Abstract

A food-borne outbreak of gastroenteritis with more than 650 suspected cases occurred in April 2016 in Sollentuna, Sweden. It originated in a school kitchen serving a total of 2,700 meals daily. Initial microbiological testing (for Campylobacter, Salmonella, Shigella, Yersinia, Giardia, Cryptosporidium, Entamoeba histolytica, adeno-, astro-, noro-, rota- and sapovirus) of stool samples from 15 symptomatic cases was negative, despite a clinical presentation suggestive of calicivirus. Analyses of the findings from both the Sollentuna municipality environmental team and a web-based questionnaire suggested that the source of the outbreak was the salad buffet served on 20 April, although no specific food item could be identified. Subsequent electron microscopic examination of stool samples followed by whole genome sequencing revealed a variant of sapovirus genogroup V. The virus was not detected using standard PCR screening. This paper describes the epidemiological outbreak investigation and findings leading to the discovery.

Keywords: epidemiology, foodborne infection, gastrointestinal disease, molecular methods, outbreaks, Sapovirus, viral infections, Calicivirus

Introduction

Sapovirus causes acute gastroenteritis in humans and belongs to the Caliciviridae family, along with norovirus and three other genera [1]. Since the virus was first described in 1976, it has been studied and sapoviruses pathogenic to humans are currently classified into four genogroups [1]. Sapovirus has a worldwide distribution and is a common cause of sporadic gastroenteritis [2-4]. Outbreaks may occur in different settings throughout the year, although the reported outbreaks are fewer than for norovirus. Prevalence is highly variable without any apparent geographical pattern. Prevalence and genotype distribution have shifted over time [5]. Food-borne transmission has been suspected on several occasions [6-8]. A recent summary and analysis of reported food-borne outbreaks in the European Union in 2011 estimated that viruses were the cause in 13% of those outbreaks in which a causative agent was verified or where such outbreaks were associated with sufficient solid data to be categorised as viral outbreaks supported by strong evidence; a majority of these (98%) were caused by the Caliciviridae family, specifically noroviruses [9].

On the weekend of 22–24 April 2016, a suspected outbreak of gastroenteritis among students and teachers at four schools in Sollentuna, Sweden, was reported to the municipality of Sollentuna. The initial report stated that more than 50 students and teachers were ill. The Sollentuna municipality environmental team notified the Department of Communicable Disease Control and Prevention in Stockholm on 25 April. All schools in Sollentuna, as well as some outside the municipality, received food from the same central school kitchen, based in one of the affected schools. An outbreak control team was set up to investigate the magnitude of the outbreak and to identify the causative agent of the gastroenteritis in order to localise the source of the outbreak. This report describes the epidemiological investigation and findings, as well as the implemented control measures.

Methods

The outbreak control team included representatives from the Department of Communicable Disease Control and Prevention in Stockholm and the Sollentuna municipality environmental team. The Public Health Agency of Sweden and the National Food Agency were responsible for the microbiological analyses undertaken during the late phase of the outbreak investigation.

Descriptive epidemiology

Early on, the investigation revealed that the central kitchen served 2,700 meals per day at 21 schools and preschools, suggesting that a considerably higher proportion of schools in the Stockholm area could have been exposed than was initially thought. The age of students at the 21 schools and preschools ranged from 1 to 15 years.

