Abstract

Background: Decontamination of the skin prior to incision is part of the standard of care for any surgical procedure. Previous studies have demonstrated variable efficacy of different surgical preparation solutions based on anatomic location. The purpose of this study is to determine the effectiveness of 3 commonly used surgical preparation solutions in eliminating bacteria from the skin prior to incision for common elective soft tissue hand procedures. Methods: A total of 240 patients undergoing clean, elective, soft tissue hand surgery were prospectively randomized to 1 of 3 groups (ChloraPrep, DuraPrep, or Betadine). Prepreparation and postpreparation cultures were obtained adjacent to the surgical incision and neutralization was performed on the obtained specimen. Cultures were held for 14 days and patients followed for 6 weeks postoperatively. Results: Postpreparation cultures were positive in 21 of 80 (26.3%) ChloraPrep patients, 3 of 79 (3.8%) DuraPrep patients, and 1 of 81 (1.2%) Betadine patients (P < .001). There was no difference in the postpreparation culture rate between DuraPrep and Betadine (P = 1.000). Conclusions: Duraprep and Betadine were found to be superior to Chloraprep for skin decontamination prior to clean elective soft tissue hand surgery. The bacterial flora of the hand was found to be different from those of the shoulder and spine. The clinical significance of this finding requires clinical consideration because the majority of prepreparation and postpreparation positive cultures were of Bacillus species, which are rarely a cause of postoperative infections.

Keywords: preparation solution, Betadine, ChloraPrep, DuraPrep

Introduction

Although the infection rate for hand surgery is low, skin antisepsis prior to incision is a cornerstone of surgical standard of care. The purpose is to reduce bacterial colonization and consequently to reduce the risk of surgical site infection (SSI).12,19,21,28 Postoperative infection in hand surgery leads to poor long-term patient outcomes with significant morbidity, such as stiffness, contractures, and even amputation.2,4,11,16 It also accrues significant health care cost with revision surgeries and postoperative infection control.16,13-15,17 The ideal skin preparation solution would eliminate all bacteria from the skin prior to incision, have effects that last the duration of the surgical procedure, and have a low risk of complications and side effects.

Previous studies have elucidated the common bacterial pathogens in lumbar spine surgery,26 shoulder surgery,24 and foot and ankle surgery.20,23 The bacterial profile was found to differ among these sites, but the most common pathogens included coagulase-negative Staphylococcus and Propionibacterium. On the contrary, the bacterial profile of the human hand has not been well established in the patient even though there have been documented studies examining antisepsis of the surgeon’s hands.18,25 Aiello et al1 found vastly different bacterial flora on the hands of homemakers compared with nurses, suggesting that work environment and frequent antiseptic use in the health care setting have a significant impact on hand flora. Therefore, it is likely that repeated hand washing and exposure to hospital bacteria alters the microbial colonization of the surgeon’s hands and this may not be an appropriate marker for the patient’s hand.1,18,25 Although evidence supports the use of preoperative antisepsis to reduce bacterial colonization and SSI rates,1,3,5,17,19,22,23,27 2 Cochrane reviews of SSI after clean surgeries did not yield differential efficacy of one antiseptic agent over another.6,8

The purpose of this study is to determine the effectiveness of 3 commonly used surgical preparation solutions (ChloraPrep, DuraPrep, and Betadine) in eliminating bacteria from the skin prior to incision. The null hypothesis is that there is no difference between these groups with respect to the rate of positive postpreparation skin culture.

Materials and Methods

This prospective randomized trial was performed according to the CONSORT guidelines. After Institutional Review Board approval was obtained, 240 patients were prospectively enrolled to participate in this study (see Figure 1), from May 2013 to August 2014. All procedures were performed by 1 of 2 hand fellowship-trained surgeons at a single institution. This trial was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (under registry no. NCT01676051). The following inclusion criteria were used: (1) patient undergoing elective clean soft tissue hand surgery (carpal tunnel release, trigger finger, de Quervain release, mass excision or excision ganglion cyst, or other elective clean hand surgeries) and (2) being able to read and understand English. The following exclusion criteria were used: (1) open wound, (2) previous infection in the operative hand or ongoing infection elsewhere in the body, (3) fracture, (4) allergy to any component of the skin preparation solutions, and (5) hardware implantation. Per institution protocol, all patients in this series received antibiotic prophylaxis within 60 minutes prior to skin incision and before tourniquet inflation, using cefazolin 1 g or 2 g, or in the cases of penicillin allergy, 600 mg of clindamycin was given. Patients were monitored for signs of postoperative wound infection for a minimum of 6 weeks after surgery.

