Abstract

Background

Whilst C-reactive protein (CRP) is an established serum marker of inflammation, its use in gastroenterology has been limited by its poor sensitivity and specificity for GI disease. Faecal calprotectin (FC) has been adopted into mainstream GI practice as a sensitive but non-specific marker of intestinal inflammation. However, stool samples collection for FC can be challenging and the possibility of utilising a sensitive and specific serum biomarker of intestinal inflammation in luminal gastroenterology is an attractive prospect. This work investigates the performance of serum calprotectin (SC) compared to current biomarkers, FC and CRP, in an unselected cohort of patients attending our GI unit.

Methods

Patients attending in and outpatients within an adult GI service who submitted a stool sample for FC analysis were identified. A total of 109 who had a serum sample obtained within one day of stool sample collection had the serum analysed for CRP and SC and the correlation between these biomarkers was investigated.

Results

The intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) between SC, FC and CRP was 0.10, 95% CI − 0.09–0.28 and 0.18, 95% CI − 0.01–0.35, respectively. The ICC between FC and CRP was 0.18, 95% CI − 0.01–0.35.

Conclusions

Our data reveals that there is no significant correlation between SC and FC, nor between SC and CRP in a large unselected cohort of GI patients. Therefore, as a serum biomarker for intestinal inflammation, SC is unlikely to be of clinical utility and the search for an appropriate serum GI biomarker continues.

Keywords: Gastro-intestinal disorders, Clinical studies, Evaluation of new methods, Laboratory methods, Calprotectin

1. Introduction

Sensitive biomarkers of intestinal inflammation are crucially important in gastroenterology for monitoring response to treatment in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and to support a diagnosis of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). In IBD in particular, mucosal healing has become an accepted goal of treatment [1] [2] [3] and there is a need for the availability of sensitive, rapid, reliable, cost effective and non invasive biomarkers to reflect mucosal healing. Colonoscopy remains ‘the gold standard’ for the assessment of terminal ileal and colonic mucosal healing. However it is expensive, time consuming, inconvenient for patients and carries a significant, albeit small, risk of morbidity and mortality, making it unsuitable for frequent serial monitoring of gastrointestinal (GI) disease.

Serum markers of GI inflammation are attractive as they can be requested in the GI clinic as part of a routine panel of bloods that patients with IBD often require to monitor the safety of their long-term medical therapies. The most commonly used serum biomarker in this setting is C-reactive protein (CRP), one of the acute phase proteins, which is widely available and cheap to measure. Although CRP is a responsive marker of inflammation due to its short half life, it is elevated in a variety of inflammatory conditions and therefore lacks specificity and moreover, correlation with mucosal healing in IBD has been shown to be poor [4].

Faecal biomarkers have the potential advantage of increased specificity for GI tract inflammation. Of those studied, faecal calprotectin (FC) is the only one to have become established in mainstream GI practice. Derived from the cytosol of neutrophils, calprotectin is released during cell damage and its resistance to enzymatic degradation means that it can be measured in stool. FC has been shown to correlate well with intestinal micro and macroscopic inflammation [5] [6] [7] [8] but is entirely non-specific, being raised in a variety of inflammatory GI pathologies. FC can be used to differentiate IBD from IBS [9] and is a useful predictor of relapse in IBD [10] [11]. However, collection of stool samples is cumbersome for patients and aesthetically problematic. Stool samples can only rarely be collected fresh in clinic to coincide with clinic appointments and thus samples often require transfer to a central laboratory which can raise logistical issues. If serum calprotectin (SC) was shown to correlate well with faecal calprotectin, then this would be an attractive serum biomarker to check in many patients attending luminal gastroenterology services. There is very little published on the clinical utility of SC in the setting of gastroenterology. There is evidence suggesting correlation with colitis severity in a rodent model [12]. Furthermore, data in Crohn's disease [13] and severe ulcerative colitis (UC) [14] suggests it may perform similarly to CRP as a biomarker. In a pilot study, we have prospectively investigated the performance of SC and compared it to both FC and CRP in an unselected cohort of patients attending our GI unit who were having a FC sample analysed.

