Abstract

This case addresses the difficulty in the initial diagnosis of severe Crohn’s disease in pregnancy as well as the challenges of instituting remission therapy towards the end of second trimester. The patient’s course was complicated by recurrent hospital admissions and intolerance to diet requiring temporary nasogastric feeding. Medical management included the use of biological agents during pregnancy, which allowed for better symptomatic control. She sustained no further complications and underwent a successful vaginal delivery of a healthy baby at 37 weeks’ gestation.

Keywords: Maternal–fetal medicine

Summary

This case addresses the difficulty in initial diagnosis of severe Crohn’s disease in pregnancy as well as the challenges of instituting remission therapy towards the end of second trimester. The patient’s course was complicated by recurrent hospital admissions and intolerance to diet requiring temporary nasogastric feeding. Medical management included the use of biological agents during pregnancy, which allowed for better symptomatic control. She sustained no further complications and underwent a successful vaginal delivery of a healthy baby at 37 weeks’ gestation.

Background

First presentation of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) in pregnancy is rare, and the diagnosis may be challenging. Completion of confirmatory investigations and disease control may be impacted by safety concerns in pregnancy.

Case

Our case is a 23-year-old multiparous woman with a previous uncomplicated pregnancy resulting in a successful vaginal breech delivery at 39 weeks’ gestation. Her medical history included alopecia areata and erythema nodosum prior to her first pregnancy.

Presentation

During this second pregnancy, she reported being unwell from 10 weeks’ gestation with nausea and vomiting, postprandial abdominal cramps and weight loss. She presented to the emergency department (ED) with general malaise and nausea and vomiting. In view of her history of erythema nodosum, a chest X-ray (CXR) was performed at that time to rule out sarcoidosis and it was normal. She was discharged home. At 20 weeks’ gestation, she was referred by her general practitioner to the gastroenterology clinic for per rectal bleeding and weight loss. Further questioning revealed a two months pre-pregnancy history of postprandial bloating with intermittent diarrhoea. A presumptive diagnosis of IBD was made.

Investigations to confirm IBD, exclude other diagnoses (coeliac disease) and to consider associated pathology (sclerosing cholangitis), were organized. Blood tests for faecal calprotectin were requested. This is a biochemical marker for bowel inflammation, with high sensitivity and variable specificity. It is recommended by National Institute for Health and Care Excellence as an aid in differentiating between IBD and non-IBD.1 In our case, it was found to be 958 mcg/g (50–100 mcg/g). Other inflammatory markers were raised (normal values for third trimester of pregnancy): C-reactive protein (CRP) 88 mg/L (1–10 mg/L) and platelets 498 × 109/L (150–410 × 109/L), while albumin levels were slightly decreased to 23 g/L (23–42 g/L). She underwent an abdominal ultrasound (US) examination as an outpatient which revealed substantial mural thickening of the ascending colon and hepatic flexure and a normal appearance of the biliary tree. Stool cultures were sent subsequently and the results were negative for Escherichia coli 0157, Campylobacter species, Salmonella species, Shigella species and Clostridium difficile. Her vitamin B12 level was 339 ng/L (130–1100 ng/L), her folate level was 2.8 µg/l (2.7–15.0 µg/L) and she was anti-tissue transglutaminase antibody negative. Following her initial clinic appointment, she was started on Mesalamine 2 g/day (also known as Mesalazine).

