Highlights

-

•

Herniotomy and bilateral orchidopexy is recommended for TTE-PMDS.

-

•

No reports suggest malignancy from the mullerian structures.

-

•

Division of mullerian structures is done only if it interferes with orchidopexy.

-

•

Malignancy may arise in the testis though histologically normal.

Key words: Persistent mullerian duct syndrome, Transverse testicular ectopia, Testis, Cryptorchidism, Orchidopexy, Case report

Abstract

Introduction

Persistent Mullerian duct syndrome (PMDS) is a rare type of male pseudohermaphroditism. Transverse testicular ectopia (TTE) is characterized by one testis moving to the opposite side and both testes traversing the same inguinal canal.

Case presentation

An 11-month-old boy presented with bilateral cryptorchidism. The left testis was not palpable; the right testis was canalicular with a right inguinal hernia. Ultrasound showed both testes located in the right inguinal canal. Right inguinal exploration revealed two testes with intact spermatic cords. A primitive uterus with fallopian tubes was also identified on opening the processus vaginalis. After herniotomy, bilateral orchidopexy was carried out (left orchidopexy through a trans-septal approach). Karyotyping confirmed a male gender (46XY). One year after the operation, ultrasound showed both testes to be in good condition.

Discussion

PMDS is caused by defects in the gene that encodes Antimullerian hormone(AMH). Treatment aims to correct cryptorchidism and ensure appropriate scrotal placement of the testes. Malignant transformation is as likely as the presence of abdominal testes in an otherwise normal man. Failing early surgical correction, gonadectomy must be offered to prevent malignancy. Division of the persistent mullerian duct structures is indicated only in patients where persistence interferes with orchidopexy.

Conclusion

TTE should be suspected in patients presenting with inguinal hernia on one side and cryptorchidism on the other side. Herniotomy and bilateral orchidopexy is optimal. Removal of mullerian structures may injure the artery to vas deferens and is hence not recommended. Follow-up for fertility assessment in the latter years should be counselled.

1. Introduction

Persistent Mullerian duct syndrome (PMDS) occurs in a phenotypic and genotypic male who has a concurrent uterus, fallopian tubes, and an upper vagina as the mullerian ducts fail to regress. In transverse testicular ectopia (TTE), one of the testes moves to the opposite side and both testes pass the same inguinal canal. The concurrence of TTE and PMDS is extremely rare.

We report a patient with PMDS and TTE who presented with a right-sided inguinal hernia and left undescended testis. This child was managed in our tertiary care institution. This report highlights the pathogenesis and management of PMD and TTE, the possible complications of dividing these structures and the necessity for fertility follow-up and gonadectomy in certain situations.

2. Patient information

An 11-month-old boy was brought by his mother to our hospital for evaluation of bilateral cryptorchidism.

3. Clinical findings

The left testis was impalpable, the right testis was canalicular and a right inguinal hernia was present.

4. Timeline

Cryptorchidism was detected by the caregivers only at 11 months and the patient was brought in.

5. Diagnostic assessment

Ultrasound revealed a small left and a larger right testis, both located in the right inguinal canal. Karyotyping was 46XY.

6. Therapeutic intervention

An inguinal exploration was planned to correct the cryptorchidism. Pre-operative assessment and anesthetic clearance was obtained. The surgery was performed under general anesthesia with caudal block by a senior pediatric surgeon. Right inguinal exploration revealed bilateral testes with intact spermatic cords and a sac in the right inguinal region suggesting transverse testicular ectopia(Fig. 1). When the processus vaginalis was opened, a primitive uterus together with fallopian tubes was identified confirming the presence of persistent mullerian duct syndrome (Fig. 2, Fig. 3). After performing herniotomy, bilateral orchidopexy was carried out (left orchidopexy through a trans-septal approach). The mullerian structures were not divided to prevent injury to vessels supplying the testes and vas deferens. The patient was discharged the following day. Sutures were removed on the 10th postoperative day and no apparent complications were detected.

Fig. 1.

Both testes in right inguinal hernia.

Fig. 2.

Tubes and Uterus (Primitive) clearly seen.

Fig. 3.

TTE with PMDS.

7. Follow-up and outcomes

Postoperative follow-up was uneventful. One year after the operation, ultrasound showed both testes to be in good condition.

