Abstract

A 48-year-old male was diagnosed with both drug resistant epilepsy and psychogenic nonepileptic seizures. Both diagnoses were confirmed by video-EEG monitoring. His epileptic seizures were a consequence of right mesial temporal sclerosis. He was diagnosed by a psychiatrist to have depression and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Following a right anterior temporal resection he became seizure free (both epileptic and nonepileptic) with a remarkable improvement in his psychiatric comorbidities leading to significant reduction in his psychotropic medications.

No reports have been identified in the literature of patients with epilepsy and PNES with coexisting PTSD having epilepsy surgery.

1. Introduction

Drug resistant epilepsy carries increased risk of injury and death. Patients with drug resistant epilepsy should be investigated for surgical options seeking to achieve seizure freedom.

Differentiating psychogenic nonepileptic seizures (PNES) from epileptic seizures can be a challenge. Both conditions can coexist with multiple reports estimating the presence of epilepsy in patients with PNES to be less than 10% [1], [3], [5].

Although some authors consider the presence of PNES a relative contraindication for surgical consideration [2], few reports have been published reporting improvement of both epileptic and psychogenic seizures following surgical resection [3].

We report a patient with coexisting epilepsy, PNES, depression and PTSD who had a remarkable improvement in all of his comorbidities following successful epilepsy surgery.

1.1. Case report

This 48-year-old male was admitted to the Epilepsy Monitoring Unit (EMU) at the QEII Health Science Centre in Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada.

He had a cluster of seizures and left-sided weakness at age 1 year secondary to presumed encephalitis with no further information known about that diagnosis. The left-sided weakness resolved by age 4 years. He had no further neurological issues until age 42 years.

At age 42 years he started to have “spells” that were more in keeping with non epileptic seizures, described as asymmetric shaking starting in one leg then slowly progressing over 2–3 min to involve all four limbs lasting for 5–10 min. These spells were occurring almost every day. A detailed description of these events will be given later as some of these spells were captured on video during the patient's admission to the epilepsy monitoring unit (EMU).

Approximately one year later, he began to experience new attacks: (a) diurnal seizures consisting of a rising epigastric sensation followed by loss of consciousness and convulsive movements and, (b) nocturnal convulsive seizures, accompanied by tongue biting and/or urine incontinence.

He was diagnosed by a psychiatrist with depression (at age 43 years) and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) related to military experience at the age of 44 years.

