Abstract

Objectives: To investigate the effects of different nitrate sources on the uptake, transport, and distribution of molybdenum (Mo) between two oilseed rape (Brassica napus L.) cultivars, L0917 and ZS11. Methods: A hydroponic culture experiment was conducted with four nitrate/ammonium (NO3 −:NH4 +) ratios (14:1, 9:6, 7.5:7.5, and 1:14) at a constant nitrogen concentration of 15 mmol/L. We examined Mo concentrations in roots, shoots, xylem and phloem sap, and subcellular fractions of leaves to contrast Mo uptake, transport, and subcellular distribution between ZS11 and L0917. Results: Both the cultivars showed maximum biomass and Mo accumulation at the 7.5:7.5 ratio of NO3 −:NH4 + while those were decreased by the 14:1 and 1:14 treatments. However, the percentages of root Mo (14.8% and 15.0% for L0917 and ZS11, respectively) were low under the 7.5:7.5 treatment, suggesting that the equal NO3 −:NH4 + ratio promoted Mo transportation from root to shoot. The xylem sap Mo concentration and phloem sap Mo accumulation of L0917 were lower than those of ZS11 under the 1:14 treatment, which suggests that higher NO3 −:NH4 + ratio was more beneficial for L0917. On the contrary, a lower NO3 −:NH4 + ratio was more beneficial for ZS11 to transport and remobilize Mo. Furthermore, the Mo concentrations of both the cultivars’ leaf organelles were increased but the Mo accumulations of the cell wall and soluble fraction were reduced significantly under the 14:1 treatment, meaning that more Mo was accumulated in organelles under the highest NO3 −:NH4 + ratio. Conclusions: This investigation demonstrated that the capacities of Mo absorption, transportation and subcellular distribution play an important role in genotype-dependent differences in Mo accumulation under low or high NO3 −:NH4 + ratio conditions.

Keywords: Brassica napus L., Nitrogen source, Transport, Subcellular distribution, Xylem, Phloem

1. Introduction

Molybdenum (Mo) is an essential micronutrient for plant growth and it plays an important role in carbon, sulfur, and nitrogen metabolism, which is mainly via metalloenzymes in plants (Havemeyer et al., 2011; Hille et al., 2011). Generally in China, soils are acidic and poor availability of Mo in soils is widespread (Ye et al., 2011; Cao et al., 2012; Liu et al., 2012), especially in Southeast China (Shi et al., 2006). However, oilseed rape (Brassica napus L.), an important oil crop, is predominantly grown in Mo-deficient soils (Yin et al., 2009). Moreover, oilseed rape requires plenty of nitrogen (N) fertilizer for growth and yield (Behrens et al., 2002; Barłóg and Grzebisz, 2004a; 2004b; Rathke et al., 2006; Leiva-Candia et al., 2013) and Mo deficiency often decreases the activity of nitrate reductase which leads to N deficiency in plants (Chatterjee and Nautiyal, 2001; Ide et al., 2011), poor seedling growth and lower grain yield (Yang et al., 2009; Liu et al., 2010). Furthermore, winter wheat subjected to higher rate of N-fertilization is prone to Mo deficiency (Wang et al., 1999) while supplying NH4NO3 to plants stimulates the remobilization of Mo in black gram (Jongruaysup et al., 1997). Mo plays an important role in the N metabolism of plants, including nitrogen fixation and the transformation of nitrate (NO3 −)-N to ammonium (NH4 +)-N (Kovács et al., 2015). However, little information is available about the Mo uptake, transport, or distribution under different N sources.

NH4 + and NO3 − are two forms of inorganic N available for plant uptake. Studies on NH4 + stress showed that a low NO3 −:NH4 + ratio inhibits plant growth and changes ion balance in the plant (Liu et al., 2014; Babalar et al., 2015; Sokri et al., 2015). Esteban et al. (2016) showed that complementation with nitrate at low doses, which has long been practised in agriculture, can counterbalance the ammonium toxicity in the laboratory. Zhu et al. (2015) reported that the Mo content of Chinese cabbage declined significantly with a decreasing NO3 −:NH4 + ratio. Moreover, the molybdate transporter 1 (CrMOT1) of Chlamy-domonas reinhardtii is activated by nitrate but not by molybdate (Tejada-Jiménez et al., 2007), while molybdate transporter 2 (CrMOT2) is activated by molybdate, but not by the N source (Tejada-Jiménez et al., 2011). The responses of plants particularly of different cultivars to variable NO3 −:NH4 + ratios are still not well known. In this study, we evaluated the variations in Mo uptake, transport, and distribution between two B. napus genotypes treated with different NO3 −:NH4 + ratios under hydroponic culture, mainly by tissue Mo, sap flow and subcellular Mo concentrations.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Plants and growth conditions

