Abstract

The MCM2-MCM7 complex is an essential component of the prereplication complex (pre-RC), which is recruited by the cdc6 and cdt1 proteins to origins of DNA replication during G1 phase. Here, we report that the accumulation on chromatin of another member of the MCM protein family, human MCM8 (hMCM8), occurs during early G1 phase, before the hMCM2-hMCM7 complex binds. hMCM8 interacts in vivo with two components of the pre-RC, namely, hcdc6 and hORC2. Depletion of endogenous hMCM8 protein by RNA interference leads to a delay of entry into S phase, suggesting a role for hMCM8 in G1 progression. Furthermore, down-regulation of hMCM8 also leads to a reduced loading of hcdc6 and the hMCM2-hMCM7 complex on chromatin. These results suggest that hMCM8 is a crucial component of the pre-RC and that the interaction between hMCM8 and hcdc6 is required for pre-RC assembly.

Replication of DNA must be inherently accurate and precisely regulated. Initiation of DNA replication in eukaryotic cells is a strictly controlled process so that chromosomal DNA is duplicated only once per cell cycle. This process is cell cycle regulated, requiring the assembly of a prereplicative complex (pre-RC) in G1 phase (4, 24, 31). The pre-RC contains several conserved initiation proteins and assembles before DNA synthesis. In eukaryotes, initiation starts with the assembly of a six-subunit origin recognition complex (ORC) at the origin, with ORC serving as a platform on which the pre-RC is assembled. ORC is essential for initiation, and it remains bound to replication origins throughout the cell cycle in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Schizosaccharomyces pombe (5, 13, 28) but is highly dynamic in mammalian cells (11). In human cells, the chromatin association of the ORC subunit, ORC1, is cell cycle regulated, and the integral component of the core of ORC, ORC2, is bound to chromatin throughout the cell cycle, according to biochemical-fractionation and immunoblotting studies (27, 30, 32, 35, 39). Surprisingly, recent studies of the localization of ORC2 by an immunofluorescence assay suggest that the chromatin association of ORC2 is dynamic throughout interphase (38).

After binding to origin DNA, ORC recruits two other proteins, cdc6 and cdt1. The binding of cdc6 to origins may lead to stabilization of ORC binding to chromatin (34). ORC, cdc6, and cdt1 then cooperate to load the minichromosome maintenance (MCM) complex on chromatin in an ATP-dependent manner. Once replication begins, cdc6 is degraded in yeast (37) by the anaphase-promoting complex (36). In metazoans, levels of chromatin-bound cdc6 vary, being low in early G1 and then accumulating until cells enter mitosis (1, 10).

The MCM hexamer consists of the MCM2-MCM7 complex proteins (2, 8, 12), which are structurally related and highly conserved in eukaryotes. In vivo and in vitro studies have revealed that, in addition to the heterohexameric form, the proteins can form additional complexes with different combinations of the MCM proteins (25, 43). Biochemical analysis of the MCM complex showed that the human and fission yeast MCM4-MCM6-MCM7 complex contains DNA helicase activity in vitro (20, 26). Initiation of DNA replication is triggered by the cooperative action of at least two sets of protein kinases, cyclin-dependent kinases and Dbf4-Cdc7, which recruit cdc45 to origins of DNA replication (48). There is also good evidence that Cdc7 stimulates initiation by phosphorylating MCM2 (41). MCM proteins are essential for DNA replication and have been implicated in licensing DNA for replication in Xenopus egg extracts (7, 29). Replication origins that are no longer occupied by the MCM complex are inactive, and this period of inactivation persists into the next G1 phase, in which a new cycle of activity begins with the recruitment of the MCM2-MCM7 complex.

Besides binding to cdc45, the MCM2-MCM7 complex also interacts with another replication initiation factor, MCM10, that is required for chromosomal DNA replication and stable plasmid maintenance in S. cerevisiae (33). Homologues of this gene have been identified in other organisms, including S. pombe, Xenopus laevis, and humans (3, 21, 45). In S. cerevisiae, MCM10 is a component of the pre-RC and is required for the association of the MCM complex with origin DNA (19). In S. cerevisiae and S. pombe, MCM10 is constitutively chromatin bound (16, 19). The binding of Xenopus MCM10, however, is not required for origin binding of Xenopus MCM2-MCM7 (45). Instead, the chromatin binding of MCM2-MCM7 is required for the chromatin association of MCM10, which in turn facilitates the binding of cdc45 to origins. Human MCM10 binds chromatin at the G1- to S-phase transition, but its function in the regulation of chromatin binding of the MCM2-MCM7 hexamer is not clear (22).

Another MCM family member, MCM8, contains the typical MCM domain and functional motifs of the MCM2-MCM7 proteins. Unlike MCM2-MCM7 and MCM10, MCM8 does not have a direct counterpart in yeast but is expressed in several higher eukaryotes (15).

In this paper, we show that human MCM8 (hMCM8) binds to chromatin during the cell cycle. Down-regulation of endogenous hMCM8 with small hairpin RNAs (sh-RNAs) in HeLa cells interferes with their ability to enter S phase. Furthermore, we found that human MCM8 interacts with two components of the pre-RC, hORC2 and hcdc6. In addition, inhibition of hMCM8 function by RNA interference (RNAi) leads to a reduced binding of hcdc6 to chromatin, suggesting an important function for hMCM8 in the assembly of the pre-RC.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmids.

hMCM8 was purchased as an IMAGE clone (clone identification number, IMAGp958J15244) from the German Resource Center for Genome Research. Two stop codons in front of the start ATG were removed, and a new BamHI site was introduced by PCR. The 3.1-kb BamHI-BglII full-length hMCM8 from pOTB7 was cloned into pRSET-B (Invitrogen) or pTriEX (Novagen) with or without a hemagglutinin (HA) tag, respectively. After the introduction of two nucleotides by use of the QuikChange kit (Stratagene), hMCM8 was cloned, by using BamHI-BglII, into pGEX-4T-3 (Amersham). A stop codon was introduced 92 amino acids after the start methionine, again by using the QuikChange kit, to produce a glutathione S-transferase (GST)-hMCM8 fragment in an Escherichia coli strain for raising a rabbit polyclonal antibody.

