Abstract

Background

Cassava brown streak disease is emerging as the most important viral disease of cassava in Africa, and is consequently a threat to food security. Two distinct species of the genus Ipomovirus (family Potyviridae) cause the disease: Cassava brown streak virus (CBSV) and Ugandan cassava brown streak virus (UCBSV). To understand the evolutionary relationships among the viruses, 64 nucleotide sequences from the variable P1 gene from major cassava producing areas of east and central-southern Africa were determined.

Methods

We sequenced an amplicon of the P1 region of 31 isolates from Malawi and Tanzania. In addition to these, 33 previously reported sequences of virus isolates from Uganda, Kenya, Tanzania, Malawi and Mozambique were added to the analysis.

Results

Phylogenetic analyses revealed three major P1 clades of Cassava brown streak viruses (CBSVs): in addition to a clade of most CBSV and a clade containing all UCBSV, a novel, intermediate clade of CBSV isolates which has been tentatively called CBSV-Tanzania (CBSV-TZ). Virus isolates of the distinctive CBSV-TZ had nucleotide identities as low as 63.2 and 63.7% with other members of CBSV and UCBSV respectively.

Conclusions

Grouping of P1 gene sequences indicated for distinct sub-populations of CBSV, but not UCBSV. Representatives of all three clades were found in both Tanzania and Malawi.

Keywords: Cassava brown streak viruses, Evolution, Diversity

Background

Cassava (Manihot esculenta Crantz, Family: Euphorbiaceae) is an important staple food crop for over 800 million people across the globe [1]. Although cassava is known to be vulnerable to at least 20 different viruses, the two most economically damaging viral diseases in Africa are cassava mosaic disease and cassava brown streak disease (CBSD). The diseases have been associated with production losses worth more than US$1 billion every year [2]. Recent developments in cassava research have shown that CBSD is emerging as the most important viral disease of cassava in Africa, and is consequently a threat to food security [1]. Two distinct species of the genus Ipomovirus (family Potyviridae), Cassava brown streak virus [3] and Ugandan cassava brown streak virus (UCBSV [4, 5]) cause the disease. In this paper, both viruses are collectively called CBSVs. The characteristic symptoms of CBSVs include typical ‘feathery’ chlorosis and yellow patch symptoms along secondary and tertiary veins of older leaves of cassava, brown streaks on the stems, constriction in storage roots, and brown spots in the tuber visible when it is cut [6, 7]. Previously, CBSD was reported only from the coastal lowlands of East Africa, but recently it has spread throughout the Great Lakes region of East and Central-Southern Africa [8–14].

Potyviridae is a family of plant viruses with a single stranded, positive sense RNA genome and flexious, filamentous particles [10]. The monopartite +ssRNA genomes of the members of Potyviridae share similar genomic organization, with levels of amino acid identity in their polyproteins ranging from 42 to 56% among different species of the same genus and from 25 to 33% among viruses from different genera [11]. However, conservation of individual mature proteins varies. P1, a serine protease that self-cleaves at its C terminus and acts as an accessory factor for genome amplification (reviewed in [12] is the first protein of the polyprotein and the most variable in length and amino acid sequence [11]. Other roles of P1 include boosting the activity of the helper component protease (HCPro) to suppress RNA silencing [13] and to enhance the pathogenicity of heterologous plant viruses during coinfection [14, 15]. The genomes of CBSVs lack HCPro and the short P1 gene has RNA silencing suppression function [16]. Significantly divergent P1 gene sequences of CBSV have been found and recent studies have suggested that the P1 gene of CBSV (together with NIa, 6 K2, and NIb) have evolved more rapidly compared to other genes [17].

Genetic variability is an intrinsic feature of RNA viruses because of high mutation rates resulting from the lack of proofreading activity of their RNA-dependent RNA polymerases [14, 18]. RNA recombination events can additionally shape the diversity of populations of RNA viruses [15] which can lead to new phenotypes such as host range expansion [19]. Diversity among CBSV isolates was initially assessed using sequences at the conserved 3′-terminus of the RNA genome comprising the coat protein gene and parts of NIb [16] while comparative studies with complete viral genomes [5, 9, 20], have revealed more pronounced and distinctive features among virus isolates. In one previous study [5], sequence analysis of 7 virus isolates revealed two distinct CBSV sequence clades that were separated to the species level. Different biological features of members of these two clades provided justification for CBSVs to be assigned to two species: UCBSV and CBSV [5]. In that same study an isolate from coastal Tanzania (CBSV-Tan70, FN434473) was identified which was very similar to CBSV isolates throughout much of its genome, but with a strikingly different P1 gene which was equidistantly related to both CBSV and UCBSV isolates. As this divergent P1 region was found only in one CBSV isolate which otherwise had similar biological features than other CBSVs, further species delineation was not possible because of lack of similar isolates. The recent analyses of additional CBSV genome sequences from Tanzania [9] and from Uganda [16] revealed further diversity and also indicate the potential for an additional species or subspecies within the CBSVs.

