Abstract

Homologous to E6AP C-terminal (HECT) ubiquitin (Ub) ligases (E3s) are a large class of enzymes that bind to their substrates and catalyze ubiquitination through the formation of a Ub thioester intermediate. The mechanisms by which these E3s assemble polyubiquitin chains on their substrates remain poorly defined. We report here that the Nedd4 family HECT E3, WWP1, assembles substrate-linked Ub chains containing Lys-63, Lys-48, and Lys-11 linkages (Lys-63 > Lys-48 > Lys-11). Our results demonstrate that WWP1 catalyzes the formation of Ub chains through a sequential addition mechanism, in which Ub monomers are transferred in a successive fashion to the substrate, and that ubiquitination by WWP1 requires the presence of a low-affinity, noncovalent Ub-binding site within the HECT domain. Unexpectedly, we find that the formation of Ub chains by WWP1 occurs in two distinct phases. In the first phase, chains are synthesized in a unidirectional manner and are linked exclusively through Lys-63 of Ub. In the second phase, chains are elongated in a multidirectional fashion characterized by the formation of mixed Ub linkages and branched structures. Our results provide new insight into the mechanism of Ub chain formation employed by Nedd4 family HECT E3s and suggest a framework for understanding how this family of E3s generates Ub signals that function in proteasome-independent and proteasome-dependent pathways.

Keywords: E3 ubiquitin ligase, polyubiquitin chain, protein degradation, ubiquitin, ubiquitylation (ubiquitination), HECT

Introduction

Modification of proteins with Ub4 is a critical regulatory mechanism that controls a variety of signaling pathways and processes in eukaryotes. Ub can be conjugated to proteins in a singular form, a process known as monoubiquitination, or in the form of a polyubiquitin chain, which is synthesized by the covalent linkage of multiple Ub monomers to each other. Ub chains can be formed through each of the seven lysine residues of Ub or via the N terminus of Ub, and these chains can be linked in either a homogeneous fashion through one specific lysine of Ub or in a heterogeneous manner through multiple lysines of Ub. In addition, Ub chains have the capacity to form branched structures, in which a single Ub within the chain is linked to two or more Ub subunits through different lysines. The ability of Ub to regulate protein function and characteristics in numerous ways is due, at least in part, to the large number of potential structures that can arise from the ordered assembly of individual Ub monomers into polyubiquitin chains (1–3).

Ub is conjugated to other proteins by a series of E1-E2-E3 enzymes that function to activate, transfer, and ultimately ligate Ub to acceptor sites (most frequently lysines) within a substrate. E3 ligases are crucial regulatory enzymes in this cascade because they are responsible for catalyzing the final transfer of Ub to the substrate. Eukaryotic E3s can be categorized into three major classes based on the presence of a conserved catalytic domain and the mechanism by which they transfer Ub to substrates. The really interesting new gene (RING) and the structurally related U-box family of E3s catalyze the direct transfer of Ub from an E2 enzyme to the substrate by binding to both the E2∼Ub (∼ denotes a thioester linkage) and the substrate simultaneously (4–6). In contrast, the HECT and RING-between-RING families of E3s employ a two-step mechanism to ubiquitinate substrates, in which Ub is first transferred from the E2 to an active-site cysteine within the E3 (resulting in the formation of an E3∼Ub intermediate) and then from the E3 to the substrate (6–9). The HECT family of E3s, of which there are 28 in humans (7), is defined by the presence of a conserved ∼350 amino acid HECT domain located at the extreme C terminus of the protein and has been implicated as key players in an array of biological processes. The Nedd4 family of HECT E3s, which includes WWP1 and eight other human members, is involved in the regulation of transcription, protein trafficking, TGFβ signaling, neuronal development, viral budding, and the immune response (10–13).

Although our understanding of how monomeric Ub is transferred from an E2 to a HECT E3 and from a HECT E3 to substrate has been advanced by several recent studies (14–17), the mechanisms by which these E3s assemble polyubiquitin chains on substrates remain poorly understood. Various models for Ub chain synthesis by a HECT E3 have been proposed (16–22). In the sequential addition model, Ub subunits are transferred one by one from the active-site cysteine of the HECT E3 to the distal Ub on the end of the growing chain, which would be anchored to a substrate lysine residue via an isopeptide bond. In contrast, the en bloc transfer or “indexation” model postulates that the chain is preformed on the active-site cysteine of the HECT E3 and then transferred to the substrate in a single-step reaction. This mechanism of chain synthesis could involve the successive transfer of Ub monomers from E2∼Ub to the HECT E3 active site, although other variations of this model have been envisioned (17, 19, 23). Although it has been proposed that yeast Rsp5 and mammalian Nedd4 are likely to assemble Ub chains through a sequential addition mechanism (16, 20, 21), definitive evidence in support of this model is lacking. In addition, several reports suggest that E6AP assembles free Ub chains via an en bloc transfer mechanism (17, 19, 22), but the general relevance of this mechanism in the context of E6AP substrate polyubiquitination is unclear. Our limited understanding of how HECT E3s catalyze the formation of substrate-linked Ub chains is further highlighted by the presence of a functionally important but poorly defined noncovalent Ub-binding site within the HECT domains of multiple Nedd4 family E3s (21, 24–27).

Regardless of the mechanism by which HECT E3s assemble Ub chains, it is clear that different HECT E3s synthesize polyubiquitin chains with distinct linkage specificities. For example, E6AP has been reported to synthesize chains linked exclusively through Lys-48 of Ub (19, 20, 28) consistent with the role that E6AP plays in targeting p53 for degradation by the proteasome in human papillomavirus-infected cells (29). The HECT E3 ligases UBE3C and AREL1 assemble Ub chains containing mixed Lys-48/Lys-29 or Lys-33/Lys-11 linkages, respectively (30, 31). In contrast, yeast Rsp5 and mammalian Nedd4 preferentially assemble chains linked through Lys-63 of Ub, both in vitro and in vivo (16, 20, 28, 32, 33). Debate appears to exist regarding the issue of whether or not other Nedd4 family HECT E3s, such as Itch, Smurf1, Smurf2, WWP1, and WWP2, exhibit a similar selectivity for Lys-63-linked chain synthesis, with several reports suggesting that these E3s primarily assemble Lys-63-linked chains in vitro (16, 20, 34) and others demonstrating the presence of additional chain types in vivo, most notably Lys-11, Lys-29, and Lys-48 linkages (35–37). Although Nedd4 family HECT E3s have been reported to target a large number of substrates for Ub-dependent degradation by the proteasome in cells (7, 10, 38), Lys-63-linked chains typically do not act as efficient proteasome-targeting signals in vivo (1, 39, 40), highlighting a gap in our understanding of the mechanisms that underlie Ub chain synthesis by these E3s.

Increasing evidence suggests that Ub signals in cells are likely to be far more diversified and complex than originally envisioned (2, 3). Numerous reports have shown that substrates of the Ub conjugation pathway can be modified with Ub chains containing multiple linkages (1, 41, 42), but it is generally unclear whether these signals consist of homogeneous chains attached to multiple substrate lysines, heterogeneous linkages, branched structures, or a combination thereof. Branched chains have been particularly difficult to study. However, recent groundbreaking work has shown that these structures are assembled by the multisubunit RING E3, APC/C, and that branched chains result in the enhanced degradation of cell cycle regulators during mitosis (43). Additional reports of branched chains have been documented (28, 44–46), but the enzymes responsible for synthesizing these chains and the physiological functions of such structures remain poorly defined. Using an in vitro reconstitution system, we report here that the Nedd4 family HECT E3, WWP1, assembles substrate-linked Ub chains containing Lys-63, Lys-48, and Lys-11 linkages. Unexpectedly, we find that the formation of Ub chains by WWP1 occurs in two distinct phases, with each individual phase being characterized by a unique Ub chain topology and linkage specificity. Our results suggest a model for understanding how Nedd4 family members synthesize Ub signals that have the capacity to function in proteasome-independent and proteasome-dependent pathways.

Results

Identification of E2s that function with WWP1

One requirement for understanding the biochemical activities associated with an E3 is to determine the identity of the relevant E2 or a subset of E2s that is capable of cooperating with the E3 in question. To identify E2s that cooperate with WWP1, we used an in vitro reconstitution system with purified proteins to monitor substrate ubiquitination by WWP1 (Fig. 1A). For our initial experiments, we focused on KLF5, a transcription factor that has previously been shown to be targeted for Ub-dependent degradation by WWP1 in vivo (47), as the substrate. A control ubiquitination assay carried out with a fragment of KLF5 lacking the three C-terminal zinc fingers of the protein (KLF51–350) demonstrated that this substrate was polyubiquitinated by WWP1 in vitro on multiple lysine residues (Fig. 1B). Using a commercially available kit containing most of the ∼35 human E2s (48), we screened the ability of each individual E2 to cooperate with WWP1 by testing for the ubiquitination of KLF51–350. The results of our screen indicated that seven different E2s were capable of cooperating with WWP1 to catalyze KLF51–350 polyubiquitination, whereas several of the other E2s tested appeared to support the ability of WWP1 to transfer monoubiquitin to KLF51–350 with a low level of efficiency (Fig. 1C). Similar results were obtained when WBP2, a transcriptional coactivator that has been shown to be ubiquitinated by multiple Nedd4 family E3s in vitro and in vivo (20, 49, 50), was used as the substrate (data not shown).

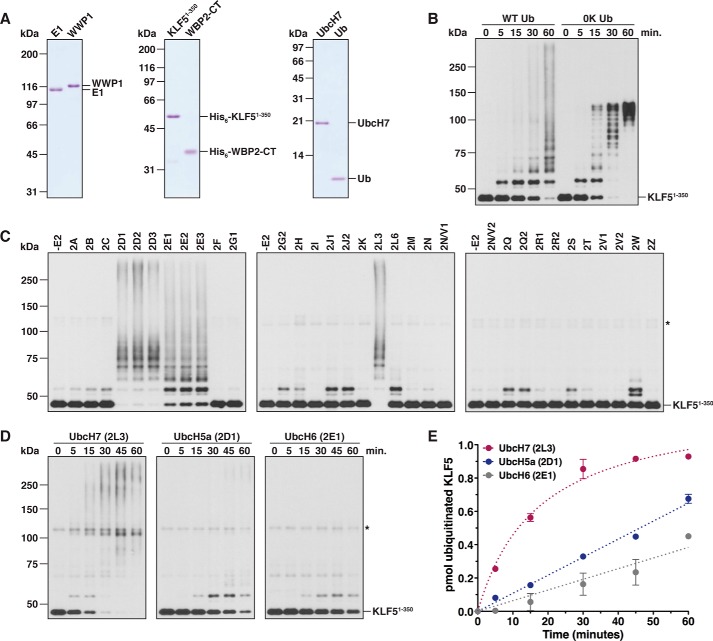

Figure 1.

