Abstract

A large number of previous clinical studies have reported a delayed graft function for brain dead donors, when compared with living relatives or cadaveric organ transplantations. However, there is no accurate method for the quality evaluation of kidneys from brain-dead donors. In the present study, two-dimensional gel electrophoresis and MALDI-TOF MS-based comparative proteomic analysis were conducted to profile the differentially-expressed proteins between brain death and the control group renal tissues. A total of 40 age- and sex-matched rabbits were randomly divided into donation following brain death (DBD) and control groups. Following the induction of brain death via intracranial progressive pressure, the renal function and the morphological alterations were measured 2, 6 and 8 h afterwards. The differentially expressed proteins were detected from renal histological evidence at 6 h following brain death. Although 904±19 protein spots in control groups and 916±25 in DBD groups were identified in the two-dimensional gel electrophoresis, >2-fold alterations were identified by MALDI-TOF MS and searched by NCBI database. The authors successfully acquired five downregulated proteins, these were: Prohibitin (isoform CRA_b), beta-1,3-N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase 1, Annexin A5, superoxide dismutase (mitochondrial) and cytochrome b-c1 complex subunit 1 (mitochondrial precursor). Conversely, the other five upregulated proteins were: PRP38 pre-mRNA processing factor 38 (yeast) domain containing A, calcineurin subunit B type 1, V-type proton ATPase subunit G 1, NADH dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] 1 beta subcomplex subunit 10 and peroxiredoxin-3 (mitochondrial). Immunohistochemical results revealed that the expressions of prohibitin (PHB) were gradually increased in a time-dependent manner. The results indicated that there were alterations in levels of several proteins in the kidneys of those with brain death, even if the primary function and the morphological changes were not obvious. PHB may therefore be a novel biomarker for primary quality evaluation of kidneys from brain-dead donors.

Keywords: proteomics, brain death, kidney, prohibitin

Introduction

Brain dead donors are becoming a major source of organ transplantation in China (1–3). Although the number of kidney transplantations from brain dead donors has markedly increased, the supply of donor kidneys still do not meet requirements (4,5). In addition, the outcome of patients receiving grafts from donation after brain death (DBD) in kidney transplantation is often unoptimistic, which mainly involves delayed graft function, primary non-function, acute rejection following transplantation and high levels of urine creatinine (Cr) following 5 years (6,7).

Furthermore, previous studies reported that the injury to organs from brain dead donors may be related to hemodynamic changes, the release of inflammatory cytokines, apoptosis, consumption of coagulation factors, endocrine and hormonal changes (8–10). The relevant pathophysiological alterations impacted on the quality of brain-dead organ donors and may be the key issues constraining the wide use of organs from brain dead donors (11–14). However, the specific details remain unclear. An accurate method is required urgently in order to evaluate the quality of donor kidneys.

In recent years, mass spectrometry (MS)-based proteomics, which was first introduced for the aim of global characterization of a proteome, including protein expression, structure, modifications, functions and interactions has developed rapidly and its quantitative accuracy has improved dramatically (15). A previous study of the authors has demonstrated the difference in protein expression in livers affected by brain death compared with normal livers and one of the typical downregulated biomarkers in brain death livers the Runt-related transcription factor 1 (RUNX1) (16). Using this previous study, the authors used high-resolution MS-based proteomics to identify differentially expressed proteins and study preliminarily the mechanism of kidney injury induced by brain death.

Materials and methods

Animals

A total of 30 12-week-old male rabbits (weight, 3,000–3500 g; Wuhan Wan Qian Jia He Experimental Animal Breeding Center, Wuhan, China) were randomly divided into two groups: Control (n=15) and the DBD groups (n=15). Each group was further divided into four subgroups, according to the 2, 6 and 8 h time points after brain death (n=5 each). The rabbits were housed in a 12 h light/dark cycle and temperature-controlled environment and had free access to food and water in the Experimental Animal Center of Wuhan University (Wuhan, China). All animal experiments were conducted under institutional guidelines and approved by the Ethical Committee for Animal Care and Use of Wuhan University (Wuhan, China) according to animal protocol.

Establishment of the model of rabbit brain death

Similar to the establishment of a pig brain death model (17), a novel model involving progressive intracranial pressure was established. All rabbits were anesthetized with an injection of 1% pentobarbital sodium (40 mg/kg; Shandong Xinhua Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Zibo, China). The rabbits were placed in a supine position and cannulation of the femoral artery and vein was performed, as was xiphoid separation and tracheal intubation, thus allowing for burr hole and catheter placement. In addition, the animals were maintained during the procedure with the assistance of a biological functional system, a rodent ventilator and an intelligent temperature control instrument (Chengdu Thai Union technology Co. Ltd., Chengdu, China). This allows for several parameters to be quantified, including respiration and heart activity, using a ventilator and electrocardiogram, respectively. The intracranial pressure was gradually increased until brain death occurred.

Renal function measuring

Blood samples were collected from each rabbit at the points of 2, 6 and 8 h following brain death to determine blood urea nitrogen and creatinine levels, quantified by the Beckman Kurt AU680 automatic biochemical analyzer (Beckman Coulter Co., Ltd. Shanghai, China).

Histomorphometrical evaluation

The pathological samples were fixed in paraformaldehyde, embedded in paraffin, sectioned (4 mm thickness), and stained for 5 min with hematoxylin and eosin for examination. A pathologist, who was blind to the experimental groups, analyzed the sections.

