Abstract

The basic leucine zipper (bZIP) family of transcription factors plays an important role in the growth and developmental process as well as responds to various abiotic stresses, such as drought and high salinity. Our previous work identified GmFDL19, a bZIP transcription factor, as a flowering promoter in soybean, and the overexpression of GmFDL19 caused early flowering in transgenic soybean plants. Here, we report that GmFDL19 also enhances tolerance to drought and salt stress in soybean. GmFDL19 was determined to be a group A member, and its transcription expression was highly induced by abscisic acid (ABA), polyethylene glycol (PEG 6000) and high salt stresses. Overexpression of GmFDL19 in soybean enhanced drought and salt tolerance at the seedling stage. The relative plant height (RPH) and relative shoot dry weight (RSDW) of transgenic plants were significantly higher than those of the WT after PEG and salt treatments. In addition, the germination rate and plant height of the transgenic soybean were also significantly higher than that of WT plants after various salt treatments. Furthermore, we also found that GmFDL19 could reduce the accumulation of Na+ ion content and up-regulate the expression of several ABA/stress-responsive genes in transgenic soybean. We also found that GmFDL19 overexpression increased the activities of several antioxidative enzyme and chlorophyll content but reduced malondialdehyde content. These results suggested that GmFDL19 is involved in soybean abiotic stress responses and has potential utilization to improve multiple stress tolerance in transgenic soybean.

Introduction

Soybean plants are important economical crops and contribute to nearly 29% of globally consumed edible oil and 70% of world protein meal consumption [1]. Soybean oil is also used as a fuel source [2], and soybean products are used in pharmaceutical applications for their anti-cancerous properties [3]. In addition, being a legume crop, soybeans can improve nitrogen content in soil by fixing atmospheric nitrogen [4]. Such diverse uses of soybean make it a more wildly desired crop, and demand for soybean is rapidly increasing year after year [5, 6]. However, soybean yield is threatened by various abiotic stresses, such as drought and salt stresses [7, 8]. To improve drought and salt tolerant in soybean, a wide range of approaches, including gene discovery, QTL mapping, genome wide association studies (GWAS) and biotechnologcal approaches, can be used to facilitate the development of soybean varieties with improved drought and salt tolerance [6, 8]. Therefore, the identification and characterization of critical genes involved in stress responses is an essential prerequisite for engineering stress tolerant soybean.

In particular, drought and salt stresses have adverse effects on plants physiology and developmental processes mainly by disrupting ionic and osmotic homeostasis [9, 10]. Plants can adapt to these stress conditions by regulating the expression of a large number of stress-related genes. The genes encoding transcription factors (TFs) have been used in transgenic plants to enhance their tolerance to multiple abiotic stresses because of their roles as master regulators of many stress responsive genes [11]. Several stress responsive transcription factors, such as members of AP2/EREBP (APETALA2/ethylene responsive element binding protein), myeloblastosis (MYB), WRKY, NAC (NAM-no apical meristem, ATAF-Arabidopsis transcription activation factor and CUC-cup-shaped cotyledon), and bZIP families, are involved in plant abiotic stress responses, and some TF genes have also been engineered to improve stress tolerance in model plants and crops [11–14].

In soybean, 131 bZIP genes were identified and named as GmbZIPs. In total, 31 GmbZIPs were induced by salt stress [15]. Among these salt-induced GmbZIPs, four genes, including GmbZIP44, GmbZIP46, GmbZIP62 and GmbZIP78, whose protein products were shown to bind to GLM (GTGAGTCAT), ABRE (CCACGTGG) and PB-like (TGAAAA) cis-elements, were cloned and characterized. The Arabidopsis transgenic plants, which overexpressed GmbZIP44, GmbZIP62 or GmbZIP78, exhibited enhanced salt tolerance [14]. Recently, GmbZIP110, which is also induced by salt stress, has been identified in soybean [16]. GmbZIP110 protein bound to the “ACGT” motif and subsequently affected the expression of many stress-related genes. The accumulation of proline, Na+ and K+ in Arabidopsis transgenic plants was also affected, indicating the important role of GmbZIP110 in the regulation of soybean responses to saline stress [16].

The bZIP family of transcription factors plays an important role in developmental processes and responds to various abiotic stresses such as drought and high salinity stresses [17]. Our previous work showed that overexpression of GmFDL19, a bZIP transcription factor, caused early flowering in soybean [18]. To further analyze whether GmFDL19 has a function in abiotic stress in soybean, we investigated the drought and salt stress tolerance in seedlings. In addition, we evaluated the expression pattern of GmFDL19 in soybean seedlings under PEG, NaCl and ABA treatments. Furthermore, the regulation of Na+ ion accumulation in transgenic soybean plants and the transcription of several ABA/stress-responsive genes in soybean that overexpressed GmFDL19 were also investigated. Ultimately, the results of this study facilitate our understanding of GmFDL19 in response to abiotic stress as well as the genetic engineering of stress-tolerant soybean.

Materials and methods

Plant materials and abiotic stress treatments

The transgenic soybean plants that overexpressed GmFDL19 and wild type (WT) were used in this study. All plants were grown in soil and vermiculite at a 1:1 ratio in an artificial climate chamber under long day conditions (16 h light/ 8 h dark) at 25°C with an average light fluency of 200–300 μmol m-2s-1. Light was regulated by Master TL5 lamps (Philips). When the first trifoliate leaves fully expanded (one-week-old), the seedling roots were immersed in various stress treatments, i.e. PEG-simulated drought (15% PEG 6000), salinity (150 mM NaCl) and ABA (100 μM ABA). The seedlings were incubated for 0, 1, 6 and 12 h, and the first trifoliate leaves were collected at each time point. Three biological replicates were performed for each stress treatment. All samples were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until analyzed. Total RNA was isolated and reverse transcribed to obtain cDNA, which was used as a template for real-time quantitative RT-PCR.

For drought and salt tolerant tests, the experiments were conducted according to the previously described method by Cao et al. [19], with some modification. Seedlings were grown in soil and vermiculite at a 1:1 ratio. The transgenic soybean plants and wild type plants were planted in three pots, and each pot contained four seedlings. The six pots were put into a plastic container (150×75×25 cm). When the first trifoliate leaves fully expanded, the seedling roots were immersed in a solution of 15% PEG 6000 and 150 mM NaCl, respectively. Half-strength Hoagland solution was used as a control. Plant height was recorded 4 weeks after the treatment. Shoots were kept at 105°C for 48h and the dry weight was recorded. The relative plant height (RPH) was calculated as the ratio of the plant height under salt stress conditions to the average plant height under the control conditions. The relative shoot dry weight (RSDW) was calculated as the ratio of the shoot dry weight under salt stress conditions to the average shoot dry weight under the control conditions.

For the germination assay, 30 seeds of each transgenic soybean or WT were surface sterilized and placed on 1/2 Murashige and Skoog basal nutrient salts with B5 vitamins (MSB), supplemented with 0, 100, 200, 300 mM NaCl, respectively, under 16/8 h light-dark cycle condition at 25°C for 5 days. Images were taken at the end of each experiment, and the germination rate and plant height (the length from cotyledon to root tip) were recorded.