Identification of E2s that cooperate with WWP1. A, Coomassie-stained gels showing purified protein preparations used for ubiquitination assays with WWP1. The KLF51–350 and WBP2-CT substrates were His6-tagged. All other constructs were untagged full-length proteins. B, time-course ubiquitination assay carried out with E1, UbcH7, WWP1, Ub, and His6-KLF51–350. Reactions were carried out in the presence of wild-type Ub (WT Ub) or a lysine-less Ub mutant (0K Ub). Detection was by anti-His6 immunoblotting. C, ubiquitination of KLF51–350 was assayed as described in B in the presence of the indicated E2 and wild-type Ub. Reactions were carried out for 3 h at 37 °C. The asterisk represents a cross-reacting band corresponding to WWP1. D, KLF51–350 ubiquitination assays were conducted as described above in the presence of UbcH7, UbcH5a, or UbcH6. E, results of two independent experiments conducted as shown in D were quantified by measuring the disappearance of unmodified KLF51–350 via densitometry. The rate of KLF51–350 ubiquitination, calculated from initial data points in the linear phase of the reaction, was 38.9 ± 1.9 fmol/min for UbcH7, 10.8 ± 0.2 fmol/min for UbcH5a, and 6.4 ± 0.5 fmol/min for UbcH6. Error bars represent S.D. of the mean.

We next set out to determine whether WWP1 prefers to cooperate with one or more of the E2s identified in our screen using a more extensive time course ubiquitination assay with KLF51–350 as the substrate. For this analysis, we chose one representative E2 from each subfamily of E2s that was identified as being active with WWP1 in our screen. The results indicated that KLF51–350 was converted to ubiquitinated forms with almost 100% efficiency in the presence of UbcH7 after 30 min of reaction, whereas KLF51–350 was converted to ubiquitinated forms with a reduced efficiency in the presence of UbcH5a or UbcH6 (Fig. 1D). Quantification of initial rate data showed that the rate of ubiquitination was ∼3.5-fold higher in the presence of UbcH7 compared with UbcH5a and ∼6-fold higher in the presence of UbcH7 compared with UbcH6 (Fig. 1E). These results are consistent with a previously published report demonstrating that UBC-18, the orthologue of UbcH7 in worms, is the major E2 for WWP1 in Caenorhabditis elegans (51). Because several studies have shown that the identity of the cooperating E2 does not affect the linkage specificity of Ub chains assembled by a HECT E3 (20, 34, 52), we used UbcH7 as the E2 for all subsequent ubiquitination assays.

Linkage specificity of Ub chains assembled by WWP1

Previous studies have shown that Nedd4 family HECT E3s synthesize polyubiquitin chains linked primarily through Lys-63 of Ub in vitro. However, conflicting results with regard to linkage specificity have been reported for WWP1 (53, 54). To assess the linkage specificity of Ub chains assembled by WWP1, we established an assay to monitor the formation of a free diubiquitin chain by WWP1 in the absence of a substrate. Control time-course assays carried out in the absence and presence of recombinant full-length WWP1 or the WWP1 HECT domain demonstrated that diubiquitin chain synthesis was strictly dependent on the addition of WWP1 to the reaction (Fig. 2A). The chain synthesis activity of the isolated WWP1 HECT domain was more robust than that of full-length WWP1 because higher concentrations of E2 and E3 were required to effectively detect the formation of diubiquitin by full-length WWP1. We next used this assay in conjunction with a series of lysine to arginine Ub mutants that block chain synthesis through one specific lysine of Ub. The K63R mutation completely abolished the chain synthesis activity of the WWP1 HECT domain in this assay, whereas the other lysine to arginine Ub mutations tested had little to no effect (Fig. 2B). Thus, the WWP1 HECT domain has an intrinsic preference for assembling chains linked through Lys-63 of Ub, at least in the context of free Ub chain synthesis.

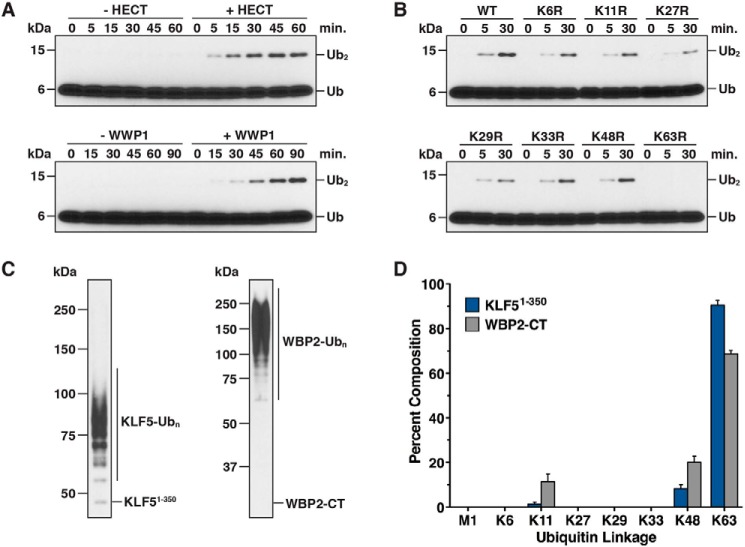

Figure 2.

Linkage specificity of Ub chains synthesized by WWP1. A, diubiquitin chain synthesis assays were conducted in the absence or presence of the WWP1 HECT domain (top panel) and in the absence or presence of full-length WWP1 (bottom panel). Reactions were quenched at the indicated times and resolved by Tris-Tricine SDS-PAGE, and the reaction products were analyzed by anti-ubiquitin immunoblotting. 2-fold higher concentrations of UbcH7 and WWP1 were required for robust detection of diubiquitin by full-length WWP1. B, diubiquitin chain synthesis assays were carried out with the WWP1 HECT domain as described in A, except the indicated lysine to arginine Ub mutant was substituted into the reaction. C, anti-His6 western blots showing the starting material used for quantification of Ub chain linkages by mass spectrometry. Ubiquitinated KLF51–350 and WBP2-CT substrates were purified from all other reaction components under denaturing conditions. D, quantification of Ub chain linkages synthesized by WWP1 using the ubiquitinated material shown in C. Lys-63, Lys-48, and Lys-11 linkages were the only linkages detected (see “Experimental procedures” for details). Data are represented as a percentage of the sum of all linkages detected. Error bars represent triplicate measurements (± S.D. of the mean).

To assess the linkage specificity of Ub chains assembled by full-length WWP1 on substrates, we used a mass spectrometry-based approach with KLF51–350 and WBP2-CT (C-terminal fragment of WBP2; see Fig. 4A) as the substrates. His6-tagged KLF51–350 and WBP2-CT fragments were ubiquitinated with WWP1 in vitro, the ubiquitinated substrates were purified under denaturing conditions to remove >95% of all other reaction components, and the ubiquitinated material was digested with trypsin and analyzed by liquid-chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). Our results showed that WWP1 preferentially assembles Lys-63-linked chains on both substrates, consistent with the results of the diubiquitin chain synthesis assays, but that WWP1 can also extend chains linked through Lys-48 and Lys-11 of Ub with a reduced efficiency (Fig. 2, C and D). Intriguingly, the abundance of Lys-48- and Lys-11-linked chains detected was higher for WBP2-CT than it was for KLF51–350 (∼30% of total linkages for WBP2-CT versus ∼10% for KLF51–350), suggesting that either substrate-specific properties or perhaps the length of Ub chains assembled on these substrates might account for this difference. It will be demonstrated below that this difference is due to the length of the Ub chains that were analyzed and is not likely to reflect an inherent substrate-dependent change in the linkage specificity of chains assembled by WWP1.

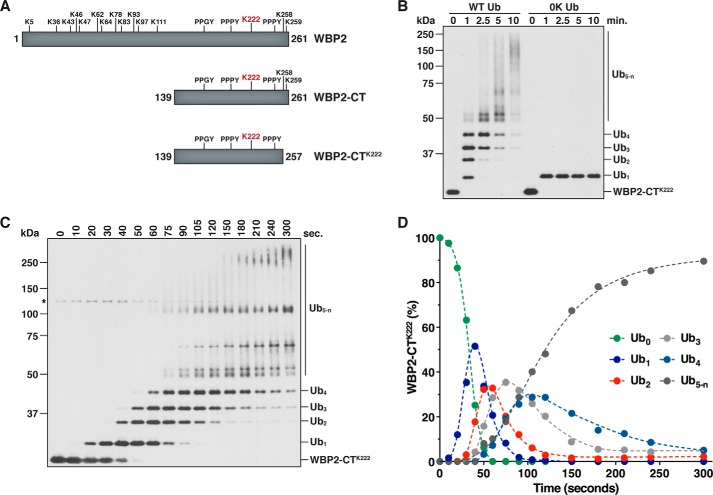

Figure 4.

