Abstract

Guided by the stress process model (SPM), this study investigated the direct and indirect pathways of primary (negative self-image and life stress), secondary stressors (family communication strain) and family coping (external and internal) on mental health outcomes among Chinese- and Korean-American breast cancer survivors (BCS). A total of 156 Chinese- and Korean-American BCS were surveyed. Results showed primary and secondary stressors had a negative effect on better mental health outcomes. External coping was associated with better mental health. Family communication strain mediated the relationship between life stress and mental health outcomes. External coping mediated the relationship between family communication strain and mental health outcomes. Multi-group analysis revealed the stress process did not differ across ethnic groups. Findings suggest the SPM may be applicable to understand the stress process of Chinese-and Korean-American BCS and provide valuable insight into the role of family communication and external coping on mental health outcomes.

Keywords: Breast cancer survivor, Asian-American, Stress process, Quality of life, Family coping

Background

Breast cancer is the most frequently diagnosed cancer among Asian-American women [1]. Given the recent increase in breast cancer incidence among Asian-Americans and their highest 5-year survival rates (91.4 %) [2], the numbers of breast cancer survivors (BCS) in the Asian-Americans continue to increase substantially. These trends in prevalence and survivorship emphasize the need for immediate attention for the Asian-American women living with and beyond breast cancer.

Breast cancer treatment and the following survivorship care can present new challenges and stresses for individuals and their families. Research investigating BCS consistently finds that various physical/emotional stressors are prevalent among women with breast cancer [3, 4]. Exposure to these stressors has been linked to deterioration in mental health and worse quality of life [5, 6]. Additionally, researchers have found that the associations between stressors and mental health outcomes may be influenced by family’s support (e.g., family communication, family coping) [7].

Although the BCS’ mental health outcomes and its predictors have been extensively studied among Whites and African-Americans, little is known about the mental health and stress process of Asian-American BCS. Few studies investigating Asian-American women with breast cancer found that they deal with substantial challenges posed by breast cancer- and life-related stresses [8, 9]. Thus, Asian-American women may be at particular risk for having poor mental health, such as depression [10]. In previous research, Asian-cultural beliefs and family have been shown to play an important role in their breast cancer experience and these resulted in ethnic differences [8]. Given the differences in cultural beliefs and Asian’s valuing the family, Asian-American BCS may respond differently to their stress. In addition, their family communication and coping may differ in certain ways in relation to stress process. It is therefore important to understand Asian-American BCS’s stressors/challenges as well as stress processes impacting their mental health. In this study, we specifically focus on the rapidly growing Chinese- and Korean-American BCS groups.

Stress Process Model (SPM)

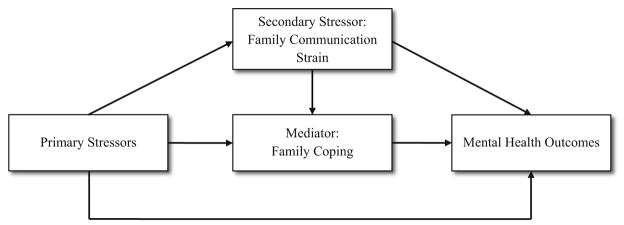

The SPM, one of the most widely used models to guide social scientific thinking about stressors and the interpretation of their effects [11], provides the framework for developing a model of stress process that may be applicable to BCS. The SPM designates three primary features: sources of stressors (primary and secondary), mediators (coping), and outcomes of the stressors [12]. The SPM was originally developed for caregivers, however, it has also been validated in people with chronic illness such as cancer [13, 14]. Asian BCS may deal with similar stressors (e.g., caring for themselves and family demands) that caregivers experience, which influence their mental health outcomes. Their perceived coping mechanisms may serve to mediate the impact of primary and/or secondary stressors on health outcomes (Fig. 1). In sum, the SPM provides key pathways to understand how BCS’ stressors turn into distress and how coping mechanisms may act as a mediator between stressors and mental health outcomes.

Fig. 1.

Study conceptual model

Primary Stressors

Stressors are multifaceted phenomena and involve complex processes. Since this study focuses on the BCS who have completed treatment and have resumed their daily lives, breast cancer-related self-image and life-related stresses were considered as primary stressors. Breast cancer treatments often lead to problems with body image (loss of self-confidence regarding appearance), thus self-image is known as a major concern of BCS, including Asian [8, 15]. The survivors also encounter life-related stressors including life-event stress (death of family member) [16], financial [3], and interpersonal role [3]. The literature consistently found that individuals exposed to these stressors tend to have poor mental health [16, 17].

