Abstract

Pityriasis rosea (PR) is a common erythemato-squamous dermatosis which almost always, is easily diagnosed. Mostly the disease presents in its classical form. However, clinical dermatology is all about variations and PR is not an exception. Variants of the disease in some cases may be troublesome to diagnose and confuse clinicians. Prompt diagnosis and treatment of the condition becomes necessary to avoid unnecessary investigations. We hereby review and illustrate atypical presentations of the disease, including diverse forms of location and morphology of the lesions, the course of the eruption, and its differential diagnoses.

Keywords: Pityriasis, Pityriasis rosea, Pityriasis rosea of Gibert, Herald patch, Papulo-squamous dermatosis

Core tip: Pityriasis rosea (PR) is a common, self-limited disease which in its typical form should not raise diagnostic doubts. Atypical forms represent 20% of cases, with diverse variants with respect to morphology and location of lesions, and evolution of the disease. Recognition of these forms may avoid unnecessary procedures. Drug ingestion may simulate PR in some cases.

INTRODUCTION

Pityriasis rosea (PR) is a relatively common, self-limited papulo-squamous dermatosis of unknown origin, which mainly appears in adolescents and young adults (10-35 years), slightly more common in females. It has a sudden onset, and in its typical presentation, the eruption is preceeded by a solitary patch termed “herald patch”, mainly located on the trunk. Few days later, a secondary eruption appears, with little pink, oval macules, with a grayish peripheral scaling collarette around them. The secondary lesions adopt a characteristic distribution along the cleavage lines of the trunk, with a configuration of a “Christmas tree”. In most cases, the eruption lasts for 6 to 8 wk. Its incidence has been estimated to be 0.68% of dermatologic patients[1], varying from 0.39%[2] to 4.8%[3].

Not so rarely (20%)[4,5], an atypical eruption may develop, concerning several aspects about the morphology or distribution of the lesions, their symptomatology and evolution.

The purpose of this article is to review and illustrate the diverse clinical presentations of PR (Table 1), which may vary in morphology, symmetry, duration, size and distribution of lesions, mucosal involvement and symptomatology.

Table 1.

Clinical classification of pityriasis rosea

| Classical adult PR and pediatric PR |

| Based on herald patch |

| No herald patch |

| Only herald patch (absence of secondary lesions) |

| Multiple herald patches |

| Herald patch in atypical location |

| Based on location of lesions |

| Limited to scalp |

| Limited to trunk |

| Limited to limbs-girdle (pityriasis circinata et marginata of Vidal) |

| Limited to flexures (inverse type) |

| Limited to the extremities |

| Acral type |

| Along the lines of Blaschko |

| Unilateral |

| Based on morphology of lesions |

| Purpuric or hemorrhagic |

| Urticarial |

| Erythema multiforme-like |

| Papular |

| Follicular |

| Vesicular |

| Giant |

| Hypopigmented |

| Irritated |

| Based on course of the disease |

| Relapsing |

| Recurrent |

| Persisting |

| Relapsing and persisting |

| PR-like rashes (drug-induced) |

PR: Pityriasis rosea.

Classical PR

A classical PR is preceeded by the herald patch, an erythematous round or oval lesion, 2-5 cm in diameter, ocassionally covered by fine scales (Figure 1). Prodromal symptoms, consisting of headache, general malaise, or flu-like symptoms are ocassionally encountered. Few days later (5-15 d), a secondary rash appears, consisting of similar, but smaller lesions, mainly located on the trunk (Figure 2). Pruritus is usually mild or absent, but can vary in intensity. The eruption lasts for 4-6 wk and fades, leaving no sequelae. Generally, it only appears once throughout life. In 75% of patients the lesions appear between the ages of 10-35 years[6].

Figure 1.

Herald patch. Solitary erythemato-squamous lesion, sharply defined, round or oval, mainly located on the trunk or proximal extremities.