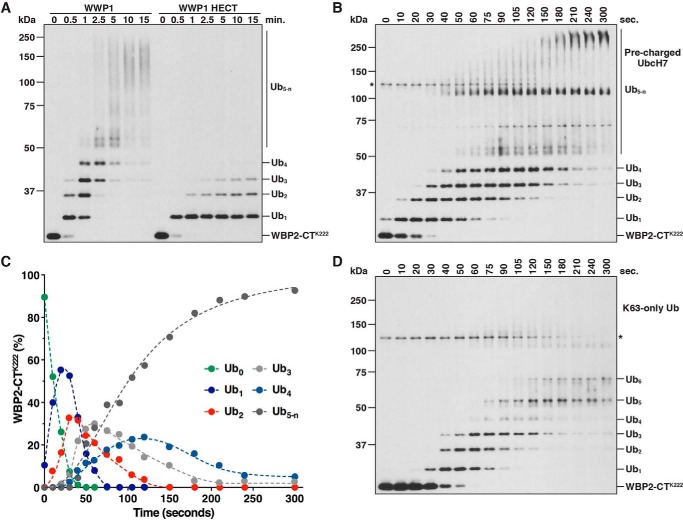

WWP1 assembles Ub chains on WBP2-CTK222 via a sequential addition mechanism. A, schematic of full-length WBP2, WBP2-CT (C-terminal fragment of WBP2), and the WBP2-CTK222 single-lysine substrate. The position of each lysine and PY motif is indicated. Lys-222 is highlighted in red. B, ubiquitination of WBP2-CTK222 was assayed in the presence of wild-type Ub (WT Ub) or a lysine-less Ub mutant (0K Ub) to confirm modification on a single site. Reactions were quenched at the indicated times, and the reaction products were purified under denaturing conditions prior to SDS-PAGE. Detection was by anti-T7 immunoblotting. C, time-course ubiquitination assay carried out with WBP2-CTK222 and full-length WWP1 in the presence of wild-type Ub to evaluate the mechanism of Ub chain synthesis. The reaction was quenched directly in sample buffer at the indicated times, and the reaction products were analyzed by anti-T7 immunoblotting. The asterisk denotes a cross-reacting band corresponding to WWP1. D, quantification of the results shown in C. Band intensities were quantified by infrared fluorescent scanning on the Odyssey imager (LI-COR). Data points represent the percentage of each WBP2-CTK222 species present in the reaction at each time point.

To further explore the linkage preference of WWP1 in the context of substrate ubiquitination, we tested the ability of WWP1 to polyubiquitinate KLF51–350 and WBP2-CT in the presence of the lysine to arginine Ub mutants. A preliminary assay carried out with WBP2-CT as the substrate demonstrated that, like KLF51–350, WBP2-CT was robustly polyubiquitinated by WWP1 in vitro (Fig. 3A). Analysis of the ubiquitination products from reactions carried out with KLF51–350 and WBP2-CT showed that the K63R mutation resulted in the most apparent defect in chain synthesis on both substrates (Fig. 3, B and C). However, the pattern of conjugates observed with the K63R Ub mutant indicated that WWP1 has the ability to synthesize chains linked through other lysines of Ub. Consistent with this observation, a time-course assay showed that the K63R Ub mutant was capable of being incorporated into high molecular weight Ub chains, presumably due to increased usage of Lys-48 and Lys-11 of Ub in the absence of Lys-63 (Fig. 3D). However, the length of these chains was shorter at each time point, and the K63R Ub mutant failed to support the formation of the longest chains observed with wild-type Ub and the K48R Ub mutant (Fig. 3, D and E). Together, these results are consistent with the data from our mass spectrometry analysis and indicate that WWP1 preferentially, although not exclusively, synthesizes chains linked through Lys-63 of Ub.

Figure 3.

Linkage analysis of Ub chains assembled by WWP1 on substrates. A, WBP2-CT ubiquitination was assayed in the presence of wild-type Ub (WT Ub) or a lysine-less Ub mutant (0K Ub). Reactions were quenched in 8 m urea at the indicated times, and ubiquitinated products were purified under denaturing conditions prior to SDS-PAGE. Detection was by anti-HA immunoblotting. B, ubiquitination of KLF51–350 was assayed as described in Fig. 1, but the reactions were carried out for 60 min in the presence of wild-type Ub or the indicated lysine to arginine Ub mutant. C, WBP2-CT was ubiquitinated by WWP1 in the presence of wild-type Ub or the indicated lysine to arginine Ub mutant. Reactions were carried out for 3 min and quenched directly in sample buffer, and the reaction products were detected by anti-T7 immunoblotting. D, time-course ubiquitination assays were carried out with WBP2-CT as the substrate in the presence of wild-type, K63R, or K48R Ub. Time points were withdrawn at the indicated times and analyzed as described in C. The asterisk represents a cross-reacting band corresponding to WWP1. E, results shown in D were quantified via densitometry by measuring the percentage of Ub chains >125 kDa in mass present in the reaction. The cross-reacting band denoted by the asterisk was used to approximate the position of 125 kDa for quantification purposes. Note that the 15-min time point has been omitted from the quantification.

WWP1 assembles Ub chains through a sequential addition mechanism

Several different mechanisms have been proposed for Ub chain synthesis by a HECT E3. Yet in each case examined thus far, conclusive evidence in support of one specific model or another is lacking (16, 18–22). To unambiguously define the mechanism of Ub chain formation employed by WWP1, we developed an assay to kinetically evaluate the formation of a polyubiquitin chain on a single site in our in vitro system. The substrate for this assay was a C-terminal fragment of WBP2 containing a single lysine residue and three PY motifs (WBP2-CTK222; Fig. 4A). Previous work showed that Lys-222 is a major ubiquitination site in WBP2 (20) and that the PY motifs of WBP2 are required for binding to the WW domains of WWP1 (55). To confirm that our single-lysine substrate was, in fact, ubiquitinated at only one position, we tested for the ubiquitination of WBP2-CTK222 in the presence of wild-type Ub or a lysine-less (0K) Ub mutant that cannot form polyubiquitin chains. WBP2-CTK222 was rapidly polyubiquitinated by WWP1 in the presence of wild-type Ub, but modified at only a single position in the presence of the 0K Ub mutant, validating the design of our assay (Fig. 4B). The WWP1 HECT domain by itself, which lacks the four WW domains, was not capable of assembling chains on WBP2-CTK222 efficiently, indicating that stable association of the E3 and substrate via WW domain-PY motif interactions is required for robust polyubiquitination of WBP2-CTK222 (see Fig. 5A).

Figure 5.

Sequential ubiquitination on WBP2-CTK222 under different reaction conditions. A, ubiquitination of WBP2-CTK222 was assayed in the presence of full-length WWP1 or the WWP1 HECT domain. Time points were quenched in 8 m urea, and the reaction products were purified under denaturing conditions prior to SDS-PAGE. Detection was by anti-T7 immunoblotting. B, time-course ubiquitination assay was carried out with WBP2-CTK222 as described in Fig. 4C, except UbcH7 was first charged with Ub and then added to the preformed WWP1·WBP2-CTK222 complex to initiate the reaction. The asterisk represents a cross-reacting band corresponding to WWP1. C, results shown in B were quantified by infrared fluorescent scanning on the Odyssey imager (LI-COR). Data points were plotted as described in Fig. 4D. D, ubiquitination of WBP2-CTK222 was assayed as described in Fig. 4C, but in the presence of the Lys-63-only Ub mutant. The absence of high molecular weight polyubiquitinated species suggests the presence of branched structures and mixed linkages in chains longer than four subunits. Note that a fraction of the total signal in each lane was lost over time due to aggregation of the Lys-63-only Ub mutant.

We next set out to identify the underlying mechanism of Ub chain synthesis on WBP2-CTK222 by directly measuring the appearance of each polyubiquitinated species that arises during the reaction. The distribution of products observed in Fig. 4B did not reveal the underlying mechanism because at the earliest time point taken up to six distinct ubiquitinated intermediates were detected. Although this pattern of conjugates argues strongly against a simple en bloc transfer mechanism, in which the chain increases by x ubiquitins in length (where x = a constant value), another potential explanation for this distribution of products is that the mechanism of chain synthesis is stochastic, such that the chain increases by y ubiquitins in length (where y = the number of ubiquitins tethered to the active-site cysteine of WWP1 at any given point in time). To more precisely define the mechanism of Ub chain synthesis on WBP2-CTK222, we specifically focused on evaluating the formation of ubiquitinated intermediates that arise during the early phase of the reaction. An extensive time-course assay revealed that the appearance of each new ubiquitinated species occurred in a sequential manner and was preceded by a lag phase that increased proportionately as a function of chain length (Fig. 4, C and D). Importantly, it was evident in our assay that the early reaction intermediates served as templates for the formation of successively longer polyubiquitinated products, consistent with the idea that Ub chains are assembled through multiple interdependent transfer events. These results were reproduced under conditions of E3 excess and under E3-limiting conditions (data not shown). Although we cannot rule out the possibility that a small fraction of Ub chains assembled on WBP2-CTK222 are generated through an en bloc transfer mechanism, these results demonstrate that the major mechanism by which WWP1 assembles chains on WBP2-CTK222 is via sequential addition and argue against hypothetical models in which the chain is first pre-assembled on the active-site cysteine of WWP1 and transferred en bloc to the substrate.

To rule out the possibility that our results could be an artifact of the reaction design, we used an altered reaction scheme to monitor the ubiquitination of WBP2-CTK222 by WWP1. The reaction shown in Fig. 4C was initiated by adding buffer containing ATP. Thus, we initiated a separate reaction in parallel by adding the WWP1·WBP2-CTK222 complex to a mixture containing E1, Ub, ATP, and UbcH7 pre-charged with Ub. Under these conditions, the kinetics of WBP2-CTK222 ubiquitination were so rapid that a detectable reaction occurred within the mixing time (Fig. 5B). Importantly, however, the mechanism of Ub chain synthesis on WBP2-CTK222 was unaffected, since the appearance of each successively longer polyubiquitinated species occurred in a sequential manner, and the distribution of ubiquitinated products over time was nearly identical to that of Fig. 4C (Fig. 5, B and C). To ascertain whether Ub chain synthesis by WWP1 proceeds sequentially through Lys-63 of Ub, as suggested by the data in Figs. 2 and 3, we tested the ability of WWP1 to ubiquitinate WBP2-CTK222 in the presence of a mutant Ub containing Lys-63 as the only lysine available for chain formation. Substitution of a Lys-63-only Ub mutant into the reaction had little to no effect on the kinetics of WBP2-CTK222 ubiquitination in the early phase of the reaction, indicating that chains are assembled sequentially through Lys-63 of Ub (Fig. 5D). Interestingly, we could resolve up to six distinct ubiquitinated intermediates in the presence of the Lys-63-only Ub mutant, and the accumulation of high molecular weight reaction products >75 kDa (corresponding to Ub5-n in Fig. 4C) was effectively abolished. These observations suggest that specificity for Lys-63-linked Ub chain synthesis on WBP2-CTK222 is a function of chain length and that chains are elongated by WWP1 in a manner that consists of mixed linkages once the chain reaches four Ub subunits in length.

