Abstract

Background

The Physician Payments Sunshine Act, part of the Affordable Care Act, requires pharmaceutical and medical device firms to report payments they make to physicians and, through its Open Payments program, makes this information publicly available.

Objective

To establish estimates of the exposure of the American patient population to physicians who accept industry payments, to compare these population-based estimates to physician-based estimates of industry contact, and to investigate Americans’ awareness of industry payments.

Design

Cross-sectional survey conducted in late September and early October 2014, with data linkage of respondents’ physicians to Open Payments data.

Participants

A total of 3542 adults drawn from a large, nationally representative household panel.

Main Measures

Respondents’ contact with physicians reported in Open Payments to have received industry payments; respondents’ awareness that physicians receive payments from industry and that payment information is publicly available; respondents’ knowledge of whether their own physician received industry payments.

Key Results

Among the 1987 respondents who could be matched to a specific physician, 65% saw a physician who had received an industry payment during the previous 12 months. This population-based estimate of exposure to industry contact is much higher than physician-based estimates from the same period, which indicate that 41% of physicians received an industry payment. Across the six most frequently visited specialties, patient contact with physicians who had received an industry payment ranged from 60 to 85%; the percentage of physicians with industry contact in these specialties was much lower (35–56%). Only 12% of survey respondents knew that payment information was publicly available, and only 5% knew whether their own doctor had received payments.

Conclusions

Patients’ contact with physicians who receive industry payments is more prevalent than physician-based measures of industry contact would suggest. Very few Americans know whether their own doctor has received industry payments or are aware that payment information is publicly available.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s11606-017-4012-3) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

KEY WORDS: financial conflicts of interest, physician-industry relationships, industry payments, physician payments sunshine act, open payments

INTRODUCTION

As part of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA), pharmaceutical and medical device manufacturers are now required to report gifts and payments that they make to health care providers. In particular, in a section known as the Physician Payments Sunshine Act, the law states that beginning August 2013, manufacturers must regularly report to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) payments and transfers of value that they make to physicians.1 , 2 CMS makes this information available to the public through its Open Payments website.3

This legal provision was motivated in part by concerns that industry payments could lead physicians to make decisions that were not in the best interest of their patients, and that patients ought to be able to choose physicians and make medical decisions with this knowledge about industry payments in mind.1 , 2 , 4 The impact of the Sunshine Act, however, will depend on how aware Americans are of the prevalence of industry payments, whether their own physicians receive payments, and potential biasing effects of these payments.5 – 14 In addition to affecting patient decision-making, public disclosure of payments could also deter physicians from accepting payments from industry.2 , 15 Accurately estimating the scope and scale of industry payments and monitoring the effects of payment disclosure will be important as CMS refines implementation of its Open Payments reporting system.

Previous research on the prevalence of physician payments has relied on surveys of physicians, or more recently—with the availability of Open Payments and state-mandated disclosure of industry payments—estimates of the percentage of physicians reported as having received payments. A 2004 survey of physicians in six specialties found high rates of self-reported industry contact; 84% of physicians reported, for example, having received free food and drink.16 More recent studies using Open Payments data have found the prevalence of industry payments among physicians to be around 40%, with variation across specialties ranging from 20% (pathology) to 80–90% (cardiology and orthopaedics).17 – 22

These estimates provide information about industry contact among physicians, but may give a partial or misleading picture of the reach of industry payments in relation to patients. As Figure 1 schematically illustrates, even if only a minority of physicians receive industry payments, it is possible for much higher percentages of patients to be regularly exposed to physicians who receive these payments. This could happen if physicians who accept industry payments care for more patients than those who do not accept payments, or if patients frequently visit physicians in specialties that have more industry contact, even though these specialists constitute a small part of the medical profession. Distinguishing between patient exposure to physicians with industry contact and physician exposure to industry is important, because the reach of industry influence in clinical care could be much greater than the prevalence of payments among physicians would suggest.

Figure 1.

Industry reach among patients versus industry reach among physicians.

