Abstract

Given the gap in child psychiatric services available to meet existing pediatric behavioral health needs, children and families are increasingly seeking behavioral health services from their primary care clinicians (PCCs). However, many pediatricians report not feeling adequately trained to meet these needs. As a result, child psychiatric access projects (CPAPs) are being developed around the country to support the integration of care for children. Despite the promise and success of these programs, there are barriers, including the challenge of effective communication between PCCs and child psychiatrists. Consultants from the Maryland CPAP, the Behavioral Health Integration in Pediatric Primary Care (BHIPP) project, have developed a framework called the Five S’s. The Five S’s are Safety, Specific Behaviors, Setting, Scary Things, and Screening/Services. It is a tool that can be used to help PCCs and child psychiatrists communicate and collaborate to formulate pediatric behavioral health cases for consultation or referral requests. Each of these components and its importance to the case consultation are described. Two case studies are presented that illustrate how the Five S’s tool can be used in clinical consultation between PCC and child psychiatrist. We also describe the utility of the tool beyond its use in behavioral health consultation.

Introduction

In any given year, it is estimated that 13–20% of children in the United States have a behavioral health disorder.1,2 Despite increased identification of these concerns in pediatric primary care settings, approximately 75–80% of youth in need of behavioral health services do not receive care.3,4 In part, this is a result of the gap between the need for and availability of child behavioral and mental health services. Currently, there are about 750 children with serious mental illness per child psychiatrist.5

Given the lack of available behavioral health care, families often seek treatment within primary care settings, with a greater proportion of children receiving behavioral health care from their pediatric primary care clinician (PCC) than from behavioral health specialists.6,7 As a result, there has been growing attention to the role of primary care in the children’s mental health system, including the publication of a mental health toolkit by the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), and guidelines and practice parameters for PCCs from the American Academy of Family Practice (AAFP). In national surveys, pediatricians largely endorse that they should be responsible for the identification of mental health concerns among their patients.8 However, pediatricians often report barriers to caring for children with mental health concerns, including inadequate training in treatment of pediatric behavioral health, a lack of confidence in counseling children and adolescents, and limited time in the face of other clinical priorities.9

Given the great proportion of behavioral and mental health care occurring in pediatric primary care settings, child psychiatric access projects (CPAPs) have been developed to support PCCs in caring for children with these concerns. However, effective communication and collaboration between PCCs and behavioral health specialists can present a challenge. This article presents a simple framework that PCCs can use to formulate child behavioral health cases for consultation or referral requests.

Child Psychiatric Access Projects (CPAPs)

CPAPs have been developed in 31 states and the District of Columbia to help address the treatment gap in behavioral health care and to assist in bridging the line of communication between child health PCCs and behavioral health specialists.10 CPAPs engage PCCs in a collaborative relationship with behavioral health specialists in an effort to support the integration of behavioral health into primary care. The mission of these programs is to improve access to care for children with behavioral health needs by building the capacity of PCCs to both provide first-line treatment and to function as gateways to more specialized services. A core feature of the model includes the provision of indirect telephone consultation to PCCs from a child psychiatrist or other behavioral health specialist. In this model, the PCC maintains responsibility for the care of the patient but receives support via telephone consultation—the child psychiatrist or other behavioral health consultant does not see the patient directly or have access to his/her records. The PCCs questions may be clinical in nature, such as requesting guidance regarding assessment, treatment planning, medication management, or may pertain to locating community resources and referrals.10

The Maryland Behavioral Health Integration in Pediatric Primary Care project (MD BHIPP) is a CPAP serving PCCs in Maryland. It is supported by funding from the Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene and operates as a collaboration between the University of Maryland School of Medicine, the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, and Salisbury University. The BHIPP telephone consultation line is open Monday through Friday, 9 AM to 5 PM. Any provider in a primary care setting serving children and youth can call the line, free of charge, regardless of a child’s insurance type or status. Requests for consultation via telephone or e-mail are initially answered by masters’ level behavioral health specialists who gathers clinically relevant information, assists with referrals and can answer general behavioral health questions. A referral and resource telephone consultation is available to assist the PCP in connecting the family to mental health and other services in their community. Specific case questions are triaged to a child psychiatrist or other masters’ level behavioral health clinician, depending on the nature of the call. Consultations triaged to one of these specialists are completed at a time that is convenient for the PCC, usually within 24 h. Within one business day of the consultation, the PCC receives a written consultation summary, including recommendations, for their records. These consultations provide a resource to PCCs who are managing behavioral health issues in their offices. However, due of the nature of telephone consultation there are some barriers to behavioral health consultations, particularly related to communication.