Real-time quantitative RT-PCR analyses

Total RNA was isolated, and cDNA was synthesized as described by Nan et al. [18]. The quantitative RT-PCR mixture was prepared by mixing a 1 μL aliquot of the reaction mixture from the cDNA synthesis, 5 μL of 1.2 μM primer premix, 10 μL SYBR Premix ExTaq Perfect Real Time (TaKaRa Bio), and water to a final volume of 20 μL. The analysis was conducted using the DNA Engine Opticon 2 System (Bio-Rad). The PCR cycling conditions were as follows: 95°C for 10 s, 55°C to 60°C (depending on the gene) for 20 s, 72°C for 20 s, and 78°C for 2 s. This cycle was repeated 40 times. Fluorescence quantification was conducted before and after incubation at 78°C to monitor the formation of primer dimers. The mRNA level of the Tubulin gene was used as a control for the analysis. A reaction mixture without reverse transcriptase was also used as a control to confirm that no amplification occurred from genomic DNA contaminants in the RNA sample. In all of the PCR experiments, the amplification of a single DNA species was confirmed using both a melting curve analysis of the quantitative PCR and gel electrophoresis of the PCR products. The primers used for real-time quantitative RT-PCR are listed in S1 Table.

Expression analysis of stress-responsive genes

Soybean seeds were grown in a pot with vermiculite. After emergence, the seedlings were transferred into a plastic container filled with half-strength Hoagland (pH = 6.5). A week after transplantation, the seedlings were treated with half-strength Hoagland with 150 mM of NaCl and 15% PEG 6000, respectively. The roots were collected 48h after treatment. All samples were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until analyzed. Total RNA was isolated and reverse transcribed to obtain cDNA, which was used as a template for real-time quantitative RT-PCR.

The expression of stress-related genes listed in S1 Table was determined from root samples. Three biological replicates were performed for each stress treatment. The mRNA level of the Tubulin gene was used as a control for the analysis.

Measurement of Na+ and K+ contents

Plants were treated with NaCl according the method described previously with some modification [20]. In brief, soybean seeds were grown in a pot with vermiculite. After emergence, the seedlings were transferred into a plastic container (150×75×25 cm) filled with half-strength Hoagland (pH = 6.5). A week after the transplantation, the seedlings were treated with half-strength Hoagland (pH = 6.5) with or without 70 mM of NaCl. After five days, NaCl concentration was increased to 150 mM. Two days later, five seedling of transgenic and WT plants were used for the analysis of Na+ and K+ contents. Shoot and root samples were ground into powder, and 10 mL of 100 mM acetic acid was added. Samples were incubated at 90°C for 3 h. Sodium and potassium contents were determined using inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectrometry (ICPS-7500, Japan). The analysis was repeated in triplicate.

Measurement of antioxidant enzyme activities, malondialdehyde and chlorophyll concentration

Plants were treated with 150 mM NaCl for 2 weeks according the method described above. The activity of antioxidant enzyme, including superoxide dismutase (SOD), peroxidase (POD) and catalase (CAT), and the concentration of malondialdehyde (MDA) and chlorophyll were measured as the methods described previously [21]. Three biological replicates were performed for each treatment. All of the experiments were carried out three times.

Statistical analysis

All data were processed by analysis of SPSS 13.0 Data Editor. Values of P<0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Expression of GmFDL19 under different stress treatments

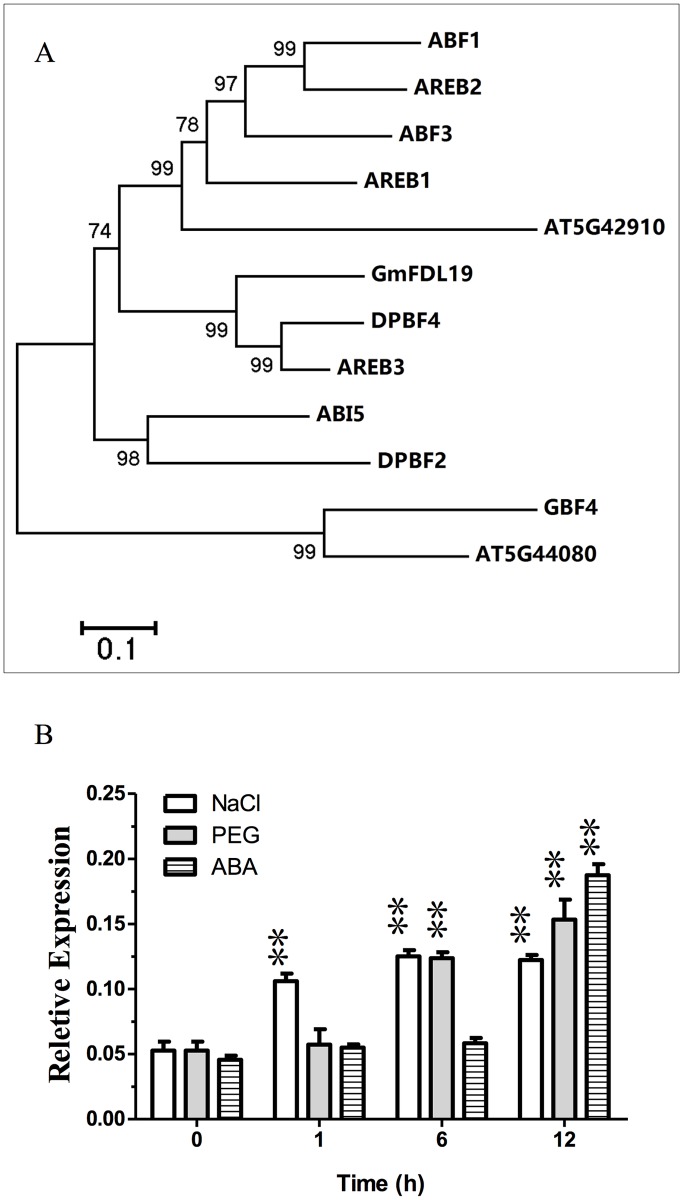

Our previous study showed that overexpression of GmFDL19 caused early flowering in soybean, and the electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) indicated that GmFDL19 could bind with abscisic acid response element (ABRE) like sequences (ACGT core elements) [18]. In the current study, cluster analysis showed that GmFDL19 exhibited high similarity of amino acid sequences to the group-A bZIP in Arabidopsis (Fig 1A). Most of members of group A, which are classified as homologs of AREB/ABFs, have roles in abscisic acid (ABA) or stress signaling [17, 22]. Thus, GmFDL19 might be a member of ABF/AREB, participating in ABA and abiotic stress signaling.

Fig 1. Phylogenetic tree and analysis of expression patterns of GmFDL19.

(A) Phylogenetic tree containing the full length of GmFDL19 and 11 Arabidopsis bZIP proteins (group A), using the Neighbor-Joining method with the MEGA software. (B) The expression patterns of GmFDL19 in leaves, when WT plants were subjected to 150 mM NaCl, 15% PEG and 100 μM ABA treatments. P-values were calculated using Student’s t-test. **P < 0.01 compared with 0h.

