Highlights

-

•

Ultrasonography is a useful tool for portal venous gas identification in critically ill patients.

-

•

Portal venous gas can be observed at the early phase of acute mesenteric ischemia.

-

•

Transient portal venous gas with rapid disappearance is indicative of the resolution of the ischemia.

Abbreviations: AMI, acute mesenteric ischemia; ICU, Intensive Care Unit; PVG, portal venous gas; CT, computed tomography; US, ultrasonography

Keywords: Portal venous gas, Acute mesenteric ischemia, Ultrasonography, Computed tomography

Abstract

Objectives

To report the utility of abdominal ultrasonography (US) to identify the presence of portal venous gas (PVG) during non-occlusive mesenteric ischemia (NOMI), and to follow the disappearance of portal venous gas after resolution of the NOMI.

Data sources

This was a clinical observation of a patient, with images of abdominal computed tomography (CT), and a video of portal venous gas identified by ultrasonography.

Data synthesis

We describe the case of an adult patient admitted to our ICU for NOMI developing 48 h after cardiac surgery. Medical intensive care associated with jejunal resection and vacuum-assisted closure led to rapid recovery. Three weeks later, the patient presented acute pulmonary edema, and developed a new episode of NOMI that was suspected by identification of PVG on US, and then confirmed on abdominal CT. The patient rapidly improved after orotracheal intubation and treatment of pulmonary edema. A second US performed 9 h later showed disappearance of PVG. The laparotomy performed 10 h after the first US did not find evidence of small bowel or colon ischemia. The postoperative period was uneventful.

Conclusions

US is a useful tool for the detection of PVG in critically ill patients, prompting suspicion of AMI. PVG can be observed at the early phase of AMI, even before irreversible transmural gut ischemia; transient PVG that disappears rapidly (within several hours) may suggest resolution of the NOMI.

1. Introduction

Acute mesenteric ischemia is a life-threatening complication among critically ill patients with shock. The diagnosis of acute mesenteric ischemia in the critically ill is frequently delayed because its presentation is not specific. Several cases of transient portal venous gas identified on abdominal CT have been reported with good evolution under medical treatment alone [1], [2], [3]. Abdominal ultrasonography is a bedside diagnostic tool allowing easy visualization of portal venous gas by the intensivist. According to the SCARE criteria, we report the first case of transient portal venous gas whose disappearance of gas was identified using US [4].