Communication as Barrier

The AAP has identified communication and collaboration between PCCs and behavioral health specialists as one of 10 services central to providing a medical home for children with special health care needs.11 Although central to optimal care delivery, communication between PCCs and specialists is frequently limited or absent.12 The SAMHSA-HRSA Center for Integrated Health Solutions points to the necessity of “regular communication to build relationships and develop a routine process for soliciting questions from the PCC and the consulting psychiatrist.”13 It is recommended that PCCs ask questions about medication use, diagnostic clarifications, co-occurring conditions, and general treatment recommendations.13

New models of integration bring unique challenges for successful communication. Effective communication between the PCC and the specialist is especially critical to the success of a brief telephone consultation. Communication challenges experienced during this process stem from differences in case formulation and diagnostic styles, as well as the varying language and terminology used by the PCC and the specialist.14 PCCs and specialists also have different work and productivity patterns. PCCs often see 4–5 patients an hour and take walk-in appointments for patients with emergent issues.15 Behavioral health specialists typically see patients for significantly longer initial and follow up appointments, allowing for considerably more time to delve into presenting issues of concern but reducing opportunities between patients for taking phone calls or responding to messages.16

In the CPAP model of consultation, the consultant does not generally interact directly with the patient, therefore the PCC is their “eyes and ears” and the full consultation often occurs in fewer than 10–15 min. In addition to the challenge of effectively exchanging complex information in a short period of time, Maryland PCCs have expressed that an initial barrier to using the BHIPP telephone consultation line is that they feel intimidated. They have expressed concerns about having the “right” diagnosis or any diagnosis in hand before calling. And, they are often unsure about what they should have done prior to the call. They are worried about how to present their patient’s clinical information in a useful and efficient way. Overcoming these barriers is critical to the success of child psychiatric telephone consultation.

Tools to Facilitate Communication

Structured or standardized communication tools have been developed as one means to improve both inter-professional communication and provider–patient/caregiver communication. For example, the Situation-Background-Assessment-Recommendation (SBAR) protocol, originally developed by the U.S. Navy as a tool to reduce potentially catastrophic miscommunication, has been used to improve communication between doctors and nurses in acute care settings and has been shown to increase communication and satisfaction.3 It has also been shown to improve efficiency and teamwork in multiple settings, including the emergency room17 and in telephone consultation.18 These tools may be particularly valuable in establishing a “common language” through which people with different training backgrounds can effectively communicate. Given the unique “language” of a psychiatric case formulation,19 we have proposed a tool to bridge the potential communication gap between child psychiatrists acting as consultants and PCCs calling a CPAP consultation line.