To clarify the expression of GmFDL19, real-time quantitative RT-PCR was performed using one-week-old soybean seedlings (the first trifoliate leaves fully expanded) subjected to various stresses. The transcript abundance of GmFDL19 was increased when the seedlings were exposed to NaCl stress for 1 h, and reached a peak value after 6 h (Fig 1B). No change in the expression of GmFDL19 was observed after 1 h of PEG treatment, but the gene expression was up-regulated after 6 h (Fig 1B). The expression of GmFDL19 was also induced after 12 h of ABA treatment, suggesting that this gene is also responsive to ABA (Fig 1B). These results indicated that GmFDL19 was also induced by abiotic stresses, participating in the ABA-dependent osmotic stress response.

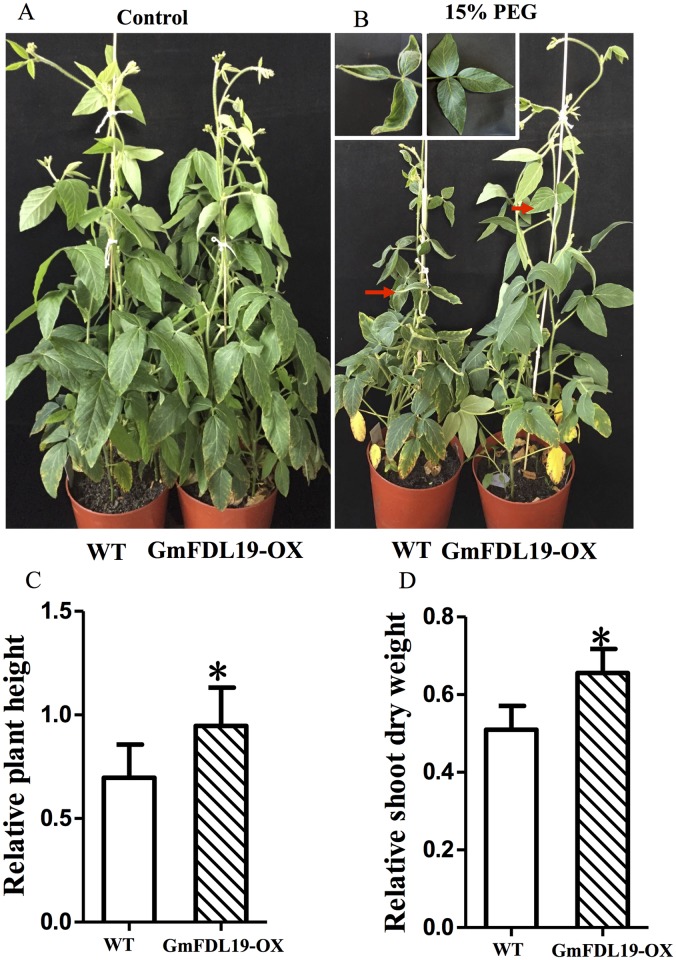

Overexpression of GmFDL19 increased tolerance to drought stress in transgenic soybeans

Since GmFDL19 may be a member of ABF/AREB and its expression was induced by PEG treatment, the function of transgenic soybean plants overexpressing GmFDL19 were investigated under PEG treatment. The phenotype of soybean plants that overexpress GmFDL19 was examined under PEG treatment. As shown in Fig 2A, no significant difference in phenotype was observed for the transgenic plants when compared with the wild type (WT) plants under normal conditions. The one-week-old soybean seedlings were treated with 15% PEG 6000 for 4 weeks. During this time, the shoot of transgenic plants grew stronger and higher, whereas the leaves of WT plants curled and exhibited signs of dwarfism (Fig 2B). Moreover, the RPH and RSDW of transgenic plants were significantly higher than those of the WT (Fig 2C and 2D). Similar results were observed under natural dry treatment (S1 Fig). These results suggested that GmFDL19 overexpression could improve the response to drought stress in transgenic soybean.

Fig 2. Effects of PEG on soybean that overexpress GmFDL19.

Photographs were taken at the end of PEG treatment of normal condition (A) and PEG treatment (B). The relative plant height (C) and relative dry weight of shoots (D) were calculated as the ratio of the values under salt stress conditions to the value under control condition. P-values were calculated using Student’s t-test. *P < 0.05 compared with WT.

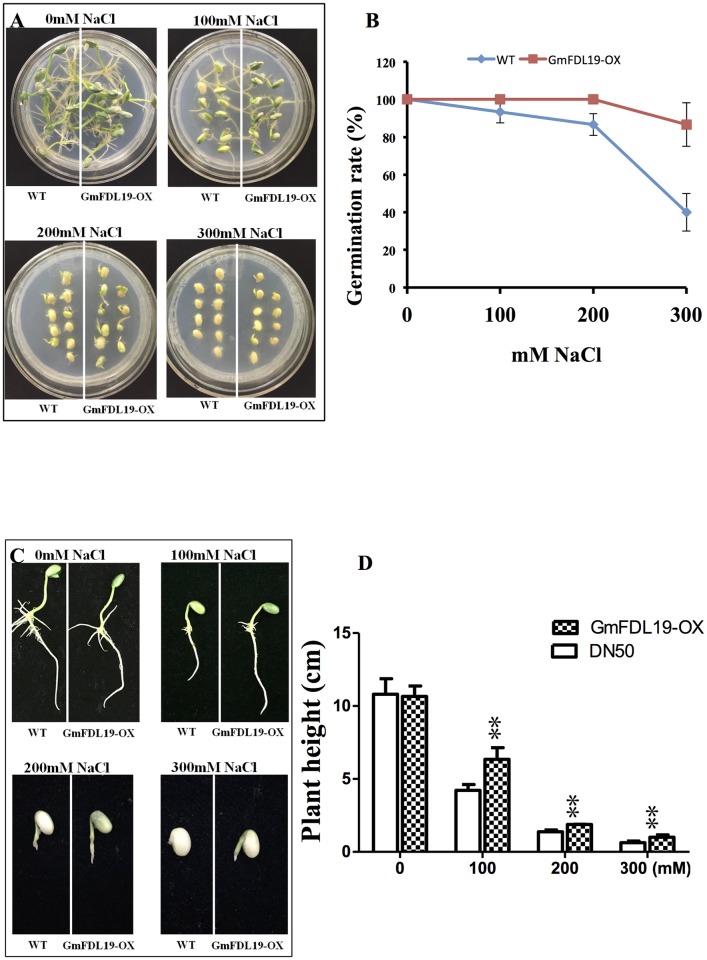

Overexpression of GmFDL19 increased tolerance to salt stress in transgenic soybeans

To determine the change in response to high salt conditions of transgenic plants, the seeds of soybean that overexpress GmFDL19 and WT seeds were placed on germination medium (1/2MSB with 2% sucrose) containing various concentrations of NaCl for 5 days. Under normal conditions, there was no obvious difference in phenotypes of the transgenic and WT seedlings (Fig 3). After a 200 mM NaCl treatment, the WT seeds had a lower germination rate (86.7%) than the transgenic seeds (100%), as depicted in Fig 3A and 3B. After a 300 mM NaCl treatment, the germination rate of the transgenic seeds began to decrease but was still significantly higher (86.6%) than that of WT (40%). Furthermore, although the salt stress had detrimentally affected growth rate of both transgenic and WT seedlings, the plant height of the transgenic seedlings was significantly higher than that of WT seedlings after salt treatment (Fig 3C and 3D). These results suggested that GmFDL19 overexpression could increase salt tolerance in soybean germination.

