Abstract

MitoNEET (CISD1) is a 2Fe-2S iron-sulfur cluster protein belonging to the zinc-finger protein family. Recently mitoNEET has been shown to be a major role player in the mitochondrial function associated with metabolic type diseases such as obesity and cancers. The anti-diabetic drug pioglitazone and rosiglitazone were the first identified ligands to mitoNEET. Since little is known about structural requirements for ligand binding to mitoNEET, we screened a small set of compounds to gain insight into these requirements. We found that the thiazolidinedione (TZD) warhead as seen in rosiglitazone was not an absolutely necessity for binding to mitoNEET. These results will aid in the development of novel compounds that can be used to treat mitochondrial dysfunction seen in several diseases.

Keywords: Mitochondria, Bioenergetics, Glitazones, Type II diabetes

MitoNEET (CISD1) is a recently discovered protein found on the outer surface of mitochondria discovered by investigations of the off target pharmacological effects of the anti-diabetic drug pioglitazone. 1,2 This protein belongs to a novel family of NEET proteins that contain 2Fe-2S clusters and are evolutionary conserved in several organisms including Caenorhabditis elegans, bacteria, and plants. MitoNEET belongs to the CDGSH-type zinc finger protein family, although it contains iron instead of the expected zinc, and has the characteristic amino acid sequence Asn-Glu-Glu-Thr.3–5 This family of proteins includes the genes CISD1 (mitoNEET), CISD2 (NAF-1, miner1) and CISD3 (miner2). In mitoNEET the iron-sulfur clusters are found to be coordinated in a 3Cys:1His configuration, which several groups have suggested act as a redox sensor for mitochondria to respond to oxidative changes in the cellular environment. The iron-sulfur cluster has been shown to be labile at pH < 8, leading to a loss of the cluster and transfer to other proteins in the cell such as anamorsin. The biological role of mitoNEET remains to be fully elucidated but it has been indicated to play an important role in diabetes and obesity, as well as in breast cancer cell proliferation. In obesity, for example, it was found that when mitoNEET is overexpressed in the adipose tissue of ob/ob genetic mice, systemic inflammation markers are significantly decreased in concert with a reduction in oxidative stress markers such as reactive oxygen species (ROS).6 These studies suggests that mitoNEET may constitute a novel drug target against mitochondrial dysfunction possibly impacting several disease states.2

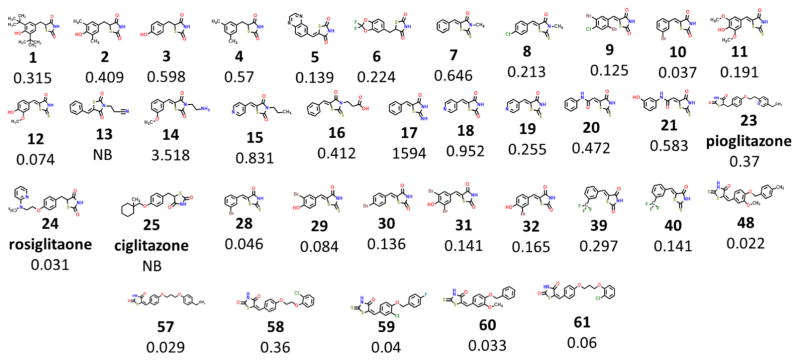

The structure and function of mitoNEET has garnered a lot of attention in the past few years, but lacking is a comprehensive study showing the classes of compounds that can bind to mito-NEET. Currently known ligands that bind with mitoNEET belong to the thiazolidinedione (TZD or glitazones) family with NL-1 1, pioglitazone 23, rosiglitazone 24 and (Fig. 1) as the best described.1,7 The current study builds on our earlier work that described the structure–activity relationships (SAR) for a small set of compounds and their binding to mitoNEET8 and expands our knowledge space of chemical interaction with mitoNEET.

Figure 1.

TZD ligands which bind to mitoNEET. Binding affinity is shown in microM (Ki). Abbreviation: non-binding (NB).