To our knowledge, no studies have taken a population-based approach to estimating the reach of industry payments. To investigate patient-level exposure and gather background information on patients’ knowledge of industry payments, we fielded a nationally representative survey of Americans shortly before the first release of the Open Payments data in September 2014. We asked respondents about their awareness of and knowledge about industry payments, and about the physician they saw most frequently during the previous 12 months. We linked these named physicians to the newly released Open Payments data to ascertain how frequently patients saw physicians who accepted industry payments. We then compared patient-based industry exposure measures to physician-based measures.

This survey of American adults provides information on patient-level exposure to physicians who accept industry payments and describes Americans’ awareness of industry payments. Because it was fielded shortly before the Open Payments data release, the survey also establishes baseline estimates of the reach of industry payments in the US population prior to the public dissemination of payment information.

METHODS

Sample

A sample of 7718 adults aged 18 and older residing in the USA was selected from KnowledgePanel® (KP), a large, nationally representative household panel (including non-Internet households) maintained by the research firm GfK. Details on survey methodology are provided in online Appendices S1 and S2. The study protocol was reviewed by the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board.

Survey Design

GfK administered a 6-min online survey. Respondents were asked about their knowledge of industry payments in general, whether they were aware this information was publicly available, and if they knew whether the physician they had seen most frequently during the past 12 months (who they were asked to name) had received industry payments. GfK provided information, collected within the previous 6 months, on respondents’ sociodemographic and self-reported health characteristics.

Survey Fielding

Surveys were fielded in late September and early October 2014. Almost all surveys (94%) were completed by the Open Payments data release date of September 30, 2014.

Physician Matching

In the survey, approximately 84% of respondents (2972/3542) named a specific health care provider that they had seen most frequently in the past 12 months. Using manual matching and probabilistic matching algorithms (details in online Appendix S1), we matched named providers to those assigned a National Provider Identifier (NPI) and listed in the CMS National Plan and Provider Enumeration System (NPPES). Combined, the two algorithms were able to match 1971 physicians named by 1987 respondents (some respondents named the same physician). Overall, 66% of the 3542 respondents could be matched to an NPI-registered provider and 56% could be matched to an NPI-registered physician. We call the subgroup of respondents with matched physicians our verified sample.

Open Payments Data

Using NPI identifiers, we then matched the physicians named by respondents to providers reported to have received payments in the Open Payments system. We focused on the subset of payments classified as "general payments," which included payments related to consulting, education, entertainment, food and beverage, gifts, honoraria, royalties or licenses, serving as faculty or speaker in continuing education or other programs, and travel and lodging.

Because respondents were asked about the doctor they had seen most frequently in the past 12 months, we focused on payments made to providers between September 1, 2013 and August 30, 2014, the 12-month period preceding the survey.

Physician-Based Measures of Industry Contact

To measure physician contact with industry, we calculated the percentage of physicians overall and in each of six major specialties—family medicine, internal medicine, obstetrics and gynecology, orthopaedic surgery, pediatrics, and psychiatry and neurology—who had been reported in Open Payments to have received an industry payment between September 1, 2013, and August 30, 2014. The total number of physicians (overall and in each specialty) was obtained from counts of physicians listed in the NPPES NPI Registry.

Statistical Analysis

We used bivariate analyses to examine associations between respondent characteristics and (1) awareness of industry payments, and (2) whether the respondent’s named physician had received an industry payment. Respondent characteristics included sociodemographic characteristics (gender, age, education, race/ethnicity, household income, whether they resided in an urban area and/or a Sunshine state, employment status, and type of health insurance), and health status (previous diagnoses of chronic conditions, cancer, stroke or heart attack, or mental health disorders). All analyses used GfK-constructed weights that adjusted for non-coverage, nonresponse, and oversampling. Because of the weighting, we applied the Rao-Scott correction of the χ 2 statistic to test for independence. To account for multiple testing of 13 respondent characteristics, we report the Bonferroni correction for statistical significance at α = 0.01 and α = 0.05. All analyses were conducted using Stata 14 software (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

