Abstract

Background

Gain of function (GOF) mutations in the human Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription 1 (STAT1) manifest in immunodeficiency and autoimmunity with impaired T helper (TH) 17 cell differentiation and exaggerated responsiveness to types I and II interferon. Allogeneic bone marrow transplantation has been attempted in severely affected patients but outcomes have been poor.

Objective

We sought to define the effect of increased STAT1 activity on T helper cell polarization and to investigate the therapeutic potential of ruxolitinib in treating autoimmunity secondary to STAT1 GOF mutations.

Methods

We used in vitro polarization assays as well as phenotypic and functional analysis of STAT1-mutated patient cells.

Results

We report on a child with a novel mutation in the linker domain of STAT1 who suffered from life-threatening autoimmune cytopenias and chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis. Naïve patient lymphocytes displayed increased TH1 and T follicular helper (TFH) cell as well as suppressed TH17 cell responses. The mutation augmented cytokine-induced STAT1 phosphorylation without affecting dephosphorylation kinetics. Treatment with the Janus kinase (JAK) 1/2 inhibitor ruxolitinib reduced hyper-responsiveness to types I and II interferon, normalized TH1 and TFH cell responses, improved TH17 differentiation, cured mucocutaneous candidiasis and maintained remission of immune mediated cytopenias.

Conclusions

Autoimmunity and infection due to STAT1 GOF mutations is caused by dysregulated T helper cell responses. JAK inhibitor therapy could represent an effective targeted treatment for long-term disease control in severely affected patients for whom hematopoietic stem cell transplantation is not available.

Keywords: STAT1 gain of function, Interferon-γ, ruxolitinib, autoimmunity, T helper cell type 1, T helper cell type 17, T follicular helper cell, T helper cell polarization

Graphical abstract

Introduction

Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription 1 (STAT1) is a member of the STAT family of transcription factors that plays a key role in the cellular response to interferons (IFN), and is a central component in many other signaling pathways including interleukins, growth factors and hormones. In response to extracellular receptor stimulation, Janus kinase (JAK) activation leads to phosphorylation of cytoplasmic STAT1, followed by homodimerization or heterodimerization with other phosphorylated STAT family members. The dimers translocate into the nucleus and bind designated promoter elements to activate transcription of their respective target genes.1-3

STAT1 is the target of loss and gain of function (LOF/GOF) mutations. Whereas the former are associated with susceptibility to mycobacterial and/or viral infections, the latter give rise to a mixed phenotype of autoimmunity, mucocutaneous candidiasis and invasive fungal infections, related to augmented T helper cell type 1 (TH1) and diminished T helper cell type 17 (TH17) responses.4-9 STAT1 GOF mutations prompt a signal-induced increase in phosphorylated STAT1 and amplified transcription of IFN responsive genes, which lead to autoimmunity.5, 6, 10 Delayed dephosphorylation with ensuing accumulation of phospho-STAT1 in the nucleus has been proposed as mechanistic basis in most reported cases.1, 6, 11-15 How increased STAT1 activity compromises TH17 immunity to result in chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis and other invasive fungal and viral infections is less well understood.12, 16, 17 Excessive production of IFNs, IL-27 and Programmed Death (PD) 1 ligand may directly impair TH17 cell differentiation.18, 19 Alternatively, predominance of STAT1 over STAT3 signaling may deviate the response to IL-6, IL-21 and IL-23 away from STAT3, which normally mediates TH17 cell development.1, 18

The clinical management of patients with STAT1 GOF mutations remains challenging.20-22 In particular, controlling autoimmunity is difficult as conventional immunosuppression adds to the already increased risk of infections. Therapy-refractory or life-threatening disease is considered a non-canonical indication for allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, however, the immune phenotype of STAT1 GOF mutations amplifies the transplant-related risk for uncontrolled infections and graft versus host disease, contributing further to the poor prognosis.21, 23

Lui et al. were the first to provide proof of principle that Janus Kinase (JAK) inhibitors can successfully treat STAT1-mediated hyper-responsiveness to IFN in patients with vascular and pulmonary syndrome due to mutations in TMEM173, encoding the stimulator of interferon genes (STING).24 Higgins et al. reported hair regrowth in a patient with alopecia areata secondary to a STAT1 GOF mutation after treatment with ruxolitinib.10 Most recently, Mössner et al. observed improvement of chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis on ruxolinib and a reactive increase in IL-17A/F.25 Here we describe the immune-phenotypic analysis of a patient with life-threatening autoimmune cytopenias and a novel GOF mutation in the linker domain of STAT1. Importantly, in addition to increasing TH1 and suppressing TH17 cell differentiation, the augmented STAT1 activity dysregulated TFH cell responses. This finding was corroborated in a different patient with known STAT1T385M GOF mutation in the DNA-binding domain who presented solely with chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis and opportunistic infections but without clinical evidence of autoimmunity.13, 26, 27 Long-term treatment with the JAK inhibitor ruxolitinib decreased the elevated STAT1 phosphorylation, reversed the dysregulated TH1 and TFH development, improves the previously impaired TH17 response, and enabled effective control of the autoimmune cytopenias. This is the first report demonstrating mechanistic evidence that pharmacologic manipulation of the JAK-STAT pathway in patients with STAT1 GOF mutation leads to reversal of the immune dysregulation phenotype, and provides proof of principle that JAK-inhibitors are not only effective in treating active autoimmune disease and immunodeficiency secondary to hyper-responsiveness to STAT1 but in reversing the aberrant priming of naïve cells, thereby maintaining long-term disease control and sustained remission.

Methods

Patient and healthy subjects

All study participants were recruited with written informed consent approved by the Boston Children's Hospital institutional review board.

