Abstract

Background: The purpose of this study was to look for differences in mechanism, radiographic findings, and treatment between mallet fractures of the thumb and mallet fractures of the index through small fingers. Methods: This retrospective study included 24 mallet fractures of the thumb and 392 mallet fractures of other digits. We compared demographics, injury factors (side, dominant hand, time between injury and first visit, and injury mechanism), subluxation, fragment size, treatment, and time from injury to final evaluation between the 2 groups. Results: Mallet fractures of the thumb presented for treatment sooner after injury (2.9 vs 13 days on average), had less fragment displacement (27% vs 33%), and less articular involvement (39% vs 46% on average). None of the mallet fractures of the thumb had radiographic evidence of subluxation, whereas 25% of mallet fractures of other fingers had initial or later subluxation. Conclusions: Mallet fractures of the thumb are not likely to subluxate.

Keywords: thumb, mallet fracture, interphalangeal joint

Introduction

A mallet injury is an extensor tendon injury of the distal interphalangeal (DIP) joint of the finger or the interphalangeal (IP) joint of the finger or thumb. The tendon insertion detaches with or without an associated avulsion fracture of the distal phalanx (mallet fracture or bony mallet deformity). Mallet thumb, avulsion of the extensor pollicis longus tendon from its distal phalangeal insertion, is less common than mallet finger.3,14 There are few reports about mallet thumbs, particularly those with associated fracture.3,9,14

Little is known about the difference between mallet fractures of the thumb compared with mallet fractures of the index through small fingers with respect to etiology, radiographic findings, and treatment. They are seemingly less common, perhaps due to shorter length and greater size of the thumb. We tested the null hypothesis that, compared with mallet fracture of the index through small fingers, mallet fractures of the thumb have similar demographic, injury, radiographic, and treatment characteristics.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

After institutional review board approval, the radiographs and medical records of all adult patients with a mallet fracture treated by 11 hand specialists at 3 urban hospitals between January 2004 and December 2014 were reviewed. We started at 2004 because digital images were not available from prior years.

Patients

International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Edition (ICD-9) codes (736.1, 816.02, 816.03, and 816.0) within the defined time frame were used to identify all patients with potential mallet fractures in our institutional database (N = 16 258). To identify mallet fractures, we excluded all radiologic and operation reports without at least one of the following words: “fracture,” “distal phalanx,” “terminal phalanx,” “base,” “intra-articular,” “avulsion,” “finger,” “DIP,” “distal interphalangeal joint,” and “mallet fracture” with text searching using STATA 13.0 statistic software (StataCorp LP, College Station, Texas; n = 5950). We also excluded patients younger than 18 years of age, and Doyle type IVa fractures (n = 2512).4 The remaining patients’ radiographs and medical records (n = 7796) were reviewed by researchers to confirm the diagnosis of a mallet fracture and to distinguish mallet fractures of the thumb from mallet fractures of the index through small fingers. Mallet fractures of the thumb were defined as an avulsion fracture of the extensor pollicis longus tendon insertion onto the distal phalanx and an extensor lag on examination.

We identified 416 mallet fractures: 24 mallet fractures of the thumb (6% of all mallet fractures) and 392 mallet fractures of other digits (Tables 1, 2, and 3). Three researchers (2 of them physicians) confirmed the diagnosis through review of the electronic records. In addition, 3 hand surgeons independently confirmed that the identified injuries of the thumb were indeed mallet fractures by reviewing anonymized radiographs.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics (n = 24).

| Mean (SD) | Range | |

|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 46 (15) | 18-72 |

| Follow-up (days; n = 16) | 50 (40) | 6-161 |

| Days to treatment | 2.9 (4.7) | 0-20 |

| Articular involvement, % | 39 (16) | 10-69 |

| Fragment displacement, % | 26 (25) | 0-89 |

| Number (%) | ||

| Sex | ||

| Male | 14 (58) | |

| Female | 10 (41) | |

| Fracture type | ||

| Open | 1 (4.2) | |

| Close | 23 (96) | |

| Subluxation | ||

| Yes | 0 (0) | |

| No | 24 (100) | |

| Comminuted fractures | ||

| Yes | 2 (8.3) | |

| No | 22 (92) | |

| Type of treatment | ||

| Cast | 4 (17) | |

| Splint | 12 (50) | |

| Unknown | 2 (8.3) | |

| Kirschner wire | 3 (13) | |

| Screw | 2 (8.3) | |

| Suture | 1 (4.2) | |

| Complication | ||

| Yes | 1 (4.2) | |

| No | 20 (83) | |

| Unknown | 3 (13) | |

| Affected hand side | ||

| Right | 15 (63) | |

| Left | 9 (37) | |

| Dominant hand | ||

| Right | 14 (58) | |

| Left | 4 (17) | |

| Unknown | 6 (25) | |

Note. SD = standard deviation.