Sample Characteristics

The survey completion rate was 45.9% (3542/7718), higher than average for web and telephone public opinion surveys and within the norm for paper-based surveys.23 – 25 Table 1 presents weighted and unweighted sample characteristics. In the remainder of the paper, we report weighted results unless otherwise specified.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics

| Number | Unweighted percentage | Weighted percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Female | 1745 | 49.3% | 51.8% |

| Male | 1797 | 50.7% | 48.2% |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| White | 2575 | 72.7% | 65.6% |

| Hispanic | 381 | 10.8% | 15.2% |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 344 | 9.7% | 11.5% |

| Other | 242 | 6.8% | 7.8% |

| Age (years)* | |||

| ≤20 | 98 | 2.8% | 4.1% |

| 21–30 | 537 | 15.2% | 19.1% |

| 31–40 | 497 | 14.0% | 15.7% |

| 41–50 | 515 | 14.5% | 15.2% |

| 51–60 | 782 | 22.1% | 20.8% |

| 61+ | 1113 | 31.4% | 25.1% |

| Education | |||

| Less than high school | 323 | 9.1% | 12.4% |

| High school graduate | 1077 | 30.4% | 29.7% |

| Some college | 1049 | 29.6% | 28.8% |

| College graduate | 1093 | 30.9% | 29.2% |

| Marital status | |||

| Married/cohabiting | 2190 | 61.8% | 60.0% |

| Single | 1352 | 38.2% | 40.0% |

| Household income | |||

| $0–24,999 | 699 | 19.7% | 17.9% |

| $25,000–49,999 | 807 | 22.8% | 22.5% |

| $50,000–74,999 | 671 | 18.9% | 18.4% |

| $75,000–99,999 | 487 | 13.8% | 15.4% |

| $100,000+ | 878 | 24.8% | 25.8% |

| Household size | |||

| 1 | 735 | 20.8% | 19.9% |

| 2 | 1384 | 39.1% | 36.1% |

| 3 | 608 | 17.2% | 18.2% |

| 4+ | 815 | 23.0% | 25.8% |

| Employment | |||

| Employed for pay | 1710 | 48.3% | 50.5% |

| Self-employed | 241 | 6.8% | 6.8% |

| Retired | 827 | 23.4% | 18.7% |

| Not working - disability/other | 261 | 7.4% | 7.2% |

| Urban/rural | |||

| Urban | 3013 | 85.1% | 84.4% |

| Rural | 529 | 14.9% | 15.6% |

| Resides in state with Sunshine Law | |||

| No | 3231 | 91.2% | 96.0% |

| Yes | 311 | 8.8% | 4.0% |

| Self-rated health† | |||

| Excellent | 474 | 13.5% | 14.1% |

| Good | 2139 | 61.0% | 60.9% |

| Fair | 759 | 21.7% | 21.4% |

| Poor | 132 | 3.8% | 3.5% |

| Diagnoses of health conditions‡ | |||

| Diagnosis of chronic condition§ | 2100 | 59.8% | 54.9% |

| Diagnosis of mental health disorder | 660 | 18.8% | 18.3% |

| Diagnosis of cancer | 370 | 10.5% | 8.7% |

| Diagnosis of stroke or MI | 146 | 4.2% | 3.5% |

| Health insurance (not mutually exclusive) | |||

| Employer coverage | 1968 | 55.6% | 56.9% |

| Medicare | 968 | 27.3% | 23.1% |

| Medicaid | 416 | 11.7% | 12.1% |

| Other | 329 | 9.3% | 8.7% |

| No insurance | 577 | 16.3% | 17.8% |

| Sample size | 3542 | ||

*Age: range 18–94, mean 47.2, median 47

† n = 3504 respondents

‡ n = 3513 respondents

§Chronic conditions include acid reflux, asthma, COPD, atrial fibrillation, chronic pain, cystic fibrosis, diabetes, epilepsy, eye disease, gout, heart disease, hepatitis C, hypertension, high cholesterol, HIV, kidney disease, multiple sclerosis, osteoarthritis, osteoporosis, rheumatoid arthritis, sleep disorder