Fig 3. Salt tolerance of germination assay.

(A) The images were taken at the end of experiment and then the germination rate (B) was recorded. (C) The images of whole seedlings were taken after washing. (D) The plant height of WT and transgenic lines under different concentrations of NaCl treatment. P-values were calculated using Student’s t-test. **P < 0.01 compared with WT.

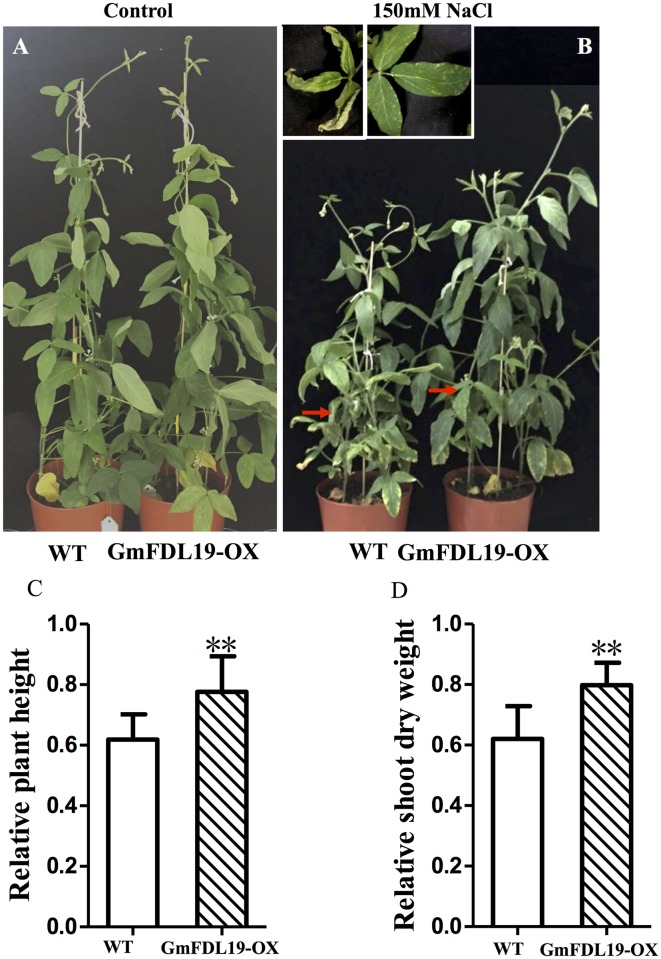

To further test the salt-tolerant phenotype of soybean plants that overexpress GmFDL19, the one-week-old soybean seedlings were treated with 150 mM NaCl for 4 weeks. The WT plants displayed chlorosis after 150 mM NaCl treatment. Additionally, a general growth inhibition was observed, specifically less plant height and dry mass, when compared with the controls (Fig 4). Although the inhibitory effect was also observed in transgenic plants, the transgenic plants had a significantly higher RPH and RSDW than the WT (Fig 4). The RPH and RSDW of the transgenic plants were 0.78 and 0.79, respectively, whereas the RPH and RSDW of WT were 0.61 and 0.59, respectively (Fig 4C and 4D). In addition, the WT plants died after 3 weeks with salt treatment at 200 mM NaCl, whereas transgenic plants still survived well with less inhibition (S2 Fig). These results further confirmed that GmFDL19 overexpression could improve the salt tolerance in transgenic soybean seedlings.

Fig 4. Effect of salt stress on soybean seedlings that overexpress GmFDL19.

Photographs were taken at the end of salt treatment of normal condition (A) and 150 mM NaCl treatment (B). The relative plant height (C) and relative dry weight of shoots (D) were calculated as the ratio of the values under salt stress conditions to the value under control condition. P-values were calculated using Student’s t-test. **P < 0.01 compared with WT.

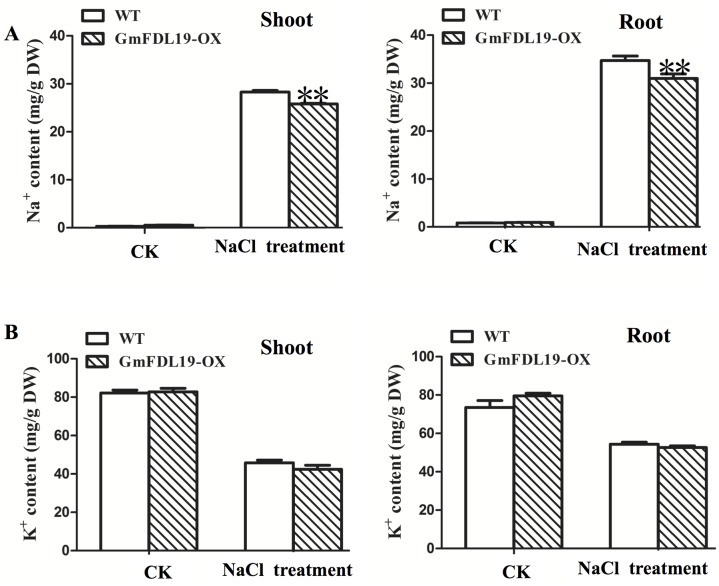

Na+ and K+ contents in transgenic soybean under salt stress

Since the GmFDL19 gene could improve salinity tolerance response in transgenic plants, GmFDL19 may also have a role in regulating the Na+ absorption. Under control treatment (CK), both transgenic plants and WT plants taken up less than 1.0 mg Na+ per g of dry weight (DW) in shoots and roots (Fig 5A). Under NaCl treatment, Na+ content in shoots and roots of transgenic and WT plants were increased above 20 mg Na+ per g of DW. However, Fig 5A showed significantly lower Na+ content in shoot and root of transgenic plants than that of the WT plants under NaCl treatment. WT plants took up 28.3 and 34.7 mg Na+ per g of DW in shoots and roots respectively, whereas, the transgenic plants took up 25.6 and 31.2 mg Na+ per g of DW in shoots and roots respectively under NaCl treatment (Fig 5A). The transgenic plants and WT plants had a higher K+ contents in control than that in salt stress conditions (Fig 5B). This were consistent with the result that both transgenic and WT plants had a low plant height under salt stress (Fig 4). No significant differences in K+ content were observed between the WT and transgenic plants (Fig 5B). These results indicated that GmFDL19 plays a role in regulating absorption of Na+ in soybean.

Fig 5. Na+ and K+ contents in shoots and roots of soybean plants that overexpress GmFDL19 after salt treatment.

