Abstract

Objectives

Knowledge of the structural organization and mechanical properties of dentin has expanded considerably during the past two decades, especially on a nanometer scale. In this paper, we review the recent literature on the nanostructural and nanomechanical properties of dentin, with special emphasis in its hierarchical organization.

Methods

We give particular attention to the recent literature concerning the structural and mechanical influence of collagen intrafibrillar and extrafibrillar mineral in healthy and remineralized tissues. The multilevel hierarchical structure of collagen, and the participation of non-collagenous proteins and proteoglycans in healthy and diseased dentin are also discussed. Furthermore, we provide a forward-looking perspective of emerging topics in biomaterials sciences, such as bioinspired materials design and fabrication, 3D bioprinting and microfabrication, and briefly discuss recent developments on the emerging field of organs-on-a-chip.

Results

The existing literature suggests that both the inorganic and organic nanostructural components of the dentin matrix play a critical role in various mechanisms that influence tissue properties.

Significance

An in-depth understanding of such nanostructural and nanomechanical mechanisms can have a direct impact in our ability to evaluate and predict the efficacy of dental materials. This knowledge will pave the way for the development of improved dental materials and treatment strategies.

Conclusions

Development of future dental materials should take into consideration the intricate hierarchical organization of dentin, and pay particular attention to their complex interaction with the dentin matrix on a nanometer scale.

Keywords: Dentin, Collagen, Proteoglycans, Intrafibrillar Mineral, Remineralization, Organs-on-a-chip

1. Introduction

The field of restorative dentistry has evolved considerably in the past two decades. New restorative methods have been proposed, the concept of regenerative dentistry has been brought forward, and existing dental materials have increasingly become more biocompatible 1, bioactive 2 and biomimetic 3, 4. Key to such developments has been a profoundly more in-depth understanding of the tissues that compose the tooth at smaller length-scales.5 This has been made possible by the fast development of characterization tools and techniques that can probe tissue structures at ever-finer scales.

Dentin is the largest structure in the tooth, and is composed of hydroxyapatite mineral crystallites, collagen fibrils (mostly type I) and noncollagenous macromolecules 6. A great number of current restorative procedures use dentin as a substrate, therefore, the success of restorative dental materials invariably depends on a thorough understanding of the structural and mechanical property relationships that characterize the dentin matrix. Moreover, dentin, together with dental enamel, represents a unique biomaterial in nature, in that it retains outstanding durability despite the life-long cyclic loading imposed onto the tooth, and the absence of cell-regulated mechanisms of remodeling or repair 7 that are common in other tissues. Therefore, dentin offers a classic example of how nature designs stiff and tough natural biomaterials with outstanding longevity, simply by combining soft (proteins) and rigid (mineral) building blocks at precisely organized hierarchical levels. 3 Thus, if from a reverse engineering standpoint the ultimate goal of restorative dental materials is to closely approximate the longevity and properties of the tooth, knowledge of the mechanisms endowing dentin with its outstanding properties is imperative.

In this review we cover recent findings regarding the mechanical and structural relationships of dentin on the nanoscale. We adopt a hierarchical approach to explore aspects that relate to both tissue nano-structure and nano-mechanics, and the relative participation of the inorganic and organic constituents that make up the tissue matrix. Regarding the former, we discus the specific participation of the intrafibrillar mineral to the mechanical properties of dentin. On the latter, we cover the specific structural and mechanical contributions of collagen and, more in depth, non-collagenous nanoscale components, as determined by various analytical methods. Additionally, we offer specific insights into the challenges and limitations of existing dental materials and treatments (i.e. remineralization and bonding), especially in relation to the complexity of dentin proteins on the nanometer and molecular length scales. Finally, we provide a forward-looking overview of the gradual transition of dentistry into the emerging fields of bioinspired materials engineering and regeneration. We discuss how these emerging topics will influence the development of novel dental materials with properties that more closely approximate those of the natural structures in the tooth, and hence will provide impetus for the shift of clinical dentistry from reparative-based treatment methods to more biologically-assisted regenerative approaches.

2. Dentin inorganic content – extrafibrillar and intrafibrillar mineral

During development, differentiated odontoblasts secrete the dentin matrix in a well orchestrated sequence that is characterized by the release of collagen fibrils with high concentrations of carboxylated non-collagenous proteins 8, 9 and proteoglycans 10. These matrix constituents, respectively, regulate the process of mineral deposition 11, 12 and fibrillogenesis 13 during dentin formation. The process of collagen biomineralization has been a topic of much debate in the recent literature. Although it has long been acknowledged that collagen mineralization occurs due to mineral release from vesicles in the extracellular matrix (which have also been called calcospherites early on), it has recently been demonstrated that prior to secretion, the mineral accumulates intracellularly in the mitochondria 14, and travels to the extracellular space where it accumulates calcium while it remains in the form of amourphous calcium phosphate until full release onto the collagenous network 15–18.

Extensive work has shown that acidic non-collagenous proteins of the SIBLING family 11 assist in stabilizing the calcium phosphate in the amorphous phase, aiding the penetration of the amorphous mineral in the gap zones and intermolecular spaces of collagen fibrils via capillary forces and osmotic-regulated mechanisms 19, 20. Subsequent phase transformations allow the amorphous mineral to adopt a more crystalline and stable hydroxyapatite morphology 21, and form what is known as the intrafibrillar mineral. Interestingly, contrary to the long help perception that intrafibrillar mineral requires either non-collagenous proteins or synthetic polymeric protein-analogues to form, Wang et al demonstrated that intrafibrillar mineral can form in the absence of these acidic directing-agents, as long as the collagenous matrix has a high density that approximates that of natural bone or dentin 22. As a consequence of this well orchestrated process of biominerlization, a carbonated calcium-deficient hydroxyapatite mineral phase becomes the primary constituent of dentin. Approximately 50% by volume, 65% by weight (wet) of the tissue is composed of plate-like irregular hydroxyapatite (HAP) nanocrystallites (~100 × 30 × 4 nm). 23 These are situated either within collagen fibrils (intrafibrillar) or between the fibrils, and (called either extra- or inter-fibrillar mineral) 24.

As mentioned above, it is generally accepted that nucleation of HAP nanocrystals begins in the gap zones of collagen fibrils 25 and progresses via crystal growth and lengthening longitudinally between the intermolecular spaces separating collagen triple-helical molecules in a fibril (for a comprehensive description of the collagen hierarchical organization in dentin see 6). This is relevant because it means that the specific size, thickness and alignment of the intrafibrillar mineral, are all guided (or physically restricted) by the adjacent collagen molecules, whereas the extrafibrillar mineral does not have such constraints; and thus the extrafibrillar mineral can assume more random orientations and have larger sizes. 26 For instance, mineral in the collagen-free peritubular dentin has been shown to have a thickness of more than 10 nm 27. Conversely, Kinney et al performed small angle x-ray scattering (SAXS) measurements on slices of dentine to conclude that the crystals in deep primary dentin are needle-like (unlike the more plate-like crystals found elsewhere), and have a thickness of ~5 nm. Tesch et al 28, on the other hand, used a more systematic analysis to show that the mean thickness of mineral platelets decreases from 3.6 nm to 2.3 nm in areas closer towards the pulp. These values are closer to the values presented more recently by Marten et al, who used small angle X-ray scattering to map 2D and 3D variations in mineral particle characteristics in entire molar crowns, and found a mean mineral platelet thickness of 3.2 nm decreasing to 2.6 nm farther beneath the dentin-enamel junction (DEJ), and becoming even thinner in deep dentine surrounding the pulp.

It is interesting to note that a major discrepancy in this field has been the lack of correlation in the intermolecular spaces within collagen fibrils – which is usually obtained from studies on non-mineralized collagen type I – and the size of mineral crystallites. For instance, it has long been acknowledged that the spaces separating the triple-helical molecules that compose a collagen fibril are in the range of approximately 2 nm. Nevertheless HAP crystals as large as 5 nm have been reported in the literature. To address some of the questions resulting for such discrepancies, Bonar et al used neutron diffraction measurements of intact and demineralized hydrated bone, and determined the packing density of collagen molecules in mineralized bone collagen fibrils (which is representative of the space available for the mineral occupy) to be 1.24 nm, and this spacing increased considerably to 1.53 nm upon demineralization.29 The specific size of the mineral that is formed inside of the fibrils is of particular relevance for restorative treatments, especially adhesion to dentin, since dentin has a similar nanostructure to bone, and dental bonding depends on the putative penetration of adhesive monomers into collagen fibrils that have been demineralized 30. Hence the space available for monomer penetration is arguably dependent upon the thickness of the mineral crystallites that once occupied the intrafibrillar compartment. We discuss this aspect further in section 3.1 below.