Antibodies.

To generate the N-terminal anti-hMCM8 polyclonal antibody [MCM8(1-92)], a fragment of hMCM8 (amino acids 1 through 92) was overexpressed in E. coli and purified as a GST-tagged fusion protein by using glutathione Sepharose (Sigma). Immunization of the rabbit was done by C. River. The C-terminal antibody [MCM8(741-756)] was raised against a synthetic peptide corresponding to amino acids 741 through 756 conjugated to keyhole limpet hemocyanin. The peptide synthesis and immunization of the rabbit were performed by Innovagen (Lund, Sweden). The terminal blood samples containing both antibodies were further purified on affinity columns. Anti-hORC2 was a kind gift from B. Stillman (Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.). Anti-hMCM10 was kindly provided by F. Hanaoka (Institute for Molecular and Cellular Biology and CREST, Osaka University, Osaka, Japan). Anti-cyclin B was used as previously described (18). Antibodies to MEK1 and MEK2 were obtained from BioLabs, and anti-hMCM2 (N-19), anti-hMCM3 (G-19), anti-hMCM6 (C-20), and anti-hcdc6 (180.2) were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, Calif.). Anti-hPAN-MCM was purchased from BD PharMingen, and the monoclonal antibody 3F10 (anti-HA) was from Roche.

Cell culture and cell manipulations.

The cell lines HeLa, Hs68, and 293T were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. HeLa cells were synchronized in S phase by treatment with 10 mM hydroxyurea (Sigma) and were harvested 18 h later by trypsinization. To synchronize HeLa cells at prometaphase, cells were treated with 50 ng of nocodazole (Sigma)/ml for 12 h. Cells were harvested by mitotic shake-off or released from a nocodazole block by being washed five times in medium without nocodazole and were then reseeded into fresh medium. For a G1-phase population, cells were harvested 8 h after their release from the block. The remaining cells after the mitotic shake-off were harvested by trypsinization to obtain cells in G2 phase. For time course studies, cells were harvested at the indicated time points after nocodazole release, washed once in phosphate-buffered saline, and used to prepare total cell extracts or subjected to biochemical fractionation, as described previously (30). For cytofluorometric analysis of DNA content, an aliquot of 2 × 105 cells was fixed in 70% ethanol. After fixation overnight at −20°C, cells were collected by centrifugation and treated with RNase (50 mM Tris-HCl at pH 7.5, 10 mM MgCl2, 10 μg of RNase A [Roche]/ml) for 30 min at 37°C. The cells were stained overnight on ice with propidium iodide (35 μg/ml, Sigma). Stained cells were analyzed with a Becton Dickinson FACScan. The data were analyzed with Cellquest software (Becton Dickinson).

Immunoblots and immunoprecipitations.

For Western blotting, cells were lysed in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 250 mM NaCl, 0.1% Triton X-100, 5 mM EDTA, 50 mM NaF) supplemented with protease inhibitors (aprotinin, leupeptin, soybean trypsin inhibitor, TPCK [tosylsulfonyl phenylalanyl chloromethyl ketone], TLCK, [Nα-p-tosyl-l-lysine chloromethyl ketone], and phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride) for 30 min on ice, followed by centrifugation at 15,000 × g for 10 min, or they were subjected to biochemical fractionation (30). Extracts were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). A standard protocol for immunoblotting was used (17), and antibodies were used according to the manufacturer's instructions. Both anti-MCM8(1-92) and anti-MCM8(741-756) antibodies were used in a 1:1,000 dilution (0.2 μg/ml). For immunoprecipitations, 293T cells were transfected by using the standard calcium phosphate transfection protocol and harvested 36 h later. Cells were lysed, as described by Sommer et al. (42), in L buffer (140 mM NaCl, 2.6 mM KCl, 2 mM Na2HPO4, 1.45 mM KH2PO4, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.5% aprotinin, 50 mM β-glycerolphosphate, 10 mM NaF), supplemented with 50 U of RNase-free DNase I (Roche)/ml and 5 mM MgCl2, incubated on ice for 30 min, and cleared by centrifugation at 18,000 × g. Extracts were incubated overnight (at 4°C with rotation) with protein G-Sepharose (Pharmacia) and anti-HA antibody and then washed three times with L buffer. Beads were resuspended in SDS sample buffer, boiled for 10 min, and subjected to SDS-PAGE, followed by immunoblotting. For immunoprecipitation of endogenous proteins, HeLa cells were lysed in L buffer (42) supplemented with 50 U of DNase I/ml and 5 mM MgCl2, incubated on ice for 60 min, and cleared by centrifugation. MCM8 was immunoprecipitated by using the anti-MCM8(741-756) antibody. As a negative control, anti-MCM8(741-756) was preincubated with a 1,000 molar excess of the corresponding antigenic peptide for 15 min at room temperature.

RNA interference.

The MCM8 targeting vector was based on a 19-mer sequence present in the coding sequence of human MCM8 (AGCGATAGCTCTCCTTTGA). Firefly luciferase (GL2) (14) was used as a control. Synthetic 64-mer oligonucleotides for cloning into pSuper (pS) were synthesized, annealed, and ligated into the pS construct as described previously (6). Cells were transfected by using the standard calcium phosphate transfection protocol. Where indicated for Fig. 5, cells were synchronized for 12 h with nocodazole at 60 h after transfection or were harvested at 48, 60, and 72 h after transfection and subjected to biochemical fractionation.

