Abstract

Objectives

Researchers have found a link between neighborhood risk factors and youth risk behaviors. However, the pathways by which this occurs remain poorly understood. This study sought to test a hypothesized pathway that suggests the influence of neighborhood risk on sexual risk and substance use among urban African American youth may operate indirectly via their psychological outlook about current and future opportunities.

Methods

Secondary data analysis using Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) was used to test the conceptual framework. The sample included 592 African American youth (61% female, 39% male) mean age 15.58 years, 1.23 SD. A modified structural equation model (SEM) met pre-specified global fit index criteria.

Results

The model contained three indirect paths linking increased neighborhood risk to increased sexual risk and substance use through higher levels of psychological outlook and youth approval of substance use.

Conclusions

These findings increase our understanding of factors that influence the initiation and progression of substance use and sexual risk behaviors among urban African American adolescents.

Keywords: Risk Behavior, African American youth, Neighborhood

African American youth face many challenges at multiple levels of influence that may increase their involvement in risk behaviors; including sexual behaviors that may place youth at risk for unintended pregnancy and STIs/HIV. African American youth are more than twice as likely to experience pregnancy as white youth (Bridges, 2011). In 2014, rates of STIs were highest among African American youth compared to youth of other racial groups (CDC, 2015). Specifically, the Chlamydia rate among African American females ages 15–19 years was almost five times the rate among white females in the same age group. Similarly, the rate of Chlamydia among African American males ages 15–19 years was nine times the rate among white males in the same age group. The rates observed for HIV/AIDS are just as disparate. In 2010, 57% of the diagnoses of HIV infection were among African American youth 13 to 24 years of age.(CDC, 2014a).

Decades of research focused on adolescent sexuality have identified behaviors that are related to negative health consequences (Kotchick et al. 2001). These include substance use before sexual activity, multiple/concurrent sexual partners, high numbers of lifetime sexual partners and early age of sexual debut. According to the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System (YRBSS), involvement in sexual risk behaviors is higher among African American youth compared with youth from other racial groups (CDC, 2014b). Data from YRBSS indicate that the prevalence of having had sexual intercourse before age 13 years was higher among African American (14.0%) compared to white (3.3%) and Hispanic (6.4%) students (CDC, 2014b). The prevalence of having had sexual intercourse with four or more partners was higher among African American students (26.1%) compared to their white (13.3%) and Hispanic (13.4%) peers. Although substance use among African American youth is lower than use among white and Latino youth (Johnston et al, 2006), there is evidence that African American youth who use drugs experience more negative consequences than their non-African American peers (Cooley-Strickland et al., 2009; Galea & Rudenstine, 2005; NIDA, 1995).

Our paper will examine the literature focused on the neighborhood environment and its impact on adolescent substance use and sexual risk behavior. This will be followed by a discussion of how individual perceptions/outlook are related to adolescent risk taking. We will then introduce a conceptual framework linking neighborhood environmental factors, individual perceptions/outlook and adolescent substance use and sexual risk taking among African American youth.

Neighborhood Factors and Youth Risk Behavior

As mentioned, multiple levels of influence may increase African American youth involvement in substance use and sexual risk behaviors; including those associated with community context (Browning, Leventhal, & Brooks-Gunn, 2004; Cohen et al., 2000; Farrell & Sullivan, 2004; Lambert et al., 2004; Sanders Phillips, 1997; Schier et al., 1999). For example, a study of African American males ages 13–19 years (Voisin, Hotton, Neilands, 2014) found that those who reported being victims of community violence were more likely to engage in sexual risk behaviors than those who were non-victims. In addition to experiencing community violence, neighborhood risk has also been characterized by high levels of daily hassles, considered to be frustrating, harmful, or threatening everyday experiences that are due to interactions between an individual and their neighborhood environment (Lazarus 1984). Previous studies have found a link between the experience of daily hassles and risk taking behavior among urban African American youth (DuBois, 2002; Grant et al., 2000; Waller, 2004). Although there are numerous studies highlighting the impact of neighborhood risk on substance use and sexual risk among urban African American youth, the mechanism by which this occurs is relatively understudied.

Social control, social capital and stress theories have been proposed to explain how neighborhood risk may impact youth substance use and sexual risk (Bourdieu, 1986; Catalano et al., 1996; Hirschi, 1969; Myers & Sanders Thompson, 2000; Putnam, 1993; Sampson, Morenoff, & Gannon-Rowley, (2002). Although these theoretical models are noteworthy, there may be additional pathways by which neighborhood risk influences youth substance use and sexual risk behaviors, particularly as it relates to urban African American youth. We argue that a more culturally and contextually relevant theory is needed that speaks to the lived experiences of urban African American youth. Studies have found that African American youth living in a community with high levels of neighborhood risk may feel confined in their situation, unable to control their circumstances and hopeless about their future prospects (Nebbitt, 2009; White, 2002). Thus it may be advantageous to examine these aspects of the young urban African American experience as it relates to substance use and sexual risk.

Hopelessness, Low Levels of Self-Efficacy and Risk Behavior

Hopelessness has been defined as the expectation that favorable outcomes for oneself are unlikely to occur, as well as negative expectations about one’s future (Kerpelman, Eryigit, Stephens, 2008; Joiner & Wagner, 1995; McLaughlin, Miller, & Warwick, 1996). Kagen et al. (2012) found that among African American adolescent males, hopelessness was significantly related to increased sexual risk. In addition, a longitudinal study of 1,774 adolescents found that participants reporting greater hopelessness in year one were more likely to identify with positive attitudes towards violence in year two (Drummond, Bolland, Harris, 2011). In addition to hopelessness, self-efficacy has been found to be associated with youth outcomes.

Perceived self-efficacy is an individual’s belief that they have control over their behavior and environment, and belief in their ability to produce a desired effect (Bandura, 1994). Previous research has found a link between low levels of perceived self-efficacy and increased substance use and sexual risk behaviors (Hays & Ellickson, 1990). For example, a study of 213 African American male adolescents found that self-efficacy was significantly negatively associated with attitudes towards risk taking (Nebbitt, 2009). In addition, Ross, Reynold and Geis (2000) found that individuals who lived in communities characterized by risk were less likely to perceive a sense of control over their lives.

We are proposing that feelings of hopelessness and low levels of self-efficacy indicate a particular psychological outlook that youth have about their current situation and future opportunities which may have relevance for substance use and sexual risk involvement. A qualitative study conducted with urban African American girls found that they expressed hopelessness due to their perception of having limited future opportunities (White, 2002). These young women also exhibited low self-efficacy through a perceived lack of control over factors in their current lives (White, 2002). In addition, the study described that these girls recognized mainstream avenues to opportunity may not be available to them. As they no longer aspired to conventional avenues of success, they became involved in substance use and sexual risk taking because the consequences of engaging in those behaviors were less paramount.

