Abstract

Human aging is a lifelong process characterized by a continuous trade-off between pro-and anti-inflammatory responses, where the best-adapted and/or remodeled genetic/epigenetic profile may develop a longevity phenotype. Centenarians and their offspring represent such a phenotype and their comparison to patients with age-related diseases (ARDs) is expected to maximize the chance to unravel the genetic makeup that better associates with healthy aging trajectories. Seemingly, such comparison is expected to allow the discovery of new biomarkers of longevity together with risk factor for the most common ARDs. MicroRNAs (miRNAs) and their shuttles (extracellular vesicles in particular) are currently conceived as those endowed with the strongest ability to provide information about the trajectories of healthy and unhealthy aging. We review the available data on miRNAs in aging and underpin the evidence suggesting that circulating miRNAs (and cognate shuttles), especially those involved in the regulation of inflammation (inflamma-miRs) may constitute biomarkers capable of reliably depicting healthy and unhealthy aging trajectories.

Keywords: Centenarians, Offspring of centenarians, Circulating microRNAs, Aging trajectories, miR-21-5p

1. Introduction

Human aging is a lifelong process that likely begins in utero (Menon, 2016) and is characterized by a dynamic phenotype that changes over time. Continuous interactions among genetic and epigenetic makeup and environmental (e.g. microbiota, lifestyle and diet) and stochastic factors influence the possibility to reach the limit of the human lifespan. The main feature of the aging process is a chronic, progressive proinflammatory status that has been named “inflammaging” (Franceschi et al., 2000, 2007; Cevenini et al., 2013; Salvioli et al., 2013), and it is currently considered as a major risk factor for the most common age-related diseases (ARDs) (Xia et al., 2016). Aging involves the entire organism; however, not all cell types, tissues, organs, and systems age at the same rate (Cevenini et al., 2008). Indeed, it is conceivable that different cells types are characterized by different rates of aging, and that senescent cells may contribute to spread senescence to younger cells (Olivieri et al., 2015a). The build-up of senescent cells during aging sustains and propagates inflammaging. A variety of different conditions can contribute to the systemic spread of inflammaging: i) the release of a number of soluble factors from senescent cells that have acquired a senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP); ii) the release of apoptotic/necrotic cell-derived molecules (Danger Associated Molecular Patterns, DAMPs) induced by age-damage-related modifications (Franceschi and Campisi, 2014); and iii) the release of proinflammatory factors from cells infected by pathogens e.g. viruses, (Long et al., 2016). Very recent data also suggest an effect due to inflammatory molecules, such as IL-6, on tissue remodeling and cell reprogramming emerging from cell senescence process in in vivo models (Mosteiro et al., 2016).

Inflammation related molecules seem to be shuttled into blood or lymph by different nano/microvesicles and to be captured by immune system cells, thus contributing to immunosenescence (Su et al., 2013). On the other hand, preservation of healthy state during aging may be ensured by efficient enzymatic and cell repair systems, that counteract the changes induced by harmful, chronic interactions with external and internal exposomes, i.e. all the types of exposures which an individual encounter during the lifetime (Wild, 2005; Nakamura et al., 2014). It is thus conceivable that the trade-off between pro-and anti-inflammatory molecules stimulates organism adaptation, and that the best adapted and/or remodeled genetic/epigenetic profile leads to development of the longevity phenotype. In this regard, centenarians and, especially, supercentenarians, who have avoided or postponed most ARDs, provide the best example of adaptation/remodeling and represent the paradigm of successful aging (Franceschi et al., 1995).

We review the evidence suggesting that circulating molecules such as microRNAs (miRNAs, miRs), particularly those involved in the modulation of inflammation (inflamma-miRs), and their shuttles may also act as modulators of inflammaging. Studies of their expression and targets have the potential to supply critical information on the aging process and its propagation through cells, tissues, and organs (Franceschi et al., 2016). However, circulating miRNAs (c-miRs) and their shuttles may serve not only as markers/mediators of healthy and pathological conditions, but also as tools, that can help monitor the aging trajectory. Ideally, early detection of deviation from a healthy trajectory would enable adopting therapeutic interventions to counteract or delay the onset of ARDs such as type 2 diabetes (T2DM) and cardiovascular disease (CVD). Since c-miRs reflect an individual’s biological adaptation to environmental exposures, their determination allows evaluating the biological changes induced by lifestyle interventions such as exercise and dietary changes (Flowers et al., 2015).

2. Healthy and unhealthy aging trajectories

The debate on whether aging is or is not programmed (Kowald and Kirkwood, 2016) appears to have been overtaken by the “quasi-programmed” theory (Blagosklonny, 2013), which is based on the main feature of aging, i.e. the close relationship between organism development and the deregulation of molecular pathways. Accordingly, over-activation of signal transduction pathways such as MTOR and exacerbation of normal cellular functions leading to alteration of homeostasis, malfunction, disease, and organ damage are likely the driving forces of aging processes.

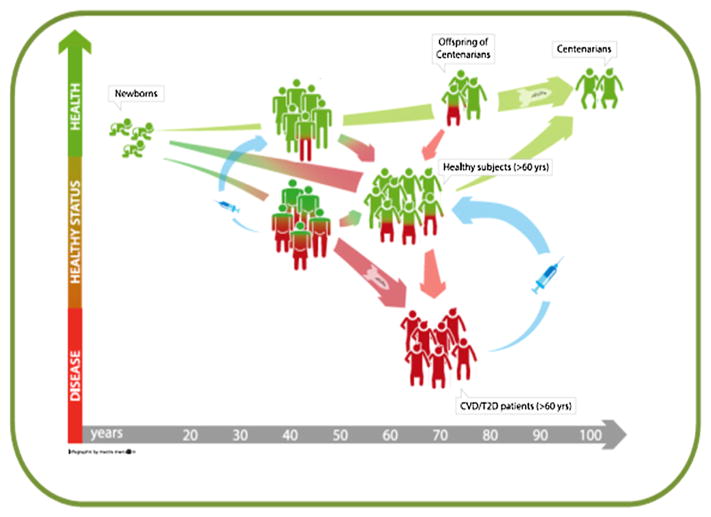

A way to characterize aging-related biomarkers would be the use of longitudinal studies from birth to the extreme limit of human lifespan, i.e. centenarians and supercentenarians (Fig. 1). Since this happens an almost unfeasible approach, the best alternative one is to examine healthy individuals of different ages, in a cross-sectional design. Given that, age-related functional decline is associated with an increased vulnerability to a variety of degenerative and chronic diseases, thus aging may be depicted as dichotomized into two divergent, healthy and unhealthy, trajectories (Fig. 1). Healthy elderly people (60–80 year olds) are not easily recruited because this age group is highly heterogeneous for the likelihood to achieve extreme old age. Moreover, pre-frail and ostensibly healthy elderly subjects may not exhibit ARD traits at the time of observation, but may develop ARDs soon after recruitment, and, finally, only a small proportion of such population will become centenarian. The health status of elderly people can be viewed as a track that eventually veers to a poorer health trajectory. Based on these premises, any sample of healthy subjects aged more than 60 years will necessarily include individuals who will eventually develop ARDs, and whose biomarkers will deviate away from a healthy trajectory. The deviation will be represented by the number of apparently “healthy” subjects, who do go on to develop disease (depicted in Fig. 1 as red and green people, respectively).

Fig. 1.