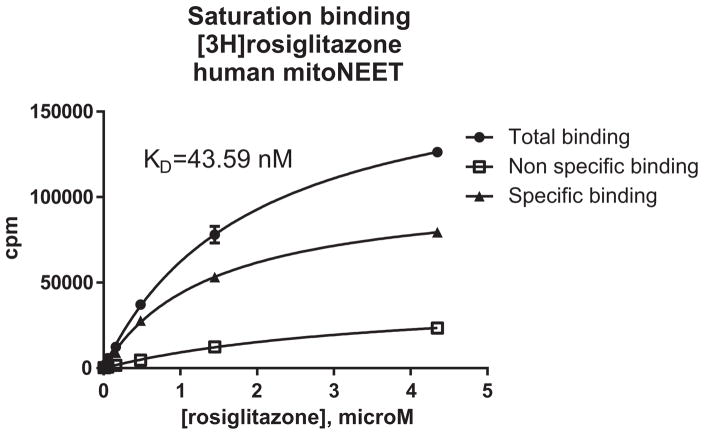

MitoNEET was first discovered from a photo-affinity labeling via a derivative of pioglitazone. Pioglitazone belongs to the glitazone chemical class due to its thiazolidinedione (TZD) warhead moiety.1 Although several studies have been published in recent years regarding the physiologic role of mitoNEET, few papers have appeared that focused on ligand binding characteristics of mito-NEET-associated compounds. This study was therefore initiated to fill that gap in knowledge. Utilizing a HTS screening assay, that we described previously,8 we expanded the compound set to explore both effects of the TZD warhead as well as other compounds to identify new scaffolds that might be able to bind to mitoNEET.8 Data on compound binding to human recombinant mitoNEET is given in Table 1. The Ki values were derived from the Cheng–Prusoff equation where the KD for rosiglitazone was found to be 44 nM (Fig. 2).

Table 1.

Binding affinity of compounds to human recombinant mitoNEET. [3H]rosigltizone was used as radio-label*

| # | Name/ID | IC50 (μM) | Ki (μM) | # | Name/ID | IC50 (μM) | Ki (μM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | NL-1 | 7.36 | 0.315 | 45 | Pomalidomide | NB | NB |

