Abstract

Contractile response of a pulmonary artery (PA) to hypoxia (hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction; HPV) is a unique physiological reaction. HPV is beneficial for the optimal distribution of blood flow to differentially ventilated alveolar regions in the lung, thereby preventing systemic hypoxemia. Numerous in vitro studies have been conducted to elucidate the mechanisms underlying HPV. These studies indicate that PA smooth muscle cells (PASMCs) sense lowers the oxygen partial pressure (PO2) and contract under hypoxia. As for the PO2-sensing molecules, a variety of ion channels in PASMCs had been suggested. Nonetheless, the modulator(s) of the ion channels alone cannot mimic HPV in the experiments using PA segments and/or isolated organs. We compared the hypoxic responses of PASMCs, PAs, lung slices, and total lungs using a variety of methods (e.g., patch-clamp technique, isometric contraction measurement, video analysis of precision-cut lung slices, and PA pressure measurement in ventilated/perfused lungs). In this review, the relevant results are compared to provide a comprehensive understanding of HPV. Integration of the influences from surrounding tissues including blood cells as well as the hypoxic regulation of ion channels in PASMCs are indispensable for insights into HPV and other related clinical conditions.

Keywords: hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction, K+ channel, oxygen, patch clamp, pulmonary artery, smooth muscle

1. Introduction

In contrast to the conventional notion that arteries dilate under hypoxia to cope with the metabolic stress in tissues, pulmonary arteries (PAs) show sustained contractile responses under hypoxic conditions in the lungs: this phenomenon is termed “hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction” (HPV). Each branch of bronchi (small bronchi and bronchioles) supplies airflow to a group of alveoli that are perfused by numerous capillaries from PA and arterioles. In fact, the lungs are perfused by the same amount of blood as all the other organs in the human body; pulmonary circulation and systemic circulation are simultaneously driven by the right heart (right atrium and right ventricle) and left heart (left atrium and left ventricle), respectively.

Accidental or pathological occlusion of airways results in collapsed alveoli (atelectasis) and local hypoxia. Blood perfusing the unventilated alveolar area (i.e., unoxygenated blood) converges with normally oxygenated blood in the left heart; this process inevitably lowers the oxygen partial pressure (PO2) in the arterial blood. This results in systemic hypoxia, which is a serious threat that should be prevented in a timely manner. In this respect, HPV is a physiologically important compensatory mechanism for the prevention of a ventilation/perfusion (V/Q) mismatch in the local regions of the lungs, and therefore for protection of humans and animals from systemic hypoxia. In addition, a surgical operation on the lungs requires total collapse of the operated lung (i.e., single-lung ventilation). Owing to HPV responses of the unventilated lung, the operation and anesthetic procedure are performed without obstructing the PA of the operated lung.

Although the physiological responses equivalent to HPV have been described previously, rigorous experimental analysis and deduction of its physiological implications (i.e., prevention of V/Q mismatching) were first performed by von Euler and Liljestrand in 1946.1 Since then, the unique hypoxic constriction of PA has drawn attention of both clinical and basic researchers. In fact, numerous physiological studies have been performed to identify PO2-sensing mechanisms underlying HPV.2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 The putative PO2 sensors and their regulatory factors have been studied at many levels of varied complexity, including perfused lungs, dissected PA rings, and isolated PA smooth muscle cells (PASMCs). The precise understanding, however, is still incomplete, and the suggested molecular mechanisms are a subject of debate.

2. Experimental methods for studying HPV

The ideal physiological condition for observing HPV would be the measurement of PA pressure (PAP) using a catheter in vivo. However, it is very difficult to draw a conclusion regarding a specific hypothesis using the in vivo model with numerous uncontrolled influences from all physiological levels. Therefore, to identify cellular mechanisms of HPV, researchers have opted for in vitro methods using isolated lungs, isolated PAs, and PASMCs.

2.1. HPV studies using isolated lungs

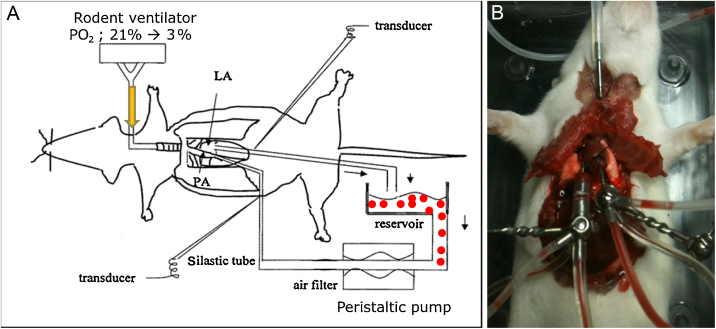

Isolated ventilated/perfused lungs (V/P lungs) are relatively close to the real physiological conditions, and this model provides alveolar hypoxia through tracheal ventilation as well as maintains pulmonary circulation with blood cells while excluding neural and hormonal influences (Fig. 1). In addition to excluding the effects of other organs and their systems, the extent of perfusion and ventilation can be controlled separately in a V/P lung. Because of these advantages, many studies have been performed using the V/P lung method in various species such as sheep, pigs, canines, rabbits, rats, and even mice.7, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16

Fig. 1.

A hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction study using a ventilated/perfused lung model in rodents. (A) A schematic drawing of the experiment. The rodent ventilator is connected to a tracheal cannula, and either normoxic [O2 pressure (PO2), 21%] or hypoxic gas (PO2, 3%) is passed through it. Perfusion of the pulmonary vascular system is achieved using a peristaltic pump connected to the right ventricle (i.e., pulmonary artery; PA) as an inlet and to the left atrium (i.e., pulmonary vein) as an outlet. Our system uses rat or mouse erythrocytes (closed circles in A). PA pressure is measured using a pressure transducer connected to the inlet tubing using a three-way connector. (B) Photo taken during the ventilated/perfused lung experiment in a mouse. LA, left atrium.

A typical experiment involving an isolated V/P lung is conducted as follows: Under deep anesthesia, tracheostomy is performed to establish regular ventilation with a gas mixture containing 21% O2 and 5% CO2. After administering heparin, catheterization of the main PA is performed, and the catheter is connected with a pressure transducer for measurements of PAP. The ascending aorta and PA are sutured together, and then a right ventriculotomy is performed to achieve drainage for pulmonary perfusion. The inclusion of red blood cells in the perfusate is usually helpful for obtaining stable and repetitive HPV responses.15, 16

2.2. HPV studies using an isolated artery segment (arterial ring)

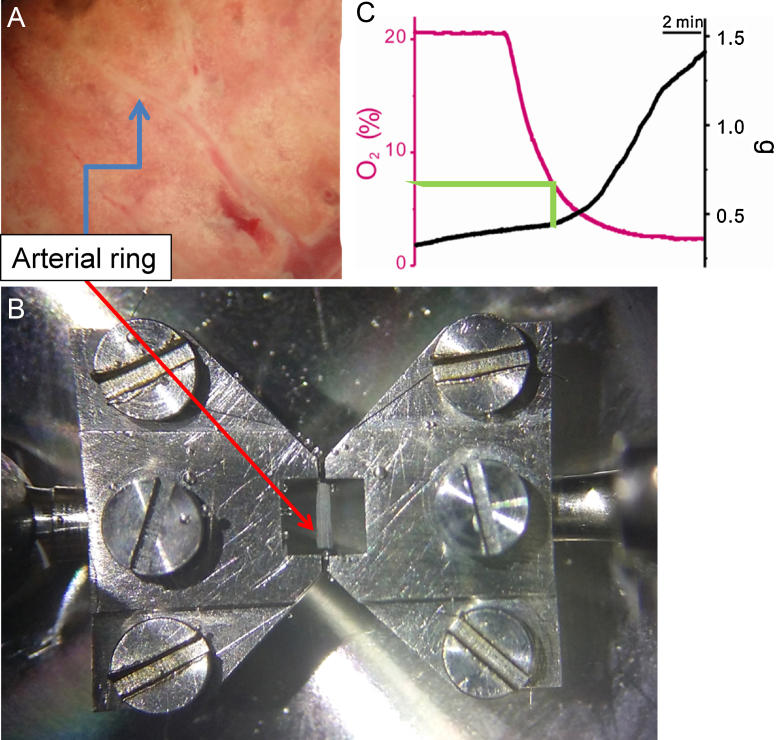

It is generally accepted that HPV is intrinsic to PA; both a sensor and an effector are present in PASMCs. Therefore, theoretically, the measurement of isometric arterial tone should be an objective way to study HPV. It should be noted that hypoxia alone cannot induce HPV in an isolated PA; a partial contraction induced by a vasoactive agonist (a “pretone” agent) is necessary to attain reliable contractions in response to combined hypoxia. It is generally agreed that a variety of locally released intrinsic vasoactive agents (e.g., prostaglandins) are inevitably washed away during dissection of PA, and therefore, these agents should be supplied in an isometric contraction study. While studying HPV on isolated PA (HPV-PA) the precise effects and mechanisms of the pretone condition should also be considered for integrative understating of HPV (see a discussion later). In our case, the third or fourth level of PA segments (diameter, 0.2 mm; length, 3 mm) is assessed using a Mulvany-type myograph (410A; DMT, Aarhus, Denmark) during an HPV-PA study (Fig. 2). The PA rings are mounted using 25-μm tungsten wires, and direct bubbling of a hypoxic gas (3% PO2, 5% CO2, and balanced N2) is used to identify the effects of hypoxia. The endothelial layer of PA is more vulnerable to mechanical damage during the process of wire insertion. The contribution of endothelium to HPV was neglected, as the presence or absence of an intact endothelium does not significantly affect the level of HPV measured using the myograph technique.

Fig. 2.