Trend of a hypothetical biomarker of aging: the deviation from a healthy (green) to a non-healthy (red) aging trajectory could be reversed by early disease prediction and personalized treatment (blue arrows). At present, the deviation toward T2DM and CVD cannot be reversed in late disease stages, but it is conceivable that in the future these patients could be recovered to a healthy trajectory. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

In this context, comparing elderly unhealthy people to extreme phenotypes (healthy centenarians and their offsprings) is expected to maximize the chance to find out any difference in the genetic/epigenetic make up. According to this tenet, this approach has been successfully undertaken to identify T2DM genetic risk variants (Garagnani et al., 2013). In fact, centenarians are characterized by well-preserved glucose metabolism and their offspring are endued with a better functional status, a lower risk of developing ARDs, and a reduced use of medications than the offspring of non-long-lived parents (Gueresi et al., 2013). Notably, the risk of mortality from CVD of centenarians’ offspring is 30% lower than in aged-matched people from the general population (Terry et al., 2004; Westendorp et al., 2009).

The view that the unhealthy aging trajectory can be traced by investigating patients with the most common ARDs is supported by the consideration that aging is the single largest risk factor for ARD development, and that studies of animal models have identified conserved pathways that modulate both the aging rate and ARD onset (Johnson et al., 2015).

In western countries, the most common ARDs are CVD, T2DM, cancer, and neurodegenerative diseases. The prevalence of diabetes is increasing at all ages, mostly due to rising overweight and obesity rates. T2DM patients experience early aging (Spazzafumo et al., 2013) and have distinctive genetic characteristics (Garagnani et al., 2013). Notably, 50% of T2DM patients die from CVD (primarily acute myocardial infarction and stroke), and their overall mortality risk is at least twice that of their peers without diabetes (Viña et al., 2013). On the other hand, the main predictors of mortality after acute myocardial infarction are diabetes and age (Wagner et al., 2014).

A sound approach to the study of aging is to establish at which point the aging trajectory begins to diverge and to identify the non-modifiable and modifiable factors that may defer it. If the genetic background is a non-modifiable risk factor for ARD development, epigenetic factors such as DNA/histone methylation and circulating non-coding RNA are emerging as functional biomarkers that can help monitor an individual’s aging trajectory (Bacalini et al., 2016; Wagner et al., 2016). Such epigenetic markers are the main mediators between genetic make-up and environmental factors (e.g. dietary restriction, exercise) influencing genomic stability and expression.

Complex trajectories involving a number of parameters, such as U–shaped trajectories, have been described where the combined effect of age, genetic profile, and diet/nutrients have been seen to have a role in determining the overall health status of elderly subjects (Jack et al., 2012). Nevertheless, limited data are available on the age-related trajectories of circulating miRs in healthy subjects including the oldest old, as summarized in Table 1a and as described in the next paragraph.

Table 1.

a. Circulating miRs in centenarians. b. Circulating miRs in human aging.

| Reference (a) | Biological sample | Profiling methods and donors | Validation methods and donors | miRs | Changes in centenarians | Additional data |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ElSharawy et al. (2012) | whole blood | Method: Geniom Biochip miRNA, with quantile normalization Donors: 15 centenarians/nonagenarians (96.4y) and 55 young (45.9y) |

Method: RT-qPCR: technical validation and validation on independent samples, normalized to RNU6B Donors: 15 centenarians/nonagenarians and 14–17–18 young controls |

miR-106a | down | |

| miR-126 | vs young | |||||

| miR-20a | ||||||

| miR-144* | ||||||

| miR-18a | ||||||

| miR-320d | up | |||||

| miR-320b | vs young | |||||

| Gombar et al. (2012) | EBV transformed immortalized B-cells | Method: Illumina sequencing (GA1), normalized to the total reads in each sample Donors: Ashkenazi Jewish female, 3 centenarians and 3 old (63y) |

Method: RT-qPCR, normalized to U6 snRNA Donors: same subjects analyzed in the profiling |

miR-363* | up | miR-363* down-regulates during aging (three groups: 50–60, 70–80, 80–90 y) |

| miR-1974 | vs old | |||||

| miR-223* | ||||||

| miR-148a | ||||||

| miR-148a* | ||||||

| Olivieri et al. (2012) | plasma | Method: MicroRNA Array pool A (Applied Biosystems), data normalized using the median Donors: 3 centenarians, 4 old (80y) and 4 young (20y) |

Method: RT-qPCR, normalized to miR-17-5p, and absolute quantification, determined by diluting synthetic miR-21 Donors: 111 subjects (20–105y) |

miR-21 | down | |

| vs old (66–95y); | ||||||

| up | ||||||

| vs young ( < 65y) | ||||||

| Serna et al. (2012) | Mononuclear cells | Method: GeneChip Array (Affymetrix), normalized with RMA algorithm Donors: 20 centenarians, 16 old (80y), 14 young (30y) |

Method: RT-qPCR, normalized to RNU66 and RPLPO Donors: same subjects analyzed in the profiling |

miR-21 | up | miR-19b down-regulates in old (80 y) |

| miR-130a | vs old and young groups | |||||

| Reference (b) | Biological samples | Profiling methods and donors | Validation methods and donors | miRs | Changes with age | Additional data |

|

| ||||||

| Noren Hooten et al. (2010) | PBMCs | Method: miRnome Array (System Biosciences), normalized to U1 expression Donors: 2 young (30y) and 2 old (64y) | Method: RT-qPCR, normalized to the average of 3 stable miRs (miR-147, miR-574-3p, miR-1469) Donors: 14 young and 14 old |

miR-103 miR-107 | down | |

| miR-128 miR-130a | ||||||

| miR-155 miR-24 | ||||||

| mIR-221 miR-496 | ||||||

| miR-1538 | ||||||

| Noren Hooten et al. (2013) | serum | Method: Illumina small-RNA seq, analyzed with miRDeep software Donors: 11 young (30y) and 11 old (64y) |

Method: RT-qPCR, normalized to miR-191 Donors: 20 young and 20 old |

miR-151a-3p | down | |

| miR-181a-5p | ||||||

| miR-1248 | ||||||

| Meder et al. (2014) | blood | Method: Geniom Biochip miRNA, with quantile normalization Donors: 109 subjects (19–105y) Method: Illumina small-RNA seq (HiSeq 2000), analyzed with miRDeep softwar Donors: 58 subjects (44–75y) |

miR-1284 | up | positive correlation with age | |

| miR-93-3p | ||||||

| miR-1262 | ||||||

| miR-34a-5p | ||||||

| miR-145-5p | ||||||

| Olivieri et al. (2014a) | plasma | Method: RT-qPCR, normalized to cel-miR-39 Donors: 44 young (20–45y), 57 elderly (46–75y), 35 old (≥75y) |

miR-126-3p | up | ||

| Zhang et al. (2015) | serum | Method: Solexa sequencing, total copy number of each sample was normalized to 100,000 Donors: pool serum from four different ages groups (22y, 40y, 59y, 70y) |

