Abstract

Reduced hepatic glycogenesis is one of the most important causes of metabolic abnormalities in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Octreotide, a somatostatin analogue, has been demonstrated to promote weight loss and improve metabolic disorders in mice with high fat diet (HFD)-induced obesity. However, whether octreotide affects hepatic glycogenesis is unknown. The aim of the present study was to verify the effects of octreotide on hepatic glycogenesis in rats with HFD-induced obesity. Male Sprague-Dawley rats were fed a standard diet or a HFD for 24 weeks. Obese rats from the HFD group were further divided into a HFD-control group and an octreotide-administered group. Rats in the latter group were injected with octreotide for 8 days. Glucose and insulin tolerance tests were performed, and the area under the curve (AUC) was calculated. Following sacrifice, their body weights and lengths, fasting plasma glucose (FPG), fasting insulin (FINS), serum triglyceride (TG), total cholesterol (TC), free fatty acid (FFA), alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) levels were measured. In addition, Lee's index and the homeostatic model assessment index were calculated. Hepatic TG, FFA levels and glycogen content were first determined. Hepatic steatosis in the obese rats was assessed based on hematoxylin and eosin and Oil Red O staining. Human hepatoblastoma HepG2 cells were divided into a control group, a palmitate (PA)-treated group and a PA + octreotide-treated group. Establishment of the in vitro fatty liver model using HepG2 cells was confirmed by Oil Red O staining. The expression of phosphorylated Akt and glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK3β) was detected by western blotting, and glycogen synthase (GS) mRNA levels were detected by reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction. Compared with the control group, the body weight, Lee's index, AUC of the intraperitoneal glucose tolerance test and intraperitoneal insulin tolerance test, levels of FPG, FINS, TG, TC, FFA, ALT and AST, and HOMA index values were significantly increased in the obese rats. The body weight, levels of FPG and FINS, and the HOMA index were significantly reduced following octreotide treatment, whereas the decrease in Lee's index, the blood levels of ALT, AST, TC, TG and FFA, and the AUC did not reach statistical significance. Hepatic TG and FFA levels were significantly increased and hepatic glycogen content was significantly decreased in rats with HFD-induced obesity when compared with those in the control group. Octreotide intervention restored these alterations. The expression levels of phosphorylated Akt and GSK3β protein expression, as well as GS mRNA levels in the HFD group were lower when compared with those in the control group, whereas octreotide treatment reversed these reductions. The in vitro experiments demonstrated that the reduced levels of phosphorylated Akt and GSK3β protein, and GS mRNA in the PA-treated group were significantly reversed by octreotide treatment. In conclusion, the results indicate that octreotide improved hepatic glycogenesis and decreased FPG concentration in rats with HFD-induced obesity. These mechanisms may be associated with increased GS activity via the promotion of GSK3β phosphorylation. Therefore, octreotide may be regarded as a novel therapeutic strategy for HFD-induced obesity and obesity-associated metabolic disorders.

Keywords: octreotide, obesity, glycogen synthesis, phosphorylated glycogen synthase kinase 3β, phosphorylated protein kinase B, glycogen synthase

Introduction

In the last decade, obesity has become increasingly prevalent in industrialized countries and has gradually become common in developing countries (1). As the incidence of obesity has increased, the risks for obesity-associated diseases, such as non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), have increased. NAFLD is considered to be the most common cause of chronic liver disease and is associated with obesity. The development of NAFLD is associated with type 2 diabetes, with >90% of obese patients with type 2 diabetes additionally diagnosed with NAFLD (2). Insulin resistance is thought to be the most common underlying cause of type 2 diabetes and NAFLD pathogenesis (3). Insulin resistance is characterized by the impaired ability of insulin to inhibit endogenous glucose production. In addition, insulin-mediated inhibition of lipolysis is reduced, leading to increased lipolysis of peripheral adipose tissues and increased levels of free fatty acids (FFA) in the peripheral blood, which contributes to the elevated transport of FFA to the liver. Insulin resistance-induced hyperinsulinemia and hyperglycemia facilitate the abundant accumulation of lipids in hepatocytes by increasing de novo lipogenesis and inhibiting fatty acid oxidation and hepatic lipid output, which leads to hepatic steatosis (4).

Insulin resistance is defined as reduced insulin sensitivity in target organs, which include the liver and muscle (5). The liver is the primary organ for the maintenance of blood glucose homeostasis. Insulin decreases blood glucose levels by reducing hepatic gluconeogenesis and increasing hepatic glycogenesis and glucose uptake; this progress is dependent on the Akt/glycogen synthase kinase (GSK) signaling pathway (6,7). Insulin binds to the insulin receptor and stimulates insulin receptor-linked tyrosine kinase phosphorylation, which further phosphorylates insulin receptor substrate 1 (IRS1). Activated IRS1 initiates the phosphorylation of a number of downstream signaling molecules, leading to further activation of Akt. Activated Akt inactivates GSK3β by phosphorylating Ser9, which results in activation of glycogen synthase (GS). This subsequently promotes increased hepatic glycogenesis (7). GSK3β, a serine/threonine protein kinase located in the cytoplasm, is a negative regulator of the insulin-signaling pathway that decreases hepatic glycogenesis via the phosphorylation and inactivation of GS (8). A previous study reported that hepatic GSK3β activity is elevated in animal models of type 2 diabetes or insulin resistance, which in turn, decreases hepatic glycogenesis by suppressing GS activity (9). Treatment with a GSK3β inhibitor improved hepatic glycogenesis by increasing insulin sensitivity (9). Therefore, inhibition of GSK3β activity may be one of the more efficient methods for improving insulin resistance.

Somatostatin (SST) is a neurohormone with extensive biological activities, including decreasing insulin and glucagon secretion, inhibiting gastric emptying and gastric acid secretion, and reducing intestinal absorption of nutrients (10). Octreotide, an SST analogue, has a longer half-life and demonstrates more robust effects. A previous study indicated that octreotide decreases body weight, reduces insulin hypersecretion and improves metabolic abnormalities in mice with high fat diet (HFD)-induced obesity (11). However, whether octreotide exerts a positive effect on hepatic glycogen synthesis in rats with HFD-induced obesity remains unknown. The present study investigated the effects and the underlying mechanism of octreotide on hepatic glycogenesis in rats with HFD-induced obesity.