(A) Na+ ion uptake in shoots and roots. (B) K+ ion uptake in shoots and roots. P-values were calculated using Student’s t-test. *P < 0.05 compared with WT.

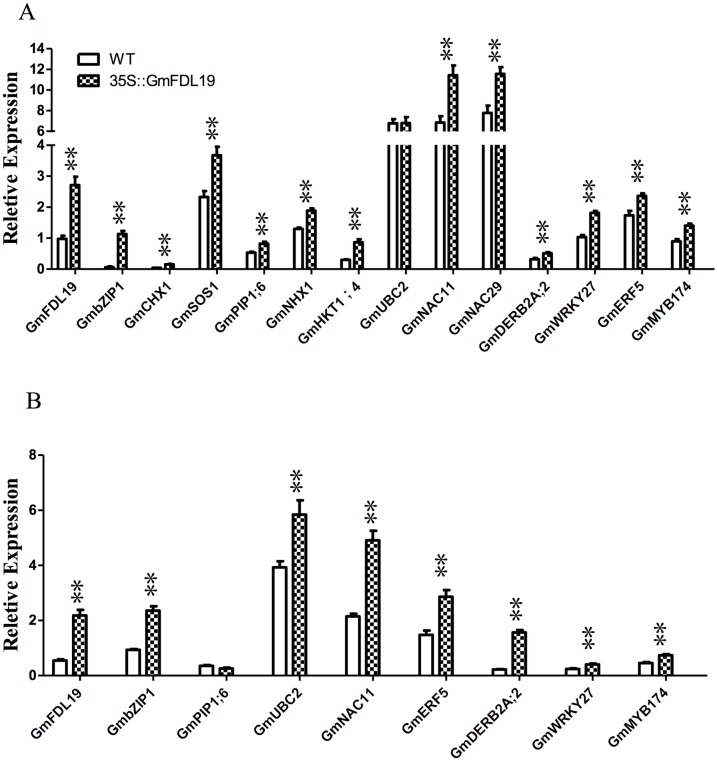

The expression of stress-responsive genes in transgenic soybean

The GmFDL19 gene might have a role in improving stress tolerance through the regulation of downstream genes. As shown in Fig 6A, the transcript abundance of five reported salt-responsive genes, such as GmCHX1 [20,23, 24], GmSOS1 [25], GmPIP1;6 [26], GmNHX1 [27] and GmNKT1;4 [28], increased significantly in the transgenic soybean plants compared with that in WT under salt stress conditions. In addition, seven TF genes, including GmbZIP1, GmNAC11, GmNAC29, GmDERB2A;2, GmWRKY27, GmERF5 and GmMYB174, which have been involved in salt stress responses in soybean [29–33], also increased significantly in the transgenic soybean plants compared with that in WT after the 150 mM NaCl treatment (Fig 6A). Similar to the results observed under the salt stress condition, the expression of all seven TF genes in transgenic plants was higher than that in WT plants under PEG treatment (Fig 6B). The relative expression of GmUBC2, which might improve drought and salt tolerance in soybean [34], was similar in WT and transgenic plants after the 150mM NaCl treatment (Fig 6A), whereas, the expression of GmUBC2 was lower in WT than in transgenic plants after the PEG treatment (Fig 6B). These results indicated that GmFDL19 regulated a common set of ABA and stress responsive genes in soybean.

Fig 6. Downstream gene expression in the transgenic soybean overexpressing GmFDL19 after salt or PEG treatment for 2 days.

(A) Relative transcript abundance of salt-related genes in roots of transgenic soybean that overexpress GmFDL19 after salt treatment for 2 days. (B) Relative transcript abundance of salt-related genes in roots of transgenic soybean that overexpress GmFDL19 after PEG treatment for 2 days. The Tubulin gene was used as a control for the analysis. P-values were calculated using Student’s t-test. **P < 0.01 compared with WT.

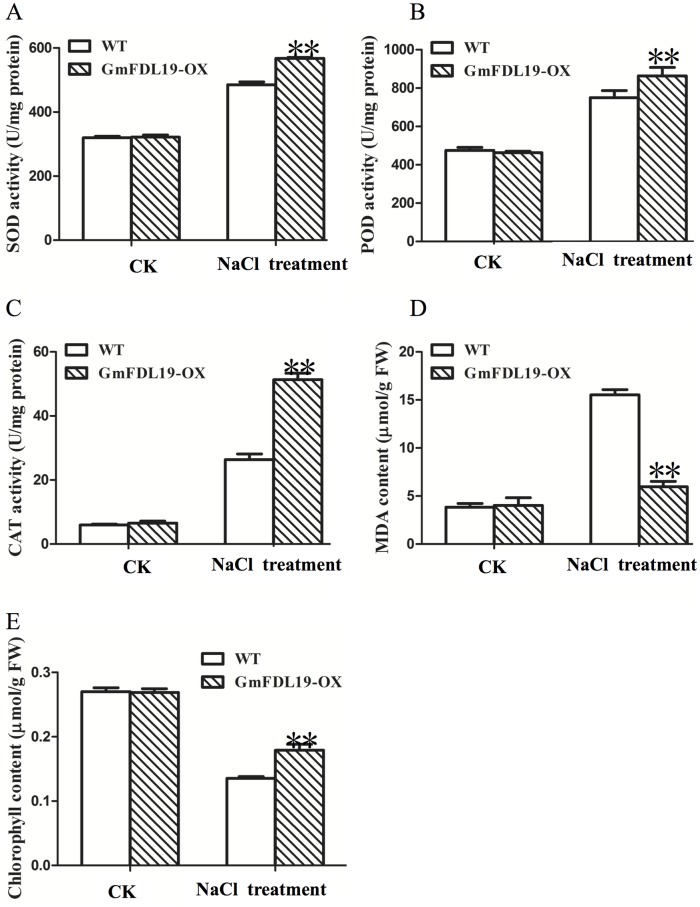

Physiological changes in transgenic soybeans under salt treatment

Salt stress can also induce oxidative stress by continuously producing reactive oxygen species (ROS) [35]. To investigate the possible mechanism of salt tolerance in transgenic soybean plants overexpressing GmFDL19, we analyzed the activities of antioxidant enzyme (SOD, POD and CAT) and the content of MDA under salt treatment. Under CK conditions, both transgenic and WT plants have a low activities of SOD, POD and CAT and low level of MDA (Fig 7A–7D). However, after salt treatment, transgenic plants displayed significantly higher activities of SOD, POD and CAT, but a lower level of MDA compared with WT plants (Fig 7A–7C). These results suggested that GmFDL19 may enhance the activity of antioxidant enzyme and reduce the accumulation of MDA, thus reducing the ROS and increasing salt tolerance in soybean. In addition, previous study indicated that slat tolerance soybean plants always had high chlorophyll content [36]. Fig 7E showed that the chlorophyll contents were high in control conditions and low in salt stress conditions. However, the chlorophyll in transgenic plants was significantly higher than that in WT plants after salt treatment (Fig 7E), consistent with the results that transgenic plants displayed salt tolerance.