Physician-Based vs. Population-Based Estimates of Industry Payments Reach

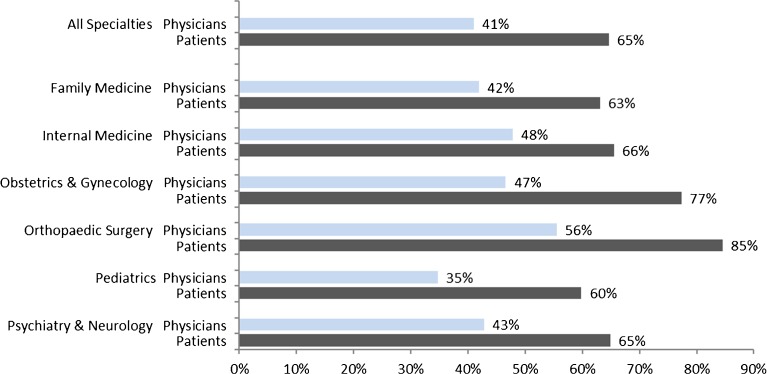

Figure 2 shows the percentage of physicians, among all NPI-registered physicians, reported in Open Payments to have received industry payments in the past year, compared to the percentage of survey respondents whose physician was reported in Open Payments. Consistent with previous studies using physician-based measures, 41% of physicians had received an industry payment of some type. Yet in the survey subgroup for which we could verify physician identity (“verified sample”), a higher proportion—about 65%—of respondents had seen a physician who had accepted an industry payment.

Figure 2.

Percentage of physicians who received payments and percentage of respondents in the verified sample whose physician received payments in 2013–2014.

We also compared industry contact measures for various medical specialties. Figure 2 reports population-based and physician-based industry contact measures for the six specialty areas most frequently encountered by survey respondents. In the most frequently visited specialty, family practice, 42% of NPI-registered physicians had received industry payments, but 63% of verified sample respondents who had seen a family medicine physician saw a doctor who had received payments. Forty-seven percent of physicians specializing in obstetrics and gynecology had received payments, but almost double that percentage—77%—of respondents who named an obstetrician/gynecologist as their most frequently visited physician named a doctor who had received payments. This pattern of patient exposure to higher levels of industry payments compared to physician-based measures of industry payments is consistent across all of the major specialties.

Median industry payment amounts were higher among physicians identified by survey respondents than among all physicians listed in Open Payments (Table 2). Across all specialties, the median payment received by physicians named by respondents was more than 2.5 times as high as the median among all Open Payments physicians ($510 vs. $193). Similarly, for the six specialties most frequently visited by survey respondents, the median payment amounts received by physicians named by respondents were higher than the median amounts received among all Open Payments physicians in these same specialties. Thus, the physicians that patients frequently visited were more likely to have received industry payments and, when they received payments, received amounts greater than were typical of physicians reported in Open Payments.

Table 2.

Median Dollar Amount of Payments to Physicians in Open Payments and to Physicians Named in Survey

| Open Payments | Survey | |

|---|---|---|

| All specialties | $193 | $510 |

| Family medicine | $183 | $489 |

| Internal medicine | $304 | $630 |

| Obstetrics & gynecology | $150 | $197 |

| Orthopaedic surgery | $422 | $510 |

| Pediatrics | $92 | $205 |

| Psychiatry & neurology | $230 | $345 |

Public Awareness and Knowledge of Industry Payments

Despite respondents’ extensive contact with physicians who received industry payments, public awareness of industry payments was limited. Overall, 45% of respondents reported that they were aware of industry payments being made to physicians. Twelve percent were aware that payment information was publicly available. Only 5% of respondents reported knowing whether their own doctor had received payments.

We compared actual Open Payments data with respondents’ beliefs about payments their doctors had received. Among the 74 (of 3542) respondents who reported knowing whether their doctor had received payments and provided a physician’s name that we could verify, most (70% unweighted) believed that their doctor had not received payments in the past 12 months. Of these, 41% were incorrect in that belief: Open Payments data indicated that their physician had actually accepted an industry payment.