Materials and methods

Animals and treatment

The animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Sichuan University (Chengdu, China). A total of 40 healthy male Sprague-Dawley (SD) rats (age, 3 weeks; weight, 40–60 g) were purchased from the Experimental Animal Centre of Sichuan University and raised in the Experimental Animal Centre of West China Hospital, Sichuan University. All rats were caged (n=4 per cage) under standard conditions with controlled humidity (45 to 65%) and temperature (20 to 25°C), 12/12 h light/dark cycles and access to food and water ad libitum. Rats were maintained for 7 days on a standard diet before they were divided into the normal diet group (320 kcal/100 g body weight, 4.65% calories derived from fat; n=12) and the HFD group (500 kcal/100 g body weight, 60% calories derived from fat; n=28). The feed for these diets were purchased from Trophic Animal Feed High-Tech Co., Ltd. (Jiangsu, China). Body weight, body length and tail length were measured every week for 24 weeks, and Lee's index was calculated using the following formula: [Body weight (g)1/3 × 1,000]/body length (cm) (12). Following 24 weeks, rats with a mean body weight that reached ≥1.4-fold higher than that of controls were selected for further experiments. A total of 24 eligible rats were separated from the HFD group at random and divided into the HFD-control group (n=12) and the octreotide-treated group (n=12). These groups were continuously fed a HFD for 8 days, and rats in the octreotide-treated group were subcutaneously injected with octreotide (Chengdu Tiantai Mountain Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Chengdu, China) at a dose of 40 µg/kg body weight every 12 h for 8 days. During the octreotide administration period, body weight and food intake were monitored daily. At the end of the experiment, all rats underwent a 12-h starvation period and were sacrificed with 2% sodium pentobarbital (45 mg/kg body weight; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) administered intraperitoneally. Following sacrifice, blood samples were collected and centrifuged at 860 × g for 15 min at 4°C, and the supernatant was stored at −80°C for further analysis. The liver tissues were isolated, and one sample was rapidly frozen in liquid nitrogen prior to storage at −80°C for total RNA and protein extraction or Oil Red O staining. A second sample was fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 48 h at room temperature for histological examination. Abdominal fat was also collected and weighed.

Intraperitoneal glucose tolerance test (ipGTT) and insulin tolerance test (ipITT)

Following fasting for 12 h, rats were subjected to the ipGTT and ipITT assays by intraperitoneal administration of glucose at 2.0 g/kg body weight or insulin at 7.5 U/kg body weight, respectively. Blood samples were drawn from the tail vein at 0, 15, 30, 60 and 120 min post-injection, and the glucose levels were measured using an Accu-Chek Active Glucometer (ACCU-CHEK Active; Roche Applied Science, Penzberg, Germany).

GraphPad Prism software (version 5.0; GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA) was used to calculate the area under the curve (AUC) of ipGTT and ipITT, and the results are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation.

Plasma metabolic parameters

Fasting plasma glucose (FPG), serum triglyceride (TG), total cholesterol (TC), alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) levels were determined using the following reagent kits according to the manufacturer's protocol: GLU assay kit (cat. no. A031), TG assay kit (cat. no. A027), T-CHO assay kit (cat. no. A030), GPT assay kit (cat. no. A001) and a GOT assay kit (cat. no. A002), obtained from Changchun Huili Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Changchun, China. FFA levels were determined using a Non-Esterified Free Fatty Acids assay kit (cat. no. FA115; Randox Laboratories, Ltd., Crumlin, UK) and serum insulin levels were detected using a rat insulin enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kit (cat. no. EZRMI-13K; EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA), according to the manufacturer's instructions. The homeostatic model assessment (HOMA) index, which is an assessment of insulin sensitivity, was calculated to assess the insulin sensitivity of obese rats using the following equation: [FPG (mmol/l) × fasting serum insulin (µU/ml)]/22.5.

Measurement of liver TG and FFA content

To assess hepatic TG levels, ~50 mg liver tissue from rats in all experimental groups was homogenized in a 2:1 chloroform-methanol mixture (v/v). The homogenized solution was mixed on a shaker for 20 min at room temperature, centrifuged at 310 × g for 10 min at 4°C, and the supernatant was collected. A total of 0.2x the supernatant volume of NaCl solution (0.9%) was added to the supernatant. The mixture was then centrifuged at 550 × g for 20 min at 4°C, and the resulting supernatant was collected and dried under a stream of nitrogen gas. To the residue, 0.5 ml Triton X-100 solution (3%) was added to re-dissolve the residue. The TG level of the 0.5 ml Triton X-100 solution was measured using a TG assay kit (cat. no. A027; Changchun Huili Biotechnology Co., Ltd.).

In order to determine hepatic FFA levels, ~50 mg liver tissue was homogenized in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), centrifuged at 860 × g for 20 min at 4°C and the supernatant was collected. The protein concentrations of the supernatant were measured using a bicinchoninic (BCA) Protein assay kit (Pierce; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA), and the hepatic FFA concentration was detected using a Nonesterified Free Fatty Acid assay kit (cat. no. FA115; Randox Laboratories, Ltd.) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The FFA values are presented as mM/g protein.

Measurement of liver glycogen content

In order to assess hepatic glycogen content, ~50 mg liver tissue was homogenized in 500 µl ice-cold PBS. The homogenates were centrifuged at 14,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C, and the supernatants were collected for analysis using glycogen content assays. The glycogen concentration in the liver was evaluated using an EnzyChrom™ Glycogen assay kit (BioAssay Systems, Hayward, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Glycogen concentration was normalized to the protein concentration of liver tissues.

Analysis of liver histology and Oil Red O staining

Formalin-fixed liver tissues were embedded with paraffin and sectioned (3-µm). Sections subsequently underwent xylene gradient dewaxing twice for 10 min and gradient dehydration with 100% alcohol for 3 min, 100% alcohol for 3 min, 95% alcohol for 3 min and 90% alcohol for 3 min. Sections were rinsed with tap water three times and immersed in tap water for 15 min. Sections were then stained with 0.2% hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) for ~5 min at room temperature. White fat vacuoles and steatosis were visualized using a light microscope (Olympus BX41TF Microscope; Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan), and images were captured at ×400 magnification. Evaluation of NAFLD was performed described previously (13).