Fig 7. Effect of GmFDL19 overexpression on antioxidant enzymes, MDA and chlorophyll contents in transgenic and WT plants after salt treatment.

(A) superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity. (B) Peroxidase (POD) activity. (C) Catalase (CAT) activity. (D) Malondialdehyde (MDA) content. (E) chlorophyll content in leaves of transgenic and WT plants grown in 150 mM NaCl for 2 weeks. P-values were calculated using Student’s t-test. **P < 0.01 compared with WT.

Discussion

In maize [37, 38], wheat [39] and rice [40], studies have shown that overexpressing the stress-responsive bZIP genes can improve drought and salinity tolerance in transgenic plant. In soybean, the GmbZIP genes, such as GmbZIP44, GmbZIP62, GmbZIP78, GmbZIP132, GmbZIP110 and GmbZIP1, were responsive to multiple stress treatment [15, 16, 33, 41]. In the present study, the results showed that the GmFDL19, which has a high amino acid sequence similar to the Arabidopsis ABF/AREB subfamily members, was determined to be a group A member (Fig 1A). In Arabidopsis, the ABF/AREB subfamily genes were involved in ABA and stress signaling pathways [17, 22]. Here, we also found that the expression of GmFDL19 was induced by multiple stresses, including PEG, high salt and ABA (Fig 1B). These results were consistent with the expression of GmbZIP1, which is also a group A member in soybean and highly induced by ABA, drought, high salt, and low temperature [33]. These results indicated that the GmFDL19, a novel group A bZIP gene, might play a role in abiotic stress tolerance in soybean.

The transgenic soybean plants overexpressing GmFDL19 showed a greater tolerance to PEG and salt treatment compared to WT plants (Figs 2–4). Similar phenotypic parameters were observed under PEG and salt treatment using transgenic line overexpressing GmFDL06, another member of ABF/AREB family [42]. Our data showed that both GmFDL19 overexpression line and GmFDL06 overexpression line showed an improvement of salt and drought tolerance compared with the wild type [42, Figs 2–4]. Thus, we thought that the enhancement of tolerance to drought and salt stresses in transgenic soybean overexpressing GmFDL19, was due to the GmFDL19 overexpression, not other genes in soybean genome. Moreover, these results were consistent with the description that the overexpression of GmbZIP1 improved tolerance to high salt and drought in transgenic plants [33]. In addition, previous studies have found that the Arabidopsis transgenic plants that overexpress three non-AREB subfamily bZIP genes (GmbZIP44, GmbZIP62 or GmbZIP78) exhibited enhanced salt tolerance [15]. Recently, GmbZIP110 that is also induced by salt stress, has been identified in soybean, and an enhanced salt tolerance of composite seedling and transgenic Arabidopsis was observed [16]. The transgenic Arabidopsis that overexpress GmbZIP110 took up significantly less Na+ ion, while no significant change in K+ ion uptake was measured [16]. Our results showed that the transgenic soybean overexpressing GmFDL19 also have a significantly lower Na+ ion content, with no significant change in K+ and Cl- content when compared to WT plants (Fig 5). Thus, GmFDL19 might function in regulating absorption of Na+, and in turn, might improve salt tolerance in soybean. This suggests that different bZIP subfamilies in soybean may play similar roles in resisting abiotic stresses.

Overexpression of GmbZIP genes can up-regulate the expression levels of a number of ABA/stress-responsive genes in Arabidopsis [15, 16, 33]. However, the function of GmbZIP genes on the regulation of target genes remains unclear in soybean. Our findings showed that the overexpression of GmFDL19 up-regulated the expression of salt-related genes and some TF genes in transgenic soybean plants after salt and PEG treatments (Fig 6). The GmCHX1 gene plays an important role in Na+ transportation and salt tolerance in soybean [20,23,24]. The overexpression of GmSOS1, GmPIP1;6, GmNHX1 and GmHKT1;4 reduced Na+ uptake and improved salt tolerance in transgenic plants [25–28]. In order to dissect the reduction of Na+ uptake and enhancement of salt tolerance at the molecular level, the expression of these salt-related genes were analyzed. The results showed that the salt-related genes, including GmCHX1, GmSOS1, GmPIP1;6, GmNHX1, and GmNKT1;4, increased in transgenic soybean post salt treatment (Fig 6A). In addition, overexpression of GmUBC2 enhanced drought and salt tolerance of Arabidopsis transgenic plants through modulating expression of abiotic stress-responsive genes [34]. Furthermore, some TF genes, including GmbZIP1, GmNAC11, GmNAC29, GmDERB2A;2, GmWRKY27, GmERF5 and GmMYB174, are involved in plant abiotic stress responses in ABA-dependent pathways [29–33]. The expression of these TF genes was also analyzed, and we found that these genes also increased in transgenic soybean plants that overexpress GmFDL19 (Fig 6). These results indicated that GmFDL19 might be involved in ABA dependent pathways and is also related to ion transport similar to Arabidopsis.

The plant bZIP proteins preferentially bind to DNA sequences with an ACGT core, and previous study showed that GmFDL19 was able to bind with ACGT core elements [17,18]. We inferred that GmFDL19 might act as an activator to increase the expression of these genes; therefore, we searched for cis-elements in the 2-kb promoter region upstream of ATG in the phytozome (http://www.phytozome.net). S2 Table showed that the promoter has two to six ACGT core elements, and the data indicates that overexpression of GmFDL19 up-regulated the ABA/stress-responsive genes might via directly binds to their ACGT core elements.

In plants, salt stress can overproduced ROS, such as H2O2 and MDA, which could cause many adverse effects to the plant cell [35, 43]. In soybean, one possible mechanism of salt tolerance is to enhance the contents and activities of antioxidative enzyme to restore the oxidative balance and minimize the cellular damage by secondary oxidative stress [7]. In soybean, the purple acid phosphatase 3 (GmPAP3), encoding a purple acid phosphatase that localizes in mitochondria, was shown to be induced by salinity, osmotic and oxidative stresses [44, 45]. Ectopic expression of GmPAP3 could alleviate the oxidative damage caused by salinity and osmotic stresses [44]. Silencing two GmFNSII genes in soybean plants reduced the production of flavones aglycones, resulting in more MDA and H2O2 accumulation, and then hypersensitivity to salt stress as compared with control plants [46]. Recent research showed that GmWRKY27 improves salt and drought tolerance in soybean; partly via reduce ROS level [29]. GmWRKY27 interacts with GmMYB174, and the two TFs cooperatively inhibit transcription of GmNAC29, whose product may be involved in ROS production by directly increasing the expression of GmSPOD1, leads to reduced intracellular ROS levels [29]. Our data showed that the transgenic soybean plants overexpressing GmFDL19 displayed lower level MDA and higher level of antioxidant enzymes activities and chlorophyll contents (Fig 7), which is consistent with the salt tolerance phenotype (Fig 4). Our results suggested that GmFDL19 may reduce the ROS and then increase salt tolerance in soybean. Further studies are needed to better understand how GmFDL19 reduces the ROS in soybean.