2.1 The importance of the intrafibrillar mineral

The presence and relevance of the intrafibrillar mineral in calcified tissues has been studied for many years. Early discussions surrounded the location and partitioning of the intrafibrillar mineral relative to the extrafibrillar component in these tissues 31. In the early 2000’s, work by Kinney at al was instrumental in providing insights into the specific contribution of the intrafibrillar mineral to the mechanical properties of dentin.32, 33 Initially, high-resolution synchrotron radiation computed tomography (SRCT) and SAXS were used to show that dentin in teeth affected by dentinogenesis imperfecta type II (DI-II) had approximately 33% less mineral than healthy dentin. Most importantly, the DI-II dentin showed virtually no low-angle diffraction peaks corresponding to the presence of intrafibrillar mineral, consistent with the absence of intrafibrillar mineral. 32

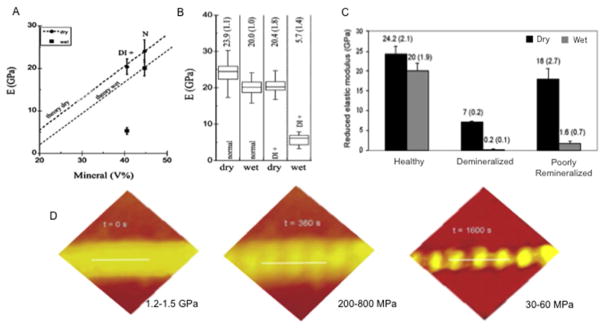

In a subsequent report, DI-II dentin was used to study the mechanical contribution of the intrafibrillar mineral by comparing the nanoindentation elastic modulus of healthy dentin versus that of DI-II-affected dentin. 32 Healthy dentin had a mean mineral volume of about 44.4%, whereas mineral volume in DI-II dentin varied from 30.9 – 40.5%. More surprisingly, the elastic modulus of dentin when measured in a hydrated state dropped drastically from 20±1 GPa in healthy dentin down to only 5.7±1.4 GPa in the DI-II dentin, despite only a moderate decrease in total mineral volume (Figure 1). These results have been interpreted on the basis of a simple rule of mixtures and the added shear stresses between mineral nanocrystals in intrafibrillar compartment 34–37, which is virtually lost in dentin lacking intrafibrillar mineral.

Figure 1.

The mechanical contribution of interfibrillar mineral to dentin collagen. A) Healthy dentin had a mean mineral volume of 44.4%, whereas the mineral volume in DI-II dentin varied from 30.9 – 40.5%. B) The mean elastic modulus of healthy dentin measured in dry was of 23.9 GPa, and dropped to 20±1 GPa when wet. DI-II dentin, which lacks intrafibrillar mineral, was 20.4 GPa wet, and dropped drastically to only 5.7 when wet, despite only a moderate decrease in total mineral volume. C) A similar trend is found in some cases of poorly remineralized dentin, where the average elastic modulus in dry can be has high as 18 GPa, and as low as 1.6 in wet. D) A continuous deminerlization of single dentin collagen fibrils reveals the topographical changes in collagen with the loss of intrafibrillar mineral (especially in the gap zones), with a drastic decrease in AFM-indentation elastic modulus.

These early reports formed the basis for a series of contributions relative to the effective analyses of remineralized carious dentin. The conjecture that dentin lacking intrafibrillar mineral and having only a moderate decrease in mineral volume ratio caused a drastic decrease in mechanical properties begged the question whether simply determining mineral uptake by the tooth was a sufficient end point to determine successful remineralization. In 2009 a review paper published by our group summarized these questions, 38 which together with other works describing the complexity of intrafibrillar remineralization in dentin 39 provided impetus for a significant shift in the existing remineralization strategies and the evaluation of remineralized dentin. Accordingly, we showed that the nanoindentation modulus of dentin that was poorly remineralized could be as high 18 ± 2.7 GPa when measured in dry; however, when the same specimen was measured in wet conditions the elastic modulus dropped to only 1.6 ± 0.7 GPa, which is a drastic decrease of over 90% on average modulus (Figure 1). Two important interpretations resulted from these analyses: firstly it became apparent that mechanical properties of remineralized dentin measured in dry conditions might lead to false positive results; secondly, since hydrated dentin that lacked intrafibrillar mineral (DI-II dentin) had sharply lower modulus than healthy dentin - despite comparable mineral density (DI-II 40.5% vs. Healthy 44%) - it became apparent that effective dentin remineralization (determined on the basis of mechanical recovery) was only possible if both the extrafibrillar and intrafibrillar mineral components were replenished, (Figure 1) a conjecture that is largely supported today. Consequently, several strategies to remineralize dentin proposed to date highlight the importance of recovering the intrafibrillar mineral of demineralized (and carious) dentin (see 40, 41 for recent reviews), a process that has also been called functional remineralization, biomimetic remineralization, hierarchical remineralization and other similar terms. Similarly, these studies contributed to the development of numerous novel strategies that seek to prevent degradation of dentin-adhesive interfaces 41, of scaffold materials with improved biological and physical properties 42, and even the treatment of disease conditions such as DI-II-like dentin (Dspp knockout mice) 43. More importantly, these reports contributed to a significantly deeper understanding of the nanoscale and nanomechanical events that are now known to regulate the remineralization of dentin.

3. Dentin organic matrix

3.1 Collagen

The hierarchical organization of collagen fibrils in dentin has been a topic of a recent a review by our group where we describe the structure and properties of collagen from the molecular to the micrometer length scale.6 Thus, here we will focus primarily in describing recent advances in the field in the past few years, as opposed to revisiting the structure of collagen in-depth.

Collagen represents one of the most intricate biological entities in the animal kingdom, where type I fibrillar collagen is also the most abundant protein in all species.44 Therefore, it is needless to say that research concerning the structure and properties of collagen surpasses the boundaries of dental research and dates back to several decades ago.45 Unfortunately, the complex interactions of dental materials with the molecular and nanostructure of dentin collagen, especially regarding the internal structure of individual fibrils, which is of tremendous relevance for dentistry, has only began to be explored in greater detail in recent years. For instance, many text books used to teach restorative and operative dentistry to date still characterize dentin collagen up to the fibrillar structural level, 46 despite the fact that the foundation of modern restorative/adhesive dentistry based on the seminal work of Nakabayashi et al 30, 47–49 relies on the proposed ‘enveloping and penetration’ of individual collagen fibrils with adhesive monomers. This invariably means that a good understanding of the internal structure of collagen is imperative to understand how monomers may interact with dentin at a fine scale. The requirement for such in-depth understanding has become even more relevant once the challenges of dentin nanoleakage have become increasingly evident in the literature.50–52

Research has shown that dentin collagen has a typical diameter of approximately 80–100 nm,53 although other tissues have shown a much wider range of diameters. 54–57 From larger to smaller structural features, collagen fibrils in dentin are essentially comprised of an array of laterally organized microfibrillar units, commonly referred to as collagen microfibrils. 58–60 Recent work from our group suggests that these microfibrils may self organize in a ‘twisted’ array of bundles measuring approximately 20 nm each, 61 therefore representing the second hierarchical level in dentin collagen within each of the 80–100 nm fibrils. However, these structures remain poorly characterized and their existence thus far has not been fully confirmed. Accordingly, these structures may also represent a transient state of collagen molecules that are more resistant to enzymatic degradation than others, as it has been reported for collagen in cartilage and tendon 62. Regardless, the next level of organization in dentin collagen is in the order of 5–6 nm in diameter, and relates to each individual collagen microfibril. Laterally, individual microfibrils are composed of 5 stranded tripled-helical collagen molecules that are organized in a quasi-hexagonal supramolecular supertwist 60. In other words, this means that each of the 5 triple-helical collagen molecules composing one microfibril is twisted around its own longitudinal axis and wrapped with 4 adjacent molecules in an arrangement that forms a near hexagonal shape. The molecules are staggered in a way that the repeating pattern of hundreds of them creates what is typically known as the D-periodical banding of collagen type I. Each triple-helical molecule has two alpha 1 and one alpha 2 chains intertwined via hydrogen bonds and electrostatic interactions along approximately 300 nm. Importantly, these individual chains are composed of a “coding system” (or recognition motifs) which are formed by the presence of specific amino acid sequences (X, Y, Gly), which ensure that each area of individual alpha chains can bind to adjacent chains, as long as the conditions for such recognition is adequate (i.e. collagen fibrillogenesis can occur at neutral pH despite the absence of cells or proteoglycans which are known to assist in the process of fibril formation). 63

