Abstract

Background

Psychological assessment is not commonly performed nor easily accepted by coloproctological patients. Our aim was to evaluate the psychological component of coloproctological disorders using uncommon tools.

Methods

The 21-Item Depression Anxiety and Stress Scale and the Pescatori projective test were applied to coloproctological outpatients of the Gastroenterology Department of our hospital as well as to healthy volunteers.

Results

Seventy patients (median age 47 years, 22 male) divided in 4 groups (functional constipation, constipated irritable bowel syndrome, benign anorectal disease and perianal Crohn’s disease) and 52 healthy volunteers (age 45 years, 18 male) completed the tests. Proctological patients showed higher scores of depression (P<0.001), anxiety (P<0.001), and stress (P<0.001) compared to healthy participants. Compared to the control group, patients with functional constipation, irritable bowel syndrome and perianal Crohn’s disease maintained the highest scores in all subscales (P<0.05), while patients with benign anorectal disease only had higher anxiety and stress (P<0.001) scores. The patients’ also showed lower scores in the Pescatori projective test (P=0.012). A weak association between the projective test and the depression subscale was found (P=0.05).

Conclusion

Proctological patients had higher scores of depression, anxiety and stress and lower scores in the Pescatori projective test compared to healthy controls.

Keywords: Coloproctological disorders, psychometry, anxiety, stress and depression scales, projective test

Introduction

Benign coloproctological disorders comprise a wide spectrum of diseases: functional constipation (FC), constipated irritable bowel syndrome (IBSc), benign anorectal diseases (BAD) and perianal Crohn’s disease (pCD). Although regarded as nonthreatening conditions, these diseases can be highly symptomatic and have an important impact on patients’ well-being and quality of life [1-4].

Psychological factors appear to play a relevant role in these conditions [5-13]. Although several psychometric instruments have been used to evaluate gastrointestinal patients, only a few studies applied those tests to coloproctological patients [5,9,14-19]. The 21-Item Depression Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS-21) is a well-established instrument for measuring depression, anxiety, and stress using 3 psychometric scales [20-22]. Recently, 2 studies evaluated the psychological component of anorectal diseases in an alternative way using projective graphics tests, such as the “Draw a Human Figure” test [19] and the “Draw a Family” test [14,19]. These tests are simple, easy to execute and well accepted by patients, and may reflect psychopathology and altered emotional states [23-25].

We aimed to characterize the psychological component of some coloproctological conditions by comparing patients to a healthy population in order to determine whether psychological evaluation should be performed as routine.

Patients and methods

We performed a prospective psychological assessment of coloproctological outpatients of the Gastroenterology Department of Braga Hospital between July and December of 2015. Included patients had one of the following diagnoses: 1) FC fulfilling Rome III criteria; 2) IBSc fulfilling Rome III criteria; 3) BAD in the last year (anal fissure, hemorrhoids or anal itching), confirmed by hospital anal examination; and 4) pCD proven by anal ultrasound or pelvic magnetic resonance image. Exclusion criteria were age <18 years, structural constipation and criteria for more than one of the described groups. The control group consisted of healthy volunteers with no psychiatric history or gastrointestinal symptoms, generally other Departments’ outpatients or accompanying persons. The socio-demographic characteristics and clinical history of participants were collected through a questionnaire.