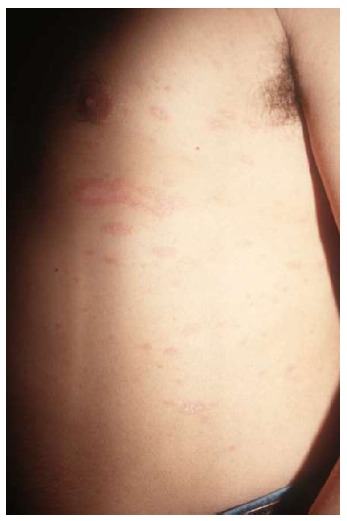

Figure 2.

Classical pityriasis rosea. Exanthematous eruption with erythemato-squamous lesions following cleavage lines on the trunk.

Pediatric PR

Infrequently PR may affect children (Figure 3), with a prevalence between 8%[7] to 12%[6] below 10 years and 4% below 4 years of age[6] in Caucasians, whereas in dark-skinned children it increases to 26%[8]. Papular lesions prevail in them, with a short period between the herald patch and the general eruption (4 d vs 14 d in adults), and a shorter duration of the exanthema (16 d vs 45 d). The majority of cases have been described in children with ages between 3 to 9 years old, contrasting with the illustrated case of 8-mo, showing a classical variant. About half of the cases show prodromal symptoms[7].

Figure 3.

Pediatric pityriasis rosea. Typical lesions of PR affecting an 8-mo-old boy. PR: Pityriasis rosea.

BRIEF DESCRIPTION OF CLINICAL VARIANTS OF PR

Herald patch in atypical location

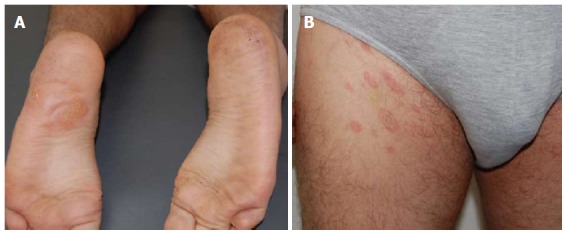

Although not mentioned in the literature, we had the opportunity to come across a patient who presented with a herald patch on a sole, and a secondary classical eruption on the trunk and proximal aspect of the extremities (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Herald patch in atypical location. Herald patch on a sole (A) and (B) typical PR eruption affecting trunk and proximal thighs. PR: Pityriasis rosea.

Circinata and marginata PR

Seen mainly in adults with few and large lesions only located on limbs-girdle, hips, shoulders, axillae or inguinal regions[9-11].

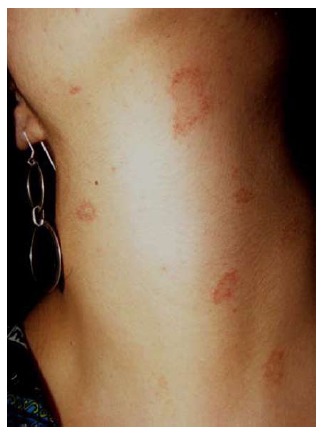

Inversus PR

The lesions are located on flexural areas (axillae, groins), face, neck (Figure 5), and acral areas (palms and soles), without affecting the trunk[12].

Figure 5.

Inversus pityriasis rosea. Lesions distributed on face and neck in two patients; the trunk is not affected.

PR of extremities

In this variant, the lesions are confined to the extremities, with typical squamous plaques (Figure 6). The trunk is not affected.

Figure 6.

Pityriasis rosea of the extremities. Lesions affecting only the extremities in two different cases, without trunk involvement.

