Abstract

Background

We report the ability to extend lung preservation up to 24 hours (24H) by using autologous whole donor blood circulating within an ex vivo lung perfusion (EVLP) system. This approach facilitates donor lung reconditioning in a model of extended normothermic EVLP. We analyzed comparative responses to cellular and acellular perfusates to identify these benefits.

Methods

Twelve pairs of swine lungs were retrieved after cardiac arrest and studied for 24H on the Organ Care System (OCS) Lung EVLP platform. Three groups (n=4 each) were differentiated by perfusate: (1) isolated red blood cells (RBCs) (current clinical standard for OCS); (2) whole blood (WB); and (3) acellular buffered dextran-albumin solution (BDAS, analogous to STEEN solution).

Results

Only the RBC and WB groups met clinical standards for transplantation at 8 hours; our primary analysis at 24H focused on perfusion with WB versus RBC. The WB perfusate was superior (vs. RBC) for maintaining stability of all monitored parameters, including the following mean 24H measures: pulmonary artery pressure (6.8 vs. 9.0 mmHg), reservoir volume replacement (85 vs. 1607 mL), and PaO2:FiO2 ratio (541 vs. 223). Acellular perfusion was limited to 6 hours on the OCS system due to prohibitively high vascular resistance, edema, and worsening compliance.

Conclusions

The use of an autologous whole donor blood perfusate allowed 24H of preservation without functional deterioration and was superior to both RBC and BDAS for extended lung preservation in a swine model using OCS Lung. This finding represents a potentially significant advance in donor lung preservation and reconditioning.

INTRODUCTION

Today, despite a steady increase in the number of patients listed for lung transplantation, less than 20% of lungs offered are transplanted. Ex vivo lung perfusion (EVLP) may increase donor yield by monitoring and reconditioning extended-criteria donor lungs.1,2 However, the safety of extended preservation with EVLP is currently unknown.

Devices currently approved for human use preserve lungs outside of the body for ~3–6H. They use a variety of perfusates: XVIVO Perfusion System (XPS, XVIVO Perfusion AB, Göteborg, Sweden) utilizes acellular STEEN solution (Vitrolife, Gothenburg, Sweden), the Vivoline System (Vivoline Medical AB, Lund, Sweden) uses STEEN and packed red blood cells (RBCs), and the Organ Care System Lung (OCS, TransMedics, Andover, MA, USA) uses packed RBCs diluted in OCS Lung solution (OCS solution).3,4

Animal studies and some human case reports have demonstrated successful EVLP over longer intervals. Cypel and colleagues successfully preserved human and swine lungs for 12 hours on the XVIVO platform.5 The INSPIRE trial showed the safety of OCS preservation for a mean of 4H and improved clinical outcomes compared with cold storage.4,6 Ceulemans and colleagues perfused human lungs up to 11H on OCS for a successful combined lung-liver transplant.7 The FDA-approval EXPAND trial, which makes use of OCS for extended-criteria donors, is currently enrolling human subjects with an EVLP interval limit of 12H.8,9

These intervals and perfusion strategies are effective for recruitment maneuvers, transportation (in the case of OCS), and assessment of most standard and extended-criteria donor lungs. However, injured lungs that require reconditioning may not be ready for transplant within this timeframe.2 The current study evaluates three perfusates for 24H EVLP on OCS: RBCs without plasma, autologous whole donor blood, and acellular buffered dextran-albumin solution (BDAS). It demonstrates that the safe interval for extended preservation of swine lungs is longer than that currently in use for human lung transplantation.

METHODS

Animals

The study was approved by the local Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Animals received humane care in compliance with the Principles of Laboratory Animal Care and Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Lungs were procured from castrated male Yorkshire swine (mean weight 82.5±7.4 kg), which underwent general anesthesia with isoflurane. Baseline arterial blood gases (ABGs) were measured. The lungs were ventilated with a positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) of 5mmHg and tidal volume (TV) of 8cc/kg.

Procurement

Following sternotomy, an aortic root cannula was placed for cardioplegia administration. After ruling out gross pulmonary abnormalities, 30,000 units of heparin were administered and allowed to circulate for 3 minutes, followed by collection of 1.5L of blood from the inferior vena cava (IVC). To achieve cardiac arrest in a manner consistent with clinical heart-lung procurement, the aorta was cross-clamped and cold cardioplegia (St. Thomas’ Hospital Cardioplegia: 1000mL contains 6.43g NaCl [220.05mM], 1.19g KCl [32.06mM], 0.18g CaCl2•2H2O [2.38mM], 3.25g MgCl2•6H2O [68.37mM], and 0.84g NaHCO3 [20.00mM]) was delivered through the aortic root with left atrial appendage venting.

Ventilation continued at 6cc/kg TV. Ice slush was placed around the heart and lungs. 2L of cold (4°C) OCS solution was administered through the main pulmonary artery (50mg nitroglycerin in first liter). 1L of OCS solution contains 50g dextran 40 [1.25mM], 2g glucose monohydrate [10.1mM], 0.201g MgSO4•7H2O [0.82mM], 0.4g KCl [10.23mM], 8g NaCl [136.89mM], 0.058g Na2HPO4•2H2O [0.33mM], and 0.063g KH2PO4 [0.46mM]. Lungs were procured en bloc while maintaining inflation.