| 2 | NL-2 | 9.56 | 0.409 | 46 | 7917584 | 3.3 | 0.141 |

| 3 | NL-3 | 14 | 0.598 | 47 | Acyclovir | NB | NB |

| 4 | NL-4 | 13.34 | 0.57 | 48 | 6209863 | 0.518 | 0.022 |

| 5 | NL-5 | 3.26 | 0.139 | 49 | Stiripentol | NB | NB |

| 6 | NL-6 | 5.23 | 0.224 | 50 | 4-Amino-1,8-naphthalimide | 264 | 11.282 |

| 7 | NL-7 | 15.12 | 0.646 | 51 | Triapine | 9.078 | 0.388 |

| 8 | NL-8 | 4.98 | 0.213 | 52 | Suramin | NB | NB |

| 9 | NL-9 | 2.93 | 0.125 | 53 | Bosutinib | NB | NB |

| 10 | NL-10 | 0.86 | 0.037 | 54 | Nitrofurantoin | 19.1 | 0.816 |

| 11 | NL-11 | 4.47 | 0.191 | 55 | Dantrolene | 48.33 | 2.065 |

| 12 | NL-12 | 1.73 | 0.074 | 56 | CCCP | 35.04 | 1.497 |

| 13 | NL-13 | NB | NB | 57 | 6636424 | 0.6861 | 0.029 |

| 14 | NL-14 | 82.32 | 3.518 | 58 | 6373721 | 0.8389 | 0.036 |

| 15 | NL-15 | 19.44 | 0.831 | 59 | 7320244 | 0.9454 | 0.04 |

| 16 | NL-16 | 9.63 | 0.412 | 60 | 5472855 | 0.7701 | 0.033 |

| 17 | NL-17 | 37320 | 1594.88 | 61 | 6634507 | 1.399 | 0.06 |

| 18 | NL-18 | 22.27 | 0.952 | 62 | 5119666 | 1.829 | 0.078 |

| 19 | NL-19 | 5.97 | 0.255 | 63 | 7138125 | 7.983 | 0.341 |

| 20 | NL-20 | 11.05 | 0.472 | 64 | Nitrofurazone | NB | NB |

| 21 | NL-21 | 13.65 | 0.583 | 65 | Furazolidone | NB | NB |

| 22 | Resveratrol-3-sulfate | 3.36 | 0.144 | 66 | Furaltadone | NB | NB |

| 23 | Pioglitazone | 8.65 | 0.37 | 67 | C10d | NB | NB |

| 24 | Rosiglitazone | 0.731 | 0.031 | 68 | Dorzolamide | NB | NB |

| 25 | NL-22 | NB | NB | 69 | Chloro-imidazole | NB | NB |

| 26 | Curcumin | 2.36 | 0.101 | 70 | Diclofenac | NB | NB |

| 27 | Kaempferol | 3.1 | 0.132 | 71 | Metformin | NB | NB |

| 28 | NL-23 | 1.067 | 0.046 | 72 | Naproxen | NB | NB |

| 29 | NL-24 | 1.964 | 0.084 | 73 | 5-Azacytidine | NB | NB |

| 30 | NL-25 | 3.18 | 0.136 | 74 | L-732,138 | NB | NB |

| 31 | NL-26 | 3.289 | 0.141 | 75 | Homotaurine | NB | NB |

| 32 | NL-27 | 3.858 | 0.165 | 76 | 7722368 | 9.657 | 0.413 |

| 33 | NL-28 | 0.91 | 0.039 | 77 | 5472855 | 1.485 | 0.063 |

| 34 | NL-29 | NB | NB | 78 | GSK-LSD1 | 3.454 | 0.148 |

| 35 | NL-30 | NB | NB | 79 | Tryprostatin-A | 3.387 | 0.145 |

| 36 | NL-31 | 1.22 | 0.052 | 80 | Doxorubicin | 80.76 | 3.451 |

| 37 | NL-32 | 0.148 | 0.006 | 81 | Chloroquine | NB | NB |

| 38 | AG104 | 1.8 | 0.077 | 82 | Ursodiol | 26.54 | 1.134 |

| 39 | NL-33 | 6.94 | 0.297 | 83 | ATP | NB | NB |

| 40 | NL-34 | 3.307 | 0.141 | 84 | TC1 | NB | NB |

| 41 | Furosemide | 53.46 | 2.285 | 85 | Methamphetamine | NB | NB |

| 42 | α-Hydroxy-cinnamic acid | 40 | 1.709 | 86 | Retigabine | NB | NB |

| 43 | Glibenclamide | 39.1 | 1.671 | 87 | Gemfibrozil | 170.6 | 7.291 |

| 44 | Dichloroacetate | NB | NB |

Non-binding (NB).

Figure 2.

Determination of affinity for rosiglitazone to human recombinant mitoNEET. [3H]rosiglitazone was used a label. Human recombinant mitoNEET was attached via a His-tag to SPA beads, and binding determined from displacement of [3H]rosiglitazone by unlabeled rosiglitazone.

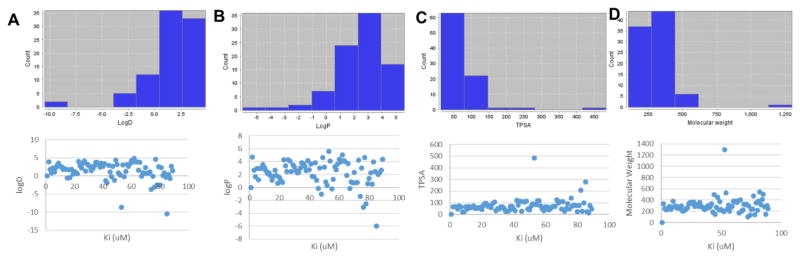

Figure 3 shows properties of the compounds tested in this study. The majority of the compounds had a molecular weight less than 450 Da. The logD, logP and total polar surface area (TPSA) were also determined and the majority of compounds were found to adhere to the rules of 5.9 No apparent correlation was seen between each chemical property and the binding affinity (Ki).

Figure 3.

Chemical properties of the compounds evaluated in this study. Shown are: (A) logD, (B) logP, (C) total polar surface area (TPSA) and (D) molecular weight. Below the count graphs, a linear regression plot between Ki (microM) and the chemical attribute.