Pharmacotherapy

The IL-1 receptor antagonist anakinra (Kineret®) was administered intravenously twice daily at a dose of 100 mg. Four infusions with equine anti-thymocyte globulin (ATG, Atgam®) were given intravenously at a dose of 40 mg/kg body weight per infusion 24 hours apart. Supportive therapy during the infusions consisted of acetaminophen, diphenhydramine and methylpredinisolone. Treatment with intravenous cyclosporine A (SandIMMUNE®) was initiated on day 1 of ATG-therapy at a dose of 4 mg/kg body weight per day and titrated to a serum level of 175-250 mcg/L. Route of administration was converted to oral after 4 weeks, maintaining the same serum target level. Eculizumab (Soliris®) was given intravenously at a dose of 600 mg per infusion. Only one infusion was administered due to lack of efficacy. Supportive therapy during the infusion consisted of acetaminophen, diphenhydramine and methylprednisolone. The patient received a meningococcal vaccination prior to treatment as well as meningococcal prophylaxis with azithromycin for 6 months post infusion. Rituximab (Rituxan®) was given intravenously at a dose of 375 mg/m2 body surface area (BSA) once weekly for 4 consecutive weeks. Supportive therapy during the infusions consisted of acetaminophen, diphenhydramine and methylprednisolone. Treatment with ruxolitinib (Jakafi®) was initiated at a low dose of 5 mg/m2 BSA once daily due to concomitant use of other CYP3A4-inhibiting medications. The ruxolitinib dose was escalated until the amount of phospo-STAT1 induced in the patient's CD4+ T cells was equal to phospho-STAT1 in the healthy control cells. The final therapeutic ruxolitinib dose was 10 mg/m2 BSA administered orally daily in two divided doses.

STAT1 sequencing

Exons 3 to 23 of STAT1, including exon/intron boundaries, were amplified from genomic DNA by PCR and sequenced bidirectionally using dye-terminator chemistry. PCR-amplification of exon 20 was carried out using the following primers: STAT1E20_F (GATAAGAGCGGGGAGGG) and STAT1E20_R (TGAAGCTGGACTCAGGC). The mutation was predicted to be deleterious by SIFT and Polyphen2.28, 29

Protein modeling

The STAT1 E545K mutant structure was generated by SWISS-MODEL using STAT1 structures (PDB code: 1YVL and 1BF5).30-33 Structural alignment was performed in Coot and molecular representation was displayed in Pymol.34

Antibodies and flow cytometry

Monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) to the following human proteins were used for staining:

eBioscience

CD3 (UCHT1), CD4 (RPA-T4), CD8 (RPA-T8), CD45RA (HI100), CCR7 (G043H7), ICOS (C398.4A), PD1 (eBioJ105), CXCR5 (MU5UBEE), P-STAT1 (KIKSI0803), P-STAT3 (LUVNKLA)

Biolegend

IL-17 (BL168), IFN-γ (4S.B3), CCR6 (G034E3), CXCR3 (G025H7)

R&D Systems

STAT1 (246523). Appropriate isotype controls were used in parallel. PBMCs were incubated with mAbs against surface proteins for 30 min on ice.

Intracellular STAT1 staining

STAT1 staining was performed using an eBioscience fixation/permeabilization kit according to the manufacturer's instructions.

P-STAT1 and P-STAT3 staining

PBMCs were stimulated in complete medium for 20 min with appropriate cytokines; human IFN-β (Miltenyi; 20 ng/ml), IFN-γ or IL-21 (Peprotech; 20 ng/ml). Subsequently, PBMCs were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde for 20 min on ice, permeabilized with 90% methanol for 30 min on ice and stained using CD3, CD4, P-STAT1 and P-STAT3 mAbs in PBS for 30 min.

Ex-vivo cytokine detection

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated from whole blood by centrifugation over a Ficoll gradient and stimulated in complete medium in the presence of anti-CD2/CD3/CD28 beads (Miltenyi) and 100 units/mL recombinant human IL-2 (Peprotech) for 2 days. Subsequently, cell suspensions were incubated with phorbol myristate acetate (PMA) (Sigma-Aldrich; 50 ng/mL), ionomycin (Sigma-Aldrich; 500 ng/mL) and GolgiPlug™ (BD Biosciences; according to manufacturers instructions) in complete medium for 4 h before surface staining. Permeabilization and intracellular IFN-γ and IL-17 staining was carried out using an eBioscience Fixation/Permeabilization kit as described above. Data were collected with an LSRFortessa™ cytometer (BD Biosciences) and analyzed with FlowJo software (Tree Star, Inc.).

JAK inhibitor treatment in vitro

PBMCs were incubated for 4h in the presence of different concentrations of ruxolitinib, primarily a JAK1/2 inhibitor (Selleckchem; 10 nM, 100 nM), and tofacitinib, predominantly a JAK3 inhibitor (Sigma-Aldrich; 10 nM, 100 nM) or vehicle (Dimethyl Sulfoxide) alone prior to stimulation with recombinant human IFN-β (Miltenyi; 20 ng/ml), IFN-γ or IL-21 (Peprotech; 20 ng/ml).

T helper cell subset differentiation

CD4+ T cells were enriched from PBMCs by negative selection using magnetic beads (Miltenyi) and naïve CD45RA+CCR7+CD4+ T cells were then isolated by cell sorting using a BD FACSAria™ cytometer. Naïve CD4+ T cells were seeded at a concentration of 5 × 105 cells per well in a 96 well plate in complete medium and stimulated with anti-CD2/CD3/CD28 beads (Miltenyi) alone (TH0 condition) or in the presence of human recombinant cytokines: For TH1 conditions IL-12 (20ng/mL) (Biolegend); for TH17 conditions IL-6 (20ng/mL), IL-23 (10ng/mL) (Biolegend) and TGF-β1 (5 ng/mL) (R&D Systems); for TFH conditions IL-12 (2ng/mL), IL-23 (10 ng/mL) and TGF-β1 (5ng/mL)35.

Statistical Analysis

Comparisons between the patient and healthy controls were analyzed using the unpaired Student's t-test, and one-way or two-way ANOVA with post-test analysis. Two-sided p-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Refractory autoimmune cytopenias associated with a novel GOF STAT1 mutation

A 10-year-old girl with a longstanding history of Evans syndrome manifesting in autoimmune hemolytic anemia (AIHA) and immune thrombocytopenia (ITP) presented to our institution with an acute exacerbation of her disease (in the following referred to as “the” patient (pt) or patient 1 (pt 1)). She required daily packed red blood cell (PRBC) transfusions to keep her hemoglobin above 6g/dL and suffered from systemic bleeding symptoms refractory to transfusion of platelets. At presentation, the patient had already been treated with a prolonged course of steroids and multiple doses of intravenous immunoglobulins. While these therapies had failed to induce remission, withdrawal of steroids spurred the rate of hemolysis further, necessitating continued glucocorticoid therapy.