Protein extraction and 2-DE proteomics profiling

Protein concentration of the supernatant was measured with the Quanti Pro™ BCA assay kit (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) using 2 mg/ml bovine serum albumin (Beijing Bioco Laibo Technology Co. Ltd., Beijing, China). Samples were de-salted and concentrated with the 2-D Clean-Up kit (cat. no. 80-6484-51; GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Pittsburgh, PA, USA) following manufacturer's instructions, following by dissolving with sample buffer. A total of 150 µg protein from the control groups and those in the 6 h experimental group were mixed with rehydration buffer which was composed of 7 mol/l carbamide, 2 mol/l sulfocarbamide, 4% 3-3-Cholamidopropyldimethylammonio-propanesulfonate, 65 mmol/l dithiothreitol, 0.2% BioLyte and 0.001% bromophenol blue. The mixture was in turn isoelectrically focused at 500 V for 1 h, 1,000 for 1 h, 3,000 V for 1 h and 8,000 V for 9.5 h following rehydration for 12 h at 30 V using Immobiline IPG DryStrips (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) with an Ettan IPGphor Electrophoresis system (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences). IPG strips were applied for 12% SDS-PAGE using a PROTEAN® II xi Cell system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, California, USA) following equilibration for 2×15 min subsequently in the equilibration buffer including 1% dithiothreitol and 4% iodoacetamide. The temperature was maintained at 20°C throughout by use of an external cooler. Following staining with Coomassie Brilliant Blue G-250 solution (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology, Haimen, China), the gels were run overnight using a constant current of 2 mA/gel. Each sample was measured in triplicate.

Gel image acquisition and analysis

The SDS-PAGE gels were scanned by the LabScan software (GE Healthcare Life Sciences,) to get the electron images of 2D gel. The 170–9620 PDQuest Basic 2-D Analysis software (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.) was applied to detect protein spots, subduct background, normalize, match, establish an average gel and compare differences, respectively. A total of 6 2-D electrophoresis (E) maps in three replicates were analyzed by the software and compared to identify differentially-expressed proteins. A protein was considered to be expressed differentially if there was >two-fold difference in the spectral count ratios between the two samples.

Protein identification

Among these exclusive spots identified by 2-DE image analysis, protein components of the 10 most prominent spots were investigated using a 4700 proteomics analyzer (Applied Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The protein spots excised from 2-D gels were subjected to de-staining, washing and in-gel digestion with protease trypsin at 37°C overnight, following the description of Shevchenko et al (18). The digestion was stopped the next morning by adding acetic acid to lower the pH to <6, and the samples were centrifuged at 10,000 × g and 25°C for 20 sec to remove insoluble material. Re-dissolving in 0.5% trifluoroacetic acid, the peptide mixtures were detected by the Voyager-DE STR 4307 MALDI-TOF-MS tandem mass spectrometry (Applied Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The proteins were identified using the Mascot Distiller 2.0 software (Matrix Science Ltd., London, UK). The mass spectra collected in the experiment were analyzed using the Swiss-Prot protein database (19). Protein scores >56 were regarded as significant. The one with the highest score was taken into account, if one spot was matched >1 protein member.

Re-identification of typical proteins by western blot analysis

To further identify the differentially expressed proteins, three typical differential proteins named prohibitin (PHB), superoxide dismutase (SOD2) and cytochrome b-c1 complex subunit 1 (UQCRC1) in two groups was detected by western blot analysis. Briefly, per sample, three 20 µm cryostat sections were lysed in 200 µl radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer containing protease inhibitors (Boston Bioproducts, Ashland, MA, USA). Samples were lysed on ice, centrifuged for 10 min at 10,000 × g (4°C) and supernatants were collected. Protein concentrations of the lysates were measured using a QuantiPro™ BCA assay kit. Proteins were loaded onto polyacrylamide gel and separated using 10% SDS-PAGE using the PROTEAN® II xi Cell system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.). Gels were then transferred onto a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (0.2 µm; EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). Following blocking for nonspecific antibody binding with 5% nonfat milk overnight and probing with primary rabbit polyclonal antibody against PHB (cat. no. ab75766; 1:1,000), SOD2 (cat. no. ab1398; 1:1,000) and UQCRC1 (cat. no. ab84901; 1:1,000 (all obtained from Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA) for 1 h at 37°C. Then, the proteins were detected on the blot using horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG H&L (cat. no. ab6702; 1:10,000; Abcam) at 37°C for 30 min visualized at 800 nm fluorescence channels. β-actin was used as an internal control. The blot was developed and quantified by Odyssey Infrared Imaging System version 3.0 (LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE, USA) following the manufacturer's instructions.