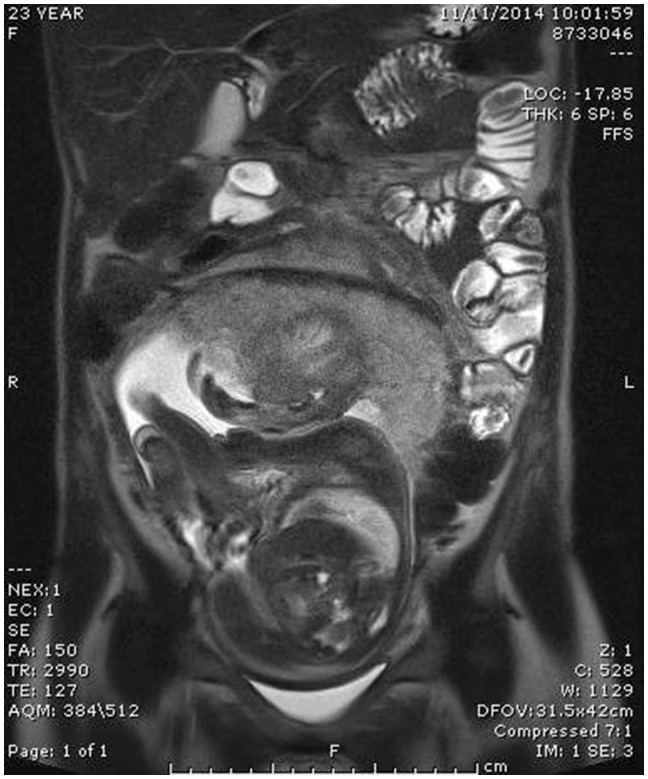

At 25 weeks’ gestation, she was admitted to hospital with cramping abdominal pain, distension and loss of appetite accompanied by a 1 kg weight loss. A course of oral prednisolone was started, following which her symptoms subsided, and she was discharged home. However, four days later she presented via ED with recurrence of symptoms. Faecal calprotectin increased to 7900 mcg/g, matched by a CRP increase to 103 mg/L. Intravenous methylprednisolone 40 mg BD was commenced, followed by a decreasing regime of oral prednisolone. Her clinical picture settled temporarily and was followed by another hospital admission at 28 weeks’ gestation for inability to tolerate any oral intake. As a result she lost a significant amount of weight (from 48.2 kg to 46 kg, 4% total body weight). A nasogastric tube was inserted and a plan for 1500 kcal/day liquid diet was made. Fetal growth was 1.49 kg (44th centile). A magnetic resonance endoscopy (MRE) was arranged at this point. It revealed a displaced terminal ileum and ileo-colic junction with wall thickening accompanied by submucosal oedema in the terminal ileal segment. There was no evidence of abscess formation or obstruction despite upstream ileal dilatation (see Figure 1). A diagnosis of ileal tuberculosis or lymphoma was considered unlikely as no infiltration was described on MRE. In addition, our patient did not belong to a high-risk group and had a normal CXR at 10 weeks’ gestation in this pregnancy.

Figure 1.

MR enterography in pregnancy showing wall thickening and submucosal oedema of the distal and terminal ileum.

Treatment

An obstetric multidisciplinary team meeting was convened to discuss her options for therapy. A decision was taken to start infliximab in the third trimester of pregnancy, as it was felt that Azathioprine would take too long to initiate an effect, which can take between three and four months. She was advised against breastfeeding because of the theoretical risk of increased childhood infections, despite evidence that infliximab excretion in the breast milk is negligible. No association with any infant complications such as growth delay and recurrent infections has been found when infliximab was used as sole agent during pregnancy.2

In response to infliximab her appetite improved and she started to tolerate an oral diet. Her weight increased to 50 kg. At 37 weeks’ gestation, she went into spontaneous labour and had a vaginal delivery of a live baby (birth weight 2.86 kg, 44th centile) with good Apgar scores.

Despite an initial response to biological treatment, she was later deemed a non-responder and required surgical management. Eight months postpartum, she underwent a laparoscopic right hemicolectomy for recurrent obstructive symptoms. Four months post-surgery she underwent, a colonoscopy which revealed anastomotic ulcerations and active ileum disease. A histological diagnosis of Crohn’s disease was made on biopsies. She was unable to tolerate azathioprine due to side effects and so it was restarted at 75% of initial dose with the addition of allopurinol.

Discussion

Our case presented two major challenges, namely the most appropriate confirmatory tests and treatment options in new onset IBD during pregnancy.

The options for investigations of presumed IBD in the antenatal period include:

MR enterography (MRE) without gadolinium.

Endoscopy and biopsy with/without procedural sedation.

Sigmoidoscopy following water enemas (mainly if UC is suspected).