In conclusion, overexpression of GmFDL19 improved the drought and salt tolerance in soybean. GmFDL19 might directly bind to ACGT core elements and up-regulate several ABA/stress-responsive genes. In addition, overexpression of GmFDL19 regulated the absorption of Na+ but not K+ or Cl-, in transgenic plants. Our data suggests that GmFDL19 is involved in soybean abiotic stress responses and has a potential utilization to improve multiple stress tolerance in transgenic soybean.

Supporting information

Photographs were taken of cnotrol condition (A) and natural dry treatment (B). Water was provided to the well-watered control to maintain the volumetric soil moisture content (SMC) at 50–55%. For natural dry treatment, the 7-day-old seedlings were water withheld for 3 weeks, where the SMC was below 17%. At the end of treatment, the plant height and dry weight were measured. The relative plant height (C) and relative dry weight of shoots (D) were calculated as the ratio of the values under salt stress conditions to the value under control condition. P-values were calculated using Student’s t-test. *P < 0.05 compared with WT.

(TIFF)

Photographs were taken at the end of salt treatment of normal condition (A) and 200 mM NaCl treatment (B). The relative plant height (C) and relative dry weight of shoots (D) were calculated as the ratio of the values under salt stress conditions to the value under control condition. P-values were calculated using Student’s t-test. **P < 0.01 compared with WT.

(TIFF)

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Kan Wang for providing the soybean transformation vector pTF101.1 and the Agrobacterium strain EHA101. We also thank Professor Shuzhen Zhang for providing soybean cultivar Dongnong 50. We thank LetPub (www.letpub.com) for its linguistic assistance during the preparation of this manuscript.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

This work was supported in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grants 31430065, 31371643, and 31571686), the Open Foundation of the Key Laboratory of Soybean Molecular Design Breeding, Chinese Academy of Sciences, the Strategic Action Plan for Science and Technology Innovation of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (XDA08030108) to B. Liu and F. Kong; the Heilongjiang Natural Science Foundation of China [ZD201001, JC201313]; the Research and Development of Applied Technology Project, Harbin [2014RFQY055].

References

- 1.Soystats, 2016. A publication of the American soybean association. http://www.soystats.com.