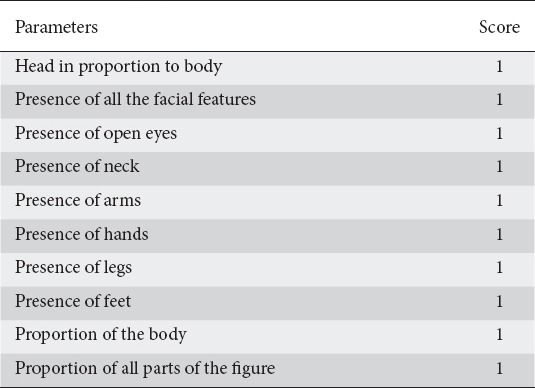

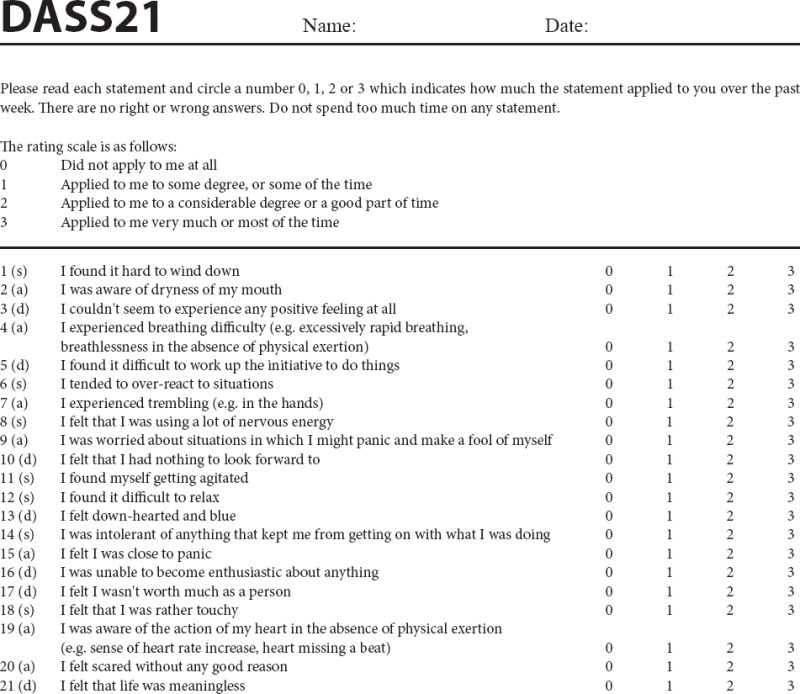

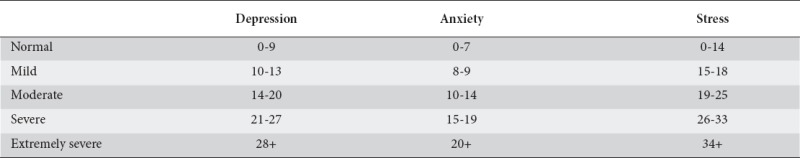

We chose 2 innovative instruments of psychological assessment in this area of expertise: the Portuguese version of DASS-21 [22] and the Pescatori projective test (Ppt) based on the “Draw a Human Figure” test [19]. The validated and published Portuguese version of DASS-21 [20,21,24] assigns a score of 0-3 points to each of the 7 sentences in the subscales of depression, anxiety and stress (Annex 1). The Ppt is based on the “Draw a Human Figure” test developed by Goodenough in 1926 [26] and adapted by Machover in 1949 [27] to evaluate personality traits through graphic design interpretation. The experimental scoring model used in this study was developed by Cioli, Gagliardi and Pescatori in 2015 [19]. This model scores graphic design characteristics (Table 1) and it ranges from 0 (worst result) to 10 (normal) [20,21]. The drawings were evaluated and classified by a psychologist who had no access to the patients’ data.

Table 1.

Pescatori projective test score

The study complied with the standards and recommendations of the Helsinki Declaration. All participants provided informed consent. Anonymity and confidentiality were assured by coding each participant.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed with SPSS 22.0. Statistical significance was achieved with P<0.05. Chi-square tests were used when comparing categorical variables. Non-parametric Mann-Whitney and Kruskall-Wallis tests were performed to compare two or more than two groups, respectively, when data were not normally distributed. Correlation was measured with Spearman’s correlation coefficient.