2. Case report

An adult patient with a personal history of smoking, atrial fibrillation, aortic insufficiency, and chronic bronchitis, was admitted to the ICU for shock 48 h after surgical aortic valve replacement for severe aortic valve disease. Acute mesenteric ischemia was rapidly suspected given the presence of acute abdomen, lactic acidosis, and shock. High-dose norepinephrine infusion, fluid loading with 0.9% saline, and wide-spectrum antibiotic therapy was initiated. Urgent abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan did not find evidence of acute mesenteric ischemia (AMI). However, since the shock was persistent, laparotomy was performed, and found necrosis of 40 cm of the jejunum that was resected, and a vaccum-assisted closure device was inserted. Since the mesenteric arteries and veins were permeable, a diagnosis of non-occlusive mesenteric ischemia associated with focal transmural jejunal necrosis was retained. In the first week, 4 interventions were performed by laparotomy, and a total of 70 cm of jejunum were resected. Bacterial samples from the peritoneum were negative, but mycological samples identified the presence of Candida, which was treated by fluconazole. The post-operative course was progressively favorable. However, 3 weeks later, after the patient had been extubated and weaned off catecholamines, he developed acute respiratory failure with hypoxia, tachypnea, and mottling, without hypotension. Arterial blood gases showed hypoxia and compensated metabolic acidosis with normal pH, lactate, aspartate aminotransferase, and plasma creatinine concentrations. Transthoracic echocardiography showed central mitral insufficiency and mitral Doppler found an E wave velocity of 200 cm/s with E/A > 2. Anterior pulmonary US showed numerous and mobile B lines, which, associated with the mitral Doppler, were in favor of a diagnosis of acute pulmonary edema of cardiac origin. Abdominal US performed on the right side of the trunk, using the “hepatic window”, found mobile echoes in the main trunk of the portal vein directing towards the liver, identified as dynamic portal venous gas (PVG), and multiple hyperechoic foci within the liver parenchyma, identified as static PVG (Video 1 in Supplementary file). We judged the patient to be presenting new onset AMI. The patient was sedated, orotracheal intubation was performed, limited fluid loading with cristalloids was initiated, norepinephrine was introduced, and wide-spectrum antibiotic therapy targeting digestive bacteria was administered. Urgent abdominal CT performed immediately after the US confirmed the presence of PVG, which was limited to rare bubbles in the liver parenchyma (Fig. 1) and in the mesenteric veins, and limited pneumatosis intestinalis on the small bowel, while the mesenteric arteries were permeable. The surgeon on call was contacted with a view to performing laparotomy that night, but the operating room was not immediately available. In the first few hours after orotracheal intubation, the patient rapidly stabilized under 0.3 γ.kg.min−1 norepinephrine infusion, with disappearance of mottling, persistent diuresis, and with normal pH and lactate concentrations. A second US performed 9 h after the previous one showed the complete disappearance of both dynamic and static PVG (Video 2 in Supplementary file). The laparotomy performed one hour later did not find any macroscopic evidence of ischemia, either in the small bowel or the colon, and no resection was performed. In the following days, the patient recovered rapidly, without recurrence of acute mesenteric ischemia. One year later, the patient had returned home and resumed normal physical activity.

Fig. 1.

Abdominal computed tomography performed immediately after the first abdominal ultrasonography, and showing isolated small bubbles of portal venous gas (arrow) in the liver.

3. Discussion

The main messages of this case report are the following: firstly, there is a possible discordance between ultrasonography and abdominal CT as regards identification of PVG, with ultrasonography being more sensitive for the visualization of small amounts of gas. Secondly, PVG may be observed at the early phase of AMI, even before the constitution of transmural necrosis. Finally, PVG can be transient, and the rapid disappearance of PVG may be a factor that is associated with favorable outcome.

This case report illustrates the possible discordance between US and CT for the visualization of PVG. Indeed, whereas US identified mobile echoes in the trunk of portal vein and evidence of gas accumulation in the liver parenchyma, abdominal CT found only localized bubbles in the liver parenchyma and mesenteric veins, but not in the portal vein. This observation adds further evidence to the hypothesis that US is more sensitive than CT for identifying small amounts of gas in the liver [5], [6], [7], [8], [9]. This point has been developed by Hollerweger et al. who showed that, based on the physical properties and technology used for CT and US, CT cannot identify very small amounts of gas, whereas US can [8]. In our experience, patients presenting with PVG on CT also have PVG detectable on US, whereas PVG seen on US is not systematically associated with PVG on CT.

In our case, the PVG was seen on US in a patient presenting with peripheral signs of hypoperfusion, but without hypotension, and interestingly, with normal plasma concentrations of creatinine, ASAT and lactates. This suggests that US visualization of PVG can be an early event in the pathogenesis of AMI, and could precede the constitution of transmural infarction, which is generally associated with shock state, acute renal failure, metabolic lactic acidosis, elevated ASAT, and massive PVG on abdominal CT [10].