Bivariate Analyses of Public Awareness and Physician Receipt of Payments

In Table 3, we report results from bivariate analyses examining relationships between respondent characteristics and the proportion of respondents who were aware of industry payments (second column), and whether their physician had received an industry payment (fourth column). Because we conducted 13 different comparisons, the appropriate p values—Bonferroni-corrected for multiple comparisons—are 0.0008 for α = 0.01 and 0.0038 for α = 0.05.

Table 3.

Awareness of Industry Payments and Visits to a Physician Who Received Payments, by Demographic Group

| % Aware of Physician Payments* | p value | % Named physician who received payment† | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.0001‡ | 0.5541 | ||

| Female | 45% | 65% | ||

| Male | 51% | 64% | ||

| Race/ethnicity | <0.0001‡ | 0.4123 | ||

| White | 52% | 65% | ||

| Hispanic | 36% | 59% | ||

| Black, non-Hispanic | 30% | 65% | ||

| Other | 50% | 68% | ||

| Age (years) | <0.0001‡ | 0.1432 | ||

| ≤20 | 30% | 68% | ||

| 21–30 | 39% | 56% | ||

| 31–40 | 50% | 65% | ||

| 41–50 | 49% | 66% | ||

| 51–60 | 50% | 65% | ||

| 61+ | 52% | 67% | ||

| Education | <0.0001‡ | 0.2450 | ||

| Less than high school | 33% | 69% | ||

| High school graduate | 35% | 67% | ||

| Some college | 47% | 62% | ||

| College graduate | 65% | 63% | ||

| Household Income | <0.0001‡ | 0.7976 | ||

| $0–24,999 | 31% | 63% | ||

| $25,000–49,999 | 42% | 65% | ||

| $50,000–74,999 | 47% | 63% | ||

| $75,000–99,999 | 50% | 68% | ||

| $100,000+ | 61% | 64% | ||

| Employment | <0.0001‡ | 0.8209 | ||

| Employed for pay | 51% | 65% | ||

| Self-employed | 55% | 62% | ||

| Retired | 51% | 65% | ||

| Not working - disability | 34% | 68% | ||

| Not working - other | 35% | 62% | ||

| Urban/rural | 0.0038§ | 0.5551 | ||

| Urban | 49% | 66% | ||

| Rural | 42% | 64% | ||

| Resides in state with Sunshine Law | 0.0001‡ | <0.0001‡ | ||

| No | 47% | 66% | ||

| Yes | 58% | 34% | ||

| Diagnosis of chronic condition‖ | <0.0001‡ | 0.1949 | ||

| No | 44% | 62% | ||

| Yes | 51% | 66% | ||

| Diagnosis of mental health disorder | 0.0939 | 0.0523 | ||

| No | 47% | 64% | ||

| Yes | 51% | 69% | ||

| Diagnosis of cancer | 0.0002‡ | 0.7871 | ||

| No | 47% | 65% | ||

| Yes | 58% | 64% | ||

| Diagnosis of stroke or MI | 0.0729 | 0.6351 | ||

| No | 47% | 65% | ||

| Yes | 56% | 67% | ||

| Type of health insurance | <0.0001‡ | 0.0292 | ||

| HMO | 47% | 60% | ||

| PPO | 57% | 67% | ||

| Fee-for-service | 54% | 70% | ||

| Not sure | 33% | 65% |

*n = 3117 respondents

† n = 1855 respondents (verified sample only)

‡Significant at 0.01 level with Bonferroni correction (0.01/13 = 0.0008)

§Significant at 0.05 level with Bonferroni correction (0.05/13 = 0.0038)

‖Chronic conditions include acid reflux, asthma, COPD, atrial fibrillation, chronic pain, cystic fibrosis, diabetes, epilepsy, eye disease, gout, heart disease, hepatitis C, hypertension, high cholesterol, HIV, kidney disease, multiple sclerosis, osteoarthritis, osteoporosis, rheumatoid arthritis, sleep disorder

HMO health maintenance organization, PPO preferred provider organization

Respondents with more education and higher income were more likely to be aware of physician payments than those with lower education and income (p < 0.0001 for both). Individuals who had been diagnosed with chronic conditions or cancer were significantly more likely to be aware of physician payments (p < 0.0001 and p = 0.0002, respectively). In addition, respondents living in Massachusetts, Minnesota, and Vermont-- states that had pre-existing laws requiring public disclosure of physician payments (“Sunshine states”)-- had a greater awareness of physician payments (58% vs. 47%, p < 0.0001).