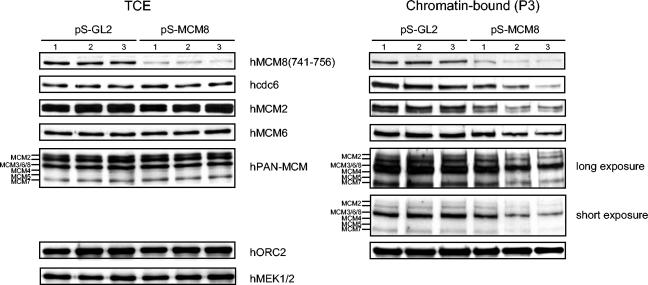

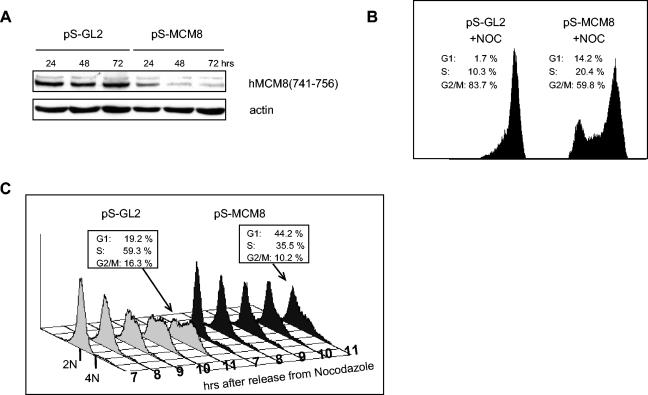

FIG. 5.

Loading of hcdc6 and hMCM proteins on chromatin is reduced after the down-regulation of hMCM8. Cells were transfected with pS-GL2 or pS-MCM8, harvested 48 (lane 1), 60 (lane 2), and 72 (lane 3) h later, and subjected to the biochemical-fractionation method as described in the legend to Fig. 2. Immunoblotting was carried out for total cell extract (TCE) (left panel) and the chromatin fraction (P3) (right panel) with antibodies against the indicated proteins. MEK1/MEK2, a cytosolic protein kinase, was used as a control.

RESULTS

Chromatin binding of MCM8 is cell cycle regulated.

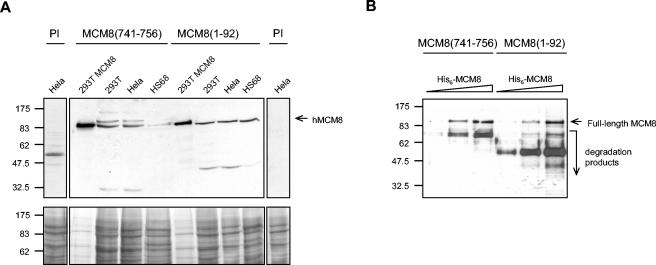

To study the role of hMCM8, two polyclonal antibodies were raised in rabbits against an N-terminal fragment of hMCM8 as a GST fusion and a C-terminal peptide sequence. Each of the resulting affinity-purified antisera denoted MCM8(1-92) and MCM8(741-756) specifically recognized a 93-kDa band in unfractionated extracts of 293T cells, HeLa cells, and Hs68 human foreskin fibroblasts whose intensity increased following the expression of recombinant MCM8 in 293T cells (Fig. 1A). A slower-migrating band was also observed with anti-MCM8(741-756) but was absent in immunoprecipitates with the same antibody (Fig. 3B) and in immunoblots with MCM8(1-92). This particular band was not down-regulated in response to RNAi and might be a cross-reactive band. Preimmune control antibodies gave negative Western blot results. Both antibodies also recognized His6-tagged MCM8 in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1B). Neither of the MCM8 antibodies showed cross-reactivity with the MCM2-MCM7 complex proteins or MCM10 (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Characterization of polyclonal antibodies generated against hMCM8. (A) Total cell extracts of HeLa, 293T (untransfected or transfected with hMCM8), and HS68 cells were subjected to SDS-PAGE, and proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose. After protein staining with Ponceau-S red (lower panel), the blot was cut and immunoblotted with either the C-terminal antibody [MCM8(741-756)], the N-terminal antibody [MCM8(1-92)], or the corresponding preimmune sera (PI) (upper panel). (B) Increasing amounts of recombinant His6-tagged hMCM8 (200, 400, and 800 ng) were subjected to SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose, and immunoblotted with the polyclonal antibodies anti-hMCM8(1-92) and anti-hMCM8(741-756). Molecular mass markers (in kilodaltons) are noted at the left.

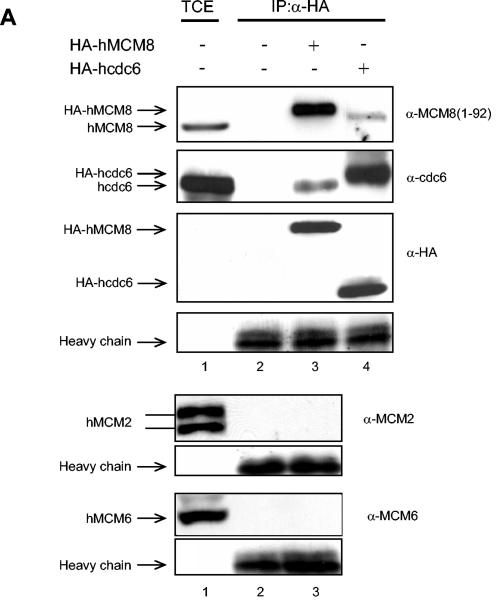

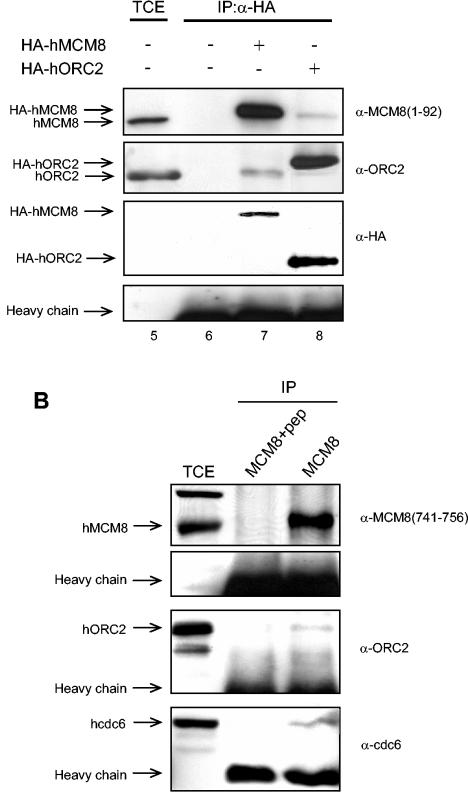

FIG. 3.

