Abstract

Synthetic cannabinoids have become a common drug of abuse in recent years and their toxicities have come to light as well. They are known to be notorious for the kidneys, with acute tubular necrosis, acute interstitial nephritis and rhabdomyolysis induced renal injury being the frequent nephrotoxic outcomes in users. We report a case of bilateral renal cortical necrosis, leading to irreversible renal damage and lifelong dialysis dependency.

Keywords: Synthetic cannabinoids, Renal cortical necrosis, Dialysis

Core tip: Renal cortical necrosis is a debilitating condition and has a number of causes, in our case a 47 years old female suffered from this condition after smoking synthetic cannabinoids (SCBs) which are a new form of synthetic illicit designer drugs. The patient presented with nausea for 5 d along with anuria for past 24 h before presentation. On laboratory findings the patient had thrombocytopenia while clinically the patient had thrombotic microangiopathy which leads to bilateral renal cortical necrosis. Patient was placed permanently on hemodialysis. Thus awareness needs to be dispersed about potential effects of SCBs.

INTRODUCTION

Synthetic cannabinoids (SCBs) are classified as new psychoactive substances (NPS). There are various types of SCBs available, K2, and Spice being the most popular products. They have gained popularity among peddlers and users because not all are listed as controlled substances, they are freely available, they are relatively inexpensive and most importantly they are not detectable by routine drug screening methods[1].

SBCs have a wide array of adverse effects and toxicities, ranging from nausea to agitation, seizures, stroke and multi-organ failure. These adverse effects led 28531 patients to the emergency departments in the United States in 2011[2]. We report a case of bilateral cortical necrosis associated with the use of SCBs.

CASE REPORT

A 47-year-old Caucasian female presented to the emergency department with complaints of nausea and vomiting for 5 d along with hallucinations, abdominal pain and severe back pain with hematuria which progressed to anuria over the next 24 h. She admitted to smoking marijuana and stated that she had recently switched to a new dealer and smoked SCB 5 d ago. Past medical history included thyroid cancer status post thyroidectomy followed by radioactive iodine therapy 10 years ago, interosseous lipoma, hyperlipidemia, history of poly-substance abuse, tobacco abuse and history of bipolar disorder.

On physical exam she was ill appearing, hypotensive with a blood pressure of 71/48 mmHg. Pupils were 2 mm in size and sluggish. Lung exam noted diminished breath sounds in the left lower lobe along with bilateral costo-vertebral angle tenderness.

The patient was admitted to the intensive care unit, intravenous fluid bolus was initiated and nephrology service was consulted. Blood cultures were obtained to rule out sepsis, serum toxicology was positive for benzodiazepines and tetrahydrocannabinol. Laboratory results showed WBC 33.4 × 109/L, Platelets 84 × 109/L, Creatinine 6.13 mg/dL, BUN 49 mg/dL, Total CK 3603 U/L, ALT 1016 U/L, AST 716 U/L, D-dimer 25.95 mcg/mL, Fibrinogen 493.5 mg/dL, LDH 1983 U/L, Hepatitis viral serology was negative as well as antinuclear antibody, complements, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, anticardiolipin antibody and blood cultures. For the first 24 h the patient remained hypotensive and anuric. Abdominal cat scan showed a striated appearance of both kidneys. Hemodialysis was initiated on day three.