Secondary Stressors

Primary stressors often are accompanied by secondary stressors. For example, according to Hilton and Koop [18], the stressor (e.g., life-threatening event) evokes demands on family communication and frequently leads to communication strains. Cancer survivors and their families often encounter communication problems when exchanging opinions regarding life- and cancer-related concerns [19, 20]. To illustrate, BCS who undergo mastectomy may feel less attractive and those internalized negative thoughts may lead to avoidance in communication, which in turn could produce family communication strain. Therefore, family communication strain can be seen as a secondary stressor, which is drawn from the primary stressors and it may play a significant role in BCS’ stress process.

Family Coping

Family coping is defined as the specific problem solving strategies designed to maintain the family as a whole and initiate efforts to resolve stressful life-events [21, 22]. Previous studies highlighted the direct and indirect effects of coping on health outcomes in cancer populations [23, 24]. The links between family coping and mental health outcomes among Chinese- and Korean-American BCS are currently unknown. However, considering the benefits of family coping on mental health among people with chronic illness [25] and the importance of families in Chinese and Korean cultures, their perceived family coping may be a significant factor in understanding the stress process.

Chinese- and Korean-Americans BCS

Chinese- and Korean-Americans are ethnically distinct Asian subgroups in several ways (e.g., language). However, these two ethnic groups have certain similar culture characteristics. Chinese and Korean groups have shared cultural values arising from Confucianism, Collectivism, and Familism to a great extent, specifically in regards to valuing family [26, 27]. Given the importance of family in Chinese and Korean cultures, it is possible that family communication and family coping may play important roles in their stress process and these two BCS groups may have similar ways of coping with stress. Because no previous studies addressed the stress process between the two groups, this study was designed to examine whether the stress process in the two groups is similar or different to further investigate the importance of cultural values in the stress process beyond ethnicity.

Study Purposes

The purpose of this study was to develop an understanding of the stress process of Chinese- and Korean-American BCS. Based on the SPM, the study investigated (1) the direct and indirect relationships among primary stressors (negative self-image and life stress), a secondary stressor (family communication strain), family coping (external and internal), and mental health outcomes and (2) whether the pathways differ between the two ethnic groups.

Methods

Participants

A total of 156 survivors (85 Chinese- and 71 Korean-Americans), who were 6 months to 6.5 years post-diagnosis, were recruited from the California Cancer Registry and local hospitals in Los Angeles County. The study procedures have been presented in detail elsewhere [28]. Eligibility criteria included 1) self-identified as Chinese or Korean; 2) aged ≥ 18 years; 3) stage 0–III breast cancer; and 4) with no other cancer diagnosis. The study materials were provided in the participants’ preferred language (English, Chinese, or Korean). All study procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the Case Western Reserve University and the City of Hope.

Measures

Mental Health Outcomes

Three subscales of widely used mental health-related outcomes were employed to assess both positive and negative facets of mental health status. First, the Brief Symptom Inventory-18 (BSI-18) Depression subscale consists of six items (e.g., hopelessness) scored on a 5-point Likert scale [29]. Responses were reverse-scored and summed (range 0–24); higher scores indicate lower depression. Second, the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Breast (FACT-B) Emotional Well-Being subscale consists of 1 positively worded and 5 negatively worded (e.g., sad) items scored on a 5-point Likert scale [30]. Because the positively worded item had an insufficient factor loading of less than .30, only negatively worded items were used. The negatively worded items were reverse scored and then all scores were summed (range 0–20); higher scores represent greater emotional well-being. Third, the Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36) Vitality subscale consists of four items (e.g., energy) and is scored as a summated rating scale (range 4–24) [31]; higher scores indicate greater vitality. Cronbach’s alphas were .88 for depression, .79 for emotional well-being, and .83 for vitality.

Primary Stressor (Negative Self-Image and Life Stress)

Negative self-image was measured using two items (e.g. “I feel sexually attractive” and “I am able to feel like a woman”) of the FACT-B Additional Concerns subscale. The mean composite score was computed, with higher scores indicating more negative self-image. Life stress was measured by the Urban Life Stress Scale assessing the level of life-related stress for the past 3-month [32]. Based on the factor loadings from this sample and suggested stressor structures from the previous studies [9], a three-factor structure was selected and named as “functional stress” (e.g., finances, job situation; 3-item), “stressful life-events” (e.g., illness of someone close; 2-item), and “role stress” (e.g., parenting; 3-item). Mean composite scores for each factor were generated, with the higher scores indicating greater stress (α = .74, .87, and .61 respectively).

