Abstract

Management of type 1 diabetes in patients who have insulin hypersensitivity is a clinical challenge and places patients at risk for recurrent diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA). Hypersensitivity reactions can be due to the patient’s response to the insulin molecule itself or one of the injection’s non-insulin components. It is therefore crucial for clinicians to quickly recognize the type of hypersensitivity reaction that is occurring and identify potentially immunogenic additives for the purpose of directing therapy as various insulin preparations have differing ingredients. We present the case of a 23-year-old diabetic female with common variable immunodeficiency (CVID) and autoimmune enteropathy who developed a type III hypersensitivity reaction to multiple formulations of subcutaneous insulin after years of use and the challenges of devising a long-term management strategy.

KEY WORDS: insulin hypersensitivity, type III hypersensitivity, insulin allergy

INTRODUCTION

Type 1 diabetes is a disease commonly managed by internists, the cornerstone of which is insulin therapy. Though relatively uncommon, hypersensitivity reactions to insulin make disease management significantly more challenging and place the patient at risk for diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA). As such, it is important for physicians to recognize insulin hypersensitivity early and respond accordingly. Reported cases of type III hypersensitivity reactions to insulin have generally been limited to particular formulations of insulin such as insulin detemir, insulin aspart, or NPH insulin,1 – 3 associated with a blood dyscrasia,4 or included an element of type I hypersensitivity.5 We describe the case of a type I diabetic with common variable immunodeficiency (CVID) and autoimmune enteropathy who presented to the hospital with DKA secondary to a type III hypersensitivity reaction to all available forms of subcutaneous insulin and share a successful management strategy.

CASE

A 23-year-old female with CVID, autoimmune enteropathy, and type 1 diabetes mellitus presented to the emergency department with malaise, blood glucose >500 mg/dl, ketonuria, and acidemia (pH 6.86) consistent with the diagnosis of diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA). The patient had gradually discontinued her lispro and glargine insulin injections over the 3 weeks preceding admission because of the development of painful skin lesions at her injection sites. The lesions began as a pruritic rash approximately 30 min after each insulin injection, became progressively swollen and painful over the course of 2 to 3 h, and then resolved on their own after several days. She tolerated insulin injections for several years and maintained her presenting regimen for more than 18 months. Notably, she also stopped taking her other long-standing medications (prednisone 5 mg daily, subcutaneous immunoglobulin 8 gm weekly, colchicine 0.6 mg daily, and mercaptopurine (6-MP) 50 mg daily) after her prescriptions ran out several months prior. Her hemoglobin A1c was found to be 12.1%, supporting a history of prolonged medication non-adherence and poor glucose control. Her cutaneous examination at presentation was significant for large, tender, indurated, purpuric plaques scattered on the lower abdomen and thighs, which she identified as sites of prior insulin injections (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Patient presented with tender, indurated, purpuric plaques scattered on the abdomen at sites of prior insulin injections