Figure 1.

CONSORT flow diagram.

Skin Preparation

Patients were randomized immediately prior to skin preparation, by opening a sealed and opaque envelope (240 envelopes were created prior to study initiation and then drawn at random by the surgeon), to 1 of 3 commonly used surgical preparation solutions: Betadine solution (10% povidone-iodine; Purdue Pharma LLP, Stamford, Connecticut), ChloraPrep (2% chlorhexidine gluconate and 70% isopropyl alcohol; Enturia, El Paso, Texas), or DuraPrep (0.7% available iodine and 74% isopropyl alcohol; 3MHealthcare, St. Paul, Minnesota). The surgical extremity was then prepared according to the manufacturer’s instructions by the attending surgeon or resident. Each preparation solution was allowed to completely dry. The study aimed for 80 patients in each group, and randomization resulted in 80, 79, and 81 patients among the 3 groups, respectively.

Culture Analysis and Neutralization

Aerobic and anaerobic cultures were taken over a 1-cm area of skin within 1 cm of the planned incision site prior to skin antisepsis and immediately after the preparation solution had dried. Specimens were obtained using a premoistened, sterile culture swab (BBL Culture Swab Plus; Becton, Dickinson, and Co, Franklin Lakes, New Jersey). A validated neutralization agent (Microbiotest; Sterling, Virginia) was applied to the swab immediately after the specimen was obtained to neutralize the preparation in the specimen. Without a neutralization agent, the active preparation solution would be transferred to the petri dish and prevent bacteria from growing, thereby hindering accurate profiling of the bacterial flora of the hand. The neutralization solutions were previously described by Savage et al.26 The same neutralization solution was used for both Betadine and DuraPrep. Specimens were transported immediately to the microbiology lab and cultures were held for 14 days. The primary outcome in this study was the presence of a postpreparation positive culture at 14 days. Secondary outcomes included the presence of a positive prepreparation positive culture within 14 days and presence of postoperative infection within 6 weeks of surgery. All patients were followed for 6 weeks postoperatively to document any evidence of postoperative infection, defined as need for antibiotics or surgical intervention.

Statistical Analysis

Sample size calculations were based on data from prospective randomized trials of shoulder and lumbar spine preparation efficacy.24,26 A clinically significant difference in colonization rates was set at 20%, with 80% power and α = 0.05. The a priori power analysis found that 80 patients per surgical preparation group would be needed. The Kruskal-Wallis test or pairwise Mann-Whitney U test, and chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test were used to compare demographic data and culture data between the 3 skin preparation solutions. Bonferroni correction was applied to post hoc tests between pairs of solutions. Significance for all calculations was set at P < .05. All statistical analyses were performed with the cooperation of institutional biostatisticians using SPSS 20 (IBM, Armonk, New York).

Results

In all, 240 patients, with an average age of 54 years (range 14-93), participated in this prospective randomized trial from May 2013 to August 2014. Please refer to Table 1 for a comparison of demographic data between groups. There was also no difference in the Charleson Comorbidity Index (CCI) unadjusted (P = .416) and adjusted (P = .354) between groups. Please refer to Table 2 for a breakdown by procedure for each preparation solution.

Table 1.

Comparison of Demographic Data Between Groups.

| ChloraPrep | DuraPrep | Betadine | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age (SD) | 53 (14) | 56 (7) | 53 (14) | .27 |

| Mean BMI (SD) | 30.5 (7.8) | 30.6 (8.6) | 31.1 (8.0) | .73 |

| Male:female ratio | 22:58 | 23:56 | 31:50:00 | .29 |

Note. BMI = body mass index.

Table 2.