Isometric contraction measurement using a pulmonary arterial (PA) ring. (A) A view of a rat lung. The third branch of the PA (arrow) was dissected and trimmed under a stereomicroscope. (B) PA rings placed in a Mulvany-type myograph using tungsten wires connected to two jaws (arrow). Although not shown here, the chamber fluid is directly bubbled with either normoxic [O2 pressure (PO2), 21%] or hypoxic (PO2, 3%) gas. (C) A representative recording of simultaneously measured PO2 and PA tone. An incremental change of PA tone (hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction) was discernable at PO2 below 7%.

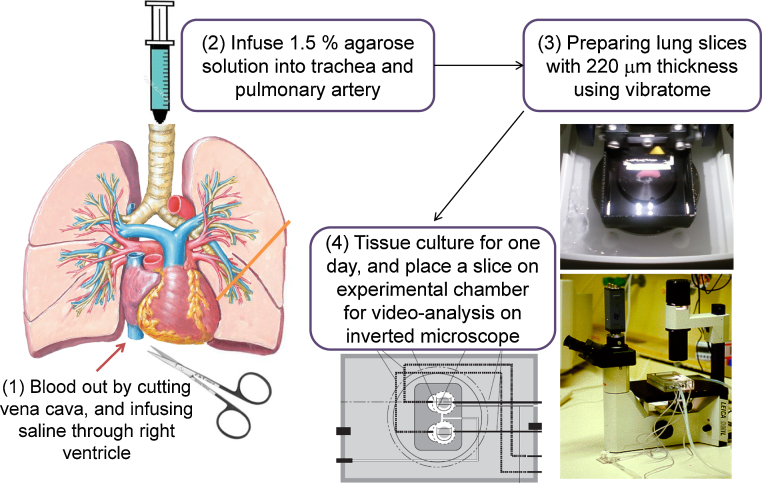

2.3. HPV studies using precision-cut lung slices

Another type of experimental method for measuring PA contractions is morphometric video analysis of PA segments embedded in a thin slice of a lung (Fig. 3). Viable tissue slices of uniform thickness (precision-cut lung slices or PCLSs) have been widely used for neurophysiological research. For a very soft organ like the lung, agarose gel instilling is required to attain appropriate solidity.17 PCLSs can be cultured for 48 hours18, 19, 20 and have been successfully used in pharmacological studies of airway contractility.21, 22, 23, 24, 25 However, there are only a few trials of the PCLS technique, including ours, intended to study HPV and pharmacological responses of PA.20, 26, 27

Fig. 3.

Procedure for the preparation of lung slices (precision-cut lung slices; PCLSs) and video analysis of airway lumens using PCLSs. The PCLS chamber was perfused with a physiological solution enabling drug application and washout. In addition, the temperature of the experimental solutions was maintained using water jacket circulation systems and a semitight cover.

2.4. HPV studies using isolated PASMCs

Among the various molecular mechanisms underlying HPV, explanations involving O2-sensitive ion channels have been the most widely accepted. Therefore, it seems that elucidation of molecular identity of the O2-sensitive channel is the key question. In fact, many previous studies applied electrophysiological methods (e.g., patch-clamp technique) to PASMCs obtained by enzymatic digestion of PA tissues. Just as in other types of smooth muscle cells, membrane depolarization from approximately −60 mV to above −40 mV starts to activate voltage-gated L-type Ca2+ channels (VOCCL) in PASMCs. In this regard, either K+ channel inhibition or nonselective cation (NSC) channel activation is likely to induce membrane depolarization.

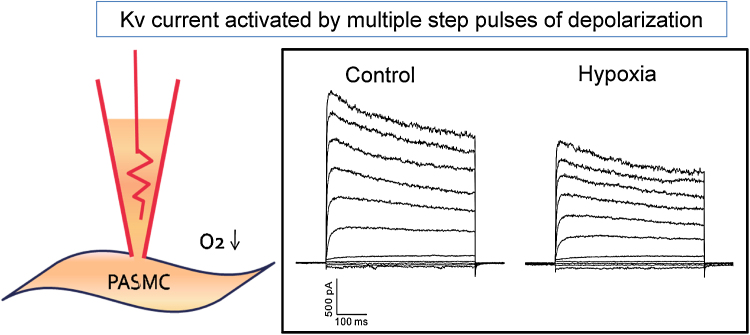

For preparation of isolated myocytes, dissected PAs are digested with collagenase and papain. Then, the softened PAs are gently agitated using a wide-bore fire-polished glass pipette. For patch-clamp experiments, a glass microelectrode with a small tip (diameter < 1 μm) is used for each cell. Patch-clamp amplifiers are commercially available. Either steplike depolarization or ramplike pulses are applied to obtain a current–voltage relationship (I/V curves) of PASMCs. The bath solution is made hypoxic by bubbling it with N2 (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

A schematic drawing of a whole-cell patch-clamp recording and representative traces of membrane currents. Hypoxic perfusate [O2 pressure (PO2), 3%] decreased the amplitude of the outward K+ current (voltage-gated K+ channel current).

PASMC, pulmonary artery smooth muscle cell.