In contrast, there were few significant bivariate associations between respondents’ demographic or health characteristics and whether their physician had received industry payments. We did find, however, that a far lower percentage of respondents in Sunshine states reported seeing a physician who received payments, compared to respondents in non-Sunshine states (34% vs. 66%, p < 0.0001).

DISCUSSION

About two thirds of American adults in our national survey saw a physician in 2013–2014 who had accepted payments from industry within the past year, indicating that the reach of industry payments into patient care is extensive.

To our knowledge, this is the first nationally representative study examining the prevalence of industry payments among the general patient population. Prior studies using payment data have calculated the percentage of physicians, overall and by specialty, who received industry payments.17 – 22 Our physician-based estimates of industry contact, based on the percentage of physicians receiving industry payments, were similar to those in these earlier studies, but we found that these estimates understated the prevalence of patient contact with industry. Although 4 of every 10 physicians had received a payment during the 12 months under study, almost 7 of 10 respondents were seen over the same period by a physician who had received a payment.

The physicians whom patients visited also tended to have received unusually high payments. The median payment received by these physicians was 1.2–2.7 times greater, depending on the specialty, than the median payment among all physicians in Open Payments in the same specialty.

These findings suggest that although physicians who accept industry payments are in the minority, they are caring for a very substantial portion of America’s adult patient population. These estimates are, moreover, likely to be an underestimate of Americans’ exposure to doctors with industry ties. Although we did not examine the professional or social status of recipient physicians, drug and device companies tend to pursue relationships with “key opinion leaders” in medicine because of these leaders’ potential to influence the clinical practice of others, even those who themselves do not accept industry payments.26 Our analysis also did not include research payments, an additional route of industry contact for physicians.

Despite the broad reach of industry payments and substantial previous literature documenting patients’ interest in and concern about their physicians’ conflicts of interest,8 few respondents knew about the contact that their physicians had with industry. Only 12% had heard about industry payments, and only 5% knew whether their own doctor had received payments. We anticipate that these percentages will increase as Open Payments becomes more widely known and accessed.

We found that the proportion of respondents who saw physicians who received industry payments was about twice as high in states that had not made payment data public (66%) than in the few states that had (34%). Our cross-sectional data do not allow us to pinpoint the causes of this difference—whether payment disclosure affected patients’ choice of physicians, leading them to choose physicians without industry ties, or perhaps acted as a deterrent for some doctors, leading them to shun industry ties—but the difference in the prevalence of industry payments across these two types of states is striking and will be important to monitor with the expansion of payment disclosure at a national level.

Our study has several limitations. First, we focused on general payments and did not include research payments, primarily because public concern about the effects of industry ties on patient care appears to be lower for research grants than for personal income.8 Because of this research payment exclusion, our estimates should be considered a lower bound for consumer exposure to physicians who accept industry payments. Second, we used a conservative and very high threshold (see online Appendix S1 for details) in determining whether the physicians that respondents named were indeed a match to the physicians reported in Open Payments. Because of this high threshold, some physicians who may have received payments were classified as not having received them, which may have led us to underestimate the prevalence of payments. Third, our estimates were based on our verified sample, the subgroup of respondents who named physicians whose identity we could verify based on the physician’s name and location. Individuals in our verified sample were similar along many dimensions to those whose named physicians could not be verified at our match threshold, although our verified sample does appear to be older, sicker, wealthier, and more likely to have health insurance (see online Appendix S1, Table A1, for a detailed comparison of these two groups). Finally, although our survey response rate was good relative to other consumer and web surveys, there may be nonresponse bias. In our nonresponse analysis (online Appendix S1, Table A2), we found that respondents were more likely to have health insurance than nonrespondents. Most other characteristics, including education and health status, were similar.