Secondary Stressor (Family Communication Strain)

The Family Communication Scale of the Family Adaptability and Cohesion Evaluation (FACES-IV) [33] and the Family Avoidance of Communication about Cancer (FACC) [7] Scales were used to assess both general and cancer-specific family communication problems. A composite score was created by averaging the z scores of both measures, with greater scores representing higher communication strain (α = .93).

Family Coping

Family coping was measured by the Family Crisis Oriented Personal Scale (F-COPES) which assesses a family’s problem-solving strategies in response to family problems/difficulties and includes 3 external (use of outside resources) and 2 internal family coping strategies (utilize the family’s internal strengths/resources) [34]. Based upon current factor loadings and a previous study that shows the modified factor structure of the F-COPES for Chinese- and Korean-American BCS [35], this study focused on the following coping: external (6-item acquiring social support from friends/relatives, 3-item acquiring social support from neighbors, and 4-item seeking spiritual support) and internal (8-item reframing) family coping strategies. Another internal family coping (passive appraisal) subscale which showed poor convergent validity for Chinese- and Korean-American BCS was excluded [35]. The summary scores for each external and internal coping were produced, with higher scores indicating greater use of coping (α = .79–.88).

Analysis

Chi square and t-tests were conducted to compare the ethnic differences in demographic and medical characteristics. Analyses of covariance (ANCOVA) were used to assess the differences in study variables between two ethnic groups, controlling for confounders (e.g., cancer stage and time since diagnosis).

Before conducting the structural equation modeling (SEM) analyses, missing data were imputed using an Expectation–Maximization method [36]. The dimensionality of each latent construct was tested by exploratory factor analyses (EFA) and item-level confirmatory factor analyses (CFA). Results from item-level CFA confirmed the factor structures and suggested an adequate fit to the data: mental health outcomes: χ2(85) = 151.01, RMSEA = .071, and CFI = .95; life stress: χ2(17) = 20.64, RMSEA = .037, and CFI = .99; external family coping: χ2(60) = 114.11, RMSEA = .076, and CFI = .95. The overall measurement model was tested with total score-level CFA by creating composite factor scores to reduce the number of SEM parameter estimations.

Based on the theoretical models and results of measurement model testing, the direct and indirect effects were examined with SEM using AMOS 20.0. Multiple fit indices were used for the criteria of identifying model fit, including Chi square, the comparative fit index (CFI), the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). Model fit was considered to be acceptable for CFI of >.90 and <.08 for RMSEA [37]. The Sobel tests were used to confirm the mediating effects. A multi-group analysis within SEM was performed to compare the fit of the model across two ethnic groups. The unconstrained, factor loadings constrained and structural weights constrained models were compared using Chi square difference tests.

Results

Sample Characteristics and Ethnic Group Differences

Participants’ demographic and medical characteristics and the comparison by ethnicity were presented in Table 1. Chi square and t tests revealed no ethnic differences in demographic and medical characteristics, except for cancer stage and time since diagnosis. Results of ANCOVA indicated that there were significant ethnic differences in negative self-image, stressful life-events, and seeking spiritual support (Table 2). Korean-Americans reported having greater negative self-image and greater seeking of spiritual support than Chinese-Americans. Chinese-Americans reported significantly higher levels of life-event stress than did Korean-Americans. However, other study variables did not differ between the two groups.

Table 1.

Demographic and medical characteristics and differences by ethnicity (N = 156)

| Variables | n (%) | χ2 or t test | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Total | Chinese (n = 85) | Korean (n = 71) | ||

| Age, mean (SD) | 55.29 (9.69) | 55.14 (9.73) | 55.46 (9.70) | t = −.21 |

| Age at immigration, M (SD) | 31.41 (12.52) | 31.73 (13.68) | 31.03 (11.06) | t = .35 |

| Time in the U.S., M (SD) | 23.88 (11.66) | 23.41 (12.26) | 24.44 (10.96) | t = −.55 |