In the study presented here, a total of 64 P1 gene sequences of CBSV isolates from major cassava producing areas of east and central-southern Africa were analysed. We sequenced a portion of the P1 gene from 31 isolates (from Malawi and Tanzania) and analyzed them with those previously reported from Uganda, Kenya, Tanzania, Malawi and Mozambique and present substantial evidence for the widespread occurrence of a distinct Cassava brown streak virus clade tentatively named CBSV-Tanzania (CBSV-TZ).

Methods

Source of virus isolates, amplification and sequencing

Cassava cuttings collected from CBSD-symptomatic plants in Malawi and Tanzania (Table 1) during national surveys in 2013 (under the auspices of each country’s agricultural research institutes). The plants were classified by having symptoms that were consistent with CBSD (feathery chlorosis along veins in leaves and brown streaks/lesions along the plant stem), or potentially were coinfected with agents causing both CBSD and CMD (mosaic, mottling, misshapen and twisted leaflets) and were taken to The Leibniz Institute – Deutsche Sammlung von Mikroorganismen and Zellkulturen GmbH (DSMZ) Plant Virus Department, where they were maintained under greenhouse conditions. Total RNA was extracted from the virus-infected leaves of the cassava plants using the cetyl trimethyl ammonium bromide method [21] with modifications described previously [22] or using an RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen). Nucleic acids were quantified using a Nanodrop spectrophotometer, and about 2.0 × 10−5 μg/mL nucleic acid was used for virus detection by RT-PCR as detailed in Winter et al. [5]. A cDNA fragment, the partial sequence of the P1 gene, was amplified using virus specific primer sets designed by Winter et al. [5]. The reactions were performed in a GeneAmp 9700 PCR thermal cycler (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) set with the following conditions: 42 °C for 30 min for reverse transcription, followed by heat denaturation at 94 °C for 5 min; and then 35 cycles of amplification comprising the following: denaturation at 94 °C for 1 min, annealing at 52 °C for 1 min, extension at 72 °C for 1 min, followed by a single cycle of final extension at 72 °C for 10 min. All RT-PCR products were purified using a Qiagen gel extraction kit, ligated into the pDrive U/A cloning vector (Qiagen) and subsequently electroporated into Escherichia coli DH5α cells. The clones were Sanger sequenced in both orientations. A single consensus sequence for each isolate was verified to be CBSV by blastn searches of GenBank (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi). The resulting nucleotide sequences were submitted to GenBank (pending accession numbers, Table 1).

Table 1.

Cassava brown streak isolates used in this study

| Isolate name | Location | Symptoms | Year collected | Country | Accession number | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TZ_Chamb_1_13 | Chambezi | CBSD-like | 2013 | Tanzania | KY290016 | This study |

| TZ_Chamb_2_13 | Chambezi | CBSD-like | 2013 | Tanzania | KY290017 | This study |

| TZ_Chamb_3_13 | Chambezi | CBSD-like | 2013 | Tanzania | KY290018 | This study |

| TZ_Chamb_4_13 | Chambezi | CBSD-like | 2013 | Tanzania | KY290019 | This study |

| TZ_Chamb_5_13 | Chambezi | CBSD-like | 2013 | Tanzania | KY290010 | This study |

| TZ_Chamb_6_13 | Chambezi | CBSD-like | 2013 | Tanzania | KY290011 | This study |

| TZ_Chamb_7_13 | Chambezi | CBSD-like | 2013 | Tanzania | KY290020 | This study |

| TZ_Chamb_8_13 | Chambezi | CBSD-like | 2013 | Tanzania | KY290012 | This study |

| TZ_Chamb_9_13 | Chambezi | CBSD-like | 2013 | Tanzania | KY290013 | This study |

| TZ_Chamb_10_13 | Chambezi | CBSD-like | 2013 | Tanzania | KY290014 | This study |

| TZ_Chamb_11_13 | Chambezi | CBSD-like | 2013 | Tanzania | KY290015 | This study |