Seeds of oilseed rape cultivars ZS11 (high Mo accumulating cultivar) and L0917 (low Mo accumulating cultivar) were sterilized with 10% (v/v) NaClO for 30 min and washed by deionized water for 5–10 min. The sterilized seeds were cold-treated at 4 °C for 2 d and then were germinated on moistened gauze that was fixed to a black plastic tray filled with deionized water at room temperature. After one week, 15 uniform seedlings were transferred to black polyethylene boxes containing 10 L 1/2-strength modified Hoagland solution for 6 d and subsequently full-strength solution. The modified Hoagland solution contains 4 mmol/L Ca(NO3)2·4H2O, 6 mmol/L KNO3, 1 mmol/L NH4H2PO4, 2 mmol/L MgSO4·7H2O, 46.2 μmol/L H3BO3, 9.1 μmol/L MnCl2·4H2O, 0.8 μmol/L ZnSO4·7H2O, 0.3 μmol/L CuSO4·5H2O, 100 μmol/L EDTA-Fe, and 1 μmol/L (NH4)6Mo7O24·4H2O. After 20 d, the seedlings were treated with four different NO3 −:NH4 + ratios with four replications. Plants were cultured in primary solution (NO3 −:NH4 + 14:1) or in primary solution with NH4Cl (NO3 −:NH4 + 9:6, 7.5:7.5, 1:14) according to Nimptsch and Pflugmacher (2007). The pH of solutions was adjusted to 6.5±0.2 with 1 mol/L NaOH. The solutions were renewed every 4 d during the 35-d experiment. At the end of the experiment, plants were harvested and separated into fresh samples (leaves immediately frozen in dry ice and kept frozen until use) and dry samples (roots, stems and leaves were dried at 80 °C until a constant weight was achieved). Meanwhile, xylem sap and phloem sap were collected.

2.2. Exudation techniques

The xylem sap was collected by the method described by Ueno et al. (2011) and Wu et al. (2015). Briefly, plant shoots (two plants) were cut at 3 cm above the roots and the xylem sap was collected from the cut surface by the root pressure method (the initial 1–2 μl of exudates were discarded). The volume of xylem sap was recorded and 4 ml xylem sap was placed in a 50-ml volumetric flask and dried on a hot plate for Mo determination. The phloem sap was collected as described by Tetyuk et al. (2013). Shoots were incubated in a conical flask filled with 65 ml 25 mmol/L EDTA-Na2 in a growth chamber for 24 h at 20 °C and 95% humidity in dark. The collected solution was dried on a hot plate for Mo determination.

2.3. Cell wall, organelle and vacuole isolation

The frozen plant fresh leaves (1 g) were homogenized and the subcellular fractions were separated according to Su et al. (2014) and Li et al. (2016). Each plant sample was homogenized in 12-ml precooled extraction buffer containing 250 mmol/L sugar, 50 mmol/L Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 1 mmol/L MgCl2, and 10 mmol/L cysteine using a chilled mortar and pestle. The mixture was centrifuged at 2057g for 10 min with a refrigerated centrifuge (Eppendorf 5810 R, Germany), and the precipitate was designated as the cell wall fraction mainly consisting of cell walls and cell wall debris. The supernatant was recentrifuged at 12 857g for 50 min, and the precipitate was designated as the organelle fraction which consisted of membrane and organelle components, and the resultant supernatant solution is referred to as the soluble fraction which mainly includes vacuoles and cytoplasm. All the above mentioned steps were performed at 4 °C.

2.4. Mo determination

Plant materials and dried xylem and phloem sap samples were digested with HNO3/HClO4 (4:1, v/v) mixture at 190 °C for 2 h and then at 205 °C. The samples were then dissolved in 10 ml water, and Mo concentration (C Mo) was determined using a graphite furnace atomic absorption spectrometer (Z-2000 series, Hitachi, Japan) method (Nie et al., 2014). The translocation factor (TF) is calculated by C Mo in leaf/C Mo in stalk or C Mo in stalk/C Mo in root, and Mo accumulation is calculated by C Mo×weight of dry matter.

2.5. Statistical analysis

Data were statistically analyzed using SPSS 13.0. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with a least significance difference (LSD) test was performed to analyze the significant differences between treatments (P<0.05). Data were presented as mean±standard error (SE) and Sigma Plot v12.0 was used for the graphs.

3. Results

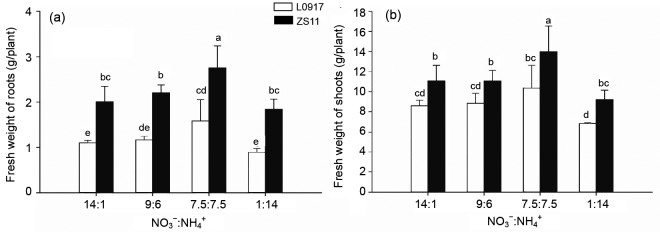

3.1. Biomass

All the biomass (fresh weight (FW)) of roots and shoots of the two rape cultivars reached a maximum at the 7.5:7.5 ratio, but they declined to a minimum at the ratio of 1:14 (Fig. 1). The biomass decreased by 43.8% and 33.9% for cultivar L0917 and by 33.5% and 34.0% for cultivar ZS11 for roots and shoots, respectively, by changing the ratio from 7.5:7.5 to 1:14. The average biomass of cultivar ZS11 roots and shoots was 1.86 and 1.31 times higher than that of cultivar L0917, respectively. This suggests that the two rape cultivars produce the highest biomass under the same concentrations of NH4 + and NO3 −, but a higher proportion of NH4 + results in significant diminution of the biomass of both cultivars particularly the root biomass of L0917 (P<0.05). The high Mo accumulator ZS11 not only had the higher biomass but also had less growth inhibition at the 1:14 ratio than the low Mo accumulator L0917.