| Language use | .99 | |||

| English | 15 (9.6) | 10 (11.8) | 5 (7.0) | |

| Native (Chinese/Korean) | 141 (90.4) | 75 (88.2) | 66 (93.0) | |

| Marital status (married) | 117 (75.0) | 63 (74.1) | 54 (76.1) | .08 |

| Job status (employed) | 83 (54.2) | 41 (49.4) | 42 (60.0) | 1.72 |

| Education | 1.28 | |||

| ≤High school | 42 (26.9) | 26 (30.6) | 16 (22.5) | |

| >High school | 114 (73.1) | 59 (69.4) | 55 (77.5) | |

| Income | 1.80 | |||

| <$25,000 | 57 (39.6) | 35 (44.3) | 22 (33.8) | |

| $25,000–$45,000 | 24 (16.7) | 12 (15.2) | 12 (18.5) | |

| >$45,000–$75,000 | 26 (18.1) | 14 (17.7) | 12 (18.5) | |

| >$75,000 | 37 (25.7) | 18 (22.8) | 19 (29.2) | |

| Cancer stage | 15.11** | |||

| 0 | 11 (7.1) | 10 (11.8) | 1 (1.4) | |

| I | 56 (35.9) | 22 (25.9) | 34 (47.9) | |

| II | 68 (43.6) | 44 (51.8) | 24 (33.8) | |

| III | 21 (13.5) | 9 (10.6) | 12 (16.9) | |

| Years since diagnosis, M (SD) | 3.49 (1.47) | 3.13 (1.47) | 3.91 (1.37) | t = −3.39** |

| Comorbidity differencea, M (SD) | 1.47 (3.31) | 1.68 (3.15) | 1.23 (3.49) | t = .29 |

| Chemotherapy (yes) | 106 (68) | 62 (73) | 44 (62) | 2.14 |

| Mastectomy (yes) | 83 (53) | 48 (57) | 35 (49) | .80 |

| Surgery without reconstruction (yes) | 133 (85) | 72 (85) | 61 (86) | .05 |

p < .01

Comorbidity difference = comorbidity (current) − comorbidity (before cancer diagnosis)

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics for the study variables and differences by ethnicity (N = 156)

| Variables | M (SD) | Fa | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Number of items | Range | Total | Chinese (n = 85) | Korean (n = 71) | ||

| Negative self-image | 2 | 0–8 | 2.37 (.99) | 2.15 (.98) | 2.59 (.96) | 5.58* |

| Life stress | ||||||

| Functional stress | 3 | 1–5 | 2.19 (1.06) | 2.21 (1.02) | 2.18 (1.10) | .05 |

| Stressful life-event | 3 | 1–5 | 2.00 (1.09) | 2.20 (1.18) | 1.76 (.92) | 6.74* |

| Role stress | 2 | 1–5 | 1.19 (.91) | 1.97 (.95) | 1.84 (.87) | 1.22 |

| Communication strain | 15 | 15–75 | 33.42 (12.84) | 34.35 (12.96) | 32.30 (12.69) | 1.54 |

| External coping | ||||||

| Acquiring support-F/R | 6 | 6–30 | 16.15 (5.41) | 16.90 (4.90) | 15.25 (5.88) | 2.75 |

| Acquiring support-N | 3 | 3–15 | 6.21 (2.79) | 5.88 (2.70) | 6.61 (2.87) | 3.39 |

| Spiritual support | 4 | 4–20 | 12.02 (5.19) | 10.68 (5.26) | 13.63 (4.65) | 14.96*** |

| Internal coping (reframing) | 8 | 8–40 | 27.61 (6.33) | 27.30 (5.97) | 27.99 (6.75) | .98 |

| Mental health outcomes | ||||||

| Emotional well-being | 5 | 0–20 | 15.63 (3.99) | 15.28 (4.06) | 16.05 (3.88) | 1.60 |

| Depression | 6 | 0–24 | 18.97 (4.89) | 19.63 (4.96) | 18.18 (4.72) | 2.63 |

| Vitality | 4 | 4–24 | 15.27 (4.07) | 15.68 (4.01) | 14.78 (4.13) | 1.16 |

p < .05;

p < .001

Two covariates (years since diagnosis and cancer stage) were selected on the basis of results from univariate analyses examining differences in demographic and medical characteristics by ethnicity

Measurement Model

A CFA was conducted on three latent constructs, each comprised of three observed traits: mental health outcomes (depression, emotional well-being, and vitality); life stress (functional stress, stressful life-events, and role stress); and external family coping (acquiring social support from friends/relatives, acquiring social support from neighbors, and seeking spiritual support). The model represented a poor fit (χ2(24) = 73.81, p = .000, RMSEA = .116, and CFI = .95), thus modification to the initial measurement model was employed based on modification indices and theoretical considerations. The model was modified by adding a measurement error covariance between acquiring social support from friends/relatives and seeking spiritual support. The modified model represented an acceptable fit with the data (χ2(23) = 45.31, p = .004, RMSEA = .079, and CFI = .98) and significantly improved the model fit compared to the initial model (Δχ = 28.51, Δdf = 1, p = .001). Hence, the modified model was selected as a measurement model.