The WWP1 HECT domain contains a low-affinity, noncovalent binding site for Ub

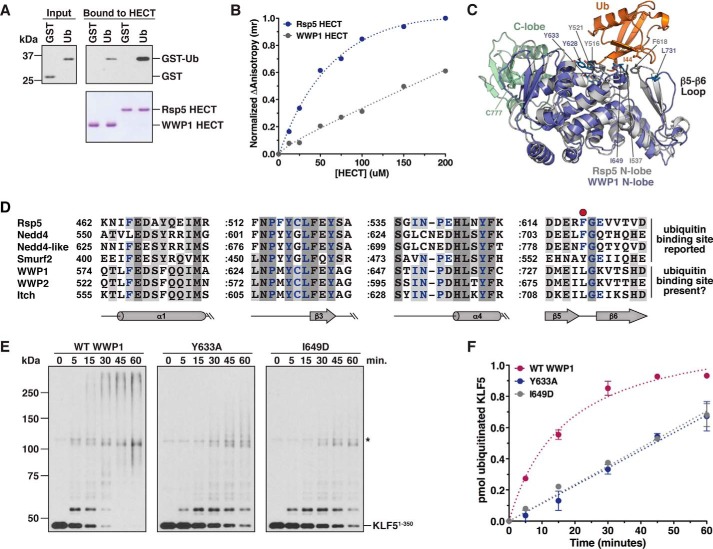

Previous studies have shown that a subset of the Nedd4 family HECT E3s contain a noncovalent Ub-binding site located in the N-terminal lobe of the HECT domain (21, 24–27). The precise mechanism by which this noncovalent site regulates HECT E3 catalysis is not completely understood, although recent work suggests a role for this site in allosterically activating the HECT domain through multiple mechanisms (27). To determine whether the WWP1 HECT domain contains such a site, we tested the ability of the WWP1 HECT domain to bind to a GST-Ub fusion protein using a pulldown assay. In this assay, GST-Ub bound weakly to the WWP1 HECT domain, whereas the Rsp5 HECT domain, which has previously been shown to contain this site (24, 26), bound robustly to GST-Ub (Fig. 6A), as expected. To corroborate this result, we used a fluorescence anisotropy assay to measure binding of the WWP1 and Rsp5 HECT domains to fluorescein-labeled Ub over a series of HECT domain concentrations. For the Rsp5 HECT domain, we observed a concentration-dependent and saturable response, and the estimated Kd value for the Rsp5 HECT-Ub interaction was ∼70 μm (Fig. 6B), in good agreement with published results (26). In contrast, we observed a severely reduced response for the WWP1 HECT domain, and the binding did not approach saturation even at a concentration of 200 μm HECT domain (Fig. 6B). The results of these experiments suggest the presence of a low-affinity, noncovalent Ub-binding site within the WWP1 HECT domain.

Figure 6.

The WWP1 HECT domain contains a low-affinity, noncovalent Ub-binding site. A, binding of GST-Ub to the WWP1 and Rsp5 HECT domains was assayed by incubating immobilized His6-tagged HECT domains with an E. coli lysate containing GST-Ub or GST alone. Input and bound proteins (top panels) were detected by anti-GST immunoblotting. HECT domains were visualized by Coomassie staining (bottom panel). B, fluorescence anisotropy assay was performed with fluorescein-labeled ubiquitin and increasing concentrations of the WWP1 or Rsp5 HECT domains. Normalized anisotropy is plotted as a function of HECT domain concentration. The Kd value for the Rsp5 HECT-Ub interaction was determined to be 70.3 ± 8.9 μm. It was not possible to determine the Kd value for the WWP1 HECT-Ub interaction from this experiment. C, structural alignment of the WWP1 HECT domain N-lobe (PDB 1ND7) with the Ub-binding Rsp5 N-lobe (PDB 3OLM). The root-mean-square deviation was 2.9 Å over 240 Cα. Residues present at the interface between the Rsp5 N-lobe and Ub are shown. D, sequence alignment of the HECT domain N-lobes from yeast Rsp5 and human Nedd4 family members (constructed in Clustal Omega). Residues highlighted in purple make direct contacts with Ub in the structure of Rsp5 HECT·Ub (PDB 3OLM). The conserved Phe present in three of the four Ub-binding N-lobes (red circle) is absent in WWP1, WWP2, and Itch. A colon is used to represent a gap in sequences that are not part of the Ub-binding site. E, ubiquitination of KLF51–350 was assayed as described in Fig. 1, except the indicated WWP1 protein (wild-type or mutant) was added to the reaction. F, results of two independent experiments conducted as shown in E were quantified as described in Fig. 1E. The rate of KLF51–350 ubiquitination was 38.8 ± 1.9 fmol/min for wild-type WWP1, 11.3 ± 0.4 fmol/min for the Y633A mutant, and 11.8 ± 0.3 fmol/min for the I649D mutant. Error bars represent S.D. of the mean.

To ascertain whether a structural basis exists for the finding that the WWP1 HECT domain binds to Ub with a reduced affinity, we overlaid the WWP1 HECT domain N-lobe onto the crystal structure of the Rsp5 HECT domain in complex with Ub (26). Our alignment showed that the WWP1 and Rsp5 N-lobes were virtually superimposable, and most of the residues involved in Ub binding in the Rsp5 N-lobe were highly conserved in WWP1 (Fig. 6C). However, one key difference that exists is within a Ub-binding hairpin loop (corresponding to β5-β6 in the Rsp5 N-lobe) containing a crucial phenylalanine residue, Phe-618, that packs up against the Ile-44 hydrophobic patch of Ub. This phenylalanine is a leucine in WWP1, and the overall sequence and structure of this loop in WWP1 is not conserved (Fig. 6, C and D). Furthermore, an overlay of the WWP1 N-lobe with the Ub-binding Nedd4 N-lobe revealed a similar divergence of the β5-β6 hairpin loop (data not shown). These observations suggest that alteration of this loop in WWP1 and the replacement of Phe-618/Phe-707 in Rsp5/Nedd4 with Leu-731 in WWP1 may explain why the WWP1 HECT domain binds to Ub with a lower affinity than the Rsp5 and Nedd4 HECT domains (21, 26).

To determine if the WWP1 HECT domain noncovalent Ub-binding site regulates the catalytic activity of WWP1, as reported for other Nedd4 family HECT E3s (21, 24–27), we tested the effect of point mutations that are predicted to disrupt this site on the ability of WWP1 to ubiquitinate KLF51–350. Based on our alignments with Rsp5 and other Nedd4 family HECT domains (Fig. 6, C and D), in addition to previous work (24, 26), we made two mutations, Y633A and I649D, that would be expected to eliminate Ub binding and severely inhibit substrate ubiquitination if an analogous site were present in WWP1. Both of the mutations tested impaired the formation of Ub conjugates on KLF51–350, with each mutation resulting in an ∼3.5-fold decrease in the rate of KLF51–350 ubiquitination (Fig. 6, E and F). We conclude that the WWP1 HECT domain Ub-binding site, despite its lower Ub-binding affinity, is important for regulating the catalytic activity of WWP1. Although we have not further investigated the mechanistic role of this site in WWP1, we note that these results are consistent with a recent study demonstrating that enhanced Ub binding to the WWP1 N-lobe activates WWP1 through multiple mechanisms (27).

Length-dependent change in specificity for Lys-63-linked Ub chain synthesis

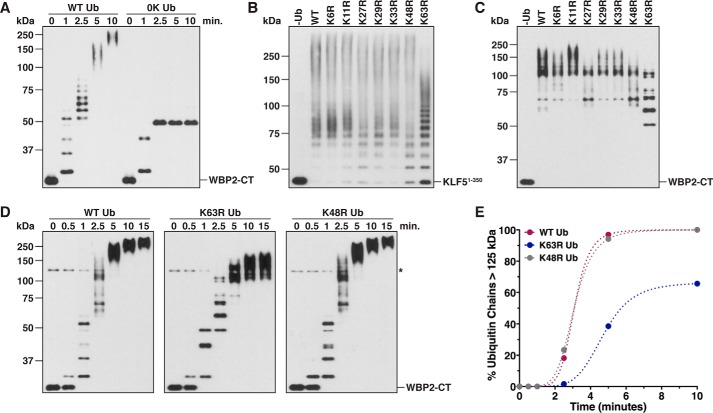

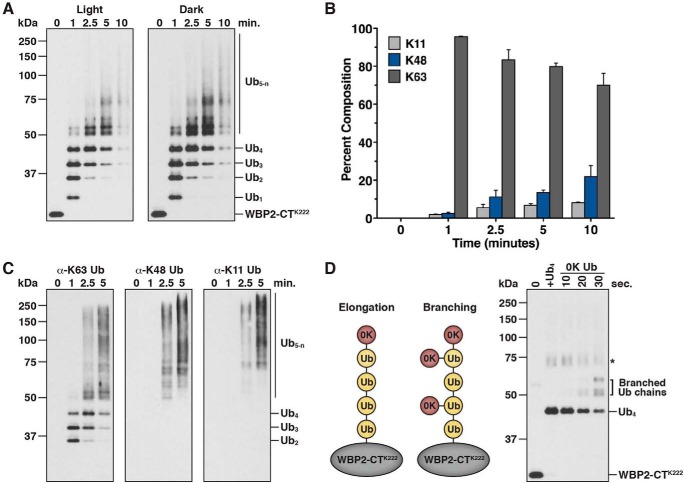

The results of our ubiquitination assays with WBP2-CTK222 suggested that specificity for Lys-63-linked Ub chain synthesis by WWP1 is altered as chain length increases (Figs. 4C and 5D). To further explore this idea, we performed a time-course experiment in which the abundance of Lys-63, Lys-48, and Lys-11 linkages incorporated into Ub chains assembled on WBP2-CTK222 was quantified by mass spectrometry. Reaction products were quenched in 8 m urea at the indicated times, WBP2-CTK222 species were purified under denaturing conditions, and chain linkages were analyzed by LC-MS/MS. The results of this analysis clearly demonstrated that specificity for Lys-63-linked Ub chain synthesis by WWP1 was reduced as chain length increased (Fig. 7, A and B). At the 1-min time point, >95% of Ub chains analyzed were Lys-63-linked, whereas at the 10-min time point, ∼70% of Ub chains analyzed were Lys-63-linked and ∼30% of chains were linked through Lys-48 or Lys-11 of Ub. These differences are consistent with the results of our linkage analysis with KLF51–350 and WBP2-CT (Fig. 2, C and D), which suggested that the length of the Ub chains analyzed might affect the linkage specificity of chains detected. Notably, these results underestimate the magnitude of Lys-48- and Lys-11-linked chains assembled at later time points because our assay measures the sum of all linkages present in high molecular Ub chains, which are formed using a homogeneous Lys-63-linked chain as the template.