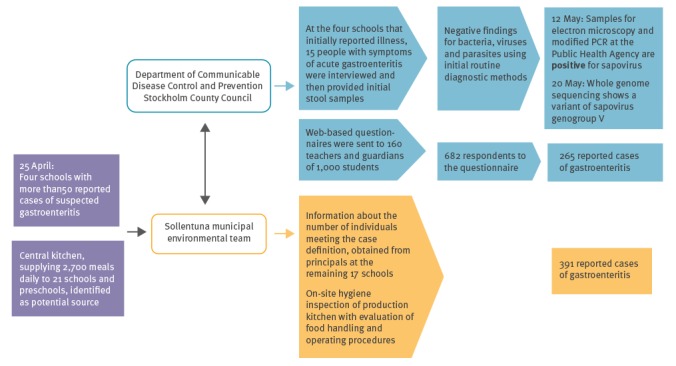

In order to estimate the magnitude of the outbreak, the principals at the school distributed a web-based questionnaire that was provided by the Department of Communicable Disease Control and Prevention in Stockholm to students’ parents, guardians and teachers. Because quick and early distribution was a priority, only the students and teachers at the four schools were included that had initially reported the outbreak to the Sollentuna municipality environmental team. Approximately 1,000 students (6–15 years of age) and 160 teachers attended these four schools, which was considered a sufficient number for meaningful analysis. The questionnaire was distributed by email on the morning of 26 April with a 7-day submission deadline. In addition, to obtain a more complete picture of the magnitude of the outbreak, the Sollentuna municipality environmental team requested that the remaining 17 schools served by the central kitchen estimated the number of students and personnel with gastroenteritis symptoms (Figure 1). Data pertaining to whether the schools received both salad buffet and warm meals were also gathered.

Figure 1.

Communication and important moments in the outbreak investigation, food-borne gastroenteritis outbreak, Sollentuna, Sweden, April 2016 (n = 656)

Purple fields: outbreak background information; blue fields: investigation by the Department of Communicable Disease Control and Prevention; yellow fields: investigation by the Sollentuna municipality environmental team. Open arrows: information received by the Sollentuna municipality environmental team; filled arrows: response measures including simultaneously (i) stool sampling for microbial analysis, (ii) distribution of questionnaires and (iii) information gathering as a basis for case finding among individuals who had consumed food prepared in a central school kitchen in Sollentuna municipality, Stockholm, Sweden in April 2016. A total of 656 gastroenteritis cases were reported.

The Sollentuna municipality environmental team was responsible for the environmental investigation, including inspection of the kitchen, review of hygienic procedures and staff hygiene, procedures for safe handling of raw meat, as well as procedures for heating and cooling food. Interviews were conducted with kitchen personnel. Food samples were taken and when possible, attempts were made to trace them back to the source. Stool samples for microbiological analysis were obtained from 15 people with symptoms of gastroenteritis.

Case definition and case findings

Initial reports indicated that sporadic cases were reported as early as on 21 April; therefore, we decided to ask about manifestation of symptoms after 20 April. For the purposes of our analytical investigation, a case of gastroenteritis was defined as someone who gave a positive response to the question ‘Have you had symptoms of gastroenteritis after 20 April’ among students and teachers at any of the four schools that had first notified Sollentuna municipality about the outbreak.

Secondary cases of gastroenteritis were defined as individuals who did not attend any of these four schools, but belonged to a household where a primary case of gastroenteritis was identified as defined above, and who presented with symptoms of gastroenteritis beginning within 72 hours of the primary case.

The case definition of gastroenteritis from the other 17 schools, as reviewed by the Sollentuna municipality environmental team, was based on absences due to gastroenteritis after 22 April self-reported to administrative personnel at these schools.

Analytical epidemiology

Data collection and analysis

The web-based questionnaire included questions about whether the respondents were teachers or students and about their grade level. Also included was information on clinical manifestations, onset and duration of symptoms, as well as questions regarding potential secondary cases. Early telephone interviews with the parents/guardians of 15 of the sick individuals showed onset of symptoms 12–36 hours after the most recent consumption of food at school, high rates of nausea, vomiting and diarrhoea, as well as short (1–2 days) duration of symptoms, which together suggest that the gastroenteritis was probably caused by a virus rather than bacteria, parasites or toxins. The incubation period for the most common viral gastrointestinal illnesses is short, usually 1–2 days [10]. Given the clinical picture and the short incubation period for the most likely viral agents, the form included detailed questions about what food items were consumed at lunch on 20–22 April (assuming a probable incubation period of 1–2 days).