| TZ_Chamb_12_13 | Chambezi | CBSD-like | 2013 | Tanzania | KY290021 | This study |

| TZ_Chamb_13_13 | Chambezi | CBSD-like | 2013 | Tanzania | KY290022 | This study |

| TZ_Chamb_14_13 | Chambezi | CBSD-like | 2013 | Tanzania | KY290023 | This study |

| TZ_Unguja_1_13 | Unguja | CBSD-like | 2013 | Tanzania | KY290024 | This study |

| TZ_Mari_1_13 | MARI | CBSD-like | 2013 | Tanzania | KY290025 | This study |

| MW07 | Karonga | CBSD-like | 2013 | Malawi | KY290003 | This study |

| MW08 | Karonga | CBSD-like | 2013 | Malawi | KY290004 | This study |

| MW12 | Karonga | CBSD-like | 2013 | Malawi | KY289996 | This study |

| MW13 | Karonga | CBSD-like | 2013 | Malawi | KY290006 | This study |

| MW14 | Rumphi | CBSD-like | 2013 | Malawi | KY289999 | This study |

| MW15 | Karonga | CBSD-like | 2013 | Malawi | KY289998 | This study |

| MW16 | NkhataBay | CBSD-like | 2013 | Malawi | KY289995 | This study |

| MW22 | Karonga | CBSD-like | 2013 | Malawi | KY290001 | This study |

| MW23 | Karonga | CBSD-like | 2013 | Malawi | KY290000 | This study |

| MW37 | NkhataBay | CBSD + CMD | 2013 | Malawi | KY290008 | This study |

| MW40 | Nkhotakota | CBSD-like | 2013 | Malawi | KY290002 | This study |

| MW42 | Karonga | CBSD-like | 2013 | Malawi | KY290005 | This study |

| MW43 | NkhataBay | CBSD-like | 2013 | Malawi | KY290007 | This study |

| MW46 | Lilongwe | CBSD + CMD | 2013 | Malawi | KY289997 | This study |

| MW50 | NkhataBay | CBSD-like | 2013 | Malawi | KY290009 | This study |

| TZ-Nal:07 | Naliendele | – | 2007 | Tanzania | HG965221 | Bayene et al., unpublished |

| TZ:Kor6:08 | Unknown | – | 2008 | Tanzania | GU563327 | Mbanzibwa et al., 2011 [33] |

| TanZ | Kiabakari, Musoma | – | 2008 | Tanzania | GQ329864 | Monger et al., 2010 [34] |

| Tan70 | Mlandizi | – | 2009 | Tanzania | FN434437 | Winter et al., 2010 [5] |

| MLB3 | Muleba | – | 2008 | Tanzania | FJ039520 | Mbanziwa et al., 2011 [33] |

| CBSV-Ug | Unknown | – | 2006 | Uganda | FJ185044 | Monger et al., 2010 [34] |

| Mo_83 | Namacurra | – | 2009 | Mozambique | FN434436 | Winter et al., 2010 [5] |

| Ke_125 | Kilifi | – | 1999 | Kenya | FN433930 | Winter et al., 2010 [5] |

| Ke_54 | Kilifi | – | 1999 | Kenya | FN433931 | Winter et al., 2010 [5] |

| UGKab07 | Kabanyolo | – | 2007 | Uganda | HG965222 | Bayene, et al., unpublished |

| Ma_42 | Chitedze | – | 2007 | Malawi | FN433932 | Winter et al., 2010 [5] |

| Ma_43 | Salima | – | 2007 | Malawi | FN433933 | Winter et al., 2010 [5] |

| TZ:Ser 5 | Serengeti | – | 2013 | Tanzania | KR108838 | Ndunguru et al., 2015 [9] |

| UCBSV_TZ:Ser 6 | Serengeti | – | 2013 | Tanzania | KR108837 | Ndunguru et al., 2015 [9] |

| CBSV_TZ:Ser 6 | Serengeti | – | 2013 | Tanzania | KR108830 | Ndunguru et al., 2015 [9] |

| TZ-Tan 19-1 | Tanga | – | 2013 | Tanzania | KR108834 | Ndunguru et al., 2015 [9] |

| TZ-Tan 19-2 | Tanga | – | 2013 | Tanzania | KR108832 | Ndunguru et al., 2015 [9] |

| TZ-Tan 23 | Tanga | – | 2013 | Tanzania | KR108839 | Ndunguru et al., 2015 [9] |