The “Five S’s” Framework

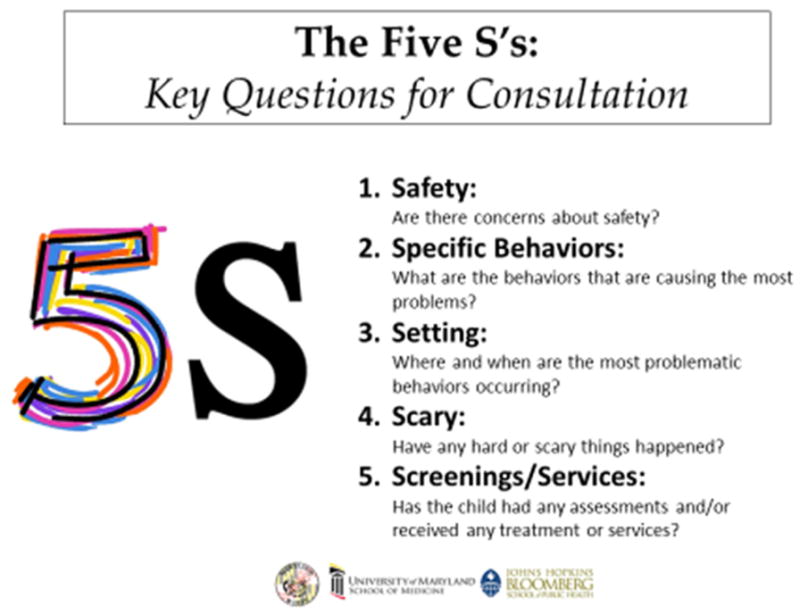

We developed a simple communication tool called “The Five S’s” in an effort to help PCCs prepare for a BHIPP (or other behavioral health) consultation. The information provided by answering five core questions outlined in the Five S’s framework enables the consultant and PCC to exchange the optimal amount of information to formulate a working diagnosis together and develop key next steps in treatment and diagnosis. Consultants have found that asking for simple observations, for example, “What does the child look like in your office?” in addition to eliciting the knowledge PCCs have about the family in the community, are often more useful than asking the PCC to present information in technical terms, which may differ across disciplines. This framework provides PCCs a way to anticipate and organize the patient information needed for the behavioral health consultation. Conversely, the consultants have found the tool useful as a guide in organizing feedback and recommendations to the providers. The “Five S’s” are Safety, Specific Behaviors, Setting, Scary Things, and Screening/Services (Fig).

FIG.

The Five S’s: key questions for consultation.

Safety

Safety is always the primary concern of a child psychiatrist during assessment and treatment. It may not always be obvious upon physical exam that a child is at risk so it is important to routinely inquiring about safety. Safety includes asking about the acuity of the patient’s symptoms as well as suicidal thoughts or intent. While these are difficult topics, they present very real risks for children and adolescents. Suicide is the second leading cause of death for children and adolescents 10–14 years old as well as for adolescents 15–24 years old.20 This information is vital for assessing if the patient can be safely managed in the primary care setting and if the child is at acute risk. Questions to the PCC might include: “Do you have any concerns about the patient’s safety?”; “Do you feel comfortable treating this patient in your practice?”; “Do you think this patient might be suicidal, homicidal, or otherwise at risk?”; and “Are you aware of the patient having any of these safety issues in the past?”

Specific Behaviors

Inquiring about specific behaviors is especially useful in identifying diagnoses and target symptoms for medication intervention and monitoring when appropriate. Questions to the PCC might include “What are the behaviors that are causing the most problems?”; “What is the patient doing that makes you think he has (anxiety, ADHD, depression)?”; and “What are the thoughts or behaviors that are of most concern to the child/youth or family?”

Setting

Ultimately, in order to meet any DSM-5 diagnostic criteria, consideration must be given to where symptomatic behaviors are occurring. Discussions elicited by these questions prove extremely helpful diagnostically, as it can be common for a child or adolescent to display different behaviors in different settings or with different people. For example, if a child is having behavior problems only at school that may be a clue about ADHD or learning disabilities, whereas, a child having behavior problems only at home may suggest family dysfunction, or traumatic exposure. Additionally, there needs to be significant impairment in function across multiple settings before assigning a diagnosis of a psychiatric disorder. Questions to the PCC about setting might include “Where and when are the most problematic behaviors occurring?”; “How is the patient doing academically?”; “How does the patient do with peers?”; and “How is the family managing behavior?”

Scary

Major life changes, stressors, or adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) are frequently the root of behavior problems. Within the mental health field, “trauma” describes a child’s exposure to acute, multiple, or prolonged adverse events and the impact of this exposure on development. Such exposures could involve a range of events such as psychological maltreatment, neglect, physical or sexual abuse, domestic violence, divorce, homelessness, parental substance abuse, or other adverse experiences. These can often be challenging topics for the PCC to address but are common and have significant effects on both short- and long-term mental and physical health. In the landmark ACE study of adults in primary care, it was found that nearly two-thirds reported having experienced one or more ACE.21 High ACE scores have been found to be associated with adolescent pregnancy,22 smoking in adolescents and adulthood,23 obesity in adulthood,24 lifetime depressive disorders,25 and a variety of other poor health outcomes in adolescence and adulthood.

BHIPP consultants have found that questioning PCCs about their patient’s “trauma history” can be a source of miscommunication. Some PCCs have responded to questions about trauma by saying “there haven’t been any broken bones or car accidents or anything like that.” Consultants have found that adjusting their language to ask “Have any hard or scary things happened recently to the family or the patient?” offers a broader way of asking about adverse events and eliminates the differences in the use of the word trauma between the two disciplines. It also allows the PCC to give information about events that have negatively impacted the patient or family.