Frozen liver tissue was embedded with Tissue-Tek O.C.T. Compound (Sakura Finetek USA, Inc., Torrance, CA, USA), and cryosections (5-µm in thickness) of liver tissue were prepared. The sections were then stained for 30 min in 0.3% freshly diluted Oil Red O solution at 37°C, followed by counterstaining with 0.2% H&E at 37°C for 30 sec following washing with tap water. Images of the sections were collected using a light microscope (Olympus Corporation) from five different fields at ×400 magnification. Image Pro Plus software (version 6.0; Media Cybernetics, Inc., Rockville, MD, USA) was used to analyze the integrated optical density (IOD) of the Oil Red O-stained areas. Quantitative analysis of liver tissue photomicrographs was performed as described previously (14).

HepG2 cell culture and treatment

The human hepatoblastoma HepG2 cell line, which was originally thought to be derived from a hepatocellular carcinoma, however was later determined to be derived from a human hepatoblastoma (15), was obtained from CoBioer Biosciences Co., Ltd. (Nanjing, China). HepG2 cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium (Hyclone; GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Logan, UT, USA) with 10% fetal bovine serum (Biological Industries Israel, Beit Haemek Ltd., Beit Haemek, Israel), 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 µg/ml streptomycin (Hyclone; GE Healthcare Life Sciences). The cells were maintained at 37°C under humidified conditions with 95% O2 and 5% CO2. When cell confluence had reached 80%, cells were starved of glucose overnight in serum-free or 0.5% low-concentration fetal bovine serum (Biological Industries Israel, Beit Haemek Ltd., Beit Haemek, Israel) RPMI-1640 medium and then divided into the following 3 groups: The standard control group, where cells were incubated with 0.5% bovine serum albumin (BSA; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) for 24 h; the palmitate (PA)-treated group, where cells were cultured with 125 µM PA (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) plus 0.5% BSA for 24 h; and the PA plus octreotide-treated group, where cells were cultured with 125 µM PA plus 0.5% BSA for 24 h prior to treatment with 10−8 mmol/l octreotide for 6 h. Subsequently, cells in all groups were incubated with 100 µM insulin for 20 min prior to cell collection. A KeyGEN Whole Cell assay kit (Nanjing KeyGen Biotech Co., Ltd., Nanjing, China) was used to isolate total protein. TRIzol reagent (Takara Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Dalian, China) was used to extract the total mRNA, according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Oil Red O staining of HepG2 cells

Cells (1×106) were washed in PBS three times and then fixed for 30 min with 4% formaldehyde solution at room temperature. Following two washes with 60% isopropyl alcohol, the cells were stained with a working solution of 0.3% Oil Red O for 30 min at 37°C. The reagent was then removed, cells were washed several times with tap water and cell nuclei were counterstained with 0.2% hematoxylin for ~20 sec at room temperature. Photomicrographs of stained cells were captured using a light microscope (Olympus Corporation) at ×400 magnification and the results were analyzed using the aforementioned methods.

RNA isolation and reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR)

TRIzol reagent was used to extract total RNA from liver tissues or HepG2 cells, according to the manufacturer's instructions. RNA (2 µg) was reverse transcribed to cDNA using the RevertAid First Strand cDNA Synthesis kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) according to the manufacturer's instructions. qPCR was performed using 2X SYBR-Green Master Mix (Biotool, LLC, Houston, TX, USA) and the primers listed in Table I (TSINGKE Biological Technology, Co., Ltd., Beijing, China). Samples were analyzed in triplicate and the thermal cycling parameters were as follows: 95°C for 5 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 sec and 60°C for 30 sec. The CFX96 Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA) was used for qPCR analysis. Target gene mRNA expression levels were normalized to β-actin mRNA in the same sample. The relative method of quantification was applied to calculate ΔΔCq values in each sample, and the results are expressed as 2−ΔΔCq (16).

Table I.

Primer sequences used for reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction analysis.

| Gene (organism) | NCBI reference sequence | Forward sequence (5′-3′) | Reverse sequence (5′-3′) | Product size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β-actin (rat) | NM_031144 | CGAGTACAACCTTCTTGCAGC | CCTTCTGACCCATACCCACC | 209 |

| GS (rat) | NM_013089 | AAGAGTTTGTCCGAGGCTGTC | ACCAGAGAGGTTCGTAGTCACAC | 119 |

| β-actin (human) | NM_001101 | CACAGAGCCTCGCCTTT | GGTGCCAGATTTTCTCCAT | 318 |

| GS (human) | NM_002103 | GCCTTTCCAGAGCACTTCAC | CTCCTCGTCCTCATCGTAGC | 195 |

Primers were synthesized by TSINGKE Biological Technology, Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China). NCBI, National Centre for Biotechnology Information; GS, glycogen synthase.

Western blotting

Total protein was isolated from liver tissues or HepG2 cells using a KeyGEN Whole Cell assay kit (Nanjing KeyGen Biotech Co., Ltd.), and the Enhanced BCA Protein assay kit (Pierce; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) was used to measure protein concentrations, according to the manufacturer's instructions. Protein samples (40 µg) from each group were electrophoresed on 10% SDS-PAGE gels and then blotted onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (EMD Millipore). The membranes were blocked with 5% non-fat milk in Tris-buffered saline-Tween-20 (TBST; 0.1%) at room temperature for 2 h, prior to incubation with anti-phosphorylated (p)-Akt rabbit monoclonal antibody (mAb; cat. no. 4060; dilution, 1:1,000; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc., Danvers, MA, USA), anti-p-GSK3β rabbit mAb (cat. no. 9323; dilution, 1:1,000; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.), anti-Akt rabbit polyclonal antibody (cat. no. STJ91543; dilution, 1:500; St. John's Laboratory Ltd., London, UK), anti-GSK3β rabbit polyclonal antibody (cat. no. STJ93448; dilution, 1:500; St John's Laboratory Ltd.), anti-β-actin mouse mAb (cat. no. EM21002; dilution, 1:5,000; Epitomics, Burlingame, CA, USA) at 4°C overnight. This was followed by incubation with a homologous horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (cat. no. ZB2301; dilution, 1:10,000; Beijing Zhongshan Golden Bridge Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) for 2 h at room temperature following washing with TBST. Protein bands were immunodetected using enhanced chemiluminescence reagent (Beijing Zhongshan Golden Bridge Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China), according to the manufacturer's instructions. The intensity of the bands was analyzed using Quantity One software (version 4.6.2; Bio-Rad Laboratories). The expression levels of all proteins in each sample were normalized to β-actin levels, and the experiment was repeated three times.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS software (version 20.0; IBM SPSS, Armonk, NY, USA) and the results are presented as the mean ± standard deviation. One-way analysis of variance followed by the Dunnett's test was performed to evaluate the significant differences among groups. The homogeneity of variances (Levene's test) was necessary, if there is heterogeneity of variance, that is P<0.05, then the method of the variable conversion such as Lg10 is required to meet the homogeneity of variance (P>0.05). P<0.05 was considered to indicate statistically significant differences.