Youth Attitudes Toward Risk Behavior

Youth having favorable attitudes toward substance use and sexual risk taking is associated with their involvement in those behaviors (Kotchick et al., 2001). Although the relationship between neighborhood risk, youth attitudes and outcomes has been quantitatively examined in models of academic achievement among urban youth (Austin-Smith & Fryer, 2005; Fordham & Ogbu, 1986), this relationship has been relatively understudied. Educational researchers have proposed that the negative environmental conditions (e.g., living in high crime communities) often experienced by urban African American youth may lead to alternative lifestyles (e.g., street culture) that emphasize attitudes which are unconventional (e.g., normative to drop out of school) compared to mainstream standards espoused as traditional American values (e.g. using education to improve career success). We propose that this model may have relevance for informing our understanding of the pathway by which neighborhood context influences substance use and sexual risk behaviors among urban African American youth.

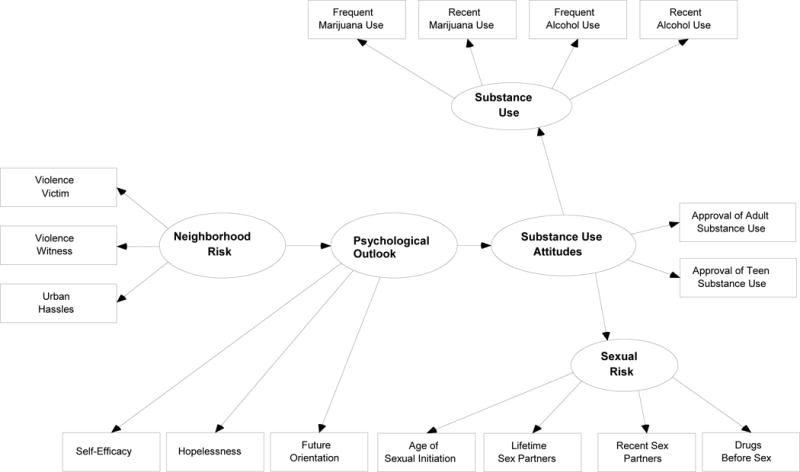

Our study examines the impact of neighborhood risk, defined as exposure to community violence and experience with urban hassles, on substance use and sexual risk behaviors among urban African American youth (see Figure 1). Based on the previous literature, we hypothesize that youth who perceive higher levels of neighborhood risk will be more likely to engage in substance use and sexual risk behaviors. In addition, neighborhood risk will be associated with substance use and sexual risk by way of youth psychological outlook (i.e. hopelessness and low levels of self-efficacy) and youth approval of substance use.

Figure 1.

Conceptual Model Depicting the Relationships of Neighborhood Risk, Sexual Risk, and Substance Use

Method

Data for the current study were drawn from an existing dataset that was previously conducted in 2004 and funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (third author, PI). The sample for the current study included 592 (61% female, 39% male) African American adolescents grades 9–12. The mean age of the sample was 15.58 years (1.23 SD). Youth were recruited from a single high school in a city on the mid-Atlantic coast. This high school serves approximately 1400 students, of whom 90% were African American. The high school is located in a low-income area. At the time of data collection in the neighborhood feeding the school, 30,000 children under 18 were classified as living in poverty, 40,000 students were eligible for free lunches and more than 11,000 were eligible for reduced lunch.

Procedure

In the larger study, a random sample of students, stratified by grade and gender, received packets that explained the purpose of the study and a consent form to be signed by a parent or legal guardian giving permission for the student to participate. Random selection of students continued until 80% of those approached (n = 1000) returned consent forms. Seventy-one percent of those who returned consent forms completed the survey (i.e., 71% of 800). After consent forms were returned, students were assigned to small groups of 10 (same gender) to complete the survey in classrooms. Prior to beginning the survey session, all students were reminded that their participation was voluntary and they were free to refuse to answer any questions. To avoid bias as a result of differences in reading abilities, the interviewers read each question and response choices aloud, while students followed along on their own questionnaires, privately marking their responses. All students were compensated ($20) for their participation.

Measures

All survey measures in the study were self-report and had been used in previous studies with urban African American youth.

Dependent Variables

Risk Behavior

All measures of the dependent variables in this study were items from the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance Survey -YRBSS (CDC, 2014b). The YRBSS was first administered in 1990 and has been widely used with youth of color Modifications of the questions on alcohol use, illegal drug use, and sexual risk behaviors were utilized in this study.

Substance Use

Substance use was measured by asking youth how often they used alcohol and marijuana (responses included no use, occasional use [once a month or less)], regular use [more that once a month], and daily). Recent drug use was measured by responses to how often youth used Alcohol and Marijuana in the past 30 days (never, once, twice, three or more times).

Sexual Risk

Participants were asked questions related to their sexual behaviors. Specifically they were asked, “How old were you when you had voluntary sex for the first time?” Responses were collapsed into three categories (0-never had sex, 1-less than 13 years, 2- older than 13 years). Participants were asked “How many people have you ever had sex with?” Responses were collapsed into three categories (0-never had sex, 1-one lifetime partner, 2- two-three lifetime partners, 3- four or more lifetime partners). Participants were asked, “During the past 3 months, with how many people did you have sex?” Responses were collapsed into three categories (0-never had sex, 1-one recent partner, 2- two-three recent partners, 3- four or more recent partners. Youth were also asked, “The last time you had sex, did you drink alcohol or use drugs before or during sex?” (0- never had sex, 1- yes, 2- no).

Independent Variables

Neighborhood Risk

Community Violence

The Survey of Exposure to Community Violence (Richters & Martinez, 1993) assesses exposure to 27 types of violence. This scale was developed using low income, ethnic minority sample and has been used in similar studies examining the impact of community violence on low-income ethnic minority adolescents (Berman et al., 1996; Fitzpatrick & Boldizar, 1993; Palmeri & Truscott, 2004). The survey is further subdivided into direct exposure (victim subscale) and indirect (witness subscale). The two scales had acceptable levels of internal consistency (reliability) as indicated by Cronbach’s alpha: .78 for the Victim scale and .86 for the Witness scale.

Community Violence Victim scale. This subscale assesses adolescent directly experience with acts of violence perpetrated against themselves. Sample questions include, “How many times have you yourself actually been attacked or stabbed with a knife?” and “How many times have you yourself been slapped or punched or hit by someone?” Each question asks how many times the event has occurred (never, once or twice, a few times, many times). Items are scored so that higher scores represent greater levels of victimization due to community violence (Min 11– Max 44).