Breakdown by Procedure.

| Procedure | ChloraPrep | DuraPrep | Betadine |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carpal Tunnel Release | 46 | 43 | 56 |

| Trigger Release | 13 | 14 | 13 |

| De Quervain | 3 | 4 | 3 |

| Excision mass | 14 | 15 | 9 |

| Other | 5 | 3 | 0 |

| Total | 81 | 79 | 81 |

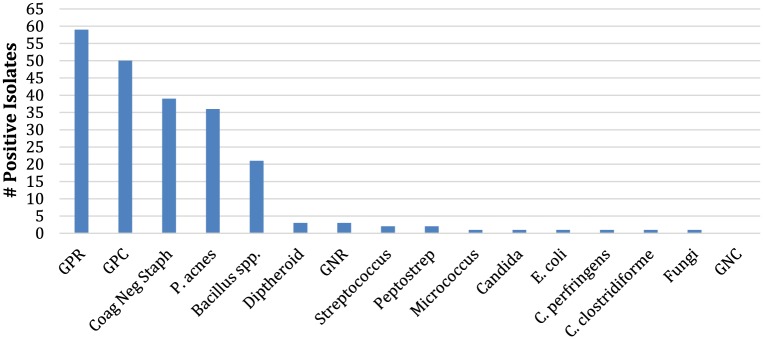

Prepreparation cultures were positive in 91 of 240 (37.9%) patients, and postpreparation cultures were positive in 25 of 240 (10.4%) patients. Prepreparation cultures (Figure 2) were positive in 32 of 80 (40.0%) ChloraPrep patients, 24 of 79 (30.4%) DuraPrep patients, and 35 of 81 (43.2%) Betadine patients (P = .200). Figure 2 contains categories such GPC (gram positive cocci) that includes coagulase-negative Staphylococcus and Streptococcus; these clinically relevant or prevalent organisms were then also listed separately. Subtype analysis of each bacterium found prepreparation Bacillus species to be present in 13 of 80 (16.3%) ChloraPrep, 6 of 79 (7.6%) DuraPrep, and 2 of 81 (2.5%) Betadine patients (P = .008). There was no difference in the rates of coagulase-negative Staphylococcus and Propionibacterium acnes among the solution groups, P = .198 and P = .222, respectively.

Figure 2.

Prepreparation bacterial isolates.

Note. GPR = gram-positive rods; GPC = gram-positive cocci; GNR = gram-negative rods; GNC = gram-negative cocci.

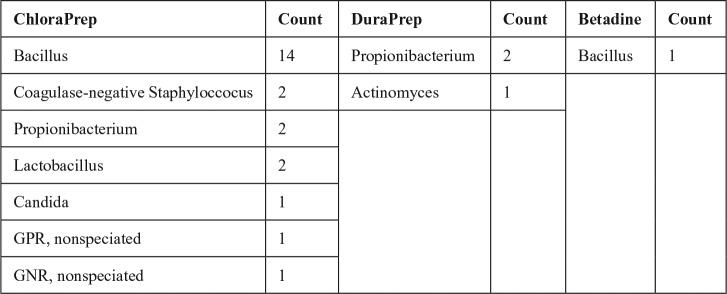

Postpreparation cultures were positive in 21 of 80 (26.3%) ChloraPrep, 3 of 79 (3.8%) DuraPrep, and 1 of 81 (1.2%) Betadine patients (P < .001). There was no difference in postpreparation culture rates between DuraPrep and Betadine (P = 1.000); however, there were differences between ChloraPrep and DuraPrep (P < .001) and ChloraPrep and Betadine (P < .001). Postpreparation bacterial subtype analysis found Bacillus to be present in 14 of 80 (17.5%) ChloraPrep, 0 of 79 (0%) DuraPrep, and 1 of 81 (1.2%) Betadine patients (P < .001). As some culture-positive patients may become culture negative (depending on the activity of the prep solution) and patients may also retain their original culture status, the prepreparation and postpreparation bacterial count may not add up directly (ie, ChloraPrep group had 13 Bacillus prepreparation, but 14 Bacillus postpreparation count). Full details of the postpreparation culture positivity are presented in Figure 3. As there were 2 patients who had Bacillus as well as another organism, the total microbial count was greater than the total number of subjects who were culture positive.

Figure 3.

Postpreparation microbial culture breakdown.

Note. GPR = gram-positive rods; GNR = gram-negative rods.

