Abstract

Exposure to cigarette coupons is associated with smoking initiation and likelihood of cigarette purchase among adolescents. Some adolescents who are exposed to cigarette coupons take a step further by choosing to save or collect these coupons, a further risk factor for cigarette smoking. This study examines historical trends and disparities in cigarette coupon saving among adolescents in the United States from 1997–2013. National samples of 10th and 12th grade students (n=129,111) were obtained from Monitoring the Future surveys in 1997–2013. Prevalence of lifetime and current cigarette coupon saving was estimated in each year in the overall adolescent population, and in race/ethnicity, parent education level, sex, and urban/rural subgroups. Prevalence of lifetime and current cigarette coupon saving was then estimated in each year based on smoking status. Prevalence of cigarette coupon saving has decreased dramatically among adolescents; only 1.2% reported currently saving coupons in 2013. However, disparities in cigarette coupon saving remain with prevalence higher among rural, White, and low parental education level students. Adolescent smokers continue to save coupons at high rates; 21.2% had ever saved coupons and 6.9% currently saved coupons as of 2013. Despite overall declines in adolescent cigarette coupon saving, existing sociodemographic disparities and the considerably high prevalence of coupon saving among adolescent smokers suggest that cigarette coupons remain a threat to smoking prevention among youth. Additional research is needed to further elucidate longitudinal associations between cigarette coupon saving and smoking initiation and maintenance among adolescents.

Keywords: Cigarette coupons, tobacco marketing, adolescents, adolescent smoking, smoking disparities, smoking prevention, tobacco control policy

INTRODUCTION

Federal, state, and local tobacco control policies have contributed to the decline in smoking prevalence among US adolescents in part through efforts to limit tobacco marketing.1–5 Although adolescent smoking prevalence declined from 36.4% in 1997 to 15.7% in 2013,6 sociodemographic disparities remain. In 2015, prevalence of cigarette smoking was higher among White (versus Black and Hispanic, 12.4% vs 9.2% and 6.5%, respectively)7 and rural (versus urban, 9.2% vs 3.4%) adolescents.8 Smoking prevalence was also higher among low (versus high) socioeconomic status high school students (9.3% vs 3.3% among 10th grade students, and 12.9% vs 7.5% among 12th grade students).9 Continuous investigative monitoring and evaluation of policies is needed to identify loopholes in existing adolescent smoking prevention efforts. One such loophole is the continued exposure of adolescents to tobacco industry marketing via cigarette coupons, which have been shown to increase adolescents’ susceptibility to smoking.10–12

Cigarette coupon distribution is a common marketing strategy employed by the tobacco industry to promote sales.13, 14 Although major federal legislation has restricted tobacco marketing to youth, there is little federal regulation on cigarette coupon distribution specifically.15, 16 Most states now have laws that prohibit the distribution of cigarette coupons to adolescents,16, 17 yet opportunities to access coupons remain. Evidence suggests that adolescents are still exposed to cigarette coupons through mailings, online sources, cigarette packages, and social sources.10–12, 18 Recent work found that 86.5% of direct tobacco company mailings to consumers contained at least one coupon.19 Although adolescents may not be the intended recipients of these mailings, 6% of adolescents aged 15–17 years reported exposure to direct tobacco mails in a 2011 national telephone study.11 Similarly, a 2012 study using National Youth Tobacco Survey (NYTS) found that 13.1% of middle and high school students were exposed to cigarette coupons, with 6% reporting exposure through the mail.10 Adolescents also reported exposure to cigarette coupons through digital communications including email, text messages, and social networking sites such as Facebook and Twitter.10 Also using the NYTS, a 2011 study reported that 11% of adolescents were exposed to tobacco advertisements and promotions, including coupons, through social networking sites, and 4% via text messages.12 Thus, adolescents continue to have access to cigarette coupons through a variety of channels.

Cigarette coupons primarily take two forms: price discounts and loyalty programs. Price discount coupons reduce the effect of price increases caused by taxation of tobacco products.13, 14 Proof-of-purchase redemption programs, such as Camel Cash and Marlboro Miles, were attached to cigarette packages and used to promote brand loyalty.20–22 These loyalty programs offered point accumulation in exchange for catalogued, and often tobacco branded merchandise.21, 22 Camel Cash and Marlboro miles were discontinued in 2006 and 2007, respectively, but price discount coupons remain.

