BACKGROUND

I saw Mr. D for follow-up after a hospitalization for respiratory failure from methadone use. He had a history of chronic pain, polysubstance abuse, depression, obstructive sleep apnea, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). I transitioned him from methadone to moderate-dose oxycodone. The next month, he was readmitted with respiratory depression. I then recommended against opioid therapy given his multiple risk factors, but he was adamant about continuing opioid treatment. We had multiple strained conversations over the following weeks, and the tension between us escalated. I was concerned that our relationship was damaged and that we were not addressing his other medical problems.

The alarming rise in opioid-related deaths over the past decade, along with mounting evidence of an unfavorable balance between the benefits and harms of chronic opioids, have led to widespread calls from a range of stakeholders, including the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the US Surgeon General, physician professional societies, patient advocacy groups, politicians, and the media, for clinicians to reexamine the use of opioid therapy for chronic pain.1 Primary care providers (PCPs) are at the epicenter of the opioid epidemic. Discussing opioid use, however, can be a source of significant distress for both patients and providers. Concerns about undertreated pain, safety, and opioid misuse can cause both parties to feel anxious and unfairly judged, eroding trust and leading to adversarial interactions.2

As recent residency graduates starting careers in primary care, we (CZ, KM) have felt the frustration of opioid management in our VA clinic, which includes 54 internal medicine residents and 14 attending physicians. We serve approximately 5000 veterans, about 10 % of whom are prescribed chronic opioids (defined as more than 90 days). We noted that residents in particular were struggling with opioid management, despite receiving formal didactics on chronic pain and having resources to help guide decision-making. Our sense was that, despite knowing what we should do for patients on opioids, many of us felt stuck in difficult patient interactions. We identified a “support gap” rather than a “knowledge gap,” and wanted to address the burden of opioid management in our clinic before it led to more distress and burnout. Informal conversations with other faculty and residents led to the idea of a peer-based “controlled substance review group” (CSRG) that would provide guidance regarding opioid prescribing, patient communication, and alternative pain management strategies. We suspected that other resident clinics have created opioid review groups, but did not find descriptions of similar interventions in the literature.

IMPLEMENTATION AND INITIAL OUTCOMES

In order to gauge interest, we conducted an anonymous survey asking clinic staff whether they were in favor of a CSRG. Of 49 respondents, 46 said that they “strongly agreed.” Comments ranged from fully endorsing the idea to concerns about interference with the patient–provider relationship (e.g., “I would tread lightly on disrupting long continuity relationships in which the opioid plan seems to be working.”).

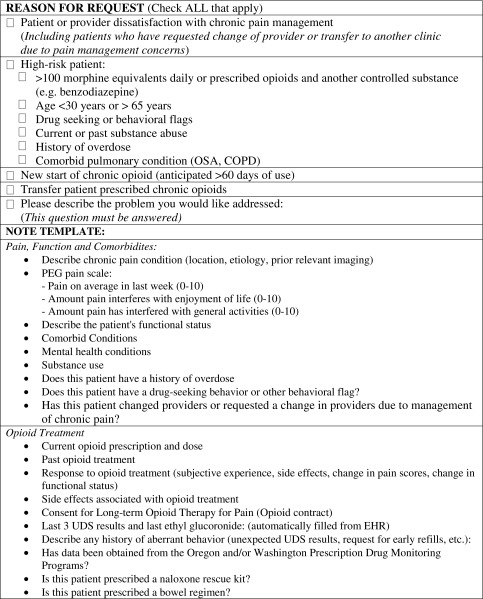

Based on this feedback, as well as our primary goal of offering clinicians support with difficult patient interactions, we chose to offer a consultation service for PCPs to use at their discretion, rather than proactively identify high-risk cases. We invited clinic staff to participate in planning meetings, where we defined the goals of the CSRG. Two residents drafted a project overview that we shared with all clinic staff. We partnered with our information technology group to develop a new electronic consult process and created a standardized Chronic Pain Assessment Note for consulting providers to complete (Table 1). This template prompts a review of the patient’s chronic pain history, treatment history, and risk factors for opioid therapy including comorbid mental health conditions, substance use, prior aberrant urine drug screens, early refills, and receipt of opioids from multiple prescribers (from state prescription drug monitoring programs). It also includes two standardized assessment tools: the Diagnosis, Intractability, Risk, Efficacy (DIRE)3 score, and the Opioid Risk Tool (ORT).4

Table 1.