| TZ-Tan 26 | Tanga | – | 2013 | Tanzania | KR108833 | Ndunguru et al., 2015 [9] |

| TZ-Nya 36 | Nyasa | – | 2013 | Tanzania | KR108831 | Ndunguru et al., 2015 [9] |

| TZ-Nya 38 | Nyasa | – | 2013 | Tanzania | KR108829 | Ndunguru et al., 2015 [9] |

| TZ-Mf-49 | Mafia | – | 2013 | Tanzania | KR108828 | Ndunguru et al., 2015 [9] |

| TZ-Maf-51 | Mafia | – | 2013 | Tanzania | KR108836 | Ndunguru et al., 2015 [9] |

| TZ-Maf-58 | Mafia | – | 2013 | Tanzania | KR108835 | Ndunguru et al., 2015 [9] |

| F21S4_S11_N | Unknown | – | 2013 | Kenya | KR911736 | Kathurima et al., 2016 [32] |

| F25S6_S10_N | Unknown | – | 2013 | Kenya | KR911725 | Kathurima et al., 2016 [32] |

| F3S1_S23_C | Unknown | – | 2013 | Kenya | KR911727 | Kathurima et al., 2016 [32] |

| F16S4_S7_W | Unknown | – | 2013 | Kenya | KR911723 | Kathurima et al., 2016 [32] |

| F18S1_S3_W | Unknown | – | 2013 | Kenya | KR911726 | Kathurima et al., 2016 [32] |

| F10S2_S20_C | Unknown | – | 2013 | Kenya | KR911722 | Kathurima et al., 2016 [32] |

| F9S2_S21_C | Unknown | – | 2013 | Kenya | KR911721 | Kathurima et al., 2016 [32] |

| F17S3_S2 | Unknown | – | 2013 | Kenya | KR911724 | Kathurima et al., 2016 [32] |

| F19SS2_S4_W | Unknown | – | 2013 | Kenya | KR911729 | Kathurima et al.,2016 [32] |

Nucleotide similarity and putative recombination breakpoint analysis

Percentage nucleotide identities were computed in Geneious Software v10.0.5 [23]. A matrix of nucleotide identities was produced using the Sequence Demarcation Tool v1 [24]. Putative recombination events were detected using nine recombination detection programs within the RDP4 package (http://darwin.uvigo.es/rdp/rdp.html): RDP, GENECONV, MaxChi, Chimaera, Bootscan, Siscan, PhylPor, LARD, and 3Seq [25]. Analyses were carried out using default settings (except sequences were set to linear) and the Bonferroni correction P-value cut-off of 0.05. Only breakpoints supported by at least three methods were considered further [26].

Phylogenetic analysis

Phylogenetic relationship among P1 regions of CBSV isolates (Table 1) was determined. The sequences were aligned using ClustalW [27] in MEGA 7 [28] and edited manually. The alignment was trimmed to give all sequences uniform length. MEGA 7 was used to construct maximum likelihood (ML) phylogenetic trees, and editing was done in FigTree v1.4.2 (http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree/). The trees were created using a GTR nucleotide substitution model, and the best tree was bootstrapped with 1000 replicates [29].

Results

To examine the genetic diversity of CBSVs, field surveys and extensive sampling were performed in Malawi and Tanzania in 2013, yielding a total of 31 newly sequenced isolates (16 from Tanzania and 15 from Malawi). Thirty-three other previously published P1 sequences of CBSVs were retrieved from GenBank and aligned with these new sequences and a sister taxon, Sweet potato mild mottle virus [3]. The alignment (510 nt) was found to be free of detectable recombination.