Re-identification of typical protein by immunohistochemistry

PHB levels were further examined using immunohistochemistry. The kidney tissues from control and experimental groups of 2, 6 and 8 h following brain death were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 24 h, dehydrated and embedded in paraffin. Paraffin blocks were sectioned into 5 µm-thick slices and fixed with a chilled 1:1 mixture of methanol:acetone for 5 min following pretreatment with 0.3% hydrogen peroxide for 20 min at room temperature. For PHB-specific staining, the sections were incubated by primary polyclonal rabbit antibody (cat. no. ab75766; 1:1,000; Abcam) for 1 h at 37°C. Subsequently, incubation with HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG H&L (1:10,000; Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA) at 37°C for 30 min was followed by reaction with 3,3-diaminobenzidine substrate solution and counterstaining with hematoxylin. A total of five random fields of view of each stained section were pictured and analyzed using morphometric software (MIAS-2000 medical image analysis system; Beijing University of Aeronautics and Astronautics, Beijing, China) by an investigator blind to the study group.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses of the data were performed using SPSS software (version, 18.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). All the data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation. The differences between more than two groups, BUN and Cr values were compared and the relative absorbance of PHB, SOD and UQCRC1 were assessed with a one-way analysis of variance and the post hoc tests used was Student-Newman-Keuls. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

The alteration of renal function

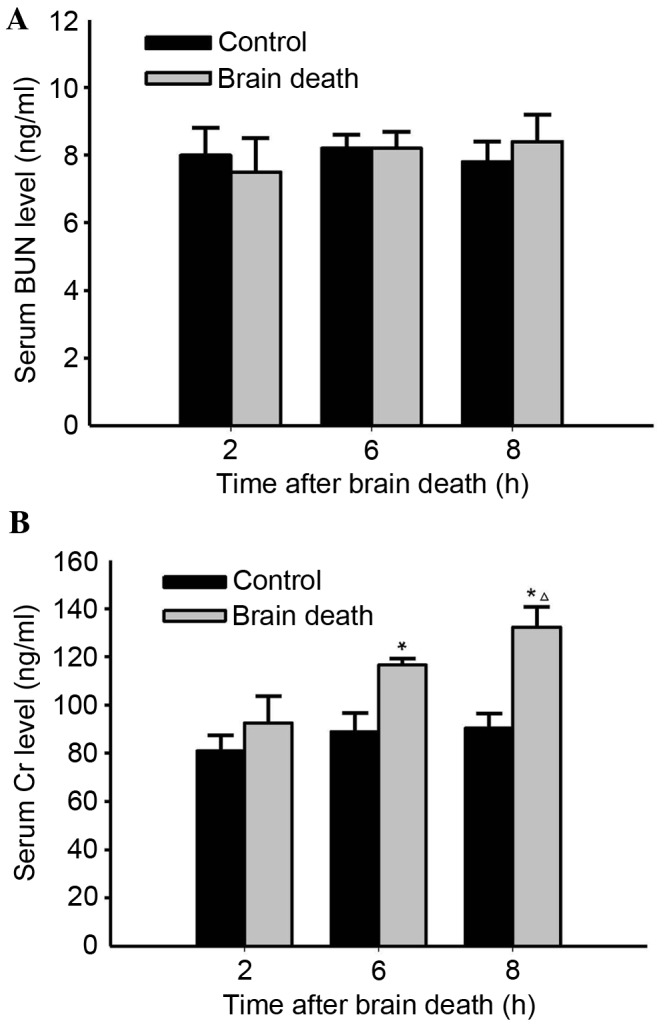

The results indicated that there were no obvious differences in serum BUN levels in the DBD group compared with those in both the previous time point group and the control group during the period following brain death induction to 8 h after this point (P>0.05; Fig. 1A). However, obvious serum Cr level alterations were observed 6 and 8 h following brain death, when compared with those in the control group (P<0.05; Fig. 1B). Particularly, compared with the control group, serum Cr level in the 8 h improved significantly (P<0.05; Fig. 1B).

Figure 1.

Effects of brain death on alteration of serum BUN and Cr levels over 8 h following brain death induction. The serum BUN and Cr levels in control and DBD groups at the time points of 2, 6 and 8 h following brain death were measured using an automatic biochemical analyzer. (A) Neither the control nor DBD groups presented any obvious alterations compared with the other. (B) In DBD groups, the Cr level was significant increased over time (except for at 2 h), when compared with either the control or previous group (n=5; *P<0.05 vs. previous time point (2 h) group; ∆P<0.05 vs. Control). BUN, blood urea nitrogen; Cr, creatinine; DBD, donation after brain death.

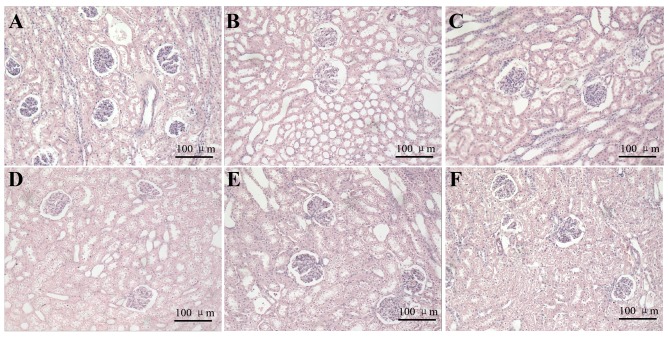

The morphological alteration of kidney

Using the light microscope, kidney cells in the control groups were arranged in neat rows and were stained evenly at different time points. In addition, the structure of glomerular and renal tubule was normal (Fig. 2). The structure of glomerulus in DBD groups at 2 h was relatively normal, as reflected by its similarities to the 2 h control group. In addition, the proximal convoluted tubule at 2 h was similar. However, in the 6 h DBD group, the local vascular dilation and congestion, as well as the degeneration and necrosis in some tubules and the atrophy in some glomeruli, was also observed. In the 8 h DBD group, some tubules had obvious degeneration and even presented cellular edema. Furthermore, vacuolar degeneration in kidney cells and proximal convoluted tubule occlusion were observed (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Effects of brain death on morphological alteration of kidney at over 8 h following brain death induction. Kidney cells in control and DBD groups stained with hematoxylin and eosin (magnification, ×200). (A-C) Time points of 2, 6 and 8 h in the control groups, where kidney cells are arranged in neat rows and were stained evenly. The structure of the glomerulus and renal tubule was normal. (D-F) Time points of 2, 6 and 8 h in the DBD groups, where the structure of glomerulus and proximal convoluted tubule at 2 h were roughly normal compared with control groups l. At 6 h in the DBD group, some tubules presented obvious degeneration and cellular edema. Vacuolar degeneration in kidney cells and proximal convoluted tubule occlusion were observed. At 8 h in the DBD group, the renal tubule cells demonstrated obvious cellular edema and evident inflammation in most areas (n=5). DBD, donation after brain death.

