projection onto Dipole Fields (PDF) (Liu et al., 2011), the accuracy of susceptibility quantification can be further improved. Second, the number of patients included in this study is relatively small. More patients, especially AI patients, should be evaluated to observe the difference in susceptibility, ETPT and RPQ scores. Third, our study design was cross-sectional. A longitudinal study should be performed to explore the change of relative susceptibility in cerebral major veins and the correlation between the relative susceptibility of cerebral major veins, ETPT and RPQ test. Fourth, we only measured the Hct in patient groups but not in healthy controls. Thus, the quantification and direct comparison of venous oxygen saturation between mTBI patients and HCs was not available. With Hct known, the venous oxygen saturation can be calculated using the following equation (Ahman et al., 2013):

where ∆ χdo is the difference in susceptibility per unit hematocrit between totally oxygenated blood and totally deoxygenated blood (∆ χdo = 4π × 0.27 ppm) (He and Yablonskiy, 2009, Jain et al., 2010). Hematocrit (Hct) is defined as fractional hematocrit value in the major draining veins, which is approximately 40% (Haacke et al., 1997). Yv is the cerebral SvO2 and ∆ χvein-tissue is the susceptibility of the cerebral veins. For the non-AI patients and AI patients, the cerebral SvO2 of straight sinus were calculated as 81.10 ± 2.8% and 79.58 ± 4.1%, respectively. Assuming Hct = 0.4 for female and Hct = 0.42 for male (Haacke et al., 1997, Fan et al., 2012, Jain et al., 2010), the cerebral SvO2 of straight sinus in HCs was estimated as 78.66 ± 3.5%. We found there were significant differences in cerebral SvO2 of straight sinus among the non-AI patients, AI patients and HCs using one-way ANOVA (P = 0.017, Bonferroni corrected). Especially for the non-AI patients, the cerebral SvO2 of straight sinus was significant higher than that in the HCs (P = 0.014, Bonferroni corrected). Finally, we did not measure cerebral perfusion. The increase in local perfusion may be another reason for increased cerebral SvO2. The increase in local perfusion may exceed the oxygen demand of the traumatic cerebral tissues, indicating the neuroprotective response following mTBI (Doshi et al., 2015). In the future, we will detect the changes of cerebral perfusion to decide whether the increased local perfusion was one reason for increased regional cerebral SvO2 in mTBI patients.

5. Conclusion

The decreased susceptibility of the straight sinus appears to correlate with post-concussive symptoms. In the case of the non-AI group, the decreased susceptibility of the straight sinus correlated with ETPT, indicating a recovery to normal levels of oxygenation over time. The susceptibility of the straight sinus provides an important biomarker for monitoring the progress of mild TBI and to differentiate mTBI patients from healthy controls.

The following are the supplementary data related to this article.

The sensitivity, specificity, and AUC of susceptibility of the cerebral veins for the discrimination between mTBI patients, non-AI patients, AI patients and HCs using ROC.

Funding

This work was supported by the Natural Scientific Foundation of China (grant number 81501457 to Shuang Xia) and the Tianjin Health Bureau of Science and Technology (grant number 14KG103 to Shuang Xia).

Conflicts of interest

The authors disclose no conflicts.

Acknowledgements

We appreciated Jiaxing Bao, who received her master of statistics from North Carolina State University in 2015, for her help in the statistics analysis. We appreciated the contributions of Dr. Chenguang Wan, MD to provide and evaluate the clinical data of mild traumatic brain injury patients.

Contributor Information

Shuang Xia, Email: xiashuang77@163.com.

Wen Shen, Email: shenwen66happy@163.com.