Fig. 1.

Fresh weights of roots (a) and shoots (b) at different NO3 −:NH4 + ratios in hydroponic culture

Data were presented as mean±SE (n=4). Different letters above the bar mean significant differences at P<0.05 by LSD-test

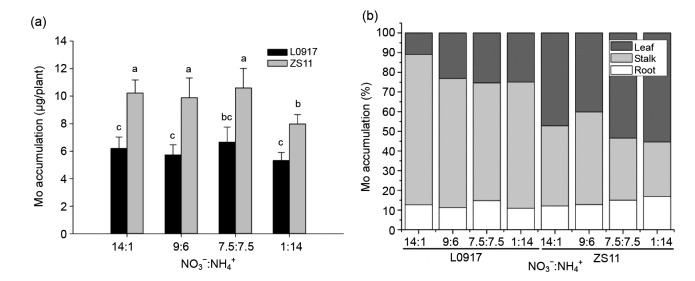

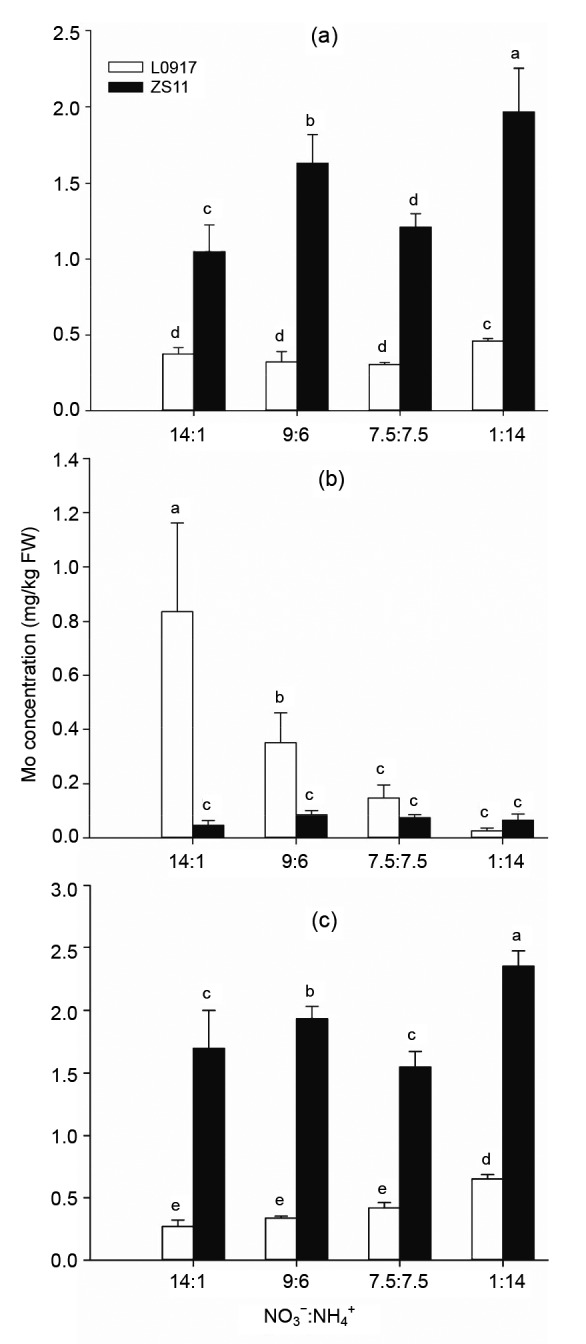

3.2. Mo distribution in tissues

Mo accumulation by both cultivars reached a maximum at the 7.5:7.5 ratio, while the high Mo accumulator ZS11 exhibited a 24.8% (P<0.05) decrease in Mo accumulation at the 1:14 ratio (Fig. 2a), suggesting that high NH4 + inhibited Mo accumulation in the plant. The accumulation percentages of Mo by L0917 were 12.4%, 66.6%, and 21.0% in roots, stalks and leaves, respectively, while these were respectively 14.2%, 36.8%, and 49.0% by ZS11 (Fig. 2b), suggesting that the majority of Mo occurs in the stalks of L0917 and the leaves of ZS11. The proportion of Mo in leaves of both cultivars was increased with the decreasing NO3 −:NH4 + ratio, but the proportion of Mo in stalks decreased under the same conditions.

Fig. 2.