The patient had a history of chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis involving her nails, oral mucosa and vaginal tract. She also suffered from chronic diarrhea and severe chronic lung disease with respiratory insufficiency requiring supplemental oxygen. She was a poor responder to vaccines and had been treated with immunoglobulin replacement over extended periods of her life. The parents were non-consanguineous, and there was no family history of autoimmunity, immunodeficiency or other blood dyscrasias. HLA-typing revealed that the patient's only sibling was not a match.

A comprehensive diagnostic evaluation revealed positive anti-platelet IgM antibodies as well as a complement fixing, high affinity, high thermal amplitude cold agglutinin. Consequently, the patient received a course of the anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody rituximab followed by the anti-complement C5 antibody eculizumab without clinical improvement. Over the course of the following 6 weeks, the patient's reticulocyte count and absolute neutrophil count (ANC) started to fall while ferritin and LDH were rising. Serial bone marrow biopsies demonstrated a steady decline in bone marrow cellularity from greater than 70% prior to admission to less than 10% 11 weeks later, leading to the diagnosis of acquired aplastic anemia. A bone marrow aspirate also revealed occasional CD163+ hemophagocytic histiocytes for which treatment with the IL-1 receptor antagonist anakinra for presumed macrophage activation syndrome was added to the baseline steroid therapy. A diagnostic workup for genetic causes of bone marrow failure was non-revealing. Accordingly, the patient received standard immunosuppressive therapy for idiopathic aplastic anemia without available matched sibling donor consisting of 4 doses of equine anti-thymocyte globulin (ATG) and cyclosporine A. While the initial post-treatment course was complicated by intraventricular hemorrhage and acute respiratory decompensation, over the following 8-week period the patient's clinical course stabilized. The ANC and reticulocyte count began to rise, consistent with bone marrow recovery in response to treatment with ATG and cyclosporine A. Hemolysis, however, started to flare and hemoglobin rapidly declined again as soon as steroids were weaned, indicating that ATG and cyclosporine A successfully treated the patient's aplastic anemia but failed to bring the autoimmune cytopenias into complete remission (Fig 1 and Fig E1 in the Online Repository). Together with the development of acute steroid induced diabetes, the need for an alternate therapy to control the persisting autoimmune cytopenias became critical.

Figure 1. Hemoglobin and platelet count in response to pharmacotherapy.

Graph depicts serum hemoglobin concentration in g/dL (gray curve) and platelet count in 103 cells/μL (black curve) in response to changes in steroid dose, as well as pharmacotherapy with anti-thymocyte globulin (ATG), the IL-1 receptor antagonist anakinra, cyclosporine A and ruxolitinib. Timing of packed red blood cell (PRBC) transfusions is indicated in dark gray. The prednisone dose is expressed in mg/kg body weight.

Unbiased genetic testing for 200 known/selected inborn errors of immunity identified a monoallelic de novo missense mutation in the coding region of STAT1 that resulted in an amino acid substitution in the linker domain of the protein and was predicted to be deleterious by SIFT and Polyphen2 (c.1633G>A; p.E545K) (Fig 2A, B). Structure modeling revealed that the E545 residue is far away from the previously proposed STAT1 dimerization interface, but close to the SH2 domain that binds the activating IFN-γ receptor peptide, suggesting that this mutation may affect STAT dimer binding to cytokine receptors or kinases.32 This mutation did not affect the expression of total STAT1 protein in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells or in B cells at baseline (Fig 2C and data not shown). However, upon stimulation of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) with IFN-β (20 ng/mL) or IFN-γ (20 ng/mL) the patient's CD4+ T cells demonstrated a significant increase in STAT1 phosphorylation compared to control cells (Fig 2D). Unlike other reported GOF STAT1 mutations, the E545K mutation did not impact the dephosphorylation kinetics upon cytokine deprivation, which led to normalization of phospho-STAT1 expression down to baseline in patient and control cells over the same amount of time (Fig 2E). Similar results were found upon stimulation and withdrawal of patient CD8+ T cells with the respective IFN (data not shown). These results suggest that the E545K mutation is an atypical GOF STAT1 mutation leading to hyper-phosphorylation of STAT1 in response to types I and II IFN without interfering with the dephosphorylation process.

Figure 2. STAT1 E545K mutation leads to hyperphosphorylation gain of function.

(A) Sanger sequencing revealed a monoallelic 1633G>A substitution in STAT1. (B) Structural alignment between STAT1 structure and modeled E545K mutant structure (white). WT domains are colored (SH2 in green, dimerization domain in cyan, and IFN-γ peptide in orange) to highlight their position relative to residue 545 (WT structure in yellow and mutant in magenta). (C) Total STAT1 expression in CD4+ T cells by flow cytometry in pt 1 and control. (D) Phospho-STAT1 expression in CD4+ T cells stimulated with IFN-β (20 ng/mL) and IFN-γ (20 ng/mL) in patient and control (top) and dose response curve with increasing interferon concentrations (bottom). (E) Dephosphorylation kinetics of phospho-STAT1 in response to deprivation of IFN-β and IFN-γ in CD4+ T cells represented as absolute MFI (top) and normalized to maximum expression prior to deprivation (bottom). *** p<0.001 by two-way ANOVA.

STAT1E545K mediates exaggerated TH1/TC1 skewing and suppresses TH17 cell differentiation

Examination of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) 6 months post ATG and rituximab therapy revealed that the patient had a higher proportion of IFN-γ-producing and lower proportion of IL-17-producing circulating CD4+ and CD8+ T cells as compared to healthy controls (Fig 3A, B). To gain insight into the link between the STAT1E545K mutation and patient's clinical presentation with autoimmunity, we evaluated the number of follicular helper T cells (TFH), defined as CD4+CXCR5+PD1+ cells35, 36. Patient CD4+ T cells showed an approximately 7-fold increase in the fraction of CXCR5+, PD1+ TFH cells compared to healthy control cells (Fig 3C) suggestive of an increased risk of dysregulated humoral immunity conferred by the STAT1E545K mutation.

Figure 3.

