Abstract

Background

Extracts of Poncirus trifoliata (L.) Raf. (Rutaceae; PT) are widely used as a traditional medicine in Eastern Asia, especially for the treatment of gastrointestinal (GI) disorders related to GI motility. Interstitial cells of Cajal (ICCs) are pacemakers in the GI tract, and transient receptor potential melastatin type 7 (TRPM7) channels and Ca2+ activated Cl– channels are candidate pacemaker channels.

Methods

In the present study, the effects of a methanolic extract of the dried roots of PT on ICC pacemaking activity were examined using the whole-cell patch-clamp technique.

Results

The methanolic extract of PT (PTE) was found to decrease the amplitudes of pacemaker potentials in ICC clusters and to depolarize the resting membrane potentials in a concentration-dependent manner. Intracellular GDP-β-S suppressed PTE-induced depolarizations, and pretreatment with a U-73122 (a phospholipase C inhibitor) or with 2-APB (an 1,4,5-inositol triphosphate receptor inhibitor) abolished this generation of pacemaker potentials and suppressed PTE-induced effects. The applications of flufenamic acid, niflumic acid, waixenicin A, or 5-lipoxygenase inhibitors (NDGA or AA861) abolished this generation of pacemaker potentials and inhibited PTE-induced membrane depolarization. Furthermore, PTE inhibited TRPM7 channels but did not affect Ca2+-activated Cl– channels (both channels play important roles in the modulation of the pacemaking activity related to GI motility).

Conclusion

These results suggest that the PTE-induced depolarization of pacemaking activity occurs in a G-protein-, phospholipase C-, and 1,4,5-inositol triphosphate-dependent manner via TRPM7 channels in cultured ICCs from murine small intestine, which indicates that ICCs are PTE targets and that their interactions affect intestinal motility.

Keywords: Ca2+ activated Cl– channels, interstitial cells of Cajal, Poncirus trifoliata (L.) Raf.TRPM7

1. Introduction

The dried roots of Poncirus trifoliata (L.) Raf. (Rutaceae, PT) are widely used as a traditional medicine in Eastern Asia, especially in Korean traditional medicine, for the treatment of gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms related to abnormal GI motility and gastric secretion.1, 2, 3, 4 Despite the widespread use of PT-sourced medications for the treatment of GI dysfunction, the manner in which PT regulates small intestine motility is not understood. PT accelerates small bowel transit in rats without affecting gastric emptying,3 and has been suggest to have therapeutic utility for the treatment of GI motility abnormalities.4 In addition, PT stimulation of distal colon motility in the rat has been described.5 These observations suggest that PT has therapeutic potential for treatment of GI motility disorders.

Interstitial cells of Cajal (ICCs) are the pacemaking cells of the GI muscles that generate rhythmic oscillations (known as slow waves) in the electrical potential membrane.6, 7 Pacemaker activities in murine small intestine are mainly attributable to periodic activations of nonselective cation channels (NSCCs)8 or Cl– channels.9, 10 ICCs also mediate or transduce inputs from the enteric nervous system, and because of the central role played by ICCs in GI motility, loss of these cells would be extremely detrimental. We previously suggested that, as a primary molecular candidate for the NSCCs responsible for pacemaking activity in ICCs, transient receptor potential melastatin 7 (TRPM7) is required for pacemaking activity in murine small intestine.11 Zhu et al10 suggested that Ca2+-activated Cl– channel is involved in the generation of slow wave currents in ICCs and that this channel is transmembrane protein 16A, Tmem16a, which encodes anoctamin 1 (ANO1) channels expressed in human embryonic kidney (HEK)-293 cells.12 Accordingly, TRPM7 and Ano1 are considered potential pharmacological treatments for GI motility disorders.

Therefore, we investigated the effect of PT on the electrical properties of cultured ICC clusters derived from the murine small intestine and to identify the ion channels involved in __.

2. Methods

2.1. Preparation of P. trifoliata (L.) Raf. extract

Dried roots of P. trifoliata (L.) Raf. (Rutaceae, PT) were purchased from Kwangmyungdang Medicinal Herbs (Ulsan, South Korea). PT was immersed in 1000 mL methanol, sonicated for 30 minutes, and left to stand for 24 hours. The extract obtained was filtered through Whatman filter paper (No. 20) and evaporated under reduced pressure using a vacuum evaporator (Eyela, Tokyo, Japan). The condensed extract was then lyophilized using a freeze dryer (Labconco Corp., Kansas City, MO, USA). Finally, 6.43 g of lyophilized powder (PTE) was obtained (yield; 12.9%).