Figure 7.

Specificity for Lys-63-linked Ub chain synthesis by WWP1 is a function of chain length. A, anti-T7 western blots showing the starting material used for quantification of Ub chain linkages formed on WBP2-CTK222 over time by mass spectrometry. The reaction was quenched in 8 m urea at the indicated times, and the ubiquitinated products were purified under denaturing conditions prior to SDS-PAGE. B, quantification of Ub chain linkages using the ubiquitinated material shown in A. Results are represented as a percentage of the sum of all linkages detected. Error bars represent triplicate measurements (±S.D. of the mean). C, ubiquitination of WBP2-CTK222 was assayed in the presence of wild-type Ub as described in Fig. 4B. The reaction products were probed with linkage-specific antibodies to detect Lys-63-, Lys-48-, and Lys-11-linked chains. D, ubiquitination of WBP2-CTK222 was assayed in two rounds of reaction to detect a branching activity by WWP1. WBP2-CTK222 was first modified with a Lys-63-linked Ub4 chain, such that the substrate was fully converted to its tetraubiquitinated form (lane 2). A molar excess of a lysine-less Ub (0K Ub) was then added to the reaction. The reaction products were quenched at the indicated times as described in A and detected by anti-T7 immunoblotting. The asterisk denotes a cross-reacting species that originates from an aggregate present in the Lys-63-linked Ub4 preparation.

To confirm our mass spectrometry results and gain further insight into this length-dependent change in specificity for Lys-63 linkages, we evaluated ubiquitinated WBP2-CTK222 reaction products by immunoblotting with linkage-specific antibodies. As expected, the Lys-63 linkage-specific antibody recognized a wide range of reaction products, including di-, tri-, and tetraubiquitinated WBP2-CTK222, indicating that all polyubiquitinated products formed contain Lys-63 linkages (Fig. 7C). In contrast, the Lys-48 and Lys-11 linkage-specific antibodies exclusively recognized high molecular weight conjugates designated Ub5-n, indicating that Lys-48 and Lys-11 linkages are present only in chains longer than four Ub subunits. These results are consistent with the data from our mass spectrometry analysis. We conclude that WWP1 assembles a tetraubiquitin chain on WBP2-CTK222 linked homogeneously through Lys-63 of Ub and that once the chain reaches four Ub subunits in length, chains are elongated by WWP1 in a manner that consists of Lys-48 and Lys-11 linkages, in addition to Lys-63 linkages. Because our assay monitors the formation of a polyubiquitin chain on a single acceptor site, these results imply that WWP1 synthesizes branched Ub chains containing mixed linkages once the chain reaches four Ub subunits in length.

We next directly tested the idea that WWP1 synthesizes branched Ub chains on WBP2-CTK222 once the chain reaches four Ub subunits in length using an assay designed to bypass the initial steps of chain initiation and elongation. WBP2-CTK222 was first modified with a Lys-63-linked tetraubiquitin chain in a brief incubation with WWP1, such that the substrate was fully converted to its tetraubiquitinated form (Fig. 7D, lane 2). A 0K Ub mutant was then added to the reaction in excess, and time points were withdrawn and analyzed to determine how many sites within the Lys-63-linked tetraubiquitin chain were capable of acting as acceptors for 0K Ub. We reasoned that if chain elongation by WWP1 proceeded exclusively off of the distal Ub on the end of the growing chain, then 0K Ub should be conjugated to only a single site within the Lys-63-linked chain. However, if chain assembly occurred in a manner that included the formation of branched structures, then 0K Ub should be conjugated to multiple sites within the Lys-63-linked chain. Strikingly, 0K Ub was conjugated to three different sites within the Lys-63-linked chain (Fig. 7D), and the pattern of conjugates closely resembled that which was observed in reactions carried out with wild-type Ub (compare Fig. 7, D to A). These results provide direct evidence for a branching activity by WWP1 and demonstrate that WWP1 is capable of extending Ub chains of complex topology and multiple linkages off of a homogeneous Lys-63-linked tetraubiquitin chain.

Discussion

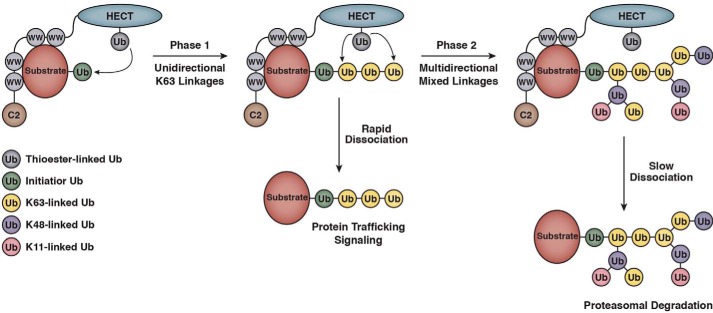

The mechanisms by which HECT E3s assemble Ub chains on substrates remain incompletely understood, despite the availability of several crystal structures of HECT domains in complex with E2∼Ub, substrate, or Ub (14–16, 21, 26). Our results suggest a two-phase model for the synthesis of substrate-linked Ub chains by WWP1 that may account for several puzzling observations previously reported for WWP1 and other Nedd4 family E3s (Fig. 8). In the first phase of Ub chain synthesis, Ub monomers are transferred in a sequential fashion from the active-site cysteine of WWP1 to the distal Ub on the end of the growing chain. Chain assembly in this phase occurs in a unidirectional manner and proceeds exclusively through Lys-63 of Ub, resulting in the formation of a Lys-63-linked tetraubiquitin chain on the substrate. Once the chain reaches four Ub subunits in length, chains are then elongated by WWP1 in a manner that consists of mixed linkages containing Lys-48- and Lys-11-linked Ub chains, in addition to Lys-63-linked chains. This second phase of chain synthesis is multidirectional and appears to progress in a manner that is characterized, at least in part, by the formation of branched structures. As discussed in more detail below, our model suggests a framework for understanding how the catalytic activities of WWP1 and other Nedd4 family members are coordinated to enable the formation of Ub signals that function in proteasome-independent and proteasome-dependent pathways.

Figure 8.

Two-phase model for substrate-linked Ub chain synthesis by WWP1. Once the initiator Ub has been conjugated to the substrate, the formation of Ub chains by WWP1 occurs in two distinct phases. In phase 1, Ub monomers are transferred from the active-site cysteine of WWP1 to the distal Ub on the end of the growing chain. This phase of Ub chain synthesis is unidirectional and occurs with strict specificity for Lys-63 linkages. In phase 2, Ub chain assembly proceeds in a manner that consists of mixed Lys-48, Lys-11, and Lys-63 Ub linkages and is characterized by formation of branched structures. Ub chain synthesis in this phase is multidirectional, resulting in an increase in the density of Ub subunits surrounding the substrate. Substrates that dissociate from the E3 rapidly and therefore do no enter phase 2 are modified with monoubiquitin or short Lys-63-linked chains (2–4 subunits), which typically mark proteins for non-proteasomal pathways. Substrates that remain more stably associated with the E3 and therefore enter into phase 2 have the potential to be modified with larger, more complex Ub chains containing mixed linkages, which are likely to serve as efficient proteasome targeting signals in vivo.

The first phase of Ub chain synthesis by WWP1 involves the unidirectional formation of a tetraubiquitin chain linked through Lys-63 of Ub. As demonstrated by mass spectrometry and the detection of reaction products with linkage-specific antibodies, Ub chain formation in this phase occurs with a very high degree of specificity for Lys-63 linkages. This result by itself is not surprising because most, if not all, Nedd4 family E3s tested have been shown to preferentially assemble Lys-63-linked chains in vitro (16, 20, 28, 34, 56). A key finding from our kinetic analysis of WBP2-CTK222 ubiquitination is that we could conclusively show, in the early phase of the reaction, that Ub chains are assembled by WWP1 through a sequential addition mechanism, in which Ub monomers are transferred to the substrate in a successive fashion. Although it has been suggested in previous studies that Rsp5 and Nedd4 are likely to assemble Ub chains through a sequential addition mechanism (16, 20, 21), our results differ from those in prior studies because we could kinetically resolve all of the relevant intermediates that one would predict to observe in a sequential addition model (Fig. 4, C and D). Notably, our results bear strong resemblance to the mechanism of Ub chain formation employed by the budding yeast SCFCdc4 and human SCFβ-TrCP multisubunit RING E3s, suggesting that RING and HECT E3s share a common mechanism of Ub chain assembly (57). As expected, ubiquitination by WWP1 required the presence of a noncovalent Ub-binding site within the HECT domain (21, 25, 26). Interestingly, a recent study proposed that this site regulates the activity of WWP1 and other Nedd4 family E3s through multiple mechanisms that include, but are not limited to, Ub chain formation (27).

In the second phase of Ub chain synthesis, chains are elongated by WWP1 in a multidirectional fashion that consists of mixed Ub linkages. Once the growing chain reaches four Ub subunits in length, a distinctive shift in the linkage specificity of chains assembled by WWP1 was observed. The presence of Lys-48- and Lys-11-linked chains in reaction products of >4 Ub subunits in length was detected by mass spectrometry and confirmed using linkage-specific antibodies. Two findings support the idea that at least a fraction of these high molecular weight species are composed of branched chains. First, since our substrate contains a single acceptor site, there is no obvious reason why the electrophoretic mobility of chains resolved by SDS-PAGE would deviate from the stepwise pattern observed for Ub1–Ub4 if chains >4 Ub subunits were elongated by WWP1 in a unidirectional fashion. Substitution of a Lys-63-only Ub mutant into the reaction clearly demonstrated that chains >4 subunits in length could be individually resolved in the absence of other lysines on Ub that have the potential to serve as branch points. Second, we have directly demonstrated a branching activity for WWP1 using an assay that was designed to test the ability of WWP1 to nucleate the formation of a chain off of Ub subunits within a Lys-63-linked tetraubiquitin chain anchored to a substrate (Fig. 7D). Interestingly, we were unable to detect a branching activity for WWP1 when the substrate was a free Lys-63-linked tetraubiquitin chain (data not shown), suggesting that the branching activity of WWP1 in the context of substrate polyubiquitination arises from topological constraints placed on the distal Ub at the end of the substrate-anchored chain. We speculate that the length at which WWP1 switches from unidirectional Lys-63-linked chain synthesis to multidirectional branched chain synthesis could vary for different substrates and might depend on the distance between the site of WWP1 binding, the position of the substrate lysine, and the active-site cysteine of WWP1 responsible for positioning the donor Ub during chain assembly.