Blood collection

To obtain leukocyte-reduced RBCs (RBC group), blood drained from the IVC was routed to an autoLog® Autotransfusion System (Medtronic PLC, Minneapolis, MN, USA).10 RBCs were recovered and rinsed with saline according to standard guidelines. The OCS was primed with 900ml of isolated RBCs and 1500ml of OCS solution, after passage through a leukocyte filter. For autologous whole blood collection (whole blood group), 1600ml of whole blood drained from the IVC, along with an additional 800ml of OCS Lung solution, was passed through a leukocyte filter and added to the OCS reservoir.

Finally, BDAS (acellular group) was produced fresh for each experiment using the published composition of STEEN solution (1000ml contains 5g dextran 40 [0.125mM], 70g bovine serum albumin [1.05mM], 5.03g NaCl [85.90mM], 0.24g glucose monohydrate [1.21mM], 0.34g KCl [4.56mM], 0.19g NaH2PO4•2H2O [1.22mM], 0.22g CaCl2•2H2O [1.50mM], 0.24g MgCl2•6H2O [2.52mM], 1.26g NaHCO3 [15.00mM], and adjustment to a pH 7.4 with 1M NaOH).11,12 The circuit was primed only with 2400ml of BDAS.

Instrumentation and Perfusion

A cold retrograde flush of 1L OCS solution was administered through the pulmonary vein ostia. While maintaining inflation, the trachea and main pulmonary artery (PA) were cannulated. The device was primed as above before loading the lungs onto the perfusion chamber. Standard OCS Lung additives (1g cefazolin, 200mg ciprofloxacin, 200mg voriconazole, 500mg methylprednisolone, 1 vial multivitamins, 20 IU regular insulin, 4mg milrinone, 20mEq NaHCO3, and 50 mg nitroglycerin) were added to the perfusate in all three groups.

Next, the lungs were installed into the OCS perfusion chamber. For the initial 30-minute assessment period, flow was slowly increased to a goal of 2.0–2.5L/min. The lungs rewarmed to 37°C and ventilation was resumed (TV 6cc/kg, PEEP 7mmHg, respiratory rate of 10 breaths/min). To allow for rewarming, the first arterial blood gas was measured 30 minutes after the start of perfusion, the arbitrary “0 hour” time point. ABG sampling was performed at 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, and 24H. Samples were analyzed using a GEM® 3000 device (Instrumentation Laboratory, Bedford, MA, USA) and the PaO2:FiO2 ratio (P:F) was calculated.

Throughout the experiments, pulmonary artery pressures (PAP), vascular resistance (VR), oxygen saturation, temperature, peak airway pressure (PAWP), TV, and hematocrit (HCT) were continuously monitored. Dynamic compliance (DC) was calculated using the formula DC=TV/(PAWP-PEEP). Elevations in VR over the first 30 minutes were treated with 10mg infusions of nitroglycerin and as needed later in the experiment to maintain the mean PAP <20mmHg and to allow increases in flow for assessment.

Oxygen saturation probes were placed on both the inflow (from the oxygenator toward the PA) and outflow (from the lung basin drain toward the oxygenator) tubing. During preservation, the oxygenator and ventilator were supplied by a 12% O2 tank and flow was maintained at 1.5–1.75L/min per established guidelines. During assessment, flow was increased to 2.0–2.5L/min and the oxygenator was flushed with a 6% CO2/balanced N2 gas mixture and the lungs were ventilated with 21% O2, supplying deoxygenated blood to the lungs and allowing assessment of graft oxygenation. Goal flows during assessment and preservation were standard for all animals.

Reservoir volumes were checked and supplemented with additional OCS solution, as needed, to maintain ≥500ml in the reservoir. NaHCO3 and dextrose were administered as needed throughout to maintain bicarbonate levels >20meq/L and glucose levels >70mg/dL. Pulmonary edema was assessed using lung block weights (before and after EVLP), HCT, and reservoir volume replacement (RVR), as well as gross inspection and flexible bronchoscopy. At the completion of each experiment, the lungs were photographed, flushed with 1L of OCS Lung solution, and tissue specimens collected.

Baseline analysis of inflammation

To determine the baseline level of inflammatory activation in blood perfusates, we analyzed baseline aliquots of isolated RBC, autologous whole donor blood (whole blood), and whole blood after passage through a leukocyte filter (LF, whole blood post-LF). We compared cell counts, inflammatory activation, and cytokine release.

Flow cytometry

Cells were diluted 1:100 with 1X phosphate-buffered saline and collected using a Becton Dickson LSRII (BD Bioscience, San Jose, CA, USA). Forward versus side scatter plots were generated using FlowJo software (FlowJo, Ashland, OR, USA).

qRT-PCR

Blood samples were homogenized in Trizol (Thermo Fisher, Grand Island, NY, USA). RNA was extracted following manufacturer’s protocol and quantitated using a nanophotometer (Implemen, Westlake Village, CA, USA). cDNA was then generated using the Invitrogen Superscript kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). qPCR using probes (Applied Biosystems, Grand Island, NY, USA) against Swine Leukocyte Antigen DR-Alpha (SLA-DR)(Ss03389945_m1) and Cluster of Differentiation 69 (CD69)(Ss03394001_m1) was performed on an ABI7500 machine (Blue Lion Biotech, Carnation, WA, USA).

Cytokine analysis

Aliquots of the three different perfusate groups were assessed for cytokine release. Interleukins (IL)-1b, 6, 8 and 10 were analyzed on the Luminex platform (Luminex, Austin, TX, USA) using bead sets from Millipore (Billerica, CA, USA).