Community Violence Witness subscale. This subscale assesses adolescents who have seen or heard about various acts of violence in their community. Sample items include, “How many times have you seen someone else getting beaten up or mugged?” and “How many times have you heard the sound of gunfire outside when you were in or near the home?” Each question asks how many times the event has occurred (never, once or twice, a few times, many times). Items are scored so that higher scores represent greater levels of witnessing community violence (Min 15– Max 60).

Urban Hassles

The Urban Hassles Scale-UHS measures the stress that reflects daily stressors in an urban setting (Miller, Webster & MacIntosh, 2002). Development of the UHS was based on David Miller’s work experience and previous research with adolescents living in urban environments. The UHS is a 9-item measure where respondents are asked to indicate on a Likert-type scale ranging from 0 (none at all) to 2 (a lot) whether they experienced certain hassles. For example, “How often in the last two weeks have you been asked for money by drug addicts?” Items on the scale were summed for a score between 0 and 18. Cronbach’s alpha for the scale = .88.

Youth Psychological Outlook

Hopelessness

Hopelessness was measured by a 6-item scale Brief Hopelessness Scale (Bolland, 2003). Sample items include, “I might as well give up because I can’t make things better for myself” and “I do not think that I will live a very long life.” The items are scored either “agree” (1) or “disagree” (0) with a Cronbach alpha of .72 for this sample.

Future Orientation

Future orientation was measured by asking participants to respond to one true/false statement: ”I believe that young people who grow up in my neighborhood can be anything they want to be.”

Self-Efficacy

The Generalized Perceived Self-Efficacy scale was used to measure a broad and stable sense of personal competence to deal efficiently with a variety of stressful situations (Schwarzer, Mueller, Greenglass, E., 1999). For example, “If I am in trouble, I can think of a good solution” and “Thanks to my abilities I can handle unexpected situations.” The response categories ranged from not true at all (1) to true all of the time (4). This 10-item measure has been used across a range of populations, including adults and high school students. Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was .90.

Youth Attitudes Towards Substance Use

Youth attitudes toward substances were assessed by asking respondents whether they approved of adult and teen substance use (alcohol, tobacco, marijuana, cocaine, other illegal drugs). Respondent answer options were yes vs. no. Cronbach’s alpha for attitudes toward adult drug use was .74; the alpha for attitudes toward teen drug use was .73.

Data Analysis

We used structural equation modeling (SEM) to evaluate the direct, indirect, and total associations of neighborhood risk with sexual risk behavior. Based on the literature, theory, and available measures described above, we designed an initial structural equation model in which a latent variable capturing neighborhood risk (being a victim of community violence, witnessing community violence, experiencing urban hassles) was linked to youth psychological outlook (self-efficacy, hopelessness, future orientation). Youth psychological outlook in turn explained youth attitudes towards substance use.

Youth substance use attitudes explained sexual risk behavior (age of sexual initiation, number of lifetime sexual partners, number of recent sex partners, substance use before sex) and substance use (frequency of marijuana use, recent marijuana use, frequency of alcohol use, and recent alcohol use). Self-identified gender (male vs. female) and participant age in years were treated as covariates of the aforementioned latent variables. This conceptual model is shown in Figure 1.

Based on the conceptual model, we specified an initial structural equation model that contained the relationships depicted in Figure 1, as well as the regression of youth psychological outlook, attitudes towards substance use, sexual risk and substance use onto the age and gender covariates. This model also contained direct effects linking neighborhood risk, youth psychological outlook, and youth attitudes to sexual risk and substance use. Finally, the model allowed the residual variances of the substance use and sexual risk latent factors to correlate.

Model Estimation and Evaluation of Model Fit

We used a weighted least-squares (WLSMV) estimator available in Mplus 7.4 to estimate parameters, standard errors, and test statistics (Flora & Curran, 2004). Exact model-data fit was evaluated via the chi-square test of exact fit. Approximate model-data fit was evaluated using the following well-studied descriptive measures of model fit: the Comparative Fit Index (CFI) (Bentler & Bonnett, 1980) and the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSE)(Browne & Cudek, 1993). CFI values of .95 or larger and RMSEA values of .06 or lower indicate satisfactory approximate model fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999). If the initially-specified model did not meet the desired cutoff values, modification indices (MI) were generated and a limited number of theoretically-consistent model modifications were adopted until the model attained satisfactory fit to the data. To compute optimal standard errors and confidence limits for indirect effects, we employed the bias-corrected bootstrap (MacKinnon, Lockwood, & Williams, 2004; Shrout & Bolger, 2002), with the number of bootstrap samples set above 5000 to insure sufficient precision of the confidence intervals Hox (2002). For each estimated parameter, we report its unstandardized estimate, 95% confidence limits, and the standardized parameter estimate.

Results

Descriptive Results

Almost half of the sample (44%) reported they had never had sexual intercourse. However, many of the youth did participate in behaviors that may place them at risk for negative health outcomes (including STIs, unintended pregnancy). Of those who had initiated sexual activity, 24% had sexual intercourse before the age of 13. The majority of youth who had initiated sexual activity (69%) had 2 or more sexual partners in their lifetime and almost 20% reported sexual intercourse with two or more partners within the past 3 months. Six percent of participants who had initiated sexual activity reported using alcohol or drugs the last time they had sex. Some students reported regular (more than once a month) or every day use of alcohol (8%) and marijuana (9%). Youth also reported recent drug use including using alcohol (13%) and marijuana (13%) three or more times in the past 30 days. Table 1. lists frequencies of dependent variables by gender.

Table 1.

Sexual Risk Frequencies by Gender (n= 592)

| Ever Had Sex | Male | Female | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Never had sex | 11.90% | 33.20% | 45.10% |