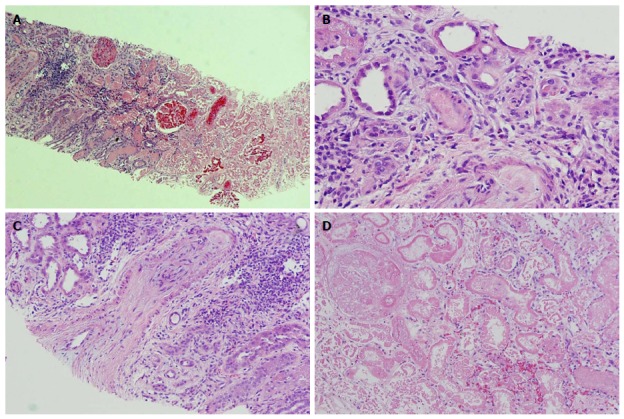

Computed tomography (CT) guided kidney biopsy was obtained on day ten. The biopsy contained adequate amount of renal cortex with 19 glomeruli. Except for the corticomedullary junction, the entire cortex was necrotic (Figure 1A and B). At the corticomedullary junction, an arcuate artery had severely obliterating mucoid to fibrous intimal thickening (Figure 1C). Occasional arterioles at the corticomedullary junctions were obliterated by amorphous material, most likely platelet and fibrin thrombi (Figure 1D). Some interstitial inflammation was evident at the corticomedullary junction (Figure 1A and D). The renal medulla was viable. The tissue for immunofluorescence and electron microscopy represented a completely necrotic renal cortex (pictures not shown). The biopsy findings were consistent with a severe form of thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA) causing renal cortical necrosis.

Figure 1.

Renal pathology. Pathological findings: A: Corticomedullary junction. The right side is necrotic renal cortex. On the left side of the image there is still viable corticomedullary junction. H and E, × 40; B: An arteriole obliterated with amorphous material (platelet and fibrin thrombus). H and E, × 200; C: An arcuate artery with almost completely obliterated lumen by severe fibrous to mucoid intimal thickening at the corticomedullary junction. H and E, × 100; D: Necrotic renal cortex without nuclear staining in the cells. H and E, × 200.

DISCUSSION

This case illustrates the extent of toxicity of SCBs with recreational use. Use of SCBs has been reported to be associated with devastating renal outcomes and multi-organ failure in patients. Most of these reports suggested prerenal azotemia and rhabdomyolysis as the cause of acute tubular necrosis[1].

In 2013 the center for disease control reported a case series of 16 patients who developed acute kidney injury while using SCBs[3]. Majority (93.8%) of the patients presented with nausea and vomiting, 12 (75%) patients had either abdominal pain or flank pain and only 1 patient had anuria.

Physiological effects of SCB’s are similar but more intense than cannabinoids. This is related to the greater binding affinity to cannabinoid receptors centrally and peripherally as well as their active metabolites that contribute to the intensity of their effects[4]. Similar to cannabinoids and following a brief pressor phase, SCB’s can cause longstanding hypotension and bradycardia as a result of a decrease in the sympathetic tone[5]. Non-neural sites of the cannabinoids action on the vascular smooth muscle and endothelial cells can also add to the degree of systemic hypotension[6]. Animal studies in canines and rodents using different vascular beds suggested a direct effect of cannabinoids on smooth muscle cells mediated through the modulation of calcium and potassium cellular transport resulting in hyperpolarization and relaxation[7,8]. Cannabinoids also have endothelial-dependent effects on the vascular beds. This can be initiated by binding to CB1 receptors on the surface of the endothelial cell and to a different type of receptor that might not be specific to the class of cannabinoids[6].

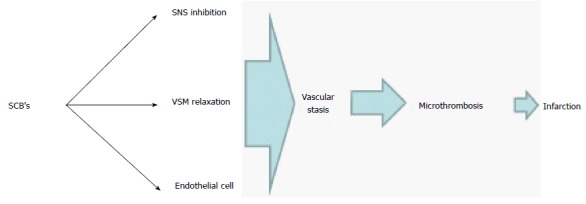

Taken all together, it is reasonable to state that SCB is a more potent drug than the natural cannabinoids can potentially result in major vascular compromise followed by stasis secondary to vascular paralysis. This state can result in anoxic endothelial cell damage that leads to thrombotic microangipathy. In our patient, this is suggested by laboratory markers of compromised organ perfusion along with thrombocytopenia. Figure 2 illustrates the mechanism of TMA in this patient.

Figure 2.

Proposed mechanism of synthetic cannabinoids-induced thrombotic microangiopathy. Prolonged hypotension secondary to the inhibitory effect of the SCBs on the sympathetic tone and vascular smooth muscle cells along with endothelial release of nitric oxide can lead to stasis followed by endothelial ischemia and microthrombosis leading to renal cortical necrosis. SCBs: Synthetic cannabinoids; SNS: Sympathetic nervous system; VSM: Vascular smooth muscle.