2.2. Chromatographic conditions and preparation of standard

We used a smart LC system composed of LC800 (GL Sciences, Tokyo, Japan) with a built-in solvent delivery unit, autosampler, column oven, and UV–visible detector. Acquired data were processed using EZChrom Elite software (version 3.3.2 SP1, Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan). Chromatographic separation was performed using an Inertsil ODS-4 column (2.1 × 50 mm, 2 μm; GL Sciences) at 35 °C. The mobile phase consisted of water (A) and acetonitrile (B), using the following gradient: 5% (B) maintained for 5 minutes and 5–90% (B) over 5–7 minutes. The flow rate was set at 0.4 mL/min, and the volume injected was 1 μL. Poncirin was used as a positive standard. One milligram of poncirin was accurately weighed and dissolved in methanol to 100 μg/mL and diluted 10-fold before the injection.

2.3. Preparation of cells and cell cultures

All animals used were treated according to the Guidelines for the Care and Use of Animals issued by Pusan National University. Balb/c mice (8–13 days old) of either sex were anesthetized with ether and sacrificed by cervical dislocation. In each animal, the small intestine from 1 cm below the pyloric ring to the cecum was removed and opened along the mesenteric border. Luminal contents were washed out with Krebs–Ringer bicarbonate solution. The tissues were pinned to the base of a Sylgard dish, and the mucosa was removed by sharp dissection; then, small strips of intestinal muscle (both circular and longitudinal muscle) were equilibrated in Ca2+ free Hank's solution containing 5.36 mM KCl, 125 mM NaCl, 0.34 mM NaOH, 0.44 mM Na2HCO3, 10 mM glucose, 2.9 mM sucrose, and 11 mM N-(2-hydroxyethyl)piperazine-N-2-ethanesulfonic acid (HEPES) for 30 minutes. Cells were then dispersed using a solution containing 1.3 mg/mL collagenase (Worthington Biochemical Corp., Lakewood, NJ, USA), 2 mg/mL bovine serum albumin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), 2 mg/mL trypsin inhibitor (Sigma-Aldrich), and 0.27 mg/mL ATP. Dispersed cells were plated onto sterile glass coverslips coated with 2.5 mg/mL murine collagen (Falcon/BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) in 35-mm culture dishes and cultured at 37 °C in a 95% O2/5% CO2 incubator in smooth muscle growth medium (Clonetics Corp., San Diego, CA, USA) supplemented with 2% antibiotics/antimycotics (Gibco, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) and 5 ng/mL of murine stem cell factor (Sigma-Aldrich). ICCs were identified immunologically by incubating them with anti-c-kit antibody (phycoerythrin-conjugated rat antimouse c-kit monoclonal antibody; eBioscience Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) at a dilution of 1:50 for 20 minutes. Because the ICC morphology differed from the morphologies of other cell types in culture, it was possible to identify them by phase contrast microscopy after incubation with anti-c-kit antibody.

2.4. Patch-clamp experiments

The physiological salt solution used to bathe cells (Na+-Tyrode) contained 5 mM KCl, 135 mM NaCl, 2 mM CaCl2, 10 mM glucose, 1.2 mM MgCl2, and 10 mM HEPES, adjusted to pH 7.4 with NaOH. The pipette solution contained 140 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 2.7 mM K2ATP, 0.1 mM NaGTP, 2.5 mM creatine phosphate disodium, 5 mM HEPES, and 0.1 mM ethylene glycol bis(2-aminoethyl ether)-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid (EGTA), adjusted to pH 7.2 with KOH. Single ICCs were bathed in a solution containing 2.8 mM KCl, 145 mM NaCl, 2 mM CaCl2, 10 mM glucose, 1.2 mM MgCl2, and 10 mM HEPES, adjusted to pH 7.4 with NaOH. The pipette solution contained 145 mM Cs-glutamate, 8 mM NaCl, 10 mM Cs-2-bis(2-aminophenoxy)-ethane-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid, and 10 mM HEPES–CsOH, adjusted to pH 7.2 with CsOH. The whole-cell configuration patch-clamp technique was used to record membrane potentials (current clamp) of cultured ICCs, and an Axopatch I-D (Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA, USA) was used to amplify membrane currents and potentials. A voltage ramp from + 100 mV to –100 mV was applied from a holding potential of –60 mV. Command pulses were applied using an IBM-compatible personal computer and pClamp software (version 6.1; Axon Instruments). Data were filtered at 5 kHz and displayed on an oscilloscope and a computer monitor, and printed out using a Gould 2200 pen recorder (Gould Instrument Systems Inc., Valley View, OH, USA), and analyzed with pClamp and Origin (version 6.0; Axon Instruments) software. All experiments were performed at 30 °C.