The visualization of PVG was transient. Indeed, a second abdominal US performed 9 h after the first showed the complete disappearance of both dynamic and static PVG. Several cases have been reported of patients presenting with transient PVG identified on successive abdominal CT. First, Coulier et al. found transient PVG in a patient with hypovolemic shock and gastrointestinal occlusion, with disappearance of PVG after correction of the shock and stomach decompression using a nasogastric tube [1]. Second, Suzuki et al. identified transient PVG in a dialysis patient presenting with hypotension, with the PVG disappearing within 18 h with conservative treatment [2]. Third, Morisaki reported a patient with ischemic enteritis and transient PVG, which disappeared with conservative treatment [3]. In the present case, PVG was identified in an unstable patient presenting with hypoxia and mottling. In contrast, the second US was performed once the patient was stabilized, with no signs of either acute pulmonary edema or peripheral hypoperfusion. It is likely that the patient initially presented non-occlusive mesenteric ischemia on-occlusive mesenteric ischemia (NOMI) that was reversible after orotracheal intubation and treatment of the acute pulmonary edema [11]. After the resolution of NOMI, the gut source of gas could have dried up, and the intrahepatic accumulation of gas could have resorbed progressively. This case report supports the evidence that, if the source of mesenteric gas is corrected, intra-hepatic accumulation of gas can be resorbed within few hours.

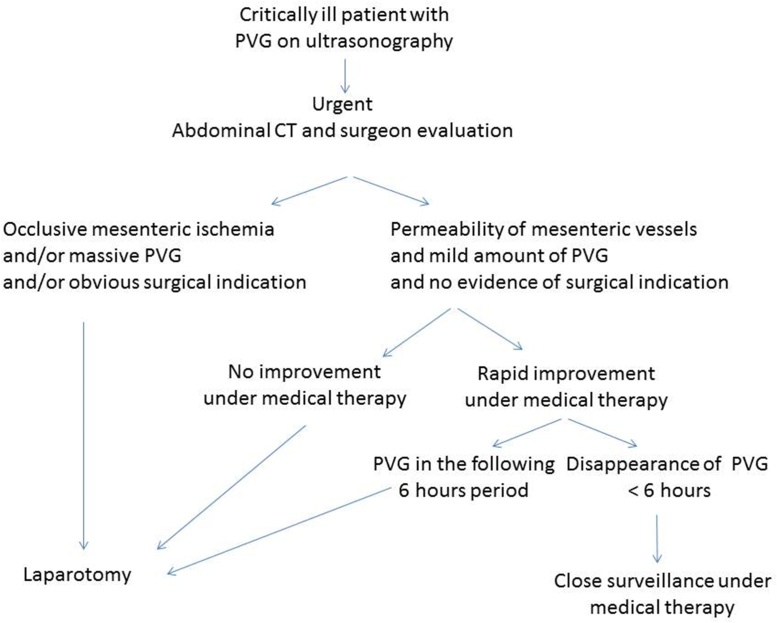

There was no evidence of transmural small bowel or colon ischemia at laparotomy examination. This laparotomy was performed one hour after the normalization of US showing disappearance of both dynamic and static PVG. This observation suggests that the transient visualization of PVG is not necessarily associated with poor prognosis, and that may be useful to follow PVG development with US. Indeed, reported cases of transient PVG were associated with good recovery with conservative treatment alone [1], [2], [3]. We suggest that among critically ill patients presenting with PVG on ultrasonography, when abdominal CT shows permeability of the mesenteric vessels, mild amounts of PVG, and absence of surgical indication, and when the clinical status rapidly improves under medical therapy, then monitoring of PVG after 6 h could be performed, thus avoiding laparotomy in patients in whom PVG disappears (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Proposed algorithm for a diagnostic strategy among critically ill patients presenting with portal venous gas on ultrasonography. PVG, portal venous gas; CT, computed tomography.

There are several limitations to the use of US in the context of AMI in the critically ill. Firstly, US is not the best imaging technique for the confirmation of acute mesenteric ischemia: abdominal CT with contrast enhanced injection should always be performed where possible when acute mesenteric ischemia is suspected (Fig. 2). Indeed, contrary to US, abdominal CT enables accurate analysis of the mesenteric veins and arteries, and can identify obvious surgical indications such as pneumoperitoneum or peritonitis. Secondly, performing US can be difficult in critically ill patients. Indeed, wound dressings, edema, difficulty moving the patient to obtain an appropriate position for US, and inexperience of the operator are limiting factors. However, using the “hepatic window” on the right side of the trunk, as reported in this case, allows good visualization of the liver and portal vein, and PVG can easily be identified.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Fiona Ecarnot (EA3920, University Hospital Besancon, France) for translation and editorial assistance.