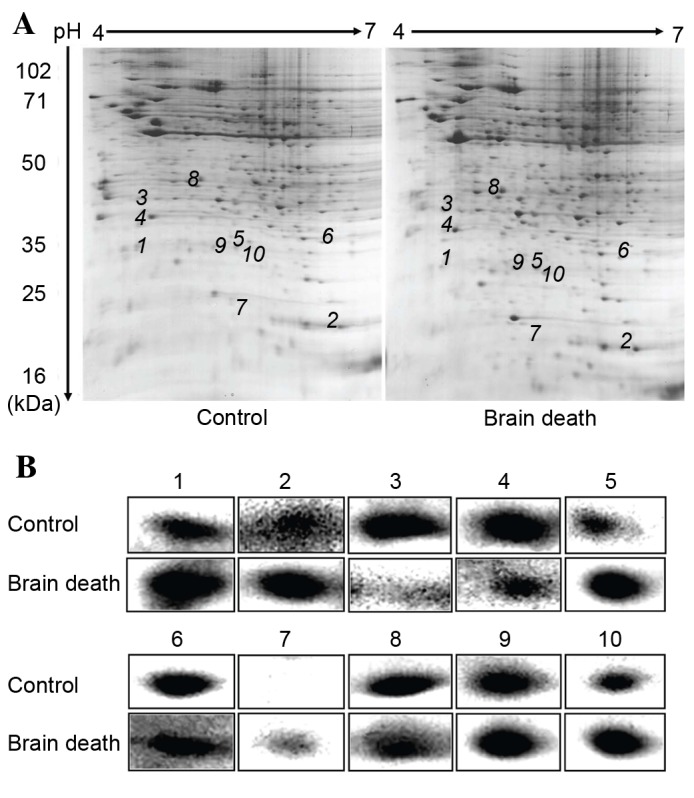

The 2-DE proteomic profiling of different proteins

The total protein maps of the kidney tissue in the 6 h control group and 6 h DBD group were observed and analyzed by 2-DE. Stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue, high resolution 2-DE maps were observed in triplicate. The PDQuest Basic 2-D Analysis software was applied to detect protein spots, subduct background, normalize, match and establish an average gel, respectively. Selecting the weakest, smallest and strongest points, the software synthesized a new gel using the protein point data and matched each other to acquire the map of differentially-expressed proteins. Finally, these differentially-expressed proteins (with a >2-fold difference) were identified. The results demonstrated that 904±19 protein spots in control groups could be detected and 916±25 protein spots in the DBD group could be detected. There were ~45 protein spots that were differentially expressed identified by Voyager-DE STR 4307 MALDI-TOF-MS tandem mass spectrometry analysis. Compared with control groups, 24 proteins were upregulated and 21 proteins were downregulated in DBD experimental groups. The 2-DE map is on presented in Fig. 3A. Partial enlargement of the differentially expressed proteins is presented in Fig. 3B.

Figure 3.

Differential protein expression profile analysis of control and DBD groups using 2-dimensional electrophoresis gels. All samples were separated using isoelectric focusing on first dimension and SDS-PAGE on second dimension. The gels stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue were analyzed using the PD-Quest 2D analysis software. (A) A total of 10 of 42 differentially expressed spots were identified by Voyager-DE STR 4307 MALDI-TOF-MS tandem mass spectrometry analysis (marked with numbers). (B) Partial enlargement of the differentially-expressed proteins in DBD and control groups (1–10; n=5).

Mass spectrum identification and the function classification of different proteins

Excised from the gel, 13 enzymolysis proteins were analyzed by MS to obtain peptide mass fingerprinting and peptide sequence tags, respectively. Using Mascot to query the SWISS-PROT database, the authors identified ten differential expressed proteins. A total of six were upregulated, whereas the other four proteins were downregulated in hepatocellular carcinoma. According to their functions, the proteins were classified as the following groups: Proteins associated with proliferation and differentiation, proteins associated with signal transduction, proteins associated with their modification, proteins associated with the electron transport chain and proteins associated with oxidation reduction. Subcellular localization of these proteins was analyzed using detailed information given by the Swiss-Prot database. These proteins were localized in cytoplasm, mitochondria and nucleus. The detailed information of subcellular localization is listed in Table I.

Table I.