2.5. TRPM7 expression in human embryonic kidney-293 cells

HEK-293 cells transfected with Flag-murine LTRPC7/pCDNA4-TO construct were grown on glass coverslips in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, blasticidin (5 μg/mL), and zeocin (0.4 mg/mL). TRPM7 (LTRPC7) expression was induced by adding 1 μg/mL tetracycline to the culture medium. Whole-cell patch-clamp experiments were performed at 21–25 °C 24 hours after induction using cells grown on glass coverslips. The solutions used were the same as those used for recording whole-cell currents in ICCs.

2.6. Ca2+ activated Cl– channel expression in HEK-293 cells

HEK-293 cells transfected with the pEGFP-N1-mANO1 construct were grown on glass coverslips in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. Whole-cell patch-clamp experiments were performed at 21–25 °C 24 hours after induction using cells grown on glass coverslips. Bath and pipette solutions with N-methyl-d-glucamine (NMDG) contained 146 mM HCl, 10 mM HEPES, 10 mM glucose, 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM CaCl2 or 134 mM HCl, 5 mM HEPES, 3 mM Mg-ATP, 1 mM MgCl2, 7 mM CaCl2, and 10 mM EGTA, and were adjusted to pH 7.2 (or pH 7.4) using NMDG.

2.7. Drugs

Drugs were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. To produce stock solutions, all drugs were dissolved in distilled water or dimethylsulfoxide and stored at –20 °C. The final concentration of dimethylsulfoxide in the bath solution was always < 0.1%, and at this level it did not affect the recorded traces.

2.8. Statistics

All data are expressed as means ± SE. The Student t test for unpaired data was used to compare control and experimental groups. Statistical significance was accepted for p < 0.05.

3. Results

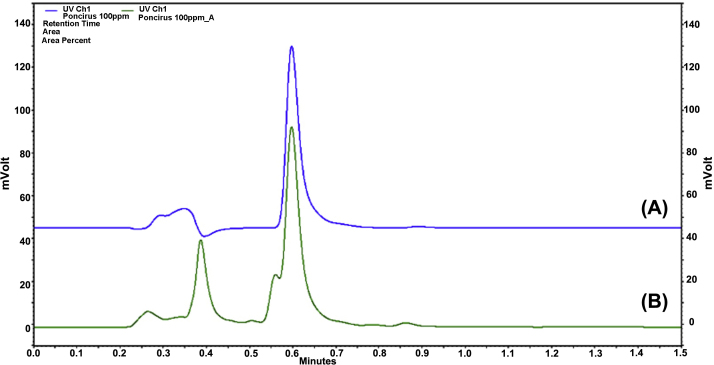

Initially, we identified poncirin in Poncirus trifoliata (L.) Raf. extract (PTE). Poncirin had a retention time of 0.6 minute in PTE and in PFI extract (Fig. 1A). The poncirin peak in PTE was larger than the other peaks detected with a retention time of < 1.5 minutes despite interference from an adjacent peak (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

Chromatograms of (A) poncirin and of (B) Ponciri Fructus Immaturus extract at a UV wavelength of 280 nm.