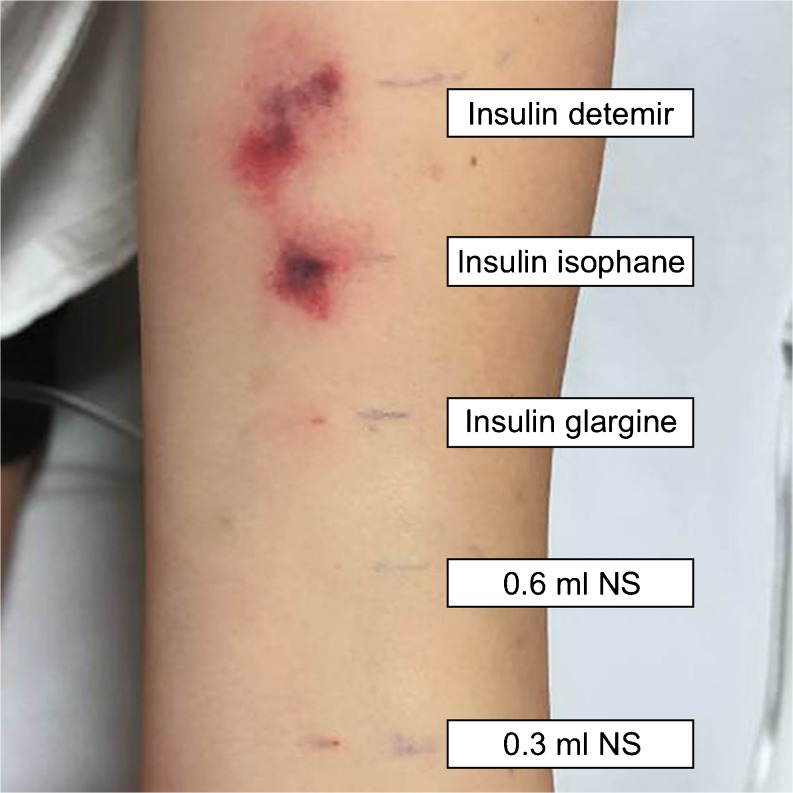

During her hospitalization, the patient’s blood glucose was adequately controlled with intravenous regular insulin; however, she remained unable to tolerate various subcutaneous insulin preparations (Table 1) because of the persistent development of painful skin lesions at the injection sites. Initial concern was for a local reaction to an excipient or additive in the available insulin preparations, but a review of these ingredients did not reveal a single unique compound able to explain the observed cutaneous response. Of note, the patient did tolerate subcutaneous saline injections, low-molecular-weight heparin (enoxaparin), and immunoglobulin without difficulty. A lesional skin biopsy was performed, and pathology demonstrated a neutrophilic infiltrate of the mid to deep dermal vessels with focal fibrinoid deposition and extravasated erythrocytes consistent with leukocytoclastic vasculitis (LCV) (Fig. 2).

Table 1.

Initial Intradermal Challenge

| Site no. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4* | 5* | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brand name | Humulin N® | Humulin R® | Novolog® | Levemir® | Lantus® | Apidra® |

| Generic name | Insulin isophane | Regular insulin | Insulin aspart | Insulin detemir | Insulin glargine | Insulin glulisine |

*Most intense reactions

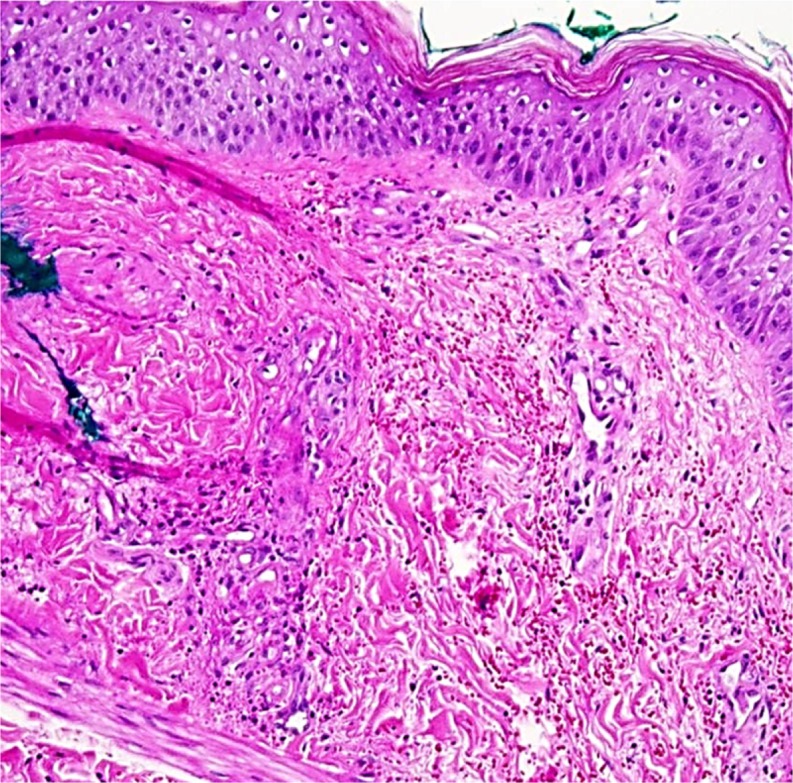

Figure 2.

Lesional skin biopsy demonstrates neutrophilic infiltrate, fibrinoid deposition and extravasated erythrocytes consistent with leukocytoclastic vasculitis (LCV)

Further injectable insulin trials were performed in an attempt to find a tolerable regimen in the short term. Initially, low doses of regular insulin mixed with methylprednisolone (0.4 mg methylprednisolone per 1 unit insulin) lessened the reaction. However, this combination failed with modestly higher insulin doses, and there was concern that subcutaneous methylprednisolone would lead to lipoatrophy over time. The patient next tried a slow infusion insulin pump. Insulin glulisine (Apidra®) was selected because it does not contain zinc, a potentially immunogenic additive. The pump was started at a very slow rate of 0.025 units per hour. The insulin was initially well tolerated, but a skin reaction again developed when the insulin infusion rate reached 0.800 units per hour on day 7 of the trial.