Total plant Mo accumulations (a) and tissue Mo accumulation percentages (b) at different NO3 −:NH4 + ratios in hydroponic culture

Data were presented as mean±SE (n=4). Different letters above the bar mean significant differences at P<0.05 by LSD-test

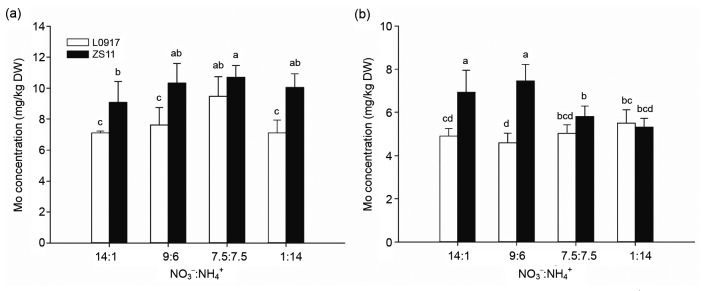

The root Mo concentrations of both the cultivars treated with the 7.5:7.5 ratio were higher than those under the other ratios (Fig. 3a). However, Mo concentrations of L0917 shoots showed no significant difference among the NO3 −:NH4 + ratios, while Mo concentrations of ZS11 significantly decreased with decreasing NO3 −:NH4 + (Fig. 3b). Root and shoot Mo concentrations were higher in cultivar ZS11 than in cultivar L0917 at all treatments. The shoot/root Mo TFs of cultivar L0917 initially declined with the decreasing NO3 −:NH4 + but then increased to the highest value under the 1:14 treatment. The TFs of cultivar ZS11 decreased with the decreasing NO3 −:NH4 + ratio (Fig. 4). The results indicated that Mo concentrations of the roots of both cultivars have the same absorption tendency treated with NO3 −:NH4 + ratios, while Mo transportation from roots to shoots was inhibited particularly in cultivar ZS11.

Fig. 3.

Mo concentrations in roots (a) and shoots (b) of oilseed rape grown at different NO3 −:NH4 + ratios in hydroponic culture

Data were presented as mean±SE (n=4). Different letters above the bar mean significant differences at P<0.05 by LSD-test

Fig. 4.

Mo translocation factors (TFs) for shoot/root of L0917 (a) and ZS11 (b) at different NO3 −:NH4 + ratios in hydroponic culture

Data were presented as mean±SE (n=4). Different letters above the bar mean significant differences at P<0.05 by LSD-test

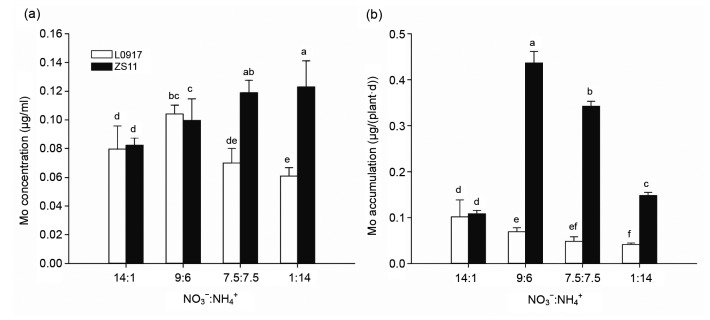

3.3. Mo transport in xylem and phloem

Mo contents of xylem and phloem sap were measured to further study the effects of NO3 −:NH4 + ratio on Mo transport in the oilseed rape (Fig. 5). The Mo concentration in xylem sap of L0917 decreased by 23.40% (P<0.05) but that of ZS11 increased by 49.65% (P<0.05) at the ratio of 1:14 as compared to 14:1. Similarly, Mo accumulation in phloem sap of cultivar L0917 decreased by 59.48% (P<0.05) when the NO3 −:NH4 + ratio was decreased from 14:1 to 1:14. However, phloem sap Mo accumulation in ZS11 increased to a maximum at the ratio of 9:6 before decreasing again with a further reduction in the NO3 −:NH4 + ratio. At the ratio of 1:14, the phloem sap Mo accumulation was 36.78% (P<0.05) higher than that at 14:1. The Mo concentrations and accumulations in xylem and phloem sap of ZS11 were 2.02-and 3.59-fold (P<0.05) higher than those of L0917, respectively. These results showed that ZS11 exhibits notably higher Mo loads in the xylem and phloem transport systems than L0917. In particular, Mo transport in xylem sap of L0917 was inhibited while that of ZS11 was considerably promoted by a low NO3 −:NH4 + ratio or higher NH4 + concentration.

Fig. 5.

Mo concentration in xylem sap (a) and Mo accumulation in phloem sap (b) of oilseed rape grown at different NO3 −:NH4 + ratios in hydroponic culture

Data were presented as mean±SE (n=4). Different letters above the bar mean significant differences at P<0.05 by LSD-test