Alternative etiologies of TMA were either ruled out or were unlikely in this patient with a temporal relationship between the exposure and the onset of clinical manifestations. An underlying tendency or inherited alternative complement pathway abnormalities as in hemolytic uremic syndrome is also unlikely, as the systemic presentation was suggestive of multi-organ intense hypoperfusion rather than primary renal involvement. Moreover, the normal complement levels, although a nonspecific finding, add to this argument. To our knowledge, this is the first case that shows biopsy proven cortical necrosis due to SCB use. Three years later, our patient is still dialysis dependent.

COMMENTS

Case characteristics

A 47-year-old Caucasian female presented to the emergency department with complaints of nausea and vomiting for 5 d along with hallucinations, abdominal pain and severe back pain with hematuria which progressed to anuria after smoking synthetic cannabinoids (SCBs).

Clinical diagnosis

Ill appearing, hypotensive patient with bilateral costo-vertebral angle tenderness.

Differential diagnosis

Acute renal failure, acute tubular necrosis, renal cortical necrosis.

Laboratory diagnosis

Laboratory investigations showed thrombocytopenia, acute renal failure, while serologies for autoimmune diseases were negative.

Imaging diagnosis

Abdominal computed tomography showed bilateral striated kidneys.

Pathological diagnosis

Cortical necrosis.

Treatment

Hemodialysis and supportive treatment.

Related reports

Thrombotic microangiopathy occurs because of endothelial injury to the capillaries and arterioles. It is has numerous causes but it has rarely been attributed to have been caused by Marijuana use.

Term explanation

SCBs are new and potent synthetic illicit designer drugs.

Experiences and lessons

This condition presented with signs of hypotension and acute renal failure, even after the conventional treatment, there was no response or improvement in the symptoms of the patient. Thus, patients suspected of marijuana or synthetic cannabinoid use should be probed for a pertinent history which will be vital for diagnosis and timely treatment. More awareness needs to be created about SCBs and their potential side effects.

Peer-review

The manuscript is interesting.

Footnotes

Supported by Internal Medicine Department, Joan C Edwards School of Medicine, Marshall University.

Institutional review board statement: This case report was exempt from the Institutional Review Board standards at Marshall University, Huntington, WV, United States.

Informed consent statement: The patient involved in this study gave her written informed consent authorizing use and disclosure of her protected health information.

Conflict-of-interest statement: All the authors have no conflicts of interests to declare.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Peer-review started: February 7, 2017

First decision: March 7, 2017

Article in press: April 24, 2017

P- Reviewer: Mehdi I, Sergi CM S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL

References

- 1.Pendergraft WF, Herlitz LC, Thornley-Brown D, Rosner M, Niles JL. Nephrotoxic effects of common and emerging drugs of abuse. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;9:1996–2005. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00360114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Drug Abuse Warning Network, 2011: National Estimates of Drug-Related Emergency Department Visits. HHS Publication No. (SMA) 13-4760, DAWN Series D-39. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Acute kidney injury associated with synthetic cannabinoid use--multiple states, 2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62:93–98. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Castaneto MS, Gorelick DA, Desrosiers NA, Hartman RL, Pirard S, Huestis MA. Synthetic cannabinoids: epidemiology, pharmacodynamics, and clinical implications. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014;144:12–41. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kunos G, Járai Z, Bátkai S, Goparaju SK, Ishac EJ, Liu J, Wang L, Wagner JA. Endocannabinoids as cardiovascular modulators. Chem Phys Lipids. 2000;108:159–168. doi: 10.1016/s0009-3084(00)00194-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hillard CJ. Endocannabinoids and vascular function. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2000;294:27–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gebremedhin D, Lange AR, Campbell WB, Hillard CJ, Harder DR. Cannabinoid CB1 receptor of cat cerebral arterial muscle functions to inhibit L-type Ca2+ channel current. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:H2085–H2093. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.276.6.H2085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Randall MD, Alexander SP, Bennett T, Boyd EA, Fry JR, Gardiner SM, Kemp PA, McCulloch AI, Kendall DA. An endogenous cannabinoid as an endothelium-derived vasorelaxant. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;229:114–120. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.1766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]