STAT1E545K GOF mutation results in exacerbated TH1/TC1 and TFH responses and impaired TH17/Tc17 immunity. (A) Representative flow cytometric analyses of IL-17 and IFN-γ secretion by peripheral CD4+ and CD8+ T cells from STAT1E545K patient and controls. (B) Dot plots represent frequencies of IFN-γ and IL-17 producing CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in each group. N=8-9 individual controls and the STAT1E545K patient at three different time points. (C) CXCR5 and PD1 expression in CD4+ T cells from patient 1 (STAT1E545K) and patient 2 (STAT1T385M) compared to healthy controls. (D) CXCR3 and CCR6 expression in CD4+CXCR5+PD1+ T cells from patients 1, 2 and healthy controls (gates shown above).

To corroborate the hypothesis that dysregulated T follicular helper cell immunity is a primary feature of amplified STAT1 activity, we selected a second patient (pt 2) with different STAT1T385M mutation, known to confer gain of function activity based on previous reports in the literature.13, 26, 27 As expected, CD4+ T cells from pt 2 displayed exaggerated STAT1-phosphorylation in response to in vitro stimulation with types I and II IFN which could also be mitigated by in vitro treatment with ruxolitinib (Fig E2 in the Online Repository). Importantly, pt 2 suffered from chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis and opportunistic infectious without any clinical evidence of autoimmunity and displayed an increase in the fraction of circulating CXCR5+, PD1+ TFH cells (Fig 3 C). The TFH cells of both pt 1 and pt 2 exhibited high expression of the pro-TH1 chemokine receptor CXCR3 and decreased expression of the pro-TH17 chemokine receptor CCR6, in agreement with previous studies (Figure 3D).37, 38

The Janus kinase 1/2 inhibitor ruxolitinib suppresses dysregulated STAT1E545K phosphorylation induced by IFNs

The JAK inhibitors ruxolitinib and tofacitinib, which primarily target JAK1/2 and JAK3 respectively, have been used to target dysregulated JAK/STAT activity in different clinical conditions10, 24. To investigate, which of these two JAK inhibitors is most specific in normalizing STAT1E545K activity without interfering with STAT3 signaling relevant to TH17 differentiation, we tested the effects of ruxolitinib and tofacitinib on STAT1 and STAT3 activation in response to IFN-β and IFN-γ or IL-21 stimulation respectively. Both drugs suppressed STAT1 and STAT3 phosphorylation in pt 1 and control CD4+ T cells in a concentration dependent manner. Ruxolitinib was more selective in suppressing STAT1 phosphorylation in response to IFN-β stimulation compared to tofacitinib, reflective of a lesser half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) necessary to block JAK1/2 activation (Fig 4A).39 In contrast, ruxolitinib was more sparing towards STAT3 phosphorylation in response to IL-21 stimulation, reflective of its higher IC50 towards JAK3 compared to tofacitinib (Fig 4B). Optimal effects were achieved with ruxolitinib at a concentration of 10 nM, which decreased the STAT1 phosphorylation in patient CD4+ T cells from over 400% prior to treatment to approximately 150 % of the STAT1 activity in vehicle treated control CD4+ T cells (Fig 4C) while maintaining over 80% of the baseline STAT3 activity (Fig 4D). The suppressive effect of tofacitinib on STAT1 and STAT3 phosphorylation in control and patient CD4+ T cells in response to IFN-β and IL-21 stimulation was dose-dependent but non-selective with equal IC50 for STAT1 and STAT3, making it less suitable to treat isolated STAT1 hyper-reactivity (Fig 4 A-D).

Figure 4. Different Janus kinase inhibitors variably inhibit STAT1 and STAT3 phosphorylation in vitro.

(A) Phospho-STAT1 expression upon IFN-β stimulation in CD4+ T cells from control and STAT1E545K patient treated in vitro with 10nM and 100nM concentrations of ruxolitinib (red curve) and tofacitinib (blue curve) or vehicle (DMSO, black curve). Plain grays correspond to unstimulated cells. (B) Phospho-STAT1 mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) expressed as percent of maximum vehicle-treated control CD4+ T cells shown in (A). (C) Phospho-STAT3 expression upon IL-21 stimulation in CD4+ T cells from control and STAT1E545K patient treated in vitro with 10nM and 100nM concentrations of ruxolitinib (red curve) and tofacitinib (blue curve) or vehicle. Plain grays correspond to unstimulated cells. (D) Phospho-STAT3 mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) expressed as percent of maximum vehicle-treated control CD4+ T cells shown in (C). ** p<0.001 and *** p<0.0001 two-way ANOVA with post test analysis.

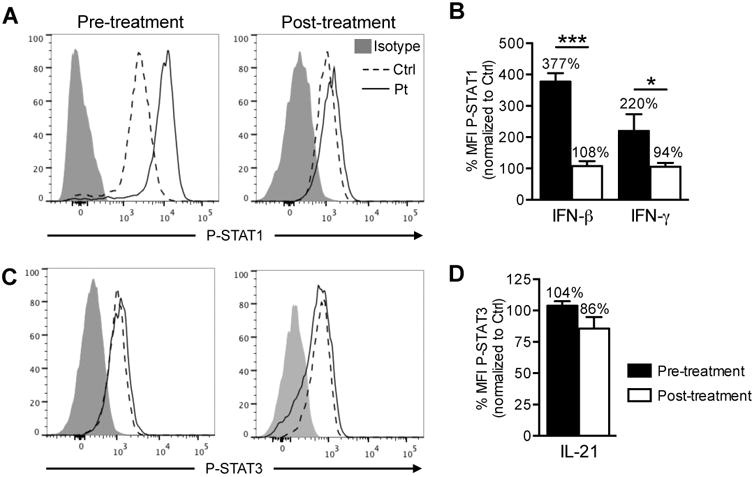

Janus kinase inhibitor treatment controls STAT1 phosphorylation

Based on these in vitro data we started treating the STAT1E545K patient (pt 1) with ruxolitinib. We adjusted the ruxolitinib treatment dose in the patient so that STAT1 phosphorylation in response to stimulation with IFN-β and IFN-γ in patient CD4+ T cells decreased to approximately 100% relative to control CD4+ T cells (Fig 5A, B). At this dose, equivalent to 10 mg/m2 BSA, patient STAT3 phosphorylation in CD4+ T cells in response to IL-21 stimulation was maintained at >80% relative to control CD4+ T cells, matching our in vitro findings (Fig 5C, D).

Figure 5. Janus kinase inhibitor treatment controls STAT1 phosphorylation.