8. Discussion

An ectopic testis is one which is found in a location not along the standard path of testicular descent. This differentiates this anomaly from an undescended testis. Crossed or transverse testicular ectopia was first described by Von Lenhossek in 1886 [1]. TTE is characterized by both testes descending through a single inguinal canal and being on the same side with contralateral cryptorchidism.

The exact number of documented cases of TTE till date has not been reported. Fourcroy et al. summarized that about 100 cases of TTE had been reported till 1982 [2]. Our PubMed search identified 152 cases published after 1982 bringing the number of reported cases to about 260 till date.

TTE associated with PMDS is extremely rare and Ferri et al. state that 10 cases had been reported till 1999 [3]. Review of the PubMed database using ‘persistent mullerian duct syndrome with transverse testicular ectopia’ identified 47 more cases since 1999. Thus, to our knowledge there are only 57 reported cases of TTE with PMDS till date.

Various anatomic factors (defective implantation, rupture or tearing of the gubernaculum, obstruction of the internal inguinal ring, adhesions between the testis and adjacent structures, late closure of the umbilical ring, etc.) are suggested as causative factors in the failure of testicular descent.

TTE has been classified as three types: Type I accompanied by hernia (40–50%),Type 2 by persistent or rudimentary mullerian duct structures (30%) and Type 3 associated with disorders such as hypospadias, pseudohermaphroditism and scrotal abnormalities.

TTE patients sometimes have associated PMDS. Mullerian structures include fallopian tubes, uterus and the upper part of the vaginal canal. PMDS is characterized by the persistence of these structures in their primitive form in male children.

PMDS is caused by defects in the gene that encodes the synthesis or action of Mullerian inhibiting Factor or Antimullerian hormone [4], [5], [6], [7], [8]. AMH is secreted by the sertoli cells of the developing testes by 7 weeks of gestation. The other cause of persistence of Mullerian ducts, testicular dysgenesis, usually affects both Sertoli and Leydig cells. Persistence of Mullerian derivatives is then associated with external genital ambiguity.

Soon after testicular differentiation, AMH gene expression is induced by SOX9 in sertoli cells which results in an ipsilateral regression of the mullerian ducts by 8 weeks of gestation, before the emergence of testosterone secretion or the stimulation of the wolffian ducts [9].

The gene encoding AMH I is located in the short arm of chromosome 19(19p13.3). AMH signaling is mediated via a heterodimeric receptor consisting of type 1 and type 2 serine/threonine kinase receptor, the type 2 part of the receptor mediates ligand specificity and the type 1 receptor activates a downstream signaling cascade. ALK 2, ALK 3 and ALK 6 have all been linked to type 1 signaling and decreased expression or deletion of the former two disrupts mullerian duct regression [10]. The type 2 receptor is called as AMHR2 and is located on chromosome 12(12q13). AMH mutations are often autosomal recessive. Affected patients usually have an AMH gene mutation in 45%, and in the AMRH2 receptor gene in another 39%. In the remaining 15%, no mutation was detected, implicating genes coding for other factors in the AMH transduction cascade [11]. AMH and AMH2 receptor mutations are transmitted through an autosomal recessive pattern and are symptomatic only in males.

Female sexual development is not affected as AMH is not expressed during sexual differentiation in female fetuses. Lack of AMH promotes mullerian proliferation in females. In males, an absent AMH or its receptor prevents normal Müllerian duct regression and hence the child has both the urogenital ridges containing the Wolffian and the Mullerian ducts. So in addition to normal wolffian duct differentiation structures like the epididymis, vas deferens and seminal vesicles, there is a hypoplastic female genital tract. Neonates present with male external genitalia with normal development of the penis and scrotum, but with cryptorchidism.

