Abstract

There is no curative treatment for advanced bladder cancer. Causing ubiquitinated protein accumulation and endoplasmic reticulum stress is a novel approach to cancer treatment. The HIV protease inhibitor ritonavir has been reported to suppress heat shock protein 90 and increase the amount of unfolded proteins in the cell. If the proteasome functions normally, however, they are rapidly degraded. We postulated that the novel proteasome inhibitor ixazomib combined with ritonavir would kill bladder cancer cells effectively by inhibiting degradation of these unfolded proteins and thereby causing ubiquitinated proteins to accumulate. The combination of ritonavir and ixazomib induced drastic apoptosis and inhibited the growth of bladder cancer cells synergistically. The combination decreased the expression of cyclin D1 and cyclin‐dependent kinase 4, and increased the sub‐G1 fraction significantly. Mechanistically, the combination caused ubiquitinated protein accumulation and endoplasmic reticulum stress. The combination‐induced apoptosis was markedly attenuated by the protein synthesis inhibitor cycloheximide, suggesting that the accumulation of ubiquitinated proteins played an important role in the combination's antineoplastic activity. Furthermore, the combination induced histone acetylation cooperatively and the decreased expression of histone deacetylases was thought to be one mechanism of this histone acetylation. The present study provides a theoretical basis for future development of novel ubiquitinated‐protein‐accumulation‐based therapies effective against bladder cancer.

Keywords: Bladder cancer, drug combinations, ixazomib, ritonavir, ubiquitinated proteins

There is no curative treatment for patients with advanced bladder cancer. Cisplatin‐based chemotherapies have been widely used for metastatic disease, but their efficacy is limited. The overall survival for metastatic bladder cancer patients treated with a standard cisplatin–gemcitabine regimen was reported to be only 14.0 months.1 Clearly a novel treatment strategy is urgently needed.

Causing ubiquitinated protein accumulation and thereby inducing endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress is a novel approach to cancer treatment.2 Unfolded proteins are often repaired by molecular chaperones such as heat shock protein (HSP) 90, and if the repair fails they are ubiquitinated and degraded by the proteasome.3 Therefore, to cause ubiquitinated protein accumulation effectively, one needs to inhibit both the proteasome and the molecular chaperones.4

Our laboratory has been investigating ways to cause ubiquitinated protein accumulation and ER stress in urological cancer cells efficiently. Because developing new agents requires huge amounts of time and money, we have been using already available drugs in combination for our research projects in the context of drug repositioning. Our previous studies combining drugs that inhibit molecular chaperones, such as histone deacetylase inhibitors and HIV protease inhibitors, with a proteasome inhibitor have shown that ubiquitinated protein accumulation and ER stress kills renal cancer cells5, 6 and prostate cancer cells7 effectively. This strategy is thus thought to be promising against urological cancer, but it has not been tested in bladder cancer cells. Furthermore, those studies did not clearly show that a drug combination's cytotoxicity was associated with ubiquitinated protein accumulation.

In the present study, we used two already available drugs to inhibit molecular chaperones and to inhibit the proteasome. Ritonavir is an HIV protease inhibitor widely used for the treatment of HIV infection and has recently been shown to suppress the function of HSP90.8 Ixazomib is a novel proteasome inhibitor that has been given to multiple myeloma patients in a phase II trial.9 In the present study using bladder cancer cells, we have investigated the abilities of ritonavir and ixazomib alone and together to kill bladder cancer cells, the ability of the combination to cause ubiquitinated protein accumulation and ER stress, and the relationship between ubiquitinated protein accumulation and the combination's cytotoxicity.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture

Bladder cancer cells (UMUC3, J82, and 5637) were obtained from ATCC (Rockville, MD, USA). They were cultured in MEM or RPMI medium supplemented with 10% FBS and 0.3% penicillin–streptomycin (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and grown at 37°C in a fully humidified 95% air–5% CO2 atmosphere.

Reagents

Ritonavir purchased from Toronto Research Chemicals (North York, ON, Canada) and ixazomib purchased from Selleck Chemicals (Houston, TX, USA) were dissolved in DMSO. Cycloheximide purchased from Enzo Life Sciences (Farmingdale, NY, USA) was dissolved in distilled water. These reagents were stored at −20°C until use.

Cell viability assay

Cells (5 × 103) were plated in 96‐well culture plates 1 day before treatment. They were then cultured under the indicated conditions and cell viability was measured by MTS assay (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Flow cytometry

Flow cytometry was used for cell cycle analysis and annexin V assay. Cells (1.5 × 105) were plated in 6‐well culture plates 1 day before being treated under the indicated conditions. For cell cycle analysis, the harvested cells were suspended in citrate buffer and stained with propidium iodide. For the annexin V assay, the cells were stained with annexin V and 7‐amino‐actinomycin D (7‐AAD) following the instructions of the manufacturer (Beckman Coulter, Marseille, France). They were then analyzed by a flow cytometer using CellQuest Pro Software (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA).