3. Mechanisms of PA contraction and their regulation by hypoxia

3.1. Background

An increase in cytosolic Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]c) is crucial for contraction of smooth muscles. As for the source of the [Ca2+]c increase, both Ca2+ influx through the plasma membrane Ca2+ channels and Ca2+ release from intracellular stores (e.g., sarcoplasmic reticulum) have been proposed, with differential relative contribution depending on the context. Among such models, the Ca2+ influx through VOCCL seems to be the most crucial event. Because VOCCL is activated by depolarization above −40 mV, the membrane depolarization of PASMCs is necessary for HPV. In this regard, the molecular nature of O2-sensitive ion channels determining the membrane potential has been the hot topic during the last decades of HPV research.

Among the proposed hypotheses, hypoxic inhibition of K+ channels has been suggested as an essential O2-sensing mechanism.2, 3, 4, 5, 6 With regard to the subject of O2-sensitive K+ channels in PASMCs, numerous types of K+ channels have been proposed as the K+ channel for HPV. Such diversity is essentially due to the differences among various types of tissues (PA segmental levels) and differences among animal species. Even in a single type of PASMC, at least five different types of K+ channels (see the following discussion) are expressed, and each of them has been studied to determine the extent of O2 sensitivity.

The major types of K+ channels in PASMCs are voltage-gated K+ channels (the Kv subfamily), Ca2+-activated K+ channels (BKCa, maxi-K), two-pore domain K+ channels (the KCNK subfamily channels such as TASK-1), adenosine triphosphate (ATP)-sensitive K+ channels (KATP), and the KCNQ family.4, 5, 28, 29, 30, 31 Among the various types of K+ channels, Kv channels have been the most promising candidates,3, 4, 5, 6 and hypoxic inhibition of a Kv current was also confirmed in one of our studies.32 Hypoxic inhibition of the TASK-type KCNK channel was also suggested in rat PASMCs.28, 32 Nevertheless, the lack of a specific and selective blocker of TASK channels hinders precise evaluation of the contribution to the hypoxic depolarization of PASMCs. The putative functions of BKCa and KATP in the hypoxic depolarization during HPV are generally believed to be minor because specific inhibitors of these channels do not affect HPV.33 Taken together, the aforementioned data suggest that hypoxic inhibition of K+ channel(s) has been suggested as a key event in the electrophysiological model of HPV. The resultant membrane depolarization could activate L-type Ca2+ current, and then pulmonary vasoconstriction is triggered.3, 4, 34, 35 However, it is still debatable whether the hypoxic inhibition of K+ channel is sufficient or is the sole mechanism for inducing membrane depolarization in PASMCs. Different opinions on the molecular nature of O2-sensitive K+ channel are also important issues.

3.2. Debates on the nature of O2-sensitive K+ channels in HPV

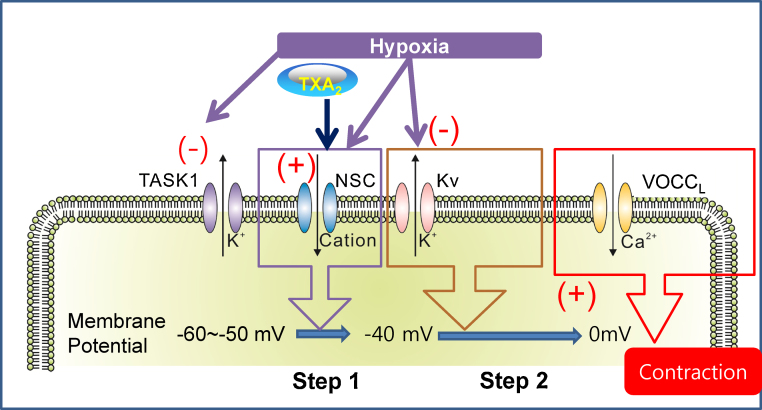

Many researchers applied inhibitors of Kv channels [e.g., 4-aminopyridine (4-AP)] to PAs in order to identify the contribution of the O2-sensitive Kv current to HPV; in other words, 4-AP is used to mimic an HPV-like contraction. However, the response of PA to 4-AP is not consistent with the functional expression of Kv current. A critical question arises because the PA tone is not increased by 4-AP alone, as has been described in our study.32 Such results suggest that the 4-AP-sensitive Kv current is not significantly active in the smooth muscle cells of intact PA. In other words, other types of K+ channels may be involved, that is, those that are active at more negative membrane voltage ranges than the threshold voltage for Kv. In this respect, the so-called background-type K+ channels with two-pore domains (e.g., the TASK subfamily of KCNK channels) may play a role in determining the resting membrane potential of PASMCs. In fact, we and other groups have identified the expression of TASK-like channels in rat PASMCs and their inhibition by hypoxia.28, 36 Nevertheless, as mentioned earlier, a selective blocker of TASK channels is still lacking, which hinders precise evaluation of the contribution of TASK-like channels in HPV. It is requested to consider the hypoxic inhibition of TASK-like K+ channels as one of the initial depolarizing signals for HPV (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

The current model of the cellular mechanism of hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction in a rat pulmonary artery (PA). Relevant ion channels are displayed. Under normoxia, the membrane potential of the smooth muscle of the PA is held at approximately −50 mV because of the TASK-like background current of a K+ channel. Hypoxic conditions initially decrease TASK activity. When combined with TXA2, activation of NSC induces membrane depolarization up to the threshold voltage for activation of Kv channels (Step 1). In addition to the NSC activation, hypoxic inhibition of the Kv current further depolarizes the membrane potential (Step 2). As the membrane potential depolarizes above −40 mV, the activation of VOCCL eventually allows for Ca2+ influx for contraction of smooth muscles.