The Direct and Indirect Relationships of Predictors on Mental Health Outcomes

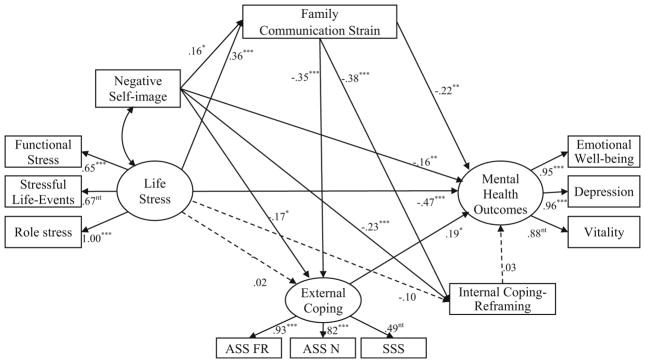

SEM was performed to test the hypothesized relationships among negative self-image, life stress, family communication strain, external and internal family coping, and mental health outcomes (Fig. 2). The proposed structural model provided an adequate fit to the data (χ2(77) = 114.19, p = .004, RMSEA = .056, and CFI = .97). The model explained 57.2 % of the variance in mental health outcomes for Chinese- and Korean-American BCS. Figure 2 presents the standardized path coefficients that refer to the structural relationships among the study variables.

Fig. 2.

Standardized path estimates for structural model. The solid lines indicate significant paths. Cancer stage, comorbidity difference, and breast surgery without reconstruction were controlled. ASS_FR: Acquiring social support from friends/relatives; ASS_N: Acquiring social support from neighbors; SSS: Seeking spiritual support. *p < .05; **p <.01; ***p < .001. nt not tested

Consistent with the SPM, several significant direct pathways were found. Greater primary stressors (negative self-image and life stress) were associated with higher family communication strain. Negative self-image was negatively associated with external and internal family coping use. Greater primary stressors were also associated with poorer mental health. In addition, greater secondary stressor (family communication strain) had negative effects on external and internal family coping use and mental health outcomes. Worth noticing is that use of external family coping had a direct effect on mental health outcomes, whereas internal family coping had no direct effect on mental health outcomes.

Second, two significant indirect (mediating) pathways were found: 1) family communication strain significantly mediated the relationship between life stress and mental health outcomes; and 2) external family coping mediated the relationship between family communication strain and mental health outcomes. The Sobel tests confirmed that these indirect effects were significant (z = −2.81, p < .01 and z = −2.00, p <.05, respectively). These indicate that Chinese- and Korean-American BCS with life stress would have worsened mental health outcomes through family communication strain and those with family communication strain would have improved mental health outcomes through external family coping.

Multi-group Analysis

Preliminary analyses tested the SPM in Chinese- and Korean-American groups separately and determined that the fits were adequate: χ2(77) = 86.09, p = .22, RMSEA = .037, and CFI = .99 and χ2(77) = 112.37, p = .01, RMSEA = .078, and CFI = .94, respectively. Multi-group SEM analyses were then conducted to examine whether the SPM differs across ethnic groups. First, the model which all factor loadings were constrained and the unconstrained model fits were compared. The Chi square change was not significant (Δχ2 = 11.34, Δdf = 8, p = .18), indicating the latent constructs were represented equivalently across the two groups. Next, the factor loadings constrained model and the model which all structural paths were constrained were compared. The Chi square change did not differ (Δχ2 = 12.83, Δdf = 14, p = .54), indicating structural paths were equal across the two groups. The findings indicate equivalence of the SPM models across ethnic groups, suggesting that the stress process does not differ between Chinese- and Korean-American BCS.

Discussion

This study examined the stress process of Chinese- and Korean-American BCS guided by SPM. Results identified several key factors associated with mental health outcomes in Chinese- and Korean-American BCS and also indicated relationships between key factors within a stress process framework. Findings also indicated that there were no significant ethnic differences between the two ethnic groups in the stress process.