Proteins identified by mass spectrometry.

| Intensity of protein expression (IHC) | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein no. | Protein namea | Gene name | Accession nob | pIc | Sequence coverage (%) | Mascot score | MWC (Da) | Subcellular localization | Biological function | Controld | Brain deathe | P-valuef |

| 1 | Prohibitin, | PHB | P67779 | 5.57 | 65 | 194 | 29859 | Mitochondria | Proliferation | 89274 | 136620 | <0.05 |

| isoform | Cell membrane | Differentiation | ||||||||||

| CRA_b | Cytoplasm | |||||||||||

| 2 | PRP38 pre-mRNA | PRPF38A | D3ZGL5 | 6.63 | 36 | 74 | 10044 | Cytoplasm | Protein | 34122 | 116846 | <0.05 |

| processing factor | modification | |||||||||||

| 38 (yeast) domain | ||||||||||||

| containing A | ||||||||||||

| 3 | Beta-1,3-N- | B3GALNT1 | Q6AY39 | 7.18 | 33 | 75 | 39531 | Cytoplasm | Protein | 88192 | 21820 | <0.05 |

| acetylgalactos | Cell membrane | modification | ||||||||||

| aminyltransferase 1 | ||||||||||||

| 4 | Annexin A5 | ANXA5 | P14668 | 4.93 | 32 | 64 | 35807 | Cytoplasm | Coagulation | 116252 | 72511 | <0.05 |

| function | ||||||||||||

| 5 | Calcineurin | CANB1 | P63100 | 4.64 | 39 | 57 | 19402 | Cytoplasm | Signal | 70458 | 137404 | <0.05 |

| subunit B type 1 | transduction | |||||||||||

| 6 | Superoxide | SOD2 | P09671 | 8.96 | 25 | 56 | 24887 | Cytoplasm | Oxidation | 69771 | 28887 | <0.05 |

| dismutase [Mn], | reduction | |||||||||||

| mitochondrial | ||||||||||||

| 7 | V-type proton | ATP6V1G1 | O75348 | 6.75 | 28 | 69 | 13816 | Cytoplasm | Ion | 7811 | 12435 | <0.05 |

| ATPase | transportation | |||||||||||

| subunit G 1 | ||||||||||||

| 8 | Cytochrome b-c1 complex subunit 1, mitochondrial precursor | UQCRC1 | P86201 | 5.57 | 32 | 112 | 53500 | Mitochondria | Electron transport chain | 90833 | 40277 | <0.05 |

| 9 | NADH [ubiquinone] 1 beta subcomplex subunit 10 | NDUFB10 | Q9DCS9 | 7.57 | 31 | 75 | 21131 | Mitochondria | Electron transport chain | 93262 | 142973 | <0.05 |

| 10 | Peroxiredoxin-3, mitochondrial | PRDX3 | Q9Z0V6 | 7.67 | 61 | 71 | 28017 | Mitochondria microsomes | Oxidation reduction | 70842 | 106290 | <0.05 |

Peptide and fragment ion masses were used to search against the Swiss-Prot databases for protein identifications using the Mascot software. Ion scores (based on mass/mass spectra) were from MALDI-TOF/TOF identification. A Mascot score of >56 was considered as significant (P<0.05).

Accession numbers were derived from the Swiss-Prot database.

Theoretical MW or pI were from the UniProt database.

The Intensity 2-DE Images of protein expression in the control groups.

The Intensity Images of protein expression in the group of 6 h following brain death.

P<0.05 indicates a statistically significant difference compared with the control group. MW, molecular weight; pI, isoelectric point.