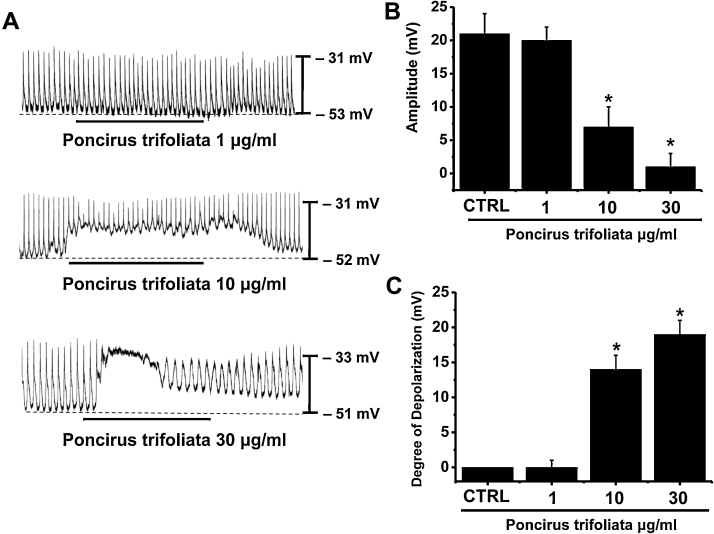

ICCs are involved in physiological GI motility, and therefore, are of clinical importance in many bowel disorders, such as inflammatory bowel disease, chronic idiopathic intestinal pseudo-obstruction, intestinal obstruction with hypertrophy, achalasia, Hirschsprung's disease, juvenile pyloric stenosis, juvenile intestinal obstruction, and anorectal malformation.13 The discovery of molecules involved in the generation of pacemaker activity in ICCs can lead to new therapies for chronic GI diseases that result in lifelong suffering. The patch-clamp technique was used on ICCs with network-like structures in culture (2–4 days). During the study, spontaneous rhythmicity was routinely recorded from cultured ICCs under current and voltage-clamp conditions, and ICCs within networks were observed to have more robust electrical rhythmicity. In a previous study, tissue-like spontaneous slow waves were recorded from ICCs.14 To understand the relationship between PTE and the modulation of pacemaker activity in ICCs, we examined the effects of PTE on pacemaker potentials in ICC clusters. In current clamp mode (I = 0), ICCs had a mean resting membrane potential of –52.1 ± 1.4 mV and produced electrical pacemaker potentials (n = 30). The mean frequency of these pacemaker potentials was 17 ± 3 cycles/min and the amplitude was 22.4 ± 1.6 mV (n = 30; Fig. 2A). The addition of PTE (1–30 μg/mL) decreased the amplitudes of pacemaker potentials and depolarized resting membrane potentials in a concentration dependent manner (Fig. 2A–2C). In the presence of PTE, amplitudes were 20.1 ± 2.2 mV at 1 μg/mL, 7.3 ± 3.2 mV at 10 μg/mL, and 1 ± 1.2 mV at 30 μg/mL (Fig. 2B, n = 5). Corresponding mean resting membrane depolarizations were 0.2 ± 1.0 mV, 14.2 ± 2.3 mV, and 19.3 ± 2.1 mV (Fig. 2C, n = 5). These results suggest that PTE decreased the amplitudes of pacemaker potentials in a dose-dependent manner in ICC clusters.

Fig. 2.

Poncirus trifoliata (L.) Raf. extract (PTE) decreased the amplitudes of pacemaker potentials in cultured interstitial cells of Cajal (ICCs) clusters. (A) Pacemaking activities of ICCs exposed to PTE (1–30 μg/mL) in current-clamp mode (I = 0). PTE caused membrane depolarization concentration-dependently and reduced the amplitudes of pacemaking activities. Responses to PTE are summarized in (B) and (C). Bars represent mean value ± SE. CTRL, control. *p < 0.01; significantly different from the control.

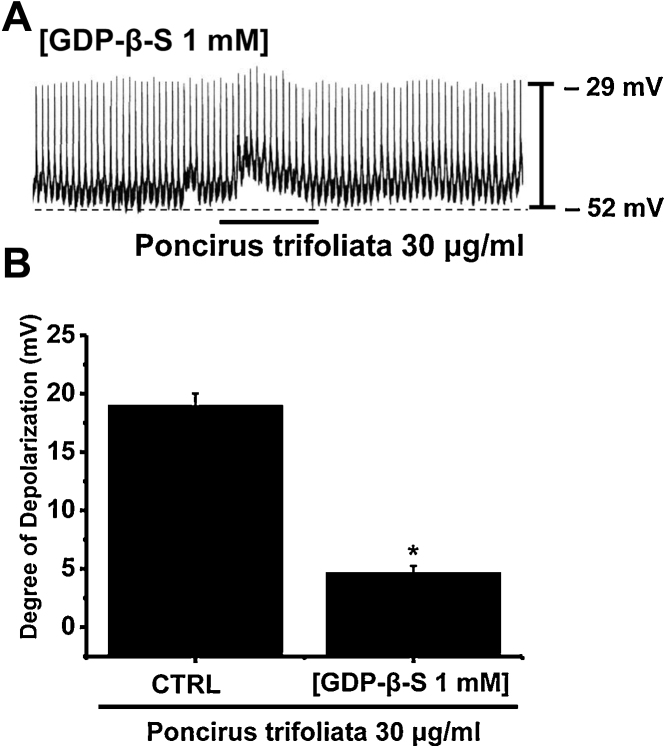

A G-protein-mediated signal transduction pathway is believed to play a key role in the gating process of receptor-operated cationic channel.15 To investigate the involvement of G protein on the PTE-induced depolarization of pacemaker potentials in ICC clusters, the effects of GDP-β-S (a nonhydrolyzable guanosine 5′-diphosphate analogue that permanently inactivates G-protein binding proteins)15 were examined to determine whether G-proteins are involved in the effects of PTE on ICCs. When GDP-β-S (1 mmol/L) was in the pipette solution, PTE (30 μg/mL) did not induce membrane depolarization (Fig. 3A). However, the membrane depolarizations induced by PTE were significantly affected by GDP-β-S (1 mmol/L) in the pipette solution (n = 4; Fig. 3B). These results suggest that the effect of PTE might be mediated by G proteins.