Table 2.

Clinical Results (n = 24).

| Patient | Sex | Age | Mechanism | Affected side | Dominant hand | Comorbidities | Subluxation | Type of treatment | Immobilization |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Male | 59 | Cut with table saw | Left | Right | Daily alcohol | No | Kirschner wire | 2-wk spica, 4-wk short splint |

| 2 | Male | 18 | Sport: tennis | Left | Right | — | No | Cast | 4-wk splint, 4-wk night splint |

| 3 | Male | 58 | Fall | Right | Unknown | — | No | Splint | |

| 4 | Male | 57 | Fall | Right | Right | Smoking | No | Suture | |

| 5 | Male | 55 | Injury; playing with his son | Left | Right | Smoking, obesity | No | Cast | 6-wk cast, 6-wk night splint |

| 6 | Female | 40 | Left | Left | Smoking, obesity | No | Kirschner wire | ||

| 7a | Female | 60 | Fall from stairs | Right | Right | Daily alcohol | No | Splint | 6-wk splint |

| 8 | Male | 30 | Fall from bike | Left | Unknown | — | No | Screw | Spica cast |

| 9 | Male | 32 | Sport: flag football | Left | Right | — | No | Splint | 5-wk splint |

| 10 | Male | 31 | Sport: basketball | Right | Unknown | Obesity | No | Screw | 4-wk splint |

| 11 | Female | 21 | Fall in bathroom | Right | Unknown | Obesity | No | Splint | |

| 12a | Female | 60 | Catching a heavy bottle | Left | Right | Smoking, obesity | No | Splint | |

| 13 | Male | 61 | Box fell on thumb | Right | Right | Smoking | No | Splint | |

| 14 | Male | 47 | Sport: basketball | Right | Right | — | No | Splint | 5-wk splint, 4-wk night splint |

| 15 | Female | 72 | Fall on shoulder and hand | Right | Unknown | — | No | Unknown | |

| 16 | Female | 56 | Right | Unknown | — | No | Unknown | ||

| 17 | Female | 49 | Suicide attempt | Right | Left | History of alcohol dependence | No | Splint | |

| 18 | Male | 22 | Fall from stairs | Left | Left | — | No | Splint | 6-wk splint |

| 19a | Male | 50 | Sport: ice hockey | Right | Right | — | No | Splint | 4-wk splint, 4-wk night splint |

| 20 | Male | 35 | Jammed thumb | Right | Right | Splint | No | Kirschner wire | 4-wk spica splint |

| 21 | Female | 54 | Right | Right | — | No | Splint | Opponens splint | |

| 22 | Female | 55 | Sport: tennis | Right | Right | Smoking, daily alcohol | No | Splint | Opponens splint |

| 23 | Female | 52 | Sport: football | Right | Right | — | No | Cast | 4-wk cast, 2-4 wk splint |

| 24 | Male | 26 | Sport: basketball | Left | Left | — | No | Cast | 4-wk cast, 2-4 wk splint |

Comminuted fracture.

Table 3.

Clinical Results (n = 24).

| Patient | Wound? | Adverse event | Days to treatment | Articular involvement (%) | Fragment displacement (%) | Follow-up (d) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Yes | No | 0 | 52 | 37 | 53 |