Western blot analysis

After treatment under the indicated conditions, cells were washed with PBS, suspended in radioimmunoprecipitation (RIPA) buffer, incubated on ice for 15 min, and centrifuged at 20380 g for 12 min. Whole cell lysate was subjected to Western blot analysis as described previously.7 To analyze the expression of ubiquitinated proteins in the detergent‐insoluble fractions (pellets obtained after the protein extraction using RIPA buffer), the pellets were washed with PBS, lysed using Extraction buffer 4 in the WSE‐7421 EzSubcell Extract kit (ATTO, Tokyo, Japan), and then subjected to Western blot analysis. The following antibodies were used: anti‐cyclin D1, anti‐cyclin‐dependent kinase (CDK) 4, anti‐glucose‐regulated protein (GRP) 78, anti‐ubiquitin, anti‐histone deacetylase (HDAC) 1, anti‐HDAC3, and anti‐HDAC6 from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA); anti‐cleaved poly(ADP‐ribose) polymerase (PARP), anti‐HSP70, anti‐endoplasmic reticulum resident protein (ERP) 44, and anti‐endoplasmic oxidoreductin‐1‐like protein (Ero1‐L) from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA, USA); anti‐active caspase 3, anti‐NOXA, and anti‐acetylated histone from Abcam (Cambridge, UK); and anti‐actin from Millipore (Billerica, MA, USA).

Statistical analysis

To evaluate synergism of the combined drugs, combination indexes were calculated by the Chou–Talalay method using CalcuSyn software (Biosoft, Cambridge, UK). The statistical significance of observed differences in cell cycle analysis results and annexin V assay results was determined using the Mann–Whitney U‐test (StatView software; SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). Differences were considered significant at P < 0.05.

Results

Combination of ritonavir and ixazomib inhibited bladder cancer cell viability synergistically

To investigate whether the combination of ritonavir and ixazomib actually kills bladder cancer cells effectively, we first assayed the viability of cells treated for 48 h with the agents alone and in combination (Fig. 1a). Each agent decreased cell viability in a dose‐dependent fashion, but neither agent alone inhibited it completely. When the agents were combined, they exerted a very strong cytotoxicity synergistically under many of the treatment conditions (Table S1). The morphological difference evident after the treatments reflected their interaction: whereas 40 μM ritonavir or 100 nM ixazomib alone had a minimal effect on cell attachment, most of the cells treated with both 40 μM ritonavir and 100 nM ixazomib were floating (Fig. 1b). Thus, the combination of ritonavir and ixazomib was found to inhibit bladder cancer cell viability synergistically.

Figure 1.

Combination of ritonavir and ixazomib inhibited bladder cancer cell viability synergistically. (a) MTS assay. Cells were treated with 20–40 μM ritonavir and/or 20–100 nM ixazomib for 48 h. Data are expressed as mean ± SD; n = 6. (b) Photomicrographs after 48 h of treatment. Note that many of the cells treated with the combination are floating. Original magnification, × 100.

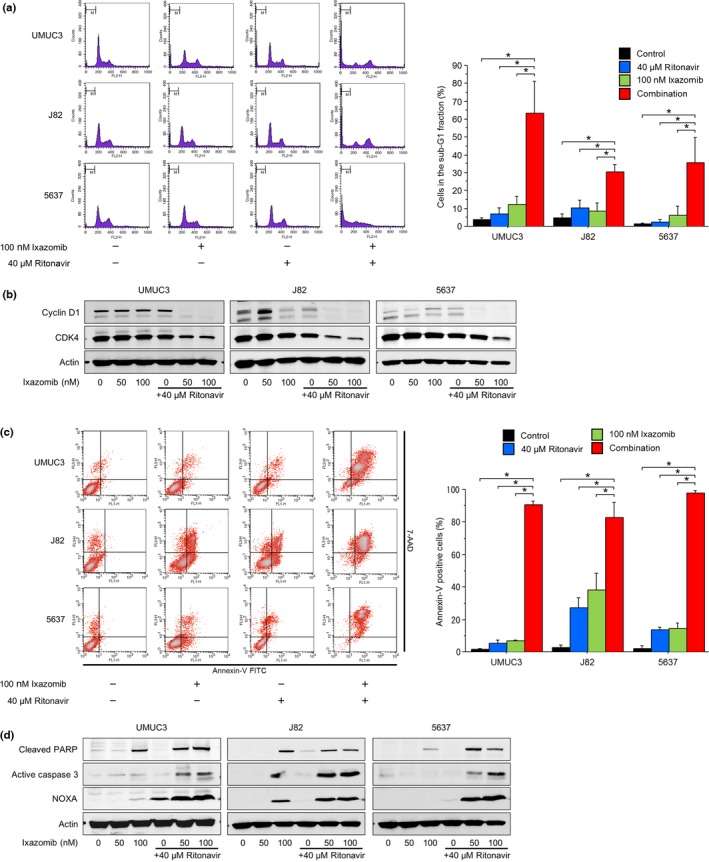

Combination of ritonavir and ixazomib perturbed the cell cycle and induced apoptosis in bladder cancer cells