Statistical analysis

Preliminary analyses on variables measured every 2 minutes by the OCS Lung (DC, HCT, SaO2, SvO2, VR, and mean PAP) were done using linear mixed models to determine the frequency of measurements providing maximum power in the main analyses. Hourly measurements yield near optimal power for all outcomes and, as such, were analyzed using hourly measurements, over 24H to compare RBCs and whole blood and over the first 6H to compare all three perfusates for the main analyses. VR was also analyzed over the first thirty minutes using measurements at two-minute increments to compare RBCs versus whole blood. P:F was analyzed using all available measurements, at 0, 2, 4, and 6H to compare RBCs versus whole blood, and at 0, 2, and 4H for a three-group comparison. Lactate and pH were analyzed using all available measurements, at 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, and 24H, to compare RBCs versus whole blood.

Each analysis used a mixed linear model implemented in SAS’s MIXED procedure (SAS Institute Inc., Cary NC USA), with an exponential correlation structure (SP(EXP) in the MIXED procedure) to account for temporal dependence between measurements on a pair of lungs. Adjusted averages (accounting for missing observations, as needed) and standard errors at each time were calculated and plotted for each perfusate group. Statistical tests assessed (1) differences between groups in group averages over all time points (“Group Effect p”), (2) differences between groups in the pattern over time (“Global Interaction p”), and (3) differences between groups at single times, indicated by marks on the horizontal axis time labels ([’] for p<0.05, [”] for p<0.01, and (*) for p<0.001). For the 6H/three-group comparisons, tests were done comparing group averages across time for STEEN versus RBCs and versus whole blood. P-values were not adjusted for multiple comparisons. Lung block weight, starting osmolality, RVR, and measures of inflammatory expression were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA, α = 0.05) using GraphPad Prism 6 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA). Numeric data were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation.

RESULTS

All procurements and EVLP runs were technically successful, with a mean time from procurement to initial perfusion of 20 minutes. At baseline, all lungs appeared healthy, with equal bilateral ventilation, compliance, and recoil.

24H perfusion: RBC versus Whole Blood

Perfusion

The acellular experiments are described separately. In all cellular experiments, goal flow rates for preservation and ABG assessment were achieved. The trend of lactate production was similar in both cellular groups, with greater overall production in the whole blood group (p<0.05, Figure 1A). pH was maintained in each cellular group with the addition of NaHCO3, although it was generally lower in the RBC group (p<0.01, Figure 1B). Administration of NaHCO3 and dextrose was volumetrically similar in the cellular groups over 24H. More dextrose replacement was required in the whole blood group (9.2±1.7g vs. 3.3±1.9g).

Figure 1.

Metabolic and initial perfusion characteristics on OCS Lung. (A) Over the initial 12 hours, lactic acid production steadily increased in both groups and overall lactate production was significantly greater in the whole blood group. (B) pH remained essentially stable in each group with the addition of bicarbonate, but was slightly lower throughout in the RBC group. (C) At the start of EVLP, VR decreased as the lungs recovered from cold ischemia and gradually rewarmed to 37°C. Ventilation was initiated at approximately 10 minutes after the start of perfusion and the initial assessment was performed at 30 minutes. There was no significant difference in initial or 30-minute VR between groups. RBC: packed red blood cells; OCS = Organ Care System; VR: vascular resistance

Pulmonary physiology

VR was universally elevated at the start of EVLP but recovered by 20 minutes of perfusion (Figure 1C). In the whole blood group, VR steadily decreased over 24H (Figure 2A). In the RBC group, VR rose sharply after 8H of perfusion (p<0.0001). PAP gradually decreased and DC gradually increased with time in the whole blood group, while the opposite was observed in the RBC group (Figures 2B–C). DC had a better initial trend in the RBC group but this reversed at 10H of perfusion (p<0.05). Frothy airway edema usually developed around this time, likely a contributing factor to this finding.

Figure 2.

Improved physiologic parameters in lungs perfused with autologous whole blood. (A) Pulmonary vascular resistance (B) Mean pulmonary artery pressure. (C) Dynamic compliance. Dynamic compliance = DC = TV/(PAWP - PEEP). TV: tidal volume; PAWP: peak airway pressure; PEEP: positive end-expiratory pressure

Oxygenation

P:F is an important indicator of general lung function and quality and a value of ≥300 is considered standard for acceptance in clinical transplantation. In this study, both groups had a similar P:F up to 6H, indicating suitability for transplantation (Figure 3A). However, beyond this point, P:F was undetectable in all but one of the RBC groups due to edema and intolerance of assessment flow rates. In the whole blood group, the mean P:F steadily improved over 24H (Figures 3C). Measured systemic arterial (SaO2) and venous (SvO2) oxygen saturation was maintained over 24H in the whole blood group, while each deteriorated after 12H in the RBC group (Figures 3B and 3D).

Figure 3.

Improved oxygenation in lungs perfused with autologous whole blood. (A) Serum P:F ratios over the first 6H of EVLP. This did not differ between groups at any time point over this interval. (B) Arterial O2 saturation (SaO2) over 24H. (C) Comparison of initial and final P:F ratios between groups. P:F was unmeasurable at 24H in all but one RBC experiment due to gross pulmonary edema. (D) Venous O2 saturation (SvO2). Note wide variability in SaO2 and SvO2 in the RBC group due to worsening frothy pulmonary edema beyond 12 hours. P:F: PaO2:FiO2; RBC: red blood cells.