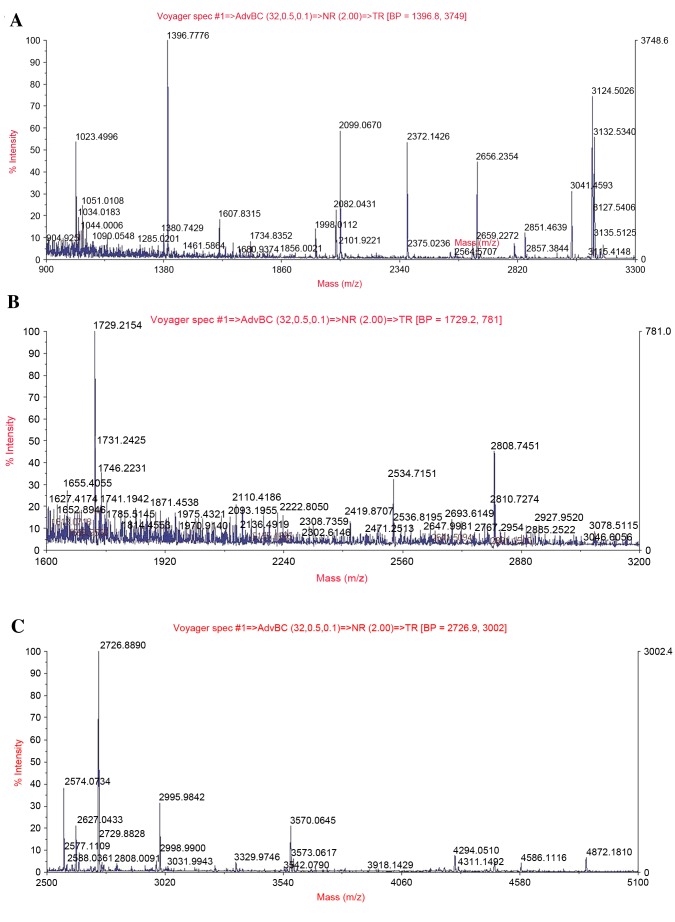

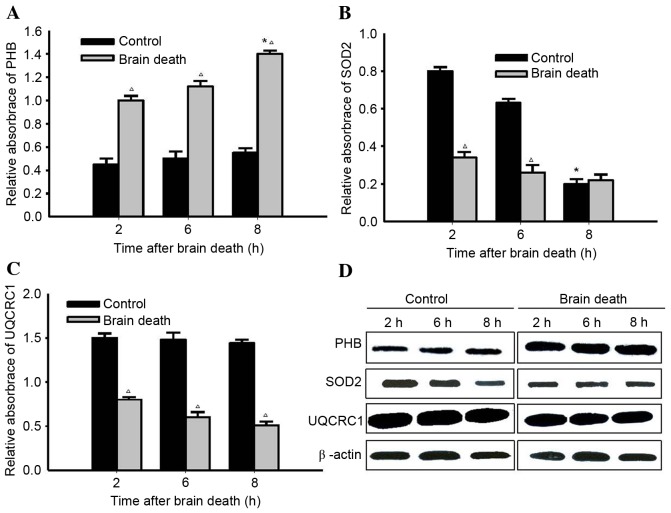

Identification and re-identification of typical proteins

A representative peptide mass fingerprinting map of PHB, SOD2 and UQCRC1 protein spots 1, 6 and 8 is demonstrated in Fig. 4A-C. MS/MS analysis demonstrated that the Mascot score and the sequence coverage of PHB, SOD2 and UQCRC1 were 194 + 65, 56 + 25 and 112 + 32%, respectively. As presented in the western blotting, PHB proteins band in the control groups expressed at a low level. The expression of PHB proteins in kidney tissue from DBD groups increased over time and was highest at 8 h following brain death. In contrast, the expression of SOD2 and UQCRC1 proteins in DBD groups were significantly lower those in the respective control groups (SOD2, P<0.05 at 2 and 6 h; UQCRC1, P<0.05 at 2, 6 and 8 h). (Fig. 5).

Figure 4.

Identification of alterations to PHB, SOD2 and UQCRC1 protein expression using MALDI-TOF tandem mass spectrometry. The acquired spectra were searched in a Mascot Search engine based on the Swiss-Prot protein database. (A) MS/MS spectrum of the precursor ion with m/z 1396.8 for peptide 209 with corresponding peak values was identified as prohibitin. (B) MS/MS spectrum of the precursor ion with m/z 1729.2 for peptide 135 with corresponding peak values was identified as superoxide dismutase. (C) MS/MS spectrum of the precursor ion with m/z 2726.9 for peptide 229 with corresponding peak values was identified as cytochrome b-c1 complex subunit 1.

Figure 5.

Re-identification of 3 typical proteins using western blot analysis. (A) Representative results of PHB in paired DBD and control samples presenting expression levels at various time points. PHB expression in DBD groups increased significantly at 8 h, compared with the control groups at 8 h. At each time point, statistical differences were identified between DBD and control groups. (B) Representative results of SOD2 in paired DBD and control samples demonstrating its expression levels at various time points. The expression in the control group decreased significantly with respect to the DBD group at 8 h. At 2 and 6 h, statistical differences were identified between DBD and control groups. (C) Representative results of UQCRC1 in paired DBD and control samples displaying differential expression at various time points. At each time point, statistical differences were identified between the DBD group and control group. (D) Representative results of western blot analysis of PHB, SOD2 and UQCRC1 in paired DBD groups and control samples with β-actin serving as an internal control. *P<0.05 vs. previous time point groups; ∆P<0.05 vs. Control groups. PHB, prohibitin; DBD, donation after brain death; SOD2, superoxide dismutase; UQCRC1, cytochrome b-c1 complex subunit 1, mitochondrial precursor.

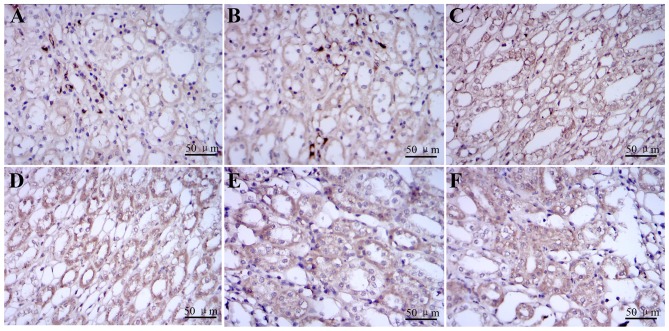

Re-identification of PHB protein using immunohistochemistry

The prohibitin was detected as the yellow brown granular in cytoplasm of renal tubular epithelial cells. The expression of PHB proteins was detected at 2, 6 and 8 h in DBD groups and control groups using immunohistochemistry (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Re-identification of alternation PHB proteins by immunohistochemistry. Representative images (magnification, ×400) of immunohistochemistry analysis of (A-C) paired DBD groups and (D-F) control samples. (A-C) PHB protein was detected as the yellow brown granular in cytoplasm of renal tubular epithelial cells and it was expressed in kidney tissue from control groups. (D-F) The expression of PHB proteins stained in kidney tissue from DBD groups increased over time and peaked at 8 h following brain death. The expressions of PHB in the cytoplasm in each DBD group visibly increased when compared with the control group at the time of 2, 6 and 8 h following brain death. PHB, prohibitin; DBD, donation after brain death.