Method: RT-qPCR, absolute quantification Donors: 31 subjects (22y), 31 subjects (40y), 30 subjects (59y), 31 subjects (70y) |

miR-92a | up | Only miR-29b and miR-92a were significantly different for all four aging groups |

| miR-222 | ||||||

| miR-375 | ||||||

| miR-29b | down | |||||

| miR-106b | ||||||

| miR-130b | ||||||

| miR-142-5p | ||||||

| miR-340 | ||||||

| Ameling et al. (2015) | plasma | Method: Exiqon Serum/Plasma Focus microRNA PCR Panel, normalized to the lower quartile per sample Donors: 372 donors (22–79y) |

miR-126-3p | up | Additional variables (gender, BMI) | |

| miR-21-5p | ||||||

| miR-30b-5p | ||||||

| miR-30c-5p | ||||||

| miR-142-3p | ||||||

| let-7a-5p | ||||||

| miR-93-5p | down | |||||

3. Circulating miRs as biomarkers of healthy and unhealthy aging trajectories

Even though extracellular nucleic acids were first described in the human bloodstream more than 50 years ago, they have only recently been recognized as significant agents in intercellular signaling rather than as mere ‘spill-over’ (Dhahbi, 2014; Vickers and Remaley, 2012). Circulating nucleic acids, in particular small RNAs such as miRs (17–25 nt long), provide additional inter-tissue and inter-organ communication besides the classic mechanisms (hormones, cytokines, growth factors). Recent evidence has confirmed that some features of aging reflect the profile of circulating miRs (Weilner et al., 2013; Olivieri et al., 2012, 2013; Serna et al., 2012; Ghai and Wang, 2016). By applying Principal Component Analysis to centenarians’ results (representing “extraordinary aging”), we have found that their miRNome is similar to that of young individuals and different from that of septuagenarians (“ordinary aging”) (Serna et al., 2012). This finding demonstrates that centenarians are indeed on a “healthy trajectory” that has led to their long and remarkably disease free life.

Tables 1a and b analyse the most relevant researches on human blood (whole blood, plasma, serum, peripheral mononuclear cells, and immortalized B cell lines) and the effect of healthy aging on miR expression levels. The increase of miR levels (up-regulation) with age appears to be the most relevant result, particularly evident in centenarians. Significantly, the biological samples of centenarians are characterized by a distinctive miR profile. The tables also show the normalization procedure adopted in each work and being different in all cases, any comparative conclusion about the quantity of expression is very difficult. Additional variables have been taken into account, such as biological sample, method and group age making more complex definitive conclusions. Nevertheless, our investigations showed that the levels of c-miRs-21-5p and 126-3p increase during aging (Olivieri et al., 2012; Olivieri et al., 2014a), findings recently confirmed by other researchers (Ameling et al., 2015), as shown in the tables.

Moreover, miR-126-3p, which is highly expressed in endothelial and hematopoietic progenitor cells, is reduced in diabetic patients suffering from the complications of diabetes (Olivieri et al., 2014a), highlighting the role of miR levels in distinguishing healthy from unhealthy status.

Furthermore, the c-miR-146a is an important regulator in the interplay among DNA damage response (DDR), cell senescence and inflammaging (Olivieri et al., 2015a). We have designated c-miRs-21-5p, −126a and −146a as inflamma-miRs (Olivieri et al., 2013) for their role in inflammaging, but many other c-miRs with a possible pro-inflammatory role have recently been identified (Noren Hooten et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2015; Ameling et al., 2015), as reported in Table 1(a and b).

The comparison of miR expression in serum from young (mean age 30 years) and older (mean age 64 years) individuals has demonstrated miR-151a-5p, miR-181a-5p and miR-1248 down-regulation in the latter subjects (Noren Hooten et al., 2013). Intriguingly, miR-1248 has been reported to regulate the expression of mRNAs involved in inflammatory pathways, and miR-181a has been found to correlate negatively with the pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-6 and TNFα, and positively with the anti-inflammatory cytokines TGFβ and IL-10. These data further document that the interaction among inflammatory and anti-inflammatory molecules can help understand lifelong remodeling and the attainment of longevity (Franceschi et al., 2007).

Very recently, a cross-sectional design in 50, 55 and 60 years old individuals with documented life span (from 58 to 92 years) were analyzed. They were divided into two groups. i.e. long and short –lived, and a lifespan signature of c-miRs was proposed (miR-211-5p, 374a-5p, 340-3p, 376c-3p, 5095, 1225-3p) (Smith-Vikos et al., 2016). This work highlights the possibility to trace healthy and unhealthy trajectories starting at a critical age when the evolution driving force is decreased and age-related diseases start to develop, and concomitantly gene expression regulation is less finely tuned. Importantly, these dichotomized lifespan trajectories and miRs expression have also been identified in animal models, such as C. Elegans (Pincus et al., 2011), thus suggesting similar aging mechanisms in phylogenetically distant organisms.

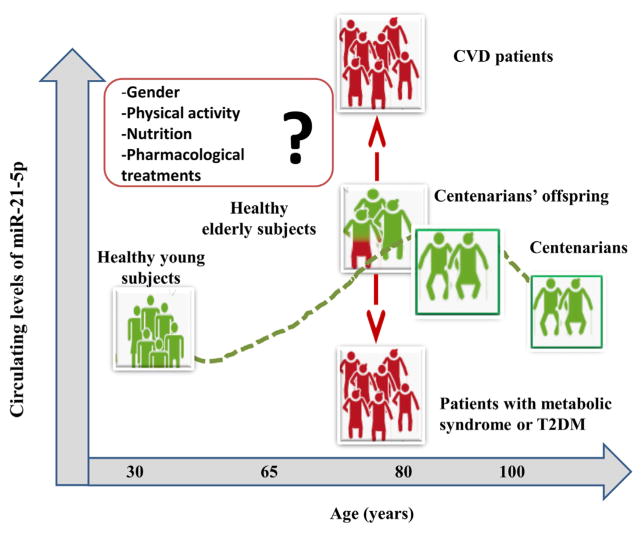

Patients with CVDs are unlikely to become centenarians, and their circulating miR patterns are believed to considerably differ from those of healthy subjects. Recently, a c-miR signature has been described in patients with acute heart failure (Ovchinnikova et al., 2016) and T2DM (Guay and Regazzi, 2013). However, among the c-miRs identified to date, miR-21-5p is the one that seems to characterize best the longevity phenotype, since it is under expressed in successful aging (Olivieri et al., 2012). In fact, we analyzed c-miR-21-5p levels in samples from healthy subjects with an age-range from 20 to more than 100 years old (Olivieri et al., 2012). This analysis allowed us to estimate the “physiological” modification of c-miR-21-5p associated with the “aging process”. Surprisingly, we observed a non-monotonic age-related trajectory characterized by an age-related increase until 80 years old, and by a slight decrease in subjects older than 80 years. Non monotonic changes similar to those observed for c-miR-21 were reported in different physiological parameters, such as blood glucose, diastolic blood pressure, serum cholesterol and body mass index (BMI) among others (Arbeev et al., 2011). Centenarians showed c-miR-21-5p levels lower than those of healthy subjects of 80 years old, suggesting that low levels of c-miR-21-5p are beneficial for longevity. This hypothesis was reinforced by results obtained in samples of patients affected by different ARDs, such as cancers and cardiovascular diseases (CVD). C-miR-21-5p levels were significantly increased in patients affected by acute myocardial infarction compared with age-matched healthy subjects (Zhang et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2014; Olivieri et al., 2014b). Significant increased levels of c-miR-21 have also been reported in patients affected by different types of cancers (Gao et al., 2016).

On the contrary, reduced levels of miR-21 in plasma and circulating cells were observed in patients affected by metabolic syndrome, T2DM and obesity (He et al., 2016; Zampetaki et al., 2010; Olivieri et al., 2015b; Mazloom et al., 2016). The reduced expression of miR-21 in circulating cells of obese subjects appears to be associated with an increased secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines, and likely, it suggests a similar role in centenarians, who are also characterized by anti-inflammatory balancing processes (Franceschi et al., 2007).