These findings provide a new, population-based view of the reach of the industry. Our estimates point to a far greater industry reach at the population level than physician-based estimates of industry contact have suggested. They also illuminate the prevalence of industry payments and awareness of industry-physician ties at the moment Open Payments became the national standard, providing a useful baseline by which to evaluate the law’s effects.

Our results raise important questions about what policymakers can do to improve patients’ awareness of industry payment information. Perhaps CMS, which also collects other information on providers, could establish a one-stop shop website where patients could view industry payments along with other information about their providers. It could require physicians to notify patients about this website, as they do with privacy provisions of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act. Payers, who also benefit from their patients being more knowledgeable about their doctors, could include industry payment information in the descriptive information they provide online about physicians in their network. Given patients’ stated interest in this kind of information,8 it seems important to preserve transparency initiatives like Open Payments even if other aspects of the Affordable Care Act are repealed.

The extent to which and the way in which patients and providers use this information should also be investigated more thoroughly. Some patients will want to initiate conversations with their doctors, whereas others may view industry ties as unimportant relative to other considerations. In other areas of health care quality, such as cardiac surgery outcomes reporting, transparency initiatives appear to have had little effect on consumer decisions, yet have had interesting effects on providers.27 , 28 How Open Payments implementation will unfold remains to be seen, but it will—and should—be closely watched.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

(PDF 132 kb)

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the Greenwall Foundation for its financial support of this project. The sponsor played no role in the design or conduct of the study or the interpretation of results. Drs. Campbell, Carpenter, and Lehmann were supported in part by the Edmond J. Safra Foundation through the Harvard University Edmond J. Safra Center for Ethics. We thank Charles V. Gray, Alec McQuilkin, and Melanie Mason for research assistance, Wayne Appleton for technical support, Mary Baitinger for administrative assistance, and Wendy Mansfield and Sergei Rodkin at GfK for coordinating the administration of the survey.

Disclosure

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not represent the official views of the Veterans Health Administration, the National Center for Ethics in Health Care, or the U.S. government.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Genevieve Pham-Kanter, Phone: 267.359.6163, Email: gpkanter@drexel.edu.

Michelle M. Mello, Phone: 650.725.3894, Email: mmello@law.stanford.edu.

Lisa Soleymani Lehmann, Phone: 202.632.8457, Email: lisa.lehmann@va.gov.

Eric G. Campbell, Phone: 617.726.5213, Email: ecampbell@partners.org.

Daniel Carpenter, Phone: 617.495.8280, Email: dcarpenter@gov.harvard.edu.

References

- 1.Section 6002 of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. Public Law 111–148. http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/PLAW-111publ148/pdf/PLAW-111publ148.pdf. Accessed 26 Jan 2017.

- 2.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. 42 CFR Parts 402 and 403. Medicare, Medicaid, Children’s Health Insurance Programs; transparency reports and reporting of physician ownership or investment interests. Federal Register 78. 2013. https://www.cms.gov/OpenPayments/Downloads/Affordable-Care-Act-Section-6002-Final-Rule.pdf. Accessed 26 Jan 2017. [PubMed]

- 3.Official website for Open Payments. https://www.cms.gov/OpenPayments/index.html. Accessed 26 Jan 2017.

- 4.US Senate Special Committee on Aging. Grassley, Kohl say public should know when pharmaceutical makers give money to doctors. Press release. September 7, 2007. http://www.aging.senate.gov/press-releases/grassley-kohl-say-public-should-know-when-pharmaceutical-makers-give-money-to-doctors. Accessed 26 Jan 2017.