The majority of studies on adolescents and cigarette coupons have focused on exposure to coupons, which is generally defined as receiving a coupon from a tobacco company through any of a variety of channels (e.g. direct mail, online, text messages).10–12, 18 Exposure to cigarette coupons has been shown to be associated with increased susceptibility to cigarette smoking among adolescents.10–12 Also, adolescent smokers who are exposed to cigarette coupons have an increased likelihood to purchase cigarettes in the next 30 days.18 Receipt of coupons in the mail is associated with decreased quit attempts, and unsuccessful quitting among young adult smokers.23

Some youth who are exposed to cigarette coupons take a step further by choosing to save or collect these coupons.20, 21 Adolescent current smokers are more likely than experimental or never smokers to report exposure to cigarette coupons and to collect cigarette coupons.10, 11, 20 Cigarette coupon saving may be indicative of susceptibility to cigarette smoking among nonsmokers. Among smokers, saving cigarette coupons may be an attempt to offset price increases in cigarettes. Therefore, the desired decline in cigarette consumption—by increasing cigarette prices—may not be achieved among adolescent smokers who have access to cigarette coupons.

Despite the fact that most smoking onset occurs during adolescence and exposure to tobacco marketing increases adolescents’ susceptibility to smoking,5, 24 studies examining exposure to cigarette coupons in the U.S. have largely focused on adult smokers.23, 25–28 The few studies of adolescents have primarily examined the association between exposure to coupons and smoking behavior in a single wave of data, showing that prevalence of exposure to coupon saving is highest among smokers compared with non-smokers, and adolescents exposed to coupons have elevated susceptibility to smoking.10–12 Sociodemographic disparities in exposure to coupons among adolescents are yet to be thoroughly examined. Previous studies found no sex differences in adolescent exposure to tobacco coupons, but reported racial disparities in channels of exposure.10–12 Whites were found to be more likely than Blacks (6.6% vs 4.6%) to be exposed to tobacco coupons through the mail, and Hispanics were more likely than Whites to report exposure through digital communication (9.2% vs 6.3%).10 These previous studies were all conducted using just one year of data, and disparities in adolescent coupon exposure based on socioeconomic status (SES) and urbanicity were not investigated. Historical trends in adolescents’ exposure to cigarette coupons, variation in coupon saving among demographic subgroups known to differ in their tobacco use, and historical trends in coupon saving among adolescent smokers compared to nonsmokers are yet to be examined. It is important to document historical trends in order to understand the effects over time of existing policies and programs and the gaps still remaining. Further, it is important to document disparities in order to identify groups of young people who are most involved in coupon saving and potentially most vulnerable to smoking.

The current study aims to (1) examine historical trends in cigarette coupon saving by US adolescents, (2) identify disparities among sociodemographic groups in coupon saving, and (3) examine the historical trends in cigarette coupon saving among adolescents based on their smoking status. We hypothesize the overall prevalence of cigarette coupon saving has decreased historically, but significant sociodemographic disparities exist. Also, the prevalence of cigarette coupon saving will remain high among adolescent cigarette smokers.

METHODS

National samples of 10th and 12th grade students (n=129,111) from 1997–2013 were obtained from the Monitoring the Future (MTF) Study and analyzed in 2016. MTF is an ongoing, national survey focused on adolescent substance use.29 The sample is representative of 10th and 12th grade students in the United States. Data were accessed via the Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research (www.icpsr.umich.edu). This studied was determined to be exempt from IRB oversight by University of Texas Institutional Review Board because we analyzed de-identified secondary data. 51.4% of participants were female; 75.7% were White, 15.1% Black, and 9.1% Hispanic. 20.5% resided in a rural area (outside of a metropolitan statistical area). Participants’ self-reported father and mother education level, respectively, were 14.6% and 11.9% less than high school, 29.1% and 26.7% high school, 16.5% and 19.8% some college, and 39.7% and 41.6% college or higher.

Cigarette coupon saving was measured via two items. Lifetime coupon saving was measured via the item “Have you ever saved coupons from cigarettes (whether or not you bought them yourself)?” Current coupon saving was measured via the item “Are you currently saving coupons from cigarettes?” Responses to each item were dichotomous (Yes/No). Participants were labeled “ever coupon savers” if they responded yes to the first item, regardless of current coupon saving behavior. Participants were labeled “current coupon savers” if they responded yes to the second item. All “current coupon savers” were also included in the “ever coupon savers” group.

Cigarette smoking in the past 30 days was measured via one item: “How frequently have you smoked cigarettes during the past 30 days?” Response was on a 7-point scale ranging from “not at all” to “two packs or more per day.” For purposes of the current study, those who reported they had smoked cigarettes “not at all” were coded as non-smokers. Those who reported smoking at least one puff or anything more in the past 30 days were coded as smokers.