Macroscopic and histologic assessment

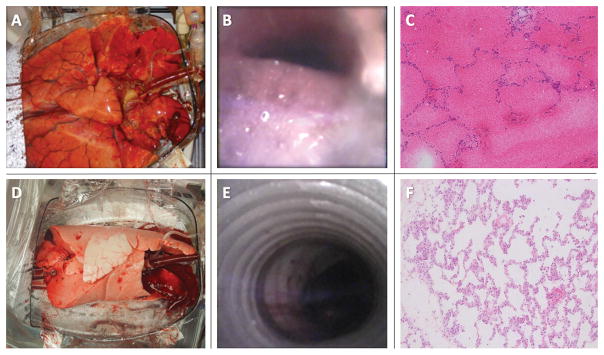

Global edema primarily occurred in the RBC group. Edema was appreciable on gross inspection by 12H and it became impressive by 24H (Figure 4A). Gross edema was minimal at 24H in the whole blood group (Figure 4D). These findings were confirmed on flexible bronchoscopy (Figures 4B and 4E). Histologic analysis after 24H showed diffuse alveolar hemorrhage and loss of interstitial architecture in the RBC group but normal architecture in the whole blood group (Figures 4C and 4F).

Figure 4.

24H of EVLP with RBC (top row) and autologous whole blood (bottom row). (A) Gross edema in a RBC group lung; note the dimensions of the lung chamber as compared with the lung volume at 24H. (B) Bronchoscopic demonstration of frothy edema in the trachea. (C). Histologic section of an RBC group lung after 24H of EVLP demonstrating diffuse alveolar hemorrhage and interstitial edema. (D) Normal-appearing lung after 24H of EVLP with autologous whole blood. (E) No evidence of gross edema after 24H with whole blood. (F) Normal histologic architecture after 24H of whole blood perfusion. EVLP: ex vivo lung perfusion; RBC: red blood cells

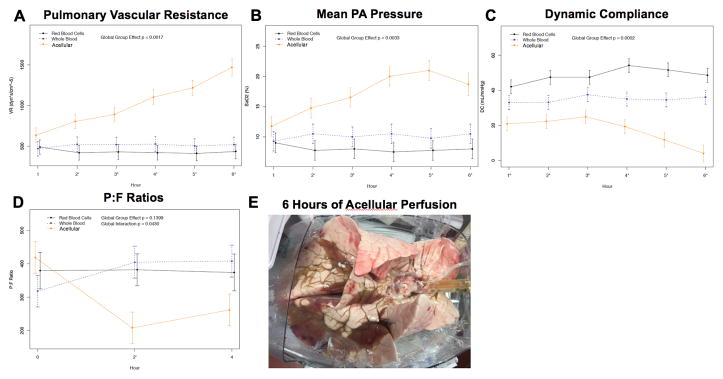

Acellular versus Cellular: 6H perfusion

VR increased markedly after 3H of perfusion in the acellular group. All acellular experiments (n=4) were aborted by 6H due to excessive VR, RVR, and profound edema (Figures 5A, 5B, 5E). By comparison, the VR was stable at 6H in both cellular groups with the lowest values noted in the RBC group (p<0.01). PAP also diverged at 2–3H and was highest in the acelluar group and lowest in the RBC group (p<0.01, Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

Comparison of acellular (n=4) versus cellular (n=8) perfusion. (A) VR was significantly elevated in the acellular group compared to both cellular groups. (B) mPAP mirrored the findings of vascular resistance. (C) PaO2:FiO2 (P:F) ratios are shown. Acellular P:F decreased in comparison with cellular perfusion. (D) DC was lowest in the acellular group at each time point. (E) Gross image of swine lung block with significant edema following 6H of acellular perfusion. Note that the size of the lung block approximates the dimension of the module. Dynamic compliance = (DC) = TV/(PAWP - PEEP). VR: vascular resistance; mPAP: mean pulmonary artery pressure; P:F: PaO2:FiO2 ratio; RBC: red blood cells; TV: tidal volume; PAWP: peak airway pressure; PEEP: positive end-expiratory pressure.

DC trended down in the acellular group after 3H, but remained stable in both cellular groups (p<0.001, Figure 5C). P:Fs in the cellular groups were consistently >300 over the first 6H but fell below this level in the acellular group after only 1–2H (Figure 5D). ABGs beyond 4H were unmeasurable in the acellular group. Gross pulmonary edema was obvious after 6H of acellular perfusion (Figure 5E).

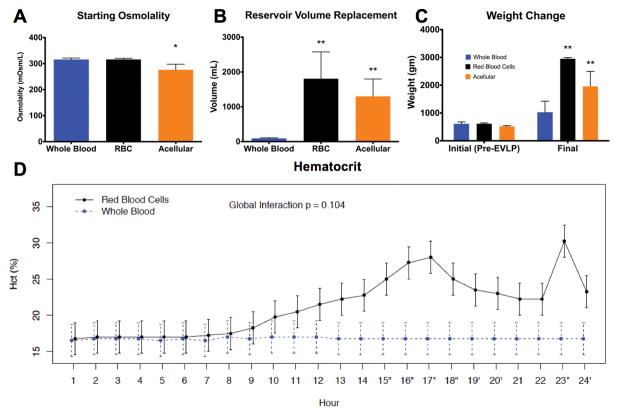

Pulmonary Edema during EVLP

Baseline osmolality and HCT levels were similar between both cellular groups (Figures 6A and 6D). The baseline osmolality in the acellular group was slightly lower than the others (p<0.05, Figure 6A). Beyond 8H, HCT increased in the RBC group, suggesting progressive edema. HCT remained stable in the whole blood group over 24H (Figure 6D).