| Had sex, but not in last 3 months | 4.80% | 12.10% | 16.90% |

| One sex partner, last 3 months | 9.10% | 11.10% | 20.10% |

| Two or three sex partners, last 3 months | 11.80% | 6.10% | 17.80% |

| Total | 37.60% | 62.40% | 100.00% |

|

| |||

| Early Sexual Initiation | |||

|

| |||

| Never had sex | 11.60% | 32.10% | 43.70% |

| Had sex after age 13 | 11.60% | 20.80% | 32.40% |

| Had sex before age 13 | 15.60% | 8.30% | 23.90% |

| Total | 38.80% | 61.20% | 100.00% |

|

| |||

| Currently Sexually Active | |||

|

| |||

| Never had sex | 11.80% | 32.90% | 44.70% |

| Had sex, but not in last 3 months | 8.50% | 8.10% | 16.60% |

| One sex partner, last 3 months | 10.10% | 17.80% | 27.90% |

| Two or three sex partners, last 3 months | 4.80% | 2.70% | 7.40% |

| Four or more sex partners, last 3 months | 3.00% | 0.40% | 3.40% |

| Total | 38.20% | 61.80% | 100.00% |

|

| |||

| Alcohol Use Before Sex | |||

|

| |||

| Never had sex | 11.20% | 31.50% | 42.70% |

| Had sex, but no alcohol with sex | 24.20% | 26.80% | 51.00% |

| Had sex and alcohol with sex | 3.60% | 2.60% | 6.20% |

| Total | 39.10% | 60.90% | 100.00% |

|

| |||

| Alcohol use, past 30 days | |||

|

| |||

| 0 times | 28.20% | 44.40% | 72.60% |

| 1 or 2 times | 6.70% | 9.10% | 15.70% |

| 3 to 9 times | 3.60% | 4.60% | 8.20% |

| 10 to 19 times | 0.90% | 2.60% | 3.40% |

| Total | 39.30% | 60.70% | 100.00% |

|

| |||

| Frequency of Alcohol use | |||

|

| |||

| I don’t use | 24.10% | 36.80% | 60.90% |

| I occasionally use | 12.10% | 19.50% | 31.60% |

| I regularly use | 2.90% | 4.40% | 7.40% |

| I use every day | 0.20% | 0.00% | 0.20% |

| Total | 39.30% | 60.70% | 100.00% |

|

| |||

| Marijuana use, past 30 days | |||

|

| |||

| 0 times | 28.40% | 48.60% | 77.10% |

| 1 or 2 times | 5.30% | 6.40% | 11.70% |

| 3 to 9 times | 2.90% | 2.80% | 5.70% |

| 10 to 19 times | 2.90% | 2.60% | 5.50% |

| Total | 39.70% | 60.30% | 100.00% |

|

| |||

| Frequency of marijuana use | |||

|

| |||

| I don’t use | 27.40% | 46.40% | 73.80% |

| I occasionally use | 7.10% | 10.10% | 17.20% |

| I regularly use | 3.30% | 3.30% | 6.60% |

| I use every day | 1.60% | 0.90% | 2.40% |

| Total | 39.30% | 60.70% | 100.00% |

The neighborhood risk scales were the predictor variables of interest in this study. Across gender, the mean score on the scale assessing youth experience with witnessing community violence was 31.79 (SD=8.15, Range 15–58). Indicating an overall moderate frequency of witnessing violence among the sample (e.g., a few times). Students in our sample listed the following experiences of witnessing violence ‘many times’, 1- seen other people using or selling drugs (61%), 2- hearing the sounds of gunfire outside when they were in or near their home (60%), and 3- heard about someone being killed by another person (46%). The mean for the scale assessing youth experience with community violence was 15.92 (SD=4.54, Range 11–44) indicating moderate level of experience being a victim of violence (e.g., one or two times). Youth were most likely to report 1- being slapped, punched or hit by someone (20%), 2- being asked to get involved in any aspect of selling or distributing illegal drugs (10%), and 3- being threatened with serious physical harm by someone (8%).

The mean score for urban hassles was 18.96 (SD=12.70, Range 0–74), indicating a relatively low level of hassles among youth. The hassles listed the most by youth were 1- worrying about the safety of family members (31%) and 2- worrying about their own safety (33%). Table 2 provides means and standard deviations for all independent variables by gender.

Table 2.

Frequencies of Independent Variables by Gender (N=592)

| Variable | Male | Female | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| Witness Violence | 32.60 | 8.61 | 31.27 | 7.81 | 31.79 | 8.15 |

| Victim Violence | 17.08 | 5.22 | 15.18 | 3.89 | 15.92 | 4.54 |

| Hopelessness | 0.86 | 1.39 | 0.51 | 1.03 | 0.65 | 1.19 |

| Self Efficacy | 25.84 | 7.03 | 27.15 | 6.47 | 26.62 | 6.72 |

| Urban Hassles | 19.47 | 13.44 | 18.64 | 12.22 | 18.96 | 12.70 |

| Future Drug Use | 0.43 | 0.91 | 0.30 | 0.60 | 0.35 | 0.74 |

| Attitude Adult Use | 1.20 | 1.44 | 1.20 | 1.38 | 1.198 | 1.40 |

| Attitude Youth Use | 0.6277 | 1.14205 | 0.5899 | 1.06165 | 0.6048 | 1.09319 |

Structural Equation Models

The fit of the initial structural equation model, χ2 (N = 592; DF = 119) = 546.24, p < .0001; CFI = .98, and RMSEA = .08, suggested a lack of fully satisfactory fit. Modifying the model to include residual correlations of marijuana frequency and recent marijuana use (MI = 130.65) and alcohol frequency and recent alcohol use (MI = 133.98) improved model-data fit and the revised model met the target model fit criteria: χ2 (N = 592; DF = 117) = 378.55, p < .0001; CFI = .99, and RMSEA = .06. Table 3 displays the revised model’s unstandardized direct effects and 95% confidence intervals.

Table 3.

Unstandardized Regression Weights (B) and 95% Confidence Intervals (CI) from the Final Structural Equation Modela

| Outcome | Explanatory | B | CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Community Violence Victim | Neighborhood Risk | 1.00 | (1.00, 1.00) |

| Community Violence Witness | Neighborhood Risk | 0.75 | (0.65, 0.92)** |

| Experiences of Urban Hassles | Neighborhood Risk | 0.92 | (0.76, 1.11)** |

| Self-Efficacy | Psychological Outlook | 1.00 | (1.00, 1.00) |

| Hopelessness | Psychological Outlook | 2.39 | (0.23, 3.95)** |

| Future Orientation | Psychological Outlook | −1.19 | (−3.01, 1.23) |

| Teen Substance Use Approval | Substance Use Attitudes | 1.00 | (1.00, 1.00) |

| Adult Substance Use Approval | Substance Use Attitudes | 1.27 | (1.10, 1.54)** |