Overall, the concordance of the results obtained by a number of independent groups, confirms that c-miR-21-5p levels measured in patients affected by the most common ARDs are different from those observed in healthy subjects of the same age. Therefore c-miR-21-5p could be a promising candidate as biomarker of deviation from the healthy trajectory (as illustrated in Fig. 2), especially at old age, when the effects of adaptation and remodeling strongly interact with the selective effects due to mortality (Arbeev et al., 2016).

Fig. 2.

Trend of circulating miR-21-5p levels: the deviation from a healthy (green) to a non-healthy (red) condition can be monitored by circulating miR-21-5p levels. The figure presents circulating miR-21-5p levels in healthy subjects of different age and in groups of patients suffering from the most common age-related diseases (metabolic syndrome, T2DM, CVD). (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Since in the majority of the studies related to c-miR-21-5p levels were measured with relative expression method, that allows to obtain values expressed in arbitrary units, is quite difficult to identify an age-tailored threshold value to discriminate a “physiological aging” from a “pathological aging”. Further studies on largest samples of healthy subjects and with standardized methods for miR-21-5p detection, will allow to identify the age-tailored reference range of normal c-miR-21 levels.

Additionally, mounting evidence has been confirming that c-miR levels have the potential to monitor the efficacy of therapeutic interventions. Dynamic changes in their trends have suggested that some miRs are able to discriminate between the types of response to antitumor therapy (Ponomaryova et al., 2016; Chen et al., 2016) and postmenopausal estrogen-based hormone replacement therapy (Kangas et al., 2014).

It has recently been demonstrated that the levels of miR-140-5p and miR-650, which are markers for a wide range of human conditions, depend significantly on physical exercise training mode (Hecksteden et al., 2016). Therefore, if exercise is an important confounding factor for miR-based disease diagnosis, c-miRs modulated by training could prove useful to monitor rehabilitation compliance.

Altogether, a greater understanding of c-miR changes occurring during aging and of the conditions that affect them is needed before such novel markers can be applied in clinical practice.

4. Perspective contribution of circulating miR-extracellular vesicles to aging trajectories

Albeit conventional cell–cell communication modes depend mostly on extracellular ligand concentration and cell-surface receptor availability, the magnitude of circulating miR-mediated signaling responses relies on capture and uptake by target cells and their antigens/receptors. MiRs are functional after the uptake by target cells. These phenomena suggest that epigenetic modifications may be induced by a highly regulated compartment of circulating miRs (García-Olmo et al., 2010). Serum miRs are a pool of RNA molecules that are likely to be associated with different circulating carriers, such as exosomes and ectosomes (Cocucci and Meldolesi, 2015). Exosomes are small (30–120 nm in diameter), membrane vesicles that originate through the endocytic pathway, via the multivesicular bodies of the endosomal compartment (Simpson et al., 2008, 2009; Mathivanan et al., 2010). At variance, ectosomes are microvesicles that directly bud from the cellular plasma membrane and have an irregular shape and variable size (100–1000 μm). The study of exosomes and ectosomes, collectively called extracellular vesicles (EVs), has disclosed not only a different proteomic cargo, but also different biological characteristics (Choi et al., 2015). Besides their role in c-miR transport, they also carry a variety of bioactive molecules (e.g. cytokines, proteins, DNA) (Kim et al., 2013; Kahlert et al., 2014), thus providing an attractive research field for diagnostic and therapeutic applications (Thakur et al., 2014).

EVs act both on adjacent acceptor cells and on cells lying at considerably greater distance via the circulatory and lymphatic system. Such communication system provides control of cell development, cell fate, and tissue homeostasis, likely protecting the functional state of biological systems and affecting the chance of achieving longevity or developing ARDs. EVs may also mediate the extracellular spread of misfolded/pathogenic or garbage proteins in case of lysosome malfunction (Eitan et al., 2016) as well as viral or bacterial proteins and nucleic acids. EV-shuttled molecular communication undergoes major age-related modifications due to factors such as the increase of senescent cells within tissue and organs (Weilner et al., 2013). C-miRs can also be carried by protein complexes (containing Argonaute, or AGO1-2, proteins), nucleophosmin and lipoproteins (e.g. HDL) (Turchinovich et al., 2011; Turchinovich and Burwinkel, 2012; Wagner et al., 2013; Weilner et al., 2013). Even though some miR-protein associations may occur in a non-specific way (adsorption, entrapment), and some may reflect passive release from dead or damaged cells rather than active secretion, these data lead to hypothesize the existence of a multilevel system of communication and regulation.

In vitro studies have found that miRs released by senescent cells via EVs into the extracellular environment induce senescence in surrounding cells. In particular, cells expressing high miR-433 levels released it into growth media within EVs and induced cell senescence and chemoresistance in ovarian cancer cells (Weiner-Gorzel et al., 2015). Thus, miR-433 modulates the tumor microenvironment by inhibiting growth and inducing senescence in nearby cells. On the other hand, miRs released within EVs are also able to suppress senescence in recipient cells. For instance, miR-214, which controls endothelial cell function and angiogenesis, plays a dominant role in vesicle-mediated signaling between endothelial cells (Van Balkom et al., 2013); indeed, endothelial cell derived vesicles stimulated migration and angiogenesis in recipient cells, preventing senescence, whereas vesicles from miR-214-depleted endothelial cells failed to stimulate this process. According to a recent study (Weilner et al., 2016), EVs isolated from young donors enhance osteoblastogenesis in vitro compared with those from elderly subjects; in particular, reduced galectin-3 levels in the latter vesicles correlated with an altered osteoinduction potential.

In another study, miR microarray analysis of salivary exosomes from 15 young healthy individuals and 13 old subjects has identified miR-24-3p as a novel candidate biomarker of aging (Machida et al., 2015).

Since circulating EVs conceivably arise from all tissues and organs, they may provide a circulating representation of successful aging that may be difficult to obtain when the single tissue is examined. It can be expected that the assessment of their “normal levels” and the identification of the subpopulation(s) or EVs in the liquid biopsy will be relevant to provide reliable estimates of the miRs trajectories in healthy and unhealthy aging.

5. Challenges and perspectives

C-miRs have great potential as biomarkers in aging and ARD management. Moreover, miRs showing dysregulation in pathological conditions are emerging as novel tools that could be harnessed in therapeutic interventions against a broad array of cellular targets. Numerous preclinical and clinical trials are testing their effect on a variety of targets including cancer, CVD, and virus infection and proliferation. The challenges that need to be addressed before miRs can be used as biomarkers, and ultimately as therapeutic targets, must clearly be recognized. First and foremost, c-miR preparation and measurement should be standardized. Even though most studies have failed to consider the influence of factors like serum and plasma preparation, generalizing findings from patients of different age and sex and from different groups or labs (Sato et al., 2009) requires standardization of sample preparation. This is a precondition to reduce lab-to-lab variations and maximize the prospects for clinical use. Accurate determination of c-miR levels in a given cell type or body fluid is crucial to establish miRs as diagnostic biomarkers. Furthermore, standardization of data processing and analytical methods, including normalization, is critical to minimize technical variation and maximize the reliability of experimental outcomes (Meyer et al., 2010; Witwer, 2015).