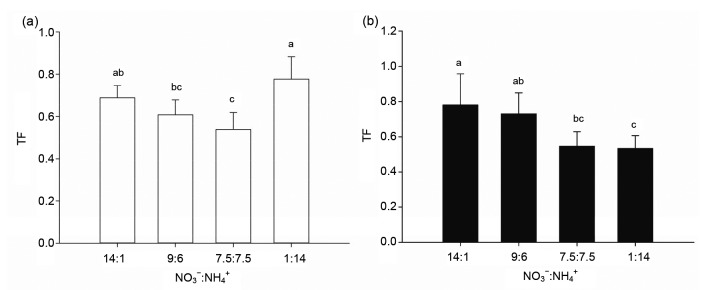

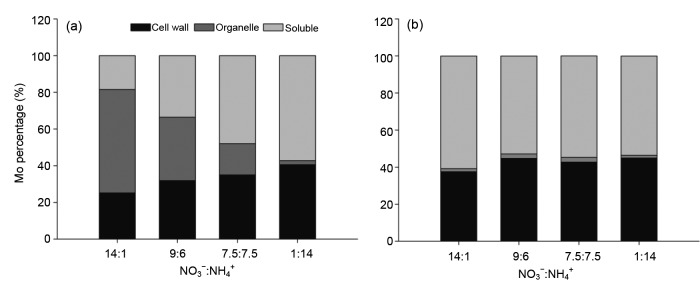

3.4. Subcellular Mo distribution in leaves

Mo concentrations and Mo percentages in subcellular fractions of leaves under different treatments are shown in Figs. 6 and 7. Mo concentrations in cell wall fractions and soluble fractions of both the cultivars under the 1:14 ratio were higher than those under other ratios (Figs. 6a and 6c). In contrast, the Mo concentration in the organelle fraction of L0917 under the 14:1 ratio was 33 times higher than that under the 1:14 ratio (P<0.05), while there was no significant difference in the organelle Mo concentrations of the ZS11 cultivar among the treatments (Fig. 6b). Overall, the average Mo concentrations of both cultivars in the cell wall, organelle, and soluble fractions were 0.915, 0.204, and 1.151 mg/kg, respectively. The percentages of Mo in the organelle fraction of both cultivars were at a minimum with the 1:14 ratio of NO3 −:NH4 + with 2.2% and 1.5% in cultivars L0917 and ZS11, respectively (Fig. 7). The Mo concentrations in the cell wall fractions of leaves of ZS11 were 2.80, 5.05, 3.94, and 4.28 times higher than those of L0917 under the 14:1, 9:6, 7.5:7.5, and 1:14 treatments, respectively. The Mo concentrations in the soluble fractions of leaves of ZS11 were 6.21, 5.67, 3.70, and 3.63 times higher than those of L0917 cultivar under the 14:1, 9:6, 7.5:7.5, and 1:14 treatments, respectively. While the Mo concentration in the organelle fractions of leaves of L0917 were 18.08, 4.05, 2.01, and 0.39 folds higher than those of ZS11 under the 14:1, 9:6, 7.5:7.5, and 1:14 treatments, respectively. These results clearly indicated that more Mo was distributed in cell wall and soluble fractions of ZS11, while Mo distribution in L0917 was much greater in the organelle fractions particularly under high NO3 −:NH4 + ratios. High NO3 −:NH4 + ratios increased the Mo distribution in organelle fractions of L0917, but low NO3 −:NH4 + ratios increased the Mo distribution in cell wall fractions and soluble fractions of both the cultivars.

Fig. 6.

Mo concentrations in cell wall (a), organelle (b), soluble fractions (c) of oilseed rape grown at different NO3 −:NH4 + ratios in hydroponic culture

Data were presented as mean±SE (n=4). Different letters above the bar mean significant differences at P<0.05 by LSD-test

Fig. 7.

Mo percentages in subcellular fractions for L0917 (a) and ZS11 (b) at different NO3 −:NH4 + ratios in hydroponic culture

4. Discussion

In recent years, the understanding with regard to plant responses to the NO3 −:NH4 + ratio has increased, whereas the effects of the ratio on Mo status are still unknown. The significant symptom of higher NH4 + concentrations is the suppression of plant growth (Jampeetong and Brix, 2009). In this work, we found that oilseed rape grows better under a NO3 −:NH4 + ratio of 7.5:7.5 than under 14:1, 9:6 or 1:14. Similar results were reported by Lu et al. (2009) in tomato and Tabatabaei et al. (2008) in strawberry plants, and their results indicated that combined application of NO3 − and NH4 + significantly enhanced the biomass as compared to sole application of either form of N. Compared with the 7.5:7.5 ratio, the decrease in biomass of L0917 cultivar at the 1:14 ratio was greater than that of ZS11 cultivar, indicating that the high Mo accumulating cultivar ZS11 had a better resistance to NH4 + stress. Therefore, combined and particularly equal applications of NO3 − and NH4 + were the most beneficial to both oilseed rape cultivars and the low Mo accumulator cultivar L0917 was more sensitive to higher concentration of NH4 +.