Kv, voltage-gated K+ channel; NSC, nonselective cation channel; TASK-1, background-type K+ channel with a two-pore domain (K2P); TXA2, thromboxane A2; VOCCL, voltage-gated L-type Ca2+ channels.

Perplexing results are also observed in perfused lungs. Different from the response of isolated PA, the application of 4-AP increases the PAP in rat lungs perfused by physiological salt solution containing blood components. In other words, 4-AP could mimic the HPV in V/P lungs. The divergent results obtained between isolated PA and V/P lungs suggest that some unidentified substances that are released from the tissue (e.g., lung parenchyma) or intrinsic to blood components are necessary for the sensitivity of PA to 4-AP. These data also suggest that hypoxic inhibition of Kv channels alone is not sufficient, and that additional procontractile stimuli seem to be indispensable for HPV. Then the question arises, what are the “pretone” agents responsible and what are the underlying mechanisms?

3.3. Necessity of pretone agents for HPV in an isolated PA

Most previous studies using isolated PAs demonstrate HPV responses in the presence of relatively low concentrations of contractile agents such as thromboxane A2 (TXA2) or prostaglandin F2-alpha (PGF2α).2, 5 One of our studies showed that the application of a small amount of a TXA2 analog alone (U46619, 3–10 nM) induces only a weak contraction (5–10% of the control contraction induced by 80 mM KCl). Nevertheless, pretreatment with a low concentration of U46619 is necessary for HPV.32 Another interesting finding was that 4-AP can evoke a strong contraction of isolated PA with U46619 pretreatment but not in the absence of U46619. Such results suggest that the stimulation of TXA2 receptor has a permissive effect of inducing sufficient depolarization in concert with the Kv inhibition by 4-AP (see the following discussion).

What is the cellular response to TXA2 in PASMCs? According to our recent report, the most likely candidate for the TXA2-activated conductance belongs to the NSC channels.35 Through the activation of NSC channels, TXA2 may induce partial depolarization to the voltage range in which Kv activation can balance further depolarization. Within this mutually balancing range of membrane voltage, VOCCL is not yet activated, or is only minimally activated. When hypoxic conditions are added, the hypoxic inhibition of Kv is expected to allow for significant depolarization that finally induces VOCCL activation, Ca2+ influx, and vasoconstriction (Fig. 5). The pharmacological inhibition of Kv by 4-AP would have similar effects, mimicking hypoxia. According to our recent study using pharmacological inhibitors and reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction analysis, the most likely candidate for the TXA2-activated NSC channel is transient receptor potential cation channel, subfamily V, member 2 in rat PASMCs, which requires further study using genetically modified tissue or animal for the final identification.32

4. Different HPV responses depending on methods

4.1. Necessity of pretone agent for HPV: Isolated PA versus V/P lung

As mentioned in the previous section, pretreatment with TXA2 is required for inducing HPV32 in isolated PAs. By contrast, an HPV study using an isolated V/P lung showed that TXA2 is not necessary for HPV (i.e., for a PAP increase by hypoxia).37 Without any pretone agent, however, HPV of a V/P lung generally shows attenuated responses to repetitive hypoxic challenges.

Pretreatment with angiotensin II enables repetitive and regular HPV in V/P lung experiments.8, 13, 15, 38 In summary, angiotensin II is helpful for augmentation or stabilization of HPV and is not required for initiation of HPV.37 It appears that angiotensin II can also be an effective pretone agent for HPV in an isolated PA. Surprisingly, application of angiotensin II does not induce HPV, whereas angiotensin II by itself induces a prominent and transient contractile response in rat PAs.16 Taken together, the differential responses and the necessity of various pretone agents suggest that angiotensin II can induce a release (from lung parenchymal cells) of more direct pretone agents (e.g., TXA2 and PGF2α) for HPV of PAs.

4.2. Studies of HPV in PCLSs

The V/P lungs are a more physiological model than the dissected PA. Nonetheless, because the circulatory systems are closed, they are difficult and inefficient for various experimental conditions, that is, their experimental flexibility is limited. For these reasons, it has been suggested that the PCLS model might serve as a compromise between the aforementioned two methods because of preservation of the influence of the lung parenchyma and its ability to vary the solution exchange and drugs applied. Furthermore, short-term tissue culture of PCLSs may be used for induction of pathological conditions. Recently, we tested feasibility of the PCLS technique for studies of HPV in terms of the necessity of a specific pretone agent. The results showed that the responses of PA segments embedded in PCLS are closer to the responses of isolated PAs than those of a V/P lung: (1) TXA2 is required for both HPV and 4-AP-induced constriction of PA segments in PCLS and (2) angiotensin II pretreatment is not effective for HPV in PCLS. These observations suggest that in the PCLS model, local vasoactive substances from the parenchymal cells adjacent to PA are insufficient to produce changes in PA. Therefore, it is necessary to use both an isometric tension assay using PA and PAP measurements using a V/P lung for the study of HPV.