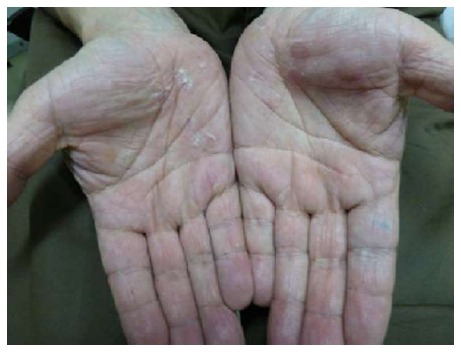

Acral PR

The lesions are exclusively located on palms, wrists, soles[13] (Figure 7), without involvement of the flexures (axillae, groins and face), opposite to inversus PR.

Figure 7.

Acral pityriasis rosea. Desquamation affecting the palms.

Purpuric or hemorrhagic PR

Macular purpuric lesions and petechiae may appear over different locations (Figure 8) including the palate. Purpuric lesions have also appeared bilaterally on the legs in a man with a typical rash on the trunk, affecting the lines of cleavage and with collarette scaling[4].

Figure 8.

Purpuric pityriasis rosea. Round and oval purpuric lesions affecting the neck of a young woman.

Urticarial PR

Palpable itchy wheals-like lesions with peripheral collarette scaling (Figure 9) following the lines of skin cleavage[4,10].

Figure 9.

Urticarial pityriasis rosea. Palpable edematous, erythematous lesions with collarette scaling.

Erythema multiforme-like PR

In some cases, classical lesions of PR may be accompanied by targetoid lesions resembling erythema multiforme (Figure 10). It presents with papulosquamous lesions, admixed with few targetoid lesions distributed on the trunk, face, neck or arms[14,15]. There is no history of herpes simplex infection.

Figure 10.

Erythema multiforme-like pityriasis rosea. Annular and papular lesions resembling erythema multiforme.

Papular PR

Multiple small papular lesions, 1-3 mm in diameter with peripheral collarette, located on the trunk and proximal extremities, along the skin cleavage lines (Figure 11). It appears predominantly in young patients[4].

Figure 11.

Papular pityriasis rosea. A: Papular lesions with peripheral collarette (Courtesy of Priyankar Misra, Junior Resident, Dermatology, Burdwan Medical College, West Bengal, India); B: Herald patch on the neck and disseminated discrete papular eruption in a girl.

Follicular PR

It has been described in a 9-year-old boy with predominantly follicular scaly lesions, arranged in annular configuration[16]. The initial lesions consisted of pruritic plaques mainly located on the abdomen, thighs and groins; five days later, a striking follicular eruption - with central clearing and a peripheral collarette- developed on the posterior trunk. Prodromal symptoms included sore throat, malaise and low grade fever (Figure 12).

Figure 12.

Follicular pityriasis rosea. Follicular lesions with scaling (Courtesy of Shankila Mittal, Junior Resident, Dermatology, Maulana Azad Medical College, New Delhi, India).

Vesicular PR

Generalized itchy eruption of vesicles of 2-6 mm in diameter with a rosette scaling has been described in young adults and children[17-21] (Figure 13).

Figure 13.

Vesicular pityriasis rosea. Vesicular lesions surrounding round to oval plaques (Courtesy of Dibyendu Basu, Junior Resident, Dermatology, Medical College and Hospital, Kolkata, West Bengal, India).

Gigantea PR of darier

The dimensions of the herald patch is greater than usual, being described with the size and shape of a pear[22] (Figure 14).

Figure 14.

Giant pityriasis rosea. Large herald patch (Courtesy of Soumya Jagadeesan, Assistant Professor, Dermatology, Amrita Institute of Medical Sciences, Kochi, Kerala, India).