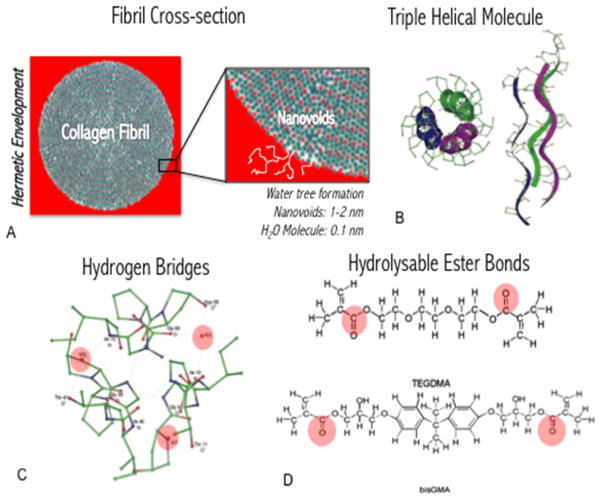

At the fibrillar level, several structures give rise to what may be described as collagen fibril surface nanostructural roughness. Gap and overlap zones form peaks and valleys at every 67 nm of each individual fibril. This repeated pattern (also known as collagen D-period) can interlock in a way that every valley (gap zone) is tightly adapted onto a peak (overlap zone) of an adjacent fibril, 53 even when the collagen is hydrated. Each individual microfibril (5–6 nm) that composes a larger fibril (80–10 nm) can be visualized as longitudinal streaks on the surface of collagen fibrils via electron or atomic force microscopy 64–67; and it is important to note that these structures are tightly bound with water molecules due to the inherent hydrophilic nature of collagen moieties. These nanometer scale ‘streaks’ may contribute to the formation of what has been called “nanovoids” 6 during the steps of enveloping collagen with monomer molecules.68 It is important to note, also, that both dentin (at the tissue level) and collagen (at the molecular level) are inherently hydrated, and many monomers used in dentistry can undergo hydrolysis if kept in water for too long. Hence, such nanovoids can lead to the process of water tree formation 69 that is typically seen in nanoleakege studies. Moreover, the pulpal pressure may facilitate diffusion of water molecules through these nanometer scale voids (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of potential mechanisms of monomer hydrolysis within the hybrid layer. A) Collagen fibrils (in cross section) require hermetic enveloping with adhesive monomer, however nanoscale voids may allow for diffusion of water from the pulp, which leads to the formation of the so-called water trees. B) Triple-helical collagen molecules, which make up the collagen fibril, contain inherent hydrogen bridges (in C highlighted in red for a single cross-sectional region in a molecule) which allow for diffusion and ‘storage’ of water molecules within the protein. D) The interaction of the water molecules, which is an inherent property of collagen in physiologic conditions, leads to degradation of hydrolysable and degradable ester bonds in common dental monomers (TEGDMA and bisGMA shown – ester bonds highlighted in red).

At the microfibrillar and molecular levels, several studies have attempted to dissect the specific separation distance between individual triple helical molecules composing individual microfibrils (which form a fibril) (See 70 for a review). Interestingly, studies of the intermolecular space separating individual molecules in a fibril date back to the 70s and earlier,45 and it has been well reported since then that not only these spaces are occupied by water molecules, but also that they are in the order of a few angstroms.71–73 The most recent model describing the molecular organization of collagen type I shows that the space between triple helical molecules averages at about 1.3 nm.60 That is to say that the space available for individual molecules to infiltrate is less than 2 nm.

In a recent review paper published by our group, we challenged the conjecture that such penetration was possible. That was based on the fact that (1) monomer molecules, for the most part, are delivered to dentin using high-density and relatively high-viscosity monomer blends (or low viscosity primers) that rely on diffusion alone to penetrate the collagen structure; and (2) we argued that the size of individual monomers might be too large to fit between the 1.3 nm intermolecular space within collagen fibrils. However, we failed to consider the wide range of motion that individual molecules can adopt in a given solvent, which may allow them to ‘squeeze’ into very tight spaces, such as within collagen fibrils. Work done by Takahashi et al following our publication was instrumental in experimentally challenging the concept that we presented, and researchers were able to demonstrate that molecules typically used in common adhesive systems (i.e. HEMA and TEGDMA) could in fact penetrate the internal structure of dentin collagen, which is a very significant finding. Having said that, these experiments where performed with solubilized monomer molecules, as opposed to resin blends as used in adhesive systems, and in near ideal experimental conditions that are typically not found in the oral cavity. Additionally, it has been well documented that collagen molecules are individually wrapped by water forming cylinders of hydration (Figure 2), and although monomer molecules may infiltrate the internal structure of collagen it remains to be de determined whether or not the water in collagen is totally replaced by monomer molecules, which is quite unlikely. This internal hydration may be the reason for the hydrolytic degradation of the ester-containing monomers in the hybrid layer and the formation of the so-called water trees (Figure 2).

In summary, from a clinical stand point and taking into account the past decade in the literature, it is very well documented that nanoleakage is very common occurrence. Considering that (1) water molecules may degraded common dental monomers, (2) dentin and collagen are inherently hydrophilic and hydrated, (3) the pulpal pressure will invariability push water into the dentin-biomaterial interface, (4) the surface area of fibrils available for enveloping and infiltration is likely superior to the number of available monomer molecules to hermetically impregnate and wrap them, it comes to little surprise that the biomaterial/tooth interface remains the weakest link in restored teeth and that nanoleakege will continue to occur. Therefore, research should focus on not only overcoming these limitations, but also properly characterizing the interactions that weaken the dentin-biomaterial interface at the molecular and nanostructural length scales.

3.2 Non-collagenous components

Although dentin is primarily composed mineral, collagen and water, it has been well documented that non-collagenous proteins, proteoglycans and several enzymes play a fundamental role in the homeostasis of the tissue. Each one of the individual non-collagenous entities in dentin has been a topic of focused reviews in recent years. The author is encouraged to refer to those papers, which have dealt with several aspects relative to the participation of MMPs in collagen/bonding degradation 74–76, of anionic carboxylated proteins in mineralization and development 11, and of proteoglycans in dentinogenesis 10. Here we will concentrate on the specific participation of key non-collagenous components in the biomechanics and structure of dentin and mineralized tissues of similar composition.

3.2.1 Proteins of the SIBLING family

The small integrin-binding ligand N-linked glycoprotein (SIBLING) family consists of osteopontin (OPN), bone sialoprotein (BSP), dentin matrix protein 1 (DMP1), dentin sialophosphoprotein (DSPP) and matrix extracellular phosphoglycoprotein (MEPE). 8, 11 For a number of years these macromolecules have been characterized by their important participation in biomineralization during tissue development. Since these non-collagenous proteins constitute less than 5% of the dentin and bone matrices by volume, their participation in the structure and mechanical function at a tissue level have long been underestimated.

An important set of papers by Hansma’s group in the early 2000s 77–81 used atomic force microscopy (AFM) force-spectroscopy 82, 83 to separate bone collagen fibrils and individual bone fragments to show that mineralized fibrils are interconnected with non-collagenous proteins that can be stretched, unfolded and refolded during tissue fracture.77 This mechanism was attributed to the presence of non-collagenous proteins of the SIBLING family in the interfibrillar region - although the involvement of proteoglycans was not ruled out. Thompson 77 and Fantner et al 81 demonstrated that as collagen fibrils separate during tissue fracture, the ability of non-collagenous proteins to unfold before they fully rupture required the disruption of intramolecular bonds that hold the protein in a folded state, and as such bonds are broken, they dissipate significant levels of mechanical energy. More importantly, this mechanism can be repeated several times, every time that the collagenous network is subjected to stress at the nanometer scale, which is believed to increase tissue durability dramatically. These mechanisms gave rise to a concept where non-collagenous proteins began to be called the glue within our bones.

Importantly, work by Adams et al 84, demonstrated that one of the non-collagenous proteins that has the ability of unfold to dissipate mechanical energy on the nanoscale is DMP1, which is found abundantly in dentin, and also in bone. Therefore, it is highly likely that similar mechanisms of mechanical energy dissipation are also present in dentin, and similar properties have also been described for inter-prismatic enamel proteins 85–87.