Screening/Services

One benefit of primary care is the longitudinal nature of the patient’s medical record. PCCs may have access to behavioral health or developmental screening results, behavioral health or education evaluations, or specialty services that the patient may have received in the past or may be currently receiving. These evaluations can be helpful diagnostically, can prevent recommendations that have not worked for this patient or family in the past, and can guide advice on appropriate pharmacologic and therapeutic interventions. Therapists and providers of school-based services often provide information about the patient that is helpful for diagnosis and for monitoring of medication interventions. Questions from the consultant to the PCC may include “Has the patient ever had any screenings or assessments?”; “Has the patient ever had a psychiatric or psychological evaluation?”; “Has the patient ever been psychiatrically hospitalized?”; “Has the patient received therapy or medication in the past?”; “Is the patient currently receiving any medication or therapy?; and “Do you have any communication with the current providers?” PCCs occasionally call about interventions they have already put in place or are considering. To avoid making recommendations that would not be helpful it is important to ask “What have you already tried?”

Case Studies: Application of the “Five S’s” Framework to a Telephone Consultation

The following two cases illustrate the utility of the Five S’s tool in facilitating communication between the PCC and the child psychiatric consultant. The PCC in each case had attended a training which included presentation of the tool and/or case-based discussions.

Case 1

Chief Complaint/Reason for Call

A PCC called about a 3-year 10-month-old female for whom he has significant concerns about hyperactivity and inattention. He feels she has ADHD but “doesn’t want to miss anything.” The provider states that the family was hoping for medication, but he wanted to discuss the case because he felt medication alone would not address the issues. The child has a family history of anxiety in the father and bipolar disorder in a maternal cousin. The PCC also noted that the child has a significant speech delay and he wonders if this communication barrier is exacerbating her problems. There are no motor delays and she is “socially fine.”

Safety

The provider states that the child will get into everything, and was destroying things in his office, and is “all over the place.” She will get “violent” when limits are set.

Specific Behaviors

By parents’ report, she is impulsive, “hyperactive” and inattentive. She can also be oppositional and defiant. The PCC stated that when she was in his office she was “super hyper” to the point where he had difficulty completing his physical exam.

Setting

Parents report having difficulty with the patient at home and daycare is reporting behavioral difficulties as well.

Scary

The provider is not aware of any trauma. He asked parents about physical discipline, and they report that dad has a loud voice, which usually gets things done but mom has no authority.

Screening/Services

The child was evaluated by the local preschool service agency and has considerable language delay. She is receiving speech and behavior services. She had a hearing evaluation that showed normal hearing on the right but some decrease on the left, so the provider plans a repeat audiology assessment. Screening tools were completed by the family and were positive for ADHD, but the second page with information regarding other diagnoses wasn’t completed.

Recommendations Made by Consultant

The consultant made the following recommendations.

In-office intervention

The consultant suggested that this case be referred to the social work intern in their office so that she can work with the parents around behavior management and assist the family in finding a more structured day care/educational setting. The consultant expressed concern that this child may need additional support and further assessment to fully understand the impact of her language difficulties and possible related developmental issues. Specifically, the consultant wondered if the child is receiving adequate early intervention services and thought it would be ideal to get the child enrolled in Head Start, and initiate an Individual Family Service Plan. Screening forms from the childcare setting would help assess the impact of intervention.

Case 2

Chief Complaint/Reason for Call

The PCC called about a 14-year-old female patient. The PCC reported that the main problem right now is regarding school. The patient is failing school, does not want to talk in class, does not want to answer questions, and “hates the teacher” without any cause she can express. The PCC is wondering if she should start this patient on Zoloft to be used in conjunction with continued therapy, whether there are other screens/testing she should be doing, or if something else could be going on. The family imigrated to the US and the parents do not speak English at home. The patient lived in their country of origin until she was 9 or 10 years old and then came to the US with her family. She had lived with her grandmother, away from her parents, until age 9. She continues to spend summers with her grandmother. Father is not in favor of medication—it was mother who called the PCC and asked for medication because the patient is failing a class in school. Father will transport the family to the PCC’s office but declines to attend appointments. The PCC noted that until it has been very difficult to discuss the patient’s mood with the parents because, they say, where they are from “no one is concerned about things like anxiety and depression.” The patient has a younger brother who has developmental delays. The PCC stated that mother told her that the patient was also seen as delayed and spoke very late.