| 2 | Closed | No | 0 | 50 | 21 | 37 |

| 3 | Closed | No | 0 | 45 | 34 | |

| 4 | Closed | No | 7 | 45 | 17 | |

| 5 | Closed | No | 2 | 23 | 89 | 44 |

| 6 | Closed | No | 20 | 45 | 46 | 21 |

| 7a | Closed | No | 1 | 32 | 12 | 22 |

| 8 | Closed | No | 5 | 58 | 27 | |

| 9 | Closed | No | 8 | 52 | 64 | 35 |

| 10 | Closed | Prominent hardware | 0 | 37 | 41 | 35 |

| 11 | Closed | No | 0 | 39 | 5 | |

| 12a | Closed | No | 0 | 47 | 2 | |

| 13 | Closed | No | 10 | 15 | 4 | 161 |

| 14 | Closed | No | 3 | 69 | 86 | 100 |

| 15 | Closed | No | 0 | 10 | 36 | |

| 16 | Closed | 1 | 36 | 0 | ||

| 17 | Closed | 0 | 15 | 3 | ||

| 18 | Closed | No | 1 | 27 | 8 | 19 |

| 19a | Closed | No | 0 | 58 | 22 | 6 |

| 20 | Closed | No | 0 | 28 | 15 | 64 |

| 21 | Closed | No | 0 | 31 | 7 | 12 |

| 22 | Closed | 6 | 14 | 11 | 34 | |

| 23 | Closed | No | 4 | 57 | 44 | 87 |

| 24 | Closed | No | 1 | 41 | 5 | 68 |

Comminuted fracture.

Demographic and clinical data were gathered including gender, age at the time of initial visit, affected side, dominant hand, period between injury and first visit, injury mechanism (sports injury vs other trauma), fracture type (open vs closed), treatment, and duration of follow-up.

Measurement

Subluxation of the IP joint of the thumb or the index through small fingers was measured on radiographs. The first lateral radiograph performed after trauma was used for the index measurement of the initial fracture, fracture displacement, or subluxation. Late subluxation was defined as subluxation occurring in a later radiograph when the initial radiograph demonstrated a congruent joint. In the case of a secondary subluxation, the first radiograph identifying the presence of subluxation was used for measurements.

With regard to treatment of the subluxated mallet fractures of the fingers, 61% were treated nonoperatively (with 6 weeks of splint or cast immobilization) and 36% were treated using a Kirschner wire, whereas nonsubluxated mallet fractures of the fingers were treated nonoperatively in most cases (92%).

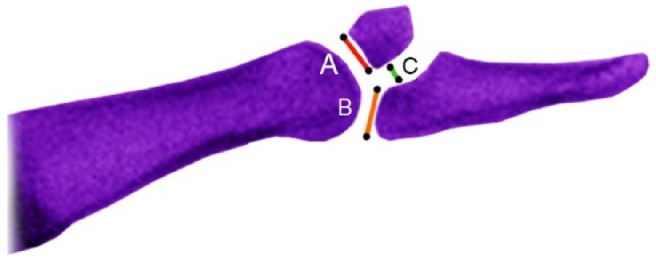

Fragment size was defined as the ratio between articular segment of fractured fragment and the total articular surface in lateral views of the radiograph (Figure 1: articular involvement (%) = A / (A + B) × 100).14 Fragment displacement was defined as the ratio between the amount of fracture fragment displacement compared with the dorsal cortex and the total articular surface in the lateral view. We excluded osteophytes from the calculations by measuring the articular surface alone (Figure 1C). Our cohort consisted of 4 cases in the Doyle type I group (fracture fragment <20% of articular surface), 14 cases in the Doyle type IVb group (fracture fragment involving 20%-50% of articular surface), and 6 cases in the Doyle type IVc group (fracture fragment >50% of articular surface).

Figure 1.

An illustration showing the lines to measure articular involvement and fragment displacement in mallet fractures of the thumb. A, The length of the fracture fragment at the articular surface of the distal phalanx. B, The length of the intact bone segment at the articular surface of the distal phalanx. C, The amount of displacement of fracture fragment.

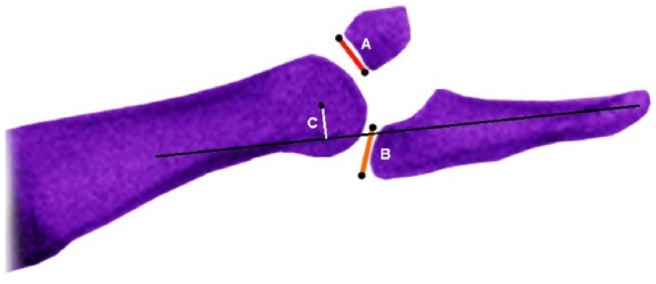

Our method of determining subluxation was similar to Kim and Kim,5 who described a method of measurement for mallet fractures of the fingers on a lateral view. Longitudinal, midaxial lines were made to pass the center of the distal phalanx, and the center of proximal phalanx head was marked (the center of rotation of the IP joint). The IP joint is considered subluxated when the distance between the longitudinal line and the center of middle phalanx head (C) is more than 7% of length of distal phalangeal articular surface (A + B; Figure 2). The duration between injury and treatment was defined as the date of injury to the time of first treatment by a hand surgeon. If the subluxation was not seen on the initial radiographs, but was present on later radiographs, the subluxation was considered secondary. Radiographs were obtained at surgeon discretion, and no protocols were used. The same measurements were made on the mallet fractures of other fingers in a separate study. These results were compared with the mallet fractures of the thumb (Table 4).