2. Methods

Between July and October 2015, in and out patients within the adult GI service at Glasgow Royal Infirmary who submitted a stool sample for FC analysis were prospectively identified. Those patients who had a serum sample obtained within 24 h of stool sample collection were identified and the sample stored at − 80 °C for batch analysis of CRP and SC. Our project was approved with the West of Scotland Research Ethics Committee (REC 14/WS/1035).

FC was measured using a BÜHLMANN quantitative ELISA (BÜHLMAN Laboratories AG, Switzerland) kit on a Grifols Triturus fully automated EIA analyser (Grifols Diagnostics, LA) (intra-assay imprecision CV < 5% over the sample concentration range). SC was measured using the BÜHLMANN quantitative MRP8/14 (Calprotectin) ELISA kit also on the Triturus analyser (intra-assay imprecision CV < 4% over the sample concentration range). Both FC and SC kits utilised a monoclonal antibody. CRP was measured on Architect 8000 (Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, Illinois), intra-assay imprecision CV < 4%.

The laboratory participates in external quality assurance schemes (UKNEQAS General Chemistry for CRP and UKNEQAS Faecal Markers of Inflammation for FC) and performance was acceptable throughout the period of analysis.

Statistical analysis was performed with the use of MedCalc® software (version 15.4; MedCalc Software bvba).

3. Results

In total, 109 patients had their serum analysed for SC and CRP over the four month recruitment period, 68 (62%) of which were female. The mean age of this patient cohort was 51 years (range 18–93 years) and all were patients seen in a secondary care environment (inpatient GI wards and GI clinics). The mean time between the date of receipt of serum and faecal sample was 1.85 days (range 0–6 days). The indications for FC testing were assessment of IBD activity (69, 63%) and assessment of chronic diarrhea symptoms (40, 37%)

Mean SC in this group of patients was 6.67 μg/mL (range: 1.06–24.00 μg/mL). This assay is linear up to 24.00 μg/mL and for the purpose of the statistical analysis, any results > 24.00 μg/mL were arbitrarily assigned a value of 24.00 μg/mL. Mean FC was 362.72 μg/g (range: 30–1800 μg/g). This assay is linear between 30 and 1800 μg/g and any results < 30 or > 1800 were arbitrarily assigned values of 30 and 1800 μg/g, respectively, for statistical purposes. Mean CRP was 15.3 mg/L (range: 1.0–126 mg/L) and any CRP result < 1.0 mg/L was arbitrarily assigned a value of 1.0 mg/L for statistical analysis.