(A) Expression of phospho-STAT1 in CD4+ T cells of STAT1E545K patient and control pre-and post in vivo therapy with ruxolitinib after IFN-β stimulation. (B) Histogram represents phospho-STAT1 MFI normalized to expression in control CD4+ T cells after IFN-β or IFN-γ stimulation pre- and post in vivo therapy with ruxolitinib. (C) Expression of phospho-STAT3 in CD4+ T cells of STAT1E545K patient and control pre- and post in vivo therapy with ruxolitinib after IL-21 stimulation. (D) Histogram represents phospho-STAT3 MFI normalized to expression in control CD4+ T cells after IL-21 stimulation pre-and post in vivo therapy with ruxolitinib.

Ruxolitinib treatment normalizes amplified TH1 and improves impaired TH17 responses

After 3-4 months of ruxolitinb therapy at target dose, the IFN-γ production in circulating patient CD4+ T cells had decreased significantly, while IL-17 production in circulating CD4+ T cells initially remained low despite clinical improvement of mucocutaneous candidiasis and diarrhea. After over one year of therapy with ruxolitinib and following discontinuation of all other immunosuppressive medications IFN-γ production in CD4+ T cells from the STAT1E545K patient remained suppressed to the level of normal control cells while IL-17 production increased along with consolidation of the clinical picture. (Fig 6A, B). To assess if ruxolitinib also has an effect on the aberrant priming of undifferentiated cells, we investigated the capacity of naïve pt 1 CD4+ T cells to polarize into IFN-γ or IL-17 producing TH1 or TH17 cells respectively, by in vitro differentiation under TH0 (anti-CD2/CD3/28), TH1 (anti-CD2/CD3/28, IL-12) and TH17 (anti-CD2/CD3/28, IL-6, IL-23, TGF-β1) conditions (Fig 6 C, D). Our results revealed that the patient's naïve CD4+ T cells were biased to adopt TH1 fate with marked skewing towards IFN-γ production under all 3 conditions as compared to control T cells. In contrast, IL-17 production was suppressed especially under TH17 polarizing condition. Importantly, the priming of the STAT1E545K mutation towards a TH1/TC1 phenotype and antagonizing TH17 differentiation was almost entirely reversible by long term treatment (>12 months) of the patient with ruxolitinib. No further drug was added to the in vitro culture conditions.

Figure 6. Ruxolitinib treatment normalizes amplified TH1 and strengthens impaired TH17 responses.

(A) Expression of IFN-γ and IL-17 in CD4+ T cells of patient pre- and post in vivo therapy with ruxolitinib at target dose after 3-4 months and >12 months, respectively. (B) Histograms represent frequencies of IFN-γ and IL-17 producing CD4+ T cells shown in panel (A). ** p<0.01 and *** p<0.001 by unpaired two-tailed Student's t-test. (C) Expression of IFN-γ and IL-17 in control and STAT1E545K patient naïve CD4+ T cells cultured under TH0, TH1 and TH17 conditions before and after initiation of ruxolitinib treatment. (D) Histograms represent frequency of IFN-γ and IL-17 producing CD4+ T cells under TH0, TH1 and TH17 conditions respectively. The pre-treatment samples were obtained at least 6 months post ATG and rituximab treatment. The post-treatment samples were obtained after at least 12 months of ruxolitinib treatment at target dose. One representative experiment out of 2 is shown. * p<0.05, ** p<0.01 and *** p<0.001 by unpaired two-tailed Student's t-test (B) or two-way ANOVA (D) with post-test analysis.

Ruxolitinib maintenance therapy reverses dysregulated TFH cell expansion associated with STAT1E545K

To investigate if ruxolitinib is also effective in controlling the augmented TFH response and possible TFH priming caused by STAT1E545K, we assessed the in vitro differentiation capacity of naïve pt 1 CD4+ T cells into TFH cells with TGF-β1, IL-12 and IL-23 prior to treatment with ruxolitinib and at multiple time points (3 months, 12 months thereafter).40 After only 3 months of ruxolitinib at target dose, the number of circulating TFH cells in the STAT1E545K patient normalized down to the level of the control (Fig 7A, B) and remained stable over the course of 12 months thereafter (data not shown). To generate evidence that the enlarged TFH compartment is a primary phenotype of the STAT1E545K mutation and not a consequence of the longstanding history of autoimmune disease in our patient, we performed in vitro polarization studies showing that naïve pt 1 CD4+ T cells had a profoundly exaggerated response to stimulation with TGF-β1, IL-12 and IL-23 compared to control, which led to the development of an expanded population of CXCR5+ICOS+ TFH-like cells with higher ICOS expression levels. Ruxolitinib inhibited in vitro TFH development in response to TGF-β1, IL-12 and IL-23 leading to a number of CXCR5+ICOS+ TFH-like cells in the STAT1E545K mutation that was comparable to the control prior to treatment (Fig 7 C-E).

Figure 7. Ruxolitinib treatment corrects exacerbated TFH response in patient with STAT1E545K mutation.

(A) CXCR5 and PD1 expression in CD4+ T cells in STAT1E545K patient pre- and post-treatment with ruxolitinib at target dose for 3 months compared to control. (B) Histograms represent frequencies of TFH cells in STAT1E545K patient pre-and post-treatment compared to control. (C) CXCR5 and ICOS expression in in vitro-differentiated TFH-like cells from patient and control stimulated with TGF-β1, IL-12 and IL-23 in the presence or absence of ruxolitinib. (D) Histograms represent frequencies of in vitro-differentiated TFH cells with and without ruxolitinib in patient and control. (E) ICOS MFI in in vitro-differentiated TFH cells with and without ruxolitinib in patient and control. * p<0.05, ** p<0.01 and *** p<0.001 by one-way (B, D, E) and two-way (D, E) ANOVA with post-test analysis.

Discussion

In this report we describe that a patient with a novel STAT1E545K GOF mutation in the linker domain, which is associated with increased STAT1 phosphorylation, immune dysregulation, and intractable life-threatening autoimmune cytopenias, favorably responded to therapy with ruxolitinib. Long-term therapy addressed all immune-phenotypic features of the disease, including cytokine-induced STAT1 hyper-phosphorylation, amplified TH1 and TFH differentiation, impaired TH17 immunity and the respective aberrant priming of naïve cells. Ruxolitinib controlled the autoimmune cytopenias, cured mucocutaneous candidiasis and diarrhea, led to a gradual amelioration of pulmonary function (post-ruxolitinib FVC 90%, FEV1 80% compared to FVC 75%, FEV1 66% prior to treatment) and allowed us to wean the patient off all other immunosuppressive therapy. Initial concerns ruxolitinib could cause JAK2-mediated dose-limiting myelosuppression and anemia proved unsubstantiated. Thus, JAK inhibitor therapy represents a rational and effective therapy in this disease. As with all immunomodulatory and immunosuppressive medications, careful clinical surveillance for side effects including serious infections and malignancy is warranted.