| Age of Sexual Initiation | Sexual Risk | 1.00 | (1.00, 1.00) |

| Number of Lifetime Sex Partners | Sexual Risk | 1.05 | (1.02, 1.08)** |

| Number of Recent Sex Partners | Sexual Risk | 0.99 | (0.95, 1.02)** |

| Use of Drugs Before Sex | Sexual Risk | 1.03 | (1.00, 1.07)** |

| Frequent Alcohol Use | Substance Use | 1.00 | (1.00, 1.00) |

| Recent Alcohol Use | Substance Use | 1.03 | (0.94, 1.12)** |

| Frequent Marijuana Use | Substance Use | 1.10 | (0.97, 1.28)** |

| Recent Marijuana Use | Substance Use | 1.07 | (0.93, 1.27)** |

| Psychological Outlook | Neighborhood Risk | 0.04 | (0.02, 0.10)** |

| Psychological Outlook | Age | 0.02 | (0.00, 0.13) |

| Psychological Outlook | Gender | −0.07 | (−0.17, −0.03)** |

| Substance Use Attitudes | Neighborhood Risk | −0.03 | (−0.84, 0.09) |

| Substance Use Attitudes | Psychological Outlook | 4.60 | (3.12, 12.80)** |

| Substance Use Attitudes | Age | −0.14 | (−2.01, −0.04)** |

| Substance Use Attitudes | Gender | 0.29 | (0.10, 1.10)** |

| Sexual Risk | Neighborhood Risk | 0.11 | (−0.20, 0.19) |

| Sexual Risk | Psychological Outlook | 2.08 | (−0.25, 8.04) |

| Sexual Risk | Substance Use Attitudes | 0.14 | (−0.59, 0.29) |

| Sexual Risk | Age | 0.11 | (−0.36, 0.19) |

| Sexual Risk | Gender | −0.45 | (−0.64, 0.36) |

| Substance Use | Neighborhood Risk | 0.08 | (−0.20, 0.14) |

| Substance Use | Psychological Outlook | 2.19 | (0.38, 7.57)* |

| Substance Use | Substance Use Attitudes | 0.35 | (−0.35, 0.49) |

| Substance Use | Age | 0.01 | (−0.44, 0.07) |

| Substance Use | Gender | 0.05 | (−0.11, 0.74) |

Notes: N = 592 respondents. Outcome refers to mediating or dependent variables in the structural equation model; Explanatory refers to explanatory or independent variables in the structural equation model. 95% confidence intervals are bias-corrected and originate from 5,318 bootstrap samples.

95% confidence interval does not include zero, signifying statistical significance at p < .05.

99% confidence interval does not include zero, signifying statistical significance at p < .01. The residual covariance of frequent alcohol use with recent alcohol use was r = 0.27 (95% CI = 0.17, 0.38), p < .01; the residual covariance of frequent marijuana use with recent marijuana use was r = .28 (95% CI = 0.16, 0.38), p < .01. The residual covariance of sexual risk and substance use was r = 0.12 (95% CI = −0.07, 0.19), ns.

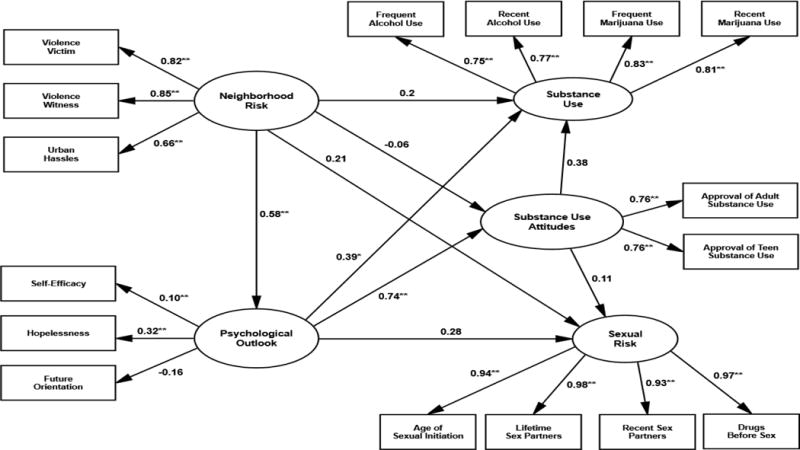

The model contains three indirect paths linking the latent neighborhood risk variable to the latent sexual risk variable (See Figure 2). The first indirect path connects neighborhood risk to sexual risk via psychological outlook. This effect was positive and statistically significant (B = .09, 95% CI = .01, .44; β = .16), indicating that increased sexual risk was associated with increases in neighborhood risk via psychological outlook. The second indirect path connects neighborhood risk to sexual risk via attitudes towards substance use. This effect was not statistically significant (B = −.004, 95% CI = −.57, .003; β = −.01). The third indirect path connects neighborhood risk to sexual risk by psychological outlook and attitudes towards substance use. This effect was positive and statistically significant (B = .03, 95% CI = .01, .42; β = .05), indicating that increases in neighborhood risk levels are associated with increases in sexual risk via psychological outlook and attitudes towards substance use, as hypothesized by the theoretical model depicted in Figure 1. The total indirect effect of neighborhood risk to sexual risk was significant (B = .11, 95% CI = .05, .43; β = .20) as was the total overall effect that is the sum of the direct and indirect effects (B = .23, 95% CI = .18, .28; β = .41). Taken collectively, these results indicate that neighborhood risk is associated with sexual risk through psychological outlook and psychological outlook via attitudes towards substance use, but not through attitudes towards substance use alone.

Figure 2.

Structural Equation Model of Neighborhood Risk, Sexual Risk, and Substance Use (Standardized Coefficients, N=592)

*p < .05; **p < .01

r for frequent alcohol use and recent alcohol use = .65, p < .01

r for frequent marijuana use and recent marijuna use = .83, p < .01

r for substance use with sexual risk – .35, NS

A similar set of three indirect effects were computed linking the latent neighborhood risk variable to the latent substance use variable. The first indirect path connects neighborhood risk to substance use via psychological outlook. This effect was positive and statistically significant (B = .09, 95% CI = .02, .43; β = .23), indicating that increased substance use was associated with increases in neighborhood risk via psychological outlook. The second indirect path connecting neighborhood risk to substance use via attitudes towards substance use was not statistically significant (B = −.01, 95% CI = −.59, .03; β = −.02). The third indirect path connects neighborhood risk to sexual risk by psychological outlook and attitudes towards substance use. This effect was positive and statistically significant (B = .07, 95% CI = .03, .79; β = .17), indicating that increases in neighborhood risk levels are associated with increases in substance use mediated by psychological outlook and psychological outlook and attitudes towards substance use together, which is consistent with the theoretical model shown in Figure 1. The total indirect effect of neighborhood risk to substance use was significant (B = .15, 95% CI = .10, .43; β = .37) as was the total overall effect (B = .23, 95% CI = .19, .29; β = .56).

Age and Gender

The impact of age and gender covariates on the latent variables in the model was limited. Results indicated a negative gender effect on psychological outlook, in that males were higher on negative psychological outlook than females. In addition, there was a positive effect of gender on attitudes towards substance use, indicating that females exhibited less positive attitudes towards substance use than males. There was also a negative effect of age on attitudes towards substance use such that increases in age were associated with less positive attitudes towards substances.