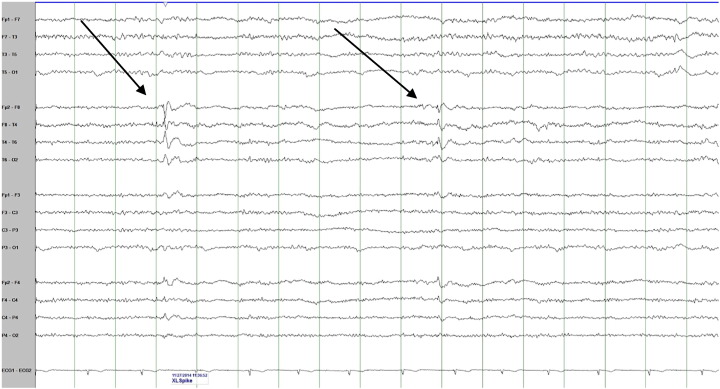

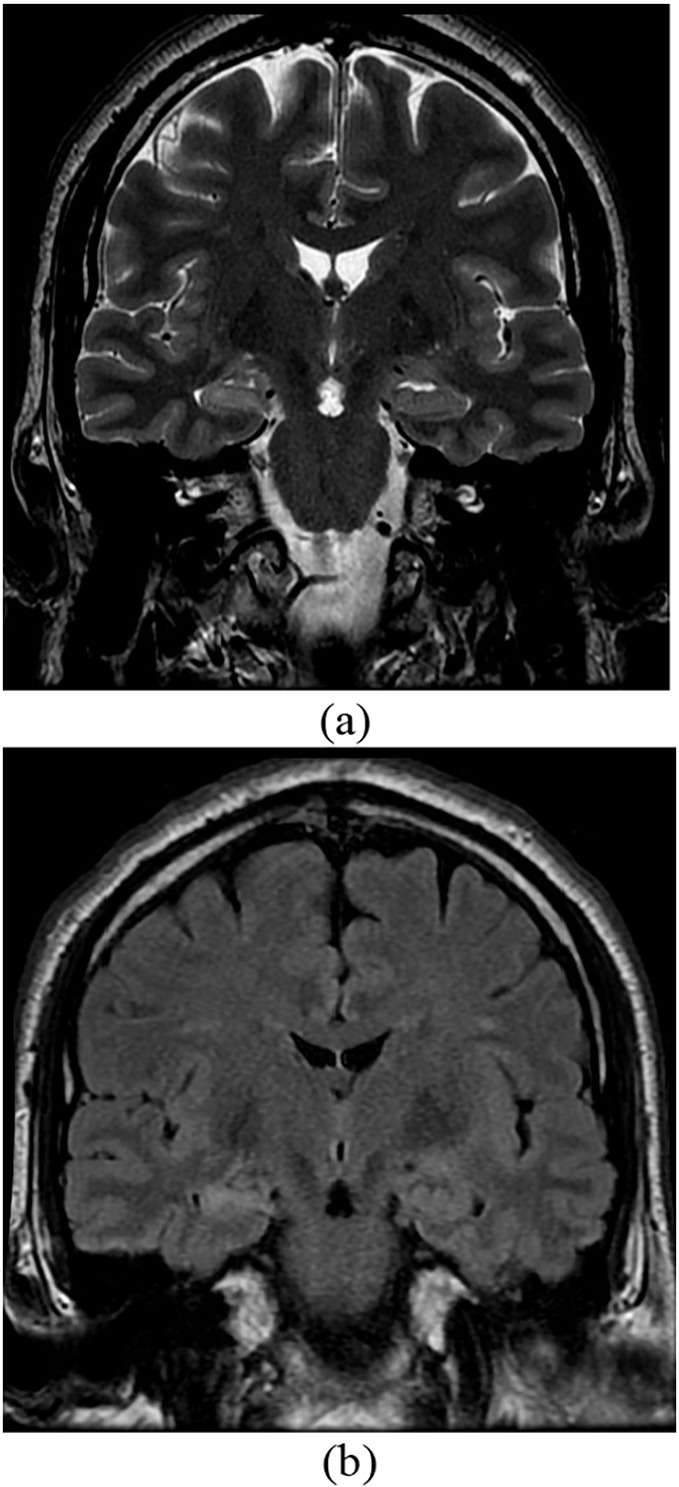

He was admitted to the EMU for video-EEG initially for diagnostic evaluation. In the same year he started to have the nocturnal events. He had three of these events recorded with EEG and accompanying video. The events began with focal rhythmic movements (in one finger or in the foot, either right or left) that slowly evolved to other body parts in a random fashion. Later, side-to-side shaking with “head nodding” type movement was seen. He could follow commands during these spells. They lasted between 2 to 8 minutes. There was a clear alpha rhythm at the beginning of the attacks before it became masked by muscle artifact with no evidence of any epileptiform discharges on the EEG. These were diagnosed as unequivocal psychogenic nonepileptic events. However, his interictal EEG recording showed abundant right anterior temporal spikes (Fig. 1). His MRI brain showed evidence of right hippocampal sclerosis (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

An interictal EEG sample showing 2 examples of interictal right anterior temporal spikes (see arrows).

Fig. 2.

Coronal MRI brain samples of the patient with T2 (a) and T2 Flair (b) demonstrated right mesial temporal sclerosis.

Despite treatment with various combinations of phenytoin, levetiracetam, carbamazepine, clobazam, lamotrigine, valproic acid and lacosamide, he continued to have focal epileptic seizures with impaired awareness evolving to bilateral tonic–clonic seizures at a frequency of 1 every 1–2 months and nonepileptic events at a frequency of 1–5 per month. He continued to have nightmares related to PTSD on a nightly basis. His wife believed that she could confidently differentiate epileptic from nonepileptic seizures. This became clearer to her when she was shown the EMU videos of both types of events.