hMCM8 interacts with hcdc6 and hORC2 but not with the hMCM2-hMCM7 complex. (A) 293T cells were transfected with either HA-tagged hMCM8 (lanes 3 and 7), HA-tagged hcdc6 (lane 4), or HA-tagged ORC2 (lane 8). Untransfected 293T cells served as negative controls (lanes 2 and 6). Total cell extract of untransfected 293T cells (TCE) was used as the input control (lanes 1 and 5). Untransfected and transfected cells were incubated with anti-HA antibodies (α-HA) overnight. Immunoprecipitates (IP) were subjected to SDS-PAGE, and immunoblotting was carried out with the indicated antibodies. (B) HeLa cells were lysed and incubated with anti-MCM8(741-756) antibodies (MCM8) or anti-MCM8(741-756) antibodies preincubated with the corresponding antigenic peptide (MCM8+pep). Immunoprecipitates were subjected to SDS-PAGE and probed in immunoblots with the indicated antibodies.

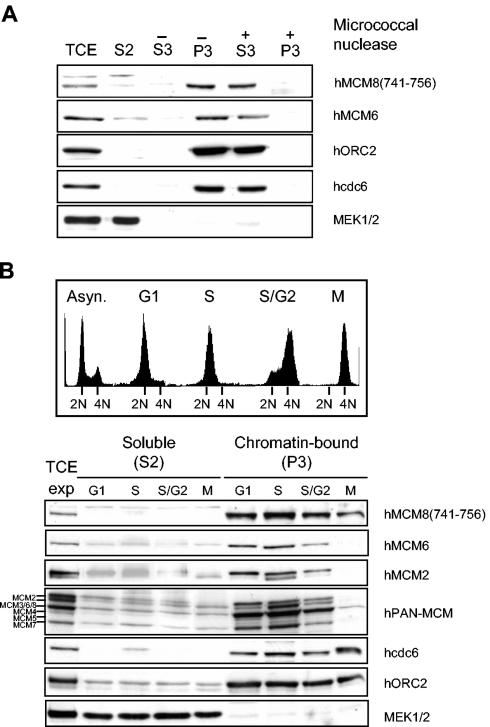

The localization of the MCM2-MCM7 hexamer is tightly regulated during the cell cycle (46). To exactly assess the regulation of human MCM8, we first analyzed its chromatin binding in comparison to that of known replication initiation proteins. Using a simple biochemical-fractionation method developed by Méndez and Stillman (30), we compared the chromatin binding of hMCM8 to that of hMCM6, hORC2, and hcdc6 proteins (Fig. 2A). The pre-RC components hORC2 and hcdc6 were detected only in the chromatin-bound fraction (Fig. 2A, lane −P3), similar to results reported previously (30), whereas hMCM6 and hMCM8 were present in the chromatin-bound fraction and, to a lesser extent, also in the soluble fraction (Fig. 2A, lane S2). MEK1/MEK2, a cytosolic protein kinase, was used as a control and was shown to be present only in the cytosolic fraction (Fig. 2A, lane S2). Solubilization of chromatin-bound proteins with micrococcal nuclease (Fig. 2A, lane +S3) demonstrated that hMCM8 is associated with chromatin and not with the nuclear matrix. To test whether the chromatin association of hMCM8 is regulated during the cell cycle, we prepared chromatin-bound and soluble fractions from HeLa cells synchronized at different stages of the cell cycle. Flow cytometry confirmed the synchrony of the samples (Fig. 2B, upper panel). hORC2 was bound to chromatin at equal levels in each phase of the cell cycle, similar to results described previously (30). We found hMCM8 bound to chromatin throughout the cell cycle (Fig. 2B, lower panel). The PAN-MCM antibody also recognizes hMCM8 at 93 kDa and confirms the presence of MCM8 on chromatin during mitosis (Fig. 2B, lower panel). A binding profile similar to that of chromatin was also found for hcdc6. In contrast, hMCM6 and hMCM2 were bound to chromatin only from G1 to early G2 phase (Fig. 2B, lower panel). They were absent during mitosis, and they reassociated with chromatin in early G1 phase. From the data presented in Fig. 2B, we cannot exclude the possibility that hMCM8 also dissociates from chromatin during the transition from metaphase to G1 phase. Therefore, we analyzed in more detail the chromatin association of hMCM8 in cells that have been released from the nocodazole block and monitored them up to early G1 phase. The DNA content of each fraction was determined by staining with propidium iodide, and the percentage of cells in each phase of the cell cycle was calculated (Fig. 2C, upper panel). As shown in Fig. 2C (lower panel), hORC2 was constantly bound at the same protein level to chromatin, whereas hcdc6 accumulated at the M- to G1-phase transition. Both hMCM6 and hMCM3 reassociated with chromatin at 60 min after nocodazole release, while hMCM2 re-bound chromatin later at 150 min after release from the nocodazole block. MCM10 associated with chromatin at the same time as MCM2. In contrast, a small fraction of hMCM8 was bound to chromatin at prometaphase and kept accumulating from late mitosis to early G1 phase (Fig. 2C). In conclusion, our data imply that hMCM8 binds to chromatin before components of the hMCM2-hMCM7 complex and hMCM10 associate and prior to the formation of the pre-RC.

FIG. 2.

hMCM8 is chromatin bound, and its chromatin binding is cell cycle regulated. (A) Asynchronous HeLa cells were subjected to a biochemical fractionation. In brief, cells were lysed with Triton X-100 in a sucrose-rich buffer. Cytoplasmic proteins (S2) were separated from the nuclei by low-speed centrifugation. Nuclei were washed and then lysed in a no-salt buffer. A second centrifugation step separated the remaining soluble nuclear proteins (S3) from an insoluble fraction (P3). Proteins found in the final pellet (P3) were likely to be bound to chromatin or the nuclear matrix. The distributions of different proteins in the total cell extract (TCE), soluble fraction (S2), solubilized nuclear proteins (S3), and chromatin-enriched fraction (P3), with or without micrococcal nuclease treatment (+ or −), are shown. (B) Chromatin association of hMCM8, the MCM2-MCM7 complex, hcdc6, and hORC2 during the cell cycle. HeLa cells were arrested at different stages of the cell cycle, the DNA content was determined by flow cytometry (upper panel), and an aliquot of cells was subjected to biochemical fractionation. Immunoblots of the soluble and insoluble fractions are shown (lower panel). The total cell extract of exponentially growing cells (TCE exp) was used as the input control. (C) Chromatin association of hMCM8 at the M- to G1-phase transition. HeLa cells were synchronized at prometaphase with nocodazole and then harvested by mitotic shake-off. Cells were collected at different time points after release from the block and subjected to biochemical fractionation (lower panel). The DNA contents of cells harvested at the indicated time points were determined by flow cytometry (upper panel).