As suggested by the SPM and previous studies, greater primary stressors (negative self-image and life stress) were associated with higher family communication strain (e.g., avoidance) [18, 20] and poorer mental health status [17]. Negative self-image was also associated with less use of external and internal coping strategies. These findings are similar to previous research showing that more favorable body image was associated with better capacity to cope [38]. Findings also suggested that family communication problems may cause a lack of initiative to cope with their problems and lead a decrease in coping use. Consistent with previous research [39], family communication strain was associated with poor mental health. As shown in previous research [8, 40], external family coping such as marshaling support from friends/relatives and spiritual support appears to help Chinese- and Korean-American BCS adapt positively, leading to better mental health. Many Chinese- and Korean-American women may encounter barriers (e.g., limited English proficiency) and have limited access to broad support systems (e.g., public services and health care systems) [41, 42]. Therefore, informal support networks provided by relatives, friends, neighbors, and religious support may serve a central role in supporting Chinese- and Korean-American BCS. This implies the beneficial effects of using external family coping in Chinese- and Korean-American BCS and points to the potential importance of considering external family coping to enhance their psychological well-being.

Although the direct relationships in the SPM were generally supported, the associations of life stress with external and internal coping were not. It is possible that the Chinese- and Korean-American BCS may be relatively less likely to disclose sensitive family issues (e.g., financial issue and stressful family events) and may hesitate to use outside networks to cope with their own family stresses in order to maintain group harmony [43]. Additionally, the insignificant relationship between internal family coping (reframing) and mental health outcomes seem inconsistent with previous research on other ethnicity [44]. Reframing, which is a cognitive reappraising strategy in order to change one’s emotional reaction such as optimistic thoughts, may not play a significant role in mental health of Chinese- and Korean-American BCS. It is plausible that Chinese- and Korean-American BCS might have fatalistic beliefs that one’s situation is in the hands of fate and is inevitable [8, 45]. Consequently, they may passively accept problematic situations and a reappraisal of stressors may not influence their mental health outcomes. Although family coping appears as important coping methods for Asian-Americans [46], little is known about internal family coping in this population. Therefore, further research is needed to clarify the impact of internal family coping on mental health by exploring diverse coping strategies used by Chinese- and Korean-American BCS.

Mediating relationships posited in the SPM were also validated in this study. Such findings suggest that improvement of family communication ability is an important mechanism through which life stress contributes to mental health outcomes. Study findings also extend the previous works that posited mediating role of coping between strain and mental health outcomes [47, 48]. Results suggest that greater family communication strain could make it difficult for Chinese- and Korean-American BCS to utilize external family coping; these in turn might be associated with worsened mental health outcomes.

Limitations

There are several limitations to this study. Firstly, due to a relatively small sample size, caution is needed in generalizing study findings. Secondly, although the present study considered time differences in study measures (asking about stress over the past 3-month and mental health status for the past week), we should be aware of the cross-sectional nature of the study design. Lastly, secondary data limit the measures of negative self-image and stressful life-events which consisted of two items. Future research therefore should employ measures that expand beyond the items, and identify stressors that may be relevant to Chinese- and Korean-American BCS.

Conclusion

This study has contributed to the current knowledge by investigating the linkages between primary and secondary stressors, mediators, and mental health outcomes among understudied Chinese- and Korean-American BCS. To our knowledge, this study is the first to explicitly examine the stress process of Chinese- and Korean-American BCS based on SPM. The overall findings highlight that the SPM may be appropriate to investigate and interpret the experiences of Chinese- and Korean-American BCS. The results provide greater insight into the impact of various individual and family-related factors in the SPM on mental health outcomes. The SPM provided the rationale for targeting culturally tailored interventions that promote better mental health outcomes. For example, results imply that providing interactive educational programs aimed at improving post-cancer self-image and helping Chinese-and Korean-American BCS to relieve perceived life stress may be beneficial in reducing family communication strain and promoting psychological well-being. Additionally, developing psycho-educational interventions designed specifically to improve family communication skills and to encourage use of external family support systems (e.g., acquiring support from friends/relatives) would improve the mental health status of Chinese- and Korean-American BCS. Researchers and practitioners should acknowledge the need for such interventions specifically for Chinese-and Korean-American women who have undergone breast cancer treatment.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by NIH/NCI, 1R03CA139941 (PI: Jung-won Lim, PhD). Min-So Paek is supported by the Comprehensive Cancer Center of Wake Forest University Cancer Control Traineeship, NCI/NIH grant #R25CA122061 (PI: Nancy E. Avis).