Like other GOF STAT1 mutations, the STAT1E545K mutation augmented STAT1 phosphorylation in response to cytokine signaling. However, unlike other common GOF STAT1 mutations, it potentiated STAT1 phosphorylation without affecting dephosphorylation following withdrawal of the activating cytokine.14 Also, it did not perturb the basal levels of phospho-STAT1 absent cytokine stimulation, suggesting that it promoted increased recruitment of STAT1 at the respective cytokine receptor. Of note, STAT3 phosphorylation was normal.

The STAT1E545K mutation augmented the in vitro polarization of naïve CD4+ T cells into TH1 and TFH cell subsets while rendering them resistant to TH17 polarization. Similar skewing of helper T cell subsets was also observed in vivo, with the patient showing increased TH1 and TFH but decreased TH17 cells in circulation. Suppressed TH17 differentiation was noted despite normal STAT3 phosphorylation. Our findings are consistent with recent studies demonstrating that STAT1 GOF mutations act distally to suppress STAT3 activation of components of the TH17 transcriptional program, including RORC, without affecting cytokine-mediated STAT3 phosphorylation.41 Surprisingly, the STAT1E545K mutation was associated with a markedly expanded pool of circulating TFH cells. Similar observations were made in a patient (pt 2) with a different STAT1 GOF mutation affecting the DNA-binding domain who was clinically free from any signs of autoimmunity. These findings suggest that a dysregulated TFH cell response is a primary feature of increased STAT1 activity independent of and not secondary to clinical autoimmunity. The molecular mechanisms leading to this enlarged TFH cell compartment are not clear. TFH cell expansion has been associated with humoral autoimmunity, and several monogenic immune dysregulatory diseases with humoral autoimmunity are associated with an expanded TFH cell pool, including CTLA4 and LRBA deficiency 36, 42.

By decreasing STAT1 hyper-phosphorylation, JAK inhibitors combat the sequelae of unopposed interferon release, normalize TH1 and TFH responses and treat autoimmunity. In our studies long term JAK inhibitor treatment also promoted TH17 differentiation of naïve CD4+ T cells in vitro and rescued IL-17 production in vivo, which was clinically reflected by a significant improvement in mucosal immunity under ruxolitinib therapy. This is in line with the observations of Higgins et al. and Mössner et al. who report improvement of oral candidiasis in response to ruxolitinib and relapse as the drug was withdrawn.10, 41 Our concerns that JAK-inhibition could compromise mucosal immunity further by decreasing STAT3 activity proved unsubstantiated, as ruxolitinib only had a minor impact on STAT3 signaling.

The observation that ruxolitinib therapy reversed the exaggerated TFH phenotype and priming caused by STAT1E545K in its entirety is concordant with its ability to control the autoimmune manifestations in our patient over a time period of over eighteen months. These observations suggest a role for JAK inhibitors as a maintenance treatment to prevent the development of further autoimmune disease, for which STAT1 GOF-patients are at extremely high risk over their lifetime. The availability of a targeted small molecule therapy is particularly relevant in severely affected patients, in which a donor for allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation is not available. Even with a suitable donor, the extent of auto- and allosensitization in patients with a longstanding history of autoimmunity together with their inherent underlying comorbidities often call the indication to proceed with an allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant into question.

The findings described above have implications for a broad patient population. As STAT1 GOF mutations can present with a wide range of clinical phenotypes, heightened clinical vigilance should prompt the physician to consider this diagnosis in any patient with autoimmune disease associated with mucocutaneous candidiasis or other opportunistic infections. Finally, this case illustrates how profoundly the knowledge about the molecular underpinnings of autoimmune conditions can impact therapy and outcome.

Supplementary Material

Figure E1. Hemoglobin and platelet count in response to pharmacotherapy. Graph depicts absolute reticulocyte count in 103 cells/μL (gray curve) and absolute neutrophil count in cells/μL (black curve) in response to changes in steroid dose, as well as therapy with anti-thymocyte globulin (ATG), the IL-1 receptor antagonist anakinra, cyclosporine A and ruxolitinib. Timing of packed red blood cell (PRBC) transfusions is indicated in dark gray. The prednisone dose is expressed in mg/kg body weight.

Figure E2. STAT1ET385M mutation in patient 2 leads to hyperphosphorylation gain of function. (A) Phospho-STAT1 expression in CD4+ T cells stimulated with IFN-β and IFN-γ in the STAT1T385M patient (pt 2) and control. (B) Dose response curve of STAT1 phosphorylation induced with IFN-β and IFN-γ in CD4+ T cells of pt 2 and control. (C) Dephosphorylation kinetics of phospho-STAT1 in response to deprivation of IFN-β and IFN-γ in CD4+ T cells represented as absolute MFI (top) and normalized to maximum expression prior to deprivation (bottom). (D) Phospho-STAT1 expression upon IFN-β stimulation in CD4+ T cells of pt 2 and control treated in vitro with ruxolitinib (red curve) and tofacitinib (blue curve) or vehicle (DMSO, black curve). Plain grays correspond to unstimulated cells. (E) Phospho-STAT1 and phospho-STAT3 mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) expressed as percent of maximum vehicle-treated control CD4+ T cells shown in (D) in response to increasing concentrations of ruxolitinib (red curve) and tofacitinib (blue curve).

Key messages.

A STAT1E545K gain of function mutation mediated TH1/TC1 skewing, TH17 cell suppression and an exaggerated TFH response.

The Janus-Kinase inhibitor ruxolitinib mitigated STAT1-hyperphosphorylation, normalized TH1 and TFH differentiation and improved TH17 development both in vitro and in vivo.

Acknowledgments

Funding sources: This work was supported by the US National Institutes of Health grants 2R01AI085090 and 1R56AI115699 to T.A.C.