Results

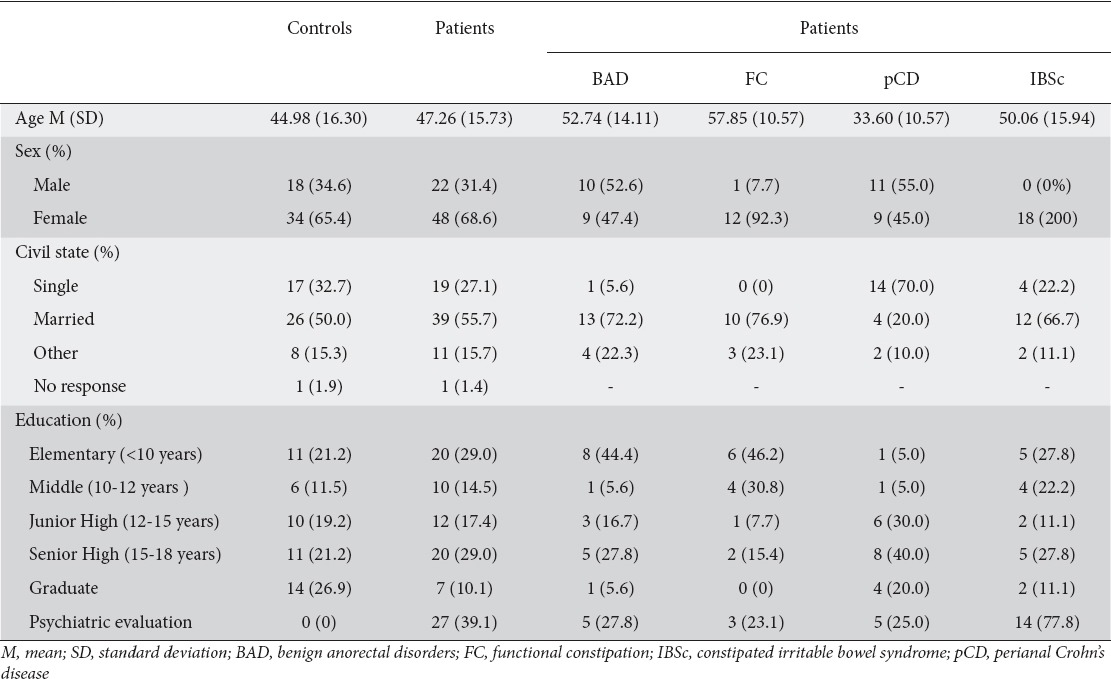

Seventy patients (13 FC, 18 IBSc, 19 BAD, 20 pCD) and 52 healthy individuals were included. There was no significant difference between patients and controls regarding age (P=0.12), sex (P=0.71), marital status (P=0.93), or education (P=0.17). Significant differences were found when comparing the prevalence of a previous psychiatric evaluation (P<0.001) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Demographic data of patients and controls

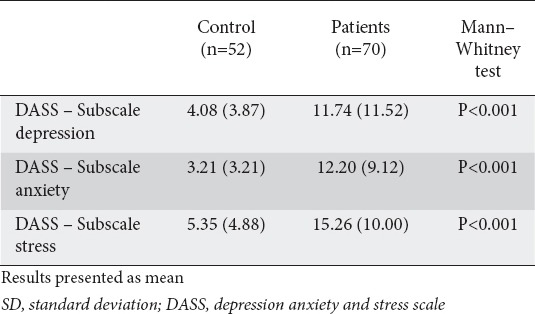

When DASS-21 results were compared, coloproctological patients had higher scores than healthy individuals in the three subscales: depression, anxiety, and stress (P<0.001) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Comparison of DASS-21 between patients and controls

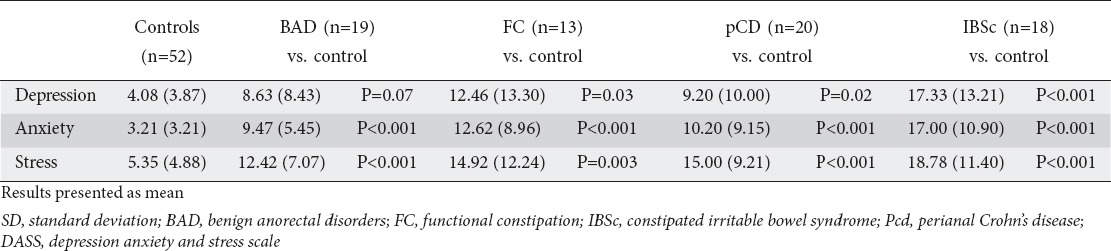

All 4 subgroups had significantly higher scores than controls in all subscales of DASS-21, except for the subscale of depression, in which BAD patients and controls had similar scores (Table 4). There were no significant differences between the subgroups as regards depression (P=0.19), stress (P=0.09) or anxiety (P=0.38).

Table 4.

Comparison of DASS-21 between patient subgroups and controls

Regarding the Ppt, 2 patients from the FC group were excluded because they refused to draw. Globally, coloproctological patients had lower scores (mean=7.03, SD=2.07) than healthy individuals (median=7.96, SD=2.01) (P=0.01). However, in a subgroup analysis, only FC and IBSc patients had significantly lower scores than controls (P=0.04 for both). There were no significant differences between subgroups (P=0.32).