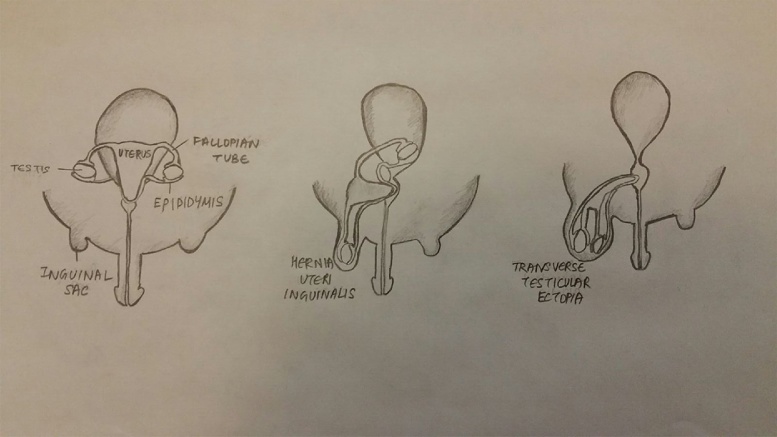

There are 3 clinical presentations of PMDS: (Fig. 4)

-

a

Testes in normal position of ovaries and inguinal sac empty (60–70%)

-

b

One testis in an inguinal hernia with attached tube and uterus (Hernia uteri inguinalis) (20–30%)

-

c

Both testes herniated into one processus vaginalis (Transverse testicular ectopia) (10%)

Fig. 4.

3 clinical presentations of PMDS.

In the first presentation, patients have bilateral impalpable intra-abdominal testes with retained Müllerian ducts that are identified on investigation often by laparoscopy [12]. The second presentation is characterized by hernia uteri inguinalis, in which a boy with unilateral cryptorchidism and an ipsilateral inguinal hernia is found to have a Fallopian tube with the testis inside the hernial sac. In the third type, the boy presents with cryptorchidism with an inguinal hernia that contains both the testes, Wolffian ducts and Müllerian ducts, which is known as transverse testicular ectopia. The cause of cryptorchidism and transverse testicular ectopia in PMDS is thought to be due to an abnormally long gubernacular cord, which is similar to a long round ligament in the uterus [13]. This excessive mobility of the intra-abdominal testes caused by a long gubernacular cord leads to a high incidence of gonadal torsion in patients with PMDS, so that there is a notably increased risk of testicular atrophy [14].

Some researchers have suggested that the putative mechanism for cryptorchidism in PMDS is a simple passive inhibition of testicular descent by the retained Müllerian ducts [15]. The mobility of the testes and frequency of torsion is strong evidence against the theory of retained Müllerian ducts passively blocking testicular descent.

PMDS is mostly discovered during surgery for inguinal hernia or for cryptorchidism. In all patients with inguinal hernia and cryptorchidism, an ultrasound evaluation must be considered to identify possible TTE and PMDS. TTE and PMDS patients have normal karyotype.

Treatment of PMDS is exclusively surgical and aims to correct cryptorchidism. The testes are usually histologically normal, though the germinal cells may be affected due to long-standing cryptorchidism. The overall incidence of malignant transformation in these testes is 18%, similar to the rate in abdominal testes in otherwise normal men. There have been reports of embryonal carcinoma, seminoma, yolk sac tumor and teratoma in patients with PMDS [16]. Early surgical intervention is necessary for testicular preservation, failing which gonadectomy must be offered to prevent malignancy [17]. Adequate surgery involves bilateral orchidopexy.

The division of the persistent mullerian duct structures is controversial as it may damage the artery to the vas deferens and is not advocated unless persistence interferes with orchidopexy. The testis can also be crossed across the root of the penis in the inguinal region and descended through the ipsilateral inguinal canal instead of going for a trans-septal approach of placing the contralateral testis [18]. Retroperitoneal transposition of the gonad can be done when the cord length does not permit trans-septal orchidopexy [19]. Early surgery promotes gonadal function and prevents subfertility.

TTE is a rare condition and should be suspected in patients presenting with inguinal hernia on one side and cryptorchidism on the other side. Optimal surgical approach should include herniotomy and bilateral orchidopexy. There are no reports of malignancy arising from Mullerian remnants and due to the risk of injuring the blood supply of testes and vas deferens, the removal of these structures is no longer recommended. A long-term follow-up is needed for the assessment of fertility in these patients.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to reveal.

Source of funding

This report did not receive any funding.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Author contributions

Aashish Rajesh – Drafting the manuscript, revision, approval of final version.

Mohammed Farooq – Performing surgery, revision, approval of final version.

Registration of research studies

Not applicable.

Guarantor

Aashish Rajesh.