Discussion

Brain death refers to the irreversible cessation of all functions of the entire brain including the brainstem, as well as a potential future direction in studies involving organ use (20). Many studies have argued that the poor outcomes organs following brain death were mainly associated with hemodynamic alterations (21,22), the release of inflammatory cytokines (23–25), consumption of coagulation factors (26,27) and endocrine and hormonal changes (28–30). However, the molecular mechanism underlying how the status of brain death organs influences the transplantation outcomes remains unclear. Mikhova et al (31) established a porcine model to demonstrate that hemoadsorption of cytokines attenuates brain death-induced ventricular dysfunction. Similar to the method of Pratschke et al (17), in the present study, a novel technique involving progressive intracranial pressure brain death model was used, with the help of a biological functional system, a rodent ventilator and an intelligent temperature control instrument. To ensure that the model induced brain death in a similar fashion to genuine cases, continuous breathing and an electroencephalogram were monitored in real time.

Proteins perform various life functions and have a vital role in cells (32); therefore, identifying differentially expressed proteins in rabbit kidney induced by brain death should provide persuasive evidence that can reveal the molecular mechanism underlying how organs status following brain death influences transplantation outcomes. One of the authors' previous studies using rabbits focused on examining the alterations to liver protein expression (16). A relatively small number of studies have been published on rabbits' kidney injury induced by brain death, including hemodynamic changes, release of inflammatory cytokines, apoptosis, consumption of coagulation factors, endocrine and hormonal changes (1–3). To the best of our knowledge, no prior studies have used proteomics to investigate differentially expressed proteins in rabbit kidney induced by brain death. The results of the current study demonstrated that protein spot 2-DE distribution patterns of DBD groups are greatly different from control groups. A total of 45 spots in the 2-DE gels presented a statistically significant difference in expression. From these spots, a total of 10 altered proteins were identified primarily using MS analysis. One of the downregulated proteins was identified as PHB protein, using the Swiss-Prot database. The peptide pieces (m/z 1396.8) from this protein scored 194 points and the sequences coverage was 65%. Because PHB protein is associated with cell proliferation and differentiation, it raised a high level of concern. PHB protein has been identified as a molecular factor that can mediate anti-apoptotic signals, and is essential for mitochondrial function. It is a member of a highly conserved family of proteins that are thought to serve major roles in cell cycle control, differentiation, senescence and apoptosis (33). Liu et al (34) has previously indicated that downregulation of PHB can trigger oxidative stress and result in organ or tissue damage. Using immunohistochemistry techniques in the present study, PHB protein was screened and identified, as it may be associated with injury induced by brain death. To ensure the reliability of preliminary screening and the feasibility of follow-up study, the expression of PHB proteins in kidney tissues was validated. As demonstrated, the expression of PHB proteins in kidney tissue from DBD groups increased over time, which indicated that PHB protein may be a key factor affecting the kidney injury.

Acknowledgements

The present study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. U1403222) and the Natural Science Fund of Hubei Province (grant no. 2015CFA018).