References

- 1.Gomez SL, Noone A-M, Lichtensztajn DY, Scoppa S, Gibson JT, Liu L, et al. Cancer incidence trends among Asian American populations in the United States, 1990–2008. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105(15):1096–110. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djt157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Cancer Society. Breast cancer facts and figures 2013–2014. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schnipper HH. Life After Breast Cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(9 suppl):104–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.01.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thewes B, Butow P, Girgis A, Pendlebury S. Assessment of unmet needs among survivors of breast cancer. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2004;22(1):51–73. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andrykowski MA, Lykins E, Floyd A. Psychological health in cancer survivors. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2008;24(3):193–201. doi: 10.1016/j.soncn.2008.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Howard-Anderson J, Ganz PA, Bower JE, Stanton AL. Quality of life, fertility concerns, and behavioral health outcomes in younger breast cancer survivors: a systematic review. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2012;104(5):386–405. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djr541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mallinger JB, Griggs JJ, Shields CG. Family communication and mental health after breast cancer. Eur J Cancer Care. 2006;15(4):355–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2006.00666.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ashing-Giwa K, Padilla G, Tejero J, Kagawa-Singer M. Understanding the breast cancer experience of Asian American women. Psycho-Oncology. 2003;12(1):38–58. doi: 10.1002/pon.632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ashing-Giwa K, Lim JW. Exploring the association between functional strain and emotional well-being among a population-based sample of breast cancer survivors. Psycho-Oncology. 2010;19(2):150–9. doi: 10.1002/pon.1517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xiaoli C, Ying Z, Wei Z, Kai G, Zhi C, Wei L, et al. Prevalence of depression and its related factors among Chinese women with breast cancer. Acta Oncol. 2009;48(8):1128–36. doi: 10.3109/02841860903188650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pearlin LI. The stress process revisited: Reflections on concepts and their interrelationships. In: Aneshensel CS, Phelan JC, editors. Handbook of the sociology of mental health. Handbooks of sociology and social research. New York, NY: Springer; 1999. pp. 395–415. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pearlin LI, Mullan JT, Semple SJ, Skaff M. Caregiving and the stress process: an overview of concepts and their measures. Gerontologist. 1990;30(5):583–94. doi: 10.1093/geront/30.5.583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deimling GT, Bowman KF, Sterns S, Wagner LJ, Kahana B. Cancer-related health worries and psychological distress among older adult, long-term cancer survivors. Psycho-Oncology. 2006;15(4):306–20. doi: 10.1002/pon.955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Land H, Hudson SM, Stiefel B. Stress and depression among HIV-positive and HIV-negative gay and bisexual AIDS care-givers. AIDS Behav. 2003;7(1):41–53. doi: 10.1023/a:1022509306761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reich M, Lesur A, Perdrizet-Chevallier C. Depression, quality of life and breast cancer: a review of the literature. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;110(1):9–17. doi: 10.1007/s10549-007-9706-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kornblith AB, Herndon JE, Zuckerman E, Viscoli CM, Horwitz RI, Cooper MR, et al. Social support as a buffer to the psychological impact of stressful life events in women with breast cancer. Cancer. 2001;91(2):443–54. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20010115)91:2<443::aid-cncr1020>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Karakoyun-Celik O, Gorken I, Sahin S, Orcin E, Alanyali H, Kinay M. Depression and anxiety levels in woman under follow-up for breast cancer: relationship to coping with cancer and quality of life. Med Oncol. 2010;27(1):108–13. doi: 10.1007/s12032-009-9181-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hilton BA, Koop PM. Family communication patterns in coping with early breast cancer. West J Nurs Res. 1994;16(4):366–91. doi: 10.1177/019394599401600403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goldsmith DJ, Miller LE, Caughlin JP. Openness and avoidance in couples communicating about cancer. In: Beck C, editor. Communication Yearbook. Vol. 31. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 2007. pp. 62–115. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang AY, Siminoff LA. Silence and cancer: why do families and patients fail to communicate? Health Commun. 2003;15(4):415–29. doi: 10.1207/S15327027HC1504_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McCubbin HI, Joy CB, Cauble A, Comeau J, Patterson J, Needle R. Family stress and coping: a decade review. J Marriage Fam. 1980;42(4):855–71. [Google Scholar]