- 5.Chimonas S, Rozario NM, Rothman DJ. Show us the money: lessons in transparency from state pharmaceutical marketing disclosure laws. Health Serv Res. 2010;45:98–114. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2009.01048.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hampson LA, Agrawal M, Joffe S, Gross CP, Verter J, Emanuel EJ. Patients’ views on financial conflicts of interest in cancer research trials. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2330–2337. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa064160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hwong AR, Qaragholi N, Carpenter D, Joffe S, Campbell EG, Lehmann LS. A systematic review of state and manufacturer physician payment disclosure websites: implications for implementation of the Sunshine Act. J Law Med Ethics. 2014;42:208–219. doi: 10.1111/jlme.12136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Licurse A, Barber E, Joffe S, Gross C. The impact of disclosing financial ties in research and clinical care: a systematic review. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:675–682. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lo B, Field MJ, editors. Conflict of interest in medical research, education, and practice. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rosenbaum L. Understanding bias - the case for careful study. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1959–1963. doi: 10.1056/NEJMms1502497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rosenthal MB, Mello MM. Sunlight as disinfectant - new rules on disclosure of industry payments to physicians. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:2052–2054. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1305090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Santhakumar S, Adashi EY. The Physician Payment Sunshine Act: testing the value of transparency. JAMA. 2015;313:23–24. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.15472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Steinbrook R. Online disclosure of physician-industry relationships. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:325–327. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0810197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weinfurt KP, Friedman JY, Allbrook JS, Dinan MA, Hall MA, Sugarman J. Views of potential research participants on financial conflicts of interest. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:906–906. doi: 10.1007/BF02743135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pham-Kanter G. Act II of the Sunshine Act. PLoS Med. 2014; e1001754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Campbell EC, Gruen RL, Moutford J, et al. A national survey of physician-Industry relationships. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1742–50. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa064508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fleischman W, Ross JS, Melnick ER, Newman DH, Venkatesh AK. Financial ties between emergency physicians and industry: insights from Open Payments data. Ann Emerg Med. 2016;68:153–158.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2016.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Iyer S, Derman P, Sandhu HS. Orthopaedics and the Physician Payments Sunshine Act. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2016;98:e18. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.O.00343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kesselheim AS, Robertson CT, Siri K, Batra P, Franklin JM. Distributions of industry payments to Massachusetts physicians. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:2049–2052. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1302723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marshall DC, Jackson ME, Hattangadi-Gluth JA. Disclosure of industry payments to physicians: an epidemiologic analysis of early data from the Open Payments program. Mayo Clin Proc. 2016;91:84–96. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2015.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Parikh K, Fleischman W, Agrawal S. Industry relationships with pediatricians: findings from the Open Payments Sunshine Act. Pediatrics. 2016;137:320154440. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-4440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rathi VK, Samuel AM, Mehra S. Industry ties in otolaryngology: initial insights from the Physician Payment Sunshine Act. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2015;152:993–999. doi: 10.1177/0194599815573718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pew Research Center. Assessing the representativeness of public opinion surveys. 2012. http://www.people-press.org/2012/5/15/assessing-the-representativeness-of-public-opinion-surveys. Accessed 26 Jan 2017.

- 24.Manfreda KL, Bosnjak M, Berzelak J, Haas I, Vehovar V. Web surveys versus other survey modes: a meta-analysis comparing response rates. Int J Mark Res. 2008;50:79–104. [Google Scholar]

- 25.National Research Council. Nonresponse in social science surveys: a research agenda. Tourangeau R, Plewes TJ, eds. Panel on a research agenda for the future of social science data collection, Committee on National Statistics, Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education, National Research Council. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2013.

- 26.Sismondo S. Key opinion leaders and the corruption of medical knowledge: what the Sunshine Act will and won’t cast light on. J Law Med Ethics. 2013;41(3):635–43. doi: 10.1111/jlme.12073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schneider EC, Epstein AM. Use of public performance reports: a survey of patients undergoing cardiac surgery. JAMA. 1998;279(20):1638–1642. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.20.1638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hannan EL, Sarrazin MS, Doran DR, Rosenthal GE. Provider profiling and quality improvement efforts in coronary artery bypass graft surgery: the effect on short-term mortality among Medicare beneficiaries. Med Care. 2003;41(10):1164–1172. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000088452.82637.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(PDF 132 kb)