At this point, the Allergy and Immunology service recommended she restart her maintenance immune suppression with 6-MP 50 mg daily—which she had previously taken to control autoimmune enteropathy—as corticosteroids are not an appropriate long-term treatment for cutaneous leukocytoclastic vasculitis. After 1 week of 6-MP therapy, a re-challenge with slow-infusion insulin glulisine was again unsuccessful. It was thought that the 6-MP had not yet reached its maximal effect, and to act as a bridge the patient was further immunosuppressed with IV methylprednisolone 60 mg every 6 h for 3 days. Subsequently, the patient tolerated a single 3-unit injection of insulin glulisine, but developed localized symptoms several hours after resuming the insulin pump at a rate of 1 unit per hour, suggesting a dose-dependent reaction. She was then transitioned to oral prednisone 40 mg daily and restarted on colchicine at 0.3 mg twice daily in addition to the 50 mg 6-MP.

At this juncture, a multidisciplinary meeting with internal medicine, endocrinology, allergy and immunology, and dermatology was held. The decision was made to repeat intradermal testing of several basal insulins, as the patient had recently been able to tolerate low-doses of short-acting insulin glulisine (Table 2). Her regimen of immunosuppressive medications was to be continued without prednisone, because glucocorticoid therapy did not appear to provide benefit outweighing its potential harms. Subsequently, the patient tolerated low-dose insulin glargine (Lantus®) without any reaction (Fig. 3). Insulin glargine injections were then titrated over 3 days, and the patient was eventually able to discontinue IV regular insulin. She was discharged after a 44-day hospital stay on insulin glulisine 9 units three times a day before meals and insulin glargine 8 units every 12 h, along with her former regimen of 50 mg 6-MP and 0.6 mg colchicine daily.

Table 2.

Intradermal Re-challenge

| Site no. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brand name | --- | --- | Lantus® | Humulin N® | Levemir® |

| Manufacturer | Hospira | Hospira | Sanofi-Aventis | Eli Lilly and Company | Novo Nordisk |

| Generic name | Normal saline (0.9% NaCl) |

Normal saline (0.9% NaCl) |

Insulin glargine (100 units) |

Insulin isophane (100 units) |

Insulin detemir |

| Inactive ingredients* | --- | --- | Zinc (30 mcg) Meta-cresol (2.7 mg) Glycerol 85% (20 mg) Polysorbate (20 mcg) HCl/NaOH (pH = 4)† Water for injection |

Protamine sulfate (0.35 mg) Glycerin (16 mg) Dibasic sodium phosphate (3.78 mg) Meta-cresol (1.6 mg) Phenol (0.65 mg) Zinc oxide (0.025 mg) HCl/NaOH (pH = 7-7.5)† Water for injection |

Zinc (65.4 mcg) Meta-cresol (2.06 mg) Mannitol (30.0 mg) Phenol (1.80 mg) Disodium phosphate dehydrate (0.89 mg) NaCl (1.17 mg) HCl/NaOH (pH = 7.4)† Water for injection |

| Volume | 0.03 ml | 0.06 ml | 0.03 ml (3 units) | 0.03 ml (3 units) | 0.03 ml (3 units) |

| Response (mm) | 0 × 0 | 0 × 0 | 3 × 5, no flare | 5 × 5, no flare | 10 × 8 with a 20 × 20 flare |

*All amounts of ingredients are based on the amount per 1 ml

†Hydrochloric acid and sodium hydroxide are used to target pH

Figure 3.

Results of repeat intradermal testing of basal insulins after 24 h

Six months after admission, she was adherent to her medications but continued to experience mild reactions in a dose-dependent manner to some of her injections. Her hemoglobin A1c improved significantly to 7.7% and she began to explore the possibility of a pancreatic transplant.