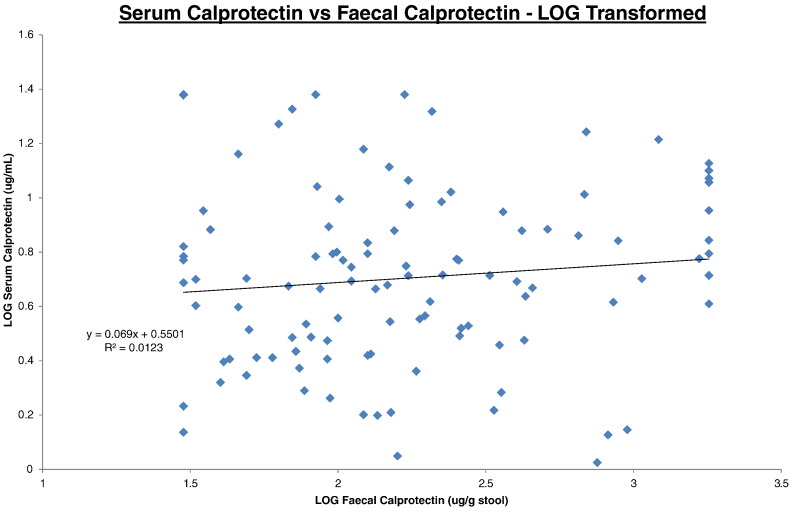

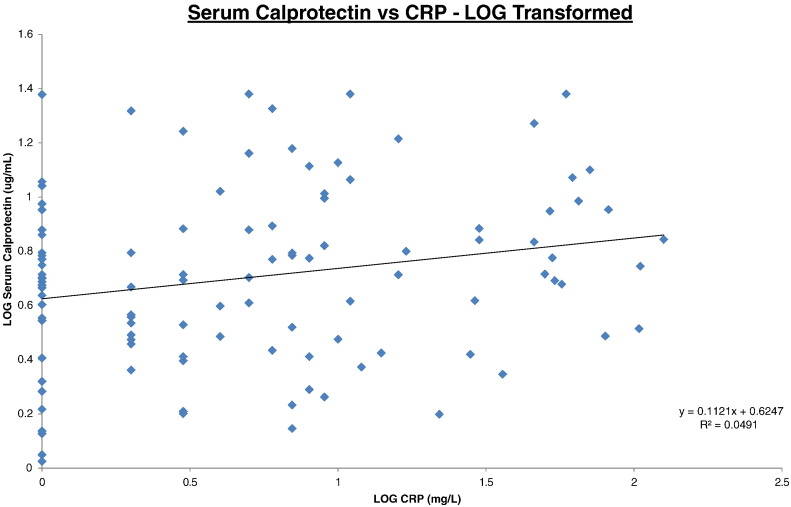

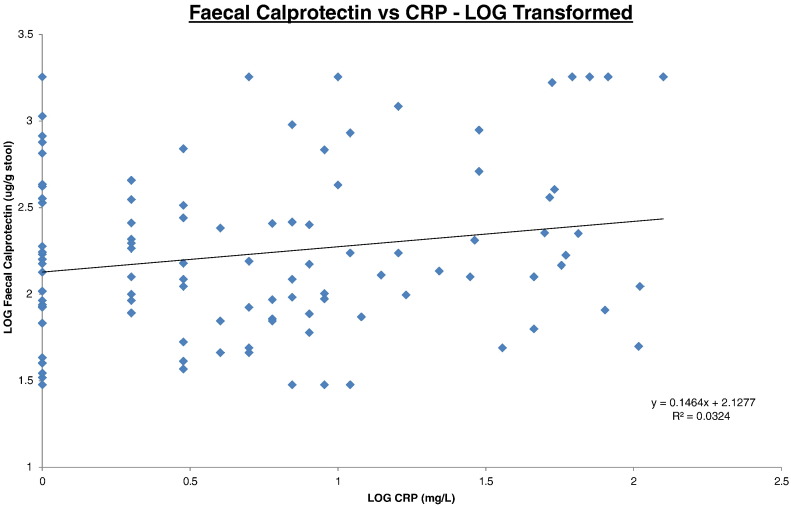

The log transformed correlation datasets are illustrated on Fig. 1, Fig. 2, Fig. 3 for SC/FC, SC/CRP and FC/CRP respectively. Correlations were expressed as intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) and were calculated following logarithm transformation of the data (Table 1). The closer the ICC is to 1 the better the agreement.

Fig. 1.

Serum calprotectin vs faecal calprotectin.

All data was log transformed. Serum calprotectin results (y-axis) were plotted against faecal calprotectin results (x-axis). Trendline, equation and R2 value are depicted on the graph.

Fig. 2.

Serum calprotectin vs CRP.

All data was log transformed. Serum calprotectin results (y-axis) were plotted against CRP results (x-axis). Trendline, equation and R2 value are depicted on the graph.

Fig. 3.

Faecal calprotectin vs CRP.

All data was log transformed. Faecal calprotectin results (y-axis) were plotted against CRP results (x-axis). Trendline, equation and R2 value are depicted on the graph.

Table 1.

Correlations between serum calprotectin, faecal calprotectin and CRP.

| Dataset with 109 patients |

||

|---|---|---|

| ICC | 95% CI | |

| SC compared with FC | 0.10 | − 0.09–0.28 |

| SC compared with CRP | 0.18 | − 0.01–0.35 |

| FC compared with CRP | 0.18 | − 0.01–0.35 |

Excluding data outside the linear range of the three assays created a patient cohort of 73 patients. When the statistical analysis was repeated with this smaller cohort it had no significant effect on the overall statistical outcome thus indicating that assigning arbitrary values did not create a bias in the dataset.