Discussion

As has been documented in many studies of urban African American youth, participants in our study also reported having personal experience with community violence including victimization through physical violence, as well as witnessing violence and rampant drug activity (Browning, Leventhal, & Brooks-Gunn, 2004; Lambert et al., 2004; Voisin, Hotton, Neilands, 2014). They listed experiences with urban hassles at similar levels to those reported from previous research with urban African American youth (DuBois, 2002; Grant et al., 2000; Waller, 2004).

Many youth in our sample had high levels of hopelessness, low self-efficacy and a negative outlook on their current situation and/or future. Given the focus on youth in our study, we felt it was important to investigate both proximal and distal notions of ‘outlook.’ Taking future planning into account can be developmentally challenging for youth, as abstract thinking forms in late adolescence. Therefore, these measures of psychological outlook examined both current and future perceptions of how well youth are/will be able to navigate life. Our research is a first step in quantitatively examining the behavioral outcomes associated with having a negative psychological outlook. This is in line with findings from several interview studies which have documented that negative outlook can be a consequence of youth living in distressed neighborhood environments (White, 2002). Future research could examine whether future or current expectations are more or less explanatory.

We presented a new framework for understanding how neighborhood environment may impact sexual risk and substance use among urban African American youth, with increased cultural and contextual relevance for this population. Through this proposed pathway, the absence of direct effects coupled with the presence of statistically significant indirect effects implies that psychological outlook and youth approval of substance use mediate the relationship between neighborhood risk and sexual risk/substance use (Fritz, Cox, & MacKinnon, 2014; MacKinnon, 2008; O’Rourke & MacKinnon, 2015). These findings are similar to other studies that have identified an indirect effect of hopelessness on other youth outcomes (Gonzalez et al., 2012). Taken together, our findings and the previous literature indicate that it is not negative community experience alone that is associated with youth risk behavior. Rather, our research suggests that neighborhood violence coupled with a negative outlook on one’s current and/or future prospects are associated with youth involvement in risk taking. It is possible that a young person’s outlook on life is impacted by experiencing violence, leading them to turn to substance use and sexual risk as a way to cope the pain of these experiences. It is also possible that a negative psychological outlook could encourage youth to reject mainstream goals (e.g., obtaining conventional employment). Without these goals in place, youth have fewer tangible consequences for engaging in substance use and sexual risk taking. This model is similar to that found in educational achievement studies with African American youth (Austin-Smith & Fryer, 2005; Fordham & Ogbu, 1986).

It is useful to consider the findings of this study within a historical and contemporary context. For example, psychological outlook is a construct associated with the marginalized experiences of African American youth living in distressed environments. Marginalization is a term that has been used to describe the experiences of African American and other populations of color. Marginalization has been defined as being isolated from or not fully integrated into mainstream society (Leonard, 1984). Marginalization can occur for a number of reasons including belonging to a marginalized group (Burton & Kagan, 2003). Given the subordinate social status in which African Americans are placed in society, many African American youth may feel marginalized. Marginalization may also be a result of living in socially isolated or deprived environments (Burton & Kagan, 2003). A disproportionate number of African American youth live in neighborhoods that are economically and socially isolated from mainstream society (McKinnon & Bennett, 2005; McLoyd, 1998; U.S. Census, 2000). Therefore, marginalization due to location may also be a factor of relevance for urban African American youth. Previous qualitative studies have identified psychological outlook, by virtue of feeling hopeless and not in control of one’s life, as key aspects contributing to individual’s experience of marginalization (Anderson, 1999; Martin-Baro, 1996; Young Jr., 2004). Despite this, marginalization as a construct has received limited attention in the psychological literature. Given the cultural relevance of this factor, future studies should be developed to quantitatively examine youth experiences of marginalization and how it relates to psychological outlook and behavioral outcomes (e.g., sexual risk, substance use, violence).

The gender effects observed in this study suggest that males had higher levels of hopelessness and youth approval of substance use, both of which contributed to their sexual risk. Therefore, gender specific approaches may be useful in developing tailored models of sexual risk. Future studies could describe the various domains of hopelessness that are more prevalent among males. For example, do ideals of masculinity, including issues of power and financial security, contribute to high levels of hopelessness in employment specific domains? How does hopelessness across domains impact sexual risk and other youth risk behaviors?

Although many of our participants engaged in sexual risk and drug use behaviors, the majority did not. What are the differences between these youth? Despite living in communities with similar levels of distress, there appears to be some resiliency factors that serve as a buffer to involvement in risk behaviors. Studies that focus on youth not engaged in risk behaviors could add to the literature about pathways of success among urban at risk African American youth. Additionally, we know that protective neighborhood factors have an impact on youth development (Aisenburg & Herrenkohl, 2008; Browning, Leventhal, & Brooks-Gunn, 2004). Future studies could expand the conceptual model to include protective neighborhood factors (e.g., neighborhood resources, community cohesion).

Limitations

There are several limitations to the study design including the use of self-report measures, which may increase the chances of an individual over-reporting or under-reporting risk behaviors. To account for this, the survey was based on standardized measures that have been used in previous studies with similar populations. Youth were asked to comment on their own experiences with violence. This may not entirely reflect the amount of violence risk within the neighborhoods that they reside. The use of objective data (e.g. census tracts and police records) to measure neighborhood risk may have enhanced our findings. However, previous research has found that youth perceptions of neighborhood are significantly related to objective data (Plunkett et al., 2007). As community factors are also experienced at the individual level, we believe that understanding how youth personally experience violence has value, particularly as it relates to cognitive and behavioral outcomes.

Additionally, the measure of the independent variable psychological outlook was limited. Our study chose to focus on measuring psychological outlook as hopelessness, low self-efficacy and future orientation based on previous qualitative studies with this population (Anderson, 1999; Martin-Baro, 1996; Young Jr., 2004). There are other factors that may be related to psychological outlook, such as mental health. Despite the limited focus, we believe our study was a first step in identifying variables of merit for this construct.

The sample included youth who attend a public high school that may be a different from the general youth population. However, the youth reside in neighborhoods with high levels of risk, which may place them in similar contextual environments after school as those attending other public high schools in the area. Another limitation of the study is that the research was conducted in one geographic location. We chose this location because of its high HIV/STI prevalence.

Furthermore, although we were able to report effects adjusted for gender and age, this secondary dataset did not have a sample large enough to permit fitting and testing separate models for males and females and across different age groups. Because both gender and developmental stage may lead to different experiences and psychological outlook over time, future studies should consider recruiting larger numbers of participants of both genders across various age ranges to identify variations in the model based on these demographic characteristics.