We then evaluated cell cycle changes caused by 48‐h treatments with ritonavir and ixazomib separately and together (Fig. 2a). Treatment with 40 μM ritonavir or 100 nM ixazomib alone increased the number of cells in the sub‐G1 fraction only slightly, but in combination they increased it significantly, indicative of apoptosis induction. This is consistent with the changes in expression of cyclin D1 and CDK4 (Fig. 2b): 50 and 100 nM ixazomib caused drastic decreases in the expression of these proteins only when combined with 40 μM ritonavir.

Figure 2.

Combination of ritonavir and ixazomib perturbed the cell cycle and induced apoptosis in bladder cancer cells. (a) Cell cycle analysis. Cells were treated for 48 h with 40 μM ritonavir and/or 100 nM ixazomib. Ten thousand cells were counted and changes in the cell cycle were evaluated using flow cytometry. Bar graphs show the percentages of the cells in the sub‐G1 fraction. Data are expressed as mean ± SD from three independent experiments. *P = 0.0495. (b) Western blot analysis for cyclin D1 and cyclin‐dependent kinase (CDK)4. Cells were treated for 48 h with 50 and 100 nM ixazomib with or without 40 μM ritonavir. Actin was used for the loading control. Representative blots are shown. (c) Annexin V assay. Cells were treated for 48 h with 40 μM ritonavir and/or 100 nM ixazomib. Ten thousand cells were counted and apoptotic cells were detected by annexin V assay using flow cytometry. Bar graphs show apoptotic cell percentages. Data are expressed as mean ± SD from three independent experiments. *P = 0.0495. (d) Western blot analysis for cleaved poly(ADP‐ribose) polymerase (PARP), active caspase 3, and NOXA. Cells were treated for 48 h with 50 and 100 nM ixazomib with or without 40 μM ritonavir. Actin was used for the loading control. Representative blots are shown.

To confirm the enhanced induction of apoptosis by the combination, we undertook the annexin V assay and also evaluated changes in the expression of apoptosis‐related proteins. The combination increased the number of annexin‐V positive cells significantly (Fig. 2c). Because the cells were also strongly positive for 7‐AAD, the apoptosis was thought to be accompanied by necrosis (i.e., late apoptosis). Induction of apoptosis was also evidenced by the increased expression of the apoptosis‐related proteins cleaved PARP, active caspase 3, and NOXA (Fig. 2d).

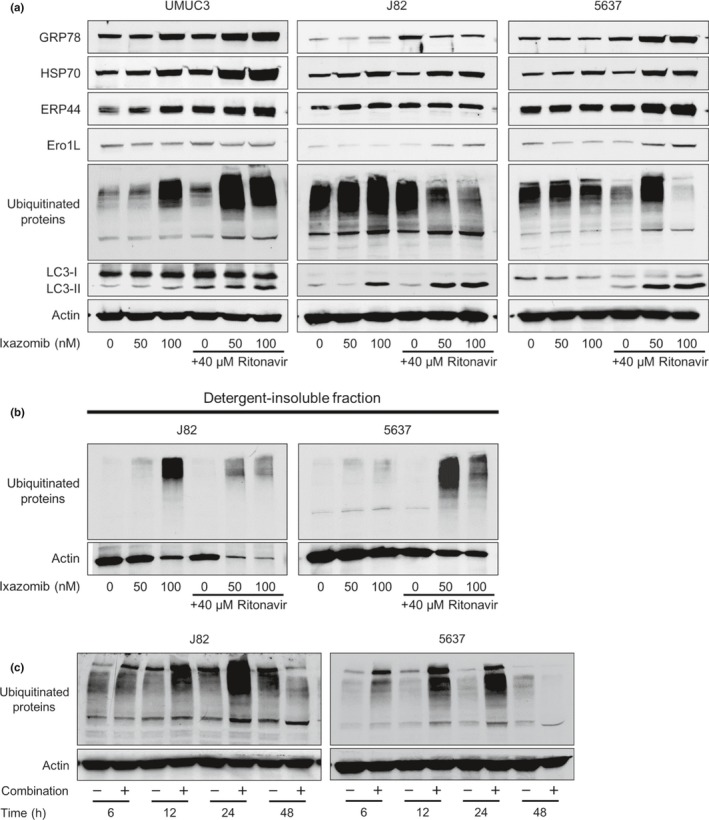

Combination of ritonavir and ixazomib caused ubiquitinated protein accumulation and ER stress in bladder cancer cells