An important implication of our model is that it suggests a framework for understanding how the biochemical activities and functions of WWP1 and other Nedd4 family HECT E3s are integrated in vivo. Many studies have demonstrated that Nedd4 family members modify a specific subset of their substrates with monoubiquitin or short Lys-63-linked chains (33, 58–62). Yet, additional reports have shown that Nedd4 family E3s have the ability to target numerous substrates for degradation by the proteasome (7, 10, 13, 38), which typically requires the attachment of Lys-48- and/or Lys-11-linked chains to substrates (1, 2, 43, 63). Importantly, our model provides a mechanistic framework to explain how WWP1 and other Nedd4 family members catalyze the formation of Ub signals that are capable of functioning in proteasome-independent and proteasome-dependent pathways (Fig. 8). We propose that the rate of product intermediate dissociation during a single encounter between E3 and substrate determines the exact nature and function of the Ub signal that is appended by this family of E3s. Substrates that dissociate from the E3 rapidly are modified with monoubiquitin or short Lys-63-linked chains and thus are destined for non-proteasomal pathways, whereas substrates that remain more stably associated with the E3 have the potential to be modified with longer, more complex Ub chains containing Lys-48 and Lys-11 linkages, which are likely to act as proteasome targeting signals in vivo (1, 2, 43, 63). Stable association of the substrate with the E3 in vivo may be conferred by other proteins or membranes that form part of a larger E3·substrate complex, post-translational modifications, or a PY motif containing adaptor proteins, of which a large variety has been described for Nedd4 family E3s (64–68).

Is our two-phase model for Ub chain synthesis applicable to other Nedd4 family members? Two proteomic studies in which the linkage specificity of Ub chains assembled by multiple Nedd4 family E3s was surveyed by mass spectrometry suggest that our model is likely to be relevant for other family members. In one study, Lys-63-linked chains were reported to represent ∼90% of the total chain population analyzed for all E3s tested, and in the other study Lys-63-linked chains were found to represent anywhere from 50 to 70% of chains analyzed depending on the Nedd4 family E3 assayed (neither study tested WWP1), with the remaining 30–50% consisting predominantly of Lys-48- and Lys-11-linked chains (16, 34). Both studies assayed Ub chain formation by isolated HECT domains in an autoubiquitination assay, but the key difference between these studies was in the length of the Ub chains that were analyzed. The study that reported a chain type specificity of ∼90% Lys-63 linkages examined a broad range of ubiquitinated products that included species as small as 50 kDa in mass, whereas the study that reported a much higher abundance of Lys-11- and Lys-48-linked chains focused specifically on ubiquitinated products >125 kDa. In light of our finding that specificity for Lys-63-linked Ub chain synthesis by WWP1 is a function of chain length, we find it likely that the results of these studies are explained by a similar length-dependent change in the linkage specificity of Ub chains assembled by other Nedd4 family E3s. We propose that our two-phase model for Ub chain synthesis is generally applicable to other Nedd4 family members and that this mode of catalysis provides a mechanism to ensure that Nedd4 family E3s are capable of synthesizing multiple types of Ub signals with discrete functions in vivo.

Experimental procedures

Reagents and constructs

The antibodies used in this study were as follows: anti-His6 (Sigma, clone HIS-1, catalog no. H1029); anti-T7 (EMD Millipore, catalog no. 69522); anti-HA (clone 12CA5, in-house antibody); anti-Ub (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, clone P4D1, catalog no. sc-8017); anti-GST (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, clone Z-5, catalog no. sc-459); Lys-63-specific anti-Ub (Abcam, clone Apu3, catalog no. ab179434); Lys-48-specific anti-Ub (Abcam, clone Apu2, catalog no. ab140601); and Lys-11-specific anti-Ub (EMD Millipore, clone 2A3/2E6, catalog no. MABS107-I). Insect cell-derived human E1 and bacterially expressed human UbcH7, Ub, and all Ub mutants were purchased from Boston Biochem. His6-KLF51–350 purified from Escherichia coli was obtained from Proteintech. Diubiquitin chain standards for mass spectrometry and Lys-63-linked tetraubiquitin were purchased from Boston Biochem. The E2scan kit (catalog no. 67-0005-001) was obtained from Ubiquigent. Constructs for bacterial expression of human WWP1, WBP2-CT, WBP2-CTK222, and the HECT domains of WWP1 and Rsp5 were subcloned into the pET-28a(+) or pET-30 Xa/LIC vectors (EMD Millipore). Further details on reagents and constructs used in this study are available upon request.

Protein expression and purification

Full-length His6-WWP1 was expressed in the Rosetta-2(DE3) strain of E. coli by induction with 1 mm isopropyl 1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside at 20 °C for 5–6 h. Cell pellets were frozen at −80 °C, thawed, and resuspended in 20 ml of lysis buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, 500 mm NaCl, 10 mm imidazole, 1% Tween 20, 5% glycerol, pH 8.0) containing 1 mm PMSF, and 10 mm β-ME per liter of cell pellet. Cells were lysed by sonication, and the lysate was clarified by centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 30 min at 4 °C. The cleared fraction was then mixed with 500 μl of packed TALON beads (Clontech) per liter of cell pellet and rotated for 1.5 h at 4 °C. The beads were washed once in lysis buffer containing 5 mm β-ME and twice in wash buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, 500 mm NaCl, 20 mm imidazole, 1% Tween 20, 5% glycerol, pH 8.0) containing 5 mm β-ME. Beads were resuspended in 1 ml of thrombin cleavage buffer (20 mm Tris-HCl, 150 mm NaCl, 5% glycerol, pH 8.0), and thrombin cleavage was carried out overnight for 15–20 h at 4 °C with 2 units of biotinylated thrombin (EMD Millipore) to cleave off the His6 tag. Thrombin was then removed with streptavidin-agarose beads (EMD Millipore) according to the manufacturer's instructions. DTT was added at a final concentration of 1 mm, and preparations were concentrated to ∼0.5 mg/ml by ultrafiltration. Proteins were aliquoted and stored at −80 °C. Protein purity and concentration were assessed by Coomassie staining of SDS-polyacrylamide gels and using the A280 method. Enzyme concentrations for all assays were based on total protein content.

The WBP2-CT and WBP2-CTK222 substrates were expressed as His6-tagged proteins in the Rosetta-2(DE3) E. coli strain and isolated on TALON beads, as described above for WWP1, except proteins were eluted from the TALON resin in 1 ml of elution buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, 100 mm NaCl, 250 mm imidazole, 5% glycerol, pH 8.0), resulting in the presence of an intact N-terminal His6 tag. Imidazole was removed by ultrafiltration with repeated rounds of concentration and dilution in storage buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, 100 mm NaCl, 5% glycerol, pH 8.0). Protein aliquots were stored at −80 °C, and protein purity and concentration were assessed as described above. The His6-WWP1 and His6-HECT constructs for diubiquitin chain synthesis assays were expressed in E. coli and purified in the same manner, but the elution and storage buffers contained 2.5 mm β-ME, and the eluted protein preparations were concentrated to ∼0.5 mg/ml prior to storage at −80 °C. For the fluorescence anisotropy assays, the His6-tagged Rsp5 and WWP1 HECT domains were purified, eluted, and concentrated largely as described above, except the preparations were further purified on anion-exchange and size-exclusion columns.

Ubiquitination assays

Substrate ubiquitination assays with WWP1 contained 100 nm E1, 500 nm UbcH7 or the indicated E2, 350 nm WWP1, 350 nm His6-tagged substrate (KLF51–350, WBP2-CT, or WBP2-CTK222), and 50 μm Ub (wild-type or the indicated mutant). Unless otherwise specified, reactions were initiated by the addition of buffer containing ATP (final concentrations were 25 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 50 mm NaCl, 0.1 mm DTT, 5 mm MgCl2, 5 mm ATP), mixed by pipetting, and the zero time point was withdrawn on ice. Reactions were then transferred to a 37 °C water bath. Time points were withdrawn at the indicated times and quenched in 2× SDS-PAGE sample buffer (all assays unless otherwise specified in the figure legends) or denaturing buffer (25 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 50 mm NaCl, 8 m urea). Reaction products quenched in denaturing buffer were subject to a post-assay purification on TALON beads to isolate ubiquitinated substrates and circumvent the nonspecific detection of WWP1. Reaction products were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-His6, anti-T7, anti-HA, or anti-Ub antibodies as indicated in the figure legends.

Quantification of ubiquitination assays with WBP2-CTK222 was performed by fluorescent scanning using the Odyssey infrared imaging system (LI-COR Biosciences). For each lane, individual bands were quantified as a percentage of the total signal present in all bands (57). Background fluorescence resulting from the cross-reacting band (Figs. 4C and 5B) was subtracted out of the analysis. Data points were plotted in GraphPad Prism 5.0 software, and manual curve fitting was used to construct the graphs shown in Figs. 4D and 5C. For ubiquitination assays with KLF51–350 as the substrate, chemiluminescent signal intensities were quantified for unmodified KLF51–350 by densitometry in ImageJ64. Initial rates of KLF51–350ubiquitination were determined using linear regression analysis in Prism 5.0 with initial data points in the linear phase of the reaction. WBP2-CT ubiquitination assays in Fig. 3D were quantified by measuring the amount of Ub chains larger than ∼125 kDa as a percentage of the total signal in each lane in ImageJ64.

Diubiquitin chain synthesis assays

Diubiquitin chain synthesis assays performed with the WWP1 HECT domain contained 100 nm E1, 500 nm UbcH7, 500 nm His6-tagged WWP1 HECT, and ∼115 μm wild-type Ub or the indicated Ub mutant. Assays conducted with full-length WWP1 contained 2-fold higher concentrations of UbcH7 and His6-WWP1 because in preliminary experiments it was determined that the chain synthesis activity of full-length WWP1 was less robust than that of the isolated WWP1 HECT domain. Reactions were initiated by adding buffer containing ATP (final concentrations as indicated above), and time points were withdrawn and quenched in 1× Tris-Tricine SDS-PAGE sample buffer. Reaction products were resolved on 16% Tris-Tricine gels and analyzed by anti-Ub immunoblotting.