Results

Body weight, Lee's index, liver weight, abdominal fat and abdominal fat index

At the end of the experiment, the body weight of rats in the HFD group had increased by 28.5% when compared with the control group (P<0.01; Table II). Lee's index, which provides an estimate of obesity in adult rats, was also increased by 5.0% in the HFD group when compared with the control group (P<0.01; Table II). The liver weight and quantity of abdominal fat in obese rats was higher than that of the control rats (both P<0.01; Table II), and the abdominal fat index in the obese rats was higher in the HFD group when compared with the control group (P<0.01; Table II). Apart from Lee's index values, octreotide treatment significantly reduced these parameters in rats fed on a HFD (Table II).

Table II.

Body weight, Lee's index, liver weight, abdominal fat and abdominal fat index of rats in the three experimental groups.

| Parameter | Control group (n=12) | HFD group (n=12) | Octreotide-treated group (n=12) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Body weight (g) | 472.08±30.61 | 606.58±57.11aa | 534.42±49.15bb |

| Lee's index | 306.82±4.96 | 322.30±8.82aa | 315.32±12.28a |

| Liver weight (g) | 12.16±1.64 | 14.88±1.41aa | 12.46±1.05bb |

| Abdominal fat (g) | 10.36±4.72 | 28.87±8.76aa | 20.02±4.83bb |

| Abdominal fat index (%) | 2.16±0.88 | 4.72±1.23aa | 3.75±0.81b |

Abdominal fat index was calculated using the following formula: Abdominal fat index (%)=(abdominal fat/body weight) ×100.

P<0.05

P<0.01 and vs. the control group

P<0.05

P<0.01 vs. the HFD group. HFD, high-fat diet.

Serum lipids, ALT, AST, insulin levels, plasma glucose levels and HOMA index values

When compared with the control group, plasma glucose levels in rats from the HFD group were significantly elevated (P<0.01; Table III). Following administration of octreotide, the plasma glucose levels were significantly lower compared with those observed in the obese rats of the HFD group (P<0.01; Table III). Rats in the HFD group exhibited the highest serum insulin, TG, TC, FFA, ALT and AST levels among the three groups (Table III). Octreotide intervention significantly decreased the serum insulin concentration (P<0.05); however, there was no marked reduction in serum TG, TC, FFA, ALT and AST levels (P>0.05). The HOMA index, which provides an estimation of insulin resistance, significantly increased in rats from the HFD group when compared with the control rats (P<0.01), and was significantly inhibited by octreotide treatment (P<0.01; Table III).

Table III.

Blood biochemistry parameters and HOMA indexes in the three experimental groups.

| Parameter | Control group (n=12) | HFD group (n=12) | Octreotide-treated group (n=12) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plasma glucose (mmol/l) | 4.60±1.17 | 6.26±1.55aa | 4.75±1.60bb |

| Serum insulin (mmol/l) | 118.33±37.08 | 157.68±43.55a | 108.85±66.36b |

| Serum FFA (mmol/l) | 225.36±88.20 | 372.12±125.94aa | 311.11±71.82 |

| Serum TG (mmol/l) | 0.39±0.17 | 0.61±0.23a | 0.50±0.14 |

| Serum TC (mmol/l) | 1.68±0.44 | 2.54±0.62aa | 2.31±0.44 |

| Serum ALT (mmol/l) | 54.35±10.32 | 64.21±9.13aa | 62.80±7.66 |

| Serum AST (mmol/l) | 123.58±11.38 | 143.95±17.68aa | 137.64±16.31 |

| HOMA-index | 23.47±8.86 | 39.57±13.48aa | 23.40±16.71bb |

P<0.05

P<0.01 and vs. the control group

P<0.05

P<0.01 vs. the HFD group. HFD, high-fat diet; FFA, free fatty acid; TG, serum triglyceride; TC, total cholesterol; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; HOMA, homeostatic model assessment.

ipGTT and ipITT results

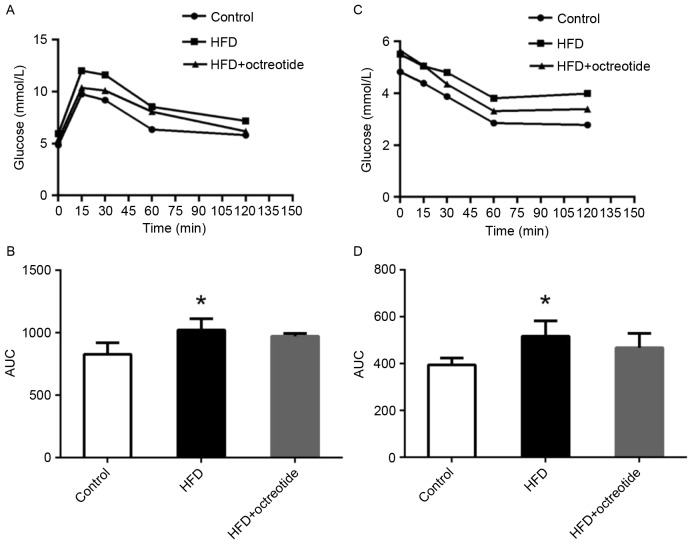

As shown in Fig. 1A, the blood glucose concentration of rats in the HFD group at 0, 15, 30, 60 and 120 min was higher than that observed in the control rats, and the relative AUC increased by 27.7% (P<0.05; Fig. 1B). Similarly, glucose levels in rats from the HFD group was higher when compared with the control group following the ipITT test (Fig. 1C), and the AUC of ipITT in the HFD group increased by 28.8% when compared with the control group (P<0.05; Fig. 1D). Compared with the HFD group, the ipGTT and ipITT AUCs decreased by 5.2 and 10.5% in the octreotide-treated group, respectively, which did not reach statistical significance (Fig. 1B and D).