Our hypothesis is that ixazomib inhibits degradation of the ritonavir‐increased ubiquitinated unfolded proteins and thereby causes them to accumulate in the cell. We tested it by treating cells for 48 h with 50 and 100 nM ixazomib with or without 40 μM ritonavir and examining the changes in the expression of ubiquitinated proteins (Fig. 3a). Ritonavir (40 μM) did not cause ubiquitinated protein accumulation in any of the cell lines. In UMUC3 cells, the combination of 40 μM ritonavir and either 50 or 100 nM ixazomib caused marked ubiquitinated protein accumulation as expected. In 5637 cells, 40 μM ritonavir combined with 50 nM ixazomib caused ubiquitinated protein accumulation; however, 40 μM ritonavir combined with 100 nM ixazomib decreased it. In J82 cells, a combination of 40 μM ritonavir and either 50 or 100 nM ixazomib decreased ubiquitinated protein accumulation. The decreased ubiquitinated protein accumulation seen in 5637 and J82 cells is seemingly incompatible with our hypothesis, but because the combination increased the expression of at least one of the ER stress markers GRP78, HSP70, ERP44, and Ero1L in all the cell lines (i.e., the unfolded protein response was induced), unfolded proteins themselves were thought to have accumulated even though the expression of unfolded ubiquitinated proteins seemed to have decreased. We thought this apparent decrease in the expression of ubiquitinated proteins was due to their aggregating and shifting into the detergent‐insoluble fraction, as suggested by Mimnaugh et al.4 The combination also induced autophagy as evidenced by the increased expression of the autophagy marker LC3‐II. This is consistent with an aggregation‐and‐shift process because aggregated proteins are degraded by autophagy.10

Figure 3.

Combination of ritonavir and ixazomib caused ubiquitinated protein accumulation and endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress in bladder cancer cells. (a) Western blot analysis for ER stress markers, ubiquitinated proteins, and an autophagy marker. Cells were treated for 48 h with 50 or 100 nM ixazomib with or without 40 μM ritonavir. Actin was used for the loading control. Representative blots are shown. (b) Western blot analysis for ubiquitinated proteins in detergent‐insoluble fraction. Cells were treated for 48 h with 50 or 100 nM ixazomib with or without 40 μM ritonavir. The detergent‐insoluble fraction was lysed and subjected to Western blotting. Actin was used for the loading control. Representative blots are shown. (c) Western blotting for ubiquitinated proteins. Cells were treated with 40 μM ritonavir and 100 nM ixazomib for 6, 12, 24, and 48 h. Actin was used for the loading control. Representative blots are shown. Ero1‐L, endoplasmic oxidoreductin‐1‐like protein;ERP44, endoplasmic reticulum resident protein 44; GRP78, glucose‐regulated protein 78; HSP70, heat shock protein 70; LC3, light chain 3.

To prove that this aggregation‐and‐shift process occurred in the present study, we lysed the detergent‐insoluble fraction and evaluated the expression of ubiquitinated proteins by using Western blot analysis. Interestingly, in the conditions that caused autophagy as evidenced by the increased expression of LC3‐II, namely, those in which protein aggregation occurred (100 nM ixazomib, 40 μM ritonavir and 50 nM ixazomib, and 40 μM ritonavir and 100 nM ixazomib in J82 cells; 40 μM ritonavir and 50 nM ixazomib, and 40 μM ritonavir and 100 nM ixazomib in 5637 cells; Fig. 3a), the expression of ubiquitinated protein in the detergent‐insoluble fraction actually increased (Fig. 3b). This means that aggregated ubiquitinated proteins shift to the detergent‐insoluble fraction, which accounts for the seemingly decreased ubiquitinated protein accumulation by the combination.

To further explore the mechanism of the decreased expression of ubiquitinated proteins in J82 and 5637 cells, we treated these cells with 40 μM ritonavir and 100 nM ixazomib for 6, 12, 24, and 48 h and examined the changes in the expression of ubiquitinated proteins (Fig. 3c). In this experiment, the expression of ubiquitinated proteins was increased by the combination in a time‐dependent fashion up to 24 h and then decreased at 48 h. This also suggests that the combination of ritonavir and ixazomib caused ubiquitinated protein accumulation in a time‐dependent fashion and, when the ubiquitinated proteins were excessively accumulated (i.e., after 48 h) they aggregated and shifted into the detergent‐insoluble fraction.