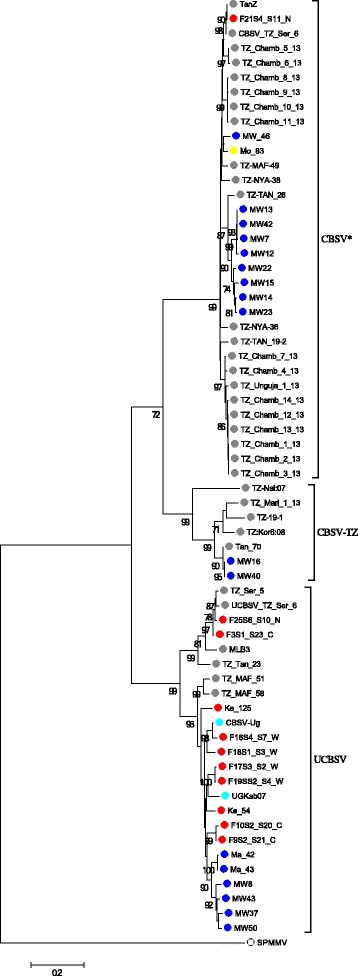

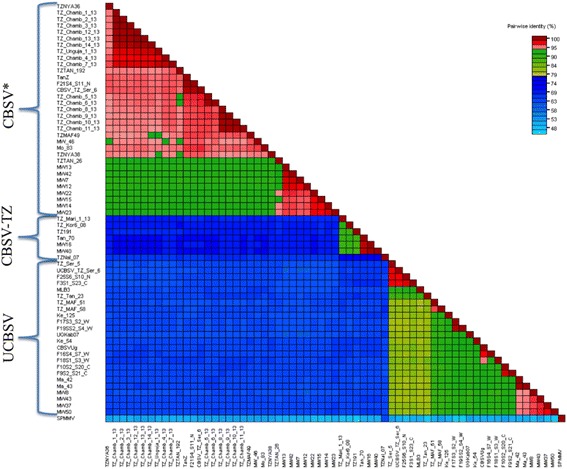

A phylogenetic tree generated from these 64 partial P1 sequences confirmed significant genetic variability among CBSVs and unambiguously resolved three clades. Seven isolates; five from Tanzania (TZ-Nal:07, TZ_Mari_1_13, TZ:Kor6:08, TZ-19-1, Tan_70) and two from Malawi (MW16, MW40) formed a clade which is significantly divergent from other CBSV isolates (we term this clade CBSV*) and the UCBSV isolates respectively (Fig. 1). We have tentatively named this group CBSV-Tanzania as it is more closely related to CBSV than UCBSV isolates and contains sequences predominantly from Tanzania. The clade includes the CBSV isolate Tan_70 from coastal Tanzania which was previously reported [5]. Isolates belonging to the CBSV-TZ clade were closely related, sharing P1 gene sequences very different from those in the CBSV* and UCBSV clades (Fig. 2). P1 sequences in the CBSV-TZ clade have low sequence identity with P1 gene sequences of isolates in the CBSV* (63.2 to 70.9%) and UCBSV (62.0 to 65.4%) clades.

Fig. 1.

ML tree of partial P1 gene sequences of Cassava brown streak viral isolates (Table 1). Sequences are from Tanzania (green), Mozambique (yellow), Kenya (red), Uganda (purple) and Malawi (blue). Bootstrap values higher than 70% are shown. The scale is in substitutions/site

Fig. 2.

Pairwise identity matrix generated from CBSV partial P1 gene sequences. Each colored key represents a percentage to the identity score between two sequences

Discussion

As CBSD continues to threaten subsistence cassava production in east, central and southern Africa, there is a need to understand dynamics of viral diversity as this has implications on evolution and emergence of new species or strains. This is especially critical in light of the rapid spread of the disease from the Great Lakes region of east and central-southern Africa [8, 9, 11–13, 20]. We present here an analysis of 64 partial P1 sequences of cassava brown streak viruses from cassava growing regions of Africa where CBSVs are known to occur. Considerable variance of gene size and sequence within P1 genes of the family Potyviridae has been previously reported [17, 14] indicating that P1 is an ideal region to reveal population differentiation and incipient speciation within cassava ipomoviruses. Further, whole genome analyses of CBSVs had previously identified unusual sequence diversity in P1 [5]. Our phylogenetic analysis revealed that the CBSVs sequences formed three distinct clades (Figure 1). In addition to the previously characterized species UCBSV and CBSV, the novel clade which includes the Tan_70 isolate [5] presents a major sub-group of CBSV, for which we propose the tentative name CBSV-Tanzania.

Another study on variation of CBSVs, based on short coat protein fragments (~230 nt) revealed a number of viruses that are intermediate between the two CBSV and UCBSV species subgrouping, and consequently presented a hypothetical possibility of a new novel species or sub-species associated with CBSVs [30]. Recent whole genome analyses of UCBSV isolates [9] suggested further speciation among isolates of UCBSV from Tanzania. Our results, concentrating on the analysis of the variable P1 gene and additional virus isolates from east and central-southern Africa, confirm the diversity observed with the in other studies and provides evidence from P1 gene analysis for subdivision of CBSV and the presence of the clade CBSV-TZ. Our results also show that the Malawi and Tanzania viruses are more diverse than those found in Kenya, Uganda, and Mozambique (Figure 1). That Tanzania has qualitatively higher diversity of CBSVs may not just be due to increased surveillance and sampling there; while UCBSV is distributed all over Malawi, CBSV* and sub-group CBSV-TZ are localized in northern Malawi, bordering Tanzania [30]. Movement of cultivars between the two countries could help to explain the shared diversity of CBSVs, which could be due to either purely geographical reasons or unique adaptations of circulating CBSV-TZ to locally popular cassava cultivars.