3.2.2 Proteoglycans

Similar to the SIBLING proteins described above, proteoglycans (PGs), which differ from other non-collagenous proteins in that they are (generally) constituted of a protein core covalently attached to a carbohydrate glycosaminoglycan (GAG) side chain,88 represent less than 3% of the dentin matrix by volume; and since their volume fraction is far less than those of collagen and apatite in mineralized tissues, their mechanical and structural participation has also been poorly explored for a number of years. This is an interesting conjecture, since PGs are known that play a fundamental role in the structural organization of the extracellular matrix (ECM) of soft tissues in all vertebrates.

PGs are believed to form interfibrillar supramolecular bridges between collagen in both mineralized and soft tissues 89–91. The GAG component of PGs is highly negatively charged, which allows GAGs to interact with one another between contiguous fibrils in an anti-parallel fashion (head-to-tail), forming tape-like aggregates that are further stabilized by electrostatic forces, H-bonds and hydrophobic interactions 90, 91. Due to such a multi-level relationship, PGs and GAGs are known to absorb water and span the spaces between fibrils, which effectively signifies that the collagenous network is interconnected and held together by these non-collagenous structures on the nanoscale. Decorin (Dcn) and Biglycan (Bgn) are the two most abundant PGs in dentin whereas chondroitin-4-sulfate (C4S) and chondroitin-6-sulfate (C6S) appear as the most relevant GAGs in the matrix. 89, 92 Nevertheless, studies have also identified lumican, versican 93 and trace amounts of fibromodulin in murine dentin 94, 95.

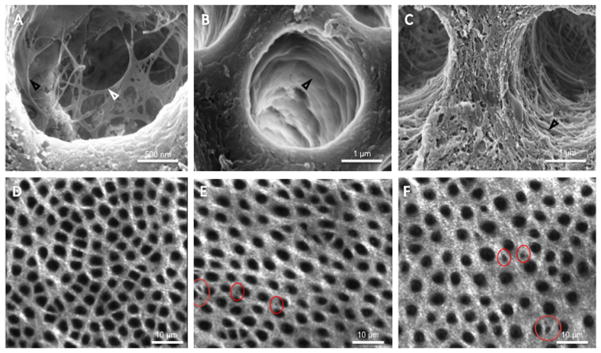

The specific distribution of PGs and GAGs in dentin has recently been a topic of debate in the literature. A series of publications from Breschi’s group used gold labeling electron immunohistochemistry to show an increased presence of PGs and GAGs near the dentine tubule walls. 96–100 This conjecture was further supported by recent studies in our lab where PGs appeared to form a membrane (lamina limitans) separating the intertubular from the peritubular dentin, while GAGs protruded out into the tubules forming an organic network that was not resistant to degradation with chondroitinase-ABC (C-ABC) (Figure 3A–C). 101 Other recent studies determined the distribution of PGs and GAGs in carious dentin and demonstrated that tertiary dentin lacks these interfibrillar structures. 102 However, their specific distribution of on a micro- to nanoscale remains unresolved. Recent preliminary work in our lab using second-generation harmonics microscopy, where the microscale structure and organization of the organic dentin matrix is visible without the requirement for demineralization, showed that microscale intertubular gaps or “holes” appear upon degradation of either GAGs, using C-ABC, or of the whole pool of non-collagenous proteins and PGs, using a trypsin enzyme (Figure 3D–F). This is in agreement with earlier data by Hablitz et al 53 where similar microscale intertubular gaps were imaged by AFM on the surface of fully demineralized dentin treated with a non-specific bleach solution. These observations point to the question of whether PGs and GAGs accumulate in higher concentrations in specific areas of the intertubular region of mineralized and mature dentin, as though they formed islands of concentrated PGs within the tissue, which remains to be tested more in depth.

Figure 3.

Proteoglycans (PGs) and glycosaminoglycans (GAGs) in peritubular and intertubular dentin. A) Mild acid etching reveals organic network within peritubular space. B) Enzymatic removal of GAGs reveals the dentin lamina limitans, an organic membrane separating the inter- and peritubular dentin. C) Removal of non-collagenous proteins and PGs with trypsin completely removes the lamina limitans and organic network, suggesting that the peritubular dentin is primarily composed of GAGs (network) and PG protein core (lamina limitans). In second generation harmonic microscopy healthy intertubular dentin appears homogenous, whereas removal of GAGs (E) and PGs (F) reveals voids (red circles) within the intertubular dentin matrix.

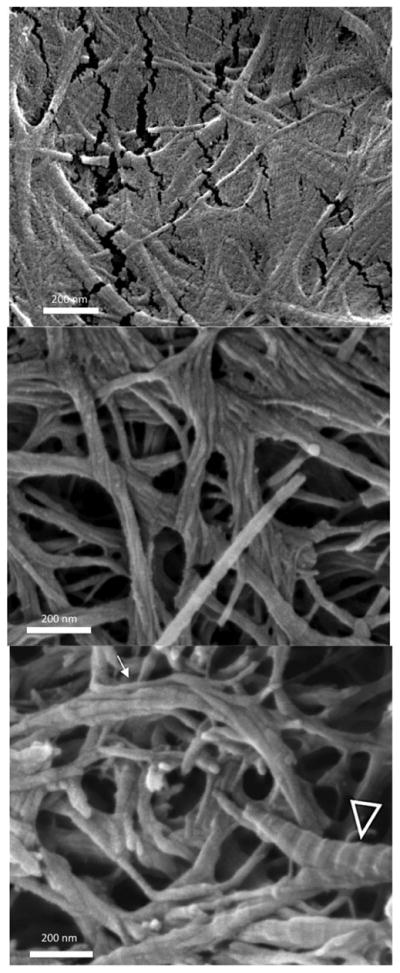

More interestingly, recent studies on the contribution of proteoglycans and other noncollagenous proteins suggest that these macromolecules may assist in the post-translational organization and stability of collagen fibrils in dentin. Knockout mice with targeted disruption of decorin leads to abnormal collagen morphology in skin. Recent work by Antipova and Orgel using polyclonal antibodies against the proteoglycan biglycan showed extensive collagen type II destruction. 103 Motivated by these observations, our group studied the nanoscale fibrillar disintegration of dentin collagen type I upon enzymatic degradation of PGs and other non-collagenous macromolecules with trypsin 104 (and earlier with papain 105 enzymes). Demineralized dentin showed the typical banded morphology of D-periodical collagen type I, however, upon enzymatic digestion with trypsin, normal collagen fibrils appeared to dissociate longitudinally, consistently unraveling ~20 nm structures which we referred to as microfibril bundles.104 (Figure 4A–B) These structures, which may be transient in the nature of their disaggregation, appear to form a new and poorly explored level of intrafibrillar organization that deserves further attention.

Figure 4.

Microfibril bundles in dentin collagen. Demineralized fibrils: A) The D-banding pattern of collagen fibrils in demineralized dentin is preserved. Trypsin treated: B) The D-periodic pattern of the fibrils is still visible in some fibrils (arrowheads), while the untwisting phenomenon is seen (white arrow) resulting in thinner (~20 nm) microfibril bundles, which are more clearly seen in (C).

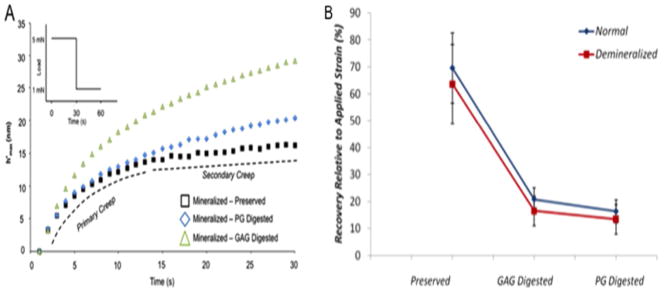

From a mechanical standpoint, it is natural to hypothesize that, if PGs and GAGs interconnect the organic network of mineralized tissues guaranteeing the stability of the extracellular matrix, loss of these interfibrillar molecules should be associated with a significant deterioration of mechanical properties. Our group and others have tested this hypothesis extensively in recent years, and there is growing evidence that PGs and GAGs indeed regulate important mechanisms of mechanical deformation in dentin and bone. 92

Recent nanoindentation studies tested the strain recovery ability of dentin lacking PGs and GAGs against that of normal/untreated dentin. Results demonstrated that the creep strain recovery ability of dentin decreases drastically by nearly 75% when either PGs or GAGs are removed (Figure 5).106 Nanoindentation properties of PG- and GAG-digested cementum and dentin also suggested that the removal of GAGs decreases the hardness and elastic modulus of both tissues significantly. 107 And a similar deterioration in mechanical properties leading to osteoporosis-like phenotype is observed in biglycan-deficient bone extracted from biglycan knock-out mice. 108

Figure 5.