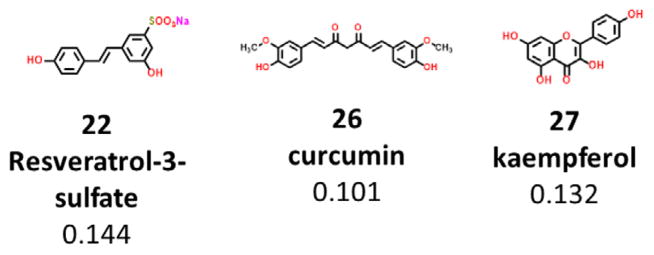

A previous study done by Bieganski et al. showed that mito-NEET may bind to polyphenolic compounds from natural product sources.10 We also found that the active metabolite of resveratrol, resveratrol-3-sulfate 22, can bind to mitoNEET with a Ki of 144 nM; although the parent compound resveratrol did not bind to mito-NEET in our studies.11 Other polyphenolic compounds found to have mitochondrial functional effects were tested to see whether they can bind to mitoNEET as well. We tested the natural compound curcumin 26, which is isolated from the Indian spice turmeric, and found it to bind to mitoNEET at a Ki of 101 nM. The flavonoid kaempferol 27, shown to have mitochondrial protective effects, was found to bind to mitoNEET at a Ki of 132 nM12 (Figs. 4–6).

Figure 4.

Natural products which bind to mitoNEET. Binding affinity is shown in microM (Ki). Abbreviation: non-binding (NB).

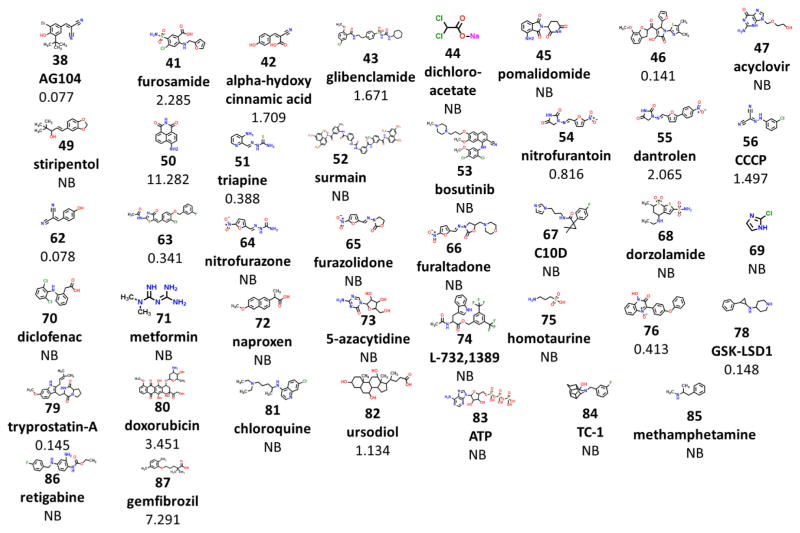

Figure 6.

FDA approved compounds and their affinity for mitoNEET. Binding affinity is shown in microM (Ki). Abbreviation: non-binding (NB).

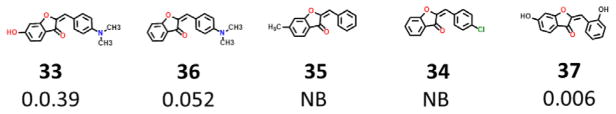

Based on the work previously done by us on the flavonoid from the plant Rhus verniciflua sulfuretin13 was also found that the benzofuran aurones bind to mitoNEET with varied affinity. For instance, compound 34 and 35 were non-binders while 36 bound to mitoNEET at a Ki of 52 nM and 37 with a Ki of 6 nM. This indicates that for aurones there are specific requirements for binding to mitoNEET to achieve optimum binding potency.

Since TZD warheads are the most well characterized mitoNEET ligand chemotype, we wanted to explore if opening of the TZD ring would perturb mitoNEET binding. A range of affinities can be seen with these TZD-type compounds, as the Ki values varied dramatically between the nanomolar to high micromolar range. Since the TZD warhead is constant in these compounds it appears the ability to bind to mitoNEET is largely dependent on the aromatic substituted moieties in the compounds. We tested a series of compounds and found that 42, α-hydroxycinnamic acid, with a Ki of 1.7 μM was only slightly less potent than a similar TZD compound, e.g., compound 3, suggesting that the phenol group, present in both 3 and 42, can have significant impact on potency. Similarly, nitrile containing compounds such as compound 56, CCCP with a Ki of 1.49; compound 38, AG104 with a Ki of 77 nM; and compound 62 with a Ki of 78 nM are all able to bind to mitoNEET without the TZD warhead as previously suggested but that phenols also seem to contribute to binding; 38 and 62 are substantially more potent than 56, which lacks a phenol. Additionally, compound 3-AP 51 displayed high affinity with a Ki of 388, which supports our hypothesis that the TZD warhead could be replaced with other moieties. Also of interest was that nitrofurantoin 54, an antibiotic used for urinary tract infections, binds to mitoNEET with a Ki of 816 nM while structurally related compounds such as furazolidone 65 and furaltadone 66 and dorzolamide 68, ere non-binders. The structurally similar muscle relaxant dantrolene 55 has a Ki of 2.06 μM, suggesting the additional aromatic ring compared to nitrofurantoin positively influences binding to mitoNEET.