Figure 6.

Decreased pulmonary edema after autologous whole blood perfusion. (A) Plot of baseline osmolality values (n=4 for each group). Findings show no difference between cellular groups, but the acellular group started at lower osmolality. (B) Reservoir volume replacement was significantly increased in the RBC and acellular groups compared to autologous whole blood, also reflecting parenchymal fluid loss. (C) Final lung block weight was significantly increased in the RBC and acellular groups compared to the autologous whole blood groups after EVLP. Note that “final” signifies 24H for cellular groups and 6H for the acellular group. (D) Hematocrit was similar between the whole blood and RBC groups over the initial 8H, but increased after this point in the RBC group, suggesting ongoing fluid loss into the lung parenchyma. Hematocrit was necessarily unmeasurable in the acellular group. RBC: red blood cells; EVLP: ex vivo lung perfusion.

Reservoir volume replacement (RVR) is a sensitive predictor of pulmonary edema. Figure 6B shows the net RVR over the course of the experiments (24H for cellular and 6H for acellular). During the initial 6–8H, RVR in the RBC group was minimal but increased significantly after this point and repeated boluses or continuous drips of OCS solution were required to maintain any volume in the reservoir. As such, volume requirements over 24H were significantly higher in the RBC group (p<0.05). The reservoir volume was stable over 24H in the whole blood group; the only volume added was that required for dextrose and NaHCO3 repletion. In the acellular group, RVR at 6H approximated that seen after 24H in the RBC group.

The mean weight of the lung blocks at the start of each experiment did not differ significantly between groups. The mean weight was 836±147g in the whole blood group and 2951±43g in the RBC group after 24H of EVLP (p<0.0001). The mean lung block weight was 1958±538g in the acellular group at 6H, significantly greater than the whole blood group at 24H (p<0.05, Figure 6C).

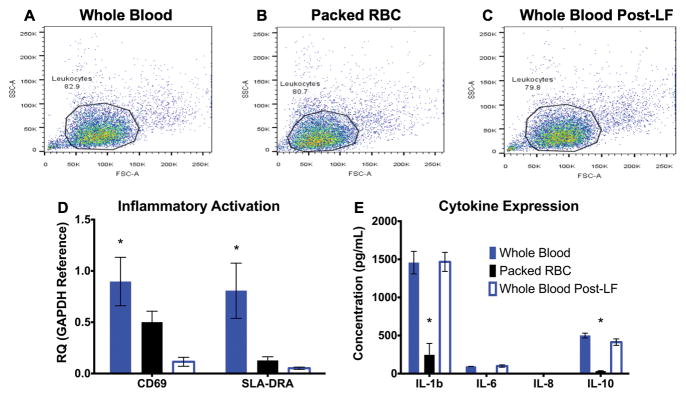

RBC Preparation, Leukocyte Filtration, and Inflammatory Activation

In order to determine whether RBC isolation and leukocyte filtration conferred any independent inflammatory insult, the relative concentrations and activation status of leukocytes, along with concentrations of relevant cytokines, were measured in samples of whole blood, whole blood passed through a leukocyte filter (LF), and RBCs isolated via cell salvage. All samples were obtained prior to EVLP. Flow cytometry demonstrated a consistent concentration of leukocytes in all three samples (Figures 7A–C). Expression of CD69 and SLA-DRA (early markers of T-cell activation and differentiation) mRNA was significantly lower in the RBC group compared with whole blood, suggesting that cell salvage did not cause inflammatory activation (Figure 7D).13,14 Whole blood post-LF had a lower amount of CD69 expression than the RBC group. SLA-DRA levels were low in both groups.

Figure 7.

Baseline comparison of inflammatory activation in autologous whole blood vs. RBC. (A–C) Whole blood, RBC, and whole blood post-LF all show similar inflammatory leukocyte counts. (D) Assessment of baseline cellular inflammatory activation. qRT-PCR analysis for CD69 and SLA-DRA suggest the highest levels of activated leukocytes exist in autologous whole blood, which is largely counteracted by filtration. SLA-DRA was similar in RBC vs. post-LF whole blood. (E) Serum inflammatory cytokines (Interleukins 1b, 6, 8 and 10) were greater in whole blood preparations compared with RBC. (*): p < 0.05 compared to each other group within the cytokine family. RBC: red blood cells; LF: leukocyte filter; qRT-PCR: quantitative reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction; CD: cluster of differentiation; SLA-DRA: Swine Leukocyte Antigen DR-Alpha; FSC: forward scatter parameter; SSC: side scatter parameter.

Concentrations of relevant cytokines (IL-1b, IL-6, IL-8, and IL-10) were also measured in each sample (Figure 7E). Passage through a leukocyte filter did not cause a significant decrease in cytokine concentration, but significant reductions were found in the RBC group (p<0.05). Overall, these data suggest that the RBC isolation does not create a pro-inflammatory milieu that was responsible for the increased lung injury observed during EVLP.

DISCUSSION

The principal finding of this study was that 24H of preservation using the OCS Lung in a swine model was possible only with autologous whole donor blood and not with RBC or BDAS perfusates. RBC perfusion without plasma in this configuration resulted in excellent initial performance, which supports its continued clinical use for standard donor lungs and short (<12H) perfusion intervals. Acellular perfusion was not compatible with this system beyond 2–3H of EVLP.