Sociodemographic variables were race/ethnicity, sex, age, parental education (an indicator of socioeconomic status), and urbanicity. Race/ethnicity categories were limited to Black and White prior to 2005 and to White, Black, and Hispanic from 2005 onward. Urbanicity was based on students’ school location and classified as either metropolitan statistical area (MSA or urban) (≥50,000 population) or non-metropolitan statistical area (non-MSA or rural) (<50,000 population). Parental education was measured as the average of highest level of education achieved by each parent (or the highest education achieved by one parent in the case of single-parent families) ranging from “completing grade school or less” to “graduate or professional school after college.” Parental education level was stratified into four quartiles, with the first quartile representing lowest educational level (low SES) and the fourth quartile representing highest educational level (high SES).

Statistical Analyses

Data on 10th and 12th grade students were combined and the percentage of students who reported ever and currently saving coupons was estimated for each year. The percentage of students who had ever saved coupons was estimated across subgroups by race/ethnicity, sex, urbanicity, and SES (1st vs. 4th parental educational level quartiles). We used independent sample t-tests to test differences in tobacco coupon saving between subgroups. Estimation of sociodemographic differences was limited to adolescents who had ever saved coupons because of the relatively small sample sizes of those currently saving coupons. The prevalence of lifetime and current cigarette coupon saving were estimated for adolescent smokers and nonsmokers for each year. Finally, because 12th grade students may have turned 18 years old and therefore be eligible to purchase tobacco products and redeem cigarette coupons legally, a supplementary analysis was conducted to test whether coupon saving varied according to whether the student was under 18 years or 18 years and older. All analyses were performed using SPSS version 23. Sampling weights were applied in all analyses to account for design-based oversampling of some groups.29

RESULTS

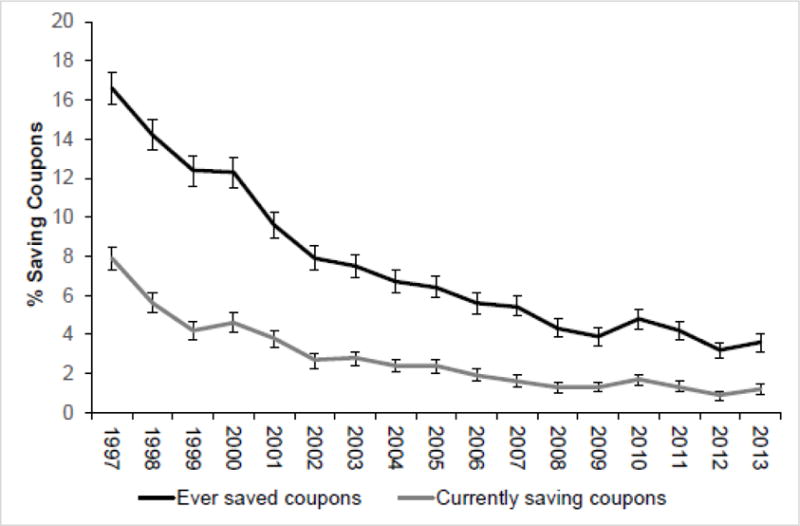

The prevalence of lifetime and current cigarette coupon saving among adolescents decreased from 1997–2013 (Figure 1). Prevalence of lifetime coupon saving declined from 16.6% in 1997 to 3.6% in 2013. The percentage of students currently saving coupons declined from 7.9% in 1997 to 1.2% in 2013.

Figure 1.

Trends in cigarette coupon saving from 1997–2013. Error bars represent 95% Confidence Interval (CI).

