Abstract

National Health Insurance (NHI) in Korea has covered Korean medicine (KM) services including acupuncture, moxibustion, cupping, and herbal preparations since 1987, which represents the first time that an entire traditional medicine system was insured by an NHI scheme anywhere in the world. This nationwide insurance coverage led to a rapid increase in the use of KM, and the KM community became one of the main interest groups in the Korean healthcare system. However, due to the public's safety concern of and the stagnancy in demand for KM services, KM has been facing new challenges. This paper presents a brief history and the current structure of KM health insurance, and describes the critical issues related to KM insurance for in-depth understanding of the present situation.

Keywords: acupuncture, health insurance, herbal medicine, Korean Medicine, reimbursement, traditional medicine

1. Introduction

Despite the old theories and the experiences formed historically, East Asian medicines have played a unique role in modern healthcare, and have been successfully integrated into contemporary healthcare systems. In South Korea, North Korea, mainland China, and Taiwan, people use traditional medicine to treat their symptoms and illnesses at the primary care level, formal universities and colleges provide traditional medicine education, and the legal status of traditional doctors is almost equal to that of doctors of Western medicine (WM).1, 2, 3, 4 Among the aforementioned countries, South Korea has been of particular interest because of its modernization and development of traditional Korean Medicine (KM).

One of the distinct features of KM development is that the National Health Insurance (NHI) covers most of KM services, including, outpatient care, inpatient care, diagnosis, treatments, and medication, etc. The NHI coverage of KM led to a rapid increase in its use; the number of claims increased from 1.6 million in 1990 to 91.4 million in 2010.5 Moreover, based on the increased demand for KM services, it overcame its position on WM community's coattails and achieved a higher social status and greater popularity. For example, in the late 1990s and early 2000s the average matriculation score for students who entered the nation's 11 schools of KM was higher than for most Western medical schools in Korea.4

However, due to the recent growth of mega hospitals and the stagnancy in demand for KM services, KM has been facing new challenges. While the frequency of outpatient visits was maintained, the total amount of treatment using KM services has since been on the decline.5 The problems faced by KM and its doctors with respect to regaining the public's confidence, obtaining more comprehensive NHI coverage, and generally overcoming this recent and negative development remain to be resolved.

This paper presents the implementation, development process, and current structure of KM coverage in the NHI, and describes the critical issues on KM insurance. It is hoped that the experiences of traditional medicine insurance coverage in Korea could provide insights for international researchers and policymakers who pursue or manage the integration of unconventional medical therapies into the modern health insurance system.

2. Implementation of KM health insurance

In December 1984, the then Ministry of Health and Social Affairs launched a 2-year pilot project for NHI coverage of KM services for 26 KM clinics in Cheongju city and Cheongwon county. In this pilot project, the benefit coverage included outpatient visits, acupuncture, moxibustion, cupping, and herbal medication. At that time 98 crude herbal drugs were covered, and KM doctors were able to prescribe one of the 26 notified formulas that could be composed of 98 crude herbal drugs. The fee for outpatient visit was set equal to that for WM, and fees for acupuncture, herbal medicine, and other interventions were calculated based on market prices.6

The outcomes of the pilot project were largely optimistic; the rate of treatment episodes was higher than expected, there was a high demand for the expansion of the prescription list, and users reported a high level of satisfaction with the project.7 The Ministry of Health and Social Affairs decided in October 1986 to expand the pilot KM coverage project to implement a continuous, nationwide program, which it achieved in February 1987. Although other services were maintained as in the pilot project, the number of insured herbal medicines in the nationwide program was reduced from 98 to 68. Furthermore, although the insured form of herbal medicines in the initial pilot project comprised packages of crude herbal drugs (Chŏpyak), this was substituted with herbal powders that were extracted from each crude herb and mixed with starch or corn powder.

In general, powdered herbal preparations have better safety than crude herbal drugs because they are made at herbal pharmaceutical companies, generally under standardized quality-control conditions. However, the usual form of herbal medication in KM clinics was initially the crude herbal packages, and most patients received it in this form. Powder-type herbal preparations were not familiar to either KM doctors or their patients at KM clinics at that time.

Several reasons were given for the exclusion of crude herbal packages. First, the crude herbal packages were relatively expensive (in the pilot program in 1984, the cost of crude herbal drugs for 1 day was approximately 1 USD or more), and so the insurer had difficulty securing the budget. Second, because of inadequate quality control for the crude herbal drugs, the government preferred herbal preparations, and benchmarked the benefit coverage of Japanese public health insurance in which about 140 formulas with herbal preparations were covered.8 Finally, because the crude herbal packages were the main source of income for KM doctors, the KM society acquiesced the exclusion of crude herbal packages. Because the separation of prescription and dispensing drugs was not yet established, KM doctors could prepare the crude herbal packages by themselves, and could obtain a profit margin from preparing herbal medicines. This was the traditional way of business for KM doctors, and the price of herbal medicines was regarded to include outpatient care cost, prescription cost, and the actual cost of the herbal medicines.

Even though the major method was excluded, KM insurance has since gradually expanded the coverage; the number of notified formulas increased to 56 in 1990, KM test devices such as Yangdorak (Ryodoraku), which is used for detecting excessive or deficient conditions of organs by measuring electrical resistance of the skin,9 and the Pulse diagnosis detector were covered in 1994, and three KM physical therapies were added for coverage in 2009. With respect to the reimbursement structure, the resource-based relative value scale (RBRVS) was introduced for KM health insurance in 2002, providing a methodical approach for fee estimation and the adjustment of balance among KM services and procedures.

3. Current reimbursement scheme and NHI coverage for KM

The general principles of KM reimbursement through the NHI are as follows.10, 11 First of all, outpatient care is reimbursed using the fee for service (FFS) system based on the RBRVS, which was originally developed by Professor Hsiao at Harvard University in the 1980s12, 13 and modified for the Korean NHI by Korean researchers. It was implemented for WM and dental procedures in 2000 and for KM procedures in 2002. In the RBRVS system, the fee for each procedure is calculated by multiplying the relative value (RV) of each procedure or service by a conversion factor (CF), corresponding to a monetary amount per RV score. The RV of each procedure is composed of three separate factors, namely, physician's work, practice expense, and malpractice expense. The factors used to determine physician's work include the time it takes to perform the service, the technical skill and physical effort, the mental effort and judgment required, and stress due to the potential risk to the patient.14 The RV scores are adjusted every 5 years based on research data, and the CF is determined at the fall of each year based on negotiation and contract, in principle, between the National Health Insurance Service (NHIS) and the Association of Korean Oriental Medicine (AKOM). The CF for the year 2013 is 72.5 Korean won (1 KW = 0.065 USD).

Second, an additional fee is applied to each claim depending on the type of medical institution, because the indirect costs may differ according to the size of each type of institution. For university-affiliated hospitals, the markup rate is 25%; that is, the NHI reimburses 125% of the total amount of the fee for a claim. For KM hospitals, the markup rate is 20%, and for KM clinics it is 15%.

Third, for all medical institutions the total reimbursed amount may be partially cut depending on the number of outpatients per day. For example, there is no cutback if one doctor treats 75 or fewer cases of outpatients; however, if one doctor treats over 75 cases, 90% of the total benefit amount is reimbursed for claims up to 100 cases, 75% is reimbursed for up to 150 cases, and 50% is reimbursed for over 150 cases.

Fourth, to prevent patients from experiencing a moral hazard, the Korean NHI applies both co-payment and co-insurance. The guardians of patients under the age of 7 have to pay 21% of the total treatment amount themselves, whereas for patients aged 7–64 years the charge is 30% of the treatment fee. The fee structure is more complicated for patients aged 65 years and over: patients pay 1500 KW (1.3 USD) up to a total treatment amount of 15,000 KW (12.7 USD), and 30% of the total fee if it is over 15,000 KW (if there is a medication, the reference point is raised to 20,000 KW).

Finally, the benefit coverage for KM includes outpatient visits, inpatient care, acupuncture, moxibustion, cupping, medication, diagnostic tests, and other treatments. Table 1 shows the current benefit coverage for KM and RV scores in the NHI program.

Table 1.

KM insurance benefits and RV scores (as of 2012).

| Benefit item | RV score | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Outpatient visit | New patient | 152.06 | |

| Established patient | 95.98 | ||

| Inpatient care | KM hospital | 409.18 | |

| KM clinic | 355.29 | ||

| Dispensing of herbal preparations (1 day)* | 4.47 | ||

| Acupuncture | General acupuncture | 34.41 | |

| Special acupuncture | Acupuncture in the intraorbital cavity | 37.87 | |

| Acupuncture into the intranasal sinus | 37.87 | ||

| Acupuncture in the intraperitoneal cavity | 37.61 | ||

| Acupuncture in the intra-articular joints | 35.84 | ||

| Acupuncture in the intervertebrae spaces | 37.38 | ||

| Penetration acupuncture | 55.49 | ||

| Laser acupuncture | 36.07 | ||

| Electrical stimulation for acupuncture needle | 51.95 | ||

| Moxibustion | Direct type | 73.70 | |

| Indirect type | 30.51 | ||

| Cupping | Cupping only | 45.62 | |

| Cupping with bloodletting | 73.26 | ||

| Pattern identification (Bianjing) | 32.91 | ||

| Diagnostic test | Yangdorak (Ryodoraku) | 39.81 | |

| Pulse diagnosis | 35.81 | ||

| Meridian function test | 52.91 | ||

| Dizziness test | 42.99 | ||

| Personality test | 169.68 | ||

| Dementia test | 301.41 | ||

| Psychotherapy | Individual psychotherapy | 144.65 | |

| Psychiatric personal history taking | 94.59 | ||

| Family psychotherapy | 192.05 | ||

| Physical therapies | Hot pack | 10.32 | |

| Ice pack | 10.32 | ||

| Infrared irradiation | 10.32 | ||

Note. From “Association of Korean Oriental Medicine. Benefit expense of Korean medicine health insurance [Hanbang Gŏngangbohŏm Yoyanggŭpyŏbiyong].” Seoul; 2012.

KM, Korean medicine; RV, relative value.

The costs of 68 single herbal preparations are notified separately.

4. Growth of claims and treatment amounts in KM health insurance

Table 2 lists the number of outpatients according to the Korean Standard Classification of Diseases (KCD). Diseases of the musculoskeletal system are ranked first (52.44%), followed by injury and poisoning (19.56%), diseases with KM names, which are not matched with WM disease classification (7.60%), diseases of the nervous system (4.43%), and diseases of the digestive system (4.24%). Clinically, KM services can cover all disease areas, but it is being used disproportionately to treat musculoskeletal disease.

Table 2.

Number of outpatients relative to disease groups in the NHI (first quarter of 2012).

| KCD code | Disease group | Persons (n) | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| A00-B99 | Infectious and parasitic diseases | 25,986 | 0.11 |

| C00-D48 | Neoplasms | 52,531 | 0.22 |

| D50-D89 | Blood and immunity disorders | 2584 | 0.01 |

| E00-E90 | Endocrine, nutritional, and metabolic diseases | 66,339 | 0.27 |

| F00-F99 | Mental disorders | 191,498 | 0.79 |

| G00-G99 | Diseases of the nervous system | 1,072,377 | 4.43 |

| H00-H95 | Diseases of the sense organs | 235,213 | 0.97 |

| I00-I99 | Diseases of the circulatory system | 215,185 | 0.89 |

| J00-J99 | Diseases of the respiratory system | 823,328 | 3.40 |

| K00-K99 | Diseases of the digestive system | 1,027,035 | 4.24 |

| L00-L99 | Diseases of skin and subcutaneous tissue | 235,633 | 0.97 |

| M00-M99 | Diseases of the musculoskeletal system and connective tissue | 9,706,754 | 52.44 |

| N00-N99 | Diseases of the genitourinary system | 131,730 | 0.54 |

| O00-O99 | Complications of pregnancy, childbirth, and puerperium | 5189 | 0.02 |

| P00-Q99 | Congenital anomalies | 4529 | 0.02 |

| R00-R99 | Signs, symptoms, and ill-defined conditions | 849,867 | 3.51 |

| S00-T99 | Injury and poisoning | 4,740,601 | 19.56 |

| Z00-Z99/U00-U19 | Other reasons for contact with health services | 4040 | 0.02 |

| U50-U98 | Diseases with KM names | 1,841,940 | 7.60 |

| Total | 24,232,359 | 100.00 |

Note. From Electronic Data Interchange Claim System, Health Insurance Review Agency.

KCD, Korean Standard Classification of Diseases; KM, Korean medicine; NHI, National Health Insurance.

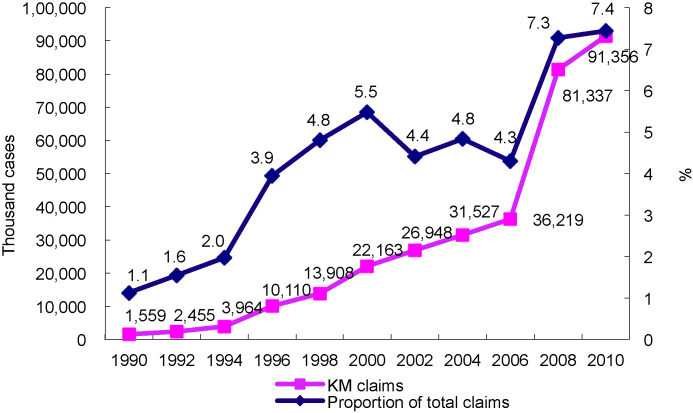

With respect to the number of claims, in 1990 (corresponding to the early stage of KM health insurance) KM represented only 1.1% of the total NHI claims, but this percentage had increased to 7.4% by 2010 (Fig. 1). Claims doubled between 2006 and 2008 not as a result of doubling of patient visits, but rather as a result of the claiming unit changing from per episode to per visit.

Fig. 1.

Number of KM claims from the NHI.

Note. From “National Health Insurance statistical yearbook” (for each year), National Health Insurance Cooperation. KM, Korean medicine; NHI, National Health Insurance.

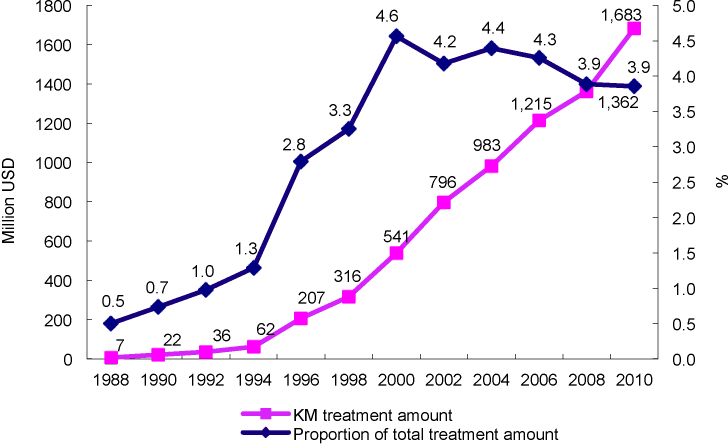

The total expense attributed to KM was just 7,000,000 USD in 1988, but had increased to 1,683,000,000 USD in 2010, representing 3.9% of the total costs of NHI treatments (Fig. 2). If the pharmacy portion is excluded, the KM total expense represented 5.4% of total expense from all medical institutions in 2010. Although the annual treatment amount has increased steadily, the proportion of the total expense has decreased since 2000 as a result of the rapid growth of higher level general hospitals and increase in the number of long-term-care hospitals. The roles of hospitals and clinics have not yet been adequately divided in Korea, and so the growth of hospitals means stagnancy of clinics, and most KM institutions are clinics.

Fig. 2.

Total treatment amounts for KM in the NHI.

Note. From “National Health Insurance statistical yearbook” (for each year), National Health Insurance Cooperation. KM, Korean medicine; NHI, National Health Insurance.

Table 3 gives the percentage distribution of treatment amounts for KM categories at several time points. In the early stages, the largest portion was attributable to outpatient visits, followed by medication. The proportion of the total treatment amount attributable to outpatient visits has slowly decreased over time, but that of medication has plummeted from 27.1% to 1.0% over the past 20 years. By contrast, the proportion attributable to treatments (e.g., acupuncture, moxibustion) has increased sharply to 55.4%. This change in the distribution of treatment amounts per KM category can be attributed mainly to the problem of medication form. This issue is discussed in detail in the “Expanding the Coverage of Herbal Medicines” section. The proportion of claims for inpatient care and diagnostic testing was very small, showing that KM doctors play the main role in the primary care setting.

Table 3.

Percentage distribution of treatment amounts for KM categories under the NHI in Korea between 1990 and 2010.

| Total treatment amount* | Outpatient visit | Inpatient care | Medication | Treatment | Diagnostic test | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1990 | 21,586 | 56.6 | 4.1 | 27.1 | 12.2 | – | 100.0 |

| 1994 | 61,829 | 50.1 | 9.5 | 25.5 | 14.9 | – | 100.0 |

| 2004 | 983,032 | 42.2 | 2.8 | 3.2 | 51.0 | 0.8 | 100.0 |

| 2010 | 1,682,714 | 39.5 | 3.6 | 1.0 | 55.4 | 0.5 | 100.0 |

Data are presented as % unless otherwise indicated.

Note. From “Improvement plan for herbal medicines coverage in KM insurance [Hanbang Ǔryobohŏmŭ Hanyakjejegeupyŏ Gaesŏnbangan],” by B. Lim, 1999, Seoul: Association of Korean Medicine-for the 1990 and 1994 data; “National Health Insurance statistical yearbook,” Health Insurance Review Agency-for the 2004 and 2010 data.

KM, Korean medicine; NHI, National Health Insurance.

Units, thousand USD.

5. Two critical issues on KM insurance

5.1. Expanding the coverage of herbal medicines

Table 3 indicates that the usage of prescribed herbal medications in NHI has reduced dramatically. The primary reason why KM doctors have disregarded the insured herbal preparations is the inconvenience of use and distrust regarding their quality.8 Initially, 68 single herbal preparations and 26 herbal formulas (reference formulas based on the aforementioned 68 insured single herbal medicines) were covered. This means that to be reimbursed for medication for an outpatient, KM doctors must select one of the 26 formulas and fill them with some of the 68 single preparations. The purpose of this single herbal preparation-based coverage was to make the dispensing style similar to the traditional way of crude herbal dispensing in KM clinics. However, other than the reference formulas, KM doctors were unable to compose prescriptions freely, and dispensing single herbal preparations was too cumbersome and time consuming relative to its cheap dispensing fee. Even expansion of the number of formulas to 56 in 1990 provided insufficient reference formulas for KM doctors to treat patients with their various conditions and diseases. Therefore, KM doctors used the uninsured crude herbal packages instead of the insured herbal preparations, which were both more profitable to them and more familiar to the patients.

The quality of the insured herbal preparations was another matter of concern. To produce the single herbal preparation based on the government's standard recipe, each single herbal extract needs to be mixed with diluting agents such as starch or corn powder for granulation. Thus, if a certain formula is filled with several single herbal preparations containing diluting agents, the total amount of diluting agents would be excessive. As a result, the quality of the insured herbal medications would be declined. From the beginning of KM insurance, many patients who took the insured herbal drugs reported indigestion and inefficacy, and KM doctors became increasingly mistrustful of the quality of the insured herbal drugs.8 Another reason for this quality degradation was the fixed cost of the insured herbal preparations. Although NHIS has indicated the price of the insured drugs, cost containment has resulted in the price of herbal preparations being frozen for the past 20 years.

Thus, KM doctors have continued to insist that the NHIS change the herbal coverage from a single-preparation-based form to a formula-based form and expand the number of formulas to about 140, in line with the coverage of the Japanese NHI.8 Although there were some reference formulas in the existing insurance benefit, strictly speaking, the coverage unit was single herbal preparations. If herbal insurance coverage becomes formula based, the use of diluting agents could be reduced significantly by using them only once for each formula. Furthermore, the use of freeze drying in the production process could obviate the need for diluting agents in herbal preparations. Upgrading the quality of herbal preparations and expanding the number of insured formulas may encourage KM doctors to use more insured herbal medicines. However, there have been no effective attempts at herbal insurance reform over the past 10 years.

In 2004, the Ministry of Health and Welfare (MOHW) explored the expansion of coverage for herbal medicines and organized a round table in which representatives from all related interest groups participated, such as government officials on insurance policy, NHIS, the Health Insurance Review Agency, KM doctors, herbal pharmacists, and Western pharmacists. The main issue was the insurance coverage of formula-based herbal preparations. Although most of the participating groups agreed to the coverage expansion of formula preparations, the Western pharmacists demanded, as a preceding condition, the separation of prescription and dispensing for insured herbal preparations, as occurs for WM. Most KM doctors did not accept it for fear that it would be inevitably followed by the separation of crude herbal packages, and the two groups remained firmly opposed on this issue; the MOHW thus put on hold any further discussion in this regard, a status that remains in place to this day.15

This negative stance of the KM community about the separation of the prescription and dispensing of formulas was in part attributable to the historically conflict relationships between KM doctors and Western pharmacists. KM doctors and Western pharmacists have confronted each other over the right to dispense herbs for several decades. KM doctors argued that herbal medicines should be used based on traditional theory and are therefore within the KM doctors’ work boundary, whereas Western pharmacists insisted that because herbal medicines are a type of medicine, only the pharmacists should handle them. KM doctors wanted to ban Western pharmacists from herbal dispensing without a doctor's prescription, but the number of Western pharmacists who prescribed and dispensed herbal medicines was increasing. The herbal dispute (Hanyak Bunjaeng) in 1993 was a symbolic incident involving a clash between the two groups on a national scale.16, 17 As a result of that dispute, the MOHW decided to create a new health profession, herbal pharmacist, to expand the dual health system (KM and WM) to the pharmacy area. However, Western pharmacists were still able to deal in herbal medicines, but with a limited range of 100 formulas.4 This has created a difficult relationship between the two professions, with KM doctors perceiving that Western pharmacists encroach on their profits and that they cannot win any disputes with Western pharmacists. After the implementation of separation of prescription and dispensing of drugs in the field of WM in 2000, Western pharmacists tended to focus on Western drug dispensing, and as a result, herbal medicine sales by Western pharmacists have dropped off sharply. KM doctors have yet to overcome their trauma with Western pharmacists.

5.2. Reforming the reimbursement system

Reform of the reimbursement system has involved two factors: adjustment of the price level and reform of the payment mechanism. When KM was introduced into the NHI plan, the fee for general acupuncture was estimated with reference to that of simple intramuscular injection in the WM fee schedule. Given the technical difficulty involved, it was not considered reasonable that the acupuncture fee should be the same as for a simple intramuscular injection. However, because the baseline price and the annual rate of increase were both low, the fee for general acupuncture has stayed low. The same problem was applied to other procedures; for example, in 1994 the fee for intra-articular acupuncture in KM was the same as for an intra-articular injection in WM, but by 2008 the fee for intra-articular injection has tripled compared with that of intra-articular acupuncture.

With the RBRVS system, the relative balance of prices among KM procedures has improved, but the policy of a fixed total RV score has made it difficult to increase the prices of undervalued KM procedures. In general, procedure split-off has been used to increase prices under the FFS system, but it was not in effect in a system with a fixed total RV score.

The WM community succeeded in increasing the price level for WM procedures using their political capability. A key example is the price raise in the RBRVS system. When RBRVS was first introduced in Korea, the RVs of all WM procedures were estimated, and existing prices were supposed to be adjusted based on these new RVs. However, during the adjustment process, the prices of the undervalued procedures rose, but that of the overvalued procedures did not come down. Consequently, the total price of WM increased despite the fixed total score policy. However, the politically weak KM community failed to increase the total price of KM procedures when the RBRVS was introduced into KM health insurance.

The issue of reforming the payment mechanism of KM insurance has arisen recently while KM doctors were trying to break through the limitation of price adjustment. The NHIS has tried to contain medical expenses, which have grown rapidly by, for example, enhancing the review process to reduce overtreatment, implementing diagnosis-related groups for inpatient care to induce the provider's cost reduction, and providing health check-up programs. More fundamentally, the NHIS considered the implementation of a global budget system, which was proven to effectively contain the medical expenditure.1, 18, 19, 20 Because the physicians’ work might be strongly controlled under a global budget system, WM doctors, who are the most powerful healthcare providers, did not intend to accept this global budget.

The NHIS benchmarked the example of Taiwan, in which a global budget was imposed—in order of size—on dental care in 1998, traditional Chinese medicine in 2000, WM primary care in 2001, and WM hospitals in 2002.1 The NHIS unofficially sounded out the AKOM with a view to accepting the global budget around the year 2008; some of the researchers recommended the global budget to KM doctors and designed an implementation plan.21, 22 However, the AKOM could not accept the NHIS's proposal because the leaders of AKOM could not determine whether or not it was beneficial.

In general, the global budget was not advantageous to medical providers, but it deserved consideration for KM doctors if appropriate incentives for the first implementation could be provided. The recent proportion of KM in the total amount of NHI was 3.9%, and even this rate was in a downtrend. If the NHIS could guarantee over 4% of KM proportion and maintain the rate, it could be a negotiable condition for KM doctors. To accept the global budget could be, for KM doctors, a kind of survival strategy between two powerful groups, that is, the NHIS and Western doctors.

Finally, in 2011, the NHIS and AKOM agreed to organize a committee for reimbursement reform and to start cofunded research on the issue. A final report was submitted the following year, recommending a comprehensive treatment price and a global budget system in KM health insurance.23 The comprehensive treatment price was a kind of partial case payment. At present, each treatment procedure (e.g., acupuncture, moxibustion, and cupping) has its own RV (price), and KM doctors provide one procedure or a combination of two or more procedures. KM doctors are reimbursed at a higher price if they perform more procedures. However, under the comprehensive treatment price system, the new flat price, based on the mean price of typical combinations of acupuncture, moxibustion, and cupping, is reimbursed regardless of quantity or combination of services per visit. Because the comprehensive price system may reduce the management cost of the NHIS, KM doctors can demand a higher treatment price to the level of the saving made by the NHIS. The report also recommended the implementation of a global budget in the area of KM health insurance and suggested the provision of incentives to KM doctors to ease the implementation of that global budget. The suggested incentives were twofold: (1) a guarantee of a fixed proportion of KM expenditure in the total NHI amount and (2) expansion of the KM insurance coverage. The NHIS and AKOM agreed to proceed with negotiation based on the suggestions of the report.

However, the reform of KM reimbursement was put on hold by KM doctors. In 2012, there were severe internal conflicts in the KM community surrounding the countermeasures of the natural novel drug (Chŏnyŏnmulshinyak),4 and mistrust of the existing AKOM leadership has reached a boiling point. This has caused all of the policy driven by that leadership to be denied at an extraordinary KM doctors’ assembly held in late 2012. The future of reimbursement reform of KM insurance remains uncertain.

In conclusion, with the 26 years development, KM insurance system can be regarded as the most advanced model in the world in the aspects of the benefit coverage and the reimbursement scheme for traditional medicine. KM was able to increase the public use and the social influence through public insurance program; however, KM is currently facing challenges due to the public's safety concern and the stagnancy in medical demand.

Three strategies are briefly suggested for the wider use of and quality enhancement of KM service in the NHI. First, the KM community needs to accept the separation of the prescription and dispensing of herbal preparations, and to expand both the quality and quantity of herbal medicine coverage. This can improve the patients’ accessibility to KM and enhance the role of KM doctors as modern medical professionals. Second, in response to the Korean government's stalled reimbursement reform, the comprehensive pricing and global budget for KM health insurance should be positively considered. This could be a survival strategy for KM doctors—who are a minority group—against the political tension that exists between the NHIS and the WM community. Finally, medicine is not a fixed entity, and similarly KM itself is continually changing in various combinations with WM and with other health modalities. The KM community should therefore expand its work area and role by actively accepting the WM diagnostic framework and expanding the sharing area with WM, in a bid to secure the future development of KM.

Conflicts of interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Cheng T.M. Taiwan's new national health insurance program: genesis and experience so far. Health Aff (Millwood) 2003;22:61–76. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.22.3.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lim B., Park J., Han C. Attempts to Utilize and Integrate Traditional Medicine in North Korea. J Altern Complement Med. 2009;15:217–223. doi: 10.1089/acm.2008.0294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Park H.L., Lee H.S., Shin B.C., Liu J.P., Shang Q., Yamashita H. Traditional medicine in China. Korea, and Japan: a brief introduction and comparison Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2012;2012:429103. doi: 10.1155/2012/429103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Na S. East Asian medicine in South Korea. Harv Asia Q. 2012;14:44–56. [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Health Insurance Service. National Health Insurance statistical yearbook. Seoul, Korea: National Health Insurance Service; 1990-2010.

- 6.Yang M.S. Development of National Medical Insurance and Benefit Coverage [Jŏngukmin Ǔiryobohŏmgwa Bohŏmgeupyŏ Gaesŏn Bangan] J Korean Hosp Assoc. 1989;19:42–43. [In Korean] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cho HJ. The quest for professional status: a social and sociological study of Korean traditional medicine in the 20th century. London: Department of Social Policy, London School of Economics and Political Science, University of London; 1999, p. 189.

- 8.Lim B, Choi MS, Lee MJ. Improvement plan for herbal medicines coverage in Korean medicine insurance [Hanbang Ǔryobohŏmŭ Hanyakjejegeupyŏ Gaesŏnbangan]. Seoul, Korea: Association of Korean Oriental Medicine; 1999 [In Korean, English abstract].

- 9.Nakatani Y. Chan's Books and Products; Alhambra: 1972. A guide for application of Ryodoraku autonomous nerve regulatory therapy. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service. Health insurance payment schedule [Gŏngangbohŏm Yoyanggŭpyŏbiyong]. Seoul, Korea: Aram Edit; 2012 [In Korean].

- 11.Association of Korean Medicine. Heath insurance payment schedule for Korean medicine [Hanbang Gŏngangbohŏm Yoyanggŭpyŏbiyong]. Seoul, Korea: Aram Edit; 2012 [In Korean].

- 12.Hsiao W.C., Braun P., Dunn D., Becker E.R. Resource-based relative values. An overview JAMA. 1988;260:2347–2353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hsiao WC, Braun P, Dunn DL, Becker ER, Yntema D, Verrilli DK, et al. An overview of the development and refinement of the Resource-Based Relative Value Scale. The foundation for reform of U.S. physician payment. Med Care 1992; 30:NS1-NS12. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.American Medical Association. Overview of the RBRVS. https://www.ama-assn.org/ama/pub/physician-resources/solutions-managing-your-practice/coding-billing-insurance/medicare/the-resource-based-relative-value-scale/overview-of-rbrvs.page? Published 2013. Accessed March 26, 2013.

- 15.Son C.H., Kim Y.H., Lim S. A study on Korean oriental medical doctors’ use of uninsured herbal extracts and how to promote the insurance coverage of such herbal extracts. J Korean Orient Med. 2009;30:64–78. [In Korean, English abstract] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cho B.H. The politics of herbal drugs in Korea. Soc Sci Med. 2000;51:505–509. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00492-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cho H.J. Traditional medicine, professional monopoly and structural interests: a Korean case. Soc Sci Med. 2000;50:123–135. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00284-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oxley H. Organization for Economic Cooperation & Development; Paris: 1995. New Directions in Health Care Policy. Health Policy Studies; p. p39. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schwartz F., Glennerster H., Saltman R. John Wiley & Sons; Chichester: 1996. Fixing health budgets: experience from Europe and North America. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Etter J.F., Perneger T.V. Health care expenditures after introduction of a gatekeeper and a global budget in a Swiss health insurance plan. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1998;52:370–376. doi: 10.1136/jech.52.6.370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim J., Kim E.H., Kim Y.H. Designing a global budget payment system for oriental medical services in the National Health Insurance. Korean J Orient Prev Med Soc. 2010;14:77–96. [In Korean, English abstract] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ahn TS. Long-term development plan for National Health Insurance payment system [Gŏngangbohŏm Sugajedo Jungjanggi Baljŏn Bangan]. Seoul, Korea: Seoul National University Institute of Management Research; 2011 [In Korean].

- 23.Lim B, Shin BC, Ryu JS, Choi BH, Yoon JW. Rationalization of payment system of National Health Insurance for Korean medicine [Hanbang Gŏngangbohŏm Jibuljedo haprihwa Bangan]. Seoul, Korea: National Health Insurance Service; 2012 [In Korean].