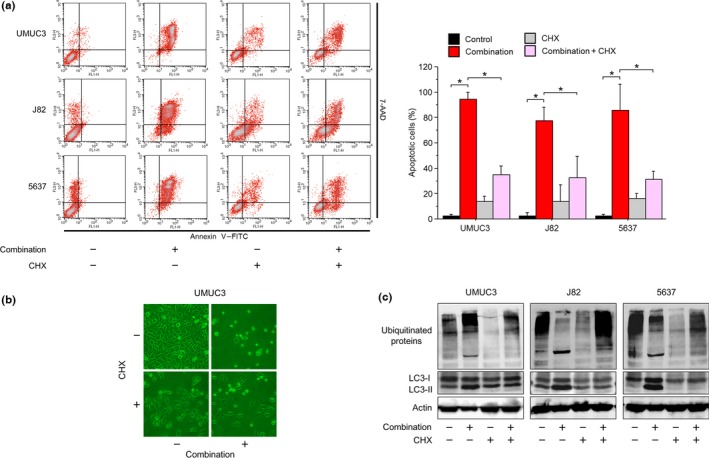

Accumulation of ubiquitinated proteins was important for the combination's anticancer action

To investigate whether the accumulation of ubiquitinated proteins itself was important for the combination's action, we then evaluated changes in the combination's efficacy under protein synthesis inhibition. We postulated that if accumulation of ubiquitinated proteins were important for the combination's activity, decreasing the combination‐caused ubiquitinated protein accumulation by inhibiting protein synthesis would attenuate the combination's activity. According to the annexin V assay, the combination‐induced apoptosis was markedly attenuated by co‐treatment with 5 μg/mL cycloheximide (Fig. 4a). This attenuation was also reflected in the morphological changes after treatment (Fig. 4b). Protein synthesis was thus thought to be important for the combination's anticancer action.

Figure 4.

Accumulation of ubiquitinated proteins was important for the anticancer action of ritonavir and ixazomib. (a) Annexin V assay. Cells were treated for 48 h with 40 μM ritonavir and 100 nM ixazomib with or without 5 μg/mL cycloheximide (CHX). Ten thousand cells were counted and apoptotic cells were detected by annexin V assay using flow cytometry. Bar graphs show apoptotic cell percentages. Data are expressed as mean ± SD from three independent experiments. *P = 0.0495. (b) Photomicrographs of UMUC3 cells after 48 h of treatment with the combination of 40 μM ritonavir and 100 nM ixazomib with or without 5 μg/mL CHX. Original magnification, ×100. (c) Western blot analysis for ubiquitinated proteins and light chain 3 (LC3). Cells were treated for 48 h with 40 μM ritonavir and 100 nM ixazomib with or without 5 μg/mL CHX. Actin was used for the loading control. Representative blots are shown. 7‐AAD, 7‐amino‐actinomycin D.

We next analyzed changes in the expression of ubiquitinated proteins after 48 h of treatment with the combination with or without 5 μg/mL cycloheximide (Fig. 4c). In UMUC3 cells, the combination increased the expression of ubiquitinated proteins, which was in accordance with the previous experiment, and their increased expression was decreased by the co‐treatment with cycloheximide. This means that inhibiting protein synthesis in these cells decreased the accumulation of ubiquitinated proteins. In J82 and 5637 cells, however, the combination‐decreased expression of ubiquitinated proteins was increased by cycloheximide. This means that, in those cells, cycloheximide kept ubiquitinated proteins from accumulating excessively and therefore the process of aggregating and shifting to the detergent‐insoluble fraction was attenuated. The combination‐increased expression of LC3‐II was decreased by cycloheximide. This is also consistent with cancer cells degrading the combination‐increased aggregations of unfolded proteins by autophagy.

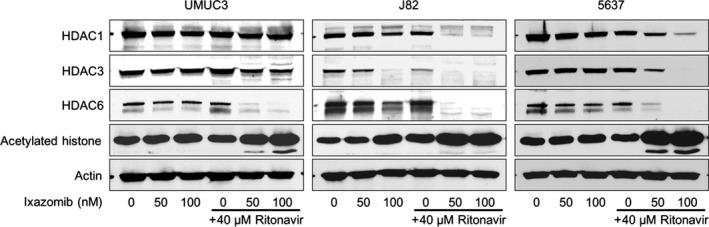

Combination of ritonavir and ixazomib decreased HDAC expression and induced histone acetylation

Because we have shown that ER stress‐inducing combination therapy in prostate cancer cells also induced histone acetylation,7 we hypothesized that the combination of ritonavir and ixazomib might also induce histone acetylation in bladder cancer cells. As expected, the combination induced histone acetylation. In UMUC3 and 5637 cells, neither 50 nM ixazomib nor 100 nM ixazomib alone caused histone acetylation, whereas in J82 cells, 100 nM ixazomib did. In combination with 40 μM ritonavir, however, both 50 and 100 nM ixazomib markedly induced histone acetylation in all three cell lines (Fig. 5). Interestingly, we also found that the expression of HDAC1, 3, and 6 in J82 and 5637 cells and that of HDAC3 and 6 in UMUC3 cells were markedly decreased by the combination, which would in part explain the combination‐induced histone acetylation.