Figure 1.

Effect of octreotide on insulin resistance in rats with HFD-induced obesity. (A) The glycemic curve during the ipGTT and (B) the AUC of ipGTT. (C) The glycemic curve during the ipITT and (D) the AUC of ipGTT. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation of three independent experiments. *P<0.05 vs. control group. HFD, high fat diet; ipGTT, intraperitoneal glucose tolerance test; ipITT, intraperitoneal insulin tolerance test; AUC, area under the curve.

Hepatic TG, FFA levels and glycogen content

In the HFD-fed rats, hepatic TG and FFA levels were significantly increased and the hepatic glycogen content was significantly decreased when compared with the control group (P<0.01; Table IV). Following octreotide treatment, the hepatic TG and FFA levels were significantly decreased when compared with the HFD group (P<0.01; Table IV). By contrast, hepatic glycogen content significantly increased in the octreotide-treated group when compared with the HFD group (P<0.05; Table IV).

Table IV.

Levels of hepatic serum TG, FFA and glycogen content in each group.

| Parameter | Control group (n=12) | HFD group (n=12) | Octreotide-treated group (n=12) |

|---|---|---|---|

| TG (mg/g liver) | 9.28±3.02 | 29.94±14.63aa | 18.11±7.08bb |

| FFA (mmol/g protein) | 36.10±7.62 | 61.22±16.04aa | 40.86±5.09bb |

| Glycogen (mg/g protein) | 7.17±1.33 | 3.66±0.84aa | 4.77±0.78b |

HFD, high-fat diet; TG, triglyceride; FFA, free fatty acids.

P<0.01 vs. the control group

P<0.05

P<0.01 vs. the HFD group.

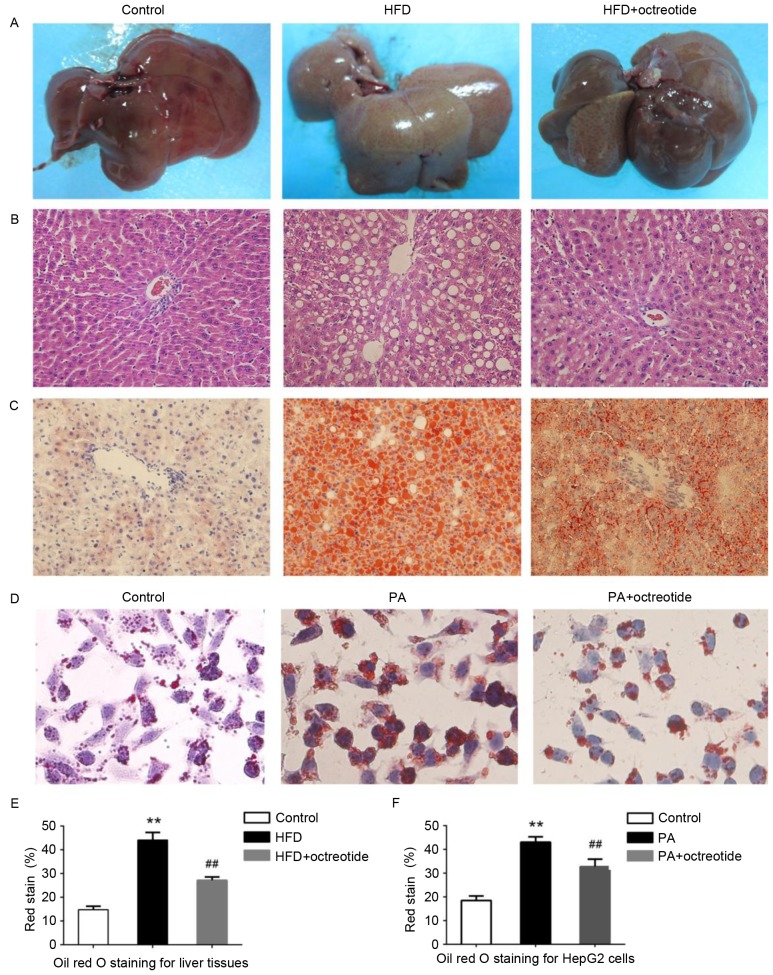

Octreotide improves fat degeneration in rats with HFD-induced obesity and lipid droplet accumulation in PA-treated HepG2 cells

Example livers collected from the rats are shown in Fig. 2A. Liver tissues from rats in the HFD group were slightly yellow in color and displayed marked steatosis. The livers of rats in the octreotide-treated and control groups were similar in macroscopic appearance (Fig. 2A). Hepatic histopathology analysis revealed that the obese rats displayed diffuse fat deposition, particularly near the central vein, which exhibited macrovesicular and microvesicular steatosis (Fig. 2B). No alterations in histopathological structure were observed in the livers collected from the control rats (Fig. 2B). Fat deposition was significantly improved by octreotide treatment (Fig. 2B). Oil Red O staining of liver tissues demonstrated marked lipid infiltration of hepatocytes in obese rats, as indicated by an increased number of red hepatocytes and higher IOD values when compared with the control rats (Fig. 2). Octreotide treatment significantly decreased lipid infiltration in obese rats (Fig. 2C). Similarly, octreotide intervention markedly alleviated PA-induced hepatocyte lipid droplet accumulation in HepG2 cells (Fig. 2D). In addition, the IOD values of the octreotide-treated group were lower when compared with the PA-treated group (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Effect of octreotide on HFD-induced hepatic steatosis in obese rats and on PA-induced hepatocyte lipid accumulation in HepG2 cells. (A) Appearance of rat livers in each experimental group. Hepatic steatosis was evaluated by (B) hematoxylin and eosin staining of the paraffin-embedded liver tissue sections (magnification, ×400), and by (C) Oil Red O staining of frozen liver tissue sections (magnification, ×400). (D) Lipid accumulation in HepG2 cells was assessed by Oil Red O staining (magnification, ×400). The IOD values of Oil Red O staining in the (E) liver of rats and (F) in HepG2 cells. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation of three independent experiments. **P<0.01 vs. the control group; ##P<0.01 vs. the HFD group or the PA group. HFD, high fat diet; PA, palmitate; IOD, integrated optical density.