DISCUSSION

Hypersensitivity reactions to insulin have been described since its discovery in 1922. Prior to the development and approval of human insulin in the early 1980s, only animal insulin (bovine and porcine) was available. Studies from the 1950s–1960s reported hypersensitivity reactions to purified animal insulin occurred in as many as 50–60% of patients.6 , 7 Current estimates suggest the incidence of insulin hypersensitivity reactions to presently available recombinant and analog insulins to be quite low at 0.1–3% of patients.8

Insulin “allergy” is often used interchangeably to describe both type I and type III hypersensitivity reactions, although this phrasing is only correct in reference to type I. Type I hypersensitivity is the most commonly described reaction to human insulin preparations and is mediated by IgE.9 Repeated exposure to the antigen leads to the release of vasoactive substances such as histamine and leukotrienes from sensitized mast cells and basophils. Symptoms characteristically develop rapidly following the administration of insulin and can include localized erythema and swelling or more generalized pruritus, angioedema, and urticaria.10 There have also been reports of a biphasic IgE-mediated reaction that involves pruritus and swelling within 15 min of injection, followed by a second, more intense reaction 2 to 6 h after the initial injection.11 If an alternative insulin preparation does not exist, or if the hypersensitivity is to insulin itself, desensitization may be considered with either diluted subcutaneous insulin injections12 or by continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion (CSII) via an insulin pump.13 Topical or systemic glucocorticoid therapy may also be considered in the treatment of type I hypersensitivity reactions, as appropriate.14 Several of these approaches were attempted unsuccessfully in our patient, and in retrospect this was to be expected given that she did not have evidence of a type I hypersensitivity reaction.

Type III hypersensitivity reactions, as experienced in our patient, are much less common. These reactions involve deposition of antigen-antibody complexes in vessels or tissues, leading to the recruitment of neutrophils and complement activation. Unlike type I reactions, type III present in a delayed manner—typically 2 to 6 h after insulin injection—with predominately localized symptoms.9 If avoidance of insulin is not an option and an alternative non-reactive formulation cannot be identified, therapy should be directed at immunosuppression. While previous cases have found insulin-induced LCV to be responsive to systemic glucocorticoids,3 , 5 these medications are best used to transition to other immunosuppressants because of their long-term side effects. In our particular case, it took several weeks of immunosuppression with 6-MP and colchicine before our patient was able to tolerate any insulin preparation. Similar success at treating insulin-induced LCV had previously been found using azathioprine and methotrexate.4

Regardless of the type of hypersensitivity, it is important to note that reactions to insulin injections may not be directed at the insulin itself. Many of the excipients and/or preservatives in insulin can induce similar hypersensitivity responses, including meta-cresol, protamine, zinc, etc. In addition, such additives can lead to localized delayed type hypersensitivity reactions (type IV) as well.9 , 15 It is therefore crucial to proper management to distinguish between patients who are reacting to the insulin molecule itself and those who are reacting to one of the injection’s non-insulin components. Patients who are unable to tolerate specific excipients may be successfully managed on alternative insulin preparations without requiring immunosuppression.

The clinical and histological findings on skin examination can be helpful in distinguishing between type I and type III hypersensitivity reactions. With our patient, the development of urticaria or pruritus within minutes to hours after administering subcutaneous insulin initially raised concern for type I hypersensitivity; however, she lacked the systemic symptoms more typical of a type I reaction. Biopsy of a representative lesion revealed LCV, which is more consistent with IgG and neutrophil-mediated, localized, type III hypersensitivity. LCV arises via deposition of circulating immune complexes in the walls of cutaneous small vessels. Although not necessary in our case, the use of direct immunofluorescence can be helpful in identifying these complexes.3

Alternate therapeutic options to immunosuppression for insulin-dependent diabetics with insulin hypersensitivity are quite limited. Pancreas transplantation would theoretically eliminate the need for subcutaneous insulin; however, this entails significant surgical risks and long-term immunosuppression that must be considered.16 , 17 Intraperitoneal administration of insulin via continuous intraperitoneal insulin infusion (CIPII) with an implantable insulin pump has been studied to improve glycemic control in patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus for whom other therapies have failed, although this treatment is neither cost effective nor widely available.18 Lastly, inhaled insulin would appear to be an attractive option for patients with cutaneous hypersensitivity reactions to insulin, although to our knowledge no data exist evaluating its use in such patients, and it can currently be found only as a short-acting formulation.19