Figure 5.

Combination of ritonavir and ixazomib induced histone acetylation in bladder cancer cells. Western blot analysis for histone deacetylase (HDAC)1, 3, and 6 and acetylated histone. Cells were treated for 48 h with 50 or 100 nM ixazomib with or without 40 μM ritonavir. Actin was used for the loading control. Representative blots are shown.

Discussion

There is no curative treatment for advanced bladder cancer, and a new treatment approach is urgently needed. Inducing ubiquitinated protein accumulation and ER stress is a novel strategy for treating cancer.2 The accumulation of ubiquitinated proteins has been reported to be noxious to tumor cells.4 These accumulated unfolded proteins cause ER stress that induces the expression and post‐transcriptional modification of factors associated with cell death.11 Because inducing ubiquitinated protein accumulation and ER stress thus acts in a way that is different from the non‐curative treatments currently used against advanced bladder cancer, such as a cisplatin–gemcitabine regimen,1 we suggest that it could be a novel approach to treating advanced bladder cancer. In the present study, we investigated the efficacy of a combination of the HIV protease inhibitor ritonavir and the proteasome inhibitor ixazomib by using bladder cancer cells.

The amount of ubiquitinated proteins in a cell is thought to depend on the functions of both molecular chaperones and proteasomes. In UMUC3 cells, 100 nM ixazomib induced ubiquitinated protein accumulation, whereas 50 nM ixazomib did not. The dose of 100 nM ixazomib is thought to have inhibited proteasome function to the extent that the proteasome could not degrade all the unfolded proteins. Inhibition of the proteasome by 50 nM ixazomib, however, seems to have been insufficient and therefore many of the unfolded proteins were degraded. In contrast, in combination with 40 μM ritonavir, both concentrations of ixazomib caused marked ubiquitinated protein accumulation. This is consistent with the previous report that ritonavir inhibits HSP90,8 and the consequently increased amount of unfolded proteins is thought to overwhelm the proteasomes degrading them. In 5637 cells, 40 μM ritonavir combined with 50 nM ixazomib caused ubiquitinated protein accumulation, but combined with 100 nM ixazomib it decreased the amount of ubiquitinated proteins. Furthermore, in J82 cells, 40 μM ritonavir combined with either 50 or 100 nM ixazomib decreased the amount of ubiquitinated proteins. This result seems to be inconsistent with our hypothesis that inhibition of both molecular chaperones and proteasomes causes ubiquitinated protein accumulation. However, Mimnaugh et al.4 reported that the combination of the HSP90 inhibitor geldanamycin and the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib decreased the amount of ubiquitinated proteins in the detergent‐soluble fraction because it caused them to aggregate and shift into the detergent‐insoluble fraction. This shift also occurred in the experiments in our study: the increased expression of ER stress markers means that the combination actually increased the amount of unfolded proteins, and the induction of autophagy is consistent with protein aggregation because aggregated proteins are cleared by autophagy.10 Furthermore, we have shown that the treatment conditions causing autophagy, namely, those in which aggregation occurred, actually increased the expression of ubiquitinated proteins in the detergent‐insoluble fraction, demonstrating the aggregation‐and‐shift process caused by the combination. Paradoxically, conditions that caused more ubiquitinated protein accumulation did not necessarily cause more accumulation in the detergent‐insoluble fraction; for example, in J82 cells, the combinations caused less ubiquitinated protein accumulation in the detergent‐insoluble fraction than 100 nM ixazomib alone did. Similarly, in 5637 cells, 40 μM ritonavir and 100 nM ixazomib increased the amount of ubiquitinated protein in the detergent‐insoluble fraction less than 40 μM ritonavir and 50 nM ixazomib did. This might be explained by protein synthesis inhibition due to extensive ER stress,12 but further study is needed to clarify the exact mechanism of this phenomenon.

To our knowledge, why this shift of ubiquitinated proteins occurs has not yet been clarified. In 5637 cells, 40 μM ritonavir combined with 50 nM ixazomib increased the expression of ubiquitinated proteins, but combined with 100 nM ixazomib, decreased it. This means that further inhibition of protein degradation, namely, further accumulation of ubiquitinated proteins, caused their shift to the insoluble fraction. Our time course study using J82 and 5637 cells showed that the combination increased the expression of ubiquitinated proteins for the first 24 h but decreased it after 48 h. This also could mean that the amount of ubiquitinated proteins accumulated determines whether they shift to the insoluble fraction. Furthermore, in these cell lines, inhibiting protein synthesis by adding cycloheximide increased the expression of ubiquitinated proteins, which the combination alone decreased. Thus, whether ubiquitinated proteins shift to the insoluble fraction seems to depend on their degree of accumulation in the cell.