ChloraPrep resulted in an absolute decrease of 14% and relative decrease of 34% in positive cultures. DuraPrep resulted in an absolute decrease of 27% and a relative decrease of 88% in positive cultures. Betadine resulted in an absolute decrease of 42% and a relative decrease of 97% in positive cultures.

As Bacillus was the sole organism to have statistical significance in both prepreparation and postpreparation analysis of the colonization rate, an analysis was performed with the Bacillus excluded. This resulted in 80 of 240 (33%) positive prepreparation cultures with no differences among the three preparation solutions (P = .07). It is important to note that after Bacillus exclusion, 10 of the 21 subjects were retained in analysis due to culture positivity from at least one other bacteria, as many subjects had polymicrobial cultures; therefore, the number of Bacillus cultures excluded did not exactly equal the number of subjects excluded. Postpreparation cultures were positive in 11 of 240 (4.6%) patients (with 14 of 25 patients excluded because they were only positive for Bacillus) and remained different among the 3 groups, P = .005. DuraPrep had 3 of 79 (3.8%) postpreparation positive cultures compared with 0 of 81 (0%) postpreparation positive cultures in the Betadine group (P = .4). ChloraPrep had 8 of 80 (10%) postpreparation positive cultures and remained significantly greater than Betadine (P = .009). However, comparison of postpreparation ChloraPrep and DuraPrep lost statistical significance (P = .4) after the exclusion of Bacillus, in 8 of 80 (10%) and 3 of 79 (3.8%) cultures, respectively.

The most common bacteria cultured prepreparation were coagulase-negative Staphylococcus (39), P. acnes (36), and Bacillus species (21). The most common bacteria culture postpreparation were Bacillus species (15), P. acnes (4), and coagulase-negative Staphylococcus (2). Four patients had a postoperative SSI: 2 from ChloraPrep, 1 from DuraPrep, and 1 from Betadine (P = .8). These 4 infections were deemed superficial by the treating surgeon and treated successfully with oral antibiotics. No cultures were taken per the standard practice of the treating surgeons.

Secondary analyses of comorbidities and social history found that gender, age, body mass index, diabetes mellitus, and connective tissue disease did not correlate significantly with colonization rates overall or with Staphylococcus, Propionibacterium, or Bacillus separately.

Discussion

In this prospective randomized trial, Betadine and DuraPrep were found to be more effective than ChloraPrep for the elimination of bacteria from the skin prior to incision in elective clean hand surgeries. The clinical significance of this finding requires consideration because the majority of prepreparation and postpreparation positive cultures were of Bacillus species, which are rarely a cause of postoperative infections.10 Furthermore, the bacterial flora of the hand was found to be different from those of other orthopedic sites, including the shoulder. Bacillus is a common bacterium found in normal human gut flora, which may explain its higher prevalence on hands compared with shoulders or lumbar spine as the hands are used for perineal hygiene.

Consideration should be given to the use of Betadine as the primary preoperative antiseptic solution as it is effective in eliminating bacteria from the hand (1.3% postpreparation positive cultures decreased from 56.3% prepreparation), is inexpensive, and does not contain alcohol (thus eliminating the concern for surgical fires related to the use of preparation solutions containing alcohol). However, Betadine has been known to cause itching and skin irritation if not removed from the skin after surgery.7,17

The rate of positive prepreparation cultures (37.9%) was surprisingly low in our study. In comparison, Savage et al26 found 82% positive prepreparation cultures for spine surgery and Saltzman et al24 found 70% to 95% positive prepreparation cultures depending on the site about the shoulder. The reason for the low rate of positive prepreparation cultures is unclear. It could be related to the use of antimicrobial soap and frequent hand washing found in many patients. Unlike spine and shoulder surgery, patients may wash their hands multiple times prior to surgery, often only minutes before being taken back to the operating room. It is possible that the antimicrobial effect of the hand soap decreased overall bacterial colonization. Standard hand soaps in our hospital bathrooms contain chlorhexidine, which can be found on the hands of health care professionals several days after the last scrub.9 This may explain the much lower rates of culture in the DuraPrep and Betadine groups, as these patients would have already had their hands washed first with chlorhexidine after using the bathroom and then with the povidone-iodine–based solutions in the operating room, increasing microbial coverage and inadvertently improving antisepsis efficacy. Although suboptimal for direct comparisons of preparation solution efficacy, it does mirror a real-world situation. Roukis23 performed a literature review and suggested chlorhexidine scrub with isopropyl alcohol followed by povidone-iodine might have the best antisepsis efficacy.