4. Discussion

This pilot dataset of 109 unselected GI patients attending a tertiary referral institution is the largest GI cohort to date to assess the performance of an SC assay. Our data reveal that there is no significant correlation between SC and FC, nor between SC and CRP.

In the context of IBD, calprotectin is produced by both mucosal neutrophils and intestinal epithelial cells and is mainly released in the mucosa and intestinal lumen, which leads to increased calprotectin concentrations in faeces [15]. Indeed, the clinical utility of FC in luminal gastroenterology has been widely demonstrated by our own team and others [10] [16]. However, as neutrophils are the main producers of calprotectin (where it is estimated to account for about 40% of cytosolic protein), increases in its concentration in extracellular fluid have been noted in various other inflammatory conditions as well as IBD including rheumatoid arthritis [17] and cystic fibrosis [18] where serum calprotectin appears to be predictive of clinical course. Therefore, SC depicts a picture of systemic inflammation rather than gut-specific and it is not entirely unexpected that serum and faecal calprotectin do not correlate.

What is perhaps more surprising is that we were unable to demonstrate a correlation between CRP and SC, a finding that is in contrast to some of the limited data currently available [13] [14]. The latter patient cohorts in these datasets differ from our own unselected subjects and include acute severe UC [14] and Crohn's disease patients in clinical remission on combination infliximab/antimetabolic therapy [13]. It may be that the patient cohort used in these studies had a greater proportion of acutely ill patients with more severe disease that is reflected by an increased systemic inflammatory response. Indeed, the median serum calprotectin value was higher in the Crohn's disease patients included in the GETAID [13] study at 8.89 μg/mL compared to the median of our unselected group of patients at 6.67 μg/mL. Furthermore, it is well known that there is significant analytical variability between FC methods [19] and the GETAID paper [13] utilised different assays for both calprotectin and CRP as compared to our own analyses. Also, whilst SC and CRP are both considered as acute phase reactants; their synthesis rate, half-life (5 h for SC compared to 19 h for CRP) and clearance in serum are different and especially in our unselected cohort of GI patients (37% of which do not have an IBD diagnosis), the lack of correlation may relate to several different disease processes occurring concomitantly.

Whilst a single study [12] in a rodent model of colitis suggested that SC correlated well with macro and microscopic disease scores, this has not yet been tested in humans. It was a small study and rodent models of colitis are only approximate surrogate models of IBD, often requiring chemical treatment to induce the colitis, which may or may not be representative of human IBD. Nonetheless this data suggests that a human colonoscopic study looking at SC in IBD is warranted to see if the macro and microscopic correlation, already shown for FC [5], can be replicated with SC.

In conclusion, this pilot work shows that, as a serum biomarker for intestinal inflammation, SC is unlikely to be of clinical utility and the search for an appropriate serum biomarker to replace faecal calprotectin continues. It may be that a more focussed study looking at a specific group of rigorously phenotyped GI patients may provide evidence of a more favourable correlation between the faecal & serum biomarkers.

Competing interests

There are no conflicts of interest associated with this work.

Funding

RKM was awarded a Scientific Development Scholarship in 2014 from the Association of Clinical Biochemistry and Laboratory Medicine Scientific Committee to fund the project. DRG is funded by a personal fellowship from the Chief Scientists Office of the Scottish Government to investigate Inflammatory Bowel Disease.

Ethical approval

This project was approved by the West of Scotland Research Ethics Committee (REC reference 14/WS/1035).

Guarantor

DRG is the guarantor for this work.

Contributorship

RKM and KS conceived the project. RKM collected the samples, validated the SC assay and performed the analysis. RKM and DRG wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors reviewed and edited the manuscript and approved the final version.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge Dr. Sarah Barry, Consultant Biostatistician, Robertson Centre for Biostatistics, University of Glasgow for her advice regarding statistical analysis of the dataset.