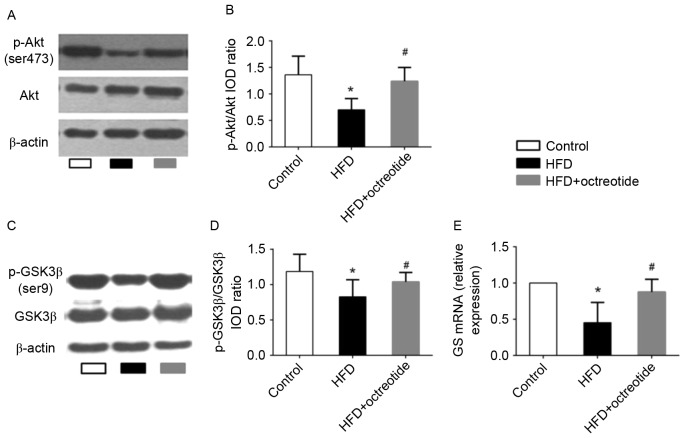

Effects of octreotide on the phosphorylation of Akt and GSK3β, and the mRNA levels of GS in the liver of obese rats

The Akt/GSK3β signaling pathway serves an important role in regulating hepatic glycogen synthesis (17). Therefore, western blotting was used to detect the protein expression levels of p-Akt and p-GSK3β, and RT-qPCR analysis was performed to determine the expression levels of GS mRNA in octreotide-treated obese rats in the present study. The results demonstrated that the expression of p-Akt and p-GSK3β in the HFD group was significantly lower when compared with the control group (0.70±0.21 vs. 1.36±0.35 and 0.83±0.29 vs. 1.19±0.24, respectively; P<0.05; Fig. 3). Octreotide treatment significantly increased the level of p-Akt and p-GSK3β protein expression when compared with the HFD group (1.24±0.26 vs. 0.70±0.21 and 1.04±0.27 vs. 0.83±0.29, respectively; P<0.05; Fig. 3). In addition, the results indicated that octreotide significantly reversed the HFD-induced reduction in GS mRNA levels (P<0.05; Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Octreotide promotes the phosphorylation of Akt and GSK3β and the expression of GS mRNA in rats with HFD-induced obesity. (A) Western blotting images of p-Akt (Ser473) and (B) quantification of band intensities. (C) Western blotting images of p-GSK3β (Ser9) and (D) quantification of band intensities. (E) The level of GS mRNA. Data presented as the mean ± standard deviation of three independent experiments. *P<0.05 vs. control group; #P<0.05 vs. HFD group. p-Akt, phosphorylated-Akt; p-GSK3β, phosphorylated-glycogen synthase kinase 3β; GS, glycogen synthase; HFD, high fat diet; IOD, integrated optical density.

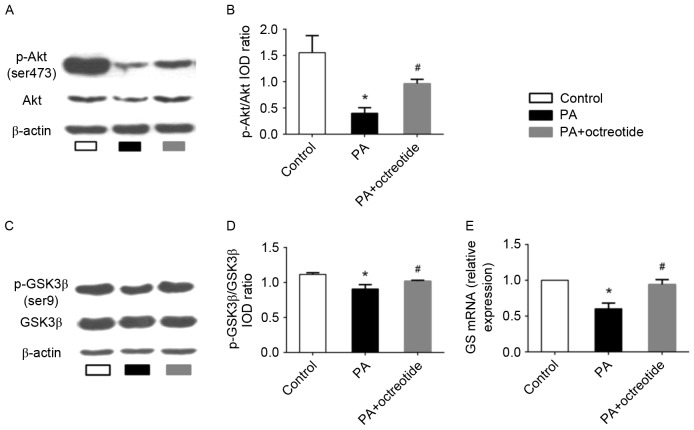

Octreotide reversed the PA-induced alterations in Akt and GSK3β phosphorylation and expression of GS mRNA in HepG2 cells

The results presented thus far indicate that octreotide may improve hepatic glycogen synthesis in obese rats. To further elucidate the mechanisms underlying the effects of octreotide on glycogen synthesis, the expression of p-Akt and p-GSK3β was determined by western blotting, and GS mRNA levels were examined by RT-qPCR analysis in PA-treated HepG2 cells. The western blotting results revealed that the levels of p-Akt and p-GSK3β in the PA group decreased by 74.2 and 18.7%, respectively, when compared with the control group (P<0.05; Fig. 4A-D). Following octreotide treatment, p-Akt and p-GSK3β levels increased by 140.8 and 12.2% when compared with the PA group, respectively (P<0.05; Fig. 4A-D). RT-qPCR analysis demonstrated that the expression of GS mRNA in the PA group was the lowest among the three groups (Fig. 4E). However, following octreotide treatment, GS mRNA levels were significantly increased when compared with the PA group (0.940±0.07 vs. 0.60±0.08; P<0.05; Fig. 4E).

Figure 4.

Expression of p-Akt and p-GSK3β protein, and GS mRNA levels in PA-treated HepG2 cells. (A) Western blotting images of p-Akt (Ser473) expression, and (B) quantification of band intensities. The PA group exhibited the lowest protein expression levels of p-Akt among the three groups. (C) Western blotting images of p-GSK3β (Ser9) expression, and (D) quantification of band intensities. The level of p-GSK3β expression in the PA group was lower when compared with the control group. However, octreotide administration inhibited the reduction by promoting GSK3β phosphorylation. (E) The downregulation of GS mRNA in the PA group was ameliorated by octreotide intervention. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation of three independent experiments. *P<0.05 vs. the control group; #P<0.05 vs. the PA group. p-Akt, phosphorylated-Akt; p-GSK3β, phosphorylated-glycogen synthase kinase 3β; GS, glycogen synthase; PA, palmitate; HFD, high fat diet; IOD, integrated optical density.