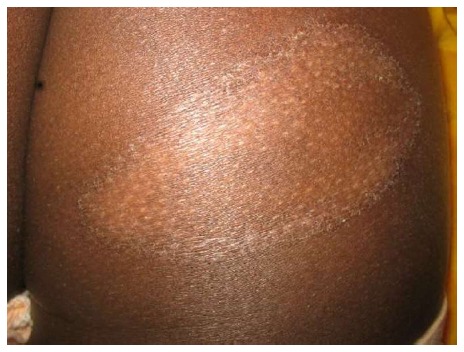

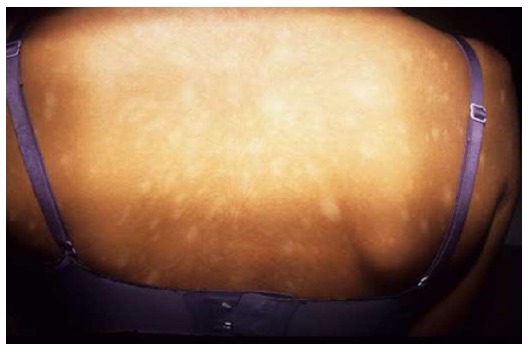

Hypopigmented PR

It is essentially similar to the classic PR, with a preceding herald patch and a secondary eruption, but with hypopigmented lesions from the beginning, mainly distributed on the trunk (Figure 15). It is more frequent in dark-skinned individuals. It should not be confused with secondary hypopigmentation after a common PR.

Figure 15.

Hypopigmented pityriasis rosea. Round to oval hypopigmented lesions during the whole course of the eruption.

Irritated PR

A PR with severe itch, pain and burning sensation on contact with sweat[5,23] (Figure 16).

Figure 16.

Irritated pityriasis rosea. Symptomatic eczematous lesions (Courtesy of Dipti Das, Consultant Dermatologist, Dr Marwah’s Skin Clinic, Mumbai, Maharashtra, India).

Relapsing PR

It usually recurs within one year of the first episode, among 2.8%-3.7% of patients[8,24]. Relapses usually show absence of herald patch, and the size and number of secondary lesions are smaller. The duration of this episode is shorter and with less constitutional symptoms. Multiple relapses - though rare - have been described[25,26].

Persistent PR

By definition it lasts more than 3 mo. Its incidence in a series was 2%[1]. Most patients (75%) show a herald patch[1] and complain of systemic symptoms (most commonly fatigue, or headache, insomnia, irritability). The eruption persists for 12-24 wk. Oral lesions are common (75%), principally strawberry tongue, erythematous macules, vesicular lesions and petechiae.

Recurrent PR

Rarely, there can be multiple episodes of PR in a lifetime[25-27].

Relapsing and persisting PR

It has been described in a young man with three episodes of PR within one year-fulfilling the criteria for relapsing PR, and the last episode during 7 mo-consistent with persistent PR. Noteworthy, the patient presented with multiple oral ulcers[28].

Oral involvement in PR

Oral lesions in PR are more common in dark skinned people[29]. The lesions are difficult to differentiate from aphthous ulcers. Its appearance should coincide with a generalized eruption with the characteristics of PR[4]. The lesions may be punctate, erosive, bullous or hemorrhagic. They disappear concomitantly as the skin eruption fades.

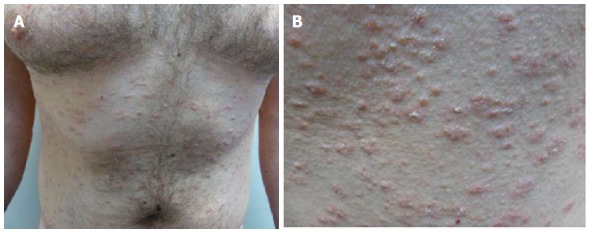

PR-like rashes

They consist of exanthematous rashes which appear following the intake of several drugs: ACE inhibitors[30-32], gold[33-36], isotretinoin[37], non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents[38,39], omeprazole[40], terbinafine[41], and tyrosine-kinase inhibitors[42]. Many of them resemble PR vaguely (Figure 17), so it may be considered as a separate condition. There is no previous herald patch and the eruption is monomorphous.

Figure 17.