There was an inverse correlation between the Ppt and the depression subscale (r=-0.24, P=0.05) in coloproctological patients.

Discussion

Considering the recognizable psychological component of coloproctological disorders, our question is whether it would be relevant to request a psychological/psychiatric evaluation of these patients at some point during their follow up.

In our study, IBSc and FC patients showed higher scores of depression, anxiety and stress. These results are consistent with the current pathophysiological knowledge of these functional disorders, although most of the research in this area focuses predominantly on IBS [5,6,8,10,28,29].

The BAD patients presented higher levels of anxiety and stress, as described by Smith et al [11]. Anxiety and stress activate the sympathetic nervous system, increasing the internal anal sphincter pressure and potentially causing hemorrhoidal disease and anal fissures [30-32]. Some studies point to stress as the trigger to hypothalamus–pituitary–adrenal axis suppression and consequent chronic pruritus [33]. The BAD patients and healthy volunteers had similar levels of depression. As these are usually more transitory conditions, they have only a minor impact on long-term quality of life and prospects for the future, in contrast to chronic conditions [4,11]. It would be interesting to see if, in cases of long term BAD, this dimension would be affected.

The pCD patients had higher levels of anxiety, stress and depression, in accordance with the literature [12,13,34,35]. Stress and depression may be associated with immunological changes (infiltration of T and B cells, impaired healing, altered levels of defensins) as well as microbiological and genetic factors, all described in the genesis of perianal fistulas [36-38].

No significant differences between subgroups were observed. Likewise, Mikocka-Walus et al evaluated anxiety and stress levels among patients with IBD, IBS and chronic hepatitis C and found no differences between groups [18]. These results suggest that the psychological component in functional and organic coloproctological conditions has an equivalent effect, although a bigger sample might reveal differences between the subgroups.

Coloproctological patients showed significantly lower results in the Ppt compared to healthy individuals, a difference that only achieved significance in the subgroups of FC and IBSc patients. It is probable that, in these functional conditions, the presence of altered personality traits is more evident and more easily detected by the test. Comparably to the DASS-21 results, there were no significant differences between subgroups, something that a larger sample might have altered.

There was a significant inverse correlation only between the subscale of depression and the Ppt, a phenomenon that can be explained by the illustrative/expressive capacity of this projective test, which possibly reflects more the intrapsychic conflict and not the response to external pressure [22].

The present study has several limitations. The Ppt is an experimental test, a fact that adds uncertainty to our conclusions. It may be influenced by age, education, sex, work and even lack of interest/effort in the test. Another limitation was the small number of patients, which did not allow us to see differences between the pathological conditions.

Although the aim of this work was not to discriminate the role of psychological factors as a cause or consequence of coloproctological diseases, our study demonstrates the existence of a clear association. Based on our results, an initial psychological or psychiatric evaluation was proposed to 2 BAD, 8 FC, 1 pCD, and 3 IBSc patients. From our point of view, it seems that the implementation of an early evaluation, with brief, subtle and well-accepted tools that allow the prompt management of the psychological component, could be a pertinent part of care in these patients. This paradigm attitude shift could change the recurrent nature and chronic course of these conditions. The use of preventive strategies could even change the epidemiology and the treatment algorithm of these diseases.

In conclusion, proctological patients had higher scores of depression, anxiety and stress and lower scores in the Ppt. DASS-21 is a ready-to-use instrument helpful in the proctological outpatient setting. Ppt may become a valuable tool that needs further validation. The early diagnosis of the psychological component of the coloproctological functional and organic diseases should be of concern to the physician.

Summary Box.

What is already known:

Benign coloproctological disorders can be highly symptomatic and have an important impact on patients’ well-being and quality of life

Psychological factors may play a relevant role in the described conditions

What the new findings are:

Patients with functional as well as organic coloproctological diseases had higher scores of depression, anxiety, and stress

Benign anorectal conditions (hemorrhoids and anal fissure) had no association with depression

Coloproctological patients had lower scores in the Pescatori projective test

Biography

Braga Hospital; University of Minho, Braga, Portugal

APPENDIX 1

DASS-21 Scoring Instructions

The DASS-21 should not be used to replace a face to face clinical interview. If you are experiencing significant emotional difficulties you should contact your GP for a referral to a qualified professional.

Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale - 21 Items (DASS-21)

The Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale - 21 Items (DASS-21) is a set of three self-report scales designed to measure the emotional states of depression, anxiety and stress.

Each of the three DASS-21 scales contains 7 items, divided into subscales with similar content. The depression scale assesses dysphoria, hopelessness, devaluation of life, self-deprecation, lack of interest / involvement, anhedonia and inertia. The anxiety scale assesses autonomic arousal, skeletal muscle effects, situational anxiety, and subjective experience of anxious affect. The stress scale is sensitive to levels of chronic non-specific arousal. It assesses difficulty relaxing, nervous arousal, and being easily upset / agitated, irritable / over-reactive and impatient. Scores for depression, anxiety and stress are calculated by summing the scores for the relevant items.

The DASS-21 is based on a dimensional rather than a categorical conception of psychological disorder. The assumption on which the DASS-21 development was based (and which was confirmed by the research data) is that the differences between the depression, anxiety and the stress experienced by normal subjects and clinical populations are essentially differences of degree. The DASS-21 therefore has no direct implications for the allocation of patients to discrete diagnostic categories postulated in classificatory systems such as the DSM and ICD.

Recommended cut-off scores for conventional severity labels (normal, moderate, severe) are as follows:

NB Scores on the DASS-21 will need to be multiplied by 2 to calculate the final score.

Lovibond, S.H. & Lovibond, P.F. (1995). Manual for the Depression Anxiety & Stress Scales. (2nd Ed.)Sydney: Psychology Foundation.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: None