OCS Lung is currently the subject of two major international trials, INSPIRE and EXPAND, both of which utilize a packed RBC perfusate.4,6,9 Packed RBC is a logical choice; it limits viscosity, maximizes availability, and reduces interference with other transplant teams. Also, brain dead donors have an inflammatory response that might perpetuate cytokine-mediated injury during EVLP. However, the effects of brain death include volume shifts, endocrine changes, and catecholamine surges, all of which are reduced with EVLP, even in the presence of autologous whole donor blood.

What are the potential benefits of prolonged EVLP? Thus far, EVLP has been used as a screening and early recruitment tool.1,8 Lungs that do not demonstrate improvement within 4–6H are often not transplanted.15–17 However, there are many settings in which 4–6H of EVLP may be insufficient, including the presence of edema, contusions, infections, and other donor-related lung injuries. Mesenchymal stem cell, gene, and pharmacologic therapies require time for maximal effect. Donation after circulatory death (DCD) lungs suffer an unpredictable ischemia-reperfusion-induced injury that might benefit from prolonged EVLP assessment prior to transplant.18 Finally, clinical logistical issues can be alleviated with longer periods of time on EVLP.

Until now, the collateral insult caused by prolonged perfusion with acellular solutions or packed RBC has not been clearly demonstrated. In clinical practice, packed RBC units damaged by age or trauma harbor increased free hemoglobin, iron, and blood cell fragments.19,20 Iron and free heme produce oxidant-induced cellular damage.21 In culture, Qing and colleagues showed that lung endothelial cells undergo necrotic cell death with prolonged RBC exposure.22 In cardiac surgery, packed RBC transfusions have been linked to pulmonary dysfunction and decreased survival.23,24 Lungs appear to be susceptible to packed RBC-induced injury in critically ill patients.25,26

The reason why the RBC group did worse must also be, at least in part, due to the lack of plasma. The process of procurement and subsequent initiation of EVLP carries an ischemia-reperfusion insult that may lead to endothelial dysfunction, sequelae of which may be exacerbated by the disordered or absent fibrinolytic mechanisms inherent to an RBC-rich but plasma-poor perfusate27. Whole blood maintains clotting factors and platelets that prevent propagation of injury which may be important in EVLP platforms. The components in whole blood plasma may help to mitigate early injury before it becomes severe, but this question requires further investigation.

An EVLP platform is an unnatural environment for prolonged lung storage. No matter how well-designed, there is potential for parenchymal irritation, microvascular damage, regional malperfusion, and alveolar trauma. Although we did not directly measure indicators of hemolysis such as serum free hemoglobin or lactate dehydrogenase, there was no difference in serum potassium levels (also indicative of hemolysis) between groups at any time point in our study.

Other reasons for worse performance in the RBC group, such as protein concentration and inflammatory activation by cell salvage, were addressed. The baseline osmolality and hematocrit levels were similar. The inflammatory marker assays showed greater baseline inflammation in whole blood compared to RBCs. The increased CD69 in RBCs compared with post-LF whole blood will require further investigation as a potential inciting factor.

How do we explain the findings with acellular perfusion? Used as the perfusate in the XVIVO and Vivoline systems, STEEN solution has a composition that mimics the lung’s intravascular composition without RBCs. Vivoline does add RBC but the XVIVO system has had significant success without the use of RBC.3,5,15 It is difficult to compare and contrast these systems since they have inherently different designs. In the OCS device, flow and hematocrit sensors are optimized for performance using a blood-based perfusate. It is not intended for acellular perfusion.

Moreover, OCS uses an open left atrium, compared with XVIVO, which uses a closed atrium with controlled atrial pressures. Low pressure from an open left atrium can result in capillary collapse and pulmonary edema when the airway pressures increase.28–30 The OCS system maintains mean airway pressures well below the 15–20mmHg range, above which pulmonary edema is observed in rabbit models with low atrial pressures.29 Despite this, with all conditions being equal, the acellular perfusate performed significantly worse than the blood-based perfusates for extended preservation in this setting.

Limitations

These results may not be directly applicable to human lungs but provide a foundation for further investigation. Whole blood transfusion has been associated with favorable results in both civilian and military settings.31 It is conceivable that our results may be different with actual banked RBC. Study lungs were not transplanted after EVLP, preventing assessment of post-transplant performance. This was a preclinical evaluation to determine markers of successful preservation during prolonged EVLP. Subsequent studies will address the effects of prolonged preservation on a second ischemia-reperfusion injury occurring after transplant. In our clinical experience, there is no value in transplanting lungs that do not meet transplant criteria on OCS and, thus, it would not have been useful to transplant the prolonged packed RBC or acellular lungs. Finally, animals were sedated but not brain dead at the time of cardiac arrest and procurement. Future studies should address the relative effect of brain death on the blood used for EVLP.

CONCLUSION

Swine lungs exposed to prolonged perfusion on the OCS Lung system with autologous whole donor blood—but not with RBCs or an acellular STEEN-like solution—were viable for transplantation at 24H. RBC is the ideal perfusion strategy for short EVLP intervals (<10–12H) in healthy donor lungs. This has been supported in human clinical trials. However, for lungs requiring a longer period of reconditioning, serious consideration should be given to the use of whole blood. Future studies should address how the mode of donation (brain death vs. DCD) impacts the inflammatory milieu in the donor blood and whether this has an effect on prolonged EVLP.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Mary Knatterud, Ph.D., for manuscript editing, Phillip Meyers, CCP and Travis Day, CCP for help with the cell salvage system and establishing OCS perfusion in the animal lab, James Hodges, Ph.D, for assistance with statistical analysis, and Monica Mahre, B.S., for assistance with manuscript submission.