Patient perspective

The patient’s mother felt relieved with the surgical result.

Informed consent

This publication is subsequent to a documented consent from the patient’s mother after adequate explanation and assurance of anonymity.

Additional information

This case report has been reported in line with the SCARE criteria [20].

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijscr.2017.06.016.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Von Lenhossek M.N. Ectopia testis transversa. Anat. Anz. 1886;1:376–381. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fourcroy J.L., Belman A.B. Transverse testicular ectopia with persistent Müllerian duct. Urology. 1982;19(5):536–538. doi: 10.1016/0090-4295(82)90614-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferri M., Ansari S., deMaria J. Persistent Mullerian duct syndrome associated with transverse testicular ectopia. Can. J. Urol. 1999;6:865–867. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Josso N. Development and descent of the fetal testis. In: Bierich J.L., Rager K., Ranke, editors. Maldescensus Testis. Urban and Schwarzenberg; Munich: 1977. pp. 3–11. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hutson J.M. Undescended testis: the underlying mechanisms and the effects on germ cells that cause infertility and cancer. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2013;48:903–908. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2013.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Josso N., Rey R., Picard J.Y. Testicular anti-Mullerian hormone: clinical applications in DSD. Semin. Reprod. Med. 2012;30:364–373. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1324719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nishi M.Y. Analysis of anti-Mullerian hormone (AMH) and its receptor (AMHR2) genes in patients with persistent Mullerian duct syndrome. Arq. Bras. Endocrinol. Metabol. 2012;56:473–478. doi: 10.1590/s0004-27302012000800002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Salehi P. Persistent Mullerian duct syndrome: 8 new cases in Southern California and a review of the literature. Pediatr. Endocrinol. Rev. 2012;10:227–233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Taguchi O., Cunha G.R., Lawrence W.D. Timing and irreversibility of müllerian duct inhibition in the embryonic reproductive tract of the human male. Dev. Biol. 1984;106:394. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(84)90238-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Klattig J., Englert C. The Mullerian duct: recent insights into its development and regression. Sex Dev. 2007;1:271. doi: 10.1159/000108929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Picard J.Y., Belville C. Genetics and molecular pathology of anti-Mullerian hormone and its receptor. J. Soc. Biol. 2002;196:217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Colacurci N. Laparoscopic hysterectomy in a case of male pseudohermaphroditism with persistent Mullerian duct derivatives. Hum. Reprod. 1997;12:272–274. doi: 10.1093/humrep/12.2.272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hutson J.M., Baker M.L. A hypothesis to explain abnormal gonadal descent in persistent Mullerian duct syndrome. Pediatr. Surg.Int. 1994;9:542–543. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Imbeaud S. Testicular degeneration in three patients with the persistent Mullerian duct syndrome. Eur. J. Pediatr. 1995;154:187–190. doi: 10.1007/BF01954268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Josso N. The persistent Mullerian duct syndrome: a rare cause of cryptorchidism. Eur. J. Pediatr. 1993;152:S76–S78. doi: 10.1007/BF02125444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shinmura Y., Yokoi T., Tsutsui Y. A case of clear cell adenocarcinoma of the mullerian duct in persistent mullerian duct syndrome: the first reported case. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2002;26:1231–1234. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200209000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Farikullah J., Ehtisham S., Nappo S. Persistent Mullerian duct syndrome: lessons learned from managing a series of eight patients over a 10-year period and review of literature regarding malignant risk from the Mullerian remnants. BJU Int. 2012;110:1084–1089. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2012.11184.x. Epub 2012 Apr 30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Telli O., Gökçe M.I., Haciyev P., Soygür T., Burgu B. Transverse testicular ectopia: a rare presentation with persistent müllerian duct syndrome. J. Clin. Res. Pediatr. Endocrinol. 2014;6:180–182. doi: 10.4274/jcrpe.1479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Esteves Edward, Pinus Jaques, de Albuquerque Maranhao Renato Frota. Sao Paulo Med. J./ RPM. 1995;113(4):935–940. doi: 10.1590/s1516-31801995000400003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Agha R.A., Fowler A.J., Saetta A., Barai I., Rajmohan S., Orgill D.P., the SCARE Group The SCARE Statement: consensus-based surgical case report guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2016;34:180–186. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2016.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.