References

- 1.Belsey J, Greenfield S, Candy D, Geraint M. Systematic review: impact of constipation on quality of life in adults and children. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;31:938–949. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2010.04273.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Spiegel BM. The burden of IBS: looking at metrics. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2009;11:265–269. doi: 10.1007/s11894-009-0039-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mahadev S, Young JM, Selby W, Solomon MJ. Quality of life in perianal Crohn’s disease: what do patients consider important? Dis Colon Rectum. 2011;54:579–585. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e3182099d9e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Foxx-Orenstein AE, Umar SB, Crowell MD. Common anorectal disorders. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y) 2014;10:294–301. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rao SS, Seaton K, Miller MJ, et al. Psychological profiles and quality of life differ between patients with dyssynergia and those with slow transit constipation. J Psychosom Res. 2007;63:441–449. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2007.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dykes S, Smilgin-Humphreys S, Bass C. Chronic idiopathic constipation: a psychological enquiry. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2001;13:39–44. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200101000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pescatori M, Spyrou M, Pulvirenti d’Urso A. A prospective evaluation of occult disorders in obstructed defection using the ‘iceberg diagram’. Colorectal Dis. 2005;8:785–789. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2006.01138.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fond G, Loundou A, Hamdani N, et al. Anxiety and depression comorbidities in irritable bowel syndrome (IBS): a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2014;264:651–660. doi: 10.1007/s00406-014-0502-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eriksson EM, Andrén KI, Eriksson HT, Kurlberg GK. Irritable bowel syndrome subtypes differ in body awareness, psychological symptoms and biochemical stress markers. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:4889–4896. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.4889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Drossman DA, Camilleri M, Mayer EA, Whitehead WE. AGA technical review on irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:2108–2131. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.37095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith LE, Henrichs D, McCullah RD. Prospective studies on the etiology and treatment of pruritus ani. Dis Colon Rectum. 1982;25:358–363. doi: 10.1007/BF02553616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maconi G, Gridavilla D, Viganò C, et al. Perianal disease is associated with psychiatric co-morbidity in Crohn´s disease in remission. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2014;29:1285–1290. doi: 10.1007/s00384-014-1935-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mahadev S, Young JM, Selby W, Solomon MJ. Self-reported depressive symptoms and suicidal feelings in perianal Crohn’s disease. Colorectal Dis. 2012;14:331–335. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2011.02613.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miliacca C, Gagliardi G, Pescatori M. The ‘Draw-the-Family Test’ in the preoperative assessment of patients with anorectal diseases and psychological distress: a prospective controlled study. Colorectal Dis. 2010;12:792–798. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2009.01985.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Muscatello MR, Bruno A, Pandolfo G, et al. Depression, anxiety and anger in subtypes of irritable bowel syndrome patients. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2010;17:64–70. doi: 10.1007/s10880-009-9182-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kovács Z, Seres G, Kerékgyártó O, Czobor P. Psychopathological symptom dimensions in patients with gastrointestinal disorders. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2010;17:378–386. doi: 10.1007/s10880-010-9212-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Simrén M, Svedlund J, Posserud I, Björnsson ES, Abrahamsson H. Health-related quality of life in patients attending a gastroenterology outpatient clinic: functional disorders versus organic diseases. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:187–195. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(05)00981-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mikocka-Walus AA, Turnbull DA, Andrews JM, et al. Psychological problems in gastroenterology outpatients: A South Australian experience. Psychological co-morbidity in IBD, IBS and hepatitis C. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health. 2008;4:15. doi: 10.1186/1745-0179-4-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cioli VM, Gagliardi G, Pescatori M. Psychological stress in patients with anal fistula. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2015;30:1123–1129. doi: 10.1007/s00384-015-2245-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lovibond SH, Lovibond PF. Manual for the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales. Sydney: Psychology Foundation of Australia; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Henry JD, Crawford JR. The short-form version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS-21): construct validity and normative data in a large non-clinical sample. Br J Clin Psychol. 2005;44:227–239. doi: 10.1348/014466505X29657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pais-Ribeiro JL, Honrado A, Leal I. Contribuição para o Estudo da Adaptação Portuguesa das Escalas de Ansiedade, Depressão e Stress (EADS) de 21 Itens de Lovibond e Lovibond. Psicologia, Saúde & Doenças. 2004;5:229–239. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Handler L, Campbell A, Martin B. Use of graphic techniques in personality assessment: reliability, validity, and clinical utility. In: Hersen M, Hilsenroth MJ, Segal DL, editors. Comprehensive handbook of psychological assessment – Volume 2: Personality assessment. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2004. pp. 387–404. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Handler L. Anxiety indexes in the draw a person test: a scoring manual. J Proj Tech Pers Assess. 1967;31:46–57. doi: 10.1080/0091651X.1967.10120375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weiner I, Roger L. Handbook of personality assessment. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goodenough FL. Measurement of intelligence by drawings. New York: World Book; 1926. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Machover K. Personality projection: in the drawing of a human figure. Springfield, IL: Charles C Thomas Publisher; 1949. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Salvioli B, Pellegatta G, Malacarne M, et al. Autonomic nervous system dysregulation in irritable bowel syndrome. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2015;27:423–430. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moloney RD, Johnson AC, O’Mahony SM, Dinan TG, Greenwood-Van Meerveld B, Cryan JF. Stress and the microbiota-gut-brain axis in visceral pain: Relevance to irritable bowel syndrome. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2016;22:102–117. doi: 10.1111/cns.12490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zaghiyan KN, Fleshner P. Anal fissure. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2011;24:22–30. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1272820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Loder PB, Kamm MA, Nicholls RJ, Phillips RK. Haemorrhoids: pathology, pathophysiology and aetiology. Br J Surg. 1994;81:946–954. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800810707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carlstedt A, Nordgren S, Fasth S, Appelgren L, Hultén L. Sympathetic nervous influence on the internal anal sphincter and rectum in man. Int J Colorectal Dis. 1988;3:90–95. doi: 10.1007/BF01645312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tey HL, Wallengren J, Yosipovitch G. Psychosomatic factors in pruritus. Clin Dermatol. 2013;31:31–40. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2011.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bannaga AS, Selinger CP. Inflammatory bowel disease and anxiety: links, risks, and challenges faced. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2015;8:111–117. doi: 10.2147/CEG.S57982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cámara RJ, Schoepfer AM, Pittet V, Begré S, von Känel R Swiss Inflammatory Bowel Disease Cohort Study (SIBDCS) Group. Mood and nonmood components of perceived stress and exacerbation of Crohn´s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17:2358–2365. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moons WG, Shields GS. Anxiety, not anger, induces inflammatory activity: An avoidance/approach model of immune system activation. Emotion. 2015;15:463–476. doi: 10.1037/emo0000055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Marshall GD., Jr The adverse effects of psychological stress on immunoregulatory balance: applications to human inflammatory diseases. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2011;31:133–140. doi: 10.1016/j.iac.2010.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tozer PJ, Whelan K, Phillips RK, Hart AL. Etiology of perianal Crohn’s disease: role of genetic, microbiological, and immunological factors. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15:1591–1598. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]