Prof. Capellier has consulted for Gambro, received grant support from General Electric, payment for development of educational presentations from LFB, and travel reimbursements from the “Don Du Souffle Franche Comte” foundation. The remaining authors do not have any potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijscr.2017.05.041.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are Supplementary data to this article:

Video of the first abdominal ultrasonography showing multiple hyperechoic foci within the liver parenchyma corresponding to intrahepatic accumulation of portal venous gas.

Video of the second abdominal ultrasonography, performed nine hours later, showing complete disappearance of portal venous gas.

References

- 1.Coulier B., Van den Broeck S., Coppens J.-P. Transient and rapidly resolving intrahepatic portal gas: CT findings. JBR-BTR Organe Société R Belge Radiol SRBR Orgaan Van K Belg Ver Voor Radiol KBVR. 2008;91(5):214–216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Suzuki K., Umaoka A., Katayama N., Imai H. Transient extensive hepatic portal venous gas following hypotension in a dialysis patient. BMJ Case Rep. 2013;2013 doi: 10.1136/bcr-2013-009162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morisaki T., Ohba K., Yoshida A., Mizuta Y., Nakao K. A case of hepatic portal venous gas caused by transient type ischemic enteritis. Nihon Shokakibyo Gakkai Zasshi Jpn. J. Gastro-Enterol. 2010;107(3):407–415. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Agha R.A., Fowler A.J., Saeta A., Barai I., Rajmohan S., Orgill D.P. The SCARE Statement: Consensus-based surgical case report guidelines. Int. J. Surg. Lond. Engl. 2016;34:180–186. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2016.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maher M.M., Tonra B.M., Malone D.E., Gibney R.G. Portal venous gas: detection by gray-scale and Doppler sonography in the absence of correlative findings on computed tomography. Abdom. Imaging. 2001;26(4):390–394. doi: 10.1007/s002610000192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chevallier P., Peten E., Souci J., Chau Y., Padovani B., Bruneton J.N. Detection of portal venous gas on sonography, but not on CT. Eur. Radiol. 2002;12(5):1175–1178. doi: 10.1007/s00330-001-1144-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oktar S.O., Karaosmanoğlu D., Yücel C., Erbaş G., Ilkme A., Canpolat I. Portomesenteric venous gas: imaging findings with an emphasis on sonography. J. Ultrasound Med. Off. J. Am. Inst. Ultrasound Med. 2006;25(8):1051–1058. doi: 10.7863/jum.2006.25.8.1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hollerweger A., Rettenbacher T. Detection of portal venous gas on sonography, but not on CT. Eur. Radiol. 2003;13(Suppl 4):L251–L253. doi: 10.1007/s00330-003-1899-3. (author reply L254) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Piton G., Capellier G., Delabrousse E. Echography of the portal vein in a patient with shock. Crit. Care Med. 2016;44(6):e443–445. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guillaume A., Pili-Floury S., Chocron S., Delabrousse E., De Parseval B., Koch S. Acute mesenteric ischemia among post-Cardiac surgery patients presenting with multiple organ failure. Shock Aug. Ga. 2017;47(3):296–302. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0000000000000720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Björck M., Wanhainen A. Nonocclusive mesenteric hypoperfusion syndromes: recognition and treatment. Semin. Vasc. Surg. 2010;23(1):54–64. doi: 10.1053/j.semvascsurg.2009.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Video of the first abdominal ultrasonography showing multiple hyperechoic foci within the liver parenchyma corresponding to intrahepatic accumulation of portal venous gas.

Video of the second abdominal ultrasonography, performed nine hours later, showing complete disappearance of portal venous gas.