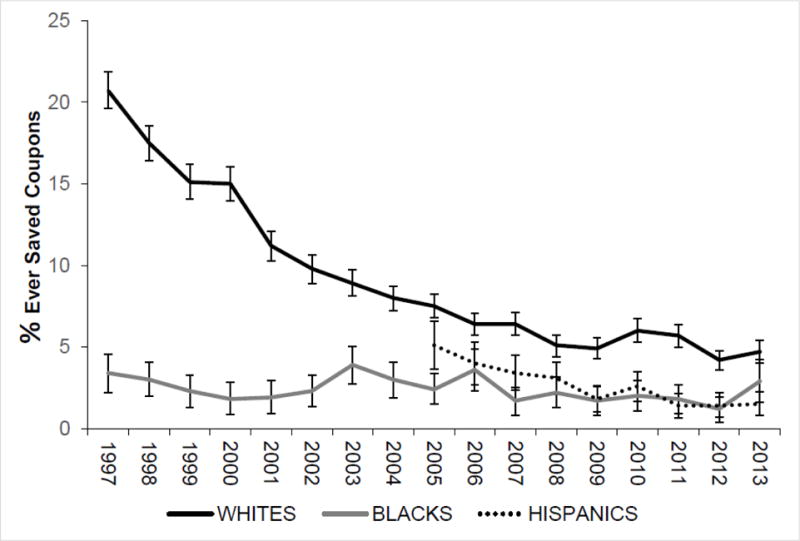

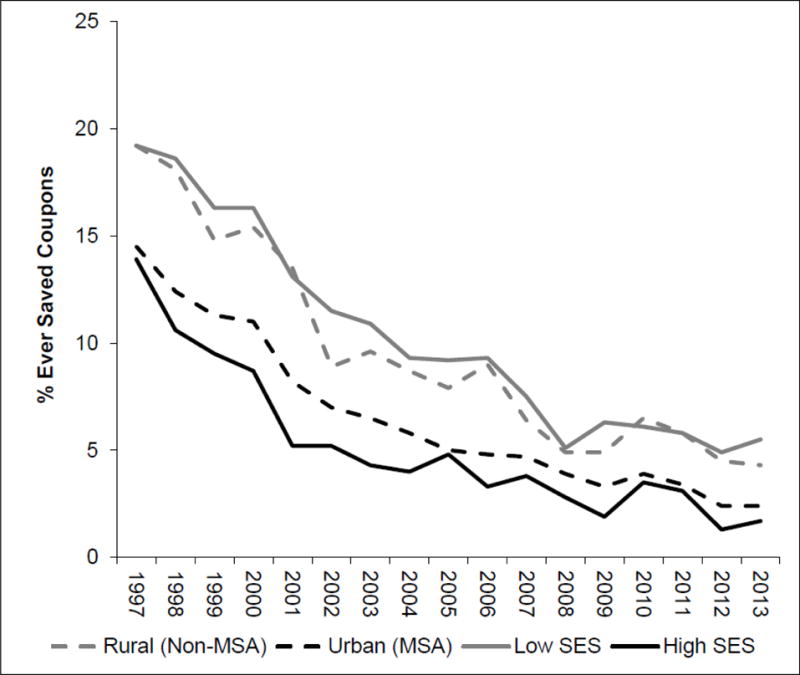

There were significant sociodemographic disparities in prevalence of lifetime coupon saving. Figure 2 depicts racial differences. From 1997–2012, Whites had a significantly higher prevalence of ever saving coupons than Blacks. However, while prevalence of ever coupon saving significantly declined among Whites (20.7% in 1997 vs 4.7% in 2013), it remained relatively stable among Black students (3.4% in 1997 vs 2.9% in 2013), such that by 2013, the difference between Whites and Blacks was only marginally significant. Whites had a significantly higher prevalence of ever saving coupons than Hispanics in all years in which Hispanics were categorized separately (2005–2013). Figure 3 depicts differences by urbanicity and parental education. From 1997–2013, the percentage of students who reported ever saving coupons was consistently higher among rural compared to urban students. In 1997, 19.2% of rural versus 14.5% of urban adolescents reported ever saving coupons. By 2013, the percentage of adolescents who had ever saved coupons had declined to 4.3% and 2.4% among rural and urban students, respectively. Also, Figure 3, low SES students had consistently higher prevalence of ever coupon saving than students of high SES. Prevalence of ever coupon saving was 19.2% and 13.9% in 1997 among low and high SES students, and declined to 5.5% and 1.7% respectively, in 2013. There were no significant sex differences in prevalence of ever coupon saving. Notably, in supplementary analyses (not tabled) among 12th grade students, the percentage of adolescents who had ever saved coupons was similar regardless of whether students were <18 years or ≥18 years of age. Error bars in all figures denote 95% confidence intervals and demonstrate that the observed sociodemographic disparities in coupon saving were significant in most years.

Figure 2.

Disparities in cigarette coupon saving by race/ethnicity (White, Black, Hispanic). Error bars represent 95% CI.

Figure 3.