Histone acetylation could be another important mechanism of action for the combination of ritonavir and ixazomib. Histone acetylation and deacetylation are associated with tumorigenesis and the progression of malignancy, and causing histone acetylation (e.g., by using histone deacetylase inhibitors) has emerged as a novel cancer therapy.13, 14 Furthermore, in clinically obtained bladder cancer specimens, histone acetylation status was demonstrated to be decreased and to be lower in muscle‐invasive cancer than non‐muscle‐invasive cancer.15 Inducing histone acetylation is therefore thought to be another attractive way to inhibit bladder cancer growth. Interestingly, we found that the ritonavir–ixazomib combination decreased the expression of HDACs, which might in part explain the histone acetylation caused by the combination. The inhibition of HDAC6 expression is of great interest for reasons other than its role in inducing histone acetylation because HDAC6 inhibition has been reported to induce hyperacetylation of HSP90, leading to suppression of its chaperone function.16, 17 Therefore, the inhibition of HDAC6 expression by the combination might further suppress the HSP90 function, thereby enhancing the combination's ability to cause ubiquitinated protein accumulation. Thus, the combination‐induced ER stress might start a vicious circle of HSP90 suppression and HDAC6 inhibition in cancer cells.

The antiproliferative activity of the combination of ritonavir and ixazomib seems to be due, at least in part, to the accumulation of ubiquitinated proteins and the consequent induction of ER stress. Inhibition of protein synthesis suppressed the accumulation of ubiquitinated proteins and attenuated the ability of the combination to kill bladder cancer cells. The combination decreased the expression of cyclin D1 and CDK4, which was in accordance with the induction of ER stress and histone acetylation, because their expression has been shown to be inhibited by both the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib18, 19 and the HDAC inhibitor vorinostat.20 The combination‐increased expression of NOXA, a novel pro‐apoptotic BH3‐only protein that is activated by ER stress,21 is also evidence that the combination‐induced apoptosis was a consequence of ER stress induction.

One limitation of the present study is that the efficacy of the combination has not been evaluated in animal models. However, the combination would likely be effective in them because combinations causing ubiquitinated protein accumulation or ER stress were reportedly effective in suppressing tumor growth in animal models of other types of cancer.5, 6, 7 The next step toward application of the combination should be animal experiments evaluating side‐effects and determining the optimal dosage.

There are also limitations to applying this combination clinically. One is that ritonavir is a potent cytochrome P450 inhibitor.22 In clinical settings, it could increase the serum concentration of ixazomib by inhibiting its degradation by the liver and therefore increasing its side‐effects. Another is that drug‐induced ER stress has been reported to be associated with adverse effects23 and the safety of inducing robust ER stress is unclear. However, the strategy of inducing ER stress could be applied clinically by carefully undertaking a phase I trial. The vorinostat–bortezomib combination was shown to induce robust ER stress7 but has been proven to be safe to be given to patients.24, 25, 26, 27

In clinical settings, response to the combination of ritonavir and ixazomib may differ among the patients. Therefore, finding biomarkers that predict the combination's efficacy would be helpful in selecting the patients who would most benefit from its use. Recently, in terms of HSP90 suppression, Acquaviva et al.28 suggested that UDP‐glucuronosyltransferase enzyme expression may be a predictive factor for clinical response to resorcinol‐based HSP90 inhibitors. Exploring such biomarkers for the combination of ritonavir and ixazomib would also be an important next step.

In conclusion, we have shown for the first time that the combination of ritonavir and ixazomib kills bladder cancer cells by causing ubiquitinated protein accumulation and ER stress. The present study provides a theoretical basis for future development of novel ubiquitinated‐protein‐accumulation‐based therapies effective against bladder cancer.

Disclosure Statement

The authors have no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

Table S1. Combination indexes.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science KAKENHI Grant No. JP26462434.

Cancer Sci 108 (2017) 1194–1202

Funding Information

Japan Society for the Promotion of Science.