While the region around Lake Malawi was where CBSD was first observed [6] the higher prevalence and wide distribution of UCBSV compared to CBSV throughout Malawi, Tanzania and surrounding countries suggest that UCBSV was likely the virus implicated in the first finding of CBSD. Comparisons of full genome sequences of Malawian CBSVs with those of CBSVs obtained from CBSD-affected areas of neighboring countries (Tanzania and Mozambique) would likely clarify questions about the evolutionary history and biogeography of the viruses in the region. Regardless, it is clear that the CBSVs do not have geographically distinct distributions as was previously hypothesized [4].

Studies by Ndunguru et al. [9] showed that a previously described CBSV Tanzanian isolate TZ-Nal 07 had a recombination event in the 5′ end in the P1 gene. The P1 region is known to harbor obvious recombination in several potyviruses [31] and contributes to its overall variability. Although our final dataset did not statistically support recombination breakpoint (s) within P1, when diverse isolates from Kenya [32] were left out of the analysis, the isolate (TZ-Nal 07) was identified by two methods as a putative recombinant between a member of the CBSV-TZ clade (TZ:Kor6:08) and CBSVMo_83 (data not shown). This recombination event may be better supported from the full genome dataset [9] but the finding is consistent with the phylogenetic placement of TZ-Nal 07 as basal to the CBSV-TZ clade. However, we have no evidence for recombination being the origin for this well-supported subgroup and hence the diversification of P1 in the genomes of CBSV-TZ isolates still requires further investigation.

Conclusions

Our in-depth look at CBSVs from Malawi and Tanzania has revealed that the divergent Tan_70 isolate is in good company, and that the CBSVs have three separable groups of diverse P1 gene sequences. Further research will establish if the variable P1 region is an accurate bellwether for overall population divergence, and future phenotypic characterization will determine whether CBSV-TZ represents a novel strain or subspecies of CBSV.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all technical personnel at Mikocheni Agricultural Research Institute, Tanzania and Chitedze Agricultural Research Station, Malawi, for support in field sampling and collection of cassava stems. Financial contribution from Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation (Grants no. 51466 and 1052391) and the UK Department for International Development is also greatly appreciated.

Funding

We greatly acknowledge full financial support from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation (Grants no. 51466 and 1,052,391) and the UK Department for International Development, through sub grant to the Department of Agricultural Research Services (DARS), Chitedze Agricultural Research Station under the auspices of Mikocheni Agricultural Research Institute (MARI) through the “Disease Diagnostics for Sustainable Cassava Production in Africa project”. None of the funders had any influence on the design, collection or analysis or data interpretation.

Availability of data and materials

All sequences generated have been deposited into GenBank (KY289995-KY290025).

Authors’ contributions

WM and FT collected cassava samples, WM, SS, MK and SW reared cassava cuttings, WM, FT SS, MK and SW isolated and sequenced viral RNA, WM, SD and SW conducted phylogenetic analysis, WM, FT, PS, JN, SD, SM, IB, SS, MK and SW wrote and edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not Applicable

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not Applicable

Abbreviations

- CBSD

Cassava brown streak disease

- CBSV

Cassava brown streak virus

- CBSV-TZ

Cassava brown streak Tanzania

- cDNA

complementary Deoxyribonucleic Nucleic Acid

- CMD

Cassava mosaic disease

- MEGA

Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis

- ML

Maximum Likelihood

- RNA

Ribonucleic Acid

- RT-PCR

Reverse Transcriptase – Polymerase Chain Reaction

- SDT

Sequence Demarcation Tool

- UCBSV

Ugandan cassava brown streak virus

Contributor Information

Willard Mbewe, Email: mbewewillard@yahoo.co.uk.

Fred Tairo, Email: fredtairo@gmail.com.

Peter Sseruwagi, Email: psseruwagi@yahoo.co.uk.

Joseph Ndunguru, Email: jndunguru2003@yahoo.co.uk.