Mass spectrometry

Samples for mass spectrometry were prepared by ubiquitinating the KLF51–350, WBP2-CT, and WBP2-CTK222 substrates with full-length WWP1 as described above. Reactions containing 2 μg of His6-tagged substrate were incubated at 37 °C for 60 min (KLF51–350), 10 min (WBP2-CT), or for the indicated times in Fig. 7A (WBP2-CTK222). Reaction products were quenched in denaturing buffer (25 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 50 mm NaCl, 8 m urea), and the ubiquitinated substrates were purified on TALON beads to remove >95% of autoubiquitinated species (estimated by spectral counting) and free Ub chains from the sample. Ubiquitinated material was eluted from the beads in denaturing buffer containing 250 mm imidazole. The imidazole was removed by ultrafiltration, and samples were concentrated to ∼50 μl for mass spectrometry. In preliminary experiments carried out with KLF51–350 and WBP2-CT as the substrates and a mixture of diubiquitin chain standards representing all eight possible chain linkages, Lys-63, Lys-48, and Lys-11 linkages were the only linkages detected. Therefore, a standard sample containing 1 μg each of Lys-63, Lys-48, and Lys-11-linked diubiquitin was prepared in parallel for quantitation purposes.

Samples were digested overnight with trypsin (Promega) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The digests were pressure-loaded onto a 250-μm inner diameter fused silica capillary (Polymicro Technologies) column with a Kasil frit packed with 3 cm of a 5-μm C18 resin (Phenomenex) that was connected to a 100-μm inner diameter fused silica capillary (Polymicro Technologies) analytical column with a 5-μm pulled tip, packed with 10 cm of 5-μm C18 resin. The split column was positioned in-line with an 1100 quaternary HPLC pump (Agilent Technologies), and eluted peptides were electrosprayed directly into an LTQ Orbitrap XL mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The buffer solutions used were as follows: 5% acetonitrile, 0.1% formic acid (buffer A) and 80% acetonitrile, 0.1% formic acid (buffer B). The 180-min elution gradient had the following profile: 0% buffer B until 5 min, up to 40% buffer B at 125 min, up to 60% buffer B at 145 min, up to 100% buffer B at 155 min continuing to 165 min, and finally down to 0% buffer B at 170 min. A cycle consisted of one full scan mass spectrum (400–1600 m/z), followed by five data-dependent collision-induced dissociation MS/MS spectra. Charge state rejection was enabled for unassigned charge states and charge state one. Dynamic exclusion was enabled with a repeat count of one, a repeat duration of 30 s, an exclusion list size of 500, and an exclusion duration of 180 s. Early expiration was enabled with an expiration count of three and an expiration signal-to-noise ratio threshold of three. Application of mass spectrometer scan functions and HPLC solvent gradients were controlled by the Xcalibur data system (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

MS/MS spectra were extracted using RawXtract (version 1.9.9) (69). MS/MS spectra were then searched with the ProLuCID algorithm (70) against a Saccharomyces cerevisiae and E. coli database concatenated to a decoy database in which the sequence for each entry in the original database was reversed (71) and supplemented with UniProt sequences for human UBA1, UBE2L3, WWP1, KLF5, WBP2, and UBB. The ProLuCID search was performed using full enzyme specificity and differential modification of lysine due to ubiquitination remnant (114.042927). ProLuCID search results were then assembled and filtered using the DTASelect algorithm (version 2.0) (72). The protein identification false-positive rate was kept below 1%, and all peptide-spectra matches had less than 10 ppm mass error. Extracted ion chromatograms for fully tryptic peptides containing the remnant of Lys-63, Lys-48, and Lys-11 linkages were generated from Orbitrap full scans. A 0.02 atomic mass unit window was used for peak extraction and area calculation in the XCalibur Qual Browser software (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The relative abundance of Lys-63, Lys-48, and Lys-11 linkages was determined for each of the ubiquitinated substrates and normalized to the data from the standard containing Lys-63, Lys-48, and Lys-11-linked diubiquitin (34).

Ub binding assays

The WWP1 and Rsp5 HECT domains were assayed for binding to Ub using a previously published pulldown experiment (24), with minor modifications. Briefly, the His6-tagged WWP1 and Rsp5 HECT domains were expressed in E. coli and immobilized on TALON beads according to the manufacturer's instructions. Beads containing ∼10 μg of the WWP1 or Rsp5 HECT domain were incubated with an E. coli lysate containing ∼30 μg of GST or GST-Ub for 1 h at 4 °C. Beads were washed twice in binding buffer (PBS, 1% Triton X-100, 5% glycerol, pH 7.5) containing 10 mm imidazole and once in binding buffer containing 20 mm imidazole. Bead-bound proteins were eluted in SDS-PAGE sample buffer and analyzed by anti-GST immunoblotting or Coomassie staining.

Fluorescence anisotropy measurements were made with E. coli-derived His6-tagged HECT domains and fluorescein-labeled Ub modified at the N terminus (Boston Biochem). The HECT domains of Rsp5 and WWP1 were dialyzed into anisotropy buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 250 mm NaCl, 0.5 mm tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine, 2.5% (w/v) sucrose) at 4 °C overnight and concentrated to 12 mg/ml. Protein aggregates were removed by centrifugation at 100,000 rpm for 10 min in a TLA 110 rotor and Optima TLX ultracentrifuge (Beckman Coulter). Fluorescein-labeled Ub was directly resuspended in anisotropy buffer, and free fluorescein was removed by ultrafiltration with repeated rounds of concentration and dilution in anisotropy buffer. 50 nm fluorescein-Ub was combined with various concentrations of Rsp5 or WWP1 HECT domains in anisotropy buffer and incubated at room temperature for 5 min in a volume of 50 μl. Samples were loaded into an opaque 384-well plate (Greiner Bio-One), and anisotropy measurements were made using the Safire II microplate reader (Tecan), with instrument settings as follows: λex = 470 nm; λem = 520 nm; G-factor correction = 1.1114; reads per well = 10. The data were fit to a one-site specific binding model in GraphPad Prism 5.0, and the Kd for the Rsp5 HECT-Ub interaction was determined to be 70.3 ± 8.9 μm. It was not possible to determine a Kd value for the WWP1 HECT-Ub interaction from our data.

Detection of branched Ub chains

To detect the formation of branched chains by WWP1, ubiquitination of WBP2-CTK222 was assayed in two rounds of reaction. In the first round, WBP2-CTK222 was modified with a Lys-63-linked tetraubiquitin chain. Reaction conditions were as follows: 125 nm E1, 750 nm UbcH7, 500 nm WWP1, 300 nm His6- WBP2-CTK222, and 7.5 μm Lys-63-linked Ub4. The reaction was incubated at 37 °C for 20 s and placed back on ice, and a second round of reaction was initiated by adding a molar excess of 0K Ub (50 μm). The reaction was again incubated at 37 °C. Time points were withdrawn at the indicated times and quenched in denaturing buffer, and the ubiquitinated WBP2-CTK222 reaction products were subsequently purified on TALON beads. The reaction products were resolved by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by anti-Ub immunoblotting.

Author contributions

M. E. F., J. L. K., A. A., and T. H. designed the research. M. E. F. conceived the idea for the project and performed all experiments, except for fluorescence anisotropy (performed by J. L. K.) and mass spectrometry (performed by A. A.). M. E. F., J. L. K., A. A., and T. H. analyzed the data. M. E. F., J. L. K., and A. A. wrote the paper with input from T. H., S. I. R., and J. R. Y. All authors reviewed the paper and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We thank Linda Hicke (University of Texas at Austin), Marius Sudol (Institute of Molecular and Cell Biology, Singapore), and Brenda Schulman (St. Jude Children's Research Hospital) for constructs and advice. We are grateful to Sarah Rice, Peter Douglas, and David Krist for comments on the manuscript. We acknowledge use of the Keck Biophysics Facility at Northwestern University for fluorescence anisotropy experiments.

This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grants P30CA014195, R01CA080100, and R01CA082683 (to T. H.); National Institutes of Health Grant R01GM072656 (in support of J. L. K., to Dr. Sarah Rice); National Institutes of Health Grant P41GM103533 (to J. R. Y.); and National Institutes of Health Grant R01GM115170 (to S. I. R.). The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

- Ub

- ubiquitin

- HECT

- homologous to E6AP C terminus

- RING

- really interesting new gene

- 0K

- lysine-less

- PDB

- Protein Data Bank

- β-ME

- β-mercaptoethanol

- Tricine

- N-tris(hydroxymethyl)methylglycine.