Figure 2.

Subluxation of distal interphalangeal (DIP) joint was determined in the lateral view of the injured finger. The DIP was considered to be subluxated when the distance between the longitudinal line and the center of middle phalanx head (C) is more than 7% of length of distal phalangeal articular surface (A + B).

Table 4.

Bivariate Analysis (n = 416).

| Thumbs |

Fingers |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 24 (5.8%) |

n = 392 (94%) |

||

| Mean (SD, 95% CI) | Mean (SD, 95% CI) | ||

| Age, y | 46 (15, 39-52) | 43 (16, 41-44) | .22 |

| Days to treatment | 2.9 (4.7, 0.89-4.9) | 13 (17, 11-14) | <.001 |

| Days to follow-up | 50 (40, 29-71) | 65 (76, 56-74) | .70 |

| Gap ratio (%) | 27 (25, 16-37) | 33 (21, 31-35) | .037 |

| Articular engagement (%) | 39 (16, 32-45) | 46 (14, 45-48) | .037 |

| n (%) | n (%) | P value | |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 14 (58) | 225 (57) | .99 |

| Female | 10 (41) | 167 (43) | |

| Comminution | |||

| Yes | 2 (8.3) | 23 (5.9) | .65 |

| No | 22 (92) | 369 (94) | |

| Subluxation | |||

| Yes | 0 (0) | 97 (25) | .001 |

| No | 24 (100) | 295 (75) | |

| Affected side | |||

| Right | 15 (63) | 209 (53) | .41 |

| Left | 9 (37) | 183 (47) | |

| Dominant hand (na = 267) | |||

| Right | 14 (78) | 223 (90) | .13 |

| Left | 4 (22) | 26 (10) | |

Note. CI = confidence interval.

Exclusion if dominance of hand side was unknown.

Analysis

The mean and standard deviation for continuous variables were calculated and number and percentage for categorical variables. In bivariate analysis, the Fisher test was used because many of the cells in the contingency table had fewer than 5 events. Data were nonparametric due to a small sample size (n = 24), so the Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used for continuous variables. A P value of less than .05 was deemed statistically significant.

Results

In bivariate analysis, mallet fractures of the thumb presented for treatment sooner after injury (2.9 vs 13 days, P < .001), had less fragment displacement (smaller gap ratio; 27% vs 33%, P = .037), and had less articular involvement (39% vs 46%, P = .037; Table 4). According to the Kim and Kim5 classification, none of the mallet fractures of the thumb had radiographic evidence of subluxation, whereas 25% of mallet fractures of other fingers had initial or later subluxation (P = .001; Table 4).

Discussion

Little has been written about mallet fractures of the thumb.3,9,14 In this study, we compared mallet fractures of the thumb with mallet fractures of other fingers and found that mallet fractures of the thumb generally present for treatment earlier and are not associated with subluxation.

The results should be interpreted in light of the strengths and limitations of the study. As with any database study, the validity depends on coding accuracy. However, as the codes are fairly inclusive and all patients were verified by reviewing the medical record including radiographs, we believe that we captured all such patients. Radiographs were not precisely standardized, and some sets of radiographs did not include a perfect lateral view. In this setting, the best possible view was utilized to evaluate subluxation and make fracture measurements. There were no standard protocols for the management of mallet injuries, and treatment and evaluation varied based on surgeon and patient preferences. One patient had only 6-day evaluation in the medical record and might have subluxated later although we feel this is unlikely. Due to strict institutional review board restrictions limiting our ability to contact patients and limited evaluation in the medical record, we do not have data on final motion, function, or satisfaction. One can infer that with no subluxation, there was likely an adaptable loss of thumb hyperextension, and no arthritis or other issues.