We analysed the distribution of cases by time of onset of symptoms and demographic characteristics, as well as attack rates and unadjusted risk ratios (RR) of gastroenteritis in relation to consumption of each food item. Unadjusted RR were calculated using Episheet [11].

Microbiological investigations

Stool samples were collected for analysis from 15 individuals who reported symptoms of gastroenteritis. For logistical reasons, samples were sent to either of two separate clinical microbiological laboratories in Stockholm.

All 15 samples were cultured for Salmonella, Shigella, Campylobacter and Yersinia. Because two samples were not available in sufficient quantity, only 13 samples were analysed using the commercially available qPCR geneXpert (Cepheid, Sunnyvale, United States) proprietary platform (adeno-, astro-, noro-, rota- and sapovirus) for seven of the samples and a sapovirus real-time RT-PCR [12] for six of the samples. Eight samples were analysed by microscopy with appropriate staining to search for parasites.

Only six samples were large enough for further analysis by the Public Health Agency of Sweden using electron microscopy, RT-PCR, real-time RT-PCR and whole genome sequencing (WGS). The RT-PCR was performed using the following primers for sapovirus: forward primers CTCGCCACCTACRAWGCBTGGTT, GCCACCTACGAATCCTGGTTCAT, and CAATTGCATGYTACAACAGCTGGTACAT, and reverse primers CGCGCCTCCATRCTACCACCCCA, CGGRCYTCAAAVSTACCNCCCCA, and TGAGACYGTGACTCTRATRTCCATTGC. The real-time RT-PCR was modified from [12]: forward primers GAYCAGGCYCTCGCYACCTAC, TTGGCCCTCGCCACCTAC, and TTTGAACAAGCTGTGGCRTGCTAC, reverse primer NNCCCTCCATYTCAAACACTA and probes FAM-CTGTACCRCCTATGAACCA-MGB and FAM-CTGYACCACCTATRAACCA-MGB.

Environmental investigation

Inspectors from the Sollentuna municipality environmental team conducted a post-outbreak inspection of the central kitchen on 25 April. Physical inspection and personnel interviews were carried out to assess seven areas: infrastructure and procedures, equipment and facilities, food products and packaging, safe handling and storage, cleaning procedures, compliance with temperature protocols, as well as personal hygiene and food traceability.

Samples were obtained from saved main courses, as well as from batches of frozen vegetables and herbs served on 20–22 April. Samples were also obtained from batches of salad that were delivered to the central kitchen after the outbreak. No salad from delivery before the outbreak was available. All food samples were initially stored at −26 oC by the Sollentuna municipality environmental team and subsequently sent to the National Food Agency for analysis once results from the human samples became available.

Results

Descriptive epidemiology

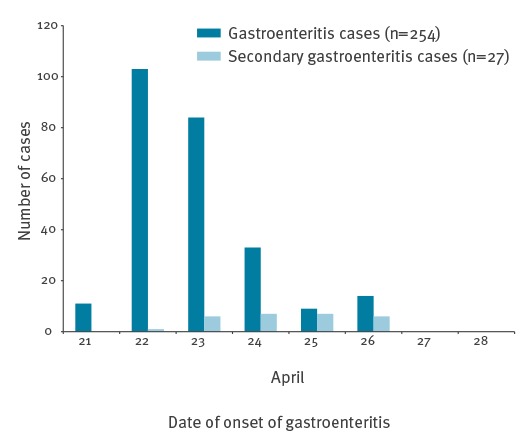

The web-based questionnaire was sent to ca 1,160 people and since all questions were voluntary, the number of responses to each question varied. Of the 682 people (59%) who responded to the question regarding symptoms of gastroenteritis after 20 April, 674 also answered the question concerning sex (363 female and 311 male) and of these, 265 people (39%) reported symptoms of gastroenteritis. Among this latter group, 260 indicated their sex (144 female and 116 male). The attack rate among teachers was 54% (65 of 121), while in students it was 36% (198 of 553). For eight people, information regarding teacher/student status was lacking. The attack rate did not differ significantly between men and women, with 37% (116/311) and 40% (144/360), respectively. Information regarding sex was missing for 11 people. Among all self-reported cases of gastroenteritis, only 10 respondents indicated that they had not eaten in the canteen. Figure 2 shows the distribution of cases by date of onset of gastroenteritis symptoms; cases started to occur on 21 April, followed by a peak on 22 April. Among these cases, 10% (27/281) were reported as secondary cases.