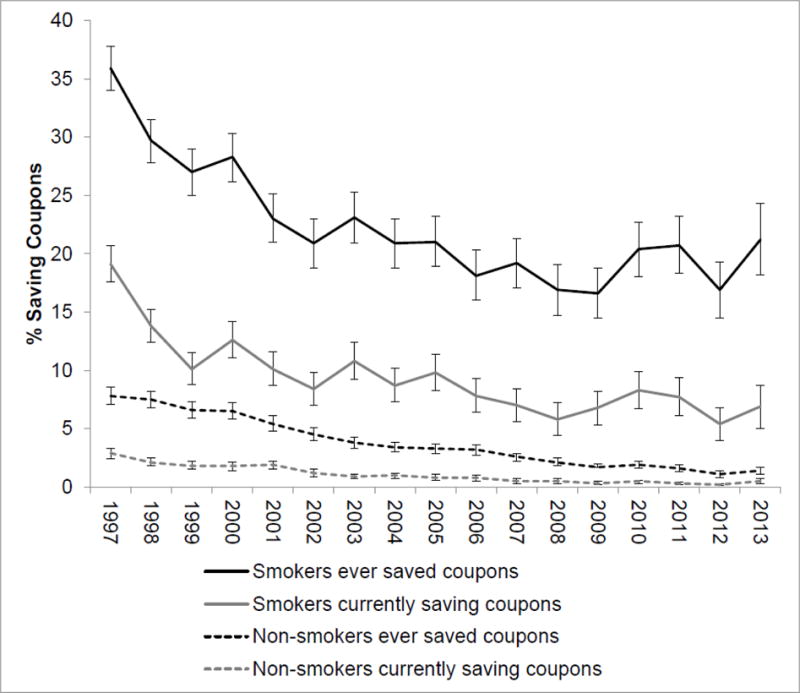

Regarding differences in coupon saving by smoking status, prevalence of lifetime coupon saving declined from 35.9% in 1997 to 21.2% in 2013 among adolescent smokers, and from 7.8% in 1997 to 1.4% in 2013 among nonsmokers. Also, prevalence of current coupon saving declined from 19.1% in 1997 to 6.9% in 2013 among adolescent smokers, and 2.9% in 1997 to 0.5% in 2013 among nonsmokers (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

DISCUSSION

This study is the first to examine historical trends in cigarette coupon saving in a national adolescent sample. At first glance, the decline in prevalence of cigarette coupon saving among adolescents appears to be a public health success. However, significant sociodemographic disparities in coupon saving, and considerably high rates of cigarette coupon saving among adolescent smokers suggest that coupon saving remains a threat to tobacco control among US adolescents.

There are significant sociodemographic disparities in cigarette coupon saving, with prevalence higher among White, rural, and low SES youth. We observed statistically significant racial differences throughout the study period. The magnitude of these differences between Whites and Blacks ranged from a large 17.3% difference in 1995 to small but marginally significant difference of 1.8% by 2013. Between Whites and Hispanics, the differences in prevalence were statistically significant throughout the study period but were of small magnitude (2.4% in 2005 and 3.2% in 2013). Given the small magnitude of the racial differences in prevalence, the practical significance of these differences may be limited. Of more likely practical significance is the fact that tobacco coupon saving among Blacks has remained relatively stable, albeit low, over the past two decades, while coupon saving has fallen among Hispanics and Whites. A topic for future research would be to consider why we have not observed a similar decline among Blacks and whether current efforts are not functioning well in this population.

Our results extend those of prior studies, which demonstrated racial disparities in coupon exposure in the 2011 and 2012 National Youth Tobacco Surveys,10–12 by establishing the long-term historical presence and persistence of these disparities. However, contrary to these previous studies, our findings reveal long-term disparities in coupon saving between Whites and Blacks that closed in 2013, and persistently high prevalence of coupon saving among Whites compared to Hispanics. Our findings also mirror the sociodemographic disparities in adolescent smoking among low SES and rural populations.8, 9 Low SES and rural adolescents are vulnerable populations, as they already experience a number of health disparities, such as reduced access to health care and preventive health care services.30–32 Engaging in coupon saving, which may put them at high risk of smoking initiation and maintenance, may lead to an exaggeration of existing health disparities.

The prevalence of cigarette coupon saving declined steeply through the 1990s but remains fairly constant beyond the early 2000s. Our results, which focused on cigarette coupon saving, are consistent with a previous study that focused on use of cigarette coupons and documented a decline (from 18% in 2005 to 8.2% in 2011) in the reported use of cigarette coupons and special discounts among adult smokers33 Our study extends the literature documenting historical trends in coupon saving among smokers, previously limited to adults, to an adolescent population. Our study also showed that despite the decline, prevalence of coupon saving remains considerably high among adolescent cigarette smokers. Our most recent estimates of prevalence of cigarette coupon saving among adolescent smokers show that 21.2% had ever saved and 6.9% currently saved coupons in 2013. These estimates likely represent only a fraction of all adolescent smokers exposed to cigarette coupons, because exposure to coupons may not necessarily lead to coupon saving. However, simple exposure to cigarette coupons, regardless of whether they are saved or even used has been shown to increase likelihood of cigarette purchase among adolescent smokers.18 Further, adolescent current smokers are more likely than experimental or never smokers to report exposure to cigarette coupons and to collect cigarette coupons.10, 11, 20 Our findings demonstrate that although prevalence of cigarette coupon saving has declined over the years, a significant percentage of adolescent smokers still engage in cigarette couponing despite the presence of regulatory measures.