There were no differences in patient demographics between the mallet fractures of the thumb compared with other digits. For unclear reasons, patients in this study were somewhat older and more equally distributed in sex than in prior studies.7,12

It is not clear why mallet fractures of the thumb presented to medical attention earlier on average than other mallet fractures. The injury might be more unsettling, perhaps due to the relative importance of the thumb to hand function and the fact that the extensor lag is more noticeable because the IP joint can usually hyperextend.

Most prior studies of mallet thumb address soft tissue mallets.1,2,7,8,10-13 Din and Meggitt3 advocated operative treatment for all mallet thumbs, whereas other authors have advocated closed treatment except in cases where there is an open wound. Patel et al,11 Miura et al,8 Primiano,12 and McCarten et al7 advocated surgery for patients who present more than 4 weeks after injury.6 Tabbal et al13 recommended operative treatment in closed mallet thumb injuries where the extensor pollicis longus tendon retracts proximal to the IP joint, using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

About a half of the patients with a mallet thumb injury described in prior studies had operative treatment.9 In our study, 25% of the patients had an operative treatment. One patient had an open wound. There were no cases of delayed presentation.6 Surgery did not seem to be related to the articular involvement of the fracture fragment.

Our finding of a smaller percentage of fragment displacement and articular involvement, and no subluxation among mallet fractures of the thumb compared with other digits, may help guide the management of these injuries. The lesser articular involvement of mallet fractures of the thumb compared with other digits might relate to the bigger size of the IP joint of the thumb. Greater extensor strength of the extensor pollicis longus compared with the terminal extensor tendon, differences in the tendon attachments, and tighter capsule may make the IP joint of the thumb more stable and limit subluxation. This might also explain the smaller percentage of fragment displacement. Given that Kim and Kim5 found that delay in presentation was a risk factor for subluxation of mallet fractures of the index through small fingers, it is possible but unlikely that the relatively early presentation of patients with mallet fractures of the thumb reduced the risk of subluxation.

Given that mallet fractures of the thumb present to medical attention sooner, but have smaller fragment displacement, less articular involvement, and minimal risk of subluxation compared with mallet fractures of the other digits, the role of surgery is unclear. Mallet injuries of the thumb—mallet fractures in particular—are so uncommon, that futures studies treatment would benefit from collaboration between many centers.

Footnotes

Ethical Approval: This study was approved by our institutional review board.

Statement of Human and Animal Rights: All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.

Statement of Informed Consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1. Aerts BS, Somford MP, Beumer A. Mallet thumb: report of a case. OA Case Reports. 2013;2(16):156. [Google Scholar]

- 2. De Smet L, Van Ransbeeck H. Mallet thumb. Acta Orthop Belg. 2003;69(1):77-78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Din KM, Meggitt BF. Mallet thumb. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1983;65(5):606-607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Doyle J. Extensor tendons: acute injuries. In: Green DP, Hotchkiss RV, Pederson WC, eds. Green’s Operative Hand Surgery. 4th ed. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1999:38. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kim JK, Kim DJ. The risk factors associated with subluxation of the distal interphalangeal joint in mallet fracture. J Hand Surg Eur Vol. 2015;40(1):63-67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lee HJ, Jeon IH, Kim PT, Oh CW, Deslivia MF, Lee SJ. Transtendinous wiring of mallet finger fractures presenting late. J Hand Surg Am. 2014;39(12):2383-2389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. McCarten GM, Bennett CS, Marshall DR. Treatment of mallet thumb. Aust N Z J Surg. 1986;56(3):285-286. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Miura T, Nakamura R, Torii S. Conservative treatment for a ruptured extensor tendon on the dorsum of the proximal phalanges of the thumb (mallet thumb). J Hand Surg Am. 1986;11(2):229-233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Nishimura R, Matsuura S, Miyawaki T, Uchida M. Bony mallet thumb. Hand Surg. 2013;18(1):107-109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Norrie BA, Jebson PJ. Mallet thumb. J Hand Surg Am. 2013;38(6):1219-1221; quiz 1222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Patel MR, Lipson LB, Desai SS. Conservative treatment of mallet thumb. J Hand Surg Am. 1986;11(1):45-47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Primiano GA. Conservative treatment of two cases of mallet thumb. J Hand Surg Am. 1986;11(2):233-235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tabbal GN, Bastidas N, Sharma S. Closed mallet thumb injury: a review of the literature and case study of the use of magnetic resonance imaging in deciding treatment. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;124(1):222-226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wehbe MA, Schneider LH. Mallet fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1984;66(5):658-669. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]