Siobain Duffy, Email: duffy@aesop.rutgers.edu.

Ssetumba Mukasa, Email: sbmukasa@gmail.com.

Ibrahim Benesi, Email: ibenesi63@gmail.com.

Samar Sheat, Email: s.sheat@hotmail.com.

Marianne Koerbler, Email: marianne.koerbler@jki.bund.de.

Stephan Winter, Email: stephan.winter@dsmz.de.

References

- 1.B. L. Patil, J. P. Legg, E. Kanju, and C. M. Fauquet, “Cassava brown streak disease: a threat to food security in Africa,” J Gen Virol, vol. 96, no. 5. Society for General Microbiology, pp. 956–968, 01-May-2015. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Legg JP, Jeremiah SC, Obiero HM, Maruthi MN, Ndyetabula I, Okao-Okuja G, Bouwmeester H, Bigirimana S, Tata-Hangy W, Gashaka G, Mkamilo G, Alicai T, Lava Kumar P. Comparing the regional epidemiology of the cassava mosaic and cassava brown streak virus pandemics in Africa. Virus Res. 2011;159(2):161–170. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2011.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Monger WA, Seal S, Isaac AM, Foster GD. Molecular characterization of the cassava brown streak virus coat protein. Plant Pathol. 2001;50(4):527–534. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3059.2001.00589.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mbanzibwa DR, Tian Y, Tugume AK, Mukasa SB, Tairo F, Kyamanywa S, Kullaya A, Valkonen JPT. Genetically distinct strains of cassava brown streak virus in the Lake Victoria basin and the Indian Ocean coastal area of East Africa. Arch Virol. 2009;154(2):353–359. doi: 10.1007/s00705-008-0301-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Winter S, Koerbler M, Stein B, Pietruszka A, Paape M, Butgereitt A. Analysis of cassava brown streak viruses reveals the presence of distinct virus species causing cassava brown streak disease in East Africa. J Gen Virol. 2010;91(5):1365–1372. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.014688-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lister RM. Mechanical transmission of cassava Brown streak virus. Nature. 1959;182:1588–1589. doi: 10.1038/1831588b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hillocks R, Jennings D. Cassava brown streak disease: a review of present knowledge and research needs. Int J Pest Manag. 2003;49(3):225–234. doi: 10.1080/0967087031000101061. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alicai T, Omongo CA, Maruthi MN, Hillocks R, Baguma Y, Kawuki R, Bua A, Otim-Nape GW, Colvin J. Re-emergence of cassava Brown streak disease in Uganda. Am Phytopathol Soc. 2007;91(1):24–29. doi: 10.1094/PD-91-0024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ndunguru J, Sseruwagi P, Tairo F, Stomeo F, Maina S, Djinkeng A, et al. Analyses of twelve new whole genome sequences of cassava brown streak viruses and ugandan cassava brown streak viruses from East Africa: diversity, supercomputing and evidence for further speciation. PLoS One. 2015;10(10) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.A. M. Q. King, M. J. Adams, E. B. Carsten, and E. J. Lefkowitz, Virus Taxonomy: Classification and Nomenclature of Viruses. Ninth Report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses., no. 1.2012.