Pityriasis rosea-like rash. A: The eruption in this case was probably related to the ingestion of levothyroxine in a 33-year-old man, extensively affecting the trunk; B: The lesions are small and monomorphous (Courtesy of Dr. Elizabeth Rendic).

DISCUSSION

PR is a self-limited, acute inflammatory dermatosis, which occasionally could be persistent or recurrent. In rare situations, the symptoms or presentation may be troublesome, thus making difficulty in diagnosis or having a significant impact on the patient’s quality-of-life. Its etiology has not been clearly established, but a viral origin has been suspected for years.

Recently, there are increasing evidences to suggest the role of human herpes virus (HHV) in the etiopathogenesis of PR[43,44]. Additional evidences suggest that PR is associated with reactivation of HHV 6-7[44]. Diminished levels of natural killer cells and B-cell activity in the lesions of PR has been observed. This suggests the role of a T-cell mediated immunity. Besides, increased amounts of CD4 T cells and Langerhans cells have been found in the dermis, which possibly points towards viral antigen processing and presentation. However, this matter is still debated since some individuals are infected with HHV 6-7 and do not develop the disease. PR has been also reported following vaccinations as well (Bacillus Calmette-Guerin, influenza, H1N1, diphtheria, smallpox, hepatitis B, pneumococcus, etc.)[45,46].

The diagnosis of PR is essentially clinical (Table 2)[47], and in rare circumstances a biopsy may be required. Histological features are not specific and include focal parakeratosis, hypogranulosis, spongiosis, papillary dermal edema, mild perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate, exocytosis and extravasated erythrocytes in the papillary dermis.

Table 2.

Diagnostic criteria of pityriasis rosea[47]

| Mandatory clinical features |

| Discrete circular or oval lesions |

| Scaling within most lesions |

| Peripheral collarette scaling |

| Optional clinical features |

| Trunk and proximal limb distribution |

| Distribution along cutaneous cleavage lines |

| Previous herald patch |

Differential diagnosis[48]

Secondary syphilis: Meticulous history taking, previous history of chancre, lymphadenopathy, positive VDRL test, histology showing plasma cells and endarteritis obliterans are suggestive. Lesions of secondary syphilis are monomorphous and always asymptomatic; they almost always affect palms and soles.

Dermatophytosis: It may be troublesome to differentiate when the only lesion of PR is the herald patch. However, a mycotic lesion expands progressively and shows a clear center, whereas herald patch remains inalterable. Positive KOH mount is the pointer.

Guttate psoriasis: History of sore throat, presence of rain-drop pattern and histology are important clues. Scales are thicker and silvery-white.

Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus: Photosensitivity is the rule. Besides, histology shows epidermal atrophy and basal layer degeneration.

Rarely, primary HIV infection, seborrhoeic dermatitis, drug rash, erythema multiforme and cutaneous T cell lymphoma may also be confused with PR. Hypopigmented variant may be confused with pityriasis alba (lesions are mainly located on the face or arms and it is usually associated with atopic dermatitis), hypopigmented mycosis fungoides (lesions are large, persistent, and mainly distributed on buttocks and lower trunk), and progressive macular hypomelanosis of the trunk (lesions are slowly progressive, tend to coalesce, and do not show desquamation).

Therapeutic options

Many cases require no treatment at all, only reassurance directed to the patients, underlying the benign nature and self-limited duration of the disease, which do not leave sequelae and that other members of their family or friends will be not affected. Therapeutic options when needed (in the case of many or symptomatic lesions) include the use of emollients and topical corticosteroids, and antihistamines when itching.

The use of oral macrolides (erythromycin and azithromycin) have shown controversial results[49,50]. Initially, these were found to be beneficial but recent studies show that macrolides are ineffective in the management of PR.