There are several possible explanations for the decline in cigarette coupon saving from 1997–2013. One reason may be the decline in adolescent smoking prevalence over the past two decades, which is attributable to a constellation of federal, state, and local policies.1–5 Lower smoking prevalence may decrease demand for coupons; one does not need a coupon for a product one does not buy. It may also reduce the supply of coupons, as one major method of coupon distribution is cigarette packages. Another possible explanation for this decline could be the discontinuation of once popular loyalty programs such as Marlboro Miles and Camel Cash, in 2006 and 2007, respectively. Tobacco regulatory measures also increasingly restrict tobacco marketing and prohibit tobacco coupon distribution to adolescents in most states.16 The tobacco industry’s coupon-specific expenditures (a conservative estimate of all price-discount related expenditures) for cigarettes declined from about $553 million (9.8% of total industry marketing expenditures) in 1998 to about $240 million (2.6%) in 2012, which may also have contributed to the decline we observed in coupon saving.34

Although minors are legally prohibited from redeeming cigarette coupons, it is plausible that some youth who save coupons find means of redeeming them. We found that adolescents under age 18 saved coupons at comparable rates to those over age 18. Although all states in the U.S have laws that prohibit cigarette purchases by individuals under age 18,35 results from 2013 Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance (YRBS) showed that 18.1% of adolescent smokers under age 18 reported purchasing cigarettes from stores and gas stations,6 where age verification is technically required but not always enforced. There may also be opportunities to purchase cigarettes (and redeem coupons) with the help of family, older friends, and relatives.36, 37 Where there are opportunities to purchase cigarettes without age verification, there may also be opportunities for youth to redeem cigarette coupons despite age-related prohibitions.

Our results suggest a need for stronger enforcement of existing policies regarding cigarette coupon availability to minors and/or enactment of new coupon-specific policies. With research revealing avenues through which adolescents (under 18 years of age) obtain cigarettes,6 and plausibly redeem coupons, more needs to be done to restrict coupon redemption. A viable option might be a complete ban on cigarette coupons, as implemented in the United Kingdom in 2003.38 Existing policies in New York City and Providence, Rhode Island that prohibit cigarette coupon redemption are strong alternatives that can be enacted and implemented by other states and localities.17

Study Limitations

This study has several limitations. Cigarette coupon saving was measured via single item, self-reported measures that ask whether the adolescent has ever saved or currently saves coupons from cigarettes. The items do not address how he or she obtained the coupons or whether he or she has redeemed them. However, previous research has shown that exposure to coupons may increase susceptibility to smoking and likelihood to purchase cigarettes, regardless of redemption.18 Our measures are comparable to those employed in existing studies of coupon saving,20, 21 and we extend upon that previous research with 17 years of data in a national sample. Second, Hispanic individuals were not separately categorized in data collected prior to 2005,29 therefore they could not be distinguished as a separate group in prevalence estimates of cigarette coupon saving and cigarette smoking. Finally, the current cross-sectional data cannot demonstrate a causal relationship between cigarette coupon saving and cigarette smoking. Additional, longitudinal studies are warranted to investigate whether cigarette coupon saving is independently and prospectively associated with onset of cigarette smoking among adolescents.

CONCLUSIONS

The current study demonstrates that prevalence of cigarette coupon saving among U.S. adolescents has declined substantially from 1997–2013. While reducing cigarette coupon saving among the general adolescent population may be considered a public health success, there is still work to be done. Sociodemographic disparities in adolescent coupon saving are decreasing, however, prevalence remains high among adolescent smokers, and relatively higher in white (versus Hispanic), rural (versus urban), and low-SES adolescents. Cigarette coupon saving remains a problem among adolescent smokers. Adolescent smokers who save cigarette coupons may be a small but practically significant population yet to be successfully impacted by existing tobacco control policies. Though tremendous progress has been made in reducing adolescent smoking in the US, new obstacles continue to emerge and threaten to erode the achieved success, particularly the introduction of new tobacco products and methods of promoting their purchase. The current results and additional future research on the regulatory strategies underlying the significant decline in cigarette coupon saving may be applicable in future efforts to address marketing and coupon distribution for new tobacco products such as electronic cigarettes.39

HIGHLIGHTS.