6. Conclusions

Research of aging biomarkers and attempts to harness them to carry out personalized therapeutic interventions and monitor their efficacy are at the core of several European projects (Capri et al., 2015). At present, no biomarker alone can monitor healthy or unhealthy aging, even though recent data emphasize the value of molecular and DNA/RNA-based biomarkers. The study of c-miRs and their shuttles as biomarkers and functional modulators of aging-related pathways is generating interesting data. Among the panels of candidate miRs being proposed to assess the healthy aging trajectory, miR-21-5p appears to be one of the most powerful, given its different levels in subjects of different age with and without ARDs. Even though longitudinal cohort studies would clarify the significance of c-miR changes and better establish their predictive value, cross-sectional studies and maybe the combination of both experimental designs could be a suitable approach for miR-biomarker identification, as well as prognostic and diagnostic assessment, thus favoring translational medicine applications.

Altogether, current data suggest that different c-miRs have the ability to identify subjects experiencing healthy or unhealthy aging conditions, such as patients with CVD, T2DM, cancer, and neurodegenerative diseases. C-miRs may display non-monotonic, U–shaped trends suggesting that prediction of deviation from the healthy trajectory may be very complex. Future studies should elucidate how miRs can be better applied, not only as biomarkers of aging rate and disease, but also as predictive, diagnostic, and eventually therapeutic approaches for gene expression regulation. The ability to predict ARD onset using c-miRs, also in combination with other molecules, would be a great scientific achievement. Another critical objective is to harness the exosome transport system to the modulation of tissue-specific molecules and deliver therapeutic interventions, a goal that requires reliable identification of EV origin and a comprehensive understanding of organ cross-talk. Achievement of these objectives would involve a huge number of patients with a broad spectrum of diseases.

Acknowledgments

Funds were received from FARB2-2014-University of Bologna (project RFBO120790) to MC, from FP7 European Commission–grant agreement no. 602757 “HUMAN”-, and from Università Politecnica delle Marche, RSA 2015–2016 to FO.

We are grateful to Dr. Marzio Marcellini for his assistance with the preparation of Fig. 1. The authors are grateful to Word Designs for the language revision (www.silviamodena.com).