Although the uptake mechanisms underlying ammonium inhibition are not fully understood, previous studies have found that the uptake of many inorganic cations (K+, Mg2+, Ca2+) is reduced under NH4 + nutrition and consequent changes in plant ion balance (Britto and Kronzucker, 2002; Dickson et al., 2016). There is evidence that the effects of NH4 + nutrition are predominantly upon root growth and compete with or pass through the same protein channels (Li et al., 2010; Zheng et al., 2015). In the present study, on two oilseed rape cultivars, Mo accumulation was only decreased under the NO3 −:NH4 + ratio of 1:14 (Fig. 2), suggesting that higher NH4 + concentrations restrain Mo absorption in oilseed rape. Similarly, Zhu et al. (2015) reported that shoot Mo contents were decreased significantly with a decreasing NO3 −:NH4 + ratio at 15 mmol/L N on Chinese cabbage. The percentages of Mo accumulated in the roots of both oilseed rape cultivars increased, whereas the shoot Mo concentrations and the shoot/root TFs for cultivar ZS11 decreased with decreasing NO3 −:NH4 + ratio, suggesting that Mo transport from root to shoot was inhibited by decreasing NO3 −:NH4 + ratio. The Mo accumulation of ZS11 was respectively 64.9%, 72.2%, 59.2%, and 49.6% higher than that of L0917 at the 14:1, 9:6, 7.5:7.5, and 1:14 treatments. Therefore, it is probable that efficient xylem loadings play an important role in shoot mineral accumulation (Ueno et al., 2011; Wu et al., 2015) and phloem is a good indicator for the nutritional conditions in leaves (Peuke, 2010). Yu et al. (2002) also reported that higher phloem mobility was a key factor for leaf Mo accumulation. The present study suggested that at low NO3 −:NH4 + ratios Mo concentrations in xylem and phloem sap of ZS11 were all higher than those of L0917. These results also suggested that ZS11 exhibited a higher Mo transport in xylem, as well as an enhanced ability for remobilization of Mo through phloem transport. Jongruaysup et al. (1994; 1997) also explained that variability of Mo mobility in phloem was found in Mo-adequate plants and NH4NO3 stimulated the remobilization of Mo in the tissues. Therefore, the high Mo concentrations in xylem and phloem sap indicate good uptake in the root and well-supplied leaves.

Compartmentalization of Mo is vital for Mo homeostasis in plant cells. The average Mo concentrations in the cell wall, organelle and soluble fractions of leaves of the two rapeseed cultivars across the four treatments were 0.366, 0.204, and 1.151 mg/kg respectively (Fig. 6). The percentages of Mo in cell wall and solution fractions for L0917 were increased but in the organelle fraction were decreased with decreasing NO3 −:NH4 + ratios. It also appears that Mo was mostly accumulated firstly by the soluble fraction and then by the cell wall, which could be a good reason why the high NO3 −:NH4 + ratio was toxic to organelle and cell wall fractions (Küpper et al., 1999; Hale et al., 2001; Britto and Kronzucker, 2002; Zhao et al., 2015). Plant cell wall binding and soluble fractions are the important mechanisms for metal accumulation (Li et al., 2006; Fu et al., 2011). We showed that the higher Mo accumulator ZS11 distributed more Mo firstly in the soluble fractions and secondly in the cell wall than cultivar L0917. It could be accordingly concluded that the soluble fraction in the high accumulation cultivar is more inclined to retain Mo than that in the low accumulation cultivar. Low NO3 −:NH4 + ratio sharply decreased the Mo distribution in the organelle fractions of L0917, indicating that organelle damage could be the integrated effect of NH4 + excess. This could also be associated with the biosynthesis of the Mo cofactor which is localized in the cytosol (Mendel, 2011).

In conclusion, this study indicated that the two rapeseed cultivars produced more biomass and accumulated more Mo while the nitrogen was supplied at the NO3 −:NH4 + ratio of 7.5:7.5, and the Mo uptake and Mo transport from roots to shoots were inhibited by low NO3 −:NH4 + ratios or higher NH4 +. The high Mo accumulator ZS11 not only exhibited higher Mo concentrations in all the tissues, cell-organs, xylem and phloem sap, but also accumulated more Mo firstly in the soluble fraction and secondly in the cell wall than L0917.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Ron MCLAREN (Emeritus Professor of Environment Soil Science, Lincoln University, New Zealand) and Mr. Dawood Anser SAEED (College of Horticulture and Forestry Sciences, Huazhong Agricultural University, China) for critical reviewing and revision of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Project supported by the National Key Technologies R&D Program of China (No. 2014BAD14B02) and the “948” Project of the Ministry of Agriculture, China (Nos. 2016-X41 and 2015-Z34)

Compliance with ethics guidelines: Shi-yu QIN, Xue-cheng SUN, Cheng-xiao HU, Qi-ling TAN, and Xiao-hu ZHAO declare that they have no conflict of interest.