Abbreviations

- AIHA

autoimmune hemolytic anemia

- ANC

absolute neutrophil count

- BSA

Body surface area

- CD

cluster of differentiation

- Ctrl

Healthy Control Subject

- eATG

equine anti-thymocyte globuline

- GOF

gain of function

- Hb

hemoglobin

- HLA

Human leukocyte antigen

- IL

Interleukin

- IFN

Interferon

- ITP

immune thrombocytopenia

- IvIg

intravenous immunoglobulins

- JAK

Janus Kinase

- LDH

Lactate Dehydrogenase

- LOF

loss of function

- MFI

Mean Fluorescence Intensity

- PBMC

Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cell

- PRBC

packed red blood cells

- Pt

Patient

- STAT

signal transducer and activator of transcription

- TC1

T cytotoxic cell type 1

- TC17

T cytotoxic cell type 17

- TFH

T follicular helper cell

- TH1

T helper cell type 1

- TH17

T helper cell type 17

Footnotes

Contribution: K.G.W, L.-M.C. and T.A.C. designed the research, performed experiments, analyzed data, designed figures, and wrote the manuscript; F.A. performed experiments and analyzed data; Q.Q. and H. W. performed the structural analysis; C.M. advised with the statistical analysis and reviewed the manuscript; L.D.N., S.D.R, T.A.F. and T.R.T. participated in establishing the molecular diagnosis, reviewed the manuscript and provided thoughtful discussions; I.C.H. and L.R.F. contributed patient samples and reviewed the manuscript. A.P. and K.G.W. clinically managed the patient.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Boisson-Dupuis S, Kong XF, Okada S, Cypowyj S, Puel A, Abel L, et al. Inborn errors of human STAT1: allelic heterogeneity governs the diversity of immunological and infectious phenotypes. Curr Opin Immunol. 2012;24:364–78. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2012.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Subramaniam PS, Torres BA, Johnson HM. So many ligands, so few transcription factors: a new paradigm for signaling through the STAT transcription factors. Cytokine. 2001;15:175–87. doi: 10.1006/cyto.2001.0905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O'Shea JJ, Holland SM, Staudt LM. JAKs and STATs in immunity, immunodeficiency, and cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:161–70. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1202117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.vdV FL. STAT1 Mutations in Autosomal Dominant Chronic Mucocutaneous Candidiasis. N Engl J Med. 2011:54–61. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1100102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hori T, Ohnishi H, Teramoto T, Tsubouchi K, Naiki T, Hirose Y, et al. Autosomal-dominant chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis with STAT1-mutation can be complicated with chronic active hepatitis and hypothyroidism. J Clin Immunol. 2012;32:1213–20. doi: 10.1007/s10875-012-9744-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu L, Okada S, Kong XF, Kreins AY, Cypowyj S, Abhyankar A, et al. Gain-of-function human STAT1 mutations impair IL-17 immunity and underlie chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis. J Exp Med. 2011;208:1635–48. doi: 10.1084/jem.20110958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nahum A, Dala lI. Clinical manifestations associated with novel mutations in the coiled-coil domain of STAT1. LymphoSign J. 2014;1:97–103. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roifman C. Monoallelic STAT1 mutations and disease patterns. LymphoSign J. 2014;1:57–9. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sharfe N, Nahum A, Newell A, Dadi H, Ngan B, Pereira SL, et al. Fatal combined immunodeficiency associated with heterozygous mutation in STAT1. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133:807–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Higgins E, Al Shehri T, McAleer MA, Conlon N, Feighery C, Lilic D, et al. Use of ruxolitinib to successfully treat chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis caused by gain-of-function signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 (STAT1) mutation. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;135:551–3 e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.12.1867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yamazaki Y, Yamada M, Kawai T, Morio T, Onodera M, Ueki M, et al. Two novel gain-of-function mutations of STAT1 responsible for chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis disease: impaired production of IL-17A and IL-22, and the presence of anti-IL-17F autoantibody. J Immunol. 2014;193:4880–7. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1401467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sampaio EP, Hsu AP, Pechacek J, Bax HI, Dias DL, Paulson ML, et al. Signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 (STAT1) gain-of-function mutations and disseminated coccidioidomycosis and histoplasmosis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;131:1624–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.01.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frans G, Moens L, Schaballie H, Van Eyck L, Borgers H, Wuyts M, et al. Gain-of-function mutations in signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 (STAT1): chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis accompanied by enamel defects and delayed dental shedding. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134:1209–13 e6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.05.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mizoguchi Y, Tsumura M, Okada S, Hirata O, Minegishi S, Imai K, et al. Simple diagnosis of STAT1 gain-of-function alleles in patients with chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis. J Leukoc Biol. 2014;95:667–76. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0513250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bohmer FD, Friedrich K. Protein tyrosine phosphatases as wardens of STAT signaling. JAKSTAT. 2014;3:e28087. doi: 10.4161/jkst.28087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kumar N, Hanks ME, Chandrasekaran P, Davis BC, Hsu AP, Van Wagoner NJ, et al. Gain-of-function signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 (STAT1) mutation-related primary immunodeficiency is associated with disseminated mucormycosis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134:236–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.02.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tóth B, Méhes L, Taskó S, Szalai Z, Tulassay Z, Cypowyj S, et al. Herpes in STAT1 gain-of-function mutation. The Lancet. 2012;379:2500. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60365-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Puel A, Cypowyj S, Marodi L, Abel L, Picard C, Casanova JL. Inborn errors of human IL-17 immunity underlie chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;12:616–22. doi: 10.1097/ACI.0b013e328358cc0b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Romberg N, Morbach H, Lawrence MG, Kim S, Kang I, Holland SM, et al. Gain-of-function STAT1 mutations are associated with PD-L1 overexpression and a defect in B-cell survival. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;131:1691–3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.O'Shea JJ, Schwartz DM, Villarino AV, Gadina M, McInnes IB, Laurence A. The JAK-STAT Pathway: Impact on Human Disease and Therapeutic Intervention. Annu Rev Med. 2015;66:311–28. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-051113-024537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aldave JC, Cachay E, Nunez L, Chunga A, Murillo S, Cypowyj S, et al. A 1-year-old girl with a gain-of-function STAT1 mutation treated with hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. J Clin Immunol. 2013;33:1273–5. doi: 10.1007/s10875-013-9947-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wildbaum G, Shahar E, Katz R, Karin N, Etzioni A, Pollack S. Continuous G-CSF therapy for isolated chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis: complete clinical remission with restoration of IL-17 secretion. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;132:761–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Faitelson YBA, Shroff M, Grunebaum Y, Roifman CM, Naqvi M. A mutation in the STAT1 DNA-binding domain associated with hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. LymphoSign J. 2014;1:87–95. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu Y, Jesus AA, Marrero B, Yang D, Ramsey SE, Montealegre Sanchez GA, et al. Activated STING in a vascular and pulmonary syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:507–18. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1312625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mössner R, Diering N, Bader O, Forkel S, Overbeck T, Gross U, et al. Ruxolitinib Induces Interleukin 17 and Ameliorates Chronic Mucocutaneous Candidiasis Caused by STAT1 Gain-of- Function Mutation. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;62:951–3. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Takezaki S, Yamada M, Kato M, Park MJ, Maruyama K, Yamazaki Y, et al. Chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis caused by a gain-of-function mutation in the STAT1 DNA-binding domain. J Immunol. 2012;189:1521–6. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1200926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Soltész B, Tóth B, Shabashova B, Bondarenko A, Okada S, Cypowyj S, et al. New and recurrent gain-of-function STAT1 mutations in patients with chronic mucocutaneous candidiasi. J Med Genet. 2013;50:567–78. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2013-101570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ng PC, Henikoff S. Accounting for human polymorphisms predicted to affect protein function. Genome Res. 2002;12:436–46. doi: 10.1101/gr.212802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Adzhubei IA, Schmidt S, Peshkin L, Ramensky VE, Gerasimova A, Bork P, et al. A method and server for predicting damaging missense mutations. Nat Methods. 2010;7:248–9. doi: 10.1038/nmeth0410-248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60:2126–32. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen X, Vinkemeier U, Zhao Y, Jeruzalmi D, Darnell JE, Jr, Kuriyan J. Crystal structure of a tyrosine phosphorylated STAT-1 dimer bound to DNA. Cell. 1998;93:827–39. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81443-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mao X, Ren Z, Parker GN, Sondermann H, Pastorello MA, Wang W, et al. Structural bases of unphosphorylated STAT1 association and receptor binding. Mol Cell. 2005;17:761–71. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Biasini M, Bienert S, Waterhouse A, Arnold K, Studer G, Schmidt T, et al. SWISS-MODEL: modelling protein tertiary and quaternary structure using evolutionary information. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:W252–8. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Delano WL. The PyMol Molecular Graphics System. 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schmitt N, Liu Y, Bentebibel SE, Munagala I, Bourdery L, Venuprasad K, et al. The cytokine TGF-beta co-opts signaling via STAT3-STAT4 to promote the differentiation of human TFH cells. Nat Immunol. 2014;15:856–65. doi: 10.1038/ni.2947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Charbonnier LM, Janssen E, Chou J, Ohsumi TK, Keles S, Hsu JT, et al. Regulatory T-cell deficiency and immune dysregulation, polyendocrinopathy, enteropathy, X-linked-like disorder caused by loss-of-function mutations in LRBA. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;135:217–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ma CS, Wong N, Rao G, Avery DT, Torpy J, Hambridge T, et al. Monogenic mutations differentially affect the quantity and quality of T follicular helper cells in patients with human primary immunodeficiencies. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;136:993–1006 e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.05.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ma CS, Wong N, Rao G, Nguyen A, Avery DT, Payne K, et al. Unique and shared signaling pathways cooperate to regulate the differentiation of human CD4+ T cells into distinct effector subsets. J Exp Med. 2016 doi: 10.1084/jem.20151467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Quintas-Cardama A, Kantarjian H, Cortes J, Verstovsek S. Janus kinase inhibitors for the treatment of myeloproliferative neoplasias and beyond. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2011;10:127–40. doi: 10.1038/nrd3264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kinnunen T, Chamberlain N, Morbach H, Choi J, Kim S, Craft J, et al. Accumulation of peripheral autoreactive B cells in the absence of functional human regulatory T cells. Blood. 2013;121:1595–603. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-09-457465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zheng J, van de Veerdonk FL, Crossland KL, Smeekens SP, Chan CM, Al Shehri T, et al. Gain-of-function STAT1 mutations impair STAT3 activity in patients with chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis (CMC) Eur J Immunol. 2015;45:2834–46. doi: 10.1002/eji.201445344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kuehn HS, Ouyang W, Lo B, Deenick EK, Niemela JE, Avery DT, et al. Immune dysregulation in human subjects with heterozygous germline mutations in CTLA4. Science. 2014;345:1623–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1255904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure E1. Hemoglobin and platelet count in response to pharmacotherapy. Graph depicts absolute reticulocyte count in 103 cells/μL (gray curve) and absolute neutrophil count in cells/μL (black curve) in response to changes in steroid dose, as well as therapy with anti-thymocyte globulin (ATG), the IL-1 receptor antagonist anakinra, cyclosporine A and ruxolitinib. Timing of packed red blood cell (PRBC) transfusions is indicated in dark gray. The prednisone dose is expressed in mg/kg body weight.

Figure E2. STAT1ET385M mutation in patient 2 leads to hyperphosphorylation gain of function. (A) Phospho-STAT1 expression in CD4+ T cells stimulated with IFN-β and IFN-γ in the STAT1T385M patient (pt 2) and control. (B) Dose response curve of STAT1 phosphorylation induced with IFN-β and IFN-γ in CD4+ T cells of pt 2 and control. (C) Dephosphorylation kinetics of phospho-STAT1 in response to deprivation of IFN-β and IFN-γ in CD4+ T cells represented as absolute MFI (top) and normalized to maximum expression prior to deprivation (bottom). (D) Phospho-STAT1 expression upon IFN-β stimulation in CD4+ T cells of pt 2 and control treated in vitro with ruxolitinib (red curve) and tofacitinib (blue curve) or vehicle (DMSO, black curve). Plain grays correspond to unstimulated cells. (E) Phospho-STAT1 and phospho-STAT3 mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) expressed as percent of maximum vehicle-treated control CD4+ T cells shown in (D) in response to increasing concentrations of ruxolitinib (red curve) and tofacitinib (blue curve).