Figure 2.

Epidemic curve of onset of gastroenteritis symptoms among students and teachers at four schools and secondary cases, Sollentuna, Sweden, April 2016 (n = 281)

The summary of the investigation conducted by the Sollentuna municipality environmental team on 25 April showed that 123 teachers and 268 students from the 17 schools not included in the initial investigation had reported symptoms of gastroenteritis (see Table 1). With the addition of these 391 cases, more than 650 people reportedly had gastroenteritis symptoms associated with the outbreak overall.

Table 1. Students/children and teachers reporting symptoms of gastroenteritis after consuming food provided by a central school kitchen to 17 preschools and schools, Sollentuna, Sweden April 2016 (n = 391).

| Received warm meals | Received salad buffet | Teachers with GE symtomsa |

Students/children with GE symptomsa |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| School/preschool 1 | Yes | No | 0 | 0 |

| School/preschool 2 | Yes | Yes | 8 | 1 |

| School/preschool 3 | Yes | Yes | 5 | 15 |

| School/preschool 4 | Yes | No | 0 | 0 |

| School/preschool 5 | Yes | Yes | 3 | NA |

| School/preschool 6 | Yes | Yes | 7 | 5 |

| School/preschool 7 | Yes | Yes | 6 | 21 |

| School/preschool 8 | Yes | Yes | 1 | 1 |

| School/preschool 9 | Yes | No | 0 | 0 |

| School/preschool 10 | Yes | Yes | 3 | 4 |

| School/preschool 11 | Yes | Yes | 7 | 6 |

| School/preschool 12 | Yes | Yes | 6 | 5 |

| School/preschool 13 | Yes | Yes | 10 | 17 |

| School/preschool 14 | Yes | Yes | 9 | 10 |

| School/preschool 15 | Yes | Yes | 21 | 78 |

| School/preschool 16 | Yes | Yes | 8 | 32 |

| School/preschool 17 | Yes | Yes | 29 | 73 |

GE: gastroenteritis; NA: not available.

a Self-reported cases according to the school principals; these cases were not included in further analytical investigation since the individuals involved did not receive the web-based questionnaire.

According to the questionnaires, the most prevalent clinical symptoms were nausea (246/265; 93%), abdominal pain (220/265; 83%), vomiting (183/265; 69%), diarrhoea (133/265; 50%) and fever (127/265; 48%). Duration of these symptoms varied somewhat in that vomiting was of shorter duration than diarrhoea (data not shown). Stratifying symptoms by age (6–9 years: n = 65; 10–12 years: n = 54; 13–15 years: n = 69; teachers: n = 66) showed that nausea, diarrhoea and especially fever were more commonly reported by the older age groups (Figure 3). To our knowledge none of the reported cases required hospital admission.

Figure 3.

Proportion of predominant gastroenteritis symptoms in different age groups among students and teachers at four schools, Sollentuna, Sweden, April 2016 (n = 254)

The figure does not include secondary cases.

Analytical epidemiology

The Sollentuna municipality environmental team found (Table 1) that cases of gastroenteritis were reported only from the 14 schools and preschools that received both the main course and the salad buffet, whereas no cases of gastroenteritis were reported from the three schools that did not receive the salad buffet. Analysis of the questionnaires found no specific food item to be associated with confirmed case status. However, consumption of mixed salad, mixed beans or green beans at lunch on 20 April was associated with confirmed case status, with RR of 2.0 (95% confidence interval (CI): 1.6–2.6), 2.1 (95% CI: 1.6–2.6) and 2.0 (95% CI: 1.6–2.6), respectively (Table 2). Food items served on 21 April or 22 April did not show RR above 1.8. Analyses of the findings from both the Sollentuna municipality environmental team and the web-based questionnaire suggested that the source of the outbreak was the salad buffet served on 20 April, although no specific food item could be identified.