Since the current concepts of etiopathogenesis may imply the role of HHV-7 and HHV-6 in the causation of PR, antivirals like acyclovir have been found to show good response[51-54]. The effectiveness of phototherapy is debated and further studies need to be conducted[55,56]. A statement about the management of PR has been recently raised[57]. Main conclusions include an adequate diagnosis, impact of the eruption in the quality of life since many patients do not necessitate any treatment, and use of oral acyclovir 400 mg three times daily for seven days, when not contraindicated or possible adverse effects are suspected.

CONCLUSION

The diagnosis of typical PR should not be difficult for any dermatologist. Nevertheless, its atypical presentations - as defined here - can be a challenge for the clinician. We hope the article will be helpful to the clinicians, in identifying numerous variants of this common disease.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest statement: Authors declare no conflict of interests for this article.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: Chile

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

Peer-review started: February 9, 2017

First decision: March 7, 2017

Article in press: April 19, 2017

P- Reviewer: Firooz A, Hu SCS, Sadighha A, Vasconcellos C S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL

References

- 1.Drago F, Broccolo F, Ciccarese G, Rebora A, Parodi A. Persistent pityriasis rosea: an unusual form of pityriasis rosea with persistent active HHV-6 and HHV-7 infection. Dermatology. 2015;230:23–26. doi: 10.1159/000368352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.de Souza Sittart JA, Tayah M, Soares Z. Incidence pityriasis rosea of Gibert in the Dermatology Service of the Hospital do Servidor Público in the state of São Paulo. Med Cutan Ibero Lat Am. 1984;12:336–338. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Olumide Y. Pityriasis rosea in Lagos. Int J Dermatol. 1987;26:234–236. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1987.tb00907.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chuh A, Zawar V, Lee A. Atypical presentations of pityriasis rosea: case presentations. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2005;19:120–126. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2004.01105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.González LM, Allen R, Janniger CK, Schwartz RA. Pityriasis rosea: an important papulosquamous disorder. Int J Dermatol. 2005;44:757–764. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2005.02635.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chuang TY, Ilstrup DM, Perry HO, Kurland LT. Pityriasis rosea in Rochester, Minnesota, 1969 to 1978. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1982;7:80–89. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(82)80013-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Drago F, Ciccarese G, Broccolo F, Cozzani E, Parodi A. Pityriasis Rosea in Children: Clinical Features and Laboratory Investigations. Dermatology. 2015;231:9–14. doi: 10.1159/000381285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Drago F, Ciccarese G, Rebora A, Broccolo F, Parodi A. Pityriasis Rosea: A Comprehensive Classification. Dermatology. 2016;232:431–437. doi: 10.1159/000445375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jacyk WK. Pityriasis rosea in Nigerians. Int J Dermatol. 1980;19:397–399. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1980.tb03738.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Klauder JV. Pityriasis rosea with particular reference to its unusual manifestations. JAMA. 1924;82:178–83. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sarkany I, Hare PJ. Pityriasis rotunda. (pityriasis circinata) Br J Dermatol. 1964;76:223–228. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1964.tb14514.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gibney MD, Leonardi CL. Acute papulosquamous eruption of the extremities demonstrating an isomorphic response. Inverse pityriasis rosea (PR) Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:651, 654. doi: 10.1001/archderm.133.5.651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zawar V. Acral pityriasis rosea in an infant with palmoplantar lesions: A novel manifestation. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2010;1:21–23. doi: 10.4103/2229-5178.73253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Das A, Sarkar TK, Chandra S, Ghosh A, Gharami RC. A case series of erythema multiforme-like pityriasis rosea. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2016;7:212–215. doi: 10.4103/2229-5178.182374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Relhan V, Sinha S, Garg VK, Khurana N. Pityriasis rosea with erythema multiforme - like lesions: an observational analysis. Indian J Dermatol. 2013;58:242. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.110855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zawar V, Chuh A. Follicular pityriasis rosea. A case report and a new classification of clinical variants of the disease. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2012;6:36–39. doi: 10.3315/jdcr.2012.1095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anderson CR. Dapsone treatment in a case of vesicular pityriasis rosea. Lancet. 1971;2:493. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(71)92662-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garcia RL. Letter: Vesicular pityriasis rosea. Arch Dermatol. 1976;112:410. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Griffiths A. Vesicular pityriasis rosea. Arch Dermatol. 1977;113:1733–1734. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Friedman SJ. Pityriasis rosea with erythema multiforme-like lesions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;17:135–136. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(87)80542-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bari M, Cohen BA. Purpuric vesicular eruption in a 7-year-old girl. Vesicular pityriasis rosea. Arch Dermatol. 1990;126:1497, 1500–1501. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1990.01670350111020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pringle JJ. Case presentation, section on dermatology, Royal Society of Medicine. Br J Dermatol. 1915;27:309. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eslick GD. Atypical pityriasis rosea or psoriasis guttata? Early examination is the key to a correct diagnosis. Int J Dermatol. 2002;41:788–791. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.2002.01627.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bjornberg A, Hellgren L. Pityriasis rosea. A statistical, clinical, and laboratory investigation of 826 patients and matched healthy controls. Acta Derm Venereol Suppl (Stockh) 1962;42(Suppl 50):1–68. doi: 10.2340/0001555542168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Halkier-Sørensen L. Recurrent pityriasis rosea. New episodes every year for five years. A case report. Acta Derm Venereol. 1990;70:179–180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zawar V, Kumar R. Multiple recurrences of pityriasis rosea of Vidal: a novel presentation. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:e114–e116. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2008.03167.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Singh SK, Singh S, Pandey SS. Recurrent pityriasis rosea. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 1998;64:237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chuah SY, Chia HY, Tan HH. Recurrent and persistent pityriasis rosea: an atypical case presentation. Singapore Med J. 2014;55:e4–e6. doi: 10.11622/smedj.2013190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Drago F, Broccolo F, Rebora A. Pityriasis rosea: an update with a critical appraisal of its possible herpesviral etiology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:303–318. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2008.07.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wilkin JK, Kirkendall WM. Pityriasis rosea-like rash from captopril. Arch Dermatol. 1982;118:186–187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rotstein E, Rotstein H. Drug eruptions with lichenoid histology produced by captopril. Australas J Dermatol. 1989;30:9–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-0960.1989.tb00400.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ghersetich I, Rindi L, Teofoli P, Tsampau D, Palleschi GM, Lotti T. [Pityriasis rosea-like skin eruptions caused by captopril] G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 1990;125:457–459. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hofmann C, Burg G, Jung C. Cutaneous side effects of gold therapy. Clinical and histologic results. Z Rheumatol. 1986;45:100–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wilkinson SM, Smith AG, Davis MJ, Mattey D, Dawes PT. Pityriasis rosea and discoid eczema: dose related reactions to treatment with gold. Ann Rheum Dis. 1992;51:881–884. doi: 10.1136/ard.51.7.881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lizeaux-Parneix V, Bedane C, Lavignac C, Bernard P, Bonnetblanc JM. Cutaneous reactions to gold salts. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1994;121:793–797. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bonnetblanc JM. Cutaneous reactions to gold salts. Presse Med. 1996;25:1555–1558. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Helfman RJ, Brickman M, Fahey J. Isotretinoin dermatitis simulating acute pityriasis rosea. Cutis. 1984;33:297–300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Corke CF, Meyrick TR, Huskisson EC, Kirby JD. Pityriasis rosea-like rashes complicating drug therapy for rheumatoid arthritis. Br J Rheumatol. 1983;22:187–188. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/22.3.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yosipovitch G, Kuperman O, Livni E, Avinoach I, Halevy S. Pityriasis rosea-like eruption after anti-inflammatory and antipyretic medication. Harefuah. 