We opted for MRE as the most appropriate investigation as her clinical picture fitted a more chronic condition. The blood, stool and US result suggested IBD presenting during pregnancy rather than an acute condition, such as infective diarrhoea. However, this investigation does not allow a histological confirmation of presumed IBD. In steroid-resistant suspected IBD, an MRE is recommended by the British Society of Gastroenterology to rule out abscess formation prior to starting biological treatment.3 A colonoscopy with or without sedation in pregnancy would have given the added benefit of a histological diagnosis, while at 27 weeks’ gestation, it carries a small risk of precipitating premature labour.4 In our opinion, an MRE is superior in pregnancy as it is non-invasive and it quantifies mural thickening, mesenteric and extraluminal findings in active, resistant disease.5

Initiation of biological treatment in the third trimester is unusual. At the time of managing the case, medical literature advised stopping biological agents in the third trimester in an attempt to lower their neonatal levels and maintain the active transport of maternal antibodies across the placenta.6,7 More recently, new consensus guidelines do not make this recommendation.8 We opted for infliximab therapy, taking into consideration the delay in response with azathioprine and the severity and timing of her deterioration in relation to her estimated due date. Infliximab crosses the placenta and has been detected up to six months in infants born to mothers who received it antenatally. Apart from the risk of direct infections, there are specific concerns with acute infections from live attenuated vaccines in the first six months of life.9,10

Our case is unique with regard to the severity of presentation with weight loss, oral diet intolerance and requirement of temporary nasogastric feeding during pregnancy. Institution of treatment with a biological agent during the third trimester was considered the most appropriate therapy, and it allowed for disease control and avoidance of complications until after delivery. This is important as active disease poses the highest risk to pregnancy.11 Flares during pregnancy will lead to increased risk of preterm birth, small for gestational age baby, low Apgar scores and stillbirth.12 Our patient responded well to biological treatment while pregnant; however, she became a non-responder postpartum. Usually, pregnancy has a beneficial effect on the risk of postpartum IBD flares. This is probably related to different human leukocyte antigen profiles between mother and baby, as fetal–paternal antigens lead to downregulation of maternal immune response during pregnancy. Further investigation of this relationship might help in the development of new therapies for severe resistant disease.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their gratitude to Bethany Jackson (Anaesthesia Department secretary) for her help in retrieving patient’s notes.

Declaration of conflicting interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical approval

This article was submitted with written patient’s consent.

Guarantor

MM.

Contributorship

All listed authors were involved in the care of the patient and have contributed to drafting the manuscript. MM and MC were involved in revising the manuscript.

References

- 1.NICE Diagnostics Guidance. Focal calprotectin diagnostic tests for inflammatory diseases of the bowel. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/dg11/chapter/6-Considerations (2013).

- 2.Mahadevan U, Martin CF, Sandler RS, et al. PIANO: a 1000 patient prospective registry of pregnancy outcomes in women with IBD exposed to immunomodulators and biologic therapy. Gastroenterology 2012; 142(Suppl 1): S149; Abstract 865–S149; Abstract 865. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mowat C, Cole A, Windsor A, et al. On behalf of the IBD Section of the British Society of Gastroenterology. Guidelines for the management of inflammatory bowel disease in adults. Gut 2011; 60: 571–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Lima A, Galjart B, Wisse PH, et al. Does lower gastrointestinal endoscopy during pregnancy pose a risk for mother and child? A systematic review. BMC Gastroenterol 2015; 15: 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stern MD, Kopylov U, Ben-Horin S, et al. Magnetic resonance enterography in pregnant women with Crohn’s disease: case series and literature review. BMC Gastroenterol 2014; 16: 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gisbert JP. Safety of immunomodulators and biologics for the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease during pregnancy and breast-feeding. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2010; 16: 881–895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peppercorn MA and Mahadevan U. Fertility, pregnancy and nursing in inflammatory bowel disease, www.uptodate.com (accessed 23 June 2016).

- 8.Nguyen GC, Seow CH, et al. On behalf of the IBD in Pregnancy Consensus Group. The Toronto Consensus Statements for the management of inflammatory bowel disease in pregnancy. Gastroenterology 2016; 150: 734–757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kane S. Pregnancy in inflammatory bowel disease. In: Pregnancy in gastroenterological disorders, American College of Gastroenterology, gi.org/wp-content/uploads/…/institute-PregnancyMonograph.pdf (accessed 10 September 2016), pp.66–74.

- 10.Horst S, Kane S. The use of biologic agents in pregnancy and breastfeeding. Gastroenterol Clin N Am 2014; 43: 495–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mahadevan U, Matro R. Care of the Pregnant patient with inflammatory bowel disease. Obstet Gynecol 2015; 126: 401–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bröms G, Granath F, Linder M, et al. Birth outcomes in women with inflammatory bowel disease: effects of disease activity and drug exposure. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2014; 20: 1091–1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]