Finally, an important limitation of our study is the use of cross-sectional data. Cross-sectional data strongly limit drawing causal inferences, and this phenomenon is especially acute in analyses involving mediators because substitution of mediators for outcomes and vice versa may lead to equivalent structural equation models (Thoemmes, 2015). There is a growing recognition that longitudinal data are needed to obtain accurate causal inferences, including for analyses involving mediation (Mitchell & Maxwell, 2013). Despite the limitations, we believe this study and it’s findings have value as one of the first to propose and test a conceptual framework looking at psychological outlook as it relates to neighborhood risk and sexual risk among urban African American youth.

Conclusion

Our findings have implications for both policy and interventions. The results indicate that negative experiences of community violence and urban hassles have an impact on sexual risk and substance use involvement among urban African American youth by way of their psychological outlook. This calls for social policies that are aimed at improving the conditions of urban communities (i.e., improving resources; job opportunities), as well as structural violence prevention programs. Although new policy solutions may have the most impact, they should not be made in isolation of micro level interventions. As our findings show, there is variability in youth appraisals of their environment, which is significantly related to their risk involvement. Thus, interventions should be developed to improve psychological outlook and discourage youth approval of substances among youth living in distressed neighborhoods. Providing youth with a sense of empowerment in their current circumstances and a reason to feel more optimistic about their futures may be a prevention approach that is culturally and contextually relevant for urban African American youth (Clark et al., 2005).

Contributor Information

Scyatta A. Wallace, St. John’s University, Work conducted while first author at SUNY Downstate Medical Center.

Torsten B. Neilands, University of California at San Francisco

Kathy Sanders Phillips, Howard University

References

- Aisenberg E, Herrenkohl T. Community violence in context: risk and resilience in children and families. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2008;23(3):296–315. doi: 10.1177/0886260507312287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson E. Code of the Streets: Decency, violence, and the moral life of the inner city. New York: Norton & Co; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Austin-Smith D, Fryer RG., Jr An economic analysis of “Acting White”. Quarterly Journal of Economics. 2005;120(2):551–583. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Self-Efficacy. In: Ramachaudran VS, editor. Encyclopedia of human behavior. Vol. 4. New York, NY: Academic Press; 1994. pp. 71–81. [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM, Bonnett DG. Significance tests and goodness of fit in the analysis of covariance structures. Psychological Bulletin. 1980;88:588–606. [Google Scholar]

- Berman SL, Kurtines WM, Silverman WK, Serafini LT. The impact of exposure to crime and violence on urban youth. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1996;66(3):329–336. doi: 10.1037/h0080183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolland JM. Hopelessness and risk behaviour among adolescents living in high poverty inner-city neighbourhoods. Journal of Adolescence. 2003;26:145–158. doi: 10.1016/s0140-1971(02)00136-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu P. The forms of capital. In: Richardson JG, editor. The handbook of theory: Research for the sociology of education. New York: Greenwood Press; 1986. pp. 214–258. [Google Scholar]

- Bridges E. Unintended pregnancy among young people in the United States: Dismantling structural barriers to prevention. Washington, DC: Advocates for Youth; 2011. Accessed December 8th, 2015 http://www.advocatesforyouth.org/storage/advfy/documents/unintended%20pregnancy_5.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Browne MW, Cudek R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In: Bollen KA, Long JS, editors. Testing Structural Equation Models. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications; 1993. pp. 136–162. [Google Scholar]

- Browning CR, Leventhal T, Brooks-Gunn J. Neighborhood context and racial differences in early adolescent sexual activity. Demography. 2004;41(4):697–720. doi: 10.1353/dem.2004.0029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burton M, Kagan C. Marginalization. In: Prillenltensky I, Nelson G, editors. Community Psychology: In pursuit of wellness and liberation. New York: Palgrave MacMillan; 2003. pp. 293–308. [Google Scholar]

- Catalano RF, Kosterman R, Hawkins DL, Newcomb MD, Abbot R. Modeling etiology of adolescent substance use: a test of the social development model. Journal of Drug Issues. 1996;26:429–455. doi: 10.1177/002204269602600207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance 2014. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV among youth. 2014a Fact Sheet accessed online March 2nd, 2015 http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/risk_youth_fact_sheet_final.pdf.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Youth risk behavior surveillance- United States, 2013. MMWR. 2014b;63(4):1–169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark LF, Miller KM, Nagy SS, Avery J, Roth DL, Liddon N, Mukherjee S. Adult identity mentoring: reducing sexual risk for African American seventh grade students. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2005;37(4):337e1–337e10. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen DA, Spear S, Scribner R, Kissinger P, Mason K, Wildgen J. ‘Broken windows’ and the risk of gonorrhea. American Journal of Public Health. 2000;90:230–236. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.2.230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooley-Strickland M, Quille TJ, Griffin RS, Stuart EA, Bradshaw CP, Furr-Holden D. Community violence and youth: Affect, behavior, substance use, and academics. Clinical Child Family Psychology Review. 2009;12:127–156. doi: 10.1007/s10567-009-0051-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummond H, Bolland JM, Harris WA. Becoming violent: Evaluating the mediating effect of hopelessness on the code of the street thesis. Deviant Behavior. 2011;32:191–223. [Google Scholar]

- DuBois DL, Burk-Braxton C, Swenson LP, Tevendale HD, Hardesty JL. Race and gender influences on adjustment in early adolescence: investigation of an integrative model. Child Development. 2002;73(5):1573–1592. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrell AD, Sullivan TN. Impact of witnessing violence on growth curves for problem behaviors among early adolescents in urban and rural settings. Journal of Community Psychology. 2004;32(5):505–535. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick KM, Boldizar JP. The prevalence and consequences of exposure to violence among African American youth. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1993;32(2):424–430. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199303000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flora DB, Curran PJ. An empirical evaluation of alternative methods of estimation for confirmatory factor analysis with ordinal data. Psychological Methods. 2004;9(4):466–491. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.9.4.466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fordham S, Ogbu J. Black students’ school success: Coping with the “Burden of Acting White”. The Urban Review. 1986;18:176–206. [Google Scholar]

- Fritz MS, Cox MG, MacKinnon DP. Increasing statistical power in mediation models without increasing sample size. Evaluation & the Health Professions. 2015;38(3):343–366. doi: 10.1177/0163278713514250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galea S, Rudenstine S. Challenges in understanding disparities in drug use and its consequences. Journal of Urban Health. 2005;82(SS3):iii5–iii12. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jti059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez M, Jones DL, Kincaid CY, Cueller J. Neighborhood context and aduljustment in African American youth for single mother homes: The intervening role of hopelessness. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2012;18(2):109–117. doi: 10.1037/a0026846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant KE, O’Koon JH, Davis TH, Roache NA, Poindexter LM, Armstrong ML, et al. Protective factors affecting low income urban African American youth exposed to stress. Journal of Early Adolescence. 2000;20(4):388–417. [Google Scholar]