Safety

The PCC stated that from what her patient tells her the father might be considered “emotionally abusive” but that she is not certain how to interpret this in the cultural context.

Specific Behaviors

The PCC asked the patient if she is scared of answering questions or whether she is afraid she will be made fun of to determine what is preventing her from participating in class. She says that she is afraid to say anything at school and hates her teacher. The PCC describes her as shut down, appearing depressed, and as not being well groomed. She does not describe any suicidal thoughts.

Setting

The patient is doing poorly. She is currently failing her government course in school. She has never been a good student. She has no services in school. She has no friends and does not socialize.

Scary

Father is reported as being verbally harsh with the patient and other members of the family. The PCC wonders if the family is stably housed and has sufficient resources for food and clothing, but has not asked about this specifically.

Screening/Services

PCC completed the screen for child-related anxiety disorders (SCARED) which was not indicative of an anxiety disorder and the Pediatric Symptom Checklist (Y-PSC) for which the patient answered often and sometimes to most of the questions. Blood pressure is fine and routine labs are pending. The patient had been seeing a therapist weekly but decreased to bi-weekly because “she had nothing to talk about.” The PCC spoke to the therapist a few months ago and it seemed like things were going well, the patient and the therapist had good rapport and the therapist believed that the patient was responsive to treatment. The PCC spoke to the therapist two weeks ago, however, and the therapist stated that she was concerned about depression and anxiety and thought medication would be helpful. The patient is currently on a four-month wait list for a psychiatrist.

Recommendations Made by Consultant

Additional screening: The consultant thought that given family and patient history of developmental delay, it would be important to assess the patient for learning disabilities, which may also be contributing to her poor school performance. The family could request an IEP/assessment through school. With regard to her social withdrawal and poor hygiene, the question of early psychosis came up. It would be helpful to do the PRIME screen, a self-administered scale designed to identify individuals at risk for developing a psychotic disorder. Screening for basic needs (housing and food security, concerns about safety or discrimination in the family’s neighborhood, worries about immigration issues) as well as for other forms of trauma were also suggested, with linkages to appropriate services depending on what the family disclosed. Learning more about the family’s needs might be a key to establishing a closer therapeutic relationship and perhaps creating openings for additional treatment.

Psychosocial treatment: The consultant wondered if the patient’s therapist was using a particular evidence-based treatment for depression or anxiety—the PCC might ask about this and at the same time initiate a discussion about how that treatment might be intensified or complemented by group therapy, either social skills at school or in the community.

Medication: Assuming that family and patient were willing, a trial of a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) could be considered. Both father’s reluctance and the presence of anxiety symptoms would make it important to effectively manage and interpret any possible side effects. Thus, starting with a low dose and following-up frequently would likely be needed.

The consultant recommended continued screening for trauma both in the patient’s country of origin and in her present living situation. Learning more about the patient’s actual travel to the US, and inquiring tactfully about the family members’ immigration status, might further help understand the patient’s emotional state and family concerns about further engaging with care.

Discussion

These two cases illustrate the utility of the Five S’s framework as a tool to facilitate communication and the process of the PCC and consultant collaborating as they work through a case together. We believe the tool can help overcome some of the barriers to communication between PCCs and child psychiatrists during the consultation process by providing a common language and structure. First, it organizes the discussion using simple but comprehensive questions, potentially limiting the use of technical terminology which can lead to miscommunication. We believe that it has the potential to provide PCCs with greater comfort in calling the telephone consultation line and presenting their cases, as they can anticipate the questions that might be asked and the information that would be most helpful to the consultant. The tool is brief and hones in on only the most critical information, which PCCs can realistically collect in the limited time they have for appointments. And yet, it provides enough depth to allow the consultant to begin the process of formulating a differential diagnosis and make a set of clear and actionable recommendations. Importantly, utilization of the tool does not require the PCC to have formulated a diagnosis, nor have comprehensive information about every component of the tool. For the consultant, it can serve as a reminder to obtain the critical information for formulating the case with the PCC and it can be used to guide their treatment recommendations.