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

References

- 1.Babalar M, Sokri SM, Lesani H, et al. Effects of nitrate:ammonium ratios on vegetative growth and mineral element composition in leaves of apple. J Plant Nutr. 2015;38(14):2247–2258. doi: 10.1080/01904167.2014.964365. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barłóg P, Grzebisz W. Effect of timing and nitrogen fertilizer application on winter oilseed rape (Brassica napus L.). I. Growth dynamics and seed yield. J Agron Crop Sci. 2004;190(5):305–313. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-037X.2004.00108.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barłóg P, Grzebisz W. Effect of timing and nitrogen fertilizer application on winter oilseed rape (Brassica napus L.). II. Nitrogen uptake dynamics and fertilizer efficiency. J Agron Crop Sci. 2004;190(5):314–323. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-037X.2004.00109.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Behrens T, Horst WJ, Wiesler F. Effect of rate, timing and form of nitrogen application on yield formation and nitrogen balance in oilseed rape production. In: Horst WJ, Schenk MK, Bürkert A, et al., editors. Plant Nutrition. Springer Netherlands; 2002. pp. 800–801. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Britto DT, Kronzucker HJ. NH4 + toxicity in higher plants: a critical review. J Plant Physiol. 2002;159(6):567–584. doi: 10.1078/0176-1617-0774. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cao Q, Zhao C, Qin J, et al. Analysis on content of soil-available molybdenum and its influencing factors in some plantations in Hainan rubber planting areas. J Southern Agric. 2012;43(10):1514–1517. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chatterjee C, Nautiyal N. Molybdenum stress affects viability and vigor of wheat seeds. J Plant Nutr. 2001;24(9):1377–1386. doi: 10.1081/PLN-100106988. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dickson RW, Fisher PR, Argo WR, et al. Solution ammonium:nitrate ratio and cation/anion uptake affect acidity or basicity with floriculture species in hydroponics. Sci Hortic. 2016;200:36–44. doi: 10.1016/j.scienta.2015.12.034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Esteban R, Ariz I, Cruz C, et al. Review: mechanisms of ammonium toxicity and the quest for tolerance. Plant Sci. 2016;248:92–101. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2016.04008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fu X, Dou C, Chen Y, et al. Subcellular distribution and chemical forms of cadmium in Phytolacca americana L. J Hazard Mater. 2011;186(1):103–107. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2010.10.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hale KL, McGrath SP, Lombi E, et al. Molybdenum sequestration in Brassica species. A role for anthocyanins? Plant Physiol. 2001;126(4):1391–1402. doi: 10.1104/pp.126.4.1391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Havemeyer A, Lang J, Clement B. The fourth mammalian molybdenum enzyme mARC: current state of research. Drug Metab Rev. 2011;43(4):524–539. doi: 10.3109/03602532.2011.608682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hille R, Nishino T, Bittner F. Molybdenum enzymes in higher organisms. Coordin Chem Rev. 2011;255(9-10):1179–1205. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.11.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ide Y, Kusano M, Oikawa A, et al. Effects of molybdenum deficiency and defects in molybdate transporter MOT1 on transcript accumulation and nitrogen/sulphur metabolism in Arabidopsis thaliana . J Exp Bot. 2011;62(4):1483–1497. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erq345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jampeetong A, Brix H. Effects of NH4 + concentration on growth, morphology and NH4 + uptake kinetics of Salvinia natans . Ecol Eng. 2009;35(5):695–702. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoleng.2008.11.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jongruaysup S, Dell B, Bell RW. Distribution and redistribution of molybdenum in black gram (Vigna mungo L. Hepper) in relation to molybdenum supply. Ann Bot. 1994;73(2):161–167. doi: 10.1006/anbo.1994.1019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jongruaysup S, Dell B, Bell RW, et al. Effect of molybdenum and inorganic nitrogen on molybdenum redistribution in black gram (Vigna mungo L. Hepper) with particular reference to seed fill. Ann Bot. 1997;79(1):67–74. doi: 10.1006/anbo.1996.0304. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kovács B, Puskás-Preszner A, Huzsvai L, et al. Effect of molybdenum treatment on molybdenum concentration and nitrate reduction in maize seedlings. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2015;96(6):38–44. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2015.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Küpper H, Zhao FJ, McGrath SP. Cellular com-partmentation of zinc in leaves of the hyper-accumulator Thlaspi caerulescens . Plant Physiol. 1999;119(1):305–312. doi: 10.1104/pp.119.1.305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leiva-Candia DE, Ruz-Ruiz MF, Pinzi S, et al. Influence of nitrogen fertilization on physical and chemical properties of fatty acid methyl esters from Brassica napus oil. Fuel. 2013;111(3):865–871. doi: 10.1016/j.fuel.2013.04.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li Q, Li BH, Kronzucker HJ, et al. Root growth inhibition by NH4 + in Arabidopsis is mediated by the root tip and is linked to NH4 + efflux and GMPase activity. Plant Cell Environ. 2010;33(9):1529–1542. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2010.02162.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li TQ, Yang XE, Yang JY, et al. Zn accumulation and subcellular distribution in the Zn hyperaccumulator Sedum alfredii Hance. Pedosphere. 2006;16(5):616–623. doi: 10.1016/S1002-0160(06)60095-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li Y, Zhou C, Huang M, et al. Lead tolerance mechanism in Conyza canadensis: subcellular distribution, ultrastructure, antioxidative defense system, and phytochelatins. J Plant Res. 2016;129(2):251–262. doi: 10.1007/s10265-015-0776-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu G, La G, Li Z, et al. Evaluation of available micronutrient contents in tobacco planting soils in Bijie. Chinese Tobacco Sci. 2012;33(3):23–27. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu H, Hu C, Sun X, et al. Interactive effects of molybdenum and phosphorus fertilizers on photosynthetic characteristics of seedlings and grain yield of Brassica napus . Plant Soil. 2010;326(1):345–353. doi: 10.1007/s11104-009-0014-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu N, Zhang L, Meng X, et al. Effect of nitrate/ammonium ratios on growth, root morphology and nutrient elements uptake of watermelon (Citrullus lanatus) seedlings. J Plant Nutr. 2014;37(11):1859–1872. doi: 10.1080/01904167.2014.911321. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lu YL, Xu YC, Shen Q, et al. Effects of different nitrogen forms on the growth and cytokinin content in xylem sap of tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill.) seedlings. Plant Soil. 2009;315:67–77. doi: 10.1007/s11104-008-9733-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mendel RR. Cell biology of molybdenum in plants. Plant Cell Rep. 2011;30(10):1787–1797. doi: 10.1007/s00299-011-1100-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nie Z, Hu C, Liu H, et al. Differential expression of molybdenum transport and assimilation genes between two winter wheat cultivars (Triticum aestivum) Plant Physiol Bioch. 2014;82(3):27–33. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2014.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nimptsch J, Pflugmacher S. Ammonia triggers the promotion of oxidative stress in the aquatic macrophyte Myriophyllum mattogrossense . Chemosphere. 2007;66(4):708–714. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2006.07.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Peuke AD. Correlations in concentrations, xylem and phloem flows, and partitioning of elements and ions in intact plants. A summary and statistical re-evaluation of modelling experiments in Ricinus communis . J Exp Bot. 2010;61(3):635–655. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erp352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rathke GW, Behrens T, Diepenbrock W. Integrated nitrogen management strategies to improve seed yield, oil content and nitrogen efficiency of winter oilseed rape (Brassica napus L.): a review. Agric Ecosyst Environ. 2006;117(2-3):80–108. doi: 10.1016/j.agee.2006.04.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shi XZ, Yu DS, Warner ED, et al. Cross-reference system for translating between genetic soil classification of China and soil taxonomy. Soil Sci Soc Am J. 2006;70(1):78–83. doi: 10.2136/sssaj2004.0318. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sokri SM, Babalar M, Barker AV, et al. Fruit quality and nitrogen, potassium, and calcium content of apple as influenced by nitrate: ammonium ratios in tree nutrition. J Plant Nutr. 2015;38(10):1619–1627. doi: 10.1080/01904167.2014.964364. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Su Y, Liu J, Lu Z, et al. Effects of iron deficiency on subcellular distribution and chemical forms of cadmium in peanut roots in relation to its translocation. Environ Exp Bot. 2014;97(1):40–48. doi: 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2013.10.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tabatabaei SJ, Yusefi M, Hajiloo J. Effects of shading and NO3:NH4 ratio on the yield, quality and N metabolism in strawberry. Sci Hortic. 2008;116(3):264–272. doi: 10.1016/j.scienta.2007.12.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tejada-Jiménez M, Llamas Á, Sanz-Luque E, et al. A high-affinity molybdate transporter in eukaryotes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(50):20126–20130. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704646104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tejada-Jiménez M, Galván A, Fernández E. Algae and humans share a molybdate transporter. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(16):6420–6425. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1100700108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tetyuk O, Benning UF, Hoffmann-Benning S. Collection and analysis of Arabidopsis phloem exudates using the EDTA-facilitated method. J Vis Exp. 2013;(80):e51111. doi: 10.3791/51111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ueno D, Koyama E, Yamaji N, et al. Physiological, genetic, and molecular characterization of a high-Cd-accumulating rice cultivar. J Exp Bot. 2011;62(7):2265–2272. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erq383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang ZY, Tang YL, Zhang FS. Effect of molybdenum on growth and nitrate reductase activity of winter wheat seedlings as influenced by temperature and nitrogen treatments. J Plant Nutr. 1999;22(2):387–395. doi: 10.1080/01904169909365636. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wu Z, Zhao X, Sun X, et al. Xylem transport and gene expression play decisive roles in cadmium accumulation in shoots of two oilseed rape cultivars (Brassica napus) Chemosphere. 2015;119:1217–1223. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2014.09.099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yang M, Shi L, Xu F, et al. Effects of B, Mo, Zn, and their interactions on seed yield of rapeseed (Brassica napus L.) Pedosphere. 2009;19(1):53–59. doi: 10.1016/S1002-0160(08)60083-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ye X, Guo Y, Wang G, et al. Investigation and analysis of soil molybdenum in the Tieguanyin tea plantations of Fujian Province. Plant Nutr Fertiliz Sci. 2011;17(6):1372–1378. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yin Y, Wang H, Liao X. Analysis and strategy for 2009 rapeseed industry development in China. Chin J Oil Crop Sci. 2009;31(2):259–262. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yu M, Hu C, Wang Y. Molybdenum efficiency in winter wheat cultivars as related to molybdenum uptake and distribution. Plant Soil. 2002;245(2):287–293. doi: 10.1023/A:1020497728331. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhao YF, Wu JF, Shang D, et al. Subcellular distribution and chemical forms of cadmium in the edible seaweed, Porphyra yezoensis . Food Chem. 2015;168:48–54. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2014.07.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zheng XJ, He K, Kleist T, et al. Anion channel SLAH3 functions in nitrate-dependent alleviation of ammonium toxicity in Arabidopsis . Plant Cell Eviron. 2015;38(3):474–486. doi: 10.1111/pce.12389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhu W, Hu C, Tan Q, et al. Effects of molybdenum application on yield and quality of Chinese cabbages under different ratios of NO3 −-N to NH4 +-N. J Huazhong Agric Univ. 2015;34(4):44–50. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]