Abbreviations

- ARDs

age-related diseases

- CVD

cardiovascular disease

- EVs

extracellular vesicles

- miRs

microRNAs

- SASP

senescence-associated secretory phenotype

- T2DM

type 2 diabetes

References

- Ameling S, Kacprowski T, Chilukoti RK, Malsch C, Liebscher V, Suhre K, Pietzner M, Friedrich N, Homuth G, Hammer E, Völker U. Associations of circulating plasma microRNAs with age, body mass index and sex in a population-based study. BMC Med. Genomics. 2015;8:61. doi: 10.1186/s12920-015-0136-7. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s12920-015-0136-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arbeev KG, Ukraintseva SV, Akushevich I, Kulminski AM, Arbeeva LS, Akushevich L, Culminskaya IV, Yashin AI. Age trajectories of physiological indices in relation to healthy life course. Mech Ageing Dev. 2011;132(3):93–102. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2011.01.001. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.mad.2011.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arbeev KG, Cohen AA, Arbeeva LS, Milot E, Stallard E, Kulminski AM, Akushevich I, Ukraintseva SV, Christensen K, Yashin AI. Optimal versus realized trajectories of physiological dysregulation in aging and their relation to sex-specific mortality risk. Front Public Health. 2016;4:3. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2016.00003. http://dx.doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2016.00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bacalini MG, Deelen J, Pirazzini C, De Cecco M, Giuliani C, Lanzarini C, Ravaioli F, Marasco E, van Heemst D, Suchiman HE, Slieker R, Giampieri E, Recchioni R, Mercheselli F, Salvioli S, Vitale G, Olivieri F, Spijkerman AM, Dollé ME, Dollé ME, Sedivy JM, Castellani G, Franceschi C, Slagboom PE, Garagnani P. Systemic age-associated DNA hypermethylation of ELOVL2 gene: in vivo and in vitro evidences of a cell replication process. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2016 doi: 10.1093/gerona/glw185. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/gerona/glw185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Blagosklonny MV. Aging is not programmed: genetic pseudo-program is a shadow of developmental growth. ABBV Cell Cycle. 2013;12(24):3736–3742. doi: 10.4161/cc.27188. http://dx.doi.org/10.4161/cc.27188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capri M, Moreno-Villanueva M, Cevenini E, Pini E, Scurti M, Borelli V, Palmas MG, Zoli M, Schön C, Siepelmeyer A, Bernhardt J, Fiegl S, Zondag G, de Craen AJ, Hervonen A, Hurme M, Sikora E, Gonos ES, Voutetakis K, Toussaint O, Debacq-Chainiaux F, Grubeck-Loebenstein B, Bürkle A, Franceschi C. MARK-AGE population: from the human model to new insights. Mech Ageing Dev. 2015;151:13–17. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2015.03.010. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.mad.2015.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cevenini E, Invidia L, Lescai F, Salvioli S, Tieri P, Castellani G, Franceschi C. Human models of aging and longevity. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2008;8(9):1393–1405. doi: 10.1517/14712598.8.9.1393. http://dx.doi.org/10.1517/14712598.8.9.1393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cevenini E, Monti D, Franceschi C. Inflamm-ageing. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2013;16(1):14–20. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0b013e32835ada13. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/MCO.0b013e32835ada13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen SD, Sun XY, Niu W, Kong LM, He MJ, Fan HM, Li WS, Zhong AF, Zhang LY, Lu J. A preliminary analysis of microRNA-21 expression alteration after antipsychotic treatment in patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2016;244:324–332. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2016.04.087. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2016.04.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi DS, Kim DK, Kim YK, Gho YS. Proteomics of extracellular vesicles: exosomes and ectosomes. Mass Spectrom Rev. 2015;34(4):474–490. doi: 10.1002/mas.21420. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/mas.21420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cocucci E, Meldolesi J. Ectosomes and exosomes: shedding the confusion between extracellular vesicles. Trends Cell Biol. 2015;25(6):364–372. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2015.01.004. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tcb.2015.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhahbi JM. Circulating small noncoding RNAs as biomarkers of aging. Ageing Res Rev. 2014;17:86–98. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2014.02.005. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2014.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eitan E, Suire C, Zhang S, Mattson MP. Impact of lysosome status on extracellular vesicle content and release. Ageing Res Rev. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2016.05.001. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2016.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- ElSharawy A, Keller A, Flachsbart F, Wendschlag A, Jacobs G, Kefer N, Brefort T, Leidinger P, Backes C, Meese E, Schreiber S, Rosenstiel P, Franke A, Nebel A. Genome-wide miRNA signatures of human longevity. Aging Cell. 2012;11(4):607–616. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2012.00824.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1474-9726.2012.00824.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flowers E, Won GY, Fukuoka Y. MicroRNAs associated with exercise and diet: a systematic review. Physiol Genomics. 2015;47(1):1–11. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00095.2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.1152/physiolgenomics.00095.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franceschi C, Campisi J. Chronic inflammation (inflammaging) and its potential contribution to age-associated diseases. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2014;69(Suppl 1):S4–9. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glu057. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/gerona/glu057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franceschi C, Monti D, Sansoni P, Cossarizza A. The immunology of exceptional individuals: the lesson of centenarians. Immunol Today. 1995;16(1):12–16. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(95)80064-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franceschi C, Bonafè M, Valensin S, Olivieri F, De Luca M, Ottaviani E, De Benedictis G. Inflamm-aging an evolutionary perspective on immunosenescence. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2000;908:244–254. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb06651.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franceschi C, Capri M, Monti D, Giunta S, Olivieri F, Sevini F, Panourgia MP, Invidia L, Celani L, Scurti M, Cevenini E, Castellani GC, Salvioli S. Inflammaging and anti-inflammaging: a systemic perspective on aging and longevity emerged from studies in humans. Mech Ageing Dev. 2007;128(1):92–105. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2006.11.016. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.mad.2006.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franceschi C, Garagnani P, Vitali G, Capri M, Salvioli S. Inflammageing and garb-aging. Trends Endocrinol Metabol. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2016.09.005. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Y, Dai M, Liu H, He W1, Lin S, Yuan T, Chen H, Dai S. Diagnostic value of circulating miR-21: an update meta-analysis in various cancers and validation in endometrial cancer. Oncotarget. 2016 doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.12028. http://dx.doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.12028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Garagnani P, Giuliani C, Pirazzini C, Olivieri F, Bacalini MG, Ostan R, Mari D, Passarino G, Monti D, Bonfigli AR, Boemi M, Ceriello A, Genovese S, Sevini F, Luiselli D, Tieri P, Capri M, Salvioli S, Vijg J, Suh Y, Delledonne M, Testa R, Franceschi C. Centenarians as super-controls to assess the biological relevance of genetic risk factors for common age-related diseases: a proof of principle on type 2 diabetes. Aging (Albany NY) 2013;5(5):373–385. doi: 10.18632/aging.100562. http://dx.doi.org/10.18632/aging.100562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Olmo DC, Domínguez C, García-Arranz M, Anker P, Stroun M, García-Verdugo JM, García-Olmo D. Cell-free nucleic acids circulating in the plasma of colorectal cancer patients induce the oncogenic transformation of susceptible cultured cells. Cancer Res. 2010;70(2):560–567. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3513. http://dx.doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghai V, Wang K. Recent progress toward the use of circulating microRNAs as clinical biomarkers. Arch Toxicol. 2016 doi: 10.1007/s00204-016-1828-2. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00204-016-1828-2. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Gombar S, Jung HJ, Dong F, Calder B, Atzmon G, Barzilai N, Tian XL, Pothof J, Hoeijmakers JH, Campisi J, Vijg J, Suh Y. Comprehensive microRNA profiling in B-cells of human centenarians by massively parallel sequencing. BMC Genomics. 2012;13:353. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-13-353. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1471-2164-13-353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guay C, Regazzi R. Circulating microRNAs as novel biomarkers for diabetes mellitus. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2013;9:513–521. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2013.86. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nrendo.2013.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gueresi P, Miglio R, Monti D, Mari D, Sansoni P, Caruso C, Bonafede E, Bucci L, Cevenini E, Ostan R, Palmas MG, Pini E, Scurti M, Franceschi C. Does the longevity of one or both parents influence the health status of their offspring? Exp. Gerontol. 2013;48(4):395–400. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2013.02.004. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.exger.2013.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He QF, Wang LX, Zhong JM, Hu RY, Fang L, Wang H, Gong WW, Zhang J, Pan J, Yu M. Circulating microRNA-21 is downregulated in patients with metabolic syndrome. Biomed Environ Sci. 2016;29(5):385–389. doi: 10.3967/bes2016.050. http://dx.doi.org/10.3967/bes2016.