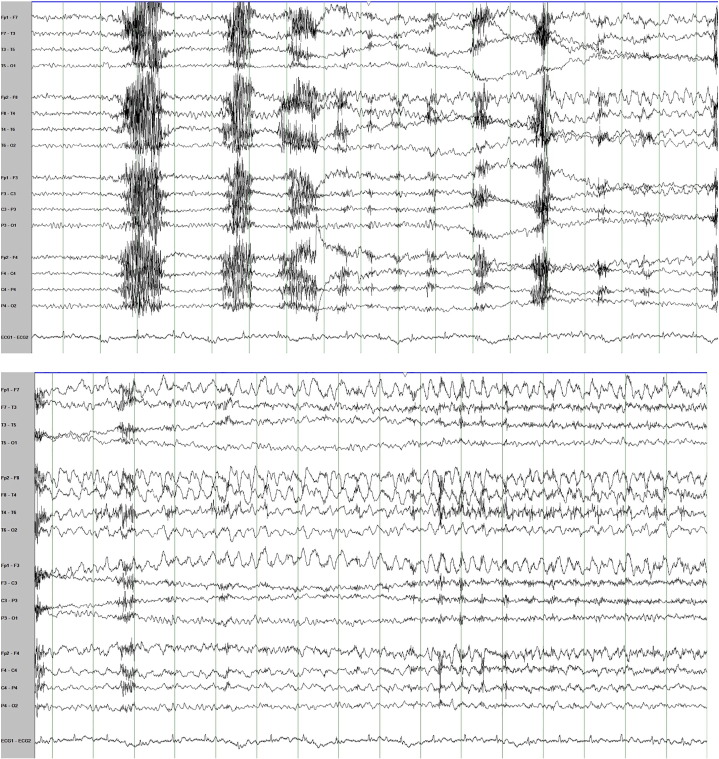

He was admitted again to the EMU for 4 weeks of presurgical evaluation. Nine right temporal seizures were recorded, 2 of which evolved to bilateral tonic–clonic seizures. These were clearly different than the events recorded during the previous EMU admission. They were stereotyped and characterized by sudden onset of behavioral arrest followed by chewing movements lasting for 1 minute and then on two occasions evolving to bilateral tonic–clonic seizures. On the EEG all nine seizures had clear right temporal lobe ictal onset (Fig. 3). None of the nonepileptic spells were recorded. The interictal recording showed frequent exclusively right temporal interictal epileptiform discharges.

Fig. 3.

Two consecutive epochs of EEG showing the onset and the evolution of the right temporal ictal rhythm at the onset of one of the patient's recorded epileptic seizures.

The decision was made to proceed with a right temporal resection. Pathological analysis of the resected tissue revealed dual pathology including hippocampal sclerosis and focal cortical dysplasia (FCD) type 3A.

At 4 weeks post surgery, the patient and his wife reported no seizures of any kind. He reported that his depression and PTSD symptoms had resolved.

One year after the surgery, he continued to be completely free of all seizures (epileptic and nonepileptic) taking only lamotrigine as an anti-seizure medication. He reported a transient recurrence of depression and the PTSD symptoms following discontinuation of his antidepressant medications, without appropriate down titration, but recovered after these medications were adjusted by his psychiatrist.

2. Discussion

This case demonstrates a remarkable improvement in the patient's epileptic and nonepileptic seizures as well as his psychiatric comorbiditeis (depression and PTSD) following epilepsy surgery.

Focal cortical dysplasia and hippocampal sclerosis are common risk factors for focal epilepsy. In one review of FCD, the age at epilepsy onset ranged from < 1 to 60 years (mean: 5.8 years, median: 3 years) [8]. In the same review, patients with dual pathology (FCD located in the temporal lobe or temporo-occipitally and an additional hippocampal sclerosis) like our patient seemed to have an earlier age of epilepsy onset (ranged in one study from < 1 to 29 years) [8]. The first known epileptic seizure in the reported patient occurred at the age of 43. There is no clear explanation for this delay in seizure onset but it has been reported and sometimes referred to as “occult FCD” that would have late onset seizures.

Identifying epileptic seizures in patients diagnosed with PNES confirmed by video-EEG recording (as in this case) can be challenging. When such patients and the witnesses report different attacks with features resembling known epileptic seizures, this should warrant reinvestigation for the possibility of coexisting PNES.