This case demonstrates the challenge of treating a type 1 diabetic who has developed a type III hypersensitivity response to all available forms of insulin. Initial efforts to identify a tolerable insulin preparation and to slowly wean the patient back onto her previous insulin regimen were meant to avoid long-term immunosuppressive medications, but ultimately proved inadequate. Our patient had been treated with immunomodulating agents prior to her development of type 1 diabetes because of her history of autoimmune enteropathy. It is possible these agents (6-MP and colchicine) had prevented a hypersensitivity reaction to insulin from occurring earlier and their discontinuation was what led to her hospitalization. More rapid recognition of the potential significance of her immunosuppressive medications and their immediate re-initiation would have likely shortened her hospital admission. Although not typically used to treat insulin hypersensitivity, these immunomodulating agents may have benefit for future patients who develop refractory cases. This unusual combination of medications also speaks to the importance of coordinating with Endocrinology and Allergy and Immunology when insulin hypersensitivity is on the differential diagnosis.

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to Dr. Kenneth Ellington, who is affiliated with the Department of Pathology at Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC. He made a substantial contribution to the selection and interpretation of the histopathologic images in this report. Dr. Agboola is supported by grant T32-AI007062.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Darmon P, Castera V, Koeppel MC, Petitjean C, Dutour A. Type III allergy to insulin detemir. Diabetes Care. 2005;28(12):2980. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.12.2980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marusic S, Vlahovic-Palcevski V, Ljubanovic D. Leukocytoclastic vasculitis associated with insulin aspart in a patient with type 2 diabetes. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2009;47(10):603–605. doi: 10.5414/CPP47603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rachid B, Rabelo-Santos M, Mansour E, de Lima Zollner R, Velloso LA. Type III hypersensitivity to insulin leading to leukocytoclastic vasculitis. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2010;89(3):e39–40. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Mandrup-Poulsen T, Mølvig J, Pildal J, et al. Leukocytoclastic vasculitis induced by subcutaneous injection of human insulin in a patient with type I diabetes and essential thrombocytemia. Diabetes Care. 2002;25(1):242–243. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Silva ME, Mendes MJ, Ursich MJ, et al. Human insulin allergy-immediate and late type III reactions in a long-standing IDDM patient. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 1997;36(2):67–70. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Paley R, Tunbridge R. Dermal reactions to insulin therapy. Diabetes. 1952;1(1):22–27. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Arkins JA, Engbring NH, Lennon EJ. The incidence of skin reactivity to insulin in diabetic patients. J Allergy. 1962;33:69–72. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Radermecker RP, Scheen AJ. Allergy reactions to insulin: effects of continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion and insulin analogues. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2007;23(5):348–355. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Ghazavi MK, Johnston GA. Insulin allergy. Clin Dermatol. 2011;29(3):300–305. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Mattson JR, Patterson R, Roberts M. Insulin therapy in patients with systemic insulin allergy. Arch Intern Med. 1975;135(6):818–821. [PubMed]

- 11.deShazo RD, Boehm TM, Kumar D, et al. Dermal hypersensitivity reactions to insulin: correlations of three patterns to their histopathology. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1982;69(2):229–237. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Pratt EJ, Miles P, Kerr D. Localized insulin allergy treated with continuous subcutaneous insulin. Diabet Med. 2001;18(6):515–516. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Moyes V, Driver R, Croom A, Mirakian R, Chowdhury TA. Insulin allergy in a patient with type 2 diabetes successfully treated with subcutaneous insulin infusion. Diabet Med. 2006;23(2):204–206. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Grant W, deShazo RD, Frentz J. Use of low-dose continuous corticosteroid infusion to facilitate insulin pump use in local insulin hypersensitivity. Diabetes Care. 1986;9(3):318–319. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Schernthaner G. Immunogenicity and allergenic potential of animal and human insulins. Diabetes Care. 1993;16(Suppl 3):155–165. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Léonet J, Malaise J, Goffin E, et al. Solitary pancreas transplantation for life-threatening allergy to human insulin. Transpl Int. 2006;19(6):474–477. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Léonet J, Malaise J, Squifflet JP. Refractory insulin allergy: pancreas transplantation or immunosuppressive therapy alone? Transpl Int. 2010;23(7):e39–40. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Logtenberg SJ, Kleefstra N, Houweling ST, et al. Improved glycemic control with intraperitoneal versus subcutaneous insulin in type 1 diabetes: a randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(8):1372–1377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Cahn A, Miccoli R, Dardano A, Del Prato S. New forms of insulin and insulin therapies for the treatment of type 2 diabetes. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2015;3(8):638–652. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(15)00097-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]