- 2.Qi DH, Lee CF. Influence of soybean biodiesel content on basic properties of biodiesel-diesel blends. J Taiwan Inst Chem E. 2014;45: 504–507. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ko KP, Park SK, Yang JJ, Ma SH, Gwack J, Shin A, et al. Intake of soy products and other foods and gastric cancer risk: a prospective study. J Epidemiol. 2013;23: 337–343. doi: 10.2188/jea.JE20120232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sulieman S, Ha CV, Esfahani MN, Watanabe Y, Nishiyama R, Pham CTB, et al. DT2008: A promising new genetic resource for improved drought tolerance in soybean when solely dependent on symbiotic N2 fixation. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015: 687213 doi: 10.1155/2015/687213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ray DK, Mueller ND, West PC, Foley JA. Yield trends are insufficient to double global crop production by 2050. Plos One. 2013;8: e66428 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0066428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deshmukh R, Sonah H, Patil G, Chen W, Prince S, Mutava R, et al. Integrating omic approaches for abiotic stress tolerance in soybean. Front Plant Sci. 2014;5: 244 doi: 10.3389/fpls.2014.00244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Phang TH, Shao GH, Lam HM. Salt tolerance in soybean. J Integr Plant Biol. 2008;50: 1196–1212. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7909.2008.00760.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Manavalan LP, Guttikonda SK, Tran LSP, Nguyen HT. Physiological and molecular approaches to improve drought resistance in soybean. Plant Cell Physiol. 2009;50: 1260–1276. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcp082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ruan CJ, Teixeira da Silva JAT. Metabolomics: Creating new potentials for unraveling the mechanisms in response to salt and drought stress and for the biotechnological improvement of xero-halophytes. Crit Rev Biotechnol. 2011;31: 153–169. doi: 10.3109/07388551.2010.505908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khan MS, Khan MA, Ahmad D. Assessing utilization and environmental risks of important genes in plant abiotic stress tolerance. Front Plant Sci. 2016;7: 792 doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.00792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang HY, Wang HL, Shao HB, Tang XL. Recent advances in utilizing transcription factors to improve plant abiotic stress tolerance by transgenic technology. Front Plant Sci. 2016;7: 67 doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.00067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tran LSP, Mochida K. Functional genomics of soybean for improvement of productivity in adverse conditions. Funct Integr Genomic. 2010;10: 447–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thao NP, Tran LSP. Potentials toward genetic engineering of drought-tolerant soybean. Crit Rev Biotechnol. 2012;32: 349–362. doi: 10.3109/07388551.2011.643463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jogaiah S, Govind SR, Tran LSP. Systems biology-based approaches toward understanding drought tolerance in food crops. Crit Rev Biotechnol. 2013;33: 23–39. doi: 10.3109/07388551.2012.659174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liao Y, Zou HF, Wei W, Hao YJ, Tian AG, Huang J, et al. Soybean GmbZIP44, GmbZIP62 and GmbZIP78 genes function as negative regulator of ABA signaling and confer salt and freezing tolerance in transgenic Arabidopsis. Planta. 2008;228: 225–240. doi: 10.1007/s00425-008-0731-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xu ZL, Ali Z, Xu L, He XL, Huang YH, Yi JX, et al. The nuclear protein GmbZIP110 has transcription activation activity and plays important roles in the response to salinity stress in soybean. Sci Rep-Uk. 2016;6: 20366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jakoby M, Weisshaar B, Droge-Laser W, Vicente-Carbajosa J, Tiedemann J, Kroj T, et al. bZIP transcription factors in Arabidopsis. Trends Plant Sci. 2002;7: 106–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nan HY, Cao D, Zhang DY, Li Y, Lu SJ, Tang LL, et al. GmFT2a and GmFT5a redundantly and differentially regulate flowering through interaction with and upregulation of the bZIP transcription factor GmFDL19 in soybean. Plos One. 2014;9: e97669 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0097669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cao D, Hou WS, Liu W, Yao WW, Wu CX, Liu XB, et al. Overexpression of TaNHX2 enhances salt tolerance of 'composite' and whole transgenic soybean plants. Plant Cell Tiss Org. 2011;107: 541–552. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Do TD, Chen HT, Vu HTT, Hamwieh A, Yamada T, Sato T, et al. Ncl synchronously regulates Na+, K+, and Cl- in soybean and greatly increases the grain yield in saline field conditions. Sci Rep-Uk. 2016;6: 19147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gong X, Yin L, Chen J, Guo C. Overexpression of the iron transporter NtPIC1 in tobacco mediates tolerance to cadmium. Plant Cell Rep. 2015; 34: 1963–1973. doi: 10.1007/s00299-015-1843-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fujita Y, Yoshida T, Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K. Pivotal role of the AREB/ABF-SnRK2 pathway in ABRE-mediated transcription in response to osmotic stress in plants. Physiol Plantarum. 2013;147: 15–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Qi XP, Li MW, Xie M, Liu X, Ni M, Shao GH, et al. Identification of a novel salt tolerance gene in wild soybean by whole-genome sequencing. Nat Commun. 2014;5: 4340 doi: 10.1038/ncomms5340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guan RX, Qu Y, Guo Y, Yu LL, Liu Y, Jiang JH, et al. Salinity tolerance in soybean is modulated by natural variation in GmSALT3. Plant J. 2014;80: 937–950. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nie WX, Xu L, Yu BJ. A putative soybean GmsSOS1 confers enhanced salt tolerance to transgenic Arabidopsis sos1-1 mutant. Protoplasma. 2015;252: 127–134. doi: 10.1007/s00709-014-0663-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhou L, Wang C, Liu RF, Han Q, Vandeleur RK, Du J, et al. Constitutive overexpression of soybean plasma membrane intrinsic protein GmPIP1;6 confers salt tolerance. Bmc Plant Biol. 2014;14: 181 doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-14-181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sun YX, Wang D, Bai YL, Wang NN, Wang Y. Studies on the overexpression of the soybean GmNHX1 in Lotus corniculatus: The reduced Na+ level is the basis of the increased salt tolerance. Chinese Sci Bull. 2006;51: 1306–1315. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen HT, Chen X, Gu HP, Wu BY, Zhang HM, Yuan XX, et al. GmHKT1;4, a novel soybean gene regulating Na+/K+ ratio in roots enhances salt tolerance in transgenic plants. Plant Growth Regul. 2014;73: 299–308. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang F, Chen HW, Li QT, Wei W, Li W, Zhang WK, et al. GmWRKY27 interacts with GmMYB174 to reduce expression of GmNAC29 for stress tolerance in soybean plants. Plant J. 2015;83: 224–236. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dong LD, Cheng YX, Wu JJ, Cheng Q, Li WB, Fan SJ, et al. Overexpression of GmERF5, a new member of the soybean EAR motif-containing ERF transcription factor, enhances resistance to Phytophthora sojae in soybean. J Exp Bot. 2015;66: 2635–2647. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erv078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hao YJ, Wei W, Song QX, Chen HW, Zhang YQ, Wang F, et al. Soybean NAC transcription factors promote abiotic stress tolerance and lateral root formation in transgenic plants. Plant J. 2011;68: 302–313. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04687.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mizoi J, Ohori T, Moriwaki T, Kidokoro S, Todaka D, Maruyama K, et al. GmDREB2A;2, a canonical DEHYDRATION-RESPONSIVE ELEMENT-BINDING PROTEIN2-Type transcription factor in soybean, is posttranslationally regulated and mediates dehydration-responsive element-dependent gene expression. Plant Physiol. 2013;161: 346–361. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.204875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gao SQ, Chen M, Xu ZS, Zhao CP, Li LC, Xu HJ, et al. The soybean GmbZIP1 transcription factor enhances multiple abiotic stress tolerances in transgenic plants. Plant Mol Biol. 2011;75: 537–553. doi: 10.1007/s11103-011-9738-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhou GA, Chang RZ, Qiu LJ. Overexpression of soybean ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme gene GmUBC2 confers enhanced drought and salt tolerance through modulating abiotic stress-responsive gene expression in Arabidopsis. Plant Mol Biol. 2010;72: 357–367. doi: 10.1007/s11103-009-9575-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miller G, Suzuki N, Ciftci-Yilmaz S, Mittler R. Reactive oxygen species homeostasis and signalling during drought and salinity stresses. Plant Cell Environ. 2010;33:453–467. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2009.02041.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tuyen DD, Lal SK, Xu D. Identification of a major QTL allele from wild soybean (Glycine soja Sieb. & Zucc.) for increasing alkaline salt tolerance in soybean. Theor Appl Genet. 2010; 121: 229–236. doi: 10.1007/s00122-010-1304-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang X, Wang L, Meng H, Wen HT, Fan YL, Zhao J. Maize ABP9 enhances tolerance to multiple stresses in transgenic Arabidopsis by modulating ABA signaling and cellular levels of reactive oxygen species. Plant Mol Biol. 2011;75: 365–378. doi: 10.1007/s11103-011-9732-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ying S, Zhang DF, Fu J, Shi YS, Song YC, Wang TY, et al. Cloning and characterization of a maize bZIP transcription factor, ZmbZIP72, confers drought and salt tolerance in transgenic Arabidopsis. Planta. 2012;235: 253–266. doi: 10.1007/s00425-011-1496-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang LN, Zhang LC, Xia C, Zhao GY, Liu J, Jia JZ, et al. A novel wheat bZIP transcription factor, TabZIP60, confers multiple abiotic stress tolerances in transgenic Arabidopsis. Physiol Plantarum. 2015;153: 538–554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu CT, Mao BG, Ou SJ, Wang W, Liu LC, Wu YB, et al. OsbZIP71, a bZIP transcription factor, confers salinity and drought tolerance in rice. Plant Mol Biol. 2014;84: 19–36. doi: 10.1007/s11103-013-0115-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liao Y, Zhang JS, Chen SY, Zhang WK. Role of soybean GmbZIP132 under abscisic acid and salt stresses. J Integr Plant Biol. 2008;50: 221–230. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7909.2007.00593.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li Y, Nan H, Liu B, Kong F, Guo C. Study on drought resistance and salt tolerance of soybean gene GmFDL06. Soyb Sci. 2017;36: 351–359 (in Chinese with english abstract). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fath A, Bethke PC, Belligni MV, Spiegel YN, Jones RL. Signalling in the cereal aleurone: hormones, reactive oxygen and cell death. New Phytol. 2001;151: 99–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liao H, Wong F, Phang T, Cheung M, Li WF, Shao G, Yan X, Lam H. GmPAP3, a novel purple acid phosphatase-like gene in soybean induced by NaCl stress but not phosphorus deficiency. Gene. 2003;318: 103–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li WF, Shao G, Lam H. Ectopic expression of GmPAP3 alleviates oxidative damage caused by salinity and osmotic stresses. New Phytol. 2008; 78: 80–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yan J, Wang B, Jiang Y, Cheng L, Wu T. GmFNSII-controlled soybean flavone metabolism responds to abiotic stresses and regulates plant salt tolerance. Plant Cell Physiol. 2014;55: 74–86. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pct159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Photographs were taken of cnotrol condition (A) and natural dry treatment (B). Water was provided to the well-watered control to maintain the volumetric soil moisture content (SMC) at 50–55%. For natural dry treatment, the 7-day-old seedlings were water withheld for 3 weeks, where the SMC was below 17%. At the end of treatment, the plant height and dry weight were measured. The relative plant height (C) and relative dry weight of shoots (D) were calculated as the ratio of the values under salt stress conditions to the value under control condition. P-values were calculated using Student’s t-test. *P < 0.05 compared with WT.

(TIFF)

Photographs were taken at the end of salt treatment of normal condition (A) and 200 mM NaCl treatment (B). The relative plant height (C) and relative dry weight of shoots (D) were calculated as the ratio of the values under salt stress conditions to the value under control condition. P-values were calculated using Student’s t-test. **P < 0.01 compared with WT.

(TIFF)

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.