Sociodemographic disparities exist in cigarette coupon saving among US adolescents.

High prevalence of cigarette coupon saving among US adolescent smokers.

Cigarette coupons remain a threat to smoking prevention among US adolescents.

Adolescents’ means of accessing and redeeming coupons should be further investigated.

Research on the most effective policy interventions is warranted.

Acknowledgments

FUNDING

This research was supported by grant R24HD042849, Population Research Center, awarded to the Population Research Center at The University of Texas at Austin by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

Contributor Information

Olusegun Owotomo, Department of Kinesiology & Health Education, University of Texas at Austin, Texas, USA.

Julie Maslowsky, Department of Kinesiology & Health Education, Population Research Center, University of Texas at Austin, Texas, USA.

Keryn E. Pasch, Department of Kinesiology & Health Education, University of Texas at Austin, Texas, USA.

References

- 1.Pierce JP, White VM, Emery SL. What public health strategies are needed to reduce smoking initiation? Tob Control. 2012;21(2):258–264. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hawkins SS, Bach N, Baum CF. Impact of tobacco control policies on adolescent smoking. J Adolesc Health. 2016;58(6):679–685. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.02.014. doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Farrelly MC, Loomis BR, Han B, et al. A comprehensive examination of the influence of state tobacco control programs and policies on youth smoking. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(3):549–555. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jones WJ, Silvestri GA. The Master Settlement Agreement and its impact on tobacco use 10 years later: lessons for physicians about health policy making. Chest. 2010;137(3):692–700. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-0982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Preventing tobacco use among youth and young adults: a report of the surgeon general. 2012 http://www.surgeongeneral.gov/library/reports/preventing-youth-tobacco-use/full-report.pdf; Accessed August 30, 2016. [PubMed]

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Youth risk behavior surveillance-United States, 2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63(SS04):1–168. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kann L, McManus T, Harris WA, et al. Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance — United States, 2015. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2016;65(SS-6):1–174. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.ss6506a1. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.ss6506a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2015 national survey on drug use and health: detailed tables. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-DetTabs-2015/NSDUH-DetTabs-2015/NSDUH-DetTabs-2015.pdf. Accessed February 14, 2017. [PubMed]

- 9.Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Miech RA, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Demographic subgroup trends among adolescents in the use of various licit and illicit drugs, 1975–2015 (Monitoring the Future Occasional Paper No 86) http://monitoringthefuture.org/pubs/occpapers/mtf-occ86.pdf. Accessed February 14, 2017.

- 10.Tessman GK, Caraballo RS, Corey CG, et al. Exposure to tobacco coupons among U.S. middle and high school students. Am J Prev Med. 2014;47(2 Suppl 1):S61–68. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Soneji S, Ambrose BK, Lee W, et al. Direct-to-consumer tobacco marketing and its association with tobacco use among adolescents and young adults. J Adolesc Health. 2014;55(2):209–215. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.01.019. doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cavazos-Regh PA, Krauss MJ, Spitznagel EL. Hazards of new media: youth’s exposure to tobacco ads/promotions. Nicotine Tob Res. 2014;16(4):437–444. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntt168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chaloupka FJ, Cummings KM, Morley CP, et al. Tax, price and cigarette smoking: evidence from the tobacco documents and implications for tobacco company marketing strategies. Tob Control. 2002;11(Suppl 1):i62–72. doi: 10.1136/tc.11.suppl_1.i62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Choi K, Hennrikus D, Forster J, et al. Use of price-minimizing strategies by smokers and their effects on subsequent smoking behaviors. Nicotine Tob Res. 2012;14(7):864–870. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntr300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Association of Attorneys General. Master Settlement Agreement. 1998 http://www.naag.org/naag/about_naag/naag-center-for-tobacco-and-public-health/master-settlement-agreement/master-settlement-agreement-msa.php; Accesses August 30, 2016.

- 16.Tobacco Control Legal Consortium. Policy approaches to restricting tobacco product coupons and retail value-added promotions. 2013 http://publichealthlawcenter.org/sites/default/files/resources/tclc-guide-policy-approaches-pricing-cppw-2013.pdf; Accessed August 30, 2016.