1993;124:198–200, 247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Buckley C. Pityriasis rosea-like eruption in a patient receiving omeprazole. Br J Dermatol. 1996;135:660–661. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1996.tb03863.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gupta AK, Lynde CW, Lauzon GJ, Mehlmauer MA, Braddock SW, Miller CA, Del Rosso JQ, Shear NH. Cutaneous adverse effects associated with terbinafine therapy: 10 case reports and a review of the literature. Br J Dermatol. 1998;138:529–532. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1998.02140.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Konstantopoulos K, Papadogianni A, Dimopoulou M, Kourelis C, Meletis J. Pityriasis rosea associated with imatinib (STI571, Gleevec) Dermatology. 2002;205:172–173. doi: 10.1159/000063900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Drago F, Malaguti F, Ranieri E, Losi E, Rebora A. Human herpes virus-like particles in pityriasis rosea lesions: an electron microscopy study. J Cutan Pathol. 2002;29:359–361. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0560.2002.290606.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Broccolo F, Drago F, Careddu AM, Foglieni C, Turbino L, Cocuzza CE, Gelmetti C, Lusso P, Rebora AE, Malnati MS. Additional evidence that pityriasis rosea is associated with reactivation of human herpesvirus-6 and -7. J Invest Dermatol. 2005;124:1234–1240. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2005.23719.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Oh CW, Yoon J, Kim CY. Pityriasis rosea-like rash secondary to intravesical bacillus calmette-guerin immunotherapy. Ann Dermatol. 2012;24:360–362. doi: 10.5021/ad.2012.24.3.360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Papakostas D, Stavropoulos PG, Papafragkaki D, Grigoraki E, Avgerinou G, Antoniou C. An atypical case of pityriasis rosea gigantea after influenza vaccination. Case Rep Dermatol. 2014;6:119–123. doi: 10.1159/000362640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chuh AA. Diagnostic criteria for pityriasis rosea: a prospective case control study for assessment of validity. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2003;17:101–103. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-3083.2003.00519_4.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mahajan K, Relhan V, Relhan AK, Garg VK. Pityriasis Rosea: An Update on Etiopathogenesis and Management of Difficult Aspects. Indian J Dermatol. 2016;61:375–384. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.185699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bukhari IA. Oral erythromycin is ineffective in the treatment of pityriasis rosea. J Drugs Dermatol. 2008;7:625. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pandhi D, Singal A, Verma P, Sharma R. The efficacy of azithromycin in pityriasis rosea: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2014;80:36–40. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.125484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Drago F, Vecchio F, Rebora A. Use of high-dose acyclovir in pityriasis rosea. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:82–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2005.06.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rassai S, Feily A, Sina N, Abtahian S. Low dose of acyclovir may be an effective treatment against pityriasis rosea: a random investigator-blind clinical trial on 64 patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:24–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2010.03676.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ganguly S. A Randomized, Double-blind, Placebo-Controlled Study of Efficacy of Oral Acyclovir in the Treatment of Pityriasis Rosea. J Clin Diagn Res. 2014;8:YC01–YC04. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2014/8140.4360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Das A, Sil A, Das NK, Roy K, Das AK, Bandyopadhyay D. Acyclovir in pityriasis rosea: An observer-blind, randomized controlled trial of effectiveness, safety and tolerability. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2015;6:181–184. doi: 10.4103/2229-5178.156389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Castanedo-Cazares JP, Lepe V, Moncada B. Should we still use phototherapy for Pityriasis rosea? Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2003;19:160–161. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0781.2003.00029.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lim SH, Kim SM, Oh BH, Ko JH, Lee YW, Choe YB, Ahn KJ. Low-dose Ultraviolet A1 Phototherapy for Treating Pityriasis Rosea. Ann Dermatol. 2009;21:230–236. doi: 10.5021/ad.2009.21.3.230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chuh A, Zawar V, Sciallis G, Kempf W. A position statement on the management of patients with pityriasis rosea. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:1670–1681. doi: 10.1111/jdv.13826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]