The rate of SSI in elective clean hand surgery is low; the rate of SSI in our study is 1.7%. This study was not powered to demonstrate a direct correlation between SSI and type of preparation solution due to the inherently low rate of SSI in clean elective hand surgeries. However, as previous studies showed that effective surgical preparation solutions reduced SSI, it is intuitive that this applies to clean elective hand surgeries. There has been no previous study demonstrating the differential efficacy among the 3 surgical preparation solutions in the elective hand surgeries.

One limitation of the study was that we powered our sample size to distinguish a 20% or greater difference in the rate of postpreparation colonization. The colonization rate was significantly higher in the ChloraPrep group compared with either Betadine or DuraPrep. However, we did not find a significant difference of at least 20% between Betadine and DuraPrep; we would need a larger study to detect the smaller difference in efficacy, if one exists, between the 2 solutions. A second limitation is that our study was not powered to detect a difference between SSI rates among the 3 solution groups. As SSI rates in clean elective hand surgery are so low, a much larger sample size would be necessary to detect such a difference. Another limitation is that despite randomization, our prepreparation cultures found a significant difference in Bacillus cultures rates, prior to the use of surgical solutions, among the 3 solution groups and the reason for this is uncertain. This may be an effect resulting from probability. Notably, our secondary analysis with the exclusion of Bacillus still showed that Betadine and DuraPrep remained significantly more efficacious than ChloraPrep in the decolonization of the surgical site on the hand. We are unable to comment on the duration of antiseptic activity of the preparation solutions as we did not take cultures after closure. We felt that the short duration of the procedures in this study did not warrant postclosure cultures. Finally, the surgeon was not blinded to the type of preparation solution used. However, the microbiology lab was blinded to the type of preparation solution and this should therefore not bias our results.

Footnotes

Authors’ Note: There was no agreement with any sponsor of the research that prevents the authors from publishing both positive and negative results or forbids the authors from publishing this research without the prior approval of the sponsor.

Ethical Approval: This study was approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board.

Statement of Human and Animal Rights: All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.

Statement of Informed Consent: Informed consent was obtained from all patients enrolled in this study.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Funding for this study was via internal funding by the University of Pittsburgh Department of Orthopaedics, a grant from the Pittsburgh Foundation, and a National Institutes of Health grant (UL1-TR-000005).