Alphabetical List of Abbreviations

- ABG

Arterial blood gas(es)

- ANOVA

Analysis of variance

- BDAS

Buffered dextran-albumin solution

- CD

Cluster of differentiation

- cDNA

Complimentary deoxyribonucleic acid

- DC

Dynamic compliance

- DCD

Donation after cardiac death

- EVLP

Ex vivo lung perfusion

- FDA

Food and Drug Administration

- FSC

Forward scatter parameter

- H

Hours

- HCT

Hematocrit

- IL

Interleukin

- IVC

Inferior vena cava

- LF

Leukocyte filter

- OCS

Organ Care System

- P:F

PaO2:FiO2 ratio

- PA

Pulmonary artery

- PAP

Pulmonary artery pressure

- PAWP

Peak airway pressure

- PEEP

Positive end-expiratory pressure

- qPCR

Quantitative polymerase chain reaction

- qRT-PCR

Quantitative reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction

- RBC

Red blood cell(s)

- RNA

Ribonucleic acid

- RVR

Reservoir volume replacement

- SaO2

Arterial oxygen saturation (%)

- SLA-DRA

Swine leukocyte antigen DR-alpha

- SSC

Side scatter parameter

- SvO2

Venous oxygen saturation (%)

- TV

Tidal volume

- VR

Vascular resistance

- WB

Whole blood

- XPS

XVIVO Perfusion System

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosure

This study was funded by grants from United Therapeutics Corporation (Silver Spring, MD, USA); the University of Minnesota’s Lillehei Heart Institute, Department of Surgery, and Institute for Engineering in Medicine; and by R01HL108627 awarded to Angela Panoskaltsis-Mortari. These funding organizations did not have any role in collecting, analyzing, or interpreting data or the decision to publish the manuscript.

Non-clinical grade disposable perfusion equipment was provided courtesy of TransMedics (Andover, MA, USA). This included the blood collection chambers, four reusable modules for animal work, and OCS Lung solution. The cell salvage device for RBC collection was provided courtesy of Medtronic PLC (Minneapolis, MN, USA). Dr. Loor is a co-investigator in the INSPIRE and EXPAND trials and receives grant support for these trials from TransMedics.

Author Contributions

GL: Intellectual conception of project, extensive literature review, data collection, data analysis, principal composition of manuscript, manuscript editing, final approval of manuscript

BTH: Intellectual conception of project, extensive literature review, data collection, data analysis, principal composition of manuscript, manuscript editing, final approval of manuscript

JRS: Intellectual conception of project, extensive literature review, data collection, data analysis, partial composition of manuscript, construction and revision of figures, manuscript editing, final approval of manuscript

LMM: Intellectual conception of project, data collection, data analysis, manuscript editing, final approval of manuscript

AP-M: Intellectual conception of project, data collection, data analysis, partial construction of figures, manuscript editing, final approval of manuscript

RZB: Data analysis, construction and revision of figures, manuscript editing, final approval of manuscript

TLI: Intellectual conception of project, data collection, manuscript editing, final approval of manuscript

CMM: Data collection, data analysis, partial construction of figures, manuscript editing, final approval of manuscript

HH: Data collection, data analysis, partial construction of figures, manuscript editing, final approval of manuscript

AP: Data collection, data analysis, partial construction of figures, manuscript editing, final approval of manuscript

PAI: Intellectual conception of project, data collection, data analysis, manuscript editing, final approval of manuscript

References

- 1.Fildes JE, Archer LD, Blaikley J, et al. Clinical Outcome of Patients Transplanted with Marginal Donor Lungs via Ex Vivo Lung Perfusion Compared to Standard Lung Transplantation. Transplantation. 2015;99(5):1078–1083. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000000462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roman MA, Nair S, Tsui S, Dunning J, Parmar JS. Ex vivo lung perfusion: a comprehensive review of the development and exploration of future trends. Transplantation. 2013;96(6):509–518. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e318295eeb7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cypel M, Yeung JC, Liu M, et al. Normothermic ex vivo lung perfusion in clinical lung transplantation. The New England journal of medicine. 2011;364(15):1431–1440. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1014597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Warnecke G, Moradiellos J, Tudorache I, et al. Normothermic perfusion of donor lungs for preservation and assessment with the Organ Care System Lung before bilateral transplantation: a pilot study of 12 patients. Lancet. 2012;380(9856):1851–1858. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61344-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cypel M, Yeung JC, Hirayama S, et al. Technique for prolonged normothermic ex vivo lung perfusion. The Journal of heart and lung transplantation : the official publication of the International Society for Heart Transplantation. 2008;27(12):1319–1325. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2008.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Warnecke G, Van Raemdonck D, Kukreja J, et al. The Organ Care System (OCS) Lung Inspire International Trial Results (abstract OLB05) Transplant Int. 2015;28(suppl 4):131. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ceulemans LJ, Monbaliu D, Verslype C, et al. Combined liver and lung transplantation with extended normothermic lung preservation in a patient with end-stage emphysema complicated by drug-induced acute liver failure. Am J Transplant. 2014;14(10):2412–2416. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Loor GWG, Smith M, Kukreja J, Ardehali A, Moradiellos J, Varela A, Madsen J, Hertz M, Van Raedonck The OCS Lung EXPAND International Trial Interim Results. The Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation. 2016;35(4):S68–S69. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Raemdonck DV, Warnecke G, Kukreja J, Smith M, Loor G, et al. The EXPAND Lung International Trial to Evaluate the Safety and Effectiveness of the Portable Organ Care System (OCS™) Lung for Recruiting, Preserving and Assessing Expanded Criteria Donor Lungs for Transplantation. The Journal of heart and lung transplantation : the official publication of the International Society for Heart Transplantation. 2014;33(4):S17–S18. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Serrick CJ, Scholz M, Melo A, Singh O, Noel D. Quality of red blood cells using autotransfusion devices: a comparative analysis. The Journal of extra-corporeal technology. 2003;35(1):28–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carnevale R, Biondi-Zoccai G, Peruzzi M, et al. New insights into the steen solution properties: breakthrough in antioxidant effects via NOX2 downregulation. Oxidative medicine and cellular longevity. 2014;2014:242180. doi: 10.1155/2014/242180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Steen S, assignee. iVA, assignee. Evaluation and preservation solution. 7,255,983 US patent. 2007 Aug 14;