4.3. Is TXA2 the intrinsic mediator of HPV in a V/P lung?

Because TXA2 is one of the arachidonic acid (AA) metabolites, it is possible that various AA metabolites may serve as blood-borne modulators of HPV. Furthermore, phospholipase A2 can be activated by hypoxia.39, 40, 41, 42 AA is metabolized through the following three major pathways: (1) cyclooxygenase (TXA2 and prostaglandins such as PGF2α and prostaglandin I2), (2) lipoxygenase (leukotrienes), and (3) cytochrome P450 enzymes (epoxyeicosatrienoic acids and hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acids). Our study using pharmacological antagonists of the receptors of these aforementioned AA metabolites demonstrated that not only TXA2 but also cysteinyl leukotrienes can work as endogenous factors that facilitate HPV in rats. By contrast, the inhibitory effects of the receptor agonists are generally incomplete, suggesting that other intrinsic vasoactive agonists such as purinergic agonists13 may serve as pretone agent(s) in pulmonary circulation.

4.4. Different effects of carbon monoxide on PA and a V/P lung

Both a contractile agent and a relaxing molecule have different effects on HPV in isolated PA and a V/P lung. Endogenous carbon monoxide (CO) is thought to be one of the vasodilatory regulators. Like NO, CO activates soluble guanylate cyclase, and increases production of cyclic guanosine monophosphate in the lungs.43 CO may also cause pulmonary vasodilation by activating BKCa and inducing hyperpolarization. Some researchers have explored the physiological functions of CO in PA or HPV.14, 44, 45, 46, 47 According to our research, application of exogenous CO induces different results in a V/P lung and in PA. In isolated PAs, HPV is completely inhibited by 3% CO. By contrast, CO attenuates HPV of a V/P lung only by 50%.14 It seems that the lung parenchyma may eliminate the inhibitory influence of CO; this effect may be mediated by HPV-related factors in an isolated lung, which are more complex than those in isolated PAs. Some vasoactive molecules might be released from the lung parenchyma and attenuate the relaxing influence of CO.

5. Conclusion and future directions

In this review, we described various methods for measuring HPV and compared recent conflicting experimental findings obtained using different methods. The precise regulatory mechanism and the positive regulator of HPV are still controversial topics. The conflicting experimental results have been occasionally produced with varied experimental designs, methodologies, and species.

Lessons from the studies using isolated PASMCs and PAs can be combined to deduce an electrophysiological model of HPV in a rat PA (Fig. 5). The model already contains a lot of information about multiple types of ion channels, taking into account their voltage dependence and agonist-induced signaling. In fact, even before this experimentally supported model, we proposed virtual simulation of PASMC where the necessity of a depolarizing NSC channel was emphasized.48 These data may serve as a small but significant example of effectiveness of the integrative approach; the virtual model precedes our results described in this review and predicts the TXA2-activated cationic current.14, 15, 16, 32, 37

As summarized in this review, there are many cases and reports demonstrating the vast differences between an isolated tissue and an integrated organ, not to mention the whole organism. For more comprehensive and integrative understanding of the complex physiological responses such as HPV, we believe that it is necessary to conduct higher-level studies and to analyze the conflicting results obtained at the organ level such as a V/P lung. In addition, consideration of anatomical characteristics and physical forces and principles is likely to improve the model, which could eventually be used to advance a clinical understanding of human physiology and pathophysiology.

Conflicts of interest

There are no potential conflicts of interest that could influence the authors’ interpretation of the data.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (Ministry of Science, ICT and Future Planning; NRF Nos. 2011–0017370 and 2012-0000809).