Mechanical contribution of PGs and GAGs. A) Creep response of mineralized dentin before and after digestion of PGs and GAGs. B) Relative creep recovery of mineralized dentin before and after digestion of PGs and GAGs.

A number of theories have been proposed and reviewed to explain the mechanical participation of PGs and GAGs in mineralized tissues, and in summary these interfibrillar macromolecules are believed to function both on the micro- and nanoscale. Microscopically, it has been suggested that the electrostatic interactions occurring within the negatively charged GAGs may lead to an expansion of the PG molecule in solution, which contributes to an increased hydrostatic pressure in the collagen–PG network, thus leading to increased stiffness of the tissue 107,109. Moreover, the presence and function of PGs and GAGs in the intertubular dentin as microscale regulators of absorption of water has been linked to the possible regulation of fluid flow within the porous collagenous network when the tissue is under mechanical stress, which has also been described as the poroelastic behavior of dentin. 92 On a nanoscale, anti-parallel GAGs have been proposed to slide against one another reversibly breaking and reforming ionic interactions with the positive ions in the medium, which has been called the sliding filament theory. 110 Additionally, intramolecular stretching of individual GAG moieties has been demonstrated with the use of AFM-based force-spectroscopy studies. 111 In summary, there is sufficient evidence that dentin lacking PGs and GAGs suffer from a decrease in strength and ductility, nanoindentation hardness and elastic modulus and especially time dependent strain recovery ability.

5. Bioinspired Fabrication – Looking Ahead

5.1 Bioinspiration for Dental Materials Design

After reviewing the hierarchical organization of dentin from a molecular to a microscale, and taking into account both structural and mechanical aspects, it becomes evident that dentin combines multiscale mechanisms to endow teeth with advanced properties and durability. Recent work has drawn inspiration from these natural tissues to attempt to reverse engineer these mechanisms in artificial materials. This is an emerging trend in biomaterials design that has been typically referred to as bioinspired engineering or biomimetics, and several examples of bioinspired materials design are available in the recent literature (see 3 for a recent review).

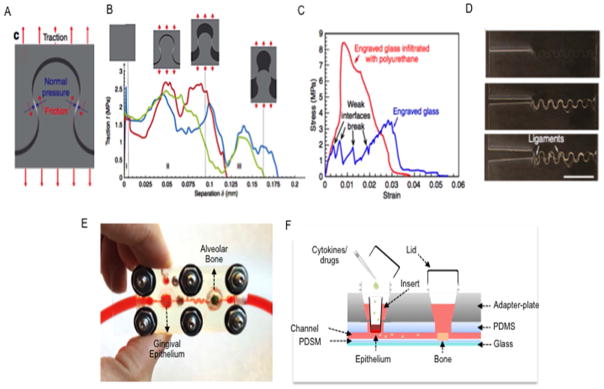

For instance, interesting recent developments have attempted to mimic toughening mechanisms observed in dentin, enamel and bone, where soft proteins or tubules guide crack propagation in a direction of least resistance against crack growth to, counter intuitively, result in greater toughness. In dentin, these mechanisms have been originally described in a series of papers by Arola’s group, where it was demonstrated that the fluid filled and hollow dentin tubules have the ability to guide crack propagation from one tubule to another, while the stiff peritibular dentin has the ability to induce crack deflection, blunting or bridging, thus diminishing the concentration of stresses in a single crack tip, and splitting one large (and perhaps catastrophic) crack into several smaller (and less critical) cracks.112–116 Enamel uses a similar mechanism, where inter-prismatic proteins that have negligible stiffness permit cracks to propagate between near-parallel prisms in the outer enamel, only to guide them into a decussation region, where parallel prisms become twisted and crossed, which prevents further propagation of interprismatic cracks deeper into dentin. 117, 118 Drawing inspiration from these natural smart materials, Mirkhalaf et al created pre-designed micro-cracks in ceramic-like glass materials with a self-interlocking architecture (Figure 6A–D). These cracks were impregnated with a soft resin, inspired by the inter-prismatic protein layer in enamel, or non-collagenous proteins in dentin and bone, and results showed that the self-interlocking resin-impregnated system increased the toughness of the specimens up to 200 times.119 A similar increase in resistance against crack propagation was observed by Dimas et al, who used a 3D printer to replicate the staggered brick structure that is observed in mineralized collagen using resins of high and low stiffness, although in much larger dimensions. 120–122

Figure 6.

Emerging examples of bioinspired engineering and biomimetic materials design: (A–D) Bioinspired materials design. (E–F) Organs-on-a-chip. A) A jigsaw-like interface is engraved in front of the main crack in a glass sample. B) When the crack propagates along the engraved interface the jigsaw tab is pulled out, and normal pressures and frictional tractions develop. C) Further impregnation of polyurethane within the cracks replicates the function of folding-unfolding sacrificial proteins in biological materials, such as enamel, nacre and bone. Combined these bioinspired toughening mechanisms can make standard glass 200 times tougher. E) Prototype to mimic periodontal inflammation on-a-chip. F) The gingival epithelium chambers house engineered cell-laden oral epithelium tissue constructs on a transwell plate insert. Addition of chemicals or inflammatory mediators stimulates exacerbation of inflammation of the epithelium which triggers cells to secrete cytokines that are microfluidically carried to the alveolar bone tissue construct downstream, where inflammation mediated osteoclastic activity is activated and measured in real time via soluble factors.

Certainly, dentin and craniofacial tissues can provide examples of how to fabricate strong and durable artificial materials by integrating soft and hard structural components, and this represents and interesting strategy that the dental materials community should capitalize on.

5.2 Bioinspiration for Regenerative Dentistry

The concept of developing regenerative scaffold materials that mimic the structure and properties of native tissues is not new. This concept dates back to decades ago, when the field of tissue engineering was first implemented.123 However, more recent approaches have taken advantage of both microtechnologies and 3D printing to allow for even more biomimetic scaffold design and fabrication. Hydrogel lithography, for instance, is one of such methods. Hydrogel microfabrication via soft lithography uses a range of techniques that were originally developed for the semiconductor and microelectronic industries (MEMS - microelectro mechanical systems), and were later adapted for use with cell-friendly polymers to allow for the fabrication of scaffold systems with controlled features at length scales from 1 μm to 1 cm. 124 The field of hydrogel microfabrication has matured significantly and has allowed for the engineering of truly disruptive scaffolds systems, such as autonomously and synchronously beating hearts,125 functional and pre-patterned blood vessels 126 and several other examples that fall beyond the scope of this review. We encourage the reader to refer to a recent review paper by our group that has covered this subjected at length.127

Interestingly, the technology to engineer scaffolds precisely mimicking the structure of dentin tubules in cell-friendly hydrogels is already within reach. 128 However, studies directed at using hydrogel microfabrication for dental tissue engineering have remained scarce in the literature. More importantly, not only have these methods permitted structurally biomimetic scaffolds to be developed, but also they have allowed mechanistic questions to be probed at much finer and more precise scales. For instance, studies on the importance of the alignment of various cells for their expected function to be maintained have been reported. 129 Similarly, experiments where the levels of paracrine factors secreted by different cells types relative to gradient concentrations within the scaffolds have also been published. 130 And this ultimately represents a direction that can benefit the dental research community in its attempts to regenerate functional tooth structures. Moreover, significant efforts have been made recently to scale up the precision obtained with microscale technologies and microfabrication in the third dimension with the use of 3D bioprinting. And in fact several tissue prototypes relevant to the craniofacial region have already been 3D bioprinted,131 including blood vessels,132–134, ECM-derived hydrogels 135, 136 bone, 137 and several others. A recent review devoted to describing recent advances in 3D bioprinting in craniofacial regeneration was published recently and is a source of further information. 138

5.2.1 Organs-on-a-chip

Finally, attempts to mimic the function of tissues and organs have reached another level of complexity with recent developments in the emerging field of organs-on-a-chip. 139, 140 The concept of organs-on-a-chip integrates technologies from microfabrication, microfluidics, tissue engineering and biosensing to generate improved in-vitro models of organ function within miniaturized polymeric devices. The idea of bioinspiration, in this case, presents itself in the sense that organs-on-a-chip seek to replicate physiological mechanisms existing in natural organs (such as shear stresses from fluid flow, mechanical stresses from cyclic stretching or compression), that would be difficult to mimic in static in-vitro cultures. For instance, a recently published lung-on-a-chip model 141–143 used microfabrication technology to engineer a transparent microdevice with two hollow microchannels separated by a permeable membrane. Each side of this membrane was seeded with either lung cells or endothelial cells, replicating the bi-layered composition of lung air-sacs where gas exchange occurs. Adjacent to this cell seeded membrane, two hollow channels where positioned to allow for cyclic stretching of the membrane with vacuum. The microdevice, which is the size of a computer stick, and was shown to replicate the physiological motion and cellular behavior of a living and breathing lung to levels that have not been possible with static cultures. Moreover, such miniaturized device allowed for real time observation of white blood cells migrating from the endothelial-lined channel through the permeable membrane, but only when bacteria was flushed on the “air” channel. This replicated precisely the immune response that would be observed in a typical lung infection.