- 11.Adams MJ, Antoniw JF, Beaudoin F. Overview and analysis of the polyprotein cleavage sites in the family Potyviridae. Mol Plant Pathol. 2005;6(4):471–487. doi: 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2005.00296.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Valli A, López-Moya JJ, García JA. Recombination and gene duplication in the evolutionary diversification of P1 proteins in the family Potyviridae. J Gen Virol. 2007;88(3):1016–1028. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.82402-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rajamäki ML, Kelloniemi J, Alminaite A, Kekarainen T, Rabenstein F, Valkonen JPT. A novel insertion site inside the potyvirus P1 cistron allows expression of heterologous proteins and suggests some P1 functions. Virology. 2005;342(1):88–101. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2005.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.García-Arenal F, Fraile A, Malpica JM. Variation and evolution of plant virus populations. Int Microbiol. 2003;6(4):225–232. doi: 10.1007/s10123-003-0142-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Glasa M, Malinowski T, Predajňa L, Pupola N, Dekena D, Michalczuk L, Candresse T. Sequence variability, recombination analysis, and specific detection of the W strain of plum pox virus. Phytopathology. 2011;101(8):980–985. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-12-10-0334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mbanzibwa DR, Tian Y, Mukasa SB, Valkonen JPT. Cassava brown streak virus (Potyviridae) encodes a putative Maf/HAM1 pyrophosphatase implicated in reduction of mutations and a P1 proteinase that suppresses RNA silencing but contains no HC-pro. J Virol. 2009;83(13):6934–6940. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00537-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alicai T, Ndunguru J, Sseruwagi P, Tairo F, Okao-Okuja G, Nanvubya R, Kiiza L, Kubatko L, Kehoe MA, Boykin LM. Cassava brown streak virus has a rapidly evolving genome: implications for virus speciation, variability, diagnosis and host resistance. Sci Rep. 2016;6:36164. doi: 10.1038/srep36164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Duffy S, Shackelton LA, Holmes EC. Rates of evolutionary change in viruses: patterns and determinants. Nat Rev Genet. 2008;9(4):267–276. doi: 10.1038/nrg2323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gibbs A, Ohshima K. Potyviruses and the digital revolution. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 2010;48:205–223. doi: 10.1146/annurev-phyto-073009-114404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ding S-W. RNA-based antiviral immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10(9):632–644. doi: 10.1038/nri2824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lodhi MA, Ye G-N, Weeden NF, Reisch BI. A simple and efficient method for DNA extraction from grapevine cultivars and Vitis species. Plant Mol Biol Report. 1994;12:6–13. doi: 10.1007/BF02668658. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mohammed IU, Abarshi MM, Muli B, Hillocks RJ, Maruthi MN. The symptom and genetic diversity of cassava brown streak viruses infecting cassava in east africa. Adv Virol. 2012;2012:795697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Kearse M, Moir R, Wilson A, Stones-Havas S, Cheung M, Sturrock S, Buxton S, Cooper A, Markowitz S, Duran C, Thierer T, Ashton B, Meintjes P, Drummond A. Geneious basic: an integrated and extendable desktop software platform for the organization and analysis of sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2012;28(12):1647–1649. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.B. M. Muhire, A. Varsani, and D. P. Martin. SDT: A virus classification tool based on pairwise sequence alignment and identity calculation. PLoS ONE.2014;9: 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Martin DP, Murrell B, Golden M, Khoosal A, Muhire B. RDP4: detection and analysis of recombination patterns in virus genomes. Virus Evol. 2015;1(1):1–5. doi: 10.1093/ve/vev003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Posada D. Evaluation of methods for detecting recombination from DNA sequences: empirical data. Mol Biol Evol. 2002;19(5):708–717. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a004129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Larkin MA, Blackshields G, Brown NP, Chenna R, Mcgettigan PA, McWilliam H, Valentin F, Wallace IM, Wilm A, Lopez R, Thompson JD, Gibson TJ, Higgins DG. Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics. 2007;23(21):2947–2948. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kumar S, Stecher G, Tamura K. MEGA7: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol Biol Evol. 2016;33(7):msw054. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nei M. Kumar S. Molecular Evolutionand Phylogenetics. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2000;154(2).

- 30.Mbewe W, Kumar PL, Changadeya W, Ntawuruhunga P, Legg J. Diversity, distribution and effects on cassava cultivars of cassava Brown streak viruses in Malawi. J Phytopathol. 2015;163(6):433–443. doi: 10.1111/jph.12339. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Larsen RC, Miklas PN, Druffel KL. Sequence data suggests a recombination event between a strain of bean common mosaic virus (BCMV) and bean common mosaic necrosis virus (BCMNV) Phytopathology. 2003;93:S48. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kathurima T, Nyende A, Kiarie S, Ateka E. Genetic diversity and distribution of cassava Brown streak virus and Ugandan cassava Brown streak virus in major cassava-growing regions in Kenya. Annu Res Rev Biol. 2016;10(5):1–9. doi: 10.9734/ARRB/2016/26879. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mbanzibwa DR, Tian YP, Tugume AK, Patil BL, Yadav JS, Bagewadi B, et al. Evolution of cassava brown streak disease-associated viruses. J Gen Virol. 2011;92(4):974–87. doi: 10.1099/vir.0. 026922–0. PMID: 21169213. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Monger, W.A., Alicai, T., Ndunguru. J., Kinya, Z.M., Potts, M., Reeder, R.H., et al. The complete genome sequence of the Tanzanian strain of Cassava brown streak virus and comparison with the Ugandan strain sequence. Arch Virol. 2010; 155:429–33. doi: 10.1007/s00705-009-0581-8 PMID: 20094895. [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All sequences generated have been deposited into GenBank (KY289995-KY290025).