References

- 1.Li Y, Li J, Fu Q, Chen L, Fei J, Deng S, Qiu J, Chen G, Huang G, Wang C. Kidney transplantation from brain-dead donors: Initial experience in China. Transplant Proc. 2016;48:2592–2595. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2016.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sui WG, Yan Q, Xie SP, Chen HZ, Li D, Hu CX, Peng WJ, Dai Y. Successful organ donation from brain dead donors in a Chinese organ transplantation center. Am J Transplant. 2011;11:2247–2249. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03694.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang C, Liu L, Fu Q, Meng F, Li J, Deng S, Fei J, Yuan X, Han M, Chen L, et al. Kidney transplantation from donors after brain or cardiac death in China-a clinical analysis of 94 cases. Transplant Proc. 2013;45:1323–1326. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2013.01.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang L, Zeng L, Gao X, Wang H, Zhu Y. Transformation of organ donation in China. Transpl Int. 2015;28:410–415. doi: 10.1111/tri.12467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sun Q, Gao X, Ko DS, Li XC. Organ transplantation in China-not yet a new era-Authors' reply. Lancet. 2014;384:741–742. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61429-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kosmoliaptsis V, Salji M, Bardsley V, Chen Y, Thiru S, Griffiths MH, Copley HC, Saeb-Parsy K, Bradley JA, Torpey N, Pettigrew GJ. Baseline donor chronic renal injury confers the same transplant survival disadvantage for DCD and DBD kidneys. Am J Transplant. 2015;15:754–763. doi: 10.1111/ajt.13009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hatamizadeh P, Molnar MZ, Streja E, Lertdumrongluk P, Krishnan M, Kovesdy CP, Kalantar-Zadeh K. Recipient-related predictors of kidney transplantation outcomes in the elderly. Clin Transplant. 2013;27:436–443. doi: 10.1111/ctr.12106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mertes PM, el Abassi K, Jaboin Y, Burtin P, Pinelli G, Carteaux JP, Burlet C, Boulange M, Villemot JP. Changes in hemodynamic and metabolic parameters following induced brain death in the pig. Transplantation. 1994;58:414–418. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199408270-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barklin A, Larsson A, Vestergaard C, Kjaergaard A, Wogensen L, Schmitz O, Tønnesen E. Insulin alters cytokine content in two pivotal organs after brain death: A porcine model. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2008;52:628–634. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2008.01606.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lisman T, Leuvenink HG, Porte RJ, Ploeg RJ. Activation of hemostasis in brain dead organ donors: An observational study. J Thromb Haemost. 2011;9:1959–1965. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2011.04442.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fang H, Zhang S, Guo W, Cao S, Yan B, Lu Y, Li J. Cobalt protoporphyrin protects the liver against apoptosis in rats of brain death. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2015;39:475–481. doi: 10.1016/j.clinre.2014.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oberhuber R, Ritschl P, Fabritius C, Nguyen AV, Hermann M, Obrist P, Werner ER, Maglione M, Flörchinger B, Ebner S, et al. Treatment With tetrahydrobiopterin overcomes brain death-associated injury in a murine model of pancreas transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2015;15:2865–2876. doi: 10.1111/ajt.13364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Qureshi MS, Callaghan CJ, Bradley JA, Watson CJ, Pettigrew GJ. Outcomes of simultaneous pancreas-kidney transplantation from brain-dead and controlled circulatory death donors. Br J Surg. 2012;99:831–838. doi: 10.1002/bjs.8733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pratschke J, Wilhelm MJ, Kusaka M, Basker M, Cooper DK, Hancock WW, Tilney NL. Brain death and its influence on donor organ quality and outcome after transplantation. Transplantation. 1999;67:343–348. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199902150-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tezel G. A proteomics view of the molecular mechanisms and biomarkers of glaucomatous neurodegeneration. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2013;35:18–43. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2013.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Du B, Li L, Zhong Z, Fan X, Qiao B, He C, Fu Z, Wang Y, Ye Q. Brain death induces the alteration of liver protein expression profiles in rabbits. Int J Mol Med. 2014;34:578–584. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2014.1806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pratschke J, Wilhelm MJ, Kusaka M, Laskowski I, Tilney NL. A model of gradual onset brain death for transplant-associated studies in rats. Transplantation. 2000;69:427–430. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200002150-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shevchenko A, Wilm M, Vorm O, Mann M. Mass spectrometric sequencing of proteins silver-stained polyacrylamide gels. Anal Chem. 1996;68:850–858. doi: 10.1021/ac950914h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jou YC, Fang CY, Chen SY, Chen FH, Cheng MC, Shen CH, Liao LW, Tsai YS. Proteomic study of renal uric acid stone. Urology. 2012;80:260–266. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2012.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sade RM. Brain death, cardiac death, and the dead donor rule. J S C Med Assoc. 2011;107:146–149. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Avlonitis VS, Wigfield CH, Kirby JA, Dark JH. The hemodynamic mechanisms of lung injury and systemic inflammatory response following brain death in the transplant donor. Am J Transplant. 2005;5:684–693. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2005.00755.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rostron AJ, Avlonitis VS, Cork DM, Grenade DS, Kirby JA, Dark JH. Hemodynamic resuscitation with arginine vasopressin reduces lung injury after brain death in the transplant donor. Transplantation. 2008;85:597–606. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e31816398dd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kuecuek O, Mantouvalou L, Klemz R, Kotsch K, Volk HD, Jonas S, Wesslau C, Tullius S, Neuhaus P, Pratschke J. Significant reduction of proinflammatory cytokines by treatment of the brain-dead donor. Transplant Proc. 2005;37:387–388. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2004.12.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koudstaal LG, t Hart NA, Ottens PJ, van den Berg A, Ploeg RJ, van Goor H, Leuvenink HG. Brain death induces inflammation in the donor intestine. Transplantation. 2008;86:148–154. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e31817ba53a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Auraen H, Mollnes TE, Bjørtuft Ø, Bakkan PA, Geiran O, Kongerud J, Fiane A, Holm AM. Multiorgan procurement increases systemic inflammation in brain dead donors. Clin Transplant. 2013;27:613–618. doi: 10.1111/ctr.12175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hvas CL, Fenger-Eriksen C, Høyer S, Sørensen B, Tønnesen E. Hypercoagulation following brain death cannot be reversed by the neutralization of systemic tissue factor. Thromb Res. 2013;132:300–306. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2013.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wu X, Du Z, Yu J, Sun Y, Pei B, Lu X, Tang Z, Yin M, Zhou L, Hu J. Activity of factor VII in patients with isolated blunt traumatic brain injury: Association with coagulopathy and progressive hemorrhagic injury. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2014;76:114–120. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3182a8fe48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leber B, Stadlbauer V, Stiegler P, Stanzer S, Mayrhauser U, Koestenbauer S, Leopold B, Sereinigg M, Puntschart A, Stojakovic T, et al. Effect of oxidative stress and endotoxin on human serum albumin in brain-dead organ donors. Transl Res. 2012;159:487–496. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2011.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vespa PM. Hormonal dysfunction in neurocritical patients. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2013;19:107–112. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0b013e32835e7420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ranasinghe AM, Bonser RS. Endocrine changes in brain death and transplantation. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;25:799–812. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mikhova KM, Don CW, Laflamme M, Kellum JA, Mulligan MS, Verrier ED, Rabkin DG. Effect of cytokine hemoadsorption on brain death-induced ventricular dysfunction in a porcine model. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2013;145:215–224. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2012.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vazquez A, Flammini A, Maritan A, Vespignani A. Global protein function prediction from protein-protein interaction networks. Nat Biotechnol. 2003;21:697–700. doi: 10.1038/nbt825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chowdhury I, Branch A, Olatinwo M, Thomas K, Matthews R, Thompson WE. Prohibitin (PHB) acts as a potent survival factor against ceramide induced apoptosis in rat granulosa cells. Life Sci. 2011;89:295–303. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2011.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu T, Tang H, Lang Y, Liu M, Li X. MicroRNA-27a functions as an oncogene in gastric adenocarcinoma by targeting prohibitin. Cancer Lett. 2009;273:233–242. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]