Similar methods have now been adapted to engineer the gut-on-a-chip,144 liver-on-a-chip,145 bone marrow-on-a-chip,146 and several other organs, including examples of multiple organs on integrated breadboards simulating the body-on-a-chip.147 It is not hard to envision that a system replicating the pulp-dentin interface could be generated using such technology, and indeed our group has recently created prototypes for the tooth-on-a-chip and the periodontium-on-a-chip (Figure 6E–F), which we hope will soon allow for improved studies of the pulp-dentin interaction with bacteria, dental materials, and several other conditions pertaining to the interaction of dentin with the oral environment. This is a highly exciting avenue for future developments in bioinspired craniofacial tissue regeneration and biomanufacturing.

6. Conclusion

In summary, here we provide a comprehensive overview of the hierarchical organization of dentin, including its organic and inorganic building blocks. We highlight the relevance of the intrafibrillar mineral component to the mechanical properties of healthy and remineralized dentin, discuss the molecular to microscale organization of collagen type I, and describe the energy dissipation mechanisms regulated by non-collagenous proteins of the SIBLING family and proteoglycans. Lastly, we present recent data on bioinspired materials design and fabrication, as well as biomimetic tissue engineering and organs-on-a-chip to discuss how these emerging topics may influence the development of the dental materials of the future. Future dental materials can certainly benefit for the great progress in characterizing the dentin matrix on a nanoscale, and it is tangible that the interactions of novel dental materials with the dentin substrate will take into account several of the aspects discussed in this review and in the recent literature in the topic.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge funding from the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research and the National Institutes of Health (R01DE026170), the Australian Research Council (DP120104837), and the Medical Research Foundation of Oregon.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.St John KR. Dental clinics of North America. 2007;51(3):747–60. viii. doi: 10.1016/j.cden.2007.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen L, Shen H, Suh BI. Am J Dent. 2013;26(4):219–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wegst UG, Bai H, Saiz E, Tomsia AP, Ritchie RO. Nature materials. 2015;14(1):23–36. doi: 10.1038/nmat4089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ratner BD. Journal of dental education. 2001;65(12):1340–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Uskokovic V, Bertassoni LE. Materials (Basel) 2010;3(3):1674–1691. doi: 10.3390/ma3031674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bertassoni LE, Orgel JP, Antipova O, Swain MV. Acta Biomater. 2012;8(7):2419–33. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2012.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kruzic JJ, Ritchie RO. Journal of the mechanical behavior of biomedical materials. 2008;1(1):3–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2007.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Qin C, Baba O, Butler WT. Critical reviews in oral biology and medicine : an official publication of the American Association of Oral Biologists. 2004;15(3):126–36. doi: 10.1177/154411130401500302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Butler WT, Brunn JC, Qin C. Connect Tissue Res. 2003;44(Suppl 1):171–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Embery G, Hall R, Waddington R, Septier D, Goldberg M. Critical reviews in oral biology and medicine : an official publication of the American Association of Oral Biologists. 2001;12(4):331–49. doi: 10.1177/10454411010120040401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Staines KA, MacRae VE, Farquharson C. The Journal of endocrinology. 2012;214(3):241–55. doi: 10.1530/JOE-12-0143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Veis A, Dorvee JR. Calcif Tissue Int. 2013;93(4):307–15. doi: 10.1007/s00223-012-9678-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kalamajski S, Oldberg A. Matrix Biol. 2010;29(4):248–53. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2010.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boonrungsiman S, Gentleman E, Carzaniga R, Evans ND, McComb DW, Porter AE, Stevens MM. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2012;109(35):14170–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1208916109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mahamid J, Sharir A, Addadi L, Weiner S. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105(35):12748–53. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803354105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mahamid J, Aichmayer B, Shimoni E, Ziblat R, Li C, Siegel S, Paris O, Fratzl P, Weiner S, Addadi L. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107(14):6316–21. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914218107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Akiva A, Malkinson G, Masic A, Kerschnitzki M, Bennet M, Fratzl P, Addadi L, Weiner S, Yaniv K. Bone. 2015;75:192–200. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2015.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Akiva A, Kerschnitzki M, Pinkas I, Wagermaier W, Yaniv K, Fratzl P, Addadi L, Weiner S. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;138(43):14481–14487. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b09442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gower LB. Chem Rev. 2008;108(11):4551–627. doi: 10.1021/cr800443h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Niu LN, Jee SE, Jiao K, Tonggu L, Li M, Wang L, Yang YD, Bian JH, Breschi L, Jang SS, Chen JH, Pashley DH, Tay FR. Nature materials. 2016 doi: 10.1038/nmat4789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weiner S. J Struct Biol. 2008;163(3):229–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2008.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang Y, Azais T, Robin M, Vallee A, Catania C, Legriel P, Pehau-Arnaudet G, Babonneau F, Giraud-Guille MM, Nassif N. Nature materials. 2012;11(8):724–33. doi: 10.1038/nmat3362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lees S. Connect Tissue Res. 1987;16(4):281–303. doi: 10.3109/03008208709005616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Landis WJ. Journal of ultrastructure and molecular structure research. 1986;94(3):217–38. doi: 10.1016/0889-1605(86)90069-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nudelman F, Lausch AJ, Sommerdijk NA, Sone ED. J Struct Biol. 2013;183(2):258–69. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2013.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fratzl P, Fratzl-Zelman N, Klaushofer K. Biophysical journal. 1993;64(1):260–6. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(93)81362-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schroeder L, Frank RM. Cell Tissue Res. 1985;242(2):449–51. doi: 10.1007/BF00214561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tesch W, Eidelman N, Roschger P, Goldenberg F, Klaushofer K, Fratzl P. Calcif Tissue Int. 2001;69(3):147–57. doi: 10.1007/s00223-001-2012-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bonar LC, Lees S, Mook HA. Journal of molecular biology. 1985;181(2):265–70. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(85)90090-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nakabayashi N, Nakamura M, Yasuda N. J Esthet Dent. 1991;3(4):133–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8240.1991.tb00985.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fratzl P, Groschner M, Vogl G, Plenk H, Jr, Eschberger J, Fratzl-Zelman N, Koller K, Klaushofer K. Journal of bone and mineral research : the official journal of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. 1992;7(3):329–34. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650070313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kinney JH, Pople JA, Driessen CH, Breunig TM, Marshall GW, Marshall SJ. J Dent Res. 2001;80(6):1555–9. doi: 10.1177/00220345010800061501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kinney JH, Habelitz S, Marshall SJ, Marshall GW. J Dent Res. 2003;82(12):957–61. doi: 10.1177/154405910308201204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jager I, Fratzl P. Biophysical journal. 2000;79(4):1737–46. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76426-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gupta HS, Seto J, Wagermaier W, Zaslansky P, Boesecke P, Fratzl P. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2006;103(47):17741–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604237103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gupta HS, Wagermaier W, Zickler GA, Raz-Ben Aroush D, Funari SS, Roschger P, Wagner HD, Fratzl P. Nano letters. 2005;5(10):2108–11. doi: 10.1021/nl051584b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gupta HS, Messmer P, Roschger P, Bernstorff S, Klaushofer K, Fratzl P. Physical review letters. 2004;93(15):158101. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.93.158101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bertassoni LE, Habelitz S, Kinney JH, Marshall SJ, Marshall GW., Jr Caries research. 2009;43(1):70–7. doi: 10.1159/000201593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tay FR, Pashley DH. Biomaterials. 2008;29(8):1127–37. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cao CY, Mei ML, Li QL, Lo EC, Chu CH. International journal of molecular sciences. 2015;16(3):4615–27. doi: 10.3390/ijms16034615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tjaderhane L, Nascimento FD, Breschi L, Mazzoni A, Tersariol IL, Geraldeli S, Tezvergil-Mutluay A, Carrilho M, Carvalho RM, Tay FR, Pashley DH. Dent Mater. 2013;29(10):999–1011. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2013.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu Y, Luo D, Wang T. Small. 2016;12(34):4611–32. doi: 10.1002/smll.201600626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nurrohman H, Saeki K, Carneiro K, Chien YC, Djomehri S, Ho SP, Qin C, Marshall SJ, Gower LB, Marshall GW, Habelitz S. J Mater Res. 2016;31(3):321–327. doi: 10.1557/jmr.2015.406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fratzl P. Collagen: Structure and Function. Springer; US: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Miller A, Wray JS. Nature. 1971;230(5294):437–9. doi: 10.1038/230437a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sakaguchi RL, Powers JM. Craig’s Restorative Dental Materials. Elsevier; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nakabayashi N, Ashizawa M, Nakamura M. Quintessence Int. 1992;23(2):135–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nakabayashi N. Proceedings of the Finnish Dental Society. Suomen Hammaslaakariseuran toimituksia. 1992;88(Suppl 1):321–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nakabayashi N. Kokubyo Gakkai zasshi The Journal of the Stomatological Society, Japan. 1984;51(2):447–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cardoso MV, de Almeida Neves A, Mine A, Coutinho E, Van Landuyt K, De Munck J, Van Meerbeek B. Aust Dent J. 2011;56(Suppl 1):31–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.2011.01294.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vaidyanathan TK, Vaidyanathan J. Journal of biomedical materials research Part B, Applied biomaterials. 2009;88(2):558–78. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.31253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pioch T, Staehle HJ, Duschner H, Garcia-Godoy F. Am J Dent. 2001;14(4):252–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Habelitz S, Balooch M, Marshall SJ, Balooch G, Marshall GW., Jr J Struct Biol. 2002;138(3):227–36. doi: 10.1016/s1047-8477(02)00029-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Herchenhan A, Bayer ML, Svensson RB, Magnusson SP, Kjaer M. Developmental dynamics : an official publication of the American Association of Anatomists. 2013;242(1):2–8. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.23896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Goh KL, Holmes DF, Lu Y, Purslow PP, Kadler KE, Bechet D, Wess TJ. Journal of applied physiology. 2012;113(6):878–88. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00258.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Muthusubramaniam L, Peng L, Zaitseva T, Paukshto M, Martin GR, Desai TA. Journal of biomedical materials research Part A. 2012;100(3):613–21. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.33284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Berillis P, Emfietzoglou D, Tzaphlidou M. ScientificWorldJournal. 2006;6:1109–13. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2006.212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wess TJ. Advances in protein chemistry. 2005;70:341–74. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3233(05)70010-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Goh KL, Hiller J, Haston JL, Holmes DF, Kadler KE, Murdoch A, Meakin JR, Wess TJ. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2005;1722(2):183–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2004.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Orgel JP, Irving TC, Miller A, Wess TJ. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2006;103(24):9001–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502718103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bertassoni LE, Swain MV. Connect Tissue Res. 2016:1–10. doi: 10.1080/03008207.2016.1235566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Scott JE. Journal of anatomy. 1990;169:23–35. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Starborg T, Lu Y, Kadler KE, Holmes DF. Methods in cell biology. 2008;88:319–45. doi: 10.1016/S0091-679X(08)00417-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ottani V, Martini D, Franchi M, Ruggeri A, Raspanti M. Micron. 2002;33(7–8):587–96. doi: 10.1016/s0968-4328(02)00033-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hulmes DJ, Wess TJ, Prockop DJ, Fratzl P. Biophysical journal. 1995;68(5):1661–70. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(95)80391-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Raspanti M, Reguzzoni M, Protasoni M, Martini D. Biomacromolecules. 2011;12(12):4344–7. doi: 10.1021/bm201314e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Raspanti M, Congiu T, Guizzardi S. Matrix Biol. 2001;20(8):601–4. doi: 10.1016/s0945-053x(01)00174-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nakabayashi N, Kojima K, Masuhara E. Journal of biomedical materials research. 1982;16(3):265–73. doi: 10.1002/jbm.820160307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tay FR, Pashley DH. Am J Dent. 2003;16(1):6–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ottani V, Raspanti M, Ruggeri A. Micron. 2001;32(3):251–60. doi: 10.1016/s0968-4328(00)00042-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bella J, Berman HM. Journal of molecular biology. 1996;264(4):734–42. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bella J, Brodsky B, Berman HM. Structure. 1995;3(9):893–906. doi: 10.1016/S0969-2126(01)00224-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bella J, Eaton M, Brodsky B, Berman HM. Science. 1994;266(5182):75–81. doi: 10.1126/science.7695699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Chaussain C, Boukpessi T, Khaddam M, Tjaderhane L, George A, Menashi S. Frontiers in physiology. 2013;4:308. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2013.00308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Liu Y, Tjaderhane L, Breschi L, Mazzoni A, Li N, Mao J, Pashley DH, Tay FR. J Dent Res. 2011;90(8):953–68. doi: 10.1177/0022034510391799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Mazzoni A, Tjaderhane L, Checchi V, Di Lenarda R, Salo T, Tay FR, Pashley DH, Breschi L. Journal of dental research. 2015;94(2):241–51. doi: 10.1177/0022034514562833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Thompson JB, Kindt JH, Drake B, Hansma HG, Morse DE, Hansma PK. Nature. 2001;414(6865):773–6. doi: 10.1038/414773a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Fantner GE, Hassenkam T, Kindt JH, Weaver JC, Birkedal H, Pechenik L, Cutroni JA, Cidade GA, Stucky GD, Morse DE, Hansma PK. Nature materials. 2005;4(8):612–6. doi: 10.1038/nmat1428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Fantner GE, Oroudjev E, Schitter G, Golde LS, Thurner P, Finch MM, Turner P, Gutsmann T, Morse DE, Hansma H, Hansma PK. Biophysical journal. 2006;90(4):1411–8. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.069344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Gutsmann T, Fantner GE, Kindt JH, Venturoni M, Danielsen S, Hansma PK. Biophysical journal. 2004;86(5):3186–93. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(04)74366-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hansma PK, Fantner GE, Kindt JH, Thurner PJ, Schitter G, Turner PJ, Udwin SF, Finch MM. Journal of musculoskeletal & neuronal interactions. 2005;5(4):313–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Viani MB, Pietrasanta LI, Thompson JB, Chand A, Gebeshuber IC, Kindt JH, Richter M, Hansma HG, Hansma PK. Nature structural biology. 2000;7(8):644–7. doi: 10.1038/77936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Thompson JB, Hansma HG, Hansma PK, Plaxco KW. Journal of molecular biology. 2002;322(3):645–52. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)00801-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Adams J, Fantner GE, Fisher LW, Hansma PK. Nanotechnology. 2008;19(38):384008. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/19/38/384008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.He LH, Swain MV. Journal of the mechanical behavior of biomedical materials. 2008;1(1):18–29. doi: 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2007.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.He LH, Swain MV. Journal of biomedical materials research Part A. 2007;81(2):484–92. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.31051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.He LH, Swain MV. J Dent. 2007;35(5):431–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2006.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Prydz K. Biomolecules. 2015;5(3):2003–22. doi: 10.3390/biom5032003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Goldberg M, Takagi M. Histochem J. 1993;25(11):781–806. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Scott JE, Thomlinson AM. Journal of anatomy. 1998;192(Pt 3):391–405. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-7580.1998.19230391.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Gandhi NS, Mancera RL. Chemical biology & drug design. 2008;72(6):455–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0285.2008.00741.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Bertassoni LE, Swain MV. Journal of the mechanical behavior of biomedical materials. 2014;38:91–104. doi: 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2014.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Waddington RJ, Hall RC, Embery G, Lloyd DM. Matrix Biol. 2003;22(2):153–61. doi: 10.1016/s0945-053x(03)00019-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Goldberg M, Ono M, Septier D, Bonnefoix M, Kilts TM, Bi Y, Embree M, Ameye L, Young MF. Cells, tissues, organs. 2009;189(1–4):198–202. doi: 10.1159/000151370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Goldberg M, Septier D, Oldberg A, Young MF, Ameye LG. The journal of histochemistry and cytochemistry : official journal of the Histochemistry Society. 2006;54(5):525–37. doi: 10.1369/jhc.5A6650.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Orsini G, Ruggeri A, Jr, Mazzoni A, Papa V, Piccirilli M, Falconi M, Di Lenarda R, Breschi L. Int Endod J. 2007;40(9):669–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2007.01263.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Orsini G, Ruggeri A, Jr, Mazzoni A, Papa V, Mazzotti G, Di Lenarda R, Breschi L. Calcif Tissue Int. 2007;81(1):39–45. doi: 10.1007/s00223-007-9027-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Suppa P, Ruggeri A, Jr, Tay FR, Prati C, Biasotto M, Falconi M, Pashley DH, Breschi L. J Dent Res. 2006;85(2):133–7. doi: 10.1177/154405910608500204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Breschi L, Gobbi P, Lopes M, Prati C, Falconi M, Teti G, Mazzotti G. Journal of biomedical materials research Part A. 2003;67(1):11–7. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.10048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Breschi L, Lopes M, Gobbi P, Mazzotti G, Falconi M, Perdigao J. Journal of biomedical materials research. 2002;61(1):40–6. doi: 10.1002/jbm.10102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Bertassoni LE, Stankoska K, Swain MV. Micron. 2012;43(2–3):229–36. doi: 10.1016/j.micron.2011.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Stankoska K, Sarram L, Smith S, Bedran-Russo AK, Little CB, Swain MV, Bertassoni LE. Aust Dent J. 2016;61(3):288–97. doi: 10.1111/adj.12376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Antipova O, Orgel JP. PloS one. 2012;7(3):e32241. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Bertassoni LE, Swain MV. Connect Tissue Res. 2016 doi: 10.1080/03008207.2016.1235566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Bertassoni LE, Marshall GW. Scanning. 2009;31(6):253–8. doi: 10.1002/sca.20171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Bertassoni LE, Kury M, Rathsam C, Little CB, Swain MV. Journal of the mechanical behavior of biomedical materials. 2015;55:264–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2015.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Ho SP, Sulyanto RM, Marshall SJ, Marshall GW. J Struct Biol. 2005;151(1):69–78. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2005.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Xu T, Bianco P, Fisher LW, Longenecker G, Smith E, Goldstein S, Bonadio J, Boskey A, Heegaard AM, Sommer B, Satomura K, Dominguez P, Zhao C, Kulkarni AB, Robey PG, Young MF. Nature genetics. 1998;20(1):78–82. doi: 10.1038/1746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Grodzinsky AJ, Roth V, Myers E, Grossman WD, Mow VC. Journal of biomechanical engineering. 1981;103(4):221–31. doi: 10.1115/1.3138284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Scott JE. The Journal of physiology. 2003;553(Pt 2):335–43. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.050179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Haverkamp RG, Williams MA, Scott JE. Biomacromolecules. 2005;6(3):1816–8. doi: 10.1021/bm0500392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Ivancik J, Arola DD. Biomaterials. 2013;34(4):864–74. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.10.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Arola D, Reid J, Cox ME, Bajaj D, Sundaram N, Romberg E. Biomaterials. 2007;28(26):3867–75. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Bajaj D, Sundaram N, Nazari A, Arola D. Biomaterials. 2006;27(11):2507–17. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.11.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Arola DD, Reprogel RK. Biomaterials. 2006;27(9):2131–40. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Arola D, Reprogel RK. Biomaterials. 2005;26(18):4051–61. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Bajaj D, Nazari A, Eidelman N, Arola DD. Biomaterials. 2008;29(36):4847–54. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.08.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Bajaj D, Arola DD. Biomaterials. 2009;30(23–24):4037–46. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Mirkhalaf M, Dastjerdi AK, Barthelat F. Nature communications. 2014;5:3166. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Dimas LS, Buehler MJ. Soft Matter. 2014;10(25):4436–42. doi: 10.1039/c3sm52890a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Dimas LS, Buehler MJ. Bioinspiration & biomimetics. 2012;7(3):036024. doi: 10.1088/1748-3182/7/3/036024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Dimas LS, Bratzel GH, Eylon I, Buehler MJ. Advanced functional materials. 2013;23:4629–4638. [Google Scholar]