Table 2. Attack rate and crude risk ratios for gastroenteritis among students and teachers at four schools, by food item served in the canteen between Wednesday, 20 April and Friday 22 April 2016, Sollentuna, Sweden (n = 265).

| Food item | Attack rate | Risk ratio | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Among exposed | Among unexposed | |||||||

| Cases | Total | % | Cases | Total | % | RR (95% CI) | ||

| Wednesday 20 April |

Pasta | 174 | 387 | 45 | 10 | 37 | 27 | 1.7 (1.0–2.9) |

| Minced meat sauce | 157 | 347 | 45 | 20 | 66 | 30 | 1.5 (1.0–2.2) | |

| Vegetarian sauce | 13 | 31 | 42 | 122 | 283 | 43 | 1.0 (0.6–1.5) | |

| Mixed salad | 48 | 71 | 68 | 76 | 226 | 34 | 2.0 (1.6–2.6) | |

| Green lettuce | 53 | 107 | 50 | 81 | 215 | 38 | 1.3 (1.0–1.7) | |

| Tomatoes | 77 | 140 | 55 | 58 | 184 | 32 | 1.7 (1.3–2.3) | |

| Cucumber | 112 | 231 | 48 | 38 | 112 | 34 | 1.4 (1.0–1-9) | |

| Mixed beans | 41 | 56 | 73 | 91 | 255 | 36 | 2.1 (1.6–2.6) | |

| Carrots | 64 | 129 | 50 | 72 | 188 | 38 | 1.3 (1.0–1.7) | |

| Haricots verts | 37 | 52 | 71 | 89 | 252 | 35 | 2.0 (1.6–2.6) | |

| Thursday 21 April |

Chicken curry | 147 | 323 | 46 | 29 | 84 | 35 | 1.3 (1.0–1.8) |

| Samosas | 17 | 44 | 39 | 116 | 263 | 44 | 0.9 (0.6–1.3) | |

| Rice | 151 | 343 | 44 | 27 | 64 | 42 | 1.0 (0.8–1.4) | |

| Garlic sauce | 23 | 55 | 42 | 106 | 247 | 43 | 1.0 (0.7–1.4) | |

| Green lettuce | 58 | 114 | 51 | 85 | 221 | 38 | 1.3 (1.0–1.7) | |

| Tomatoes | 68 | 130 | 52 | 70 | 195 | 36 | 1.5 (1.1–1.9) | |

| Carrots | 45 | 92 | 49 | 90 | 227 | 40 | 1.2 (0.9–1.6) | |

| Cucumber | 96 | 212 | 45 | 53 | 128 | 41 | 1.1 (0.8–1.4) | |

| Mixed vegetables | 27 | 38 | 71 | 108 | 275 | 39 | 1.8 (1.4–2.3) | |

| Peas | 37 | 70 | 53 | 100 | 249 | 40 | 1.3 (1.0–1.7) | |

| Pears | 24 | 56 | 43 | 106 | 251 | 42 | 1.0 (0.7–1.4) | |

| Mushrooms | 31 | 51 | 61 | 107 | 273 | 39 | 1.6 (1.2–2.0) | |

| Friday 22 April |

Broccoli soup | 83 | 163 | 51 | 91 | 219 | 42 | 1.2 (1.0–1.5) |

| Pancakes | 156 | 379 | 41 | 34 | 68 | 50 | 0.8 (0.6–1.1) | |

| Strawberry jam | 138 | 342 | 40 | 45 | 90 | 50 | 0.8 (0.6–1.0) | |

| Green lettuce | 32 | 66 | 48 | 120 | 279 | 43 | 1.1 (0.8–1.5) | |

| Tomatoes | 46 | 86 | 53 | 101 | 255 | 40 | 1.4 (1.1–1.7) | |

| Carrots | 60 | 130 | 46 | 93 | 218 | 43 | 1.1 (0.9–1.4) | |

| Cucumber | 69 | 151 | 46 | 85 | 203 | 42 | 1.1 (0.9–1.4) | |

| Cauliflower | 16 | 29 | 55 | 129 | 301 | 43 | 1.3 (0.9–1.8) | |

| Baby corn | 29 | 70 | 41 | 117 | 266 | 44 | 0.9 (0.7–1.3) | |

| Mushrooms | 27 | 45 | 60 | 122 | 294 | 41 | 1.4 (1.1–1.9) | |

CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio.

Laboratory investigation

The 15 stool samples were negative for Salmonella, Shigella and Campylobacter. Further analyses on 13 of these 15 samples also returned negative for adeno-, astro-, noro-, rota- and sapovirus. Material in the remaining two samples was not sufficient for virus analysis. All samples were negative for parasites (Giradia, Cryptosporiduim and Entamoeba histolytica). Two samples (sibling cases) were positive for Yersiniaenterocolitica 1A.