- 17.Tobacco Control Legal Consortium. Death on a discount: regulating tobacco product pricing. 2015 http://publichealthlawcenter.org/sites/default/files/resources/tclc-fs-death-on-discount-2015.pdf; Accessed August 30, 2016.

- 18.Choi K. The associations between exposure to tobacco coupons and predictors of smoking behaviours among US youth. Tob Control. 2016;25(2):232–235. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-052147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brock B, Schillo BA, Moilanen M. Tobacco industry marketing: an analysis of direct mail coupons and giveaways. Tob Control. 2015;24(5):505–508. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-051602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Richards JW, DiFranza JR, Fletcher C, et al. RJ Reynolds’ “Camel Cash”: another way to reach kids. Tob Control. 1995;4(3):258–260. doi.org/10.1136/tc.4.3.258. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Coeytaux RR, Altman DG, Slade J. Tobacco promotions in the hands of youth. Tob Control. 1995;4(3):253–257. doi.org/10.1136/tc.4.3.253. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sumner W, Dillman DG. A fist full of coupons: cigarette continuity programmes. Tob Control. 1995;4(3):245–252. doi.org/10.1136/tc.4.3.245. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Choi K, Forster J. Tobacco direct mail marketing and smoking behaviors in a cohort of adolescents and young adults from the U.S. Upper Midwest: a prospective analysis. Nicotine Tob Res. 2014;16:886–889. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntu013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Altman DG, Levine DM, Coeytaux R, et al. Tobacco promotion and susceptibility to tobacco use among adolescents aged 12 through 17 years in a nationally representative sample. Am J Public Health. 1996;86(11):1590–1593. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.86.11.1590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Choi K, Forster J. Frequency and characteristics associated with exposure to tobacco direct mail marketing and its prospective effect on smoking behaviors among young adults from the US Midwest. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(11):2179–183. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Choi K, Hennrikus D, Forster J, et al. Receipt and redemption of cigarette coupons, perceptions of cigarette companies and smoking cessation. Tob Control. 2013;22:418–422. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2012-050539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lewis MJ, Delnevo CD, Slade J. Tobacco Industry Direct Mail Marketing and Participation by New Jersey Adults. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(2):257–259. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.2.257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lewis MJ, Manderski MT, Delnevo CD. Tobacco industry direct mail receipt and coupon use among young adult smokers. Prev Med. 2015;71:37–39. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.11.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miech RA, Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, et al. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2014: Volume I, Secondary school students. 2014 http://monitoringthefuture.org/pubs/monographs/mtf-vol1_2014.pdf; Accessed August 30, 2016.

- 30.Flores G. Technical report-racial and ethnic disparities in the health and health care of children. Pediatrics. 2010;125(4):e979–e1020. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-0188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lau M, Lin H, Flores G. Racial/ethnic disparities in health and health care among U.S. adolescents. Health Services Research. 2012;47(5):2031–2059. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2012.01394.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harris JK, Beatty K, Leider JP, et al. The double disparity facing rural local health departments. Annu Rev of Public Health. 2016;37:167–184. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031914-122755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cornelius ME, Driezen P, Hyland A, et al. Trends in cigarette pricing and purchasing patterns in a sample of US smokers: Findings from the ITC US surveys (2002–2011) Tob Control. 2015;24(03):iii4–iii10. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Federal Trade Commission. Federal trade commission cigarette report for 2012. 2015 https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/documents/reports/federal-trade-commission-cigarette-report-2012/150327-2012cigaretterpt.pdf; Accessed August 30, 2016.

- 35.Tobacco Control Legal Consortium. Raising the minimum legal sales age for tobacco and related products Tips and tools. 2015 http://publichealthlawcenter.org/sites/default/files/resources/tclc-guide-minimumlegal-saleage-2015.pdf; Accessed August 30, 2016.

- 36.White MM, Gilpin EA, Emery SL, et al. Facilitating adolescent smoking: who provides the cigarettes? Am J Health Promot. 2005;19(5):355–360. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-19.5.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Forster JL, Wolfson M. Youth access to tobacco: policies and politics. Annu Rev of Public Health. 1998;19:203–235. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.19.1.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Action on Smoking on Health. ASH briefing: The UK ban on tobacco advertising. 2006 http://www.ash.org.uk/files/documents/ASH_525.pdf; Accessed March 13, 2016.

- 39.Tobacco Control Legal Consortium. Regulatory Options for Electronic Cigarettes. 2013 http://publichealthlawcenter.org/sites/default/files/pdf/tclc-fs-regulatory-options-e-cigarettes-2013.pdf; Accessed August 30, 2016.