Controlled Substance Review Group Consult and Note Template

We began meeting in October 2015, and currently meet weekly during the lunch hour to discuss two cases. Our members include 4–5 attending physicians, 1–2 resident physicians, a nurse, a pharmacist, a social worker, a mental health provider, and a pain psychologist. The referring provider, accompanied by other members of the patient’s care team, attends the CSRG meeting and presents the case using the Chronic Pain Assessment Note. The group then discusses the risks and benefits of opioid therapy in the context of the patient’s pain condition, functional status, and comorbidities. After reaching a consensus regarding whether opioids should be continued, stopped, or tapered, the group reviews alternative pain treatment strategies. We often identify untreated or undertreated mental health conditions, including undiagnosed substance use disorders. Having representatives from several disciplines helps with referrals to resources outside of primary care, including mental health, our pain subspecialty clinic, or addiction treatment services. We conclude by helping the referring provider with communication strategies, including specific phrases to use with patients. This discussion and the group’s recommendations are summarized in a consult note in the patient’s chart.

During the first year, the CSRG reviewed 54 cases, 44 of which were referrals from residents. Patients were a mean 61 years of age (range 26–84), and most were men (52/54) and had a primary diagnosis of chronic non-cancer pain (53/54). Providers consulted the CSRG for help with opioid management in high-risk patients (26/54) due to patient dissatisfaction with the treatment plan (13/54) and for review of new or transfer patients on opioids (15/54). Following consultation with the group, opioids were discontinued in 29/54 cases, not increased in 3/54 cases, not started in 13/54, continued in 8/54, and started in 1/54. Implementation of the CSRG recommendations has resulted in approximately 1550 fewer morphine milligram equivalents being prescribed by our clinic every day.

The CSRG serves several roles. First, it serves a clinical role by providing evidence-based recommendations in line with current guidelines. Second, it serves a supportive role by giving providers a forum to discuss their challenging cases and receive validation of their concerns. Finally, it serves as a forum for interdisciplinary members to convey their perspectives on chronic pain management, resulting in improved care coordination and a shared practice model. Follow-up survey comments included, “Having back-up for my decision not to prescribe opioids made me more confident in my decision and relieved me of some of the guilt I had for my patient’s dissatisfaction,” “It [the CSRG] provided me with resources to help facilitate the transition off opioids and alternative ways to help decrease his pain,” and “The group’s recommendations empowered me to do the right thing for my patient.”

CHALLENGES AND NEXT STEPS

Our group faced challenges in its development. First, most of the group participants did not have specific training in chronic pain management and initially felt ill-prepared to provide recommendations. We (CZ, KM) sought out self-directed learning opportunities and recruited a senior provider with expertise in this field to attend our meetings. Learning by doing, we developed more confidence in our assessments and recommendations. Second, many of the patients we reviewed met criteria for opioid use disorder. We recognize that some patients may not accept this diagnosis and that referral options are limited. Improved recognition of opioid use disorder among our patient population has led to separate initiatives to expand addiction treatment services, including the potential to start prescribing buprenorphine within the primary care setting. Third, we currently rely upon donated time from our providers and staff. This option may not be feasible in other practice settings and may limit adoption of our approach. Our hope is that widespread adoption of interventions like the CSRG and associated research on their impact on physician burnout, quality of care, and patient outcomes may encourage institutional support and reimbursement models that recognize their added value. Fourth, the Chronic Pain Assessment Note is time-consuming for referring providers, and some sections, such as the Opioid Risk Tool, are not consistently completed, limiting their use. However, even if incomplete, the note prompts a critical review of the patient’s history, a necessary step in ensuring safe prescribing practices. Finally, while a significant proportion of residents have consulted our group, most attending providers have not. We suspect that this is because attending providers feel more comfortable managing challenging cases or are reluctant to change their opioid prescribing patterns.

I referred Mr. D to our CSRG. The group identified several risk factors to continued opioid prescribing and noted that his functional status had remained poor despite years of opioid therapy. They recommended discontinuing opioids and suggested several non-pharmacologic interventions, including referral to mental health. At our next visit, I told Mr. D about the group’s recommendations, and while he disagreed, having the CSRG assessment eased the tension during our visits and allowed us to focus on his other problems.

Addressing the opioid epidemic will require a multifaceted approach. Interventions like the CSRG are an important means of helping providers on the frontline, where decisions about opioid prescribing are negotiated and contested. By engaging residents in designing and implementing this innovation, we hope to have empowered them to tackle this and other public health and patient safety issues in their future practices. Moving forward, our goals include engaging more of our providers, expanding our options to treat opioid use disorder, and assessing the impact of the CSRG on patient–provider relationships. We hope that our experience can help other primary care clinics struggling with this issue.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain—United States, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65:1–49. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.rr6501e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Matthias MS, Parpart AL, Nyland KA, et al. The patient–provider relationship in chronic pain care: providers’ perspectives. Pain Med. 2010;11:1688–1697. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2010.00980.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Belgrade MJ, Schamber CD, Lindgren BR. The DIRE score: predicting outcomes of opioid prescribing for chronic pain. J Pain. 2006;7(9):671–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2006.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jones T, Passik SD. A comparison of methods of administering the opioid risk tool. J Opioid Manag. 2010;7(5):347–51. doi: 10.5055/jom.2011.0075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]