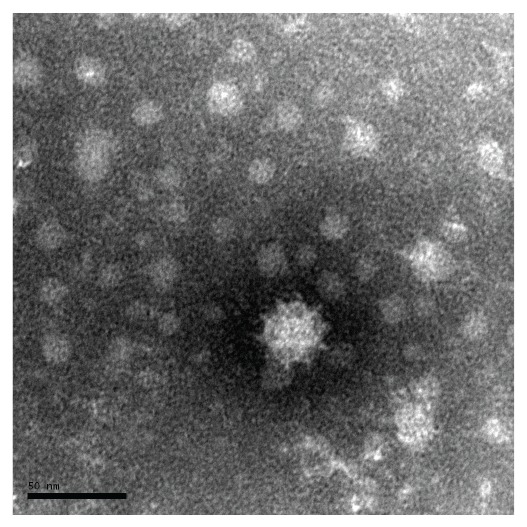

Subsequently, six samples had enough material left to be sent for further analysis to the Public Health Agency of Sweden, which found calicivirus in three of the samples using electron microscopy (Figure 4). All samples were also analysed using RT-PCR and WGS, in which a variant of sapovirus genogroup V was found in five of six samples.

Figure 4.

Electron micrograph of negatively stained sapovirus, gastroenteritis outbreak, Sollentuna, Sweden, April 2016

Scale: bar indicates 50 nm.

Environmental investigation

Among kitchen staff, three of 11 had symptoms of gastroenteritis during the outbreak. Two of the three had eaten the same food as the students. Stool samples collected from the three symptomatic kitchen workers were found to be negative in routine analysis. No specimens from these kitchen workers were among those sent to the Public Health Agency of Sweden.

Post-outbreak measures taken by the central kitchen

At the request of the Sollentuna municipality environmental team, stored frozen food was discarded and the facility, salad bar, cutting boards and utensils were thoroughly cleaned and disinfected.

Analysis of food samples

The central kitchen had been cleaned on the Friday preceding the outbreak and many leftover food items had already been discarded. Therefore, collection of food samples was highly limited or from food unrelated to the outbreak. Frozen parsley had been included in several dishes served on 20 April and sufficient amounts of parsley and green beans remained for analysis.

After results from the human stool samples became available from the Public Health Agency of Sweden, parsley and green beans were sent to the National Food Agency for RT-PCR testing with appropriate primers for sapovirus. Both these food sources were negative. Mixed salad or mixed beans from 20 April were not available.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this food-borne outbreak represents one of the major sapovirus outbreaks since the one in Japan in 2010 [7]. Overall, the Sollentuna outbreak in 2016 involved more than 650 reported cases of gastroenteritis in both children and adults. Sapovirus is known to cause viral gastroenteritis in young children, whereas adults seem to be less affected [2-4]. However, in this outbreak, older students and teachers appeared to be equally or even more affected than young children. The attack rate among teachers was higher than in students. This difference may be due to selection bias as the response rate was 75% among teachers and only 35% among students. This would be true if guardians of asymptomatic students were more likely to respond to the questionnaire, but this seems unlikely.