Several other FDA approved drugs were tested for mitoNEET binding, although most were found to be non-binders. We did however find the diuretic compound furosemide 41 was able to bind to mitoNEET with a Ki of 2.28 μM. The non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs diclofenac 70 and naproxen 72 were found to be non-binders. Other type II anti-diabetic drugs were found to bind with mitoNEET such as glibenclamide (43: Ki of 1.67 mM) whereas metformin 71 did not bind to mitoNEET. Considering the different functional effects these compounds have shown on mitochondria,14,15 they may be useful as pharmacological tools to fully elucidate mitoNEET’s mitochondrial activity.

In conclusion we show here a set of compounds that have been screened for binding to mitoNEET. We found the TZD warhead of the glitazones can be substituted for different structural groups, which may have the benefit of reducing side effect profiles seen before with TZDs.1,2 MitoNEET represents a novel protein drug target for the treatment of metabolic diseases where mitochondrial dysfunction is thought to play a critical role in the pathology, ranging from obesity to Parkinson’s disease thereby with the promise of yielding novel drugs.

Figure 5.

Benzofuran aurones which bind to mitoNEET. Binding affinity is shown in microM (Ki). Abbreviation: non-binding (NB).

Acknowledgments

This work was funded in part by the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research to WJG. The project described was supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, U54GM104942. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

References and notes

- 1.Colca JR, McDonald WG, Waldon DJ, Leone JW, Lull JM, Bannow CA, Lund ET, Mathews WR. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2004;286:E252. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00424.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Geldenhuys WJ, Leeper TC, Carroll RT. Drug Discovery Today. 2014;19:1601. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2014.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lin J, Zhou T, Ye K, Wang J. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:14640. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702426104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Paddock ML, Wiley SE, Axelrod HL, Cohen AE, Roy M, Abresch EC, Capraro D, Murphy AN, Nechushtai R, Dixon JE, Jennings PA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:14342. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707189104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wiley SE, Murphy AN, Ross SA, van der Geer P, Dixon JE. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:5318. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701078104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kusminski CM, Holland WL, Sun K, Park J, Spurgin SB, Lin Y, Askew GR, Simcox JA, McClain DA, Li C, Scherer PE. Nat Med. 2012;18:1539. doi: 10.1038/nm.2899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Geldenhuys WJ, Funk MO, Barnes KF, Carroll RT. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2010;20:819. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2009.12.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Geldenhuys WJ, Funk MO, Awale PS, Lin L, Carroll RT. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2011;21:5498. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2011.06.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lipinski CA, Lombardo F, Dominy BW, Feeney PJ. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2001;46:3. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(00)00129-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bieganski RM, Yarmush ML. J Mol Graph Model. 2011;29:965. doi: 10.1016/j.jmgm.2011.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arif W, Xu S, Isailovic D, Geldenhuys WJ, Carroll RT, Funk MO. Biochemistry. 2011;50:5806. doi: 10.1021/bi200546s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guo Z, Liao Z, Huang L, Liu D, Yin D, He M. Eur J Pharmacol. 2015;761:245. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2015.05.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Geldenhuys WJ, Funk MO, Van der Schyf CJ, Carroll RT. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2012;22:1380. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2011.12.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fernandes MA, Santos MS, Moreno AJ, Duburs G, Oliveira CR, Vicente JA. J Biochem Mol Toxicol. 2004;18:162. doi: 10.1002/jbt.20022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Andrzejewski S, Gravel SP, Pollak M, St-Pierre J. Cancer Metab. 2014;2:12. doi: 10.1186/2049-3002-2-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]