Interaction of hMCM8 with hcdc6 and hORC.

Cdc6 and ORC are essential components of the pre-RC at origins of replication which are assembled before the initiation of DNA replication. Since we found that the chromatin binding of hMCM8 parallels that of hcdc6 and hORC2, we then wished to analyze whether human MCM8 interacts with these two components of the pre-RC. We therefore performed coimmunoprecipitation experiments. 293T cells were left untransfected or were transfected with HA-hMCM8, HA-hcdc6, or HA-hORC2. Proteins were immunoprecipitated with anti-HA antibodies, and the presence of associated proteins was determined by immunoblot analysis with specific antibodies against hMCM8, hcdc6, or hORC2. In cells transfected with HA-hMCM8, we found that both endogenous hcdc6 and hORC2 coimmunoprecipitated with HA-hMCM8 (Fig. 3A, lanes 3 and 7). Reciprocally, overexpressed HA-hcdc6 or HA-hORC2 coimmunoprecipitated endogenous hMCM8 protein (Fig. 3A, lanes 4 and 8). We did not detect an association of HA-hMCM8 with hMCM2-hMCM7 complex proteins (Fig. 3A, lane 3). To test whether endogenous hMCM8 interacts with endogenous hcdc6 and hORC2, we carried out immunoprecipitations in HeLa cell extracts by using hMCM8(741-756) antibodies in the presence and absence of the corresponding antigenic peptide and probed these in Western blots with antibodies against hcdc6 and hORC2. We found that hMCM8 specifically interacts with both hcdc6 and hORC2 but that in the presence of antigenic peptide, no interaction occurred (Fig. 3B). Taken together, these results suggest that hMCM8 forms complexes in vivo with both hcdc6 and the hORC complex.

RNAi-mediated down-regulation of hMCM8 impairs the G1-to-S transition.

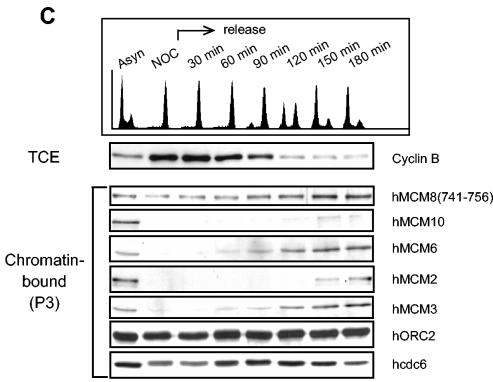

Since we observed hMCM8 associating with chromatin and interacting with components of the pre-RC, we asked whether hMCM8 function would be required for assembly of the pre-RC. We therefore determined whether down-regulation of endogenous hMCM8 by RNAi would prevent cells from entering S phase. To test this, we depleted hMCM8 mRNA in HeLa cells by using a vector that expressed sh-RNAs (6). Down-regulation was specific for hMCM8, since protein levels of other MCM family members were not affected (Fig. 5). Transfection of MCM8 sh-RNA (pS-MCM8) but not of the control vector (pS-GL2) resulted in a reduction of hMCM8 protein levels in Western blots with the MCM8(741-756) antibody, leading to a quantitative decrease of around 80% in the amount of endogenous hMCM8 protein at 72 h after transfection (Fig. 4A). We then analyzed by FACScan whether RNAi-mediated down-regulation of hMCM8 would lead to an increase in the amount of cells in G1 phase. We did, however, find only a small difference between the cell cycle distribution in pS-hMCM8 cells and that in control transfected cells (data not shown). Therefore, we studied the effect of hMCM8 down-regulation in synchronized cell populations. HeLa cells were transfected with pS-MCM8 or pS-GL2, treated with nocodazole to prevent reentry of the transfected cells into G1, and then analyzed by flow cytometry (Fig. 4B). The numbers indicate the amounts of cells in G1, S, or G2/M phase. It is conceivable that cells lacking hMCM8 function failed to enter prometaphase, most likely because they are not able to pass the G1- to S-phase transition. In fact, around 14% of the cell population remained in G1 phase after transfection of pS-hMCM8, whereas only 2% of the control transfected cells were found in G1. A significant population of the cells was also found in S phase in response to hMCM8 silencing (20% in MCM8-silcenced cells versus 10% in control cells). This outcome might be due to the possibility that cells that were not transfected with small hairpin MCM8 and therefore were not arrested in G1 or, alternatively, that they escaped the block because of residual amounts of MCM8. However, we cannot rule out the possibility that hMCM8 plays an additional role during S-phase progression. To further explore the function of hMCM8 at the G1- to S-phase transition, we performed an experiment similar to the one described in the legend to Fig. 4B, but this time, a time course experiment was carried out. HeLa cells were transfected with either pS-GL2 or pS-MCM8. At 60 h after transfection, cells were treated for 12 h with nocodazole, harvested by mitotic shake-off, washed five times, and reseeded into fresh medium. Samples were taken at indicated time points (Fig. 4C). We found that after removing the drug, cells in which hMCM8 was down-regulated passed the G1- to S-phase transition at a slower kinetics than control cells (Fig. 4C). In fact, while 44% of the hMCM8-silenced cells remained in G1 at 11 h after release from the block in control cells, only 19% remained in G1. These findings suggest that hMCM8 fulfills a role in G1 phase, since cells lacking the protein enter S phase with a significantly reduced kinetics. The fact that not all cells showed a block in G1 after the silencing of hMCM8 may be due to the incomplete down-regulation of hMCM8 protein levels following RNAi (Fig. 4A).