Assuming that all 2,700 meals served were consumed, causing ca 650 primary cases, this could indicate an attack rate of at least 24%. The most commonly reported symptoms were nausea and abdominal pain, followed by vomiting and diarrhoea. Fever correlated with increasing age in accordance with previous results [13]. Other sapovirus outbreaks have reported fever as the most common symptom and diarrhoea as the least common [13]. Studies comparing genogroup-specific differences and prevalence of various symptoms have found no significant associations to explain the varying clinical presentations in different outbreaks, the reason for which remains unclear [14].

Two siblings were initially found to be positive in stool cultures for Y.enterocolitica 1A. However, there is controversy regarding the pathogenicity of Y.enterocolitica 1A [15] and considering that it was only found in two siblings and no other students, this could not explain the outbreak and was hence considered to be an incidental finding.

No clear source of the outbreak was identified, although food items served in the salad buffet were suspected. The web-based questionnaire showed that mixed salad, mixed beans and green beans all had case-related RR of ca 2.0. Also, the findings of the Sollentuna municipality environmental team implicated the salad buffet (Table 1). Vegetable components including mixed salad and frozen vegetables have been reported in several food-borne outbreaks caused by caliciviruses, more specifically norovirus. Food-borne outbreaks caused by sapovirus are less common [9]. Lack of adequate food samples made it impossible to verify the results by analysing food items. Some studies show that asymptomatic food handlers have high viral loads of sapovirus [6,13,16] and may pose potential risk of secondary transmission. Of 11 kitchen workers, three reported symptoms during the outbreak which coincided with the peak of the outbreak. The questionnaire was available for seven days and as shown in the epidemic curve, symptom onset of some cases occurred almost one week after assumed exposure, which may suggest that these could in fact be secondary cases. However, we have no reason to believe that such secondary cases could have had much impact on the results.

Conclusion

The rapid and efficient multidisciplinary collaboration made it possible to estimate the magnitude of the outbreak, present a descriptive epicurve, provide information to the affected schools, suggest precautions and identify a plausible aetiology (calicivirus) within a few days. Despite the operational efficiency, epidemiological and microbiological evidence remained elusive, while the electron microscopy findings with whole genome sequencing represent a crucial breakthrough. Whole-genome sequencing revealed a sapovirus variant clustering with genogroup V. Phylogenetic analysis of the capsid gene showed that the sequences of S3 and S6 clustered with sapovirus genogroup V but clearly separated from almost all other isolates in the genogroup [17].The investigation of this outbreak clearly demonstrates the importance of epidemiological analysis coupled with both conventional and new microbiological techniques, especially when searching for new variants of infectious agents.

Acknowledgements

The valuable contribution from Malin Forsell and Camilla Östergren in the Sollentuna municipal environmental team as well as Magnus Simonsson at the National Food Agency are all greatly acknowledged.

Conflict of interest: None declared.

Authors’ contributions: The authors have all contributed to the investigation and given valuable input to the manuscript. A writing group (M-PH, JNÖ, PF) prepared the manuscript and contributed equally to study design, data analysis and interpretation. The co-authors (EA, HHA, SH, MI, NL, BS, MT, TT) are presented in alphabetical order.