References

- Adams J.H., Doyle D., Ford I. Diffuse axonal injury in head injury: definition, diagnosis and grading. Histopathology. 1989;15:49–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.1989.tb03040.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahman S., Saveman B.I., Styrke J. Long-term follow-up of patients with mild traumatic brain injury: a mixed-method study. J. Rehabil. Med. 2013;45:758–764. doi: 10.2340/16501977-1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Congress of Rehabilitation Medicine Definition of mild traumatic brain injury. J. Head Trauma Rehabil. 1993;8:86–88. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes S.R., Haacke E.M. Susceptibility-weighted imaging: clinical angiographic applications. Magn. Reson. Imaging Clin. N. Am. 2009;17:47–61. doi: 10.1016/j.mric.2008.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buch S., Ye Y., Haacke E.M. Quantifying the changes in oxygen extraction fraction and cerebral activity caused by caffeine and acetazolamide. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2016 doi: 10.1177/0271678X16641129. (Epub ahead of print) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S.F., Richards H.K., Smielewski P. Relationship between flow-metabolism uncoupling and evolving axonal injury after experimental traumatic brain injury. J. Cereb. Blood Flow. Metab. 2004;24:1025–1036. doi: 10.1097/01.WCB.0000129415.34520.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham A.S., Salvador R., Coles J.P. Physiological thresholds for irreversible tissue damage in contusional regions following traumatic brain injury. Brain. 2005;128:1931–1942. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davceva N., Basheska N., Balazic J. Diffuse axonal injury-a distinct clinicopathological entity in closed head injuries. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 2015;36:127–133. doi: 10.1097/PAF.0000000000000168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies D.J., Su Z., Clancy M.T. Near-infrared spectroscopy in the monitoring of adult traumatic brain injury: a review. J. Neurotrauma. 2015 Jul 1;32(13):933–941. doi: 10.1089/neu.2014.3748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Kruijk J.R., Twijnstra A., Leffers P. Diagnostic criteria and differential diagnosis of mild traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj. 2001;15:99–106. doi: 10.1080/026990501458335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doshi H., Wiseman N., Liu J. Cerebral hemodynamic changes of mild traumatic brain injury at the acute stage. PLoS One. 2015;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0118061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan A.P., Benner T., Bolar D.S., Rosen B.R., Adalsteinsson E. Phase-based regional oxygen metabolism (PROM) using MRI. Magn. Reson. Med. 2012;67:669–678. doi: 10.1002/mrm.23050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan A.P., Bilgic B., Gagnon L. Quantitative oxygenation venography from MRI phase. Magn. Reson. Med. 2014;72:149–159. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faul M., Xu L., Wald M. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control; Atlanta (GA): 2010. Traumatic Brain Injury in the United States: Emergency Department Visits, Hospitalizations, and Deaths, 2002–2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari M., Mottola L., Quaresima V. Principles, techniques, and limitations of near infrared spectroscopy. Can. J. Appl. Physiol. 2004;29:463–487. doi: 10.1139/h04-031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haacke E.M., Lai S., Reichenbach J.R. In vivo measurement of blood oxygen saturation using magnetic resonance imaging: a direct validation of the blood oxygen level-dependent concept in functional brain imaging. Hum. Brain Mapp. 1997;5:341–346. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0193(1997)5:5<341::AID-HBM2>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haacke E.M., Tang J., Neelavalli J. Susceptibility mapping as a means to visualize veins and quantify oxygen saturation. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging. 2010;32:663–676. doi: 10.1002/jmri.22276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haacke E.M., Liu S., Buch S. Quantitative susceptibility mapping: current status and future directions. Magn. Reson. Imaging. 2015;33:1–25. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2014.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris N.G., Mironova Y.A., Chen S.F. Preventing flow-metabolism un-coupling acutely reduces axonal injury after traumatic brain injury. J. Neurotrauma. 2012;29:1469–1482. doi: 10.1089/neu.2011.2161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He X., Yablonskiy D.A. Biophysical mechanisms of phase contrast in gradient echo MRI. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2009;106:13558–13563. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904899106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hovda D.A., Yoshino A., Kawamata T. Diffuse prolonged depression of cerebral oxidative metabolism following concussive brain injury in the rat: a cytochrome oxidase histo-chemistry study. Brain Res. 1991;567:1–10. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)91429-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh M.C., Tsai C.Y., Liao M.C. Quantitative susceptibility mapping-based microscopy of magnetic resonance venography (QSM-mMRV) for in vivo morphologically and functionally assessing cerebromicrovasculature in rat stroke model. PLoS One. 2016;11 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0149602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iraji A., Chen H., Wiseman N. Connectome-scale assessment of structural and functional connectivity in mild traumatic brain injury at the acute stage. Neuro Image Clin. 2016;12:100–115. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2016.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain V., Langham M.C., Wehrli F.W. MRI estimation of global brain oxygen consumption rate. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2010;30:1598–1607. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2010.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain V., Magland J., Langham M., Wehrli F.W. High temporal resolution in vivo blood oximetry via projection-based T2 measurement. Magn. Reson. Med. 2013;70:785–790. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King N.S. Emotional, neuropsychological, and organic factors: their use in the prediction of persisting postconcussion symptoms after moderate and mild head injuries. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 1996;61:75–81. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.61.1.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King N.S., Crawford S., Wenden F.J. The Rivermead Post Concussion Symptoms Questionnaire: a measure of symptoms commonly experienced after head injury and its reliability. J. Neurol. 1995;242:587–592. doi: 10.1007/BF00868811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King N.S., Crawford S., Wenden F.J. Early prediction of persisting post-concussion symptoms following mild and moderate head injuries. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 1999;38:15–25. doi: 10.1348/014466599162638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnamurthy L.C., Liu P., Ge Y., Lu H. Vessel-specific quantification of blood oxygenation with T2-relaxation-under-phase-contrast MRI. Magn. Reson. Med. 2014;71:978–989. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu T., Khalidov I., de Rochefort L. A novel background field removal method for MRI using projection onto dipole fields (PDF) NMR Biomed. 2011;24:1129–1136. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S., Buch S., Chen Y. Susceptibility-weighted imaging: current status and future directions. NMR Biomed. 2017;30 doi: 10.1002/nbm.3552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LosoiH Silverberg N.D., Wäljas M. Recovery from mild traumatic brain injury in previously healthy adults. J. Neurotrauma. 2016;33:766–776. doi: 10.1089/neu.2015.4070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin N.A., Patwardhan R.V., Alexander M.J. Characterization of cerebral hemodynamic phases following severe head trauma: hypoperfusion, hyperemia, and vasospasm. J. Neurosurg. 1997;87:9–19. doi: 10.3171/jns.1997.87.1.0009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAllister T.W., Sparling M.B., Flashman L.A. Neuroimaging findings in mild traumatic brain injury. J. Clin. Exp. Neuropsychol. 2001;23:775–791. doi: 10.1076/jcen.23.6.775.1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCredie V.A., Piva S., Santos M. The impact of red blood cell transfusion on cerebral tissue oxygen saturation in severe traumatic brain injury. Neurocrit. Care. 2017;26:247–255. doi: 10.1007/s12028-016-0310-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDaniel P., Bilgic B., Fan A.P., Stout J.N., Adalsteinsson E. Mitigation of partial volume effects in susceptibility-based oxygenation measurements by joint utilization of magnitude and phase (JUMP) Magn. Reson. Med. 2017;77:1713–1727. doi: 10.1002/mrm.26227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordström A., Edin B.B., Lindström S. Cognitive function and other risk factors for mild traumatic brain injury in young men: nationwide cohort study. BMJ. 2013;346:f723. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearl M., Gregg L., Gandhi D. Cerebral venous development in relation to developmental venous anomalies and vein of Galen aneurysmal malformations. Semin. Ultrasound CT MR. 2011;32:252–263. doi: 10.1053/j.sult.2011.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potter S., Leigh E., Wade D. The Rivermead Post Concussion Symptoms Questionnaire: a confirmatory factor analysis. J. Neurol. 2006;253:1603–1614. doi: 10.1007/s00415-006-0275-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prins M.L., Lee S.M., Fujima L.S. Increased cerebral uptake and oxidation of exogenous betaHB improves ATP following traumatic brain injury in adult rats. J. Neurochem. 2004;90:666–672. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02542.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweser F., Deistung A., Lehr B.W., Reichenbach J.R. Quantitative imaging of intrinsic magnetic tissue properties using MRI signal phase: an approach to in vivo brain iron metabolism? NeuroImage. 2011;54:2789–2807. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.10.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Y., Kou Z., Kreipke C.W. In vivo measurement of tissue damage, oxygen saturation changes and blood flow changes after experimental traumatic brain injury in rats using susceptibility weighted imaging. Magn. Reson. Imaging. 2007;25:219–227. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2006.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith S.M. Fast robust automated brain extraction. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2002;17:143–155. doi: 10.1002/hbm.10062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun H., Zheng M., Wang Y. Brain tissue partial pressure of oxygen predicts the outcome of severe traumatic brain injury under mild hypothermia treatment. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2016;12:2125–2129. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S102929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahata K., Tabuchi H., Mimura M. Late-onset neurodegenerative diseases following traumatic brain injury: chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) and Alzheimer's disease secondary to TBI (AD-TBI) Brain Nerve. 2016;68:849–857. doi: 10.11477/mf.1416200517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang J., Liu S., Neelavalli J. Improving susceptibility mapping using a threshold-based K-space/image domain iterative reconstruction approach. Magn. Reson. Med. 2013;69:1396–1407. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia S., Utriainen D., Tang J. Decreased oxygen saturation in asymmetrically prominent cortical veins inpatients with cerebral ischemic stroke. Magn. Reson. Imaging. 2014;32:1272–1276. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2014.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu B., Liu T., Spincemaille P., Prince M., Wang Y. Flow compensated quantitative susceptibility mapping for venous oxygenation imaging. Magn. Reson. Med. 2014;72:438–445. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The sensitivity, specificity, and AUC of susceptibility of the cerebral veins for the discrimination between mTBI patients, non-AI patients, AI patients and HCs using ROC.