Fig. 3.

Effects of GDP-β-S in the pipette on Poncirus trifoliata (L.) Raf. extract (PTE)-induced depolarizations of pacemaker potentials in cultured interstitial cells of Cajal (ICCs) clusters. (A) Pacemaker potentials in ICCs exposed to PTE in the presence of GDP-β-S (1 mM) in the pipette. Under these conditions, PTE (30 μg/mL) had no effects. (B) Responses to PTE in the presence of GDP-β-S in the pipette are summarized. Bars represent mean value ± SE. CTRL, control. *p < 0.01; significantly different from the control.

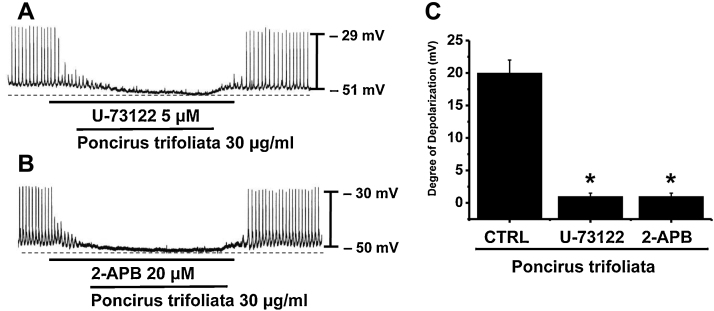

Because the membrane depolarizations produced by PTE were related with intracellular Ca2+ mobilization, we considered that PTE-induced effects on pacemaker potentials probably required phospholipase C (PLC) activation. To test this possibility, PTE-induced depolarizations were measured in the presence or absence of U-73122 (an active PLC inhibitor). Pacemaker potentials were completely abolished by U-73122 (5 μM, n = 4; Fig. 4A). Furthermore, in the presence of U-73122, the membrane depolarizations produced by PTE had no effects. In addition, the degree of depolarization differed significantly from that caused by PTE in the absence of U-73122 (n = 4; Fig. 4C). To determine the involvement of 1,4,5-inositol triphosphate (IP3) receptors in the membrane depolarizations induced by PTE, we used 2-APB (an antagonist of IP3 receptors). Pacemaker potentials were completely abolished by the application of 2-APB (20 μM) (n = 4; Fig. 4B), and PTE had no effect on membrane depolarization in the presence of 2-APB. These findings show that the PLC–IP3 pathway is involved in the PTE-induced depolarizations in ICC clusters.

Fig. 4.

Effects of U-73122 and 2-APB on the Poncirus trifoliata (L.) Raf. extract (PTE)-induced pacemaker potential responses of cultured interstitial cells of Cajal (ICCs) clusters. (A) Pacemaking activities of ICCs exposed to PTE in the presence of U-73122 (5 μM). U-73122 blocked PTE-induced pacemaking activity depolarizations. (B) 2-APB (20 μM) abolished the generation of pacemaker potentials. 2-APB also blocked the PTE-induced depolarizations of pacemaking activity. Responses to PTE in the presence of U-73122 or 2-APB are summarized in (C). Bars represent mean value ± SE. CTRL, control. *p < 0.01; significantly different from the control.

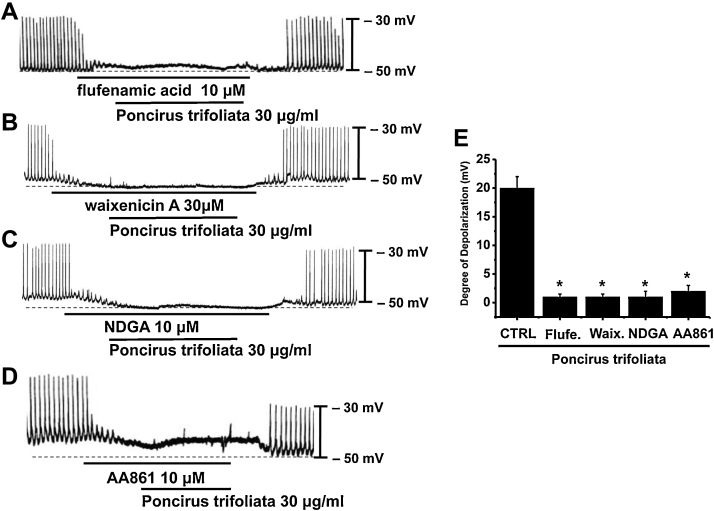

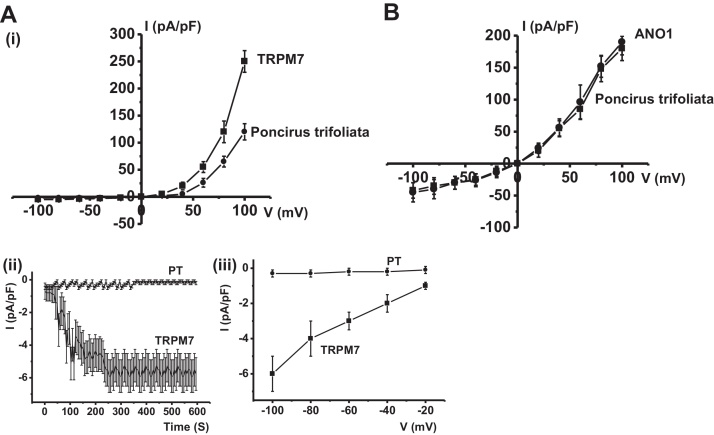

The pacemaker activity of murine small intestine is mainly attributable to the periodic activation of NSCCs8, 16 or Cl– channels.9, 10 In a previous study, we suggested that the electrophysiological and pharmacological properties of TRPM7 and of NSCCs in ICCs are the same, and that therefore, TRPM7 protein is an essential molecular component of NSCCs in ICCs.11 Also, Hwang et al17 and Zhu et al10 suggested that Ca2+-activated Cl– conductance is also involved in slow wave current in ICCs and that Ano1 participates in pacemaker activity. To determine the characteristics of pacemaker potentials induced by PTE, flufenamic acid (an NSCC blocker), or niflumic acid (a Cl– channel blocker) were used. In the presence of flufenamic acid (10 μM) or niflumic acid (10 μM), spontaneous potentials were abolished and the subsequent application of PTE had no effect (n = 3; Fig. 4A and data not shown). Recently, Chen et al18 suggested that the 5-LOX inhibitors NDGA, AA861, and MK886 reduced TRPM7 channel activity independently of their effects on 5-LOX activity, and that the application of AA861 or NDGA reduced the cell deaths of cells overexpressing TRPM7 and cultured with low extracellular divalent cations. In a recent study, we found that NDGA or AA861 reduced the amplitudes of pacemaker potentials in cultured ICCs but had little effect on resting membrane potentials,19 and thus, we suggested that NDGA and AA861 inhibit expressed TRPM7 in cultured ICCs and modulate the ICC pacemaker activities. In addition, Zierler et al20 reported that waixenicin A blocked TRPM7 channels. To investigate the involvement of TRPM7 in PTE-induced depolarization, we used waixenicin A, NDGA, or AA861. In the presence of waixenicin A, NDGA, or AA861, spontaneous potentials were abolished, and the subsequent application of PTE had no effect (n = 4; Fig. 5). These results suggest that TRPM7 or Cl– channel might be involved in PTE-induced response in cultured ICC clusters. To determine which channel is involved, we examined the effects of PTE on TRPM7 and Ca2+-activated Cl– channels. We found that PTE inhibited the activities of TRPM7 channels, but did not affect Ca2+-activated Cl– channels (n = 4; Fig. 6), showing that the effects of PTE were attributable to TRPM7 channels and not to Ca2+-activated Cl– channels. Taken together, PTE decreased the amplitude of pacemaker potentials and depolarized resting membrane potentials in a concentration-dependent manner. Furthermore, our findings show that the inhibition of pacemaker activity by PTE was due to the PLC–IP3 pathway in ICC clusters in the murine small intestine, and that PTE-induced response occurred through TRPM7 channels, and not Ca2+-activated Cl– channels.

Fig. 5.

Effects of flufenamic acid, waixenicin A, NDGA, and AA861 on the Poncirus trifoliata (L.) Raf. extract (PTE)-induced pacemaker potential responses of cultured interstitial cells of Cajal (ICCs) clusters. (A–D) Application of flufenamic acid, waixenicin A, NDGA, or AA861 abolished the generation of pacemaker potentials. Under these conditions, PTE did not produce membrane depolarization. Responses to PTE in the presence of flufenamic acid, waixenicin A, NDGA, or AA861 are summarized in (E). Bars represent mean value ± SE. CTRL, control. *p < 0.01, significantly different from the control.

Fig. 6.

Effects of Poncirus trifoliata (L.) Raf. extract (PTE) on overexpressed transient receptor potential melastatin type 7 (TRPM7) and Ca2+-activated Cl– channels in human embryonic kidney (HEK)-293 cells. (A) (i) Representative I–V relationships of the effect of PTE on TRPM7 currents in HEK293 cells. (ii) The time course of the current traces in (i) are plotted as inward currents at –100 mV. (iii) Enlargement of the negative potential region of (i). (B) Representative I–V relationships of the effect of PTE on Ca2+-activated Cl– currents in HEK293 cells. A voltage ramp from + 100 mV to –100 mV was applied from a holding potential of –60 mV.

4. Discussion

The functions of TRPM7 and Ca2+-activated Cl– conductances in the GI tract remain unclear. Nevertheless, it has been suggested that Ca2+-activated Cl– conductance expression in ICCs may be involved in human diabetic gastroparesis21 and that TRPM7 has an important role in gastric cancer cell death.16 However, the functions of TRPM7 and Ca2+-activated Cl– conductances in GI tract require further investigation.

TRPM7 has been suggested to play central roles in cellular Mg2+ homeostasis,22 central nervous system ischemic injury,23 skeletogenesis in the zebrafish,24 defecation rhythm in Caenorhabditis elegans,25 cholinergic vesicle fusion with the plasma membrane,26 phosphoinositide-3-kinase signaling in lymphocytes,27 cell death in gastric cancer,16 osteoblast proliferation,28 and breast cancer cell proliferation.29 In the digestive tract, the physiological functions of TRPM7 have not been fully investigated and await to be explored.

PTE is commonly used to improve GI motility dysfunction in Korean traditional medicine, but the mechanism involved has not been studied. In the present study, we identified the molecular roles of PTE in ICCs from murine small intestine. Specifically, PTE was found to induce the depolarization of pacemaking activity in a G-protein-, PLC-, and IP3-dependent manner via TRPM7 channels, which are known to have important roles in the modulation of pacemaking activity required for GI motility. Investigations into the role and signaling of PTE in cultured ICCs from murine small intestine have led to important advancements in our understanding of the physiological and pathophysiological roles of PTE in GI motility. Furthermore, we expect that PTE improves GI motility dysfunction by depolarizing pacemaking activity in ICCs. Thus, our findings show that ICCs are PTE targets and that their interaction can affect intestinal motility.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing a conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Kim D.H., Bae E.A., Han M.J. Anti-Helicobacter pylori activity of the metabolites of poncirin from Poncirus trifoliata by human intestinal bacteria. Biol Pharm Bull. 1999;22:422–424. doi: 10.1248/bpb.22.422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yi J.M., Kim M.S., Koo H.N., Song B.K., Yoo Y.H., Kim H.M. Poncirus trifoliata fruit induces apoptosis in human promyelocytic leukemia cells. Clin Chim Acta. 2004;340:179–185. doi: 10.1016/j.cccn.2003.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee H.T., Seo E.K., Chung S.J., Shim C.K. Prokinetic activity of an aqueous extract from dried immature fruit of Poncirus trifoliata (L.) Raf. J Ethnopharmacol. 2005;102:131–136. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2005.05.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee H.T., Seo E.K., Chung S.J., Shim C.K. Effect of an aqueous extract of dried immature fruit of Poncirus trifoliata (L.) Raf. on intestinal transit in rodents with experimental gastrointestinal motility dysfunctions. J Ethnopharmacol. 2005;102:302–306. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2005.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Choi K.H., Jeong S.I., Hwang B.S., Lee J.H., Ryoo H.K., Lee S., Choi B.K., Jung K.Y. Hexane extract of Poncirus trifoliata (L.) Raf. stimulates the motility of rat distal colon. J Ethnopharmacol. 2010;127:718–724. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2009.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huizinga J.D., Thuneberg L., Kluppel M., Malysz J., Mikkelsen H.B., Bernstein A. W/kit gene required for interstitial cells of Cajal and for intestinal pacemaker activity. Nature. 1995;373:347–349. doi: 10.1038/373347a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sanders K.M. A case for interstitial cells of Cajal as pacemakers and mediators of neurotransmission in the gastrointestinal tract. Gastroenterology. 1996;111:492–515. doi: 10.1053/gast.1996.v111.pm8690216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koh S.D., Jun J.Y., Kim T.W., Sanders K.M. A Ca2+-inhibited nonselective cation conductance contributes to pacemaker currents in mouse interstitial cell of Cajal. J Physiol. 2002;540:803–814. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2001.014639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huizinga J.D., Zhu Y., Ye J., Molleman A. High-conductance chloride channels generate pacemaker currents in interstitial cells of Cajal. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:1627–1636. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.36549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhu M.H., Kim T.W., Ro S., Yan W., Ward S.M., Koh S.D. A Ca2+-activated Cl–conductance in interstitial cells of Cajal linked to slow wave currents and pacemaker activity. J Physiol. 2009;587:4905–4918. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.176206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim B.J., Lim H.H., Yang D.K., Jun J.Y., Chang I.Y., Park C.S. Melastatin-type transient receptor potential channel 7 is required for intestinal pacemaking activity. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:1504–1517. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang Y.D., Cho H., Koo J.Y., Tak M.H., Cho Y., Shim W.S. TMEM16A confers receptor-activated calcium-dependent chloride conductance. Nature. 2008;455:1210–1215. doi: 10.1038/nature07313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sanders K.M., Ordög T., Koh S.D., Torihashi S., Ward S.M. Development and plasticity of interstitial cells of Cajal. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 1999;11:311–338. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2982.1999.00164.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koh S.D., Sanders K.M., Ward S.M. Spontaneous electrical rhythmicity in cultured interstitial cells of Cajal from the murine small intestine. J Physiol. 1998;513:203–213. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.203by.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yoo H.Y., Park S.J., Seo E.Y., Park K.S., Han J.A., Kim K.S. Role of thromboxane A2-activated nonselective cation channels in hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction of rat. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2012;302:C307–C317. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00153.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim B.J., Park E.J., Lee J.H., Jeon J.H., Kim S.J., So I. Suppression of transient receptor potential melastatin 7 channel induces cell death in gastric cancer. Cancer Sci. 2008;99:2502–2509. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2008.00982.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hwang S.J., Blair P.J., Britton F.C., O’Driscoll K.E., Hennig G., Bayguinov Y.R. Expression of anoctamin 1/TMEM16A by interstitial cells of Cajal is fundamental for slow wave activity in gastrointestinal muscles. J Physiol. 2009;587:4887–4904. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.176198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen H.C., Xie J., Zhang Z., Su L.T., Yue L., Runnels L.W. Blockade of TRPM7 channel activity and cell death by inhibitors of 5-lipoxygenase. PLOS One. 2010;5:e11161. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim B.J., Nam J.H., Kim S.J. Effects of transient receptor potential channel blockers on pacemaker activity in interstitial cells of Cajal from mouse small intestine. Mol Cells. 2011;32:153–160. doi: 10.1007/s10059-011-1019-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zierler S., Yao G., Zhang Z., Kuo W.C., Pörzgen P., Penner R., Waixenicin A inhibits cell proliferation through magnesium-dependent block of transient receptor potential melastatin 7 (TRPM7) channels. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:39328–39335. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.264341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mazzone A., Bernard C.E., Strege P.R., Beyder A., Galietta L.J., Pasricha P.J. Altered expression of ano1 variants in human diabetic gastroparesis. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:13393–13403. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.196089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schmitz C., Perraud A.L., Johnson C.O., Inabe K., Smith M.K., Penner R. Regulation of vertebrate cellular Mg2+ homeostasis by TRPM7. Cell. 2003;114:191–200. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00556-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aarts M., Iihara K., Wei W.L., Xiong Z.G., Arundine M., Cerwinski W. A key role for TRPM7 channels in anoxic neuronal death. Cell. 2003;115:863–877. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)01017-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Elizondo M.R., Arduini B.L., Paulsen J., MacDonald E.L., Sabel J.L., Henion P.D. Defective skeletogenesis with kidney stone formation in dwarf zebrafish mutant for trpm7. Curr Biol. 2005;15:667–671. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.02.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vriens J., Owsianik G., Voets T., Droogmans G., Nilius B. Invertebrate TRP proteins as functional models for mammalian channels. Pflugers Arch. 2004;449:213–226. doi: 10.1007/s00424-004-1314-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brauchi S., Krapivinsky G., Krapivinsky L., Clapham D.E. TRPM7 facilitates cholinergic vesicle fusion with the plasma membrane. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:8304–8308. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800881105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sahni J., Scharenberg A.M. TRPM7 ion channels are required for sustained phosphoinositide 3-kinase signaling in lymphocytes. Cell Metab. 2008;8:84–93. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Abed E., Moreau R. Importance of melastatin-like transient receptor potential 7 and magnesium in the stimulation of osteoblast proliferation and migration by platelet derived growth factor. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2009;297:C360–C368. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00614.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guilbert A., Gautier M., Dhennin-Duthille I., Haren N., Sevestre H., Ouadid-Ahidouch H. Evidence that TRPM7 is required for breast cancer cell proliferation. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2009;297:C493–C502. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00624.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]