- 22.McCubbin HI, Larsen AS, Olson DH. Family Crisis Oriented Personal Evaluation Scales (F-COPES) St Paul: University of Minnesota Press; 1985. Family inventories; pp. 143–159. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hack TF, Degner LF. Coping responses following breast cancer diagnosis predict psychological adjustment three years later. Psycho-Oncology. 2004;13(4):235–47. doi: 10.1002/pon.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Manne S, Glassman M. Perceived control, coping efficacy, and avoidance coping as mediators between spousal unsupportive behaviors and psychological distress. Health Psychol. 2000;19(2):155–64. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.19.2.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Myers RM, Balsamo L, Lu X, Devidas M, Hunger SP, Carroll WL, et al. A prospective study of anxiety, depression, and behavioral changes in the first year after a diagnosis of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancer. 2014 doi: 10.1002/cncr.28578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Park M, Chesla C. Revisiting Confucianism as a conceptual framework for Asian family study. J Fam Nurs. 2007;13(3):293–311. doi: 10.1177/1074840707304400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shin DC. Confucianism and democratization in east Asia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lim J-W, Paek M-S. The relationship between communication and health-related quality of life in survivorship care for Chinese-American and Korean-American breast cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer. 2013;21(4):1157–66. doi: 10.1007/s00520-012-1641-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Derogatis LR. Brief symptom inventory 18: administration, scoring, and procedures manual (Clinical Psychometric Research) Minneapolis, MN: NCS Pearson Inc; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brady MJ, Cella DF, Mo F, Bonomi AE, Tulsky DS, Lloyd SR, et al. Reliability and validity of the functional assessment of cancer therapy-breast quality-of-life instrument. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15(3):974–86. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.3.974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ware JE, Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36): I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30(6):473–83. doi: 10.2307/3765916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ashing-Giwa K, Ganz PA, Petersen L. Quality of life of African-American and white long term breast carcinoma survivors. Cancer. 1999;85(2):418–26. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19990115)85:2<418::aid-cncr20>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Olson D. FACES IV and the circumplex model: validation study. J Marital Fam Ther. 2011;37(1):64–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-0606.2009.00175.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McCubbin HI, Larsen A, Olson DH. Family crisis orientated personal evaluation scales (F-COPES) In: McCubbin HI, Thompson AI, editors. Family assessment inventories for research and practice. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin-Madison; 1987. pp. 193–207. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lim J-w. Townsend A: cross-Ethnicity measurement equivalence of family coping for breast cancer survivors. Res Soc Work Pract. 2012;22(6):689–703. doi: 10.1177/1049731512448933. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Allison P. Missing data techniques for structural equation modeling. J Abnorm Psychol. 2003;112:545–57. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.112.4.545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. 3. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pikler V, Winterowd C. Racial and body image differences in coping for women diagnosed with breast cancer. Health Psychol. 2003;22(6):632–7. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.22.6.632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Donovan-Kicken E, Caughlin JP. Breast cancer patients’ topic avoidance and psychological distress: the mediating role of coping. J Health Psychol. 2011;16(4):596–606. doi: 10.1177/1359105310383605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kraemer LM, Stanton AL, Meyerowitz BE, Rowland JH, Ganz PA. A longitudinal examination of couples’ coping strategies as predictors of adjustment to breast cancer. J Fam Psychol. 2011;25(6):963–72. doi: 10.1037/a0025551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Flores G. Language barriers to health care in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(3):229–31. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp058316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wong ST, Yoo GJ, Stewart AL. Examining the types of social support and the actual sources of support in older Chinese and Korean immigrants. Int J Aging Hum Dev. 2005;61(2):105–21. doi: 10.2190/AJ62-QQKT-YJ47-B1T8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Taylor SE, Sherman DK, Kim HS, Jarcho J, Takagi K, Dunagan MS. Culture and social support: Who seeks it and why? J Pers Soc Psychol. 2004;87(3):354–62. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.87.3.354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sears SR, Stanton AL, Danoff-Burg S. The yellow brick road and the emerald city: benefit finding, positive reappraisal coping and posttraumatic growth in women with early-stage breast cancer. Health Psychol. 2003;22(5):487–97. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.22.5.487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kim J, Menon U, Wang E, Szalacha L. Assess the effects of culturally relevant intervention on breast cancer knowledge, beliefs, and mammography use among Korean American women. J Immigr Minor Health. 2010;12(4):586–97. doi: 10.1007/s10903-009-9246-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yoo G, Levine E, Pasick R. Breast cancer and coping among women of color: a systematic review of the literature. Support Care Cancer. 2014;22(3):811–24. doi: 10.1007/s00520-013-2057-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Folkman S, Lazarus RS, Gruen RJ, DeLongis A. Appraisal, coping, health status, and psychological symptoms. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986;50(3):571–9. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.50.3.571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Manne S, Pape S, Taylor K, Dougherty J. Spouse support, coping, and mood among individuals with cancer. Ann Behav Med. 1999;21(2):111–21. doi: 10.1007/BF02908291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]