Discussion

Long-term consumption of a high-carbohydrate diet or HFD and limited physical activity leads to an energy imbalance, followed by obesity and an increased risk of obesity-associated diseases, such as NAFLD. Obesity, the critical risk factor for the development of NAFLD, is the primary cause of metabolic syndrome (18). Insulin resistance is considered to be the primary pathophysiological mechanism of metabolic syndrome (19). A number of studies have demonstrated that insulin resistance serves an important role in NAFLD development, and insulin resistance is thought to be the first symptom of NAFLD (20,21). Unfortunately, drugs that improve insulin sensitivity have demonstrated no marked effects on NAFLD thus far (22). In clinical medicine, octreotide is widely used for the treatment of acute pancreatitis and gastrointestinal bleeding. A previous study suggested that octreotide may reduce the weight of rats with HFD-induced obesity and improve metabolism and oxidative stress disorders (11). An additional previous study confirmed the function of octreotide in rats with diet-induced obesity, including weight loss, decreased blood glucose and insulin concentrations, and increased insulin sensitivity (23). The present study investigated the role of octreotide in the regulation of blood glucose and insulin concentrations, revealing that octreotide increases insulin sensitivity. The results of the ipGTT and ipITT further demonstrated that octreotide improves insulin sensitivity in HFD-induced obese rats.

Insulin resistance is closely associated with hepatic glycogen synthesis. The primary mechanism of reducing plasma glucose concentrations following a meal is the conversion of glucose into hepatic glycogen. Glycogen synthesis is mainly regulated by GSK3β and GS. Serum insulin increases GS activity by activating Akt, which subsequently phosphorylates GSK3β at Ser-9. p-GSK3β loses its ability to inhibit GS activity and thus promotes glycogen synthesis. This regulatory mechanism has been demonstrated in a previous study (7). Akt, a key enzyme in the insulin signaling pathway, mediates glucose metabolism via phosphorylation and activation of its downstream signaling molecules. Under insulin resistance conditions, insulin-regulated Akt/GSK signaling transduction is inhibited, and hepatic glycogen synthesis is decreased. A previous study reported that mice fed on a HFD developed insulin resistance, displayed increased levels of blood glucose and insulin, as well as decreased glycogen synthesis, p-Akt and p-GSK3β expression and GS mRNA levels. Hepatic glycogen synthesis was increased by promoting Akt and GSK3β phosphorylation and by increasing GS activity (24). Based on the results of the present study, octreotide increased p-Akt and p-GSK3β expression in rats with HFD-induced obesity and reversed the reduction in GS mRNA levels. A previous study demonstrated that increased insulin-induced gluconeogenesis and decreased glycogen synthesis are the major factors underlying the development of type 2 diabetes (25). Therefore, maintaining the balance between gluconeogenesis and glycogen synthesis may be an effective strategy to improve insulin resistance in the type 2 diabetes mouse model (25). In addition, a specific inhibitor of GSK3β, CHIR 98014, has demonstrated potential to treat type 2 diabetes and insulin resistance (26). These studies may explain the association between GSK3β activity, GS mRNA expression, hepatic glycogen synthesis and plasma glucose levels in obese rats.

The results of the present study indicated that octreotide improves hepatic glycogen synthesis in obese rats. In order to investigate the mechanisms underlying the effects of octreotide treatment on glycogen synthesis further, the protein expression levels p-Akt and p-GSK3β and GS mRNA levels were determined in an in vitro model of fatty liver disease induced by PA in HepG2 cells. The results demonstrated that octreotide significantly increased p-Akt and p-GSK3β protein expression and GS mRNA levels. Similar to the HepG2 PA-induced insulin resistance model, a previous study revealed that hepatocyte glycogen synthesis and glycogen content increased via activation of the Akt/GSK signaling pathway (25).

GSK3β is a key enzyme that modulates the insulin signaling pathway via inhibition of GS. In theory, p-GSK3β expression should increase following intraperitoneal injection of insulin in insulin-sensitive individuals, followed by an elevation in serum insulin concentration (3). However, the results of the present study demonstrated that the expression of p-GSK3β decreased in obese rats, which may have occurred as a result of impaired insulin signal transduction. Lu et al (27) revealed that mice that lose the expression of Akt1 and Akt2 in the liver develop insulin resistance and impaired glucose tolerance. The promotion of Akt phosphorylation restores insulin signal transduction and improves metabolic disorders in obese mice (28). The present study indicated that octreotide treatment improved hepatic glycogen synthesis in obese rats via the Akt/GSK signaling pathway; however, further investigation of the mechanisms underlying these effects is required.

The potential side effects of octreotide are gastrointestinal reactions, including anorexia, cramps, steatorrhea, liquid stools and diarrhea (23). However, during the period of octreotide treatment in the present study, no obvious signs of discomfort in the octreotide-treated rats were observed; in fact these rats displayed normal activity and eating behaviors. In addition, none of the rats exhibited any evidence of diarrhea or steatorrhea during the study period. Therefore, the authors concluded that octreotide administration in the present study demonstrated no obvious side effects in the rats, at least for the period tested.

In conclusion, the results of the present study demonstrated that octreotide improves glycogen synthesis in rats with HFD-induced obesity and decreases FPG concentration. In addition, octreotide appears to mediate these effects by increasing GS activity via induction of GSK3β phosphorylation. Based on the results of the current study, octreotide may potentially be an effective therapeutic strategy for HFD-induced obesity and obesity-associated metabolic disorders.

Acknowledgements

The present study was supported by the National Natural Sciences Foundation of China (grant no. 30870919) and the Sichuan Provincial Department of Science and Technology (grant no. 2010SZ0176).