References

- 1. Komander D., and Rape M. (2012) The ubiquitin code. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 81, 203–229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kulathu Y., and Komander D. (2012) Atypical ubiquitylation–the unexplored world of polyubiquitin beyond Lys48 and Lys63 linkages. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 13, 508–523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Husnjak K., and Dikic I. (2012) Ubiquitin-binding proteins: decoders of ubiquitin-mediated cellular functions. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 81, 291–322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Deshaies R. J., and Joazeiro C. A. (2009) RING domain E3 ubiquitin ligases. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 78, 399–434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Metzger M. B., Pruneda J. N., Klevit R. E., and Weissman A. M. (2014) RING-type E3 ligases: master manipulators of E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes and ubiquitination. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1843, 47–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Berndsen C. E., and Wolberger C. (2014) New insights into ubiquitin E3 ligase mechanism. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 21, 301–307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rotin D., and Kumar S. (2009) Physiological functions of the HECT family of ubiquitin ligases. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 10, 398–409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Smit J. J., and Sixma T. K. (2014) RBR E3-ligases at work. EMBO Rep. 15, 142–154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Spratt D. E., Walden H., and Shaw G. S. (2014) RBR E3 ubiquitin ligases: new structures, new insights, new questions. Biochem. J. 458, 421–437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bernassola F., Karin M., Ciechanover A., and Melino G. (2008) The HECT family of E3 ubiquitin ligases: multiple players in cancer development. Cancer Cell 14, 10–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Imamura T., Oshima Y., and Hikita A. (2013) Regulation of TGF-β family signalling by ubiquitination and deubiquitination. J. Biochem. 154, 481–489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Boase N. A., and Kumar S. (2015) NEDD4: the founding member of a family of ubiquitin-protein ligases. Gene 557, 113–122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Venuprasad K., Zeng M., Baughan S. L., and Massoumi R. (2015) Multifaceted role of the ubiquitin ligase Itch in immune regulation. Immunol. Cell Biol. 93, 452–460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kamadurai H. B., Souphron J., Scott D. C., Duda D. M., Miller D. J., Stringer D., Piper R. C., and Schulman B. A. (2009) Insights into ubiquitin transfer cascades from a structure of a UbcH5B∼ubiquitin-HECT(NEDD4L) complex. Mol. Cell 36, 1095–1102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kamadurai H. B., Qiu Y., Deng A., Harrison J. S., Macdonald C., Actis M., Rodrigues P., Miller D. J., Souphron J., Lewis S. M., Kurinov I., Fujii N., Hammel M., Piper R., Kuhlman B., et al. (2013) Mechanism of ubiquitin ligation and lysine prioritization by a HECT E3. Elife 2, e00828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Maspero E., Valentini E., Mari S., Cecatiello V., Soffientini P., Pasqualato S., and Polo S. (2013) Structure of a ubiquitin-loaded HECT ligase reveals the molecular basis for catalytic priming. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 20, 696–701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ronchi V. P., Klein J. M., Edwards D. J., and Haas A. L. (2014) The active form of E6-associated protein (E6AP)/UBE3A ubiquitin ligase is an oligomer. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 1033–1048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Verdecia M. A., Joazeiro C. A., Wells N. J., Ferrer J. L., Bowman M. E., Hunter T., and Noel J. P. (2003) Conformational flexibility underlies ubiquitin ligation mediated by the WWP1 HECT domain E3 ligase. Mol. Cell 11, 249–259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wang M., and Pickart C. M. (2005) Different HECT domain ubiquitin ligases employ distinct mechanisms of polyubiquitin chain synthesis. EMBO J. 24, 4324–4333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kim H. C., and Huibregtse J. M. (2009) Polyubiquitination by HECT E3s and the determinants of chain type specificity. Mol. Cell. Biol. 29, 3307–3318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Maspero E., Mari S., Valentini E., Musacchio A., Fish A., Pasqualato S., and Polo S. (2011) Structure of the HECT:ubiquitin complex and its role in ubiquitin chain elongation. EMBO Rep. 12, 342–349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ronchi V. P., Klein J. M., and Haas A. L. (2013) E6AP/UBE3A ubiquitin ligase harbors two E2∼ubiquitin binding sites. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 10349–10360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hochstrasser M. (2006) Lingering mysteries of ubiquitin-chain assembly. Cell 124, 27–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. French M. E., Kretzmann B. R., and Hicke L. (2009) Regulation of the RSP5 ubiquitin ligase by an intrinsic ubiquitin-binding site. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 12071–12079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ogunjimi A. A., Wiesner S., Briant D. J., Varelas X., Sicheri F., Forman-Kay J., and Wrana J. L. (2010) The ubiquitin binding region of the Smurf HECT domain facilitates polyubiquitylation and binding of ubiquitylated substrates. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 6308–6315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kim H. C., Steffen A. M., Oldham M. L., Chen J., and Huibregtse J. M. (2011) Structure and function of a HECT domain ubiquitin-binding site. EMBO Rep. 12, 334–341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Zhang W., Wu K. P., Sartori M. A., Kamadurai H. B., Ordureau A., Jiang C., Mercredi P. Y., Murchie R., Hu J., Persaud A., Mukherjee M., Li N., Doye A., Walker J. R., Sheng Y., et al. (2016) System-wide modulation of HECT E3 ligases with selective ubiquitin variant probes. Mol. Cell 62, 121–136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kim H. T., Kim K. P., Lledias F., Kisselev A. F., Scaglione K. M., Skowyra D., Gygi S. P., and Goldberg A. L. (2007) Certain pairs of ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes (E2s) and ubiquitin-protein ligases (E3s) synthesize nondegradable forked ubiquitin chains containing all possible isopeptide linkages. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 17375–17386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Beaudenon S., and Huibregtse J. M. (2008) HPV E6, E6AP and cervical cancer. BMC Biochem. 9, Suppl. 1, S4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Michel M. A., Elliott P. R., Swatek K. N., Simicek M., Pruneda J. N., Wagstaff J. L., Freund S. M., and Komander D. (2015) Assembly and specific recognition of Lys-29- and Lys-33-linked polyubiquitin. Mol. Cell 58, 95–109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kristariyanto Y. A., Choi S. Y., Rehman S. A., Ritorto M. S., Campbell D. G., Morrice N. A., Toth R., and Kulathu Y. (2015) Assembly and structure of Lys33-linked polyubiquitin reveals distinct conformations. Biochem. J. 467, 345–352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Galan J. M., and Haguenauer-Tsapis R. (1997) Ubiquitin Lys63 is involved in ubiquitination of a yeast plasma membrane protein. EMBO J. 16, 5847–5854 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Stawiecka-Mirota M., Pokrzywa W., Morvan J., Zoladek T., Haguenauer-Tsapis R., Urban-Grimal D., and Morsomme P. (2007) Targeting of Sna3p to the endosomal pathway depends on its interaction with Rsp5p and multivesicular body sorting on its ubiquitylation. Traffic 8, 1280–1296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sheng Y., Hong J. H., Doherty R., Srikumar T., Shloush J., Avvakumov G. V., Walker J. R., Xue S., Neculai D., Wan J. W., Kim S. K., Arrowsmith C. H., Raught B., and Dhe-Paganon S. (2012) A human ubiquitin conjugating enzyme (E2)-HECT E3 ligase structure-function screen. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 11, 329–341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Chastagner P., Israël A., and Brou C. (2006) Itch/AIP4 mediates Deltex degradation through the formation of Lys-29-linked polyubiquitin chains. EMBO Rep. 7, 1147–1153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lee Y. S., Park J. S., Kim J. H., Jung S. M., Lee J. Y., Kim S. J., and Park S. H. (2011) Smad6-specific recruitment of Smurf E3 ligases mediates TGF-β1-induced degradation of MyD88 in TLR4 signalling. Nat. Commun. 2, 460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Yang Y., Liao B., Wang S., Yan B., Jin Y., Shu H. B., and Wang Y. Y. (2013) E3 ligase WWP2 negatively regulates TLR3-mediated innate immune response by targeting TRIF for ubiquitination and degradation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 5115–5120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Fang N. N., Chan G. T., Zhu M., Comyn S. A., Persaud A., Deshaies R. J., Rotin D., Gsponer J., and Mayor T. (2014) Rsp5/Nedd4 is the main ubiquitin ligase that targets cytosolic misfolded proteins following heat stress. Nat. Cell Biol. 16, 1227–1237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Xu P., Duong D. M., Seyfried N. T., Cheng D., Xie Y., Robert J., Rush J., Hochstrasser M., Finley D., and Peng J. (2009) Quantitative proteomics reveals the function of unconventional ubiquitin chains in proteasomal degradation. Cell 137, 133–145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Dammer E. B., Na C. H., Xu P., Seyfried N. T., Duong D. M., Cheng D., Gearing M., Rees H., Lah J. J., Levey A. I., Rush J., and Peng J. (2011) Polyubiquitin linkage profiles in three models of proteolytic stress suggest the etiology of Alzheimer disease. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 10457–10465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Emmerich C. H., Ordureau A., Strickson S., Arthur J. S., Pedrioli P. G., Komander D., and Cohen P. (2013) Activation of the canonical IKK complex by Lys-63/M1-linked hybrid ubiquitin chains. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 15247–15252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ordureau A., Sarraf S. A., Duda D. M., Heo J. M., Jedrychowski M. P., Sviderskiy V. O., Olszewski J. L., Koerber J. T., Xie T., Beausoleil S. A., Wells J. A., Gygi S. P., Schulman B. A., and Harper J. W. (2014) Quantitative proteomics reveal a feedforward mechanism for mitochondrial PARKIN translocation and ubiquitin chain synthesis. Mol. Cell 56, 360–375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Meyer H. J., and Rape M. (2014) Enhanced protein degradation by branched ubiquitin chains. Cell 157, 910–921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Wang M., Cheng D., Peng J., and Pickart C. M. (2006) Molecular determinants of polyubiquitin linkage selection by an HECT ubiquitin ligase. EMBO J. 25, 1710–1719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Hospenthal M. K., Freund S. M., and Komander D. (2013) Assembly, analysis and architecture of atypical ubiquitin chains. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 20, 555–565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Valkevich E. M., Sanchez N. A., Ge Y., and Strieter E. R. (2014) Middle-down mass spectrometry enables characterization of branched ubiquitin chains. Biochemistry 53, 4979–4989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Chen C., Sun X., Guo P., Dong X. Y., Sethi P., Cheng X., Zhou J., Ling J., Simons J. W., Lingrel J. B., and Dong J. T. (2005) Human Kruppel-like factor 5 is a target of the E3 ubiquitin ligase WWP1 for proteolysis in epithelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 41553–41561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. van Wijk S. J., and Timmers H. T. (2010) The family of ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes (E2s): deciding between life and death of proteins. FASEB J. 24, 981–993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Persaud A., Alberts P., Amsen E. M., Xiong X., Wasmuth J., Saadon Z., Fladd C., Parkinson J., and Rotin D. (2009) Comparison of substrate specificity of the ubiquitin ligases Nedd4 and Nedd4–2 using proteome arrays. Mol. Syst. Biol. 5, 333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Kathman S. G., Span I., Smith A. T., Xu Z., Zhan J., Rosenzweig A. C., and Statsyuk A. V. (2015) A small molecule that switches a ubiquitin ligase from a processive to a distributive enzymatic mechanism. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 12442–12445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Carrano A. C., Liu Z., Dillin A., and Hunter T. (2009) A conserved ubiquitination pathway determines longevity in response to diet restriction. Nature 460, 396–399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Kee Y., Lyon N., and Huibregtse J. M. (2005) The Rsp5 ubiquitin ligase is coupled to and antagonized by the Ubp2 deubiquitinating enzyme. EMBO J. 24, 2414–2424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Peschiaroli A., Scialpi F., Bernassola F., El Sherbini el S., Melino G. (2010) The E3 ubiquitin ligase WWP1 regulates ΔNp63-dependent transcription through Lys63 linkages. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 402, 425–430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]