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hecksteden A, Leidinger P, Backes C, Rheinheimer S, Pfeiffer M, Ferrauti A, Kellmann M, Sedaghat F, Meder B, Meese E, Meyer T, Keller A. miRNAs and sports: tracking training status and potentially confounding diagnoses. J Transl Med. 2016;14(1):219. doi: 10.1186/s12967-016-0974-x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s12967-016-0974-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jack CR, Jr, Vemuri P, Wiste HJ, Weigand SD, Lesnick TG, Lowe V, Kantarci K, Bernstein MA, Senjem ML, Gunter JL, Boeve BF, Trojanowski JQ, Shaw LM, Aisen PS, Weiner MW, Petersen RC, Knopman DS. Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. Shapes of the trajectories of 5 major biomarkers of Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2012;69(7):856–867. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2011.3405. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/archneurol.2011.3405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SC, Dong X, Vijg J, Suh Y. Genetic evidence for common pathways in human age-related diseases. Aging Cell. 2015;14(5):809–817. doi: 10.1111/acel.12362. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/acel.12362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahlert C, Melo SA, Protopopov A, Tang J, Seth S, Koch M, Zhang J, Weitz J, Chin L, Futreal A, Kalluri R. Identification of double-stranded genomic DNA spanning all chromosomes with mutated KRAS and p53 DNA in the serum exosomes of patients with pancreatic cancer. J Biol Chem. 2014;289(7):3869–3875. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C113.532267. http://dx.doi.org/10.1074/jbc.C113.532267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kangas R, Pöllänen E, Rippo MR, Lanzarini C, Prattichizzo F, Niskala P, Jylhävä J, Sipilä S, Kaprio J, Procopio AD, Capri M, Franceschi C, Olivieri F, Kovanen V. Circulating miR-21, miR-146a and Fas ligand respond to postmenopausal estrogen-based hormone replacement therapy–a study with monozygotic twin pairs. Mech Ageing Dev. 2014;143–144:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2014.11.001. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.mad.2014.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim DK, Kang B, Kim OY, Choi DS, Lee J, Kim SR, Go G, Yoon YJ, Kim JH, Jang SC, Park KS, Choi EJ, Kim KP, Desiderio DM, Kim YK, Lötvall J, Hwang D, Gho YS. EVpedia: an integrated database of high-throughput data for systemic analyses of extracellular vesicles. J Extracell Vesicles. 2013;2 doi: 10.3402/jev.v2i0.20384. http://dx.doi.org/10.3402/jev.v2i0.20384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowald A, Kirkwood TB. Can aging be programmed? A critical literature review. Aging Cell. 2016 doi: 10.1111/acel.12510. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/acel.12510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Long X, Li Y, Yang M, Huang L, Gong W, Kuang E. BZLF1 attenuates transmission of inflammatory paracrine senescence in epstein-Barr virus-Infected cells by downregulating tumor necrosis factor alpha. J Virol. 2016;90(17):7880–7893. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00999-16. http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JVI.00999-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machida T, Tomofuji T, Ekuni D, Maruyama T, Yoneda T, Kawabata Y, Mizuno H, Miyai H, Kunitomo M, Morita M. MicroRNAs in salivary exosome as potential biomarkers of aging. Int J Mol Sci. 2015;16(9):21294–21309. doi: 10.3390/ijms160921294. http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/ijms160921294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathivanan S, Ji H, Simpson RJ. Exosomes: extracellular organelles important in intercellular communication. J Proteomics. 2010;73(10):1907–1920. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2010.06.006. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jprot.2010.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazloom H, Alizadeh S, Esfahani EN, Razi F, Meshkani R. Decreased expression of microRNA-21 is associated with increased cytokine production in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) of obese type 2 diabetic and non-diabetic subjects. Mol Cell Biochem. 2016;419(1–2):11–17. doi: 10.1007/s11010-016-2743-9. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11010-016-2743-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meder B, Backes C, Haas J, Leidinger P, Stähler C, Großmann T, Vogel B, Frese K, Giannitsis E, Katus HA, Meese E, Keller A. Influence of the confounding factors age and sex on microRNA profiles from peripheral blood. Clin Chem. 2014;60(9):1200–1208. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2014.224238. http://dx.doi.org/10.1373/clinchem.2014.224238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menon R. Human fetal membranes at term: dead tissue or signalers of parturition? Placenta. 2016;44:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2016.05.013. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.placenta.2016.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer SU, Pfaffl MW, Ulbrich SE. Normalization strategies for microRNA profiling experiments: a ‘normal’ way to a hidden layer of complexity? Biotechnol. Lett. 2010;32(12):1777–1788. doi: 10.1007/s10529-010-0380-z. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10529-010-0380-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosteiro L, Pantoja C, Alcazar N, Marión RM, Chondronasiou D, Rovira M, Fernandez-Marcos PJ, Muñoz-Martin M, Blanco-Aparicio C, Pastor J, Gómez-López G, De Martino A, Blasco MA, Abad M, Serrano M. Tissue damage and senescence provide critical signals for cellular reprogramming in vivo. Science. 2016;354(6315) doi: 10.1126/science.aaf4445. http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.aaf4445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura J, Mutlu E, Sharma V, Collins L, Bodnar W, Yu R, Lai Y, Moeller B, Lu K, Swenberg J. The endogenous exposome. DNA Repair (Amst) 2014;19:3–13. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2014.03.031. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.dnarep.2014.03.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noren Hooten N, Abdelmohsen K, Gorospe M, Ejiogu N, Zonderman AB. Evans MK microRNA expression patterns reveal differential expression of target genes with age. PLoS One. 2010;5(5):e10724. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010724. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0010724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noren Hooten N, Fitzpatrick M, Wood WH, 3rd, De S, Ejiogu N, Zhang Y, Mattison JA, Becker KG, Zonderman AB, Evans MK. Age-related changes in microRNA levels in serum. Aging (Albany NY) 2013;5(10):725–740. doi: 10.18632/aging.100603. http://dx.doi.org/10.18632/aging.100603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olivieri F, Spazzafumo L, Santini G, Lazzarini R, Albertini MC, Rippo MR, Galeazzi R, Abbatecola AM, Marcheselli F, Monti D, Ostan R, Cevenini E, Antonicelli R, Franceschi C, Procopio AD. Age-related differences in the expression of circulating microRNAs: miR-21 as a new circulating marker of inflammaging. Mech Ageing Dev. 2012;133(11–12):675–685. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2012.09.004. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.mad.2012.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olivieri F, Rippo MR, Monsurrò V, Salvioli M, Capri S, Procopio AD, Franceschi C. MicroRNAs linking inflamm-aging, cellular senescence and cancer. Ageing Res Rev. 2013;12(4):1056–1068. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2013.05.001. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2013.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olivieri F, Bonafè M, Spazzafumo L, Gobbi M, Prattichizzo F, Recchioni R, Marcheselli F, La Sala L, Galeazzi R, Rippo MR, Fulgenzi G, Angelini S, Lazzarini R, Bonfigli AR, Brugè F, Tiano L, Genovese S, Ceriello A, Boemi M, Franceschi C, Procopio AD, Testa R. Age- and glycemia-related miR-126-3p levels in plasma and endothelial cells. Aging (Albany NY) 2014a;6(9):771–787. doi: 10.18632/aging.100693. http://dx.doi.org/10.18632/aging.100693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olivieri F, Antonicelli R, Spazzafumo L, Santini G, Rippo MR, Galeazzi R, Giovagnetti S, D’Alessandra Y, Marcheselli F, Capogrossi MC, Procopio AD. Admission levels of circulating miR-499-5p and risk of death in elderly patients after acute non-ST elevation myocardial infarction. Int J Cardiol. 2014b;172(2):e276–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2013.12.203. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2013.12.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olivieri F, Albertini MC, Orciani M, Ceka A, Cricca M, Procopio AD, Bonafè M. DNA damage response (DDR) and senescence: shuttled inflamma-miRNAs on the stage of inflamm-aging. Oncotarget. 2015a;6(34):35509–35521. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.5899. http://dx.doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.5899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olivieri F, Spazzafumo L, Bonafè M, Recchioni R, Prattichizzo F, Marcheselli F, Micolucci L, Mensà E, Giuliani A, Santini G, Gobbi M, Lazzarini R, Boemi M, Testa R, Antonicelli R, Procopio AD, Bonfigli AR. MiR-21-5p and miR-126a-3p levels in plasma and circulating angiogenic cells: relationship with type 2 diabetes complications. Oncotarget. 2015b;6(34):35372–35382. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.6164. http://dx.doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.6164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ovchinnikova ES, Schmitter D, Vegter EL, Ter Maaten JM, Valente MA, Liu LC, van der Harst P, Pinto YM, de Boer RA, Meyer S, Teerlink JR, O’Connor CM, Metra M, Davison BA, Bloomfield DM, Cotter G, Cleland JG, Mebazaa A, Laribi S, Givertz MM, Ponikowski P, van der Meer P, van Veldhuisen DJ, Voors AA, Berezikov E. Signature of circulating microRNAs in patients with acute heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2016;18(4):414–423. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.332. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/ejhf.332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pincus Z, Smith-Vikos T, Slack FJ. MicroRNA predictors of longevity in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS Genet. 2011;7(9):e1002306. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002306. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1002306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponomaryova AA, Morozkin ES, Rykova EY, Zaporozhchenko IA, Skvortsova TE, Dobrodeev Zavyalov AYAA, Tuzikov SA, Vlassov VV, Cherdyntseva NV, Laktionov PP, Choinzonov EL. Dynamic changes in circulating miRNA levels in response to antitumor therapy of lung cancer. Exp Lung Res. 2016;42(2):95–102. doi: 10.3109/01902148.2016.1155245. http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/01902148.2016.1155245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salvioli S, Monti D, Lanzarini C, Conte M, Pirazzini C, Bacalini MG, Garagnani P, Giuliani C, Fontanesi E, Ostan R, Bucci L, Sevini F, Yani SL, Barbieri A, Lomartire L, Borelli V, Vianello D, Bellavista E, Martucci M, Cevenini E, Pini E, Scurti M, Biondi F, Santoro A, Capri M, Franceschi C. Immune system, cell senescence, aging and longevity? inflamm-aging reappraised. Curr Pharm Des. 2013;19(9):1675–1679. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato F, Tsuchiya S, Terasawa K, Tsujimoto G. Intra-platform repeatability and inter-platform comparability of microRNA microarray technology. PLoS One. 2009;4(5):e5540. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005540. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0005540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serna E, Gambini J, Borras C, Abdelaziz KM, Belenguer A, Sanchis P, Avellana JA, Rodriguez-Mañas L, Viña J. Centenarians, but not octogenarians, up-regulate the expression of microRNAs. Sci Rep. 2012;2:961. doi: 10.1038/srep00961. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/srep00961 (Erratumin: SciRep.2013;3:1575. Mohammed, Kheira [corrected to Abdelaziz, Kheira M]) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson RJ, Jensen SS, Lim JW. Proteomic profiling of exosomes: current perspectives. Proteomics. 2008;8(19):4083–4099. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200800109. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/pmic.200800109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson RJ, Lim JW, Moritz RL, Mathivanan S. Exosomes: proteomic insights and diagnostic potential. Expert Rev Proteomics. 2009;6(3):267–283. doi: 10.1586/epr.09.17. http://dx.doi.org/10.1586/epr.09.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith-Vikos T, Liu Z, Parsons C, Gorospe M, Ferrucci L, Gill TM, Slack FJ. A serum miRNA profile of human longevity: findings from the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging (BLSA) Aging (Albany NY) 2016 doi: 10.18632/aging.101106. http://dx.doi.org/10.18632/aging.101106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Spazzafumo L, Olivieri F, Abbatecola AM, Castellani G, Monti D, Lisa R, Galeazzi R, Sirolla C, Testa R, Ostan R, Scurti M, Caruso C, Vasto S, Vescovini R, Ogliari G, Mari D, Lattanzio F, Franceschi C. Remodelling of biological parameters during human ageing: evidence for complex regulation in longevity and in type 2 diabetes. Age (Dordr) 2013;35(2):419–429. doi: 10.1007/s11357-011-9348-8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11357-011-9348-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su DM, Aw D, Palmer DB. Immunosenescence: a product of the environment? Curr. Opin Immunol. 2013;25(4):498–503. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2013.05.018. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.coi.2013.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terry DF, Wilcox MA, McCormick MA, Pennington JY, Schoenhofen EA, Andersen SL, Perls TT. Lower all-cause, cardiovascular, and cancer mortality in centenarians’ offspring. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(12):2074–2076. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52561.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52561.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thakur BK, Zhang H, Becker A, Matei I, Huang Y, Costa-Silva B, Zheng Y, Hoshino A, Brazier H, Xiang J, Williams C, Rodriguez-Barrueco R, Silva JM, Zhang W, Hearn S, Elemento O, Paknejad N, Manova-Todorova K, Welte K, Bromberg J, Peinado H, Lyden D. Double-stranded DNA in exosomes: a novel biomarker in cancer detection. Cell Res. 2014;24(6):766–769. doi: 10.1038/cr.2014.44. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/cr.2014.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turchinovich A, Burwinkel B. Distinct AGO1 and A.G.O.2 associated miRNA profiles in human cells and blood plasma. RNA Biol. 2012;9(8):1066–1075. doi: 10.4161/rna.21083. http://dx.doi.org/10.4161/rna.21083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turchinovich A, Weiz L, Langheinz A, Burwinkel B. Characterization of extracellular circulating microRNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39(16):7223–7233. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr254. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkr254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Balkom BW, de Jong OG, Smits M, Brummelman J, den Ouden K, de Bree PM, van Eijndhoven MA, Pegtel DM, Stoorvogel W, Würdinger T, Verhaar MC. Endothelial cells require miR-214 to secrete exosomes that suppress senescence and induce angiogenesis in human and mouse endothelial cells. Blood. 2013;121(19):3997–4006. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-02-478925. http://dx.doi.org/10.1182/blood-2013-02-478925 (S1-15) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viña J, Borras C, Gomez-Cabrera MC. Overweight, obesity, and all-cause mortality. JAMA. 2013;309(16):1679. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.3080. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jama.2013.3080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vickers KC, Remaley AT. Lipid-based carriers of microRNAs and intercellular communication. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2012;23(2):91–97. doi: 10.1097/MOL.0b013e328350a425. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/MOL.0b013e328350a425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner J, Riwanto M, Besler C, Knau A, Fichtlscherer S, Röxe T, Zeiher AM, Landmesser U, Dimmeler S. Characterization of levels and cellular transfer of circulating lipoprotein-bound microRNAs. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2013;33(6):1392–1400. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.112.300741. http://dx.doi.org/10.1161/ATVBAHA.112.300741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner DR, Devaux Y, Collignon O. Door-to-balloon time and mortality. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(2):180–181. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1313113. http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMc1313113#SA5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner KH, Cameron-Smith D, Wessner B, Franzke B. Biomarkers of aging: from function to molecular biology. Nutrients. 2016;8(6):E338. doi: 10.3390/nu8060338. http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/nu8060338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang F, Long G, Zhao C, Li H, Chaugai S, Wang Y, Chen C, Wang DW. Atherosclerosis-related circulating miRNAs as novel and sensitive predictors for acute myocardial infarction. PLoS One. 2014;9(9):e105734. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0105734. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0105734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weilner S, Schraml E, Redl H, Grillari-Voglauer R, Grillari J. Secretion of microvesicular miRNAs in cellular and organismal aging. Exp Gerontol. 2013;48(7):626–633. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2012.11.017. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.exger.2012.11.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weilner S, Keider V, Winter M, Harreither E, Salzer B, Weiss F, Schraml E, Messner P, Pietschmann P, Hildner F, Gabriel C, Redl H, Grillari-Voglauer R, Grillari J. Vesicular Galectin-3 levels decrease with donor age and contribute to the reduced osteo-inductive potential of human plasma derived extracellular vesicles. Aging (Albany NY) 2016;8(1):16–33. doi: 10.18632/aging.100865. http://dx.doi.org/10.18632/aging.100865, Erratum in: Aging (Albany NY). 2016;8(5):1156–1157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiner-Gorzel K, Dempsey E, Milewska M, McGoldrick A, Toh V, Walsh A, Lindsay S, Gubbins L, Cannon A, Sharpe D, O’Sullivan J, Murphy M, Madden SF, Kell M, McCann A, Furlong F. Overexpression of the microRNA miR-433 promotes resistance to paclitaxel through the induction of cellular senescence in ovarian cancer cells. Cancer Med. 2015;4(5):745–758. doi: 10.1002/cam4.409. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/cam4.409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westendorp RG, van Heemst D, Rozing MP, Frölich M, Mooijaart SP, Blauw GJ, Beekman M, Heijmans BT, de Craen AJ, Slagboom PE Leiden Longevity Study Group. Nonagenarian siblings and their offspring display lower risk of mortality and morbidity than sporadic nonagenarians: the Leiden Longevity Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(9):1634–1637. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02381.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02381.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wild CP. Complementing the genome with an exposome: the outstanding challenge of environmental exposure measurement in molecular epidemiology. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14:1847–1850. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0456. http://dx.doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965 (EPI-05-0456) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witwer KW. Circulating microRNA biomarker studies: pitfalls and potential solutions. Clin Chem. 2015;61(1):56–63. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2014.221341. http://dx.doi.org/10.1373/clinchem.2014.221341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia S, Zhang X, Zheng S, Khanabdali R, Kalionis B, Wu J, Wan W, Tai XJ. An update on inflamm-Aging: mechanisms, prevention, and treatment. J Immunol Res. 2016;2016:8426874. doi: 10.1155/2016/8426874. http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2016/8426874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zampetaki A, Kiechl S, Drozdov I, Willeit P, Mayr U, Prokopi M, Mayr A, Weger S, Oberhollenzer F, Bonora E, Shah A, Willeit J, Mayr M. Plasma microRNA profiling reveals loss of endothelial miR-126 and other microRNAs in type 2 diabetes. Circ Res. 2010;107(6):810–817. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.226357. http://dx.doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.226357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Yang H, Zhang C, Jing Y, Wang C, Liu C, Zhang R, Wang J, Zhang J, Zen K, Zhang C, Li D. Investigation of microRNA expression in human serum during the aging process. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2015;70(1):102–109. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glu145. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/gerona/glu145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Liu YJ, Liu T, Zhang H, Yang SJ. Plasma microRNA-21 is a potential diagnostic biomarker of acute myocardial infarction. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2016;20(2):323–329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]