References

- 1. von der Maase H, Sengelov L, Roberts JT et al Long‐term survival results of a randomized trial comparing gemcitabine plus cisplatin, with methotrexate, vinblastine, doxorubicin, plus cisplatin in patients with bladder cancer. J Clin Oncol 2005; 23: 4602–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Liu Y, Ye Y. Proteostasis regulation at the endoplasmic reticulum: a new perturbation site for targeted cancer therapy. Cell Res 2011; 21: 867–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Naujokat C, Hoffmann S. Role and function of the 26S proteasome in proliferation and apoptosis. Lab Invest 2002; 82: 965–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mimnaugh EG, Xu W, Vos M et al Simultaneous inhibition of hsp 90 and the proteasome promotes protein ubiquitination, causes endoplasmic reticulum‐derived cytosolic vacuolization, and enhances antitumor activity. Mol Cancer Ther 2004; 3: 551–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sato A, Asano T, Isono M, Ito K, Asano T. Panobinostat synergizes with bortezomib to induce endoplasmic reticulum stress and ubiquitinated protein accumulation in renal cancer cells. BMC Urol 2014; 71: 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sato A, Asano T, Ito K, Asano T. Ritonavir interacts with bortezomib to enhance protein ubiquitination and histone acetylation synergistically in renal cancer cells. Urology 2012; 79: 966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sato A, Asano T, Ito K, Asano T. Vorinostat and bortezomib synergistically cause ubiquitinated protein accumulation in prostate cancer cells. J Urol 2012; 188: 2410–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Srirangam A, Mitra R, Wang M et al Effects of HIV protease inhibitor ritonavir on Akt‐regulated cell proliferation in breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2006; 12: 1883–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kumar SK, LaPlant B, Roy V et al Phase 2 trial of ixazomib in patients with relapsed multiple myeloma not refractory to bortezomib. Blood Cancer J 2015; 5: e338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mizushima N. The role of mammalian autophagy in protein metabolism. Proc Jpn Acad Ser B Phys Biol Sci 2007; 83: 39–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Di Fazio P, Ocker M, Montalbano R. New drugs, old fashioned ways: ER stress induced cell death. Curr Pharm Biotechnol 2012; 13: 2228–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Paschen W. Shutdown of translation: lethal or protective? Unfolded protein response versus apoptosis. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2003; 23: 773–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Olzscha H, Bekheet ME, Sheikh S, La Thangue NB. HDAC Inhibitors. Methods Mol Biol 2016; 1436: 281–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sato A. Vorinostat approved in Japan for treatment of cutaneous T‐cell lymphomas: status and prospects. Onco Targets Ther 2012; 5: 67–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ellinger J, Schneider AC, Bachmann A, Kristiansen G, Müller SC, Rogenhofer S. Evaluation of global histone acetylation levels in bladder cancer patients. Anticancer Res 2016; 36: 3961–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bali P, Pranpat M, Bradner J et al Inhibition of histone deacetylase 6 acetylates and disrupts the chaperone function of heat shock protein 90: a novel basis for antileukemia activity of histone deacetylase inhibitors. J Biol Chem 2005; 280: 26729–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Fiskus W, Ren Y, Mohapatra A et al Hydroxamic acid analogue histone deacetylase inhibitors attenuate estrogen receptor‐alpha levels and transcriptional activity: a result of hyperacetylation and inhibition of chaperone function of heat shock protein 90. Clin Cancer Res 2007; 13: 4882–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Yin D, Zhou H, Kumagai T et al Proteasome inhibitor PS‐341 causes cell growth arrest and apoptosis in human glioblastoma multiforme (GBM). Oncogene 2005; 24: 344–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Pham LV, Tamayo AT, Yoshimura LC, Lo P, Ford RJ. Inhibition of constitutive NF‐kappa B activation in mantle cell lymphoma B cells leads to induction of cell cycle arrest and apoptosis. J Immunol 2003; 171: 88–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Yin D, Ong JM, Hu J et al Suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid, a histone deacetylase inhibitor: effects on gene expression and growth of glioma cells in vitro and in vivo. Clin Cancer Res 2007; 13: 1045–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Li J, Lee B, Lee AS. Endoplasmic reticulum stress‐induced apoptosis: multiple pathways and activation of p53‐up‐regulated modulator of apoptosis (PUMA) and NOXA by p53. J Biol Chem 2006; 281: 7260–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Eagling VA, Back DJ, Barry MG. Differential inhibition of cytochrome P450 isoforms by the protease inhibitors, ritonavir, saquinavir and indinavir. Br J Clin Pharmacol 1997; 44: 190–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Foufelle F, Fromenty B. Role of endoplasmic reticulum stress in drug‐induced toxicity. Pharmacol Res Perspect 2016; 4: e00211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Badros A, Burger AM, Philip S et al Phase I study of vorinostat in combination with bortezomib for relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma. Clin Cancer Res 2009; 15: 5250–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Friday BB, Anderson SK, Buckner J et al Phase II trial of vorinostat in combination with bortezomib in recurrent glioblastoma: a north central cancer treatment group study. Neuro Oncol 2012; 14: 215–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Muscal JA, Thompson PA, Horton TM et al A phase I trial of vorinostat and bortezomib in children with refractory or recurrent solid tumors: a Children's Oncology Group phase I consortium study (ADVL0916). Pediatr Blood Cancer 2013; 60: 390–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Deming DA, Ninan J, Bailey HH et al A Phase I study of intermittently dosed vorinostat in combination with bortezomib in patients with advanced solid tumors. Invest New Drugs 2014; 32: 323–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Acquaviva J, He S, Zhang C et al FGFR3 translocations in bladder cancer: differential sensitivity to HSP90 inhibition based on drug metabolism. Mol Cancer Res 2014; 12: 1042–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Combination indexes.