- 123.Langer R, Vacanti JP. Science. 1993;260(5110):920–6. doi: 10.1126/science.8493529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Khademhosseini A, Langer R, Borenstein J, Vacanti JP. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2006;103(8):2480–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507681102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Annabi N, Tsang K, Mithieux SM, Nikkhah M, Ameri A, Khademhosseini A, Weiss AS. Advanced functional materials. 2013;23(39) doi: 10.1002/adfm.201300570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Cheng CW, Niu B, Warren M, Pevny LH, Lovell-Badge R, Hwa T, Cheah KS. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2014;111(7):2596–601. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1313083111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Annabi N, Tamayol A, Uquillas JA, Akbari M, Bertassoni LE, Cha C, Camci-Unal G, Dokmeci MR, Peppas NA, Khademhosseini A. Advanced materials. 2014;26(1):85–123. doi: 10.1002/adma.201303233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Acharya G, Shin CS, McDermott M, Mishra H, Park H, Kwon IC, Park K. Journal of controlled release : official journal of the Controlled Release Society. 2010;141(3):314–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2009.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Nikkhah M, Edalat F, Manoucheri S, Khademhosseini A. Biomaterials. 2012;33(21):5230–46. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.03.079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Baker BM, Trappmann B, Stapleton SC, Toro E, Chen CS. Lab on a chip. 2013;13(16):3246–52. doi: 10.1039/c3lc50493j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Murphy SV, Atala A. Nature biotechnology. 2014;32(8):773–85. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Bertassoni LE, Cecconi M, Manoharan V, Nikkhah M, Hjortnaes J, Cristino AL, Barabaschi G, Demarchi D, Dokmeci MR, Yang Y, Khademhosseini A. Lab on a chip. 2014;14(13):2202–11. doi: 10.1039/c4lc00030g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Barabaschi GD, Manoharan V, Li Q, Bertassoni LE. Advances in experimental medicine and biology. 2015;881:79–94. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-22345-2_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Miller JS, Stevens KR, Yang MT, Baker BM, Nguyen DH, Cohen DM, Toro E, Chen AA, Galie PA, Yu X, Chaturvedi R, Bhatia SN, Chen CS. Nature materials. 2012;11(9):768–74. doi: 10.1038/nmat3357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Bertassoni LE, Cardoso JC, Manoharan V, Cristino AL, Bhise NS, Araujo WA, Zorlutuna P, Vrana NE, Ghaemmaghami AM, Dokmeci MR, Khademhosseini A. Biofabrication. 2014;6(2):024105. doi: 10.1088/1758-5082/6/2/024105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Ma X, Qu X, Zhu W, Li YS, Yuan S, Zhang H, Liu J, Wang P, Lai CS, Zanella F, Feng GS, Sheikh F, Chien S, Chen S. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2016;113(8):2206–11. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1524510113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Kang HW, Lee SJ, Ko IK, Kengla C, Yoo JJ, Atala A. Nature biotechnology. 2016;34(3):312–9. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Obregon F, Vaquette C, Ivanovski S, Hutmacher DW, Bertassoni LE. J Dent Res. 2015;94(9 Suppl):143S–52S. doi: 10.1177/0022034515588885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Huh D, Torisawa YS, Hamilton GA, Kim HJ, Ingber DE. Lab on a chip. 2012;12(12):2156–64. doi: 10.1039/c2lc40089h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Bhatia SN, Ingber DE. Nature biotechnology. 2014;32(8):760–72. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Huh D, Kim HJ, Fraser JP, Shea DE, Khan M, Bahinski A, Hamilton GA, Ingber DE. Nature protocols. 2013;8(11):2135–57. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2013.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Huh D, Leslie DC, Matthews BD, Fraser JP, Jurek S, Hamilton GA, Thorneloe KS, McAlexander MA, Ingber DE. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4(159):159ra147. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3004249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Huh D, Matthews BD, Mammoto A, Montoya-Zavala M, Hsin HY, Ingber DE. Science. 2010;328(5986):1662–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1188302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Kim HJ, Ingber DE. Integr Biol (Camb) 2013;5(9):1130–40. doi: 10.1039/c3ib40126j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Starokozhko V, Groothuis GM. Expert opinion on drug metabolism & toxicology. 2016 doi: 10.1080/17425255.2017.1246537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Torisawa YS, Spina CS, Mammoto T, Mammoto A, Weaver JC, Tat T, Collins JJ, Ingber DE. Nature methods. 2014;11(6):663–9. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Skardal A, Shupe T, Atala A. Drug discovery today. 2016;21(9):1399–411. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2016.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]