In patients who have mixed PNES and epilepsy, there are conflicting reports about the outcome following surgery. Some authors consider the presence of PNES as a relative contraindication for epilepsy surgery [2]. In a report by Reuber et al. of 13 patients with PNES and epilepsy who had epilepsy surgery (in 10 of them, the seizures were originating from the temporal lobe but none of them had dual pathology), 7 patients became free from both epileptic and nonepileptic seizures (similar to our patient), 2 patients had an improvement of their epileptic seizures and became free of PNES, and only 2 patients had improvement of the epileptic seizures with no change in PNES. There were 2 patients who had no change in either the epileptic and nonepileptic seizures [3].

There have been many reports on the association between epilepsy and various psychiatric conditions. The prevalence of major depressive disorders in patients with epilepsy varied in different reports between 8% and 48% with a mean of 29%. Risk factors for developing depression in patients with epilepsy included poor medication compliance, worse seizure frequency, unemployment and a worse overall quality of life [7]. There is evidence that depression can exacerbate seizures, and treating depression may decrease seizure frequency [7].

Multiple reports indicated that the prevalence of depression in patients known to have PNES (21–60%) is significantly higher than the prevalence rates not only in the general population, but also in patients with epilepsy whose seizures are controlled, and in patients with treatment-resistant epilepsy [7].

In patients diagnosed with PTSD, epidemiological studies have documented elevated risk for a broad spectrum of disorders, including depression [6]. In a recent literature review that assessed depression comorbidity in combat-related PTSD (similar to our patient), there was some level of bidirectional causality, but the influence of PTSD on the development of comorbid depression appeared more consistent and stronger than the reverse risk [6].

Only few reports suggested an association of PTSD and epilepsy [4]. No reports have been identified in the literature of patients with coexisiting PTSD having epilepsy surgery and reporting remarkable improvement following the surgery.

In conclusion, nonepileptic seizures associated with PTSD should not exclude patients from surgical consideration for drug resistant epilepsy.

Acknowledgements

I would like to acknowledge Dr. R. Mark Sadler and Ms. Susan Rahey for editorial assistance in preparation of this paper.

References

- 1.Martin R., Burneo J.G., Prasad A., Powell T., Faught E., Knowlton R. Frequency of epilepsy in patients with psychogenic seizures monitored by video-EEG. Neurology. 2003;61:1791–1792. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000098890.13946.f5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Whitehead Kimberley, O'Sullivan Suzanne, Walker Matthew. Impact of psychogenic nonepileptic seizures on epilepsy presurgical investigation and surgical outcomes. Epilepsy Behav. 2015;46:246–248. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2015.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reuber M., Kurthen M., Fernández G., Schramm J., Elger C.E. Epilepsy surgery in patients with additional psychogenic seizures. Arch Neurol. 2002;59:82–86. doi: 10.1001/archneur.59.1.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kessler R.C., Lane M.C., Shahly V., Stang P.E. Accounting for comorbidity in assessing the burden of epilepsy among US adults: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) Mol Psychiatry. 2012;17(7):748–758. doi: 10.1038/mp.2011.56. [PubMed PMID: 21577213; PMCID: 3165095] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benbadis Selim R., Agrawal Vikas, Tatum William O., IV How many patients with psychogenic nonepileptic seizures also have epilepsy? Neurology. 2001;57:915–917. doi: 10.1212/wnl.57.5.915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stander Valerie A., Thomsen Cynthia J., Highfill-McRoy Robyn M. Etiology of depression comorbidity in combat-related PTSD: a review of the literature. Clin Psychol Rev. 2014;34:87–98. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2013.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kanner Andres M., Schachter Steven C., Barry John J., Hersdorffer Dale C., Mula Marco, Trimble Michael. Depression and epilepsy, pain and psychogenic non-epileptic seizures: clinical and therapeutic perspectives. Epilepsy Behav. 2012;24:169–181. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2012.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fauser Susanne, Huppertz Hans-Juergen, Bast Thomas, Strobl Karl, Pantazis Georgios, Altenmueller Dirk-Matthias. Clinical characteristics in focal cortical dysplasia: a retrospective evaluation in a series of 120 patients. Brain. 2006;129:1907–1916. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]