- 13.Lee JH, Simond D, Hawthorne WJ, et al. Characterization of the swine major histocompatibility complex alleles at eight loci in Westran pigs. Xenotransplantation. 2005;12(4):303–307. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3089.2005.00231.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Simms PE, Ellis TM. Utility of flow cytometric detection of CD69 expression as a rapid method for determining poly- and oligoclonal lymphocyte activation. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1996;3(3):301–304. doi: 10.1128/cdli.3.3.301-304.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cypel M, Yeung JC, Machuca T, et al. Experience with the first 50 ex vivo lung perfusions in clinical transplantation. The Journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. 2012;144(5):1200–1206. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2012.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pierre L, Lindstedt S, Hlebowicz J, Ingemansson R. Is it possible to further improve the function of pulmonary grafts by extending the duration of lung reconditioning using ex vivo lung perfusion? Perfusion. 2013;28(4):322–327. doi: 10.1177/0267659113479424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sage E, Mussot S, Trebbia G, et al. Lung transplantation from initially rejected donors after ex vivo lung reconditioning: the French experience. European journal of cardio-thoracic surgery : official journal of the European Association for Cardio-thoracic Surgery. 2014;46(5):794–799. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezu245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Egan TM, Requard JJ., 3rd Uncontrolled Donation After Circulatory Determination of Death Donors (uDCDDs) as a Source of Lungs for Transplant. Am J Transplant. 2015 doi: 10.1111/ajt.13246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cywinski JB, You J, Argalious M, et al. Transfusion of older red blood cells is associated with decreased graft survival after orthotopic liver transplantation. Liver transplantation : official publication of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the International Liver Transplantation Society. 2013;19(11):1181–1188. doi: 10.1002/lt.23695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koch CG, Li L, Sessler DI, et al. Duration of red-cell storage and complications after cardiac surgery. The New England journal of medicine. 2008;358(12):1229–1239. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa070403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bansal S, Biswas G, Avadhani NG. Mitochondria-targeted heme oxygenase-1 induces oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction in macrophages, kidney fibroblasts and in chronic alcohol hepatotoxicity. Redox biology. 2014;2:273–283. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2013.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Qing DY, Conegliano D, Shashaty MG, et al. Red blood cells induce necroptosis of lung endothelial cells and increase susceptibility to lung inflammation. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2014;190(11):1243–1254. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201406-1095OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koch CG, Li L, Van Wagoner DR, Duncan AI, Gillinov AM, Blackstone EH. Red cell transfusion is associated with an increased risk for postoperative atrial fibrillation. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 2006;82(5):1747–1756. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2006.05.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Loor G, Rajeswaran J, Li L, et al. The least of 3 evils: exposure to red blood cell transfusion, anemia, or both? The Journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. 2013;146(6):1480–1487. e1486. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2013.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Corwin HL, Gettinger A, Pearl RG, et al. The CRIT Study: Anemia and blood transfusion in the critically ill--current clinical practice in the United States. Critical care medicine. 2004;32(1):39–52. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000104112.34142.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Croce MA, Tolley EA, Claridge JA, Fabian TC. Transfusions result in pulmonary morbidity and death after a moderate degree of injury. The Journal of trauma. 2005;59(1):19–23. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000171459.21450.dc. discussion 23–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Price LC, McAuley DF, Marino PS, Finney SJ, Griffiths MJ, Wort SJ. Pathophysiology of pulmonary hypertension in acute lung injury. American journal of physiology. Lung cellular and molecular physiology. 2012;302(9):L803–815. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00355.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Linacre V, Cypel M, Machuca T, et al. Importance of left atrial pressure during ex vivo lung perfusion. The Journal of heart and lung transplantation : the official publication of the International Society for Heart Transplantation. 2016;35(6):808–814. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2016.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Broccard AF, Vannay C, Feihl F, Schaller MD. Impact of low pulmonary vascular pressure on ventilator-induced lung injury. Critical care medicine. 2002;30(10):2183–2190. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200210000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hakim TS, Michel RP, Chang HK. Effect of lung inflation on pulmonary vascular resistance by arterial and venous occlusion. J Appl Physiol Respir Environ Exerc Physiol. 1982;53(5):1110–1115. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1982.53.5.1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Spinella PC. Warm fresh whole blood transfusion for severe hemorrhage: U.S. military and potential civilian applications. Critical care medicine. 2008;36(7 Suppl):S340–345. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31817e2ef9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]