References

- 1. Oka T, Wang Q, Katayama K, Saif LJ. Comprehensive review of human sapoviruses. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2015;28(1):32-53. 10.1128/CMR.00011-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. de Wit MA, Koopmans MP, Kortbeek LM, Wannet WJ, Vinjé J, van Leusden F, et al. Sensor, a population-based cohort study on gastroenteritis in the Netherlands: incidence and etiology. Am J Epidemiol. 2001;154(7):666-74. 10.1093/aje/154.7.666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rockx B, De Wit M, Vennema H, Vinjé J, De Bruin E, Van Duynhoven Y, et al. Natural history of human calicivirus infection: a prospective cohort study. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;35(3):246-53. 10.1086/341408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Pang XL, Preiksaitis JK, Lee BE. Enhanced enteric virus detection in sporadic gastroenteritis using a multi-target real-time PCR panel: a one-year study. J Med Virol. 2014;86(9):1594-601. 10.1002/jmv.23851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Thongprachum A, Khamrin P, Maneekarn N, Hayakawa S, Ushijima H. Epidemiology of gastroenteritis viruses in Japan: Prevalence, seasonality, and outbreak. J Med Virol. 2016;88(4):551-70. 10.1002/jmv.24387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Usuku S, Kumazaki M, Kitamura K, Tochikubo O, Noguchi Y. An outbreak of food-borne gastroenteritis due to sapovirus among junior high school students. Jpn J Infect Dis. 2008;61(6):438-41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kobayashi S, Fujiwara N, Yasui Y, Yamashita T, Hiramatsu R, Minagawa H. A foodborne outbreak of sapovirus linked to catered box lunches in Japan. Arch Virol. 2012;157(10):1995-7. 10.1007/s00705-012-1394-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Shibata S, Sekizuka T, Kodaira A, Kuroda M, Haga K, Doan YH, et al. Complete Genome Sequence of a Novel GV.2 Sapovirus Strain, NGY-1, Detected from a Suspected Foodborne Gastroenteritis Outbreak. Genome Announc. 2015;3(1):e01553-14. 10.1128/genomeA.01553-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) The European Union summary report on trends and sources of zoonoses, zoonotic agents and food-borne outbreaks in 2011. EFSA J. 2013;11(4):3129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lee RM, Lessler J, Lee RA, Rudolph KE, Reich NG, Perl TM, et al. Incubation periods of viral gastroenteritis: a systematic review. BMC Infect Dis. 2013;13(1):446. 10.1186/1471-2334-13-446 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rothman K. Episheet. [Accessed: May 2017]. Available from: www.krothman.org/episheet.xls

- 12. Oka T, Katayama K, Hansman GS, Kageyama T, Ogawa S, Wu FT, et al. Detection of human sapovirus by real-time reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction. J Med Virol. 2006;78(10):1347-53. 10.1002/jmv.20699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Yoshida T, Kasuo S, Azegami Y, Uchiyama Y, Satsumabayashi K, Shiraishi T, et al. Characterization of sapoviruses detected in gastroenteritis outbreaks and identification of asymptomatic adults with high viral load. J Clin Virol. 2009;45(1):67-71. 10.1016/j.jcv.2009.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lee LE, Cebelinski EA, Fuller C, Keene WE, Smith K, Vinjé J, et al. Sapovirus outbreaks in long-term care facilities, Oregon and Minnesota, USA, 2002-2009. Emerg Infect Dis. 2012;18(5):873-6. 10.3201/eid1805.111843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Stephan R, Joutsen S, Hofer E, Säde E, Björkroth J, Ziegler D, et al. Characteristics of Yersinia enterocolitica biotype 1A strains isolated from patients and asymptomatic carriers. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2013;32(7):869-75. 10.1007/s10096-013-1820-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Franck KT, Lisby M, Fonager J, Schultz AC, Böttiger B, Villif A, et al. Sources of Calicivirus contamination in foodborne outbreaks in Denmark, 2005-2011--the role of the asymptomatic food handler. J Infect Dis. 2015;211(4):563-70. 10.1093/infdis/jiu479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hallström B, Lagerqvist N, Lind-Karlberg M, Helgesson S, Follin P, Hergens M-P, et al. Complete genome sequence of a sapporo virus GV.2 variant from an outbreak in Sweden 2016. Genome Announc. 2017;5(5):e01446-16. 10.1128/genomeA.01446-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]