Though this framework was developed within a CPAP model, there may also be applications of the Five S’s framework as a tool for broader usage outside of the formal CPAP model. PCCs practicing in states that do not have CPAP services may, instead, have a behavioral health specialist whom they frequently call for a “curbside consult” or a co-located mental health professional in their office. This framework would work well in formulating the case and communicating the necessary patient data with those individuals. As well, the tool would be helpful to PCCs when they are communicating with behavioral health specialists who are treating their patients in order to enhance the continuity and integration of care for that patient.

Utility Within the Clinical Setting

A primary goal of the CPAP model is that the PCC not only gets a “curbside consult” on the case s/he is calling about but the PCC is also able to increase their general knowledge and comfort around treating children with behavioral and mental health needs. Every consultation is a “teaching moment” and as PCCs gain experience, they may become more efficient and sophisticated during their assessment and in consultation encounters. Repeated use of the Five S’s framework can help PCCs better utilize cases specific consultation, but it may also be used by PCCs in history taking during primary care visits. PCCs may see increased comfort and efficiency in interviews pertaining to behavioral and mental health because they have a familiar framework with key questions about which to ask their patients and family members when concerns arise.

Utility in Education

Beyond the individual patient-provider encounter, we believe that the Five S’s tool could be used with PCCs in pediatric residency or other training programs such as family practice and developmental pediatrics as they learn how to assess and manage children with behavioral and mental health disorders and how to communicate with consultants outside of their specialty. Both trainees and program directors acknowledge insufficient mental health training during residency, with many trainees expressing a lack of comfort managing child mental health problems.26,27 In this setting the Five S’s tool may be helpful for increasing facility with addressing such problems. The infographics in the Figure can be used as a prompt until PCCs or trainees become comfortable using the tool.

Potential Limitations

While the framework has a variety of applications, there may also be barriers to its utilization. For PCCs who are time-pressured, while it is a brief tool, there may still be limitations in their time to first gather the data (from the patient or family directly or from the medical record), and then organize the data, all before calling the line. However, if the PCC does not have this time to invest, simply being aware of categories for further information gathering can be helpful, and the consultant can provide assistance and guidance for specific questions to ask the child/youth or family. Further, an initial investment of time may save time in the long run if it allows for either more efficient consultation or more efficient history taking. For example, implementation of the Situation-Background-Assessment-Recommendation (SBAR) protocol led to more timely inclusion of essential information for handoffs in a pediatric critical care setting.28 If implemented systematically within an office or practice, it may be possible to have additional staff pull data from the chart prior to the consultation in order to save time.

Another potential barrier is that in the era of the electronic medical record (EMR), with its multitude of templates and checklists, prompts that are not embedded directly into the EMR may be difficult to utilize systematically. It may be difficult for providers to remember to ask and record answers to these questions “outside” of the standard template. As EMR practices may affect both case formulation and the practice of case presentation,29 it may be more difficult to learn to re-formulate cases in a different manner for use in a limited number of cases or consultation calls.

Conclusion

Despite these potential barriers, the Five S’s framework is a simple and brief communication tool with a number of strengths. It allows for clear and efficient communication and collaboration between PCCs and child psychiatrists or other behavioral health specialists. It can be helpful for trainees, new PCCs, and more experienced PCCs, from a variety of disciplines, who need to expand their training, knowledge, and skills in assessing and treating children with a variety of behavioral and mental health needs. Given the gap in treatment options for children, equipping PCCs to provide behavioral health screening and treatment will allow more children to have their behavioral health needs met.

Acknowledgments

The BHIPP project is supported by the Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, United States, under Grant no. 16-14685G. Maryland BHIPP is a collaboration among University of Maryland School of Medicine, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, and Salisbury University. We are grateful to David Pruitt, MD, and Larry Wissow, MD, program co-directors, for their review and comment on the manuscript.