References

- 1.Baert F., Moortgat L., Van Assche G., Caenepeel P., Vergauwe P., De Vos M. Mucosal healing predicts sustained clinical remission in patients with early-stage Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 2010;138(2):463–468. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.09.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ardizzone S., Cassinotti A., Duca P., Mazzali C., Penati C., Manes G. Mucosal healing predicts late outcomes after the first course of corticosteroids for newly diagnosed ulcerative colitis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2011;9(6):483–489.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2010.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shah S.C., Colombel J.F., Sands B.E., Narula N. Systematic review with meta-analysis: mucosal healing is associated with improved long-term outcomes in Crohn's disease. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2016;43(3):317–333. doi: 10.1111/apt.13475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miranda-García P., Chaparro M., Gisbert J.P. Correlation between serological biomarkers and endoscopic activity in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.gastrohep.2016.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.D'Haens G., Ferrante M., Vermeire S., Baert F., Noman M., Moortgat L. Fecal calprotectin is a surrogate marker for endoscopic lesions in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2012;18(12):2218–2224. doi: 10.1002/ibd.22917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Røseth A.G., Aadland E., Jahnsen J., Raknerud N. Assessment of disease activity in ulcerative colitis by faecal calprotectin, a novel granulocyte marker protein. Digestion. 1997;58(2):176–180. doi: 10.1159/000201441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sipponen T., Savilahti E., Kolho K.L., Nuutinen H., Turunen U., Färkkilä M. Crohn's disease activity assessed by fecal calprotectin and lactoferrin: correlation with Crohn's disease activity index and endoscopic findings. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2008;14(1):40–46. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schoepfer A.M., Flogerzi B., Seibold-Schmid B., Schaffer T., Kun J.F., Pittet V. Low Mannan-binding lectin serum levels are associated with complicated Crohn's disease and reactivity to oligomannan (ASCA) Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2009;104(10):2508–2516. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schoepfer A.M., Trummler M., Seeholzer P., Seibold-Schmid B., Seibold F. Discriminating IBD from IBS: comparison of the test performance of fecal markers, blood leukocytes, CRP, and IBD antibodies. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2008;14(1):32–39. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Naismith G.D., Smith L.A., Barry S.J., Munro J.I., Laird S., Rankin K. A prospective evaluation of the predictive value of faecal calprotectin in quiescent Crohn's disease. J. Crohns Colitis. 2014;8(9):1022–1029. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2014.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tibble J.A., Sigthorsson G., Bridger S., Fagerhol M.K., Bjarnason I. Surrogate markers of intestinal inflammation are predictive of relapse in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2000;119(1):15–22. doi: 10.1053/gast.2000.8523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cury D.B., Mizsputen S.J., Versolato C., Miiji L.O., Pereira E., Delboni M.A. Serum calprotectin levels correlate with biochemical and histological markers of disease activity in TNBS colitis. Cell. Immunol. 2013;282(1):66–70. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2013.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meuwis M.A., Vernier-Massouille G., Grimaud J.C., Bouhnik Y., Laharie D., Piver E. Serum calprotectin as a biomarker for Crohn's disease. J. Crohns Colitis. 2013;7(12):e678–e683. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2013.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hare N., Kennedy N., Kingstone K., Arnott I., Shand A., Palmer K. Inflammatory bowel disease PTH-082 serum calprotectin: a novel biomarker to predict outcome in acute severe ulcerative colitis? Gut. 2013;p. Suppl 1:A244–A245. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Røseth A.G., Fagerhol M.K., Aadland E., Schjønsby H. Assessment of the neutrophil dominating protein calprotectin in feces. A methodologic study. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 1992;27(9):793–798. doi: 10.3109/00365529209011186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mao R., Xiao Y.L., Gao X., Chen B.L., He Y., Yang L. Fecal calprotectin in predicting relapse of inflammatory bowel diseases: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2012;18(10):1894–1899. doi: 10.1002/ibd.22861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hammer H.B., Odegard S., Syversen S.W. Calprotectin (a major S100 leucocyte protein) predicts 10-year radiographic progression in patients with rheumatoid arthitis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2010;69:150–154. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.103739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gray R.D., Imrie M., Boyd A.C. Sputum and serum calprotectin are useful biomarkers during CF exacerbation. J. Cyst. Fibros. 2010;9:193–198. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2010.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Whitehead S.J., French J., Brookes M.J., Ford C., Gama R. Between-assay variability of faecal calprotectin enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kits. Ann. Clin. Biochem. 2013;50(Pt 1):53–61. doi: 10.1258/acb.2012.011272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]