References

- 1.von Euler U.S., Liljestrand G. Observations on the pulmonary arterial blood pressure in the cat. Acta Physiol Scand. 1946;12:301–320. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weir E.K., Archer S.L. The mechanism of acute hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction: the tale of two channels. FASEB J. 1995;9:183–189. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.9.2.7781921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Osipenko O.N., Tate R.J., Gurney A.M. Potential role for kv3.1b channels as oxygen sensors. Circ Res. 2000;86:534–540. doi: 10.1161/01.res.86.5.534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Archer S.L., Wu X.C., Thébaud B., Nsair A., Bonnet S., Tyrrell B. Preferential expression and function of voltage-gated, O2-sensitive K+ channels in resistance pulmonary arteries explains regional heterogeneity in hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction: ionic diversity in smooth muscle cells. Circ Res. 2004;95:308–318. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000137173.42723.fb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mauban JR, Remillard CV, Yuan JX. Hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction: role of ion channels. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2005;98:415-20. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Moudgil R., Michelakis E.D., Archer S.L. The role of K+ channels in determining pulmonary vascular tone, oxygen sensing, cell proliferation, and apoptosis: implications in hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction and pulmonary arterial hypertension. Microcirculation. 2006;13:615–632. doi: 10.1080/10739680600930222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fuchs B., Rupp M., Ghofrani H.A., Schermuly R.T., Seeger W., Grimminger F. Diacylglycerol regulates acute hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction via TRPC6. Respir Res. 2011;12:20. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-12-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pozeg Z.I., Michelakis E.D., McMurtry M.S., Thébaud B., Wu X.C., Dyck J.R. In vivo gene transfer of the O2-sensitive potassium channel Kv1.5 reduces pulmonary hypertension and restores hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction in chronically hypoxic rats. Circulation. 2003;107:2037–2044. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000062688.76508.B3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Drop L.J., Toal K.W., Geffin G.A., OKeefe D.D., Hoaglin D.C., Daggett W.M. Pulmonary vascular responses to hypercalcemia and hypocalcemia in the dog. Anesthesiology. 1989;70:825–836. doi: 10.1097/00000542-198905000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gordon J.B., Hortop J., Hakim T.S. Developmental effects of hypoxia and indomethacin on distribution of vascular resistances in lamb lungs. Pediatr Res. 1989;26:325–329. doi: 10.1203/00006450-198910000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schnader J., Undem B., Peters S.P., Sylvester J.T. Effects of nordihydroguaiuretic acid on sulfidopeptide leukotriene activity and hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction in the isolated sheep lung. Prostaglandins. 1993;46:5–19. doi: 10.1016/0090-6980(93)90058-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nelin L.D., Dawson C.A. The effect of N omega-nitro-l-arginine methylester on hypoxic vasoconstriction in the neonatal pig lung. Pediatr Res. 1993;34:349–353. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199309000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baek E.B., Yoo H.Y., Park S.J., Kim H.S., Kim S.D., Earm Y.E. Luminal ATP-induced contraction of rabbit pulmonary arteries and role of purinoceptors in the regulation of pulmonary arterial pressure. Pflugers Arch. 2008;457:281–291. doi: 10.1007/s00424-008-0536-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yoo H.Y., Park S.J., Bahk J.H., Kim S.J. Inhibition of hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction of rats by carbon monoxide. J Korean Med Sci. 2010;25:1411–1417. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2010.25.10.1411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yoo H.Y., Zeifman A., Ko E.A., Smith K.A., Chen J., Machado R.F. Optimization of isolated perfused/ventilated mouse lung to study hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction. Pulm Circ. 2013;3:396–405. doi: 10.4103/2045-8932.114776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Park S.J., Yoo H.Y., Earm Y.E., Kim S.J., Kim J.K., Kim S.D. Role of arachidonic acid-derived metabolites in the control of pulmonary arterial pressure and hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction in rats. Br J Anaesth. 2011;106:31–37. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeq268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sanderson M.J. Exploring lung physiology in health and disease with lung slices. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2011;24:452–465. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2011.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Struckmann N., Schwering S., Wiegand S., Gschnell A., Yamada M., Kummer W. Role of muscarinic receptor subtypes in the constriction of peripheral airways: studies on receptor-deficient mice. Mol Pharmacol. 2003;64:1444–1451. doi: 10.1124/mol.64.6.1444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moreno L., Perez-Vizcaino F., Harrington L., Faro R., Sturton G., Barnes P.J. Pharmacology of airways and vessels in lung slices in situ: role of endogenous dilator hormones. Respir Res. 2006;7:111. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-7-111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Paddenberg R., König P., Faulhammer P., Goldenberg A., Pfeil U., Kummer W. Hypoxic vasoconstriction of partial muscular intra-acinar pulmonary arteries in murine precision cut lung slices. Respir Res. 2006;7:93. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-7-93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bai Y., Sanderson M.J. Modulation of the Ca2+ sensitivity of airway smooth muscle cells in murine lung slices. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2006;291 doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00494.2005. L208–L21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martin C., Uhlig S., Ullrich V. Cytokine-induced bronchoconstriction in precision-cut lung slices is dependent upon cyclooxygenase-2 and thromboxane receptor activation. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2001;24:139–145. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.24.2.3545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bergner A., Sanderson M.J. Acetylcholine-induced calcium signaling and contraction of airway smooth muscle cells in lung slices. J Gen Physiol. 2002;119:187–198. doi: 10.1085/jgp.119.2.187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brueggemann L.I., Kakad P.P., Love R.B., Solway J., Dowell M.L., Cribbs L.L. Kv7 potassium channels in airway smooth muscle cells: signal transduction intermediates and pharmacological targets for bronchodilator therapy. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2012;302:L120–L132. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00194.