References

- 1.Yu SJ, Kim W, Kim D, Yoon JH, Lee K, Kim JH, Cho EJ, Lee JH, Kim HY, Kim YJ, Kim CY. Visceral obesity predicts significant fibrosis in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Medicine (Baltimore) 2015;94:e2159. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000002159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tolman KG, Fonseca V, Dalpiaz A, Tan MH. Spectrum of liver disease in type 2 diabetes and management of patients with diabetes and liver disease. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:734–743. doi: 10.2337/dc06-1539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Perry RJ, Samuel VT, Petersen KF, Shulman GI. The role of hepatic lipids in hepatic insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. Nature. 2014;510:84–91. doi: 10.1038/nature13478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fruci B, Giuliano S, Mazza A, Malaguarnera R, Belfiore A. Nonalcoholic fatty liver: A possible new target for type 2 diabetes prevention and treatment. Int J Mol Sci. 2013;14:22933–22966. doi: 10.3390/ijms141122933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schinner S, Scherbaum WA, Bornstein SR, Barthel A. Molecular mechanisms of insulin resistance. Diabet Med. 2005;22:674–682. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2005.01566.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nordlie RC, Foster JD, Lange AJ. Regulation of glucose production by the liver. Annu Rev Nutr. 1999;19:379–406. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.19.1.379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Taniguchi CM, Emanuelli B, Kahn CR. Critical nodes in signaling pathways: Insights into insulin actio. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:85–96. doi: 10.1038/nrm1837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ishikawa M, Yoshida K, Okamura H, Ochiai K, Takamura H, Fujiwara N, Ozaki K. Oral Porphyromonas gingivalis translocates to the liver and regulates hepatic glycogen synthesis through the Akt/GSK-3β signaling pathway. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1832:2035–2043. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2013.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim KM, Lee KS, Lee GY, Jin H, Durrance ES, Park HS, Choi SH, Park KS, Kim YB, Jang HC, Lim S. Anti-diabetic efficacy of KICG1338, a novel glycogen synthase kinase-3β inhibitor and its molecular characterization in animal models of type 2 diabetes and insulin resistance. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2015;409:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2014.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van Op den Bosch J, Adriaensen D, Van Nassauw L, Timmermans JP. The role(s) of somatostatin, structurally related peptides and somatostatin receptors in the gastrointestinal tract: A review. Regul Pept. 2009;156:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2009.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li W, Shi YH, Yang RL, Cui J, Xiao Y, Wang B, Le GW. Effect of somatostatin analog on high-fat diet-induced metabolic syndrome: Involvement of reactive oxygen species. Peptides. 2010;31:625–629. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2009.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li M, Ye T, Wang XX, Li X, Qiang O, Yu T, Tang CW, Liu R. Effect of octreotide on hepatic steatosis in diet-induced obesity in rats. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0152085. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0152085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gupte AA, Liu JZ, Ren Y, Minze LJ, Wiles JR, Collins AR, Lyon CJ, Pratico D, Finegold MJ, Wong ST, et al. Rosiglitazone attenuates age- and diet-associated nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in male low-density lipoprotein receptor knockout mice. Hepatology. 2010;52:2001–2011. doi: 10.1002/hep.23941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sodhi K, Puri N, Favero G, Stevens S, Meadows C, Abraham NG, Rezzani R, Ansinelli H, Lebovics E, Shapiro JI. Fructose mediated non-alcoholic fatty liver is Attenuated by HO-1-sirt1 module in murine hepatocytes and mice fed a high fructose diet. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0128648. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0128648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 15.López-Terrada D, Cheung SW, Finegold MJ, Knowles BB. Hep G2 is a hepatoblastoma-derived cell line. Hum Pathol. 2009;40:1512–1515. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2009.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ishikawa M, Yoshida K, Okamura H, Ochiai K, Takamura H, Fujiwara N, Ozaki K. Oral Porphyromonas gingivalis translocates to the liver and regulates hepatic glycogen synthesis through the Akt/GSK-3β signaling pathway. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1832:2035–2043. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2013.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kumashiro N, Erion DM, Zhang D, Kahn M, Beddow SA, Chu X, Still CD, Gerhard GS, Han X, Dziura J, et al. Cellular mechanism of insulin resistance in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:16381–16385. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1113359108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gan L, Meng ZJ, Xiong RB, Guo JQ, Lu XC, Zheng ZW, Deng YP, Luo BD, Zou F, Li H. Green tea polyphenol epigallocatechin-3-gallate ameliorates insulin resistance in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease mice. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2015;36:597–605. doi: 10.1038/aps.2015.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Souza-Mello V. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors as targets to treat non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. World J Hepatol. 2015;7:1012–1019. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v7.i8.1012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hwang KA, Hwang YJ, Kim GR, Choe JS. Extracts from Aralia elata (Miq) Seem alleviate hepatosteatosis via improving hepatic insulin sensitivity. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2015;15:347. doi: 10.1186/s12906-015-0871-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Musso G, Gambino R, Cassader M, Pagano G. A meta-analysis of randomized trials for the treatment of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2010;52:79–104. doi: 10.1002/hep.23623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huang W, Liu R, Ou Y, Li X, Qiang O, Yu T, Tang CW. Octreotide promotes weight loss via suppression of intestinal MTP and apoB48 expression in diet-induced obesity rat. Nutrition. 2013;29:1259–1265. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2013.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang Y, Li W, Liu Y, Li Y, Gao L, Zhao JJ. Alpha-lipoic acid attenuates insulin resistance and improves glucose metabolism in high fat diet-fed mice. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2014;35:1285–1292. doi: 10.1038/aps.2014.64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu TY, Shi CX, Gao R, Sun HJ, Xiong XQ, Ding L, Chen Q, Li YH, Wang JJ, Kang YM, Zhu GQ. Irisin inhibits hepatic gluconeogenesis and increased glycogen synthesis via the PI3K/Akt pathway in type 2 diabetic mice and hepatocytes. Clin Sci (Lond) 2015;129:839–850. doi: 10.1042/CS20150009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.MacAulay K, Woodgett JR. Targeting glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK-3) in the treatment of Type 2 diabetes. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2008;12:1265–1274. doi: 10.1517/14728222.12.10.1265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lu M, Wan M, Leavens KF, Chu Q, Monks BR, Fernandez S, Ahima RS, Ueki K, Kahn CR, Birnbaum MJ. Insulin regulates liver metabolism in vivo in the absence of hepatic Akt and Foxo1. Nat Med. 2012;18:388–395. doi: 10.1038/nm.2686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ozcan L, de Cristina Souza J, Harari AA, Backs J, Olson EN, Tabas I. Activation of calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II in obesity mediates suppression of hepatic insulin signaling. Cell Metab. 2013;18:803–815. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]