References

- 1.Merikangas Kathleen Ries, et al. Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in us adolescents: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication-Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A) J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;49(10):980–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Connell ME, et al. National Research Council (US) and Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on the Prevention of Mental Disorders and Substance Abuse among Children, Youth, and Young Adults. Research Advances and Promising Interventions. 2014;71:81–90. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vardman JM, et al. U.S. Public Health Service, Department of Health and Human Services. 2012;37:88–97. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sheryl Kataoka H, Zhang Lily, Wells Kenneth B. Unmet need for mental health care among U.S. children: variation by ethnicity and insurance status. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(9):1548–1555. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.9.1548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim Wun Jung American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Task Force on Workforce Needs. Child and adolescent psychiatry workforce: a critical shortage and national challenge. Acad Psychiatry. 2003;27(4):277–82. doi: 10.1176/appi.ap.27.4.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elizabeth Anderson L, et al. Outpatient visits and medication prescribing for US children with mental health conditions. Pediatrics. 2015;136(5):e1178–85. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-0807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Olfson Mark, et al. National trends in the mental health care of children, adolescents, and adults by office-based physicians. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(1):81–90. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.3074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stein Ruth EK, et al. Do pediatricians think they are responsible for identification and management of child mental health problems? Results of the AAP Periodic Survey. Ambul Pediatr. 2008;8(1):11–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ambp.2007.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Horwitz SM, et al. Barriers to the identification and management of psychosocial issues in children and maternal depression. Pediatrics. 2007;119(1):e208–18. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Straus John H, Sarvet Barry. Behavioral health care for children: the Massachusetts Child Psychiatry Access Project. Health Aff. 2014;33(12):2153–61. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.American Academy of Pediatrics, Medical Home Initiatives for Children with Special Health Care Needs Project Advisory Committee. The medical home. Pediatrics. 2002;110(1 Pt 1):184–6. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gandhi TK, et al. Communication breakdown in the outpatient referral process. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15(9):626–31. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.91119.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.SAMHSA-HRSA Center for Integrated Health Solutions. A Quick Start Guide to Behavioral Health Integration for Safety-Net Primary Care Providers. https://www.thinglink.com/channel/622854013355819009/slideshow02/12/2016.

- 14.Atwal Anita, Caldwell Kay. Do multidisciplinary integrated care pathways improve interprofessional collaboration? Scand J Caring Sci. 2002;16(4):360–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-6712.2002.00101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schyve Paul M. Language differences as a barrier to quality and safety in health care: the joint commission perspective. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(suppl 2):360–1. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0365-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.O’Malley Ann S, Reschovsky James D. Referral and consultation communication between primary care and specialist physicians: finding common ground. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(1):56–65. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martin Heather A, Ciurzynski Susan M. Situation, background, assessment, and recommendation-guided huddles improve communication and teamwork in the emergency department. J Emerg Nurs. 2015;41(6):484–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jen.2015.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Joffe Erel, et al. Evaluation of a problem-specific SBAR tool to improve after-hours nurse-physician phone communication: a randomized trial. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2013;39(11):495–501. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(13)39065-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bolton Jonathan W. How to integrate biological, psychological, and sociological knowledge in psychiatric education: a case formulation seminar series. Acad Psychiatry. 2015;39(6):699–702. doi: 10.1007/s40596-014-0223-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 10 Leading Causes of Death, United States, All Races, Both Sexes. 2014 http://webappa.cdc.gov/sasweb/ncipc/leadcaus10_us.html.

- 21.Felitti VJ, et al. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. Am J Prev Med. 1998;14(4):245–58. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(98)00017-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hillis Susan D, et al. The association between adverse childhood experiences and adolescent pregnancy, long-term psychosocial consequences, and fetal death. Pediatrics. 2004;113(2):320–327. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.2.320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Anda RF, et al. Adverse childhood experiences and smoking during adolescence and adulthood. J AmMed Assoc. 1999;282(17):1652–1658. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.17.1652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Williamson DF, et al. Body weight and obesity in adults and self-reported abuse in childhood. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2002;26(8):1075–82. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chapman Daniel P, et al. Adverse childhood experiences and the risk of depressive disorders in adulthood. J Affect Disord. 2004;82(2):217–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2003.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Green Cori, et al. The current and ideal state of mental health training: pediatric program director perspectives. Acad Pediatr. 2014;14(5):526–32. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2014.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hampton Elisa, et al. The current and ideal state of mental health training: pediatric resident perspectives. Teach Learn Med. 2015;27(2):147–54. doi: 10.1080/10401334.2015.1011653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McCrory Michael Conor, et al. “ABC-SBAR” training improves simulated critical patient hand-off by pediatric interns. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2012;28(6):538–43. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0b013e3182587f6e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tierney MJ, et al. Medical education in the electronic medical record (EMR) era: benefits, challenges, and future directions. Acad Med. 2013;88(6):748–52. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182905ceb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]