- Hays R, Ellickson P. How generalizable are adolescent beliefs about pro-drug pressures and resistance self-efficacy? Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1990;20(4):321–340. [Google Scholar]

- Hirschi T. Causes of delinquency. Berkeley: University of California Press; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Hox J. Multilevel analysis techniques and applications. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6(1):1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Demographic subgroup trends for various licit and illicit drugs, 1975–2005. Ann Arbor, MI: Institute for Social Research; 2006. p. 416. (Monitoring the Future Occasional Paper No 63). [Google Scholar]

- Joiner TE, Wagner KD. Attributional style and depression in children and adolescences. A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review. 1995;15:777–798. [Google Scholar]

- Kagen S, Deardorff J, McCright J, Lightfoot M, Lahiff M, Lippman SA. Hopelessness and sexual risk behavior among African American males in a low-income urban community. American Journal of Men’s Health. 2012;6(5):395–399. doi: 10.1177/1557988312439407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerpelman JL, Eryigit S, Stephens CJ. African American Adolescents’ Future Education Orientation: Associations with self-efficacy, ethnic identity and perceived parental support. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2008;37:997–1008. [Google Scholar]

- Kotchick BA, Shaffer S, Forehand R, Miller KS. Adolescent sexual risk behavior: A multi-system perspective. Clinical Psychology Review. 2001;21(4):495–519. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(99)00070-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert SF, Brown TL, Phillips CM, Ialongo NS. The relationship between perceptions of neighborhood characteristics and substance use among urban Black American adolescents. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2004;34(3/4):205–218. doi: 10.1007/s10464-004-7415-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RS. Puzzles in the study of daily hassles. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 1984;7:375–389. doi: 10.1007/BF00845271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard G. Personality and ideology: Towards a materialistic understanding of the individual. London, England: Macmillan; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Williams J. Confidence Limits for the Indirect Effect: Distribution of the Product and Resampling Methods. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2004;39(1):99–128. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr3901_4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Baro L. The lazy Latino: The ideological nature of Latin American fatalism. In: Aron A, Corne S, editors. Writings for a liberation psychology. New York: Harvard University Press; 1996. pp. 135–162. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP. Introduction to statistical mediation analysis. New York, NY: Erlbaum; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- McKinnon JD, Bennett CE. We the people: Blacks in the United States. Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin J, Miller P, Warwick H. Deliberate self-harm in adolescents: Hopelessness, depression, problems, and problem-solving. Journal of Adolescence. 1996;19:523–532. doi: 10.1006/jado.1996.0051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLoyd V. The impact of economic hardship on Black families and children: Psychological distress, parenting, and socioemotional development. Child Development. 1998;61:311–346. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1990.tb02781.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller DB, Webster SE, MacIntosh R. What’s there and what’s not: Measuring daily hassles in urban African American adolescents. Research on Social Work Practice. 2002;12(3):375–388. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell M, Maxwell SE. A comparison of the cross-sectional and sequential designs when assessing longitudinal mediation. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2013;48(3):301–339. doi: 10.1080/00273171.2013.784696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers MA, Sanders Thompson VL. The impact of violence exposure on African American youth in context. Youth and Society. 2000;32(2):253–267. [Google Scholar]

- National Institutes on Drug Abuse. Drug use among racial/ethnic minorities, revised. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS); 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Nebbitt V. Self-efficacy in African American males living in urban public housing. Journal of Black Psychology. 2009;35(3):295–316. [Google Scholar]

- O’Rourke HP, MacKinnon DP. When the test of mediation is more powerful than the test of the total effect. Behavioral Research Methods. 2015;47(2):424–442. doi: 10.3758/s13428-014-0481-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmeri SD, Truscott SD. Empathy, Exposure to Community Violence, and Use of Violence Among Urban, At-Risk Adolescents. Child and Youth Care Forum. 2004;33(1):33–50. [Google Scholar]

- Plunkett SW, Abarca-Mortensen S, Behnke AO, Sands T. Neighborhood structural qualities, adolescent perceptions of neighborhoods and Latino youth development. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2007;29(1):19–34. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam RD. The prosperous community: Social capital and public life. American Prospect. 1993;13:35–42. [Google Scholar]

- Richters JE, Martinez P. The NIMH community violence project: I. Children as victims of and witnesses to violence. Psychiatry. 1993;56:7–21. doi: 10.1080/00332747.1993.11024617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross CE, Reynolds JR, Geis KJ. The contingent meaning of neighborhood stability for residents’ psychological well-being. American Sociological Review. 2000;65:581–597. [Google Scholar]

- Sampson RJ, Morenoff JD, Gannon-Rowley T. Assessing “neighborhood effects”: social processes and new directions in research. Annual Review of Sociology. 2002;28:443–478. [Google Scholar]

- Sanders Phillips K. Assaultive violence in the community: Psychological responses of adolescents and their parents. Journal of Adolescent Medicine. 1997;21:356–365. doi: 10.1016/S1054-139X(97)00165-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schier LM, Botvin GJ, Miller NL. Life events, neighborhood stress, psychological functioning, and alcohol use among urban minority youth. Journal of Child and Adolescent Substance Abuse. 1999;9:19–50. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzer R, Mueller J, Greenglass E. Assessment of perceived general self-efficacy on the Internet: Data collection in cyberspace. Anxiety, Stress, and Coping. 1999;12(2):145–161. [Google Scholar]

- Shrout PE, Bolger N. Mediation in Experimental and Nonexperimental Studies: New Procedures and Recommendations. Psychological Methods. 2002;7(4):422–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoemmes F. Reversing arrows in mediation models does not distinguish plausible models. Basic and Applied Social Psychology. 2015;37(4):226–234. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Bureau of the Census. The Black Population in the United States. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Voisin DR, Hotton AL, Neilands TB. Testing pathways linking exposure to community violence and sexual behaviors among African American youth. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2014;43:1513–1526. doi: 10.1007/s10964-013-0068-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waller E, DuBois D. Investigation of stressful experiences, self-evaluation, and self-standards as predictors of sexual activity during early adolescence. Journal of Early Adolescence. 2004;24(4):431–459. [Google Scholar]

- White R. Reconceptualizing HIV infection among poor Black adolescent females: An urban poverty paradigm. Health Promotion Practice. 2002;3(2):302–312. [Google Scholar]

- Young AA., Jr . The minds of marginalized Black men: Making sense of mobility, opportunity, and future life chances. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]