References

- 1. Aiello AE, Cimiotti J, Della-Latta P, Larson EL. A comparison of the bacteria found on the hands of “homemakers” and neonatal intensive care unit nurses. J Hosp Infect. 2003;54(4):310-315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Astagneau P, Rioux C, Golliot F, Brucker G, INCISO Network Study Group. Morbidity and mortality associated with surgical site infections: results from the 1997-1999 INCISO surveillance. J Hosp Infect. 2001;48(4):267-274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bhavan KP, Warren DK. Surgical preparation solutions and preoperative skin disinfection. J Hand Surg Am. 2009;34(5):940-941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bykowski MR, Sivak WN, Cray J, Buterbaugh G, Imbriglia JE, Lee WP. Assessing the impact of antibiotic prophylaxis in outpatient elective hand surgery: a single-center, retrospective review of 8,850 cases. J Hand Surg Am. 2011;36(11):1741-1747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Darouiche RO, Wall MJ, Jr, Itani KM, Otterson MF, Webb AL, Carrick MM, et al. Chlorhexidine-alcohol versus povidone-iodine for surgical-site antisepsis. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(1):18-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dumville JC, McFarlane E, Edwards P, Lipp A, Holmes A. Preoperative skin antiseptics for preventing surgical wound infections after clean surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(3):CD003949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Eardley WG, Watts SA, Clasper JC. Limb wounding and antisepsis: iodine and chlorhexidine in the early management of extremity injury. Int J Low Extrem Wounds. 2012;11(3):213-223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Edwards PS, Lipp A, Holmes A. Preoperative skin antiseptics for preventing surgical wound infections after clean surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;(3):CD003949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Faoagali J, Fong J, George N, Mahoney P, O’Rourke V. Comparison of the immediate, residual, and cumulative antibacterial effects of Novaderm R,* Novascrub R,* Betadine Surgical Scrub, Hibiclens, and liquid soap. Am J Infect Control. 1995;23(6):337-343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fowler JR, Ilyas AM. Epidemiology of adult acute hand infections at an urban medical center. J Hand Surg Am. 2013;38(6):1189-1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Glass KD. Factors related to the resolution of treated hand infections. J Hand Surg Am. 1982;7(4):388-394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Harrop JS, Styliaras JC, Ooi YC, Radcliff KE, Vaccaro AR, Wu C. Contributing factors to surgical site infections. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2012;20(2):94-101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Johnson AJ, Daley JA, Zywiel MG, Delanois RE, Mont MA. Preoperative chlorhexidine preparation and the incidence of surgical site infections after hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2010;25(6)(suppl):98-102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kapadia BH, Johnson AJ, Daley JA, Issa K, Mont MA. Pre-admission cutaneous chlorhexidine preparation reduces surgical site infections in total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2013;28(3):490-493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kapadia BH, Johnson AJ, Issa K, Mont MA. Economic evaluation of chlorhexidine cloths on healthcare costs due to surgical site infections following total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2013;28(7):1061-1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kirkland KB, Briggs JP, Trivette SL, Wilkinson WE, Sexton DJ. The impact of surgical-site infections in the 1990s: attributable mortality, excess length of hospitalization, and extra costs. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1999;20(11):725-730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lee I, Agarwal RK, Lee BY, Fishman NO, Umscheid CA. Systematic review and cost analysis comparing use of chlorhexidine with use of iodine for preoperative skin antisepsis to prevent surgical site infection. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2010;31(12):1219-1229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Merollini KM, Zheng H, Graves N. Most relevant strategies for preventing surgical site infection after total hip arthroplasty: guideline recommendations and expert opinion. Am J Infect Control. 2013;41(3):221-226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Noorani A, Rabey N, Walsh SR, Davies RJ. Systematic review and meta-analysis of preoperative antisepsis with chlorhexidine versus povidone-iodine in clean-contaminated surgery. Br J Surg. 2010;97(11):1614-1620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ostrander RV, Botte MJ, Brage ME. Efficacy of surgical preparation solutions in foot and ankle surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87(5):980-985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Parienti JJ, Thibon P, Heller R, Le Roux Y, von Theobald P, Bensadoun H, et al. Hand-rubbing with an aqueous alcoholic solution vs traditional surgical hand-scrubbing and 30-day surgical site infection rates: a randomized equivalence study. JAMA. 2002;288(6):722-727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Roberts AH, Roberts FE, Hall RI, Thomas IH. A prospective trial of prophylactic povidone iodine in lacerations of the hand. J Hand Surg Br. 1985;10(3):370-374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Roukis TS. Bacterial skin contamination before and after surgical preparation of the foot, ankle, and lower leg in patients with diabetes and intact skin versus patients with diabetes and ulceration: a prospective controlled therapeutic study. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2010;49(4):348-356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Saltzman MD, Nuber GW, Gryzlo SM, Marecek GS, Koh JL. Efficacy of surgical preparation solutions in shoulder surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91(8):1949-1953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Salvi M, Chelo C, Caputo F, Conte M, Fontana C, Peddis G, et al. Are surgical scrubbing and pre-operative disinfection of the skin in orthopaedic surgery reliable? Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2006;14(1):27-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Savage JW, Weatherford BM, Sugrue PA, Nolden MT, Liu JC, Song JK, et al. Efficacy of surgical preparation solutions in lumbar spine surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(6):490-494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Swenson BR, Hedrick TL, Metzger R, Bonatti H, Pruett TL, Sawyer RG. Effects of preoperative skin preparation on postoperative wound infection rates: a prospective study of 3 skin preparation protocols. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2009;30(10):964-971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Tanner J, Swarbrook S, Stuart J. Surgical hand antisepsis to reduce surgical site infection. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(1):CD004288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]