FIG. 4.

Down-regulation of hMCM8 by RNAi impairs the G1-to-S transition. (A) HeLa cells were transfected with either pS-MCM8 or pS-GL2, and the levels of hMCM8 were determined by immunoblotting at the indicated time points after transfection. (B) RNAi-mediated down-regulation of hMCM8 delays the G1-to-S transition. HeLa cells were transfected with either pS-GL2 or pS-MCM8, treated with nocodazole for 12 h at 60 h after transfection to prevent reentry of the transfected cells into G1, and analyzed by flow cytometry. (C) Down-regulation of hMCM8 leads to a delay in entry into S phase. HeLa cells were transfected with either pS-GL2 or pS-MCM8 and treated for 12 h with nocodazole. At 72 h after transfection, cells were harvested by mitotic shake-off, washed five times, and reseeded into fresh medium. Samples were taken at the indicated time points after release from the nocodazole block, and the DNA contents were determined by flow cytometry.

hMCM8 is required for chromatin association of hcdc6.

In yeast, the replication initiation factor MCM10 is required for the association of the MCM2-MCM7 complex with origins of replication to generate the pre-RC (19, 33), but recent data also suggest that MCM10 may function after pre-RC formation, before or concomitant with the recruitment of cdc45 (40). Experiments performed with Xenopus also indicate that MCM10 functions beyond pre-RC assembly and suggest that it binds to origins of DNA replication after MCM2-MCM7 has bound (45). In Xenopus, the interaction between MCM10 and cdc45 also facilitates the recruitment of cdc45 to the pre-RC (45). To determine at which step of replication initiation hMCM8 functions, we carried out fractionation experiments with hMCM8-silenced HeLa cells with a time course of 48, 60, and 72 h after transfection of sh-RNAs (Fig. 5). Chromatin fractionation was performed as described in the legend to Fig. 2, and the chromatin binding of several components of the pre-RC was analyzed. We found a pronounced down-regulation of the levels of the human cdc6 protein associated with chromatin in hMCM8-silenced cells (Fig. 5, right panel). Moreover, with anti-MCM2, anti-MCM6, and anti-PAN-MCM antibodies, a slight down-regulation of the levels of the MCM2-MCM7 complex proteins that bound to chromatin upon silencing of hMCM8 was also observed, although no direct interaction between hMCM2-hMCM7 and hMCM8 could be detected (Fig. 3A). We can exclude the possibility that the reduction observed in hcdc6 and hMCM2-hMCM7 complex binding results from a G2 delay, since cell cycle progression is not affected in hMCM8-silenced cells (data not shown). Despite the fact that hMCM8 interacts with ORC, no reduction of chromatin-bound hORC2 levels in response to hMCM8 silencing occurred, suggesting that hMCM8 does not regulate the binding of hORC2 to chromatin. Down-regulated hMCM10 revealed that no reduction in the levels of components of the pre-RC occurred (data not shown). Our results therefore indicate that human MCM10 is not involved in pre-RC formation. Since hMCM8 interacts in vivo with hcdc6 and its down-regulation leads to reduced binding of hcdc6 to chromatin, we suggest that hMCM8 might act as a factor that mediates the recruitment of hcdc6 to chromatin, leading subsequently to the loading of the hMCM2-hMCM7 complex and initiation of DNA replication.

DISCUSSION

The loading mechanism of the different pre-RC components at the origin and the detailed mechanism of replication initiation in human cells are not yet well understood. We have analyzed the function of human MCM8 in the assembly of the pre-RC. hMCM8 forms a complex with both hcdc6 and hORC and is required for loading of hcdc6 to chromatin.

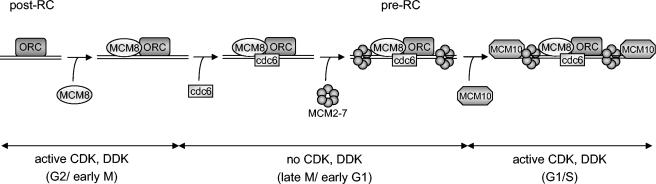

Whereas chromatin binding of the hMCM2-hMCM7 complex occurs only from G1 to early G2 phase, hMCM8 is bound to chromatin throughout the cell cycle (Fig. 2B). As previously shown by Gozuacik et al. (15) and as shown by this study (Fig. 3A), hMCM8 does not seem to interact directly with the hMCM2-hMCM7 complex in coimmunoprecipitation experiments, while other published data indicate that hMCM8 does associate with the hMCM2-hMCM7 complex proteins (23). This discrepancy might be explained by the use of different antibodies and buffer compositions. The facts that cdc6 is required for loading MCM2-MCM7 to chromatin (9, 44) and that a reduction of the amount of hMCM2-hMCM7 loaded onto chromatin was also observed upon down-regulation of hMCM8 by sh-RNAs (Fig. 5) lead us to conclude that a loose binding of hMCM8 to the hMCM2-hMCM7 complex might not be direct but rather mediated through hcdc6. Based on these findings, we present a model for human MCM8 function. At the end of mitosis, hMCM8 associates with hORC. hMCM8 then, in turn, recruits hcdc6 to origins of replication, possibly in cooperation with hcdt1. hcdc6 is required for the recruitment of the hMCM2-hMCM7 complex, resulting in the assembly of the pre-RC (Fig. 6). In a later step, the replicative helicase activity of the hMCM2-hMCM7 complex is induced through phosphorylation of the complex by two kinases, cdk2/cyclin E and cdc7/Dbf4. Then, hMCM10 also attaches to the complex and leads to the recruitment of cdc45 and other replication factors (Fig. 6).

FIG. 6.

Model describing the function of MCM8 as a loading factor for cdc6 to chromatin in human cells. See the text for details.

hMCM8 is an evolutionarily conserved protein with homologues in Drosophila melanogaster, X. laevis, and Mus musculus (15). No homologues of hMCM8 have been identified in yeast and Caenorhabditis elegans. Since cdc6 is also required for MCM2-MCM7 loading in yeast, the question remains as to how the loading of cdc6 itself is regulated in this organism. In a yeast genetic screen, a novel replication-initiation protein, Noc3p, has been identified (47). Noc3p binds chromatin and autonomously replicating sequence elements throughout the cell cycle, and together with the ORC, it functions at replication origins to recruit cdc6p and MCM proteins for the establishment of the pre-RCs. Our own data suggest that hMCM8 might take over the role of Noc3 in higher eukaryotic cells. However, Noc3 itself is also present in higher eukaryotic cells, but its characterization remains elusive. It would therefore be intriguing to investigate if human Noc3 regulates hMCM8 function or vice versa. It is also conceivable that both proteins act in different cellular pathways to recruit hcdc6 to chromatin.

The execution point of MCM10 during the initiation of DNA replication has been a matter of debate. In S. cerevisiae, MCM10 is involved in the assembly of pre-RC by recruiting the MCM2-MCM7 complex and anchoring it to origins of DNA replication (19). Very recent results from the same group indicate that MCM10 also functions after pre-RC formation by recruiting cdc45 (40). Biochemical experiments with Xenopus MCM10 reveal that the protein clearly associates with chromatin after MCM2-MCM7 has bound (45) and is also required for the recruitment of cdc45 in this organism. We found that in human cells, hMCM10 is loaded to chromatin later than the hMCM2-hMCM7 complex (Fig. 2C). In addition, inhibition of hMCM10 function by RNAi does not lead to a reduction in the binding of hMCM2-hMCM7 to chromatin (data not shown), suggesting that in human cells, MCM10 is not involved in pre-RC formation. Our results suggest that human MCM8 participates in the activation of the pre-RC during G1 phase by recruiting cdc6 to the origin of DNA replication and that binding of cdc6 is required for origin binding of MCM2-MCM7. In the future, it will be intriguing to determine if hMCM8 is also required for the loading of Cdt1 to chromatin and how its function as a component of the pre-RC is regulated.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Fumio Hanaoka for providing antiserum against human MCM10 and Bruce Stillman for supplying Cdc6 and ORC2 expression plasmids and antiserum against human ORC2. We thank the members of our lab for discussion and Irina Kotova for critically reading the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alexandrow, M. G., and J. L. Hamlin. 2004. Cdc6 chromatin affinity is unaffected by serine-54 phosphorylation, S-phase progression, and overexpression of cyclin A. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24:1614-1627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aparicio, O. M., D. M. Weinstein, and S. P. Bell. 1997. Components and dynamics of DNA replication complexes in S. cerevisiae: redistribution of MCM proteins and Cdc45p during S phase. Cell 91:59-69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aves, S. J., N. Tongue, A. J. Foster, and E. A. Hart. 1998. The essential Schizosaccharomyces pombe cdc23 DNA replication gene shares structural and functional homology with the Saccharomyces cerevisiae DNA43 (MCM10) gene. Curr. Genet. 34:164-171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bell, S. P., and A. Dutta. 2002. DNA replication in eukaryotic cells. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 71:333-374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bell, S. P., and B. Stillman. 1992. ATP-dependent recognition of eukaryotic origins of DNA replication by a multiprotein complex. Nature 357:128-134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brummelkamp, T. R., R. Bernards, and R. Agami. 2002. A system for stable expression of short interfering RNAs in mammalian cells. Science 296:550-553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chong, J. P., H. M. Mahbubani, C. Y. Khoo, and J. J. Blow. 1995. Purification of an MCM-containing complex as a component of the DNA replication licensing system. Nature 375:418-421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cocker, J. H., S. Piatti, C. Santocanale, K. Nasmyth, and J. F. Diffley. 1996. An essential role for the Cdc6 protein in forming the pre-replicative complexes of budding yeast. Nature 379:180-182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cook, J. G., D. A. Chasse, and J. R. Nevins. 2004. The regulated association of Cdt1 with minichromosome maintenance proteins and Cdc6 in mammalian cells. J. Biol. Chem. 279:9625-9633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coverley, D., C. Pelizon, S. Trewick, and R. A. Laskey. 2000. Chromatin-bound Cdc6 persists in S and G2 phases in human cells, while soluble Cdc6 is destroyed in a cyclin A-cdk2 dependent process. J. Cell Sci. 113:1929-1938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.DePamphilis, M. L. 2003. The ‘ORC cycle’: a novel pathway for regulating eukaryotic DNA replication. Gene 310:1-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Diffley, J. F. 1994. Eukaryotic DNA replication. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 6:368-372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Diffley, J. F., J. H. Cocker, S. J. Dowell, and A. Rowley. 1994. Two steps in the assembly of complexes at yeast replication origins in vivo. Cell 78:303-316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elbashir, S. M., J. Harboth, W. Lendeckel, A. Yalcin, K. Weber, and T. Tuschl. 2001. Duplexes of 21-nucleotide RNAs mediate RNA interference in cultured mammalian cells. Nature 411:494-498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gozuacik, D., M. Chami, D. Lagorce, J. Faivre, Y. Murakami, O. Poch, E. Biermann, R. Knippers, C. Brechot, and P. Paterlini-Brechot. 2003. Identification and functional characterization of a new member of the human Mcm protein family: hMcm8. Nucleic Acids Res. 31:570-579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gregan, J., K. Lindner, L. Brimage, R. Franklin, M. Namdar, E. A. Hart, S. J. Aves, and S. E. Kearsey. 2003. Fission yeast Cdc23/Mcm10 functions after pre-replicative complex formation to promote Cdc45 chromatin binding. Mol. Biol. Cell 14:3876-3887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harlow, E., and D. Lane. 1999. Using antibodies, a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 18.Hoffmann, I., G. Draetta, and E. Karsenti. 1994. Activation of the phosphatase activity of human cdc25A by a cdk2-cyclin E dependent phosphorylation at the G1-to-S transition. EMBO J. 13:4302-4310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Homesley, L., M. Lei, Y. Kawasaki, S. Sawyer, T. Christensen, and B. K. Tye. 2000. Mcm10 and the MCM2-7 complex interact to initiate DNA synthesis and to release replication factors from origins. Genes Dev. 14:913-926. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ishimi, Y. 1997. A DNA helicase activity is associated with an MCM4, -6, and -7 protein complex. J. Biol. Chem. 272:24508-24513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Izumi, M., K. Yanagi, T. Mizuno, M. Yokoi, Y. Kawasaki, K. Y. Moon, J. Hurwitz, F. Yatagai, and F. Hanaoka. 2000. The human homolog of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Mcm10 interacts with replication factors and dissociates from nuclease-resistant nuclear structures in G(2) phase. Nucleic Acids Res. 28:4769-4777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Izumi, M., F. Yatagai, and F. Hanaoka. 2001. Cell cycle-dependent proteolysis and phosphorylation of human Mcm10. J. Biol. Chem. 276:48526-48531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnson, E. M., Y. Kinoshita, and D. C. Daniel. 2003. A new member of the MCM protein family encoded by the human MCM8 gene, located contrapodal to GCD10 at chromosome band 20p12.3-13. Nucleic Acids Res. 31:2915-2925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kelly, T. J., and G. W. Brown. 2000. Regulation of chromosome replication. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 69:829-880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Labib, K., J. A. Tercero, and J. F. Diffley. 2000. Uninterrupted MCM2-7 function required for DNA replication fork progression. Science 288:1643-1647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee, J. K., and J. Hurwitz. 2001. Processive DNA helicase activity of the minichromosome maintenance proteins 4, 6, and 7 complex requires forked DNA structures. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:54-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li, C.-J., and M. L. DePamphilis. 2002. Mammalian Orc1 protein is selectively released from chromatin and ubiquitinated during the S-to-M transition in the cell division cycle. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22:105-116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liang, C., M. Weinreich, and B. Stillman. 1995. ORC and Cdc6p interact and determine the frequency of initiation of DNA replication in the genome. Cell 81:667-676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Madine, M. A., M. Swietlik, C. Pelizon, P. Romanowski, A. D. Mills, and R. A. Laskey. 2000. The roles of the MCM, ORC, and Cdc6 proteins in determining the replication competence of chromatin in quiescent cells. J. Struct. Biol. 129:198-210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Méndez, J., and B. Stillman. 2000. Chromatin association of human origin recognition complex, Cdc6, and minichromosome maintenance proteins during the cell cycle: assembly of prereplication complexes in late mitosis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:8602-8612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mendez, J., and B. Stillman. 2003. Perpetuating the double helix: molecular machines at eukaryotic DNA replication origins. Bioessays 25:1158-1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mendez, J., X. H. Zou-Yang, S. Y. Kim, M. Hidaka, W. P. Tansey, and B. Stillman. 2002. Human origin recognition complex large subunit is degraded by ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis after initiation of DNA replication. Mol. Cell 9:481-491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Merchant, A. M., Y. Kawasaki, Y. Chen, M. Lei, and B. K. Tye. 1997. A lesion in the DNA replication initiation factor Mcm10 induces pausing of elongation forks through chromosomal replication origins in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17:3261-3271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mizushima, T., N. Takahashi, and B. Stillman. 2000. Cdc6p modulates the structure and DNA binding activity of the origin recognition complex in vitro. Genes Dev. 14:1631-1641. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ohta, S., Y. Tatsumi, M. Fujita, T. Tsurimoto, and C. Obuse. 2003. The ORC1 cycle in human cells: II. Dynamic changes in the human ORC complex during the cell cycle. J. Biol. Chem. 278:41535-41540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Petersen, B. O., C. Wagener, F. Marinoni, E. R. Kramer, M. Melixetian, E. L. Denchi, C. Gieffers, C. Matteucci, J. M. Peters, and K. Helin. 2000. Cell cycle- and cell growth-regulated proteolysis of mammalian CDC6 is dependent on APC-CDH1. Genes Dev. 14:2330-2343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Piatti, S., C. Lengauer, and K. Nasmyth. 1995. Cdc6 is an unstable protein whose de novo synthesis in G1 is important for the onset of S phase and for preventing a ‘reductional’ anaphase in the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO J. 14:3788-3799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Prasanth, S. G., K. V. Prasanth, K. Siddiqui, D. L. Spector, and B. Stillman. 2004. Human Orc2 localizes to centrosomes, centromeres and heterochromatin during chromosome inheritance. EMBO J. 23:2651-2663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ritzi, M., M. Baack, C. Musahl, P. Romanowski, R. A. Laskey, and R. Knippers. 1998. Human minichromosome maintenance proteins and human origin recognition complex 2 protein on chromatin. J. Biol. Chem. 273:24543-24549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sawyer, S. L., I. H. Cheng, W. Chai, and B. K. Tye. 2004. Mcm10 and Cdc45 cooperate in origin activation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Mol. Biol. 340:195-202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sclafani, R. A. 2000. Cdc7p-Dbf4p becomes famous in the cell cycle. J. Cell Sci. 113:2111-2117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sommer, A., K. Bousset, E. Kremmer, M. Austen, and B. Luscher. 1998. Identification and characterization of specific DNA-binding complexes containing members of the Myc/Max/Mad network of transcriptional regulators. J. Biol. Chem. 273:6632-6642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tye, B. K. 1999. MCM proteins in DNA replication. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 68:649-686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Weinreich, M., C. Liang, and B. Stillman. 1999. The Cdc6p nucleotide-binding motif is required for loading mcm proteins onto chromatin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:441-446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wohlschlegel, J. A., S. K. Dhar, T. A. Prokhorova, A. Dutta, and J. C. Walter. 2002. Xenopus Mcm10 binds to origins of DNA replication after Mcm2-7 and stimulates origin binding of Cdc45. Mol. Cell 9:233-240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Young, M. R., and B. K. Tye. 1997. Mcm2 and Mcm3 are constitutive nuclear proteins that exhibit distinct isoforms and bind chromatin during specific cell cycle stages of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Biol. Cell 8:1587-1601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang, Y., Z. Yu, X. Fu, and C. Liang. 2002. Noc3p, a bHLH protein, plays an integral role in the initiation of DNA replication in budding yeast. Cell 109:849-860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zou, L., and B. Stillman. 1998. Formation of a preinitiation complex by S-phase cyclin CDK-dependent loading of Cdc45p onto chromatin. Science 280:593-596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]