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ressmeyer A.R., Larsson A.K., Vollmer E., Dahlèn S.E., Uhlig S., Martin C. Characterisation of guinea pig precision-cut lung slices: comparison with human tissues. Eur Respir J. 2006;28:603–611. doi: 10.1183/09031936.06.00004206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Desireddi J.R., Farrow K.N., Marks J.D., Waypa G.B., Schumacker P.T. Hypoxia increases ROS signaling and cytosolic Ca2+ in pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells of mouse lungs slices. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2010;12:595–602. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Held H.D., Martin C., Uhlig S. Characterization of airway and vascular responses in murine lungs. Br J Pharmacol. 1999;126:1191–1199. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Olschewski A., Li Y., Tang B., Hanze J., Eul B., Bohle R.M. Impact of TASK-1 in human pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells. Circ Res. 2006;98:1072–1080. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000219677.12988.e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nelson M.T., Quayle J.M. Physiological roles and properties of potassium channels in arterial smooth muscle. Am J Physiol. 1995;268:C799–C822. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1995.268.4.C799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yokoshiki H., Sunagawa M., Seki T., Sperelakis N. ATP-sensitive K+ channels in pancreatic, cardiac, and vascular smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol. 1998;274:C25–C37. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1998.274.1.C25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Joshi S., Sedivy V., Hodyc D., Herget J., Gurney A.M. KCNQ modulators reveal a key role for KCNQ potassium channels in regulating the tone of rat pulmonary artery smooth muscle. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2009;329:368–376. doi: 10.1124/jpet.108.147785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yoo H.Y., Park S.J., Seo E.Y., Park K.S., Han J.A., Kim K.S. Role of thromboxane A2-activated nonselective cation channels in hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction of rat. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2012;302:C307–C317. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00153.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Coppock E.A., Martens J.R., Tamkun M.M. Molecular basis of hypoxia-induced pulmonary vasoconstriction: role of voltage-gated K+ channels. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2001;282:L1–L12. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2001.281.1.L1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Osipenko O.N., Evans A.M., Gurney A.M. Regulation of the resting potential of rabbit pulmonary artery myocytes by a low threshold, O2-sensing potassium current. Br J Pharmacol. 1997;120:1461–1470. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sham J.S., Crenshaw B.R., Jr., Deng L.H., Shimoda L.A., Sylvester J.T. Effects of hypoxia in porcine pulmonary arterial myocytes: roles of K(V) channel and endothelin-1. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2000;279:L262–L272. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2000.279.2.L262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gurney A.M., Osipenko O.N., MacMillan D., McFarlane K.M., Tate R.J., Kempsill F.E.J. Two-pore domain K channel, TASK-1, in pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells. Circ Res. 2003;93:957–964. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000099883.68414.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Park S.J., Yoo H.Y., Kim H.J., Kim J.K., Zhang Y.H., Kim S.J. Requirement of pretone by thromboxane A2 for hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction in precision-cut lung slices of rat. Korean J Physiol Pharmacol. 2012;16:59–64. doi: 10.4196/kjpp.2012.16.1.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weigand L., Foxson J., Wang J., Shimoda L.A., Sylvester J.T. Inhibition of hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction by antagonists of store-operated Ca2+ and nonselective cation channels. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2005;289:L5–L13. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00044.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ichinose F., Ullrich R., Sapirstein A., Jones R.C., Bonventre J.V., Serhan C.N. Cytosolic phospholipase A2 in hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction. J Clin Invest. 2002;109:1493–1500. doi: 10.1172/JCI14294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Voelkel N.F., Morganroth M., Feddersen O.C. Potential role of arachidonic acid metabolites in hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction. Chest. 1985;88 doi: 10.1378/chest.88.4_supplement.245s. 245S–8S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gerber J.G., Voelkel N., Nies A.S., McMurtry I.F., Reeves J.T. Moderation of hypoxic vasoconstriction by infused arachidonic acid: role of PGI2. J Appl Physiol Respir Environ Exerc Physiol. 1980;49:107–112. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1980.49.1.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tod M.L., Cassin S. Pressor responses to arachidonic acid in pump-perfused sheep lungs. Prostaglandins Leukot Med. 1986;24:57–68. doi: 10.1016/0262-1746(86)90207-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Naik J.S., Walker B.R. Homogeneous segmental profile of carbon monoxide-mediated pulmonary vasodilation in rats. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2001;281:L1436–L1443. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2001.281.6.L1436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vassalli F., Pierre S., Julien V., Bouckaert Y., Brimioulle S., Naeije R. Inhibition of hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction by carbon monoxide in dogs. Crit Care Med. 2001;29:359–366. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200102000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang F., Kaide J.I., Yang L., Jiang H., Quan S., Kemp R. CO modulates pulmonary vascular response to acute hypoxia: relation to endothelin. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;286:H137–H144. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00678.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Miller M.A., Hales C.A. Role of cytochrome P-450 in alveolar hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction in dogs. J Clin Invest. 1979;64:666–673. doi: 10.1172/JCI109507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tamayo L., López-López J.R., Castañeda J., González C. Carbon monoxide inhibits hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction in rats by a cGMP-independent mechanism. Pflugers Arch. 1997;434:698–704. doi: 10.1007/s004240050454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cha C.Y., Earm K.H., Youm J.B., Baek E.B., Kim S.J., Earm Y.E. Electrophysiological modelling